New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

| |

| Commission overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | April 21, 1962 |

| Jurisdiction | New York City |

| Headquarters | Manhattan Municipal Building One Centre Street, 9th Floor North New York, NY 10007 |

| Commission executive |

|

| Website | www |

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) is the New York City agency charged with administering the city's Landmarks Preservation Law. The LPC is responsible for protecting New York City's architecturally, historically, and culturally significant buildings and sites by granting them landmark or historic district status, and regulating them after designation. It is the largest municipal preservation agency in the nation.[1] As of July 1, 2020[update], the LPC has designated more than 37,800 landmark properties in all five boroughs. Most of these are concentrated in historic districts, although there are over a thousand individual landmarks, as well as numerous interior and scenic landmarks.

Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. first organized a preservation committee in 1961, and the following year, created the LPC. The LPC's power was greatly strengthened after the Landmarks Law was passed in April 1965, one and a half years after the destruction of Pennsylvania Station. The LPC has been involved in several prominent preservation decisions, including that of Grand Central Terminal. By 1990, the LPC was cited by David Dinkins as having preserved New York City's municipal identity and enhanced the market perception of a number of neighborhoods.

The LPC is governed by eleven commissioners. The Landmarks Preservation Law stipulates that a building must be at least thirty years old before the LPC can declare it a landmark.

Role

[edit]

The goal of New York City's landmarks law is to preserve the aesthetically and historically important buildings, structures, and objects that make up the New York City vista. The Landmarks Preservation Commission is responsible for deciding which properties should be subject to landmark status and enacting regulations to protect the aesthetic and historic nature of these properties. The LPC preserves not only architecturally significant buildings, but the overall historical sense of place of neighborhoods that are designated as historic districts.[2] The LPC is responsible for overseeing a range of designated landmarks in all five boroughs ranging from the Fonthill Castle in the North Bronx, built in 1852 for the actor Edwin Forrest, to the 1670s Conference House in Staten Island, where Benjamin Franklin and John Adams attended a conference aimed at ending the Revolutionary War.

The LPC helps preserve the city's landmark properties by regulating changes to their significant features.[3] The role of the LPC has evolved over time, especially with the changing real estate market in New York City.[4]

Potential landmarks are first nominated to the LPC from citizens, property owners, city government staff, or commissioners or other staff of the LPC. Subsequently, the LPC conducts a survey of properties, visiting sites to determine which structures or properties should be researched further. The selected properties will then be discussed at public hearings where support or opposition to a proposed landmark designation are recorded.[5] According to the Landmarks Preservation Law, a building must be at least thirty years old before the LPC can declare it a landmark.[6][7] Approval of a landmark designation requires six commissioners to vote in favor. Approved designations are then sent to the New York City Council, which receives reports from other city agencies including the New York City Planning Commission, and decides whether to confirm, modify, or veto the designation.[8] Before 1990, the New York City Board of Estimate held veto power, rather than the City Council.[9] After the City Council's final approval, a landmark designation may be overturned if an appeal is filed within 90 days.[10]

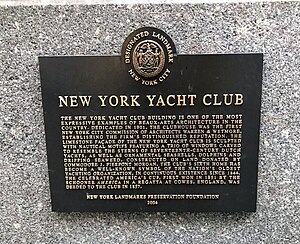

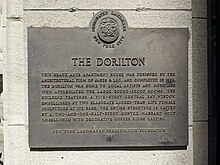

The New York Landmarks Preservation Foundation is a not-for-profit organization, established in 1980 to support the Commission. They sponsor plaques, historic district signs, and street signs.

Staff and departments

[edit]Commissioners

[edit]The Landmarks Preservation Commission consists of 11 commissioners, who are unpaid and serve three-year terms on a part-time basis. By law, the commissioners must include a minimum of six professionals: three architects, a historian, a city planner or landscape architect, and a realtor. In addition, the commissioners must include at least one resident from each of New York City's five boroughs (who may also be a professional). All of the commissioners are unpaid, except for the chairman.[11][5] The commission also employs a full-time, paid workforce of 80, composed of administrators, legal advisors, architects, historians, restoration experts, and researchers. Students sponsored by the federal government, as well as volunteers, also assist the commission.[5]

Departments

[edit]The full-time staff, students, and volunteers are divided into six departments.[12][11][13] The research department performs research of structures and sites that have been deemed potential landmarks. The preservation department reviews and approves permit applications to structures and sites that have been deemed landmarks. The enforcement department reviews reports of alleged violations of the Landmarks Law, which includes alterations to a landmark.[13] In 2016, the preservation commission consolidated its archaeological collection of artifacts and launched a reconstructed archaeology department, known as the NYC Archaeological Repository: The Nan A. Rothschild Research Center.[14] Archaeologists work for the center reviewing the impact of proposed subsurface projects, as well as overseeing any archaeological discoveries.[15] The environmental review department uses data from the research and archaeology departments to collect reports for governmental agencies that require environmental review for their projects.[16] Finally, the Historic Preservation Grant Program distributes grants to owners of landmark properties designated by the LPC or on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).[17]

Types

[edit]As of May 1, 2024[update], there are more than 37,900 landmark properties in New York City, most of which are located in 150 historic districts in all five boroughs. The total number of protected sites includes 1,460 individual landmarks, 121 interior landmarks, and 12 scenic landmarks.[1] Some of these are also National Historic Landmark (NHL) sites, and many are on the NRHP.[1][18] As of 2007[update], the vast majority of interior landmarks are also exterior landmarks or are part of a historic district.[19]

- Individual landmark: The exteriors of objects or structures; the interior is not included unless designated separately. Individual landmarks must be at least 30 years old and contain "a special character or special historical or aesthetic interest or value as part of the development, heritage, or cultural characteristics of the City, state, or nation".[20]

- Interior landmark: The interiors of structures, which fit the individual landmark criteria and are "customarily open or accessible to the public".[20]

- Scenic landmark: Sites owned by the city, which fit the individual landmark criteria and are "parks or other landscape features".[20]

- Historic districts: Regions with buildings that fit the individual landmark criteria and contain "architectural and historical significance". Landmark districts must also be geographically cohesive with a "coherent streetscape" and a "sense of place".[20]

History

[edit]Context

[edit]

The preservation movement in New York City dates to at least 1831, when the New York Evening Post expressed its opposition to the demolition of a 17th-century house on Pearl Street in Lower Manhattan.[21][22] Before the LPC's creation, buildings and structures were preserved mainly through advocacy, either from individuals or from groups.[23] Numerous residences were saved this way, including the Andrew Carnegie Mansion, Percy R. Pyne House, and Oliver D. Filley House, all of which ultimately became individual landmarks after the LPC's formation.[23] Other structures such as the Van Cortlandt House, Morris–Jumel Mansion, Edgar Allan Poe Cottage, and Dyckman House were preserved as historic house museums during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[24] Advocates also led efforts to preserve cultural sites such as Carnegie Hall, which in the late 1950s was slated for replacement with an office tower.[25][26] However, early preservation movements often focused on preserving Colonial-style houses, while paying relatively little attention to other architectural styles or building types.[27]

There was generally little support for the preservation movement until World War II.[22] Structures such as the City Hall Post Office and Courthouse, Madison Square Presbyterian Church (1906), and Madison Square Garden (1890) were demolished if they had fallen out of architectural favor.[28] Others, such as St. John's Chapel, were destroyed in spite of support for preservation.[22][29] By the 1950s, there was growing support for preservation of architecturally significant structures. For example, a 1954 study found approximately two hundred structures that could potentially be preserved.[30][31] At the same time, older structures, especially those constructed before World War I, were being perceived as an impediment to development.[32] The demolition of Pennsylvania Station between 1963 and 1966, in spite of widespread outcry,[33][34] is cited as a catalyst for the architectural preservation movement in the United States, particularly in New York City.[35][36]

Creation

[edit]The Mayor's Committee for the Preservation of Structures of Historic and Esthetic Importance was formed in mid-1961 by mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr.[11][37] This committee had dissolved by early 1962.[38] Wagner formed the Landmarks Preservation Commission on April 21, 1962, with twelve unsalaried members.[11][39][40] Soon afterward, the LPC began designating buildings as landmarks.[40] That July, Wagner issued an executive order that compelled municipal agencies to notify the LPC of any "proposed public improvements".[41]

The early version of the LPC initially held little power over enforcement,[11][42] and failed to avert Pennsylvania Station's demolition.[43] As a result, in April 1964, LPC member Geoffrey Platt drafted a New York City Landmarks Law.[44] Outcry over the proposed destruction of the Brokaw Mansion on Manhattan's Upper East Side, identified by the LPC as a possible landmark, inspired Wagner to send the legislation to the New York City Council in mid-1964.[7][44][45] The law, introduced in the City Council that October, would significantly increase the LPC's powers.[46] The City Council cited concerns that "the City has been and is undergoing the loss and destruction of its architectural heritage at an alarming rate, especially so in the last 8-10 years".[11][47] Several changes to the Landmarks Law were made by the City Council committee that was reviewing the legislation; for example, the committee removed a clause mandating a 400 ft (120 m) protective zone around proposed landmarks.[44][48] The bill passed the City Council on April 7, 1965,[49] and was signed into law by Wagner on April 20.[5][50]

The first eleven commissioners to take office under the Landmarks Law were sworn in during June 1965.[51] Platt was the first chairman, serving until 1968.[52] The LPC's first public hearing occurred in September 1965, and the first twenty landmarks were designated the next month.[53] The Wyckoff House in Brooklyn was the first landmark numerically,[11][54] and was designated simultaneously with structures such as the Astor Library,[55] the Brooklyn Navy Yard's Commandant's House, the Bowling Green U.S. Custom House, and six buildings at Sailors' Snug Harbor.[53] The first landmark district, the Brooklyn Heights Historic District, was designated in November 1965.[11] Within its first year, the LPC designated 37 landmarks in addition to the Brooklyn Heights Historic District. The LPC's earliest landmarks were mainly selected based on their architecture, and were largely either government buildings, institutions, or structures whose preservation was unlikely to be controversial.[8] As a result, several prominent buildings were destroyed in the first several years of the LPC's existence, such as the Singer Building and the New York Tribune Building. Other structures, such as the Villard Houses and Squadron A Armory, were saved only partially.[56]

Changes

[edit]The LPC was headquartered in the Mutual Reserve Building from 1967 to 1980,[57] and in the Old New York Evening Post Building from 1980 to 1987.[58] The original legislation enabled the LPC to designate landmarks for eighteen months after the law became effective, followed by alternating cycles of three-year hiatuses and six-month "designating periods".[5][44][59] In 1973, mayor John Lindsay signed legislation that allowed the LPC to consider landmarks on a rolling basis. The bill also introduced new scenic and interior landmark designations.[44][60][61] The first scenic landmark was Central Park in April 1974,[62] while the first interior landmark was part of the neighboring New York Public Library Main Branch in November 1974.[63]

In its first twenty-five years, the LPC designated 856 individual landmarks, 79 interior landmarks, and 9 scenic landmarks, while declaring 52 neighborhoods with more than 15,000 buildings as historic districts.[64] In 1989, when the LPC and its process was under review following a panel created by mayor Edward Koch in 1985,[65] a decision was made to change the process by which buildings are declared to be landmarks[66] due to some perceived issues with the manner by which the LPC operates[64] as well as the realization that the destruction feared when the LPC was formed was no longer imminent.[65] By 1990, the LPC was cited by David Dinkins as having preserved New York City's municipal identity and enhanced the market perception of a number of neighborhoods. This success is believed to be due, in part, to the general acceptance of the LPC by the city's developers.[2] By 2016, the LPC had designated 1,355 individual landmarks, 117 interior landmarks, 138 historic districts, and 10 scenic landmarks.[11]

Prominent landmarking decisions

[edit]One of the most prominent decisions in which the LPC was involved was the preservation of the Grand Central Terminal with the assistance of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.[67] In 1978, the United States Supreme Court upheld the law in Penn Central Transportation Co., et al. v. New York City, et al., stopping the Penn Central Railroad from altering the structure and placing a large office tower above it.[68] This success is often cited as significant due to the LPC's origins following the destruction of Pennsylvania Station, referred to by some as architectural vandalism.[64]

In 1989, the LPC designated the Ladies' Mile Historic District.[69] The next year marked the first time in the LPC's history that a proposed landmark, the Guggenheim Museum (one of the youngest declared landmarks), received a unanimous vote by the LPC members.[6] The vast majority of the LPC's actions are not unanimously supported by the LPC members or the community; a number of cases including St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church, Bryant Park, and Broadway theatres have been challenged.[70] One of the most controversial properties was 2 Columbus Circle, which remained at the center of a discussion over its future for a number of years.[71]

Cultural landmarks, such as Greenwich Village's Stonewall Inn, are recognized as well not for their architecture, but rather for their location in a designated historic district.[72] In 2015, Stonewall became the first official New York City landmark to be designated specifically based on its LGBT cultural significance.[73]

In a heatedly discussed decision on August 3, 2010, the LPC unanimously declined to grant landmark status to a building on Park Place in Manhattan, and thus did not block the construction of Cordoba House.[74]

Theater District landmarks

[edit]A major dispute arose over the preservation of theaters in the Theater District during the 1980s. The LPC considered protecting close to 50 legitimate theaters as individual city landmarks in 1982, following the destruction of the Helen Hayes and Morosco theaters.[75] An advisory panel under mayor Koch voted to allow the LPC consider theaters not only on their historical significance but also on their architectural merits.[76] In response to objections from some of the major theatrical operators, several dozen scenic and lighting designers offered to work on the LPC for creating guidelines for potential landmarks.[77] Theaters were landmarked in alphabetical order; the first theaters to be designated under the 1982 plan were the Neil Simon, Ambassador, and Virginia (now August Wilson) in August 1985.[78][79][a] The landmark plan was then deferred temporarily until some landmark guidelines were enacted;[80] the guidelines, implemented in December 1985, allowed operators to modify theaters for productions without having to consult the LPC.[81][82]

Landmark designations of theaters increased significantly in 1987,[83] starting with the Palace in mid-1987.[84] Ultimately, 28 additional theaters were designated as landmarks, of which 27 were Broadway theaters. The New York City Board of Estimate ratified these designations in March 1988.[85] Of these, both the interior and exterior of 19 theaters were protected, while only the interiors of seven theaters (including the Lyceum, whose exterior was already protected) and the exteriors of two theaters were approved.[85] Several theater owners argued that the landmark designations impacted them negatively, despite Koch's outreach to theater owners.[86] The Shubert Organization, the Nederlander Organization, and Jujamcyn Theaters collectively sued the LPC in June 1988 to overturn the landmark designations of 22 theaters on the merit that the designations severely limited the extent to which the theaters could be modified.[87] The New York Supreme Court upheld the LPC's designations of these theaters the next year.[88][89] The three theatrical operators challenged the ruling with the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to hear the lawsuit in 1992, thus upholding the designations.[90]

South Street Seaport and "New Market Building"

[edit]An LPC-designated historic district for the South Street Seaport has been active since 1977 and was extended on July 11, 1989.[91] After the Fulton Fish Market relocated to the Bronx in 2005, community members, with leadership from organizer Robert Lavalva,[92] developed the "New Amsterdam Market", a regular gathering with vendors selling regional and "sustainable" foodstuffs outside the old Fish Market buildings. The group's chartered organization planned eventually to attempt to reconstitute the "New Market Building", a 1939 structure with an Art Deco façade[93] and that was owned by the city, into a permanent food market. However, a real estate company, the Howard Hughes Corporation, possessed a lease for large parts of the Seaport area and desired to redevelop it, generating fears among locals that the New Market Building would be altered or destroyed.[93] The corporation has offered to provide a more modest food market (at 10,000 sq ft (930 m2)) into their development plans, but market organizers have not been satisfied as they believe this proposal is not guaranteed or large enough, and would still not ensure the protection of the historic building.[94]

A group of community activists formed the "Save Our Seaport Coalition" to advocate that the New Market Building be incorporated into the historic district set by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, in addition to calling for the protection of public space in the neighborhood and for support for the seaport's museum. This group included the Historic Districts Council, the "Save Our Seaport" community group, the New Amsterdam Market, and the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance.[95] The "Save Our Seaport" group specifically argued that New Market Building was culturally important for its maintenance of the historic fish market for 66 years, and that it offers a "fine example of WPA Moderne municipal architecture (an increasingly rare form throughout the nation)."[96] They had encouraged others to write letters to the LPC to support formal designation or district protection.[96] However, in 2013, the LPC declined to hold a hearing to consider this landmark designation or to expand the district.[93] Community Board 1 supports protecting and repurposing the New Market Building,[93] and the Municipal Art Society argued in a report that "[it] has both architectural and cultural significance as the last functioning site of the important commercial and shipping hub at South Street Seaport."[97]

Little Syria and Washington Street

[edit]After the September 11 attacks in 2001, New York City tour guide Joseph Svehlak and other local historians became concerned that government-encouraged development in Downtown Manhattan would lead to the disappearance of the last physical heritage of the once "low-rise" Lower West Side of Manhattan.[98] Also known as "Little Syria" in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the area between Battery Park and the World Trade Center site, east of West Street and west of Broadway,[99] had been a residential area for the shipping elite of New York in the early 19th century, and turned into a substantial neighborhood of ethnic immigration in the mid-19th century. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, centered on Washington Street, the area became well known as Little Syria, hosting immigrants from today's Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, as well those of many other ethnic groups including Greeks, Armenians, Irish, Slovaks, and Czechs. Due to eminent domain actions associated with the construction of the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel and the World Trade Center,[100] in addition to significant highrise construction in the 1920s and 30s, only a small number of low-rise historic buildings from the earlier eras remain.

In 2003, Svehlak wrote a manifesto arguing for the landmark designation of "a trilogy"[101] of three contiguous buildings on Washington Street, the thoroughfare that was most closely associated with "Little Syria". These consisted of the Downtown Community House – which hosted the Bowling Green Association to serve the neighborhood's immigrants – 109 Washington Street (an 1885 tenement), and the terra-cotta St. George's Syrian Catholic Church. After years of advocacy, in January 2009, the LPC held a hearing about the landmark designation of the Melkite church, which did succeed.[102] However, under Chairman Robert Tierney, the LPC had declined to hold hearings on the Downtown Community House or 109 Washington Street.

Community and preservation groups — including the "Friends of the Lower West Side" and the "Save Washington Street" group led by St. Francis College student Carl "Antoun" Houck[103] — have continued, especially, to advocate for a hearing on the Downtown Community House, arguing that its history demonstrates the multi-ethnic heritage of the neighborhood, and that its Colonial Revival architecture intentionally links the immigrants to the foundations of the country,[104] and that preserving the three buildings together would tell a coherent story of an overlooked, but important ethnic neighborhood.[100] In addition to national Arab-American organizations,[105] Manhattan Community Board 1[106] and City Councilperson Margaret Chin[107] have also advocated for the LPC to hold a hearing on the Downtown Community House. According to the Wall Street Journal, however, the LPC argues that "the buildings lack the necessary architectural and historical significance and that better examples of the settlement house movement and tenements exist in other parts of the city."[100] The activists have said they hope that the LPC under the new mayor will be more receptive to preservation in the neighborhood.[106]

Former landmarks

[edit]Very rarely, a landmark status granted by the LPC has been revoked. Some have been revoked by vote of the New York City Council or before 1990, the New York City Board of Estimate. Others have been demolished, either through neglect or for development, and revoked by the LPC.[108]

| Landmark name | Image | Date designated | Date removed | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 71 Pearl Street | May 17, 1966 | 1968 | Manhattan |

| |

| 135 Bowery | June 29, 2011[110] | September 16, 2011[111] | Manhattan | ||

| Austin, Nichols and Company Warehouse |

|

September 20, 2005 | November 30, 2005[113] | Brooklyn |

|

| Beth Hamedrash Hagodol |

|

February 28, 1967 | Manhattan | ||

| Cathedral of St. John the Divine |

|

June 17, 2003 | October 25, 2003[115] | Manhattan | |

| Coogan (Racquet Court Club) Building | October 3, 1989 | October 8, 1989 | Manhattan | ||

| Dvorak House, 327 East 17th Street | February 1991[118] | June 1991 | Manhattan |

| |

| First Avenue Estate |

|

April 24, 1990[120] | August 16, 1990[9] | Manhattan | |

| Grace Episcopal Memorial Hall |

|

October 26, 2010[122] | January 18, 2011[123] | Queens |

|

| Jamaica Savings Bank, 161-02 Jamaica Avenue |

|

May 5, 1992[124] | 1992 | Queens |

|

| Jamaica Savings Bank, 89-01 Queens Boulevard |

|

June 28, 2005[120] | October 20, 2005[125] | Queens |

|

| Jerome Mansion |

|

November 21, 1965[109] | June 23, 1966[126] | Manhattan |

|

| Lakeman-Cortelyou-Taylor House | December 13, 2016[128] | March 2017 | Staten Island | Landmark 2444 | |

| New Brighton Village Hall | 1965 | December 12, 2006[129] | Staten Island |

| |

| Public School 31 | July 15, 1986 | December 10, 2019[130] | Bronx | ||

| Samuel H. & Mary T. Booth House | November 28, 2017[132] | March 12, 2018[120] | Bronx | Landmark 2488 | |

| Stafford "Osborn" House | November 28, 2017[132] | March 12, 2018[120] | Bronx | Landmark 2479 | |

| Steinway Historic District | November 28, 1974[120] | January 23, 1975[133] | Queens | ||

| Walker Theatre | September 11, 1984 | January 24, 1985[134] | Brooklyn |

See also

[edit]- List of New York City Landmarks

- New York State Register of Historic Places

- New York City Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings (OATH), for hearings conducted on summonses for quality of life violations issued by the LPC

References

[edit]Explanatory notes

- ^ The Neil Simon had been known as the Alvin Theatre; both its interior and exterior were designated. The Ambassador Theatre's interior and exterior were designated, but the exterior status was later overturned. The Virginia/August Wilson was known as the ANTA Theatre; only its exterior was designated.

Citations

- ^ a b c "About LPC". New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Government of New York City. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (April 29, 1990). "Change on the Horizon for Landmarks". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ "Apply for a Permit". Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ Tarquinio, Alex (October 3, 2007). "New Buildings That Embrace the Old". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1120.

- ^ a b Staff (August 19, 1990). "Guggenheim Museum Is Designated a Landmark". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ a b Wood 2008, p. 352.

- ^ a b Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1121.

- ^ a b Purdum, Todd S. (August 16, 1990). "On Estimate Board's Agenda, Last Item Is Its Own Demise". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (November 5, 1987). "5 More Broadway Theaters Classified as Landmarks". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission". NYPAP. April 19, 1965. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "About LPC". Landmarks Preservation Commission. City of New York.

- ^ a b "Departments". New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Bindelglass, Evan (October 6, 2016). "Landmarks Preservation Commission Launches NYC Archaeological Repository". New York YIMBY. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ "Archaeology". New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Environmental Review". New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Preservation Grant Program". New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Landmark Designation". New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Government of New York City. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ Bernstein, Fred A. (September 2007). "In Memoriam". Interior Design. Vol. 78, no. 11. p. 232. ProQuest 234955108.

- ^ a b c d "Landmark Types and Criteria". New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Government of New York City. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ Diamonstein-Spielvogel 2011, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1091.

- ^ a b Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1110.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1092.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, pp. 1112–1113.

- ^ "How to Deflect a Wrecking Ball with a Violin". WNYC. November 6, 2014. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1093.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, pp. 1091–1092.

- ^ "St. John's Chapel Razed". The New York Times. October 6, 1918. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1094.

- ^ "City's Landmarks Subject of Study; Art Societies Find About 200 Pre-world War I Buildings Are Worthy of Preservation". The New York Times. January 24, 1954. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, pp. 1094–11109.

- ^ Rasmussen, Frederick N. (April 21, 2007). "From the Gilded Age, a monument to transit". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1115.

- ^ Muschamp, Herbert (June 20, 1993). "Architecture View; In This Dream Station Future and Past Collide". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ "Laying the Preservation Framework: 1960–1980". Cultural Landscapes (U.S. National Park Service). April 24, 1962. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ "Mayor Appoints 13 To Help Preserve Historic Buildings". The New York Times. July 12, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Whitman Group to Hold Ceremony Honoring Poet". Brooklyn Heights Press. March 8, 1962. p. 8. Retrieved December 17, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "12 Will Tag Sites For Preservation". New York Daily News. April 22, 1962. p. 206. Retrieved December 1, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b Wood 2008, p. 326.

- ^ Bennett, Charles G. (July 1, 1962). "City Asks to Save Landmarks; Names Scholar to New Agency; Van Derpool of Columbia Is Given Post". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Wood 2008, p. 333.

- ^ Ennis, Thomas W. (November 1, 1963). "2 City Landmarks Feared in Danger; Bank and Oldest House May Go Way of Penn Station Penn Station Loss Regretted Street or Landmark?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "New York City Landmarks Law". NYPAP. May 7, 1964. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bill Would Save City Landmarks; Commission Would Pass on Alteration Plans". The New York Times. September 23, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "City Council Gets Landmarks Bill; Preservation of Historical Places in City Is Aim". The New York Times. October 7, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Wood 2008, p. 362.

- ^ Ennis, Thomas W. (March 24, 1965). "Landmarks Bill Goes to Council; Protective Zone Is Cut, but Architecture Rules Stay". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bill on Landmarks Approved by Council". The New York Times. April 7, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Ennis, Thomas W. (April 20, 1965). "Landmarks Bill Signed by Mayor; Wagner Approves It Despite Protests of Realty Men". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Mayor Inducts 11 Members Of Landmark Commission". The New York Times. June 30, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Pace, Eric (July 15, 1985). "Geoffrey Platt Is Dead at 79; Led City Preservation Move". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Fowle, Farnsworth (October 18, 1965). "First Official Landmarks of City Designated; 20 Sites Listed — Each to Get Year's Grace". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Byles, Jeff (March 19, 2006). "Amid the Facades, Furrowed Brows". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Gilbert, Frank B. (November 13, 1991). "Papp Proved that Landmarks Law Works (letter to the editor)". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, pp. 1121–1129.

- ^ Colvin, Jill (December 21, 2011). "Former Home of Macy's and Mutual Reserve Building Become City Landmarks". DNAinfo. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ^ Diamonstein-Spielvogel 2011, p. 283.

- ^ "Landmarks Get City Protection: Right to Save Architectural Heritage Recognized as Government Function". The New York Times. April 11, 1965. p. R1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 1, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Metropolitan Briefs; Lindsay Signs Landmarks Bill". The New York Times. December 18, 1973. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, pp. 1120–1121.

- ^ "Metropolitan Briefs". The New York Times. April 17, 1974. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 25, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ Carroll, Maurice (November 14, 1974). "3 New Sorts of Landmarks Designated in City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c Goldberger, Paul (April 15, 1990). "Architecture View; A Commission that has Itself Become a Landmark". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (December 27, 1987). "Advisory Group to Determine Future of Landmarks Board". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (February 6, 1989). "Panel Urges Deadlines for Votes on Landmarks". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Meistersinger, Toby von (March 7, 2008). "Some Grand Central Terminal Secrets Revealed". Gothamist. Archived from the original on March 10, 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (June 4, 1977). "Office Tower Above Grand Central Barred by State Court of Appeals". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Staff. (May 7, 1989) "Ladies' Mile District Wins Landmark Status", The New York Times

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (November 11, 1988). "Chairman Plans to Leave Panel on Landmarks". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Weiner, Alan S. (October 13, 2003). "The Building That Isn't There". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (June 26, 1999). "Stonewall, Gay Bar That Made History, Is Made a Landmark". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Chalasani, Radhika (June 23, 2015). "Stonewall Inn wins landmark status". CBS News. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved March 10, 2024; Alroy, Tal Trachtman (June 24, 2015). "Stonewall Inn granted landmark status by New York commission". CNN. Archived from the original on December 22, 2023. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ Hernandez, Javier C. (August 3, 2010). "Mosque Near Ground Zero Clears Key Hurdle". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ Goodwin, Michael (April 16, 1982). "Midtown Theaters Surveyed for Landmark Designation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ "THE CITY; City Panel Splits On Theater Plan". The New York Times. October 14, 1983. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Johnston, Laurie; Anderson, Susan Heller (June 23, 1983). "New York Day by Day; Doing Justice to Landmakers And to Theater Interiors". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Schmalz, Jeffrey (August 7, 1985). "Landmarks Panel Listing Broadway Theaters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Polsky, Carol (August 7, 1985). "3 Theaters Named Landmarks". Newsday. p. 32. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Schmalz, Jeffrey (August 14, 1985). "Panel Postpones Landmark Plan for the Theaters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ "Legitimate: Landmarks Panel Issues Guidelines; Owners Not Happy". Variety. Vol. 321, no. 8. December 18, 1985. pp. 89, 94. ProQuest 1438433105.

- ^ Shepard, Joan (December 19, 1985). "Limit on B'way landmarks urged". Daily News. p. 165. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (November 22, 1987). "The Region; The City Casts Its Theaters In Stone". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (June 22, 1987). "Panel Weighs Designating Theater as Landmark". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Purdum, Todd S. (March 12, 1988). "28 Theaters Are Approved as Landmarks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Blau, Eleanor (January 11, 1988). "Koch Is to Hold Talks With Theater Council". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (June 21, 1988). "Owners File Suit to Revoke Theaters' Landmark Status". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Ronald (December 8, 1989). "Theaters' Landmark Status Upheld". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Walsh, Thomas (December 15, 1989). "$200 Million Landmark Lawsuit Dismissed; Designations Are Intact". Back Stage. Vol. 30, no. 50. pp. 1A, 4A. ProQuest 962873540.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (May 27, 1992). "High Court Upholds Naming Of 22 Theaters as Landmarks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Historic Districts Council. "South Street Seaport." Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ Hanania, Joseph. (January 24, 2014) "Duel at the Old Fulton Fish Market" The New York Times Retrieved: August 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Kreuzer, Terese Loeb (September 12, 2013) "City says no to landmarking Seaport building, leaving door open to demolition" Downtown Express. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ Reynolds, Aline. (March 20, 2013) "Food Market For Seaport In Last-Minute Deal Over Pier 17" Tribeca Tribune. Retrieved: August 12, 2014.

- ^ Garfinkel, Molly (ndg) "New Market Building is Place Matters building of the month!". Historic Districts Council. Retrieved: August 12, 2014

- ^ a b "Support Seaport Landmark Preservation". Save Our Seaport. August 5, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ "Fulton Fish Market: New Market Building" (PDF). Municipal Art Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 10, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ Wilensky-Lanford, Brook. (June 3, 2013), "Discovering 'Little Syria' — New York's Long-Lost Arab Neighborhood", Religion Dispatches, retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ Chowdhury, Sudeshna. (June 20, 2013) "Arab Americans Aim at Preserving New York's Little Syria", Inter Press Service. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c Weiss, Jennifer (March 25, 2013), "In Lower Manhattan, Memories of 'Little Syria'", The Wall Street Journal, p. A18, retrieved: August 10, 2014.

- ^ McFarlane, Skye H. (2007). "Tour guide looks to save remnants of 'Little Syria'". Downtown Express. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ Caratzas, Michael D. (July 14, 2009). "(Former) St. George's Syrian Church Designation Report" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 11, 2018.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (January 2, 2012), "An Effort to Save the Remnants of a Dwindling Little Syria", The New York Times, p. A18. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ Eakin, Britain (August 4, 2013) "Activists lobby 9/11 Memorial to remember 'Little Syria'". Al-Arabiya. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ Wallace, Bruce; Werman, Marco (January 19, 2012). "Saving New York's 'Little Syria'". PRI's The World. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Malek, Alia (October 27, 2013), "Rediscovering 'Little Syria' after the storm passed", Aljazeera America, retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ Khan, Taimur (September 21, 2013) "In New York's Little Syria, a fight to preserve the past" The National (Abu Dhabi)) p. A18. Retrieved: August 10, 2014.

- ^ Sternberg, Joachim Beno (April 2011). "New York City's Landmarks Law and the Rescission Process" (PDF). New York University. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c Nevius, James (April 29, 2015). "How Some of NYC's First Landmarked Buildings Became Rubble". Curbed. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Perler, Elie (June 29, 2011). "135 Bowery is Landmarked!". Bowery Boogie. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ "City Council subcommittee turns down Landmarks designation of 135 Bowery". The Real Deal New York. September 15, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Perler, Elie (September 4, 2012). "Demolished 135 Bowery Up For Sale". Bowery Boogie. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Berkey-Gerard, Mark. "City Council Stated Meeting - November 30, 2005". Gotham Gazette. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ "Fire Tears Through Historic Beth Hamedrash Hagodol Synagogue on LES: FDNY". DNAinfo New York. May 14, 2017. Archived from the original on June 2, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Hu, Winnie (October 25, 2003). "No Landmark Status for St. John the Divine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Rosenberg, Zoe (February 21, 2017). "Cathedral of St. John the Divine finally becomes a NYC landmark". Curbed NY. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Dunlap, David (October 8, 1989). "Board Drops 1876 Building As Landmark". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Prial, Frank J. (February 27, 1991). "Dvorak House Declared A Manhattan Landmark". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Lii, Jane H. (September 21, 1997). "Neighborhood Report: Stuyvesant Square; Dvorak, Back Home at Last". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "9 NYC Buildings that Have Lost Their Landmark Status". Untapped New York. March 4, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ "City and Suburban Homes Company, First Avenue Estate" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. April 24, 1990. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ "Grace Episcopal Church Memorial Hall" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 26, 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ "Council rejects designation of Queens church building". CityLand. February 16, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ "(Former) Jamaica Savings Bank" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 12, 2008. p. 9. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ Steele, Lockhart (October 28, 2005). "Elmhurst's Jamaica Savings Bank: Landmark Or Not?". Curbed NY. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Manhattan Club v. Landmarks Comm, 51 Misc. 2d 556 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. June 23, 1966).

- ^ Mendelsohn, Joyce (1998), Touring the Flatiron: Walks in Four Historic Neighborhoods, New York: New York Landmarks Conservancy, p. 26, ISBN 0-964-7061-2-1, OCLC 40227695

- ^ Sommer, Cassy (December 13, 2016). "2 Staten Island buildings named landmarks, as backlog initiative ends". silive. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ "Landmark Site of Former New Brighton Village Hall" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 12, 2006. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Landmarks Rescind Landmarks Designation Status of Former School". CityLand. December 11, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (January 8, 2014). "Bronx Landmark, Under City's Care, Is on Brink of Demolition". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Small, Eddie (November 28, 2017). "Two age-old homes on City Island are now landmarks". The Real Deal New York. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Fowler, Glenn (January 24, 1975). "City Nullifies Designation Of Steinway Historic Area". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ "Brooklyn Cinema Losses Landmark Designation". The New York Times. January 25, 1985. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (March 30, 1988). "Fadeout for Movie Palace in Brooklyn". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

Bibliography

- Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Barbaralee (2011). The Landmarks of New York (5th ed.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-3769-9.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1995). New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial. New York: Monacelli Press. ISBN 1-885254-02-4. OCLC 32159240. OL 1130718M.

- Wood, Anthony C. (2008). Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City's Landmarks. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-95284-2.