Treaty of 1818

| Convention respecting fisheries, boundary, and the restoration of slaves | |

|---|---|

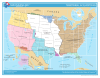

United States territorial border changes | |

| Type | Bilateral treaty |

| Context | Territorial cession |

| Signed | October 20, 1818 |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Effective | January 30, 1819 |

| Signatories | |

| Depositary | Government of the United Kingdom |

| Languages | English |

| Full text | |

The Convention respecting fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves, also known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, is an international treaty signed in 1818 between the United States and the United Kingdom. This treaty resolved standing boundary issues between the two nations. The treaty allowed for joint occupation and settlement of the Oregon Country, known to the British and in Canadian history as the Columbia District of the Hudson's Bay Company, and including the southern portion of its sister district New Caledonia.

The two nations agreed to a boundary line involving the 49th parallel north, in part because a straight-line boundary would be easier to survey than the pre-existing boundaries based on watersheds. The treaty marked both the United Kingdom's last permanent major loss of territory in what is now the Continental United States and the United States' first permanent significant cession of North American territory to a foreign power, the second being the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842. The British ceded all of Rupert's Land south of the 49th parallel and east of the Continental Divide, including all of the Red River Colony south of that latitude, while the United States ceded the northernmost edge of the Missouri Territory north of the 49th parallel.

Provisions

[edit]The treaty name is variously cited as "Convention respecting fisheries, boundary, and the restoration of slaves",[1] "Convention of Commerce (Fisheries, Boundary and the Restoration of Slaves)",[2] and "Convention of Commerce between His Majesty and the United States of America".[3][4]

- Article I secured fishing rights along Newfoundland and Labrador for the US.

- Article II set the boundary between British North America and the United States along "a line drawn from the most northwestern point of the Lake of the Woods, [due south, then] along the 49th parallel of north latitude..." to the "Stony Mountains"[3] (now known as the Rocky Mountains). Britain ceded all territory south of the 49th parallel, including portions of the Red River Colony and Rupert's Land (comprising parts of the present states of Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota). The United States ceded the portion of the Louisiana Purchase lying north of the 49th parallel (the northernmost portion of the Mississippi River watershed, including those parts of the Milk River, Poplar River, and Big Muddy Creek watersheds in modern-day Alberta and Saskatchewan). The article settled a boundary dispute caused by ignorance of actual geography in the boundary agreed to in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolutionary War. The earlier treaty had placed the boundary between the United States and British North America along a line extending westward from the Lake of the Woods to the Mississippi River. The parties did not realize that the river did not extend that far north and so such a line would never meet the river. In fixing the problem, the 1818 treaty created a pene-enclave of the United States, the Northwest Angle, the small section of the present state of Minnesota that is the only part of the United States apart from Alaska that lies north of the 49th parallel.

- Article III provided for joint control of land in the Oregon Country for ten years. Both could claim land and were guaranteed free navigation throughout.

- Article IV confirmed the Anglo-American Convention of 1815,[5] which regulated commerce between the two parties, for an additional ten years.

- Article V agreed to refer differences over a US claim arising from the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812, to "some Friendly Sovereign or State to be named for that purpose." The claim in question was for the return of or compensation for American slaves who had escaped to British-controlled territory or Royal Navy warships when the treaty was signed. The article in question was about handing over property, and the US government claimed that the slaves were the property of its citizens.[3]

- Article VI established that ratification would occur within six months of signing the treaty.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

The treaty was negotiated for the US by Albert Gallatin, ambassador to France, and Richard Rush, minister to the UK; and for the UK by Frederick John Robinson, Treasurer of the Royal Navy and member of the privy council, and Henry Goulburn, an undersecretary of state.[4] The treaty was signed on October 20, 1818. Ratifications were exchanged on January 30, 1819.[1] The Convention of 1818, along with the Rush–Bagot Treaty of 1817, marked the beginning of improved relations between the British Empire and its former colonies, and paved the way for more positive relations between the US and Canada although repelling a US invasion was a defense priority in Canada until 1928.[6]

Despite the relatively friendly nature of the agreement, it resulted in a fierce struggle for control of the Oregon Country for the following two decades. The British-chartered Hudson's Bay Company, having previously established a trading network centered on Fort Vancouver on the lower Columbia River, with other forts in what is now eastern Washington and Idaho as well as on the Oregon Coast and in Puget Sound, undertook a harsh campaign to restrict encroachment by US fur traders to the area. By the 1830s, the policy of discouraging settlement was undercut to some degree by the actions of John McLoughlin, Chief Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver, who regularly provided relief and welcome to US immigrants who had arrived at the post over the Oregon Trail.

By the mid-1840s, the tide of US immigration, as well as a US political movement to claim the entire territory, led to a renegotiation of the agreement. The Oregon Treaty in 1846 permanently established the 49th parallel as the boundary between the United States and British North America to the Pacific Ocean.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, between the U.S. and Spain, resolved borders from Florida to the Pacific Ocean.

- The Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842 resolved uncertainties left by the 1818 treaty, including the Northwest Angle problem, which had been created by the use of a faulty map.

- Oregon boundary dispute, concerning the joint occupation of the Oregon Country by U.S. and British settlers.

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which established most of the southern border between the US and Mexico after the defeat and occupation of Mexico in 1848, ending the Mexican–American War.

- The Gadsden Purchase, which completed the acquisition of the southwestern United States and completed the border between Mexico and the US in 1853 at the 32nd parallel and the Rio Grande.

References

[edit]- ^ a b United States Department of State (2007-11-01). Treaties In Force: A List of Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States in Force on November 1, 2007. Section 1: Bilateral Treaties (PDF). Compiled by the Treaty Affairs Staff, Office of the Legal Adviser, U.S. Department of State. (2007 ed.). Washington, DC. p. 320. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^

Lauterpacht, Elihu, et al., ed. (2004). "Consolidated Table of Treaties, Volumes 1-125" (PDF). In Elihu Lauterpacht; C. J. Greenwood; A. G. Oppenheimer; Karen Lee. (eds.). International Law Reports. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-521-80779-4. Retrieved 2006-03-27.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c LexUM (2000). "Convention of Commerce between His Majesty and the United States of America.--Signed at London, 20th October, 1818". Canado-American Treaties. University of Montreal. Archived from the original on April 11, 2009. Retrieved 2006-03-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b LexUM (1999). "CUS 1818/15 Subject: Commerce". Canado-American Treaties. University of Montreal. Archived from the original on March 25, 2009. Retrieved 2006-03-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Article on "The Convention of 1815", The Marine Journal, June 3, 1922

- ^ Preston, Richard A. The Defence of the Undefended Border: Planning for War in North America 1867–1939, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1977

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920. This article traces British-United States negotiations regarding ocean fisheries from 1783 to 1910.

- 1818 in London

- 1818 in the United States

- 1818 treaties

- October 1818 events

- Canada–United States border

- Pre-statehood history of Oregon

- Oregon Country

- Legal history of Canada

- Boundary treaties

- Treaties involving territorial changes

- Pre-Confederation British Columbia

- Pre-statehood history of Minnesota

- 15th United States Congress

- United States slavery law

- United Kingdom–United States treaties

- Treaties of the United Kingdom (1801–1922)

- F. J. Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich