Mid-Atlantic Ridge

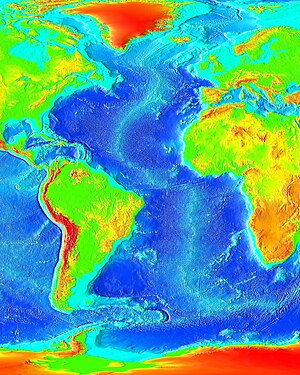

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a divergent or constructive plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. In the North Atlantic, the ridge separates the North American from the Eurasian Plate and the African Plate, north and south of the Azores Triple Junction. In the South Atlantic, it separates the African and South American plates. The ridge extends from a junction with the Gakkel Ridge (Mid-Arctic Ridge) northeast of Greenland southward to the Bouvet Triple Junction in the South Atlantic. Although the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is mostly an underwater feature, portions of it have enough elevation to extend above sea level, for example in Iceland. The ridge has an average spreading rate of about 2.5 centimetres (1 in) per year.[1]

Discovery

[edit]

A ridge under the northern Atlantic Ocean was first inferred by Matthew Fontaine Maury in 1853, based on soundings by the USS Dolphin. The existence of the ridge and its extension into the South Atlantic was confirmed during the expedition of HMS Challenger in 1872.[2][3] A team of scientists on board, led by Charles Wyville Thomson, discovered a large rise in the middle of the Atlantic while investigating the future location for a transatlantic telegraph cable.[4] The existence of such a ridge was confirmed by sonar in 1925[5] and was found to extend around Cape Agulhas into the Indian Ocean by the German Meteor expedition.[6]

In the 1950s, mapping of the Earth's ocean floors by Marie Tharp, Bruce Heezen, Maurice Ewing, and others revealed that the Mid-Atlantic Ridge had a strange bathymetry of valleys and ridges,[7] with its central valley being seismologically active and the epicenter of many earthquakes.[8][9] Ewing, Heezen and Tharp discovered that the ridge is part of a 40,000-km (25,000 mile) long essentially continuous system of mid-ocean ridges on the floors of all the Earth's oceans.[10] The discovery of this worldwide ridge system led to the theory of seafloor spreading and general acceptance of Alfred Wegener's theory of continental drift and expansion in the modified form of plate tectonics. The ridge is central to the breakup of the hypothetical supercontinent of Pangaea that began some 180 million years ago.

Notable features

[edit]The Mid-Atlantic Ridge includes a deep rift valley that runs along the axis of the ridge for nearly its entire length. This rift marks the actual boundary between adjacent tectonic plates, where magma from the mantle reaches the seafloor, erupting as lava and producing new crustal material for the plates.

Near the equator, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is divided into the North Atlantic Ridge and the South Atlantic Ridge by the Romanche Trench, a narrow submarine trench with a maximum depth of 7,758 m (25,453 ft), one of the deepest locations of the Atlantic Ocean. This trench, however, is not regarded as the boundary between the North and South American Plates, nor the Eurasian and African Plates.

Islands

[edit]

The islands on or near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, from north to south, with their respective highest peaks and location, are:

Northern Hemisphere (North Atlantic Ridge):

- Jan Mayen (Beerenberg, 2277 metres (7470') (at 71°06′N 08°12′W / 71.100°N 8.200°W), in the Arctic Ocean

- Iceland (Hvannadalshnúkur at Vatnajökull, 2109.6 metres (6921') (at 64°01′N 16°41′W / 64.017°N 16.683°W), through which the ridge runs

- Azores (Ponta do Pico or Pico Alto, on Pico Island, 2351 metres (7713'), (at 38°28′0″N 28°24′0″W / 38.46667°N 28.40000°W)

- Saint Peter and Paul Rocks (Southwest Rock, 22.5 metres (74'), at 00°55′08″N 29°20′35″W / 0.91889°N 29.34306°W)

Southern Hemisphere (South Atlantic Ridge):

- Ascension Island (The Peak, Green Mountain, 859 metres (2818'), at 07°59′S 14°25′W / 7.983°S 14.417°W)

- Saint Helena (Diana's Peak, 818 metres (2684') at 15°57′S 5°41′W / 15.950°S 5.683°W)

- Tristan da Cunha (Queen Mary's Peak, 2062 metres (6765'), at 37°05′S 12°17′W / 37.083°S 12.283°W)

- Gough Island (Edinburgh Peak, 909 metres (2982'), at 40°20′S 10°00′W / 40.333°S 10.000°W)

- Bouvet Island (Olavtoppen, 780 metres (2560'), at 54°24′S 03°21′E / 54.400°S 3.350°E)

Iceland

[edit]The submarine section of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge close to southwest Iceland is known as the Reykjanes Ridge. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge runs through Iceland where the ridge is also known as the Neovolcanic Zone. In northern Iceland the Tjörnes Fracture Zone connects Iceland to the Kolbeinsey Ridge.

Geology

[edit]

The ridge sits atop a geologic feature known as the Mid-Atlantic Rise, which is a progressive bulge that runs the length of the Atlantic Ocean, with the ridge resting on the highest point of this linear bulge. This bulge is thought to be caused by upward convective forces in the asthenosphere pushing the oceanic crust and lithosphere. This divergent boundary first formed in the Triassic period, when a series of three-armed grabens coalesced on the supercontinent Pangaea to form the ridge. Usually, only two arms of any given three-armed graben become part of a divergent plate boundary. The failed arms are called aulacogens, and the aulacogens of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge eventually became many of the large river valleys seen along the Americas and Africa (including the Mississippi River, Amazon River and Niger River). The Fundy Basin on the Atlantic coast of North America between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in Canada is evidence of the ancestral Mid-Atlantic Ridge.[12][13]

See also

[edit]- Atlantis Massif

- Canadian Arctic Rift System

- Central Atlantic Magmatic Province

- Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone

- East Pacific Rise

- Fifteen-Twenty Fracture Zone

- Project FAMOUS

- Researcher Ridge

References

[edit]- ^ USGS (5 May 1999). "Understanding plate motions". Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Searle, R. (2013). Mid-Ocean Ridges. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9781107017528.

- ^ Hsü, Kenneth J. (1992). Challenger at Sea: A Ship That Revolutionized Earth Science. Princeton University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-691-08735-1.

- ^ Redfern, R.; 2001: Origins, the Evolution of Continents, Oceans and Life, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 1-84188-192-9, p. 26

- ^ Alexander Hellemans and Brian Bunch, 1989, Timeline of Science, Sidgwick and Jackson, London

- ^ "Stein, Glenn, A Victory in Peace: The German Atlantic Expedition 1925–27, June 2007". Archived from the original on 2016-03-09. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ^ Ewing, W.M.; Dorman, H.J.; Ericson, J.N.; Heezen, B.C. (1953). "Exploration of the northwest Atlantic mid-ocean canyon". Bulletin of the Geological Society of America. 64 (7): 865–868. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1953)64[865:eotnam]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Heezen, B. C.; Tharp, M. (1954). "Physiographic diagram of the western North Atlantic". Bulletin of the Geological Society of America. 65: 1261.

- ^ Hill, M.N.; Laughton, A.S. (1954). "Seismic Observations in the Eastern Atlantic, 1952". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 222 (1150): 348–356. Bibcode:1954RSPSA.222..348H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1954.0078. S2CID 140604584.

- ^ Spencer, Edgar W. (1977). Introduction to the Structure of the Earth (2nd ed.). Tokyo: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-085751-3.

- ^ General citations for named fracture zones are at page Wikipedia:Map data/Fracture zone and specific citations are in interactive detail.

- ^ Burke, K.; Dewey, J. F. (1973). "Plume-generated triple junctions: key indicators in applying plate tectonics to old rocks" (PDF). The Journal of Geology. 81 (4): 406–433. Bibcode:1973JG.....81..406B. doi:10.1086/627882. JSTOR 30070631. S2CID 53392107. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-23. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- ^ Burke, K. (1976). "Development of graben associated with the initial ruptures of the Atlantic Ocean". Tectonophysics. 36 (1–3): 93–112. Bibcode:1976Tectp..36...93B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.473.8997. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(76)90009-3.

Bibliography

[edit]- Evans, Rachel. "Plumbing Depths to Reach New Heights: Marie Tharp Explains Marine Geological Maps." The Library of Congress Information Bulletin. November 2002.