France–Morocco relations

| |

France |

Morocco |

|---|---|

France–Morocco relations are bilateral relations between Morocco and France. They are part of the France–Africa relations.

First exchanges (8th century)

[edit]

Following the invasion of Spain from the coast of Morocco by the Umayyad Commander Tariq ibn Ziyad in 711, during the 8th century the Arab caliphate armies invaded Southern France, as far as Poitiers and the Rhône valley as far as Avignon, Lyon, Autun, until the turning point of the Battle of Tours in 732.[1]

France would again become threatened by the proximity of the expanding Almoravid Empire in the 11th and 12th centuries.[2]

Consuls and physicians (1577–1600)

[edit]

In 1402, the French adventurer Jean de Béthencourt left La Rochelle and sailed along the coast of Morocco to conquer the Canary islands.[3]

In the 16th century, the sealing of a Franco-Ottoman alliance between Francis I and Suleiman the Magnificent permitted numerous contacts between French traders and countries under Ottoman influence. In 1533, Francis I sent colonel Pierre de Piton as ambassador to Morocco.[4] In a letter to Francis I dated August 13, 1533, the Wattassid ruler of Fes, Ahmed ben Mohammed, welcomed French overtures and granted freedom of shipping and protection to French traders. France started to send ships to Morocco in 1555, under the rule of Henry II, son of Francis I.[5]

France, under Henry III, established a Consul in Fes, Morocco, as early as 1577, in the person of Guillaume Bérard, and was the first European country to do so.[6][7] Under Henry, France named Guillaume Bérard as the first Consul of France in Morocco. Bérard, a doctor by profession, had saved the life of the Moroccan prince Abd al-Malik, during an epidemic in Istanbul; when he came to the Moroccan throne, Abd al-Malik wished to retain Bérard in his service.[8]

Bérard was succeeded by Arnoult de Lisle and then Étienne Hubert d'Orléans in the double position of physician and representative of France at the side of the Sultan. These contacts with France occurred during the landmark rules of Abd al-Malik and his successor, Moulay Ahmad al-Mansur.

This was also a time when England was trying to establish friendly relations with Morocco as well, in view of an Anglo-Moroccan alliance, with the visit of Edmund Hogan to meet Muley Abd el-Malek in 1577.[7]

King Henry IV encouraged trade with faraway lands after he had ended of the French Wars of Religion (Edict of Nantes 1598).

Moroccan missions to France

[edit]The first Moroccan mission to France was that by Al-Hajari in 1610–11, who was sent to Europe by the Moroccan ruler to obtain redress against the ill-treatment of the Moriscos.[9] Soon after, Ahmed el-Guezouli visited France in 1612–1613. He first went with Nasser Carta to the Netherlands, where he obtained the intercession of the States General for a visit to France; and then to France where he endeavoured to obtain the restitution of the library of Moulay Zidane, which had been taken by Jean Philippe de Castelane.

Expeditions of Isaac de Razilly (1619-1631)

[edit]

Isaac de Razilly, accompanied by Claude du Mas, already sailed to Morocco in 1619, under the orders of Louis XIII who was considering a colonial venture in Morocco.[10] He was able to reconnoiter the coast as far as Mogador. They returned to France accompanied by an envoy in the person of caid Sidi Farès, whose mission was to take back the books of Mulay Zidan.

In 1624, Razilly was put in charge of an embassy to the pirate harbor of Salé in Morocco, in order to again solve the affair of the library of Mulay Zidan. He was imprisoned and put under chains before being released, although he had to leave many Christian captives behind.[11] The mission of Razilly was accompanied by the first Capuchins to establish themselves in Morocco.[12]

As Richelieu and Père Joseph were attempting to establish a colonial policy, Razilly suggested them to occupy Mogador in Morocco in 1626. The objective was to create a base against the Sultan of Marrakesh, and asphyxiate the harbor of Safi. He departed for Salé on 20 July 1629 with a fleet composed of the ships Licorne, Saint-Louis, Griffon, Catherine, Hambourg, Sainte-Anne, Saint-Jean. He bombarded the city the Salé and destroyed 3 corsair ships, and then sent the Griffon under Treillebois to Mogador. The men of Razilly saw the fortress of Castelo Real in Mogador, and landed 100 men with wood and supplies on Mogador island, with the agreement of Richelieu. After a few days however, the Griffon reembarked the colonists, and departed to rejoin the fleet in Salé.[13]

In 1630, Razilly was able to negotiate the purchase of French slaves from the Moroccans. He visited Morocco again in 1631, and participated to the negotiation of the Franco-Moroccan Treaty of 1631, with the help of descendants of Samuel Pallache (see Pallache family).[14] The Treaty give France preferential treatment, known as Capitulations: preferential tariffs, the establishment of a Consulate and freedom of religion for French subjects.[15]

Alliances

[edit]Early embassies

[edit]

As early as the 17th century, Moulay Ismaïl, who was looking for allies against Spain, had excellent relations with Louis XIV of France. He sent to the Sun-King ambassador Mohammad Temim in 1682. There was cooperation in several fields. French officers trained the Moroccan army and advised the Moroccans in the building of public works. French Consuls in Morocco were assigned, such as Jean-Baptiste Estelle. The French ambassador François Pidou de Saint Olon, was sent by Louis XIV visited Moulai Ismael in 1693. The Ambassador of Morocco Abdallah bin Aisha also visited Paris in 1699.[16]

Collaboration

[edit]After the end of the Seven Years' War, France turned its attention to Barbaresque pirates, especially those of Morocco, who had taken advantage of the conflict to attack Western shipping.[17] The French fleet failed in the Larache expedition in 1765.[17]

Some contacts continued during the 18th century, as when the French engineer Théodore Cornut designed the new harbour of Essaouira for King Mohammed ben Abdallah from 1760. In 1767, France established a treaty with Morocco, which gave her consular and diplomatic protection. This treaty would become a model for other European powers for the following years.[6]

In 1777, Mohammed ben Abdallah further sent an embassy to Louis XVI, led by Tahar Fennich and Haj Abdallah. The embassy brought as presents 20 French slaves previously captured in Provence by the pirates of Salé, as well as 6 magnificent horses. The two ambassadors remained in France for 6 months.[18]

Another Moroccan embassy to France in 1781 was sent, but failed to be recognized on the pretext that the title of the king of France had not been properly rendered.

Industrial era

[edit]First Franco-Moroccan War

[edit]

After the troubled periods of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, France again showed a strong interest in Morocco in the 1830s, as a possible extension of her sphere of influence in the Maghreb, after Algeria and Tunisia. The First Franco-Moroccan War took place in 1844, as a consequence of Morocco's alliance with Algeria's Abd-El-Kader against France. Following several incidents at the border between Algeria and Morocco, and the refusal of Morocco to abandon its support to Algeria, France faced Morocco victoriously in the Bombardment of Tangiers (August 6, 1844), the Battle of Isly (August 14, 1844), and the Bombardment of Mogador (August 15–17, 1844).[19] The war was formally ended September 10 with the signing of the Treaty of Tangiers, in which Morocco agreed to arrest and outlaw Abd-El-Kader, reduce the size of its garrison at Oujda, and establish a commission to demarcate the border. The border, which is essentially the modern border between Morocco and Algeria, was agreed in the Treaty of Lalla Maghnia.

In the aftermath of the war, Sultan Abd al-Rahman sent a mission to France in 1845 led by Ambassador ʿAbd al-Qādir ʾAshʿāsh of Tetuan.[20] The visit was described by the faqih and royal scribe Muḥammad Bin Abdellah aṣ-Ṣaffār in ar-Rihla at-Tetuania Ila ad-Diar al-Faransia (الرحلة التطوانية إلى الديار الفرنسية The Tetuani Journey to the French Abodes) in a lone manuscript for the sultan.[20][21]

French conquest of Morocco

[edit]The United Kingdom recognized France's "sphere of influence" in Morocco in the 1904 Entente Cordiale, provoking a German reaction. The First Moroccan Crisis of 1905-1906 was resolved at the Algeciras Conference in 1906. The Treaty of Algeciras formalized France's preeminence among European powers in Morocco, and gave France a number of colonial privileges: control over duties at Moroccan ports, a contract to develop the ports of Casablanca and Asfi, and joint control with Spain over policing in Morocco.[22]

The French military conquest of Morocco began in March 1907 when General Lyautey occupied Oujda, ostensibly in response to the murder of the French doctor Émile Mauchamp in Marrakesh.[23] A western front was opened in August 1907 with the Bombardment of Casablanca and the following "pacification of the Chawiya."[22]

The Second Moroccan Crisis, or the Agadir Crisis—in which France sent a large number of troops to Fes and Germany responded by sending a gunboat to Agadir and threatening with war—increased European Great Power tensions. It was resolved with the Franco-German Treaty of November 4, 1911.[24]

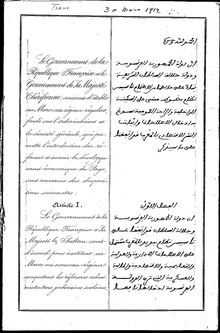

Colonial period

[edit]

The Treaty of Fes (March 30, 1912) made Morocco a French protectorate. From a strictly legal point of view, the treaty did not deprive Morocco of its status as a sovereign state.

Even after the Treaty of Fes, France waged wars of conquest in Morocco, notably the Zaian War in the Atlas and the Rif War in the north.

World War I

[edit]

France recruited infantry from its colony in Morocco to join its troupes coloniales, as it did in its other colonies in Africa and around the world. Throughout World War I, a total of 37,300-45,000 Moroccans fought for France, forming a "Moroccan Brigade."[26][27] Moroccan colonial troops first served France in the First Battle of the Marne, September 1914,[27] and participated in every major battle in the war,[28] including in Artois, Champagne, and Verdun.[26] Brahim El Kadiri Boutchich identified the participation of Moroccan soldiers in the service of France in WWI as "one of the most important moments in the shared history of Morocco and France."[26]

Independence

[edit]In late 1955, King Mohammed V successfully negotiated the gradual restoration of Moroccan independence within a framework of French-Moroccan interdependence.

Post-independence

[edit]

On October 22, 1956, French forces hijacked a Moroccan airplane carrying leaders of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) during the ongoing Algerian War.[29][30][31] Mohammed V supported the FLN in the struggle for Algerian Independence and offered to facilitate the participation of FLN leaders in a conference with Habib Bourguiba in Tunis.[30] The plane, which was carrying Ahmed Ben Bella, Hocine Aït Ahmed, and Mohamed Boudiaf, was destined to leave from Palma de Mallorca for Tunis, but French forces redirected the flight to occupied Algiers, where the FLN leaders were arrested.[30] In the aftermath, Anti-French riots in and around Meknes led to dozens of casualties.[32]

Mehdi Ben Barka was a Moroccan politician, head of the left-wing National Union of Popular Forces (UNPF) and secretary of the Tricontinental Conference. An opponent of King Hassan II, he "disappeared" in Paris in 1965.

On March 3, 1973, King Hassan II announced the policy of Moroccanization, in which state-held assets, agricultural lands, and businesses that were more than 50 percent foreign-owned—and especially French-owned—were transferred to political loyalists and high-ranking military officers.[33][34] The Moroccanization of the economy affected thousands of businesses and the proportion of industrial businesses in Morocco that were Moroccan-owned immediately increased from 18% to 55%.[33]

Current relations

[edit]Current relations between France and Morocco have been characterized as neocolonial.[35] As a francophone former colony (that nominally kept its independence) of France, Morocco falls into the cadre of Françafrique, a term used to refer to often neocolonial relations between France and its former colonies in Africa.[36] These relations between the French Republic and the Kingdom of Morocco exist mainly in the domains of trade, investment, infrastructure, education, and tourism.

In 2021, the French government determined to "drastically" reduce the number of visas issued to Moroccan citizens (as well as Algerians and Tunisians), arguing the lack of collaboration from those countries vis-à-vis deportations from France.[37][38]

In November of the same year, relations cooled due to the incidents on the Ceuta border, the resurgence of the debate on the sovereignty of Western Sahara and the conflictive diplomatic situation of Morocco with all its neighbors, especially Algeria.[39][40]

On 10 February 2023, King Mohammed VI, Terminated Mohamed Benchaaboun Duties as Ambassador to France. The termination took effect on the same day as the European Parliament’s decision to vote on a hostile resolution that accused Morocco of intimidating and harassing journalists and activists.[41][42] On 27 February 2023, Emmanuel Macron stated, “We will move forward. The stage is not the best, but this will not stop me”, in order to have good relations with Morocco.[43][44]

Economy

[edit]Morocco is the main recipient of French investment on the African continent,[45] and France remains Morocco's primary foreign investor, primary trade partner, and primary creditor—by far.[46] French foreign direct investment is present in every sector of the Moroccan economy, including the national airline, Royal Air Maroc, and the national rail network, ONCF.[46] Moroccans do also invest in France; for example, the Royal Moroccan Air Force depends on French aeronautical technologies. Over 750 subsidiaries of French companies—such as Orange, Total, and Lydec—are present in Morocco, employing around 80,000 people.[45]

As the kingdom's primary trade partner, France benefits from Morocco's lack of energy reserves and food security—which create a constant dependency on foreign trade and a permanent trade deficit in Morocco.[46] In 2008, Morocco exported $15 billion of goods and services while it imported $35 billion—primarily from France.[46]

Education

[edit]Morocco also imports education from France. To this day, French schools, which are colloquially referred to as la mission—whether they're actually related to Mission Laïque Française or not—and in which French is the language of instruction and Arabic is only taught as a second language, still have a major presence in Morocco. The schools are certified by the Agency for French Education Abroad, and administered by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the student body is typically composed of the children of Morocco's elite and well-to-do classes.[47] These schools, such as Lycée Lyautey in Casablanca, are typically located in big cities such as Casablanca, Rabat, Fes, Marrakesh, Meknes, and Oujda.[48]

France is the number 1 destination for Moroccan students leaving the country to study abroad, receiving 57.7% of all Moroccans studying outside of Morocco. Moroccan students also represent the largest group of foreign students in France, at 11.7% of all international students at universities in France, according to a 2015 UNESCO study.[49]

According to a study published in 2019, 35% of Moroccans speak French—more than Algeria at 33%, and Mauritania at 13%.[50]

There are approximately 1,514,000 Moroccans living in France, representing the largest community of Moroccans outside of Morocco.[51] The INSEE announced that there are approximately 755,400 Moroccan nationals residing in France as of October 2019, representing 20% of France's immigrant population.[52] King Mohammed VI chose France as his first state visit and the French President returned the favor. France financed 51% of the Al-Boraq high speed rail project, which was inaugurated by King Muhammad VI and President Emmanuel Macron on November 15, 2018.[53][54]

Sport

[edit]The Morocco national football team in recent years has featured a significant number of players born in France. The squad for the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations featured 10 French-born players. Eight of the players selected for the 2018 World Cup were born in France.

During the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris, Morocco provides security assistance to France including security personnel and bomb disposal officers.[55][56]

Resident diplomatic missions

[edit]

|

|

-

Embassy of France in Rabat

-

Embassy of Morocco in Paris

-

Consulate-General of Morocco in Lyon

-

Consulate-General of Morocco in Pontoise

-

Consulate-General of Morocco in Rennes

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Tricolor and crescent: France and the Islamic world by William E. Watson p.1

- ^ Reconquest and crusade in medieval Spain by Joseph F. O'Callaghan p.31

- ^ Canary Islands by Sarah Andrews, Josephine Quintero p. 25

- ^ "Francois I, hoping that Morocco would open up to France as easily as Mexico had to Spain, sent a commission, half commercial and half diplomatic, which he confided to one Pierre de Piton. The story of his mission is not without interest" in The conquest of Morocco by Cecil Vivian Usborne, S. Paul & co. ltd., 1936, p. 33

- ^ Travels in Morocco, Volume 2 James Richardson p. 32

- ^ a b The International City of Tangier, Stuart, p. 38

- ^ a b Studies in Elizabethan Foreign Trade p. 149

- ^ Garcés, María Antonia (2005). Cervantes in Algiers: a captive's tale. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 277 note 39. ISBN 9780826514707.

- ^ The mirror of Spain, 1500-1700: the formation of a myth by J. N. Hillgarth

- ^ "The narrative really begins in 1619, when the adventurer, Admiral S. John de Razilly, resolved to go to Africa. France had no colony in Morocco; hence, King Louis XIII gave whole-hearted support to de Razilly." in Round table of Franciscan research, Volumes 17-18 Capuchin Seminary of St. Anthony, 1952

- ^ The chevalier de Montmagny (1601-1657): first governor of New France by Jean-Claude Dubé, Elizabeth Rapley p.111

- ^ "The first Capuchin missionaries arrived in Morocco in 1624. They were Pierre d'Alencon, Michel de Vezins, priests, and Frère Rudolphe d'Angers a lay-brother. They were attached to the expedition of the seigneur de Razilly who was sent by France to negotiate a trade-treaty." in The Capuchins: a contribution to the history of the Counter-Reformation Father Cuthbert (O.S.F.C.) Sheed and Ward, 1928

- ^ E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 9 by Martijn Theodoor Houtsma p.549

- ^ A man of three worlds Mercedes García-Arenal, Gerard Albert Wiegers p.114

- ^ France in the age of Louis XIII and Richelieu by Victor Lucien Tapié p.259

- ^ Pennell, C.R. (2003). Morocco: from empire to independence. Oxford: Oneworld. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-85168-303-1.

- ^ a b Admiral de Grasse and American independence by Charles A. Lewis, Charles Lee Lewis p.41ff

- ^ In the lands of the Christians: Arabic travel writing in the seventeenth century by Nabil I. Matar p.191 Note 4

- ^ Navies in modern world history Lawrence Sondhaus p.71ff

- ^ a b Ṣaffār, Muḥammad, activeth century (1992). Disorienting encounters : travels of a Moroccan scholar in France in 1845-1846 : the voyage of Muḥammad aṣ-Ṣaffār. Susan Gilson Miller. Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-07461-0. OCLC 22906522.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ قرن., صفار، محمد،, 19 (2007). رحلة الصفار الى فرنسا، 1845-1846. Dār al-Suwaydī lil-Nashr wa-al-Tawzīʻ. ISBN 978-9953-36-976-1. OCLC 191967707.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Adam, André (1963). Histoire de Casablanca: des origines à 1914. Aix En Provence: Annales de la Faculté des Lettres Aix En Provence, Editions Ophrys. pp. 103–135.

- ^ Yabiladi.com. "29 mars 1907 : Quand la France occupait Oujda en réponse à l'assassinat d'Émile Mauchamp". www.yabiladi.com (in French). Retrieved 2019-06-23.

- ^ Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. XV, 106–107. ISBN 9781139624695. OCLC 855022840.

- ^ Nicolas Alexandre; Emmanuel Neiger (2014), "Le Monument à la Victoire et à la Paix de Paul Landowski. Une découverte récente à Casablanca", In Situ: Revue des patrimoines, 25

- ^ a b c الأشرف, الرباط ــ حسن. "الجنود المغاربة في الحرب العالمية الأولى: أبطال بلا مجد". alaraby (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- ^ a b "Exhibition of Moroccan Art". www.wdl.org. 1917. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- ^ "Guerre de 1914-18: les soldats marocains "dans toutes les grandes batailles"". LExpress.fr (in French). 2018-11-01. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- ^ Essemlali, Mounya (2011). "Le Maroc entre la France et l'Algérie (1956-1962)". Relations Internationales. 146 (2): 77. doi:10.3917/ri.146.0077. ISSN 0335-2013.

- ^ a b c Yabiladi.com. "22 October 1956 : Ben Bella, King Mohammed V and the story of the re-routed plane". en.yabiladi.com. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Essa (2020-10-22). "أكتوبر في تاريخ المغرب أحداث وأهوال | المعطي منجب". القدس العربي (in Arabic). Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ Largeaud, Jean-Marc (2016-07-28). "Violences urbaines, Maroc 1956". Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l'Ouest (123–2): 107–129. doi:10.4000/abpo.3306. ISSN 0399-0826.

- ^ a b Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 184. ISBN 9781139624695. OCLC 855022840.

- ^ "Marocanisation : Un système et des échecs". Aujourd'hui le Maroc (in French). Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Zakhir, Marouane; O’Brien, Jason L. (2017-02-01). "French neo-colonial influence on Moroccan language education policy: a study of current status of standard Arabic in science disciplines". Language Policy. 16 (1): 39–58. doi:10.1007/s10993-015-9398-3. ISSN 1573-1863.

- ^ "Françafrique: A brief history of a scandalous word". newafricanmagazine.com. 23 March 2018. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Réduction des visas accordés au Maroc et à l'Algérie : "On met nos menaces à exécution"". Europe 1. 28 September 2021.

- ^ Gatinois, Claire; Bobin, Frédéric; Kadiri, Ghalia (28 September 2021). "Immigration : la France durcit " drastiquement " l'octroi de visas aux Algériens, Marocains et Tunisiens". Le Monde.

- ^ "Things are heating up in Western Sahara". The Economist. 2021-11-06. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ "Why is the Western Sahara conflict heating up?". France 24. 2021-11-06. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ^ Kasraoui, Safaa. "King Mohammed VI Terminates Benchaaboun's Duties as Ambassador to France". moroccoworldnews. Retrieved 2023-02-12.

- ^ "Moroccan ambassador to France relieved of his duties, on day of EP resolution". HESPRESS English - Morocco News. 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2023-02-12.

- ^ "Macron admits to crisis with Morocco, says he is determined to patch up strained relations with African nations". HESPRESS English - Morocco News. 2023-02-27. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ^ Kasraoui, Safaa. "Emmanuel Macron Blames Unspecified Parties for Morocco-France Tensions". moroccoworldnews. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ^ a b Lahsini, Chaima (2017-06-15). "France-Morocco: A Rich Past and a Promising Future|Bilateral Relations". Morocco World News. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 231. ISBN 9781139624695. OCLC 855022840.

- ^ Ennaji, Moha (2005-01-20). Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 37. ISBN 9780387239798.

- ^ Ennaji, Moha (2005-01-20). Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 106. ISBN 9780387239798.

- ^ "Campus France Chiffres Cles August 2018" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-17. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Koundouno, Tamba François (2019-03-20). "International Francophonie Day: 35% Moroccans Speak French". Morocco World News. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- ^ Fiches thématiques - Population immigrée - Immigrés - Insee Références - Édition 2012, Insee 2012 Archived 13 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hekking, Morgan (2019-10-09). "Moroccans Make Up Nearly 20% of France's Immigrant Population". Morocco World News. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- ^ "Economic relations - France-Diplomatie". www.diplomatie.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 2012-11-17.

- ^ H24info. "LGV: Al Bouraq fait entrer le Maroc dans une nouvelle ère | H24info" (in French). Retrieved 2019-06-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "France commends Morocco's support in counterterrorism efforts ahead of 2024 Paris Olympics". RFI. 2024-04-24. Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- ^ "Paris 2024: Moroccan police officers and bomb disposal experts to support French forces". Le Monde.fr. 2024-04-24. Retrieved 2024-07-29.