Saint Helena

Saint Helena | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Loyal and Unshakable" | |

| Anthem: "God Save the King" | |

| Unofficial anthem: "My Saint Helena Island" | |

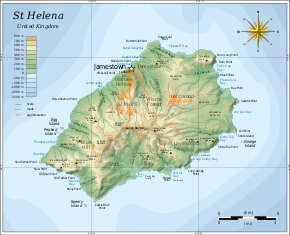

Map of Saint Helena | |

Location of Saint Helena in the southern Atlantic Ocean | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Colonial charter | 1657 |

| Crown colony | 22 April 1834[1] |

| Current constitution | 1 September 2009 |

| Capital | Jamestown 15°56′S 05°43′W / 15.933°S 5.717°W |

| Largest city | Half Tree Hollow 15°56′0″S 5°43′12″W / 15.93333°S 5.72000°W |

| Official languages | English |

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Devolved parliamentary dependency under a constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

• Governor | Nigel Phillips |

| Julie Thomas | |

| Legislature | Legislative Council |

| Government of the United Kingdom | |

• Minister | Vacant |

| Area | |

• Total | 121.8 km2 (47.0 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 820 m (2,690 ft) |

| Population | |

• 2021 census | 4,439[2] |

• Density | 36.5/km2 (94.5/sq mi) |

| Currency | Pound sterling Saint Helena pound (£) (SHP) |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (GMT) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +290 |

| ISO 3166 code | |

| Internet TLD | .sh |

Saint Helena (/ˌsɛnt (h)ɪˈliːnə, ˌsɪnt-, sənt-/, US: /ˌseɪnt-/[3][4]) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha,[5] a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km (1,165 miles) west of mainland Africa, with Angola and Namibia being the closest nations, geographically. The island is located around 1,950 km (1,210 mi) west of the coast of southwestern South Africa, and 4,000 km (2,500 mi) east of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Until 2018, the primary method of reaching Saint Helena was by booking a spot on the RMS St Helena—a cargo and post delivery vessel that also ferried visitors—which routinely made the 3,141 km (1,951 mi), six-day journey from Cape Town, South Africa.

Saint Helena measures about 16 by 8 km (10 by 5 mi) and has a population of 4,439 per the 2021 census.[2] It was named after Helena, mother of Constantine I. It is one of the most remote major islands in the world and was uninhabited when discovered by the Portuguese enroute to the Indian subcontinent in 1502. For about four centuries, the island was an important stopover for ships from Europe to Asia and back, while sailing around the African continent, until the opening of the Suez Canal. Saint Helena is the United Kingdom's second-oldest overseas territory after Bermuda.

Saint Helena is known for being the site of Napoleon's second exile, following his final defeat in 1815.

History[edit]

Discovery[edit]

According to long-established tradition, the island was sighted on 21 May 1502 by the four ships of the 3rd Portuguese Armada, commanded by João da Nova, a Galician navigator in the service of Portugal, during his return voyage to Lisbon, who named it Santa Helena after Saint Helena of Constantinople. This tradition was reviewed by a 2022 paper[6] which concluded that the Portuguese chronicles[7] published at least fifty years after the sighting are the sole primary source for the discovery. Although contradictory in describing other events, these chronicles almost unanimously claim that João da Nova found Saint Helena sometime in 1502, although none of them gives a precise date.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

However, there are several reasons to doubt that da Nova made this discovery:

- Given that da Nova returned either on 11 September[14] or on 13 September 1502[15] it is usually assumed that the Cantino planisphere, completed by the following November,[16] includes his discovery of Ascension Island (shown as an archipelago, with one of six islands marked as "ilha achada e chamada Ascenssam"), yet this map fails to show Saint Helena.[17][18]

- When a section of the Fourth Armada under the command of Estêvão da Gama sighted and landed at Saint Helena the following year on 30 July 1503, its scrivener Thomé Lopes regarded it as an unknown island, yet named Ascension as one of five reference points for the new island's location. On 12 July 1503, nearly three weeks before reaching Saint Helena, Lopes described how Estêvão da Gama's ships met up with a section of the Fifth Armada led by Afonso de Albuquerque off the Cape of Good Hope. The latter had left Lisbon about six months after João da Nova's return, so Albuquerque and his captains should all have known whether João da Nova had indeed found St Helena. An anonymous Flemish traveler on one of da Gama's ships reported that bread and victuals were running short by the time they reached the Cape, so from da Gama's perspective there was a pressing need that he be told that water and meat could be found at Saint Helena.[19] But nothing seems to have been said about the island, and Lopes regarded the island as unknown. This again implies that da Nova found Ascension but not St Helena.

The 2022 paper also reviews cartographic evidence that Saint Helena and Ascension were known to the Spanish in 1500, before either João da Nova or Estêvão da Gama sailed for India. The suggestion that da Nova discovered Tristan da Cunha and named it Saint Helena is discounted.[20][21]

A 2015 paper notes that 21 May is the feast day of St Helena in the Eastern Orthodox and most Protestant churches, but the Roman Catholic one is in August, and the day and the month were first quoted in 1596 by Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, who was probably mistaken, because the island was discovered several decades before the Reformation and the start of Linschoten's Protestant faith.[22][23][24][25] An alternative discovery date of 3 May is suggested as being historically more credible; it is the Catholic feast day of the finding of the True Cross by Saint Helena in Jerusalem, and cited by Odoardo Duarte Lopes[26] and Sir Thomas Herbert.[27]

When Linschoten arrived at the island on 12 May 1589, he reported seeing carvings made by visiting seamen on a fig tree that were dated as early as 1510.[28] The Portuguese probably planted saplings rather than mature trees, and for these to be sufficiently large by 1510 to carry carvings suggests the plants were shipped to the island and planted there some years earlier, possibly within a few years of discovery.

A third discovery story, told by 16th-century historian Gaspar Correia, holds that the island was found by Portuguese nobleman and warrior Dom Garcia de Noronha, who sighted the island on his way to India in late 1511 or early 1512. His pilots entered the island onto their charts, and this event likely led to the island being used as a regular stopover for rest and replenishment for ships en route from India to Europe, from that date until well into the 17th century.[29] An analysis has been published of the Portuguese ships arriving at Saint Helena in the period 1502–1613.[30]

Exploitation of the island[edit]

The Portuguese found the island uninhabited, with an abundance of trees and fresh water. They imported livestock, fruit trees, and vegetables, and built a chapel and one or two houses. The long tradition that João da Nova built a chapel from one of his wrecked carracks has been shown to be based on a misreading of the records.[31] They formed no permanent settlement, but the island was an important rendezvous point and source of food for ships travelling by the Cape Route from Asia to Europe, and frequently sick mariners were left on the island to recover before taking passage on the next ship to call at the island.[32]

Englishman Sir Francis Drake probably located the island on the final leg of his circumnavigation of the world (1577–1580).[33] Further visits by other British explorers followed and, once Saint Helena's location was more widely known, British ships of war began to lie in wait in the area to attack Portuguese India carracks on their way home.[34]

In developing their Far East trade, the Dutch also began to frequent the island. The Portuguese and Spanish soon gave up regularly calling at the island, partly because they used ports along the West African coast, but also because of attacks on their shipping, the desecration of their chapel and religious icons, killings of their livestock, and destruction of their plantations by Dutch pirates.[34]

The Dutch Republic formally claimed Saint Helena in 1633, although no evidence indicates they ever occupied it. The Dutch lost interest in the island after establishing their colony at the Cape of Good Hope.[34]

East India Company (1658–1815)[edit]

In 1657, Oliver Cromwell granted the East India Company (EIC) a charter to govern Saint Helena. The following year, the company decided to fortify the island and settle it with planters.[35] A theory, which had its origins in the early 20th century, that the early settlers included many who had lost their homes in the 1666 Great Fire of London, was shown to be a myth in 1999.[36]

The first governor, Captain John Dutton, arrived in 1659, making Saint Helena one of Britain's earliest colonies outside Europe, North America and the Caribbean. A fort and houses were built: Jamestown had been founded, "in the narrow valley between steep cliffs".[37]

After the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660, the EIC received a royal charter, giving it the sole right to fortify and colonise the island. The fort was renamed James Fort and the town was called Jamestown, in honour of the Duke of York, later King James II.[34]

Between January and May 1673, the Dutch East India Company seized the island, but British reinforcements restored EIC control. The island was fortified with about 230 gun turrets.[37]

The British government sent some settlers and gave them land that they could farm,[37] but the company found it hard to attract enough settlers, despite advertisements in London and free tracts of land. By 1670, the population was only 66, including slaves.[38] Also unrest and rebellion occurred among the inhabitants. Ecological problems, such as deforestation, soil erosion, vermin, and drought, led Governor Isaac Pyke to suggest in 1715 that the population be moved to Mauritius, but that was not acted upon. The company continued to subsidise the community because of the island's strategic location. A census in 1723 recorded 1,110 inhabitants, including 610 slaves.[38]

In the peak era, about 1,000 ships per year stopped there, leaving the governor to try to police the numerous visitors and to limit the consumption of arrack, a distilled alcoholic drink made from potatoes. There were two mutinies, perhaps fueled by alcohol. Because Jamestown was "too raucous with its taverns and brothels", St Paul's Cathedral was built outside the town.[39]

Eighteenth-century governors tried to tackle the island's problems by planting trees, improving fortifications, eliminating corruption, building a hospital, tackling the neglect of crops and livestock, controlling the consumption of alcohol, and introducing legal reforms. The island enjoyed a lengthy period of prosperity from about 1770. Captain James Cook visited the island in 1775 on the final leg of his second circumnavigation of the world. St. James' Church was built in Jamestown in 1774, and Plantation House in 1791–1792; the latter has since been the official residence of the governor.

Edmond Halley visited Saint Helena on leaving the University of Oxford in 1676, and set up an astronomical observatory with a 7.3-metre-long (24 ft) aerial telescope, intending to study the stars of the Southern Hemisphere.[40] The site of this telescope is near Saint Mathew's Church at Hutt's Gate in the Longwood district. The 680-metre-high (2,230 ft) hill there is called Halley's Mount.

Throughout that period, Saint Helena was an important port of call of the EIC. East Indiamen would stop there on the return leg of their voyages to British India and China. At Saint Helena, ships could replenish supplies of water and provisions and, during wartime, form convoys that would sail under the protection of vessels of the Royal Navy.

James Cook’s ship HMS Endeavour anchored and resupplied off the coast of Saint Helena in May 1771 on its return from the European discovery of the east coast of Australia and the rediscovery of New Zealand.[41]

The British brought an estimated 27,000 slaves from west Africa to the island, in addition to the 3,000,000 they transported to the New World. The importation of slaves was made illegal in 1792, but the horrific conditions of slavery on St Helena were not abolished until 27 May 1839, when the 'Ordinance For the Abolition of Slavery in the Island of St Helena' was enacted.[42] Rupert's Valley was the embarkation area for slaves; in 2008, when the road to the airport was being built, over 9,000 skeletal remains of slaves were uncovered in a mass burial area. They were reburied en masse in 2022 without ceremony of any kind.[43] Governor Robert Patton (1802–1807) recommended that the company import workers from China to supplement the rural workforce. Many were allowed to stay, and their descendants became integrated into the population. In 1810, Chinese labourers began arriving, and by 1818, there were 650 in St Helena.[38] An 1814 census recorded 3,507 people on the island. Many of the labourers were allowed to stay, though the need for their services had reduced by 1836.

British rule (1815–1821) and Napoleon's exile[edit]

In 1815, the British government selected Saint Helena as the place of exile for Napoleon Bonaparte, after the Battle of Waterloo, his second abdication (on 22 June 1815) and his final surrender, to Captain Frederick Maitland, on HMS Bellerophon (15 July 1815).[44] He was taken to the island in October 1815. Napoleon stayed at the Briars pavilion, on the grounds of the Balcombe family's home, until his permanent residence at Longwood House was completed in December 1815. He died there on 5 May 1821.[45]

British East India Company (1821–1834)[edit]

Following Napoleon's death, the soldiers and other temporary residents linked to his presence on the island were withdrawn and the EIC resumed full control of Saint Helena. Between 1815 and 1830, the EIC made the packet schooner St Helena available to the government of the island, which made multiple trips per year between the island and the Cape, carrying passengers both ways and supplies of wine and provisions back to the island. Napoleon praised Saint Helena's coffee during his exile on the island, and the product enjoyed a brief popularity in Paris in the years after his death.[citation needed]

The importation of slaves to Saint Helena was banned in 1792. In 1818, the governor freed children born of slaves on the island.[37] The phased emancipation of over 800 resident slaves took place in 1827, some six years before the British parliament passed legislation to abolish slavery in the colonies.[37][46]

Between 1791 and 1833, Saint Helena became the site of a series of experiments in conservation, reforestation, and attempts to boost rainfall artificially.[47] This environmental intervention was closely linked to the conceptualisation of the processes of environmental change and helped establish the roots of environmentalism.[47]

Crown colony (1834–1981)[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

Under the provisions of the 1833 India Act, control of Saint Helena passed from the EIC to the British Crown, and it became a crown colony.[1] Subsequent administrative cost-cutting triggered a long-term population decline; those who could afford to do so tended to leave the island for better opportunities elsewhere. The latter half of the 19th century saw the advent of steamships not reliant on trade winds, as well as the diversion of Far East trade away from the traditional South Atlantic shipping lanes to a route via the Red Sea (which, prior to the building of the Suez Canal, involved a short overland section).[34]

In 1840, a British naval station established to suppress the Atlantic slave trade was based on the island, and between 1840 and 1849, over 15,000 freed slaves, known as "Liberated Africans", were landed there.[34]

In 1858, French emperor Napoleon III purchased, in the name of the French government, Longwood House and the lands around it, the last residence of Napoleon I (who died there in 1821; his remains had been returned to France in 1840.)[37] It is still French property, administered by a French representative and under the authority of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

A 2020 report states that the island's prosperity ended after 1869 when "the Suez Canal shifted trade routes north". A 2019 report explained that "ships no longer needed a stopping point on a longer journey to Europe".[39][37] The number of ships calling at the island fell from 1,100 in 1855 to only 288 in 1889.[34]

On 11 April 1898, American Joshua Slocum, on his solo round-the-world voyage, arrived at Jamestown. He departed on 20 April 1898 for the final leg of his circumnavigation, having been extended hospitality by the governor, R. A. Sterndale. He presented two lectures on his voyage and was invited to Longwood by the French consular agent.[48]

By the end of 1899, St Helena was connected to London by undersea cable; this allowed for telegraph communication. In 1900 and 1901, over 6,000 Boer prisoners were held on the island, during the Second Anglo-Boer War. A 2019 report stated, "no traces remain of the two POW camps", but added, "the Boer Cemetery is a poignant spot".[39] Among the notables were Piet Cronjé and his wife after their defeat at the Battle of Paardeberg.[49][50] The resulting population reached an all-time high of 9,850 in 1901. By 1911, however, that had declined to 3,520 people. In 1906, the British government withdrew the garrison; the island's economy suffered when spending by the soldiers stopped.[38]

A local industry manufacturing fibre from New Zealand flax was successfully re-established in 1907 and generated considerable income during the First World War. Ascension Island was made a dependency of Saint Helena in 1922, and Tristan da Cunha followed in 1938. During the Second World War, the United States built Wideawake Airport on Ascension in 1942, but no military use was made of Saint Helena except maintenance of its defences.[51]

Attendance at school became mandatory in 1942, for ages 5 to 15 in 1941, and the government took over control of the education system. The first secondary school opened in 1946. The American construction of Wideawake Airfield generated numerous jobs for St Helena; the sale of flax for rope also generated revenue for the island.[38] However, the industry declined after 1951 because of transport costs and competition from synthetic fibres. The decision in 1965 by the British Post Office to use synthetic fibres for its mailbags was a further blow, contributing to the closure of the island's flax mills in 1965.

From 1958, the Union-Castle shipping line gradually reduced its service calls to the island. Curnow Shipping, based in Avonmouth, replaced the Union-Castle Line mailship service in 1977, using the RMS St Helena, which was introduced in 1989.

1981 to present[edit]

The British Nationality Act 1981 reclassified Saint Helena and the other crown colonies as British Dependent Territories.[38] For the next 20 years, many could find only low-paid work with the island government, and the only available employment outside Saint Helena was on the Falkland Islands and Ascension Island. The Development and Economic Planning Department (which still operates) was formed in 1988 to contribute to raising the living standards of the people of Saint Helena.

The Commission on Citizenship was established in 1992, restoring the islanders' rights including the right of abode. In 2002, the right to British citizenship was restored.[38]

In 1989, Prince Andrew launched the replacement RMS St Helena to serve the island; the vessel was specially built for the Cardiff–Cape Town route and featured a mixed cargo/passenger layout.

The Saint Helena Constitution took effect in 1989, and provided that the island would be governed by a governor, a commander-in-chief, and an elected executive and legislative council. In 2002, the British Overseas Territories Act 2002 granted full British citizenship to the islanders and renamed the dependent territories (including Saint Helena) the British Overseas Territories. In 2009, The St Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha Constitution Order 2009 gave all three equal status; the British Overseas Territory was renamed Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha.[52]

In 2021, a ministerial system was introduced in Saint Helena after UK's approval of a constitution amendment.[53][54]

Geography[edit]

Situated in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, more than 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) from the nearest major landmass, Saint Helena is remote. The nearest port on the continent is Moçâmedes in southern Angola; connections to Cape Town, South Africa are used for most shipping needs via the regular cargo ship that serves the island, the MS Helena.

The island is on the same ridge as two other islands in the southern Atlantic, also British territories: Ascension Island, about 1,300 kilometres (810 mi) due north-west in more equatorial waters, and Tristan da Cunha, which is outside the tropics 2,430 kilometres (1,510 mi) to the south. The island, in the Western Hemisphere, has the same longitude as Land's End (west Cornwall, England), and western Spain. For sharing several trading patterns[clarification needed], and climate effect traits, the island is grouped under West Africa/Africa in most projects, committees and papers of the United Nations.

The island is 122 km2 (47 sq mi) in area, and is composed largely of rugged terrain of volcanic origin (the last volcanic eruptions occurred about 7 million years ago).[55] Coastal areas are scattered with vegetation on volcanic rock and are warmer and drier than the centre. The highest point of the island is Diana's Peak at 818 m (2,684 ft). In 1996 it became the island's first national park. Much of the island is covered by New Zealand flax, a legacy of former industry, but there are some original trees augmented by plantations, including those of the Millennium Forest project, which was established in 2002 to replant, particularly with indigenous gumwood, part of the lost Great Wood and is now managed by the Saint Helena National Trust.

When the island was discovered, it was covered with unique indigenous vegetation, including a remarkable cabbage tree species. The island's interior must have been a dense tropical forest but the coastal areas were probably also quite green. The modern landscape is very different, with widespread bare rock in the lower areas, although inland it is green, mainly due to introduced vegetation. There are no native land mammals, but cattle, cats, dogs, donkeys, goats, mice, rabbits, rats and sheep have been introduced. The dramatic change in landscape must be attributed to these introductions. As a result, the string tree (Acalypha rubrinervis) and the Saint Helena olive (Nesiota elliptica) are now extinct, and many of the other endemic plants are threatened with extinction.

Some 22 named rocks and islets are offshore: Castle Rock, Speery Island, the Needle, Lower Black Rock, Upper Black Rock (South), Bird Island (Southwest), Black Rock, Thompson's Valley Island, Peaked Island, Egg Island, Lady's Chair, Lighter Rock (West), Long Ledge (Northwest), Shore Island, George Island, Rough Rock Island, Flat Rock (East), the Buoys, Sandy Bay Island, the Chimney, White Bird Island and Frightus Rock (Southeast) – all within one kilometre (0.62 mi) of the shore.

The national bird of Saint Helena is the Saint Helena plover, known locally as the wirebird, on account of its wire-like legs. It appears on the coat of arms of Saint Helena and on the flag.[56][57]

Climate[edit]

The climate of Saint Helena is tropical, marine and mild, tempered by the Benguela Current and trade winds that blow almost continuously.[58][59] The climate varies noticeably across the island. Temperatures in Jamestown, on the north leeward shore, are in the range 21–28 °C (70–82 °F) in the summer (January to April) and 17–24 °C (63–75 °F) during the remainder of the year. The temperatures in the central areas are, on average, 5–6 °C (9.0–10.8 °F) lower.[59] Jamestown also has a very low annual rainfall, while 750–1,000 mm (30–39 in) falls per year on the higher ground and the south coast, where it is also noticeably cloudier.[60] There are weather recording stations in the Longwood and Blue Hill districts.

Administrative divisions[edit]

Saint Helena is divided into eight districts,[61] with the majority housing a community centre. The districts also serve as statistical divisions. The island is a single electoral area and elects 12 representatives to the Legislative Council[62] of 15.

| District | Seat | Area[63] | Population | Pop./km2 2016 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | 1998 | 2008[64] | 2016[65] | 2021[66] | |||

| Alarm Forest | The Briars | 5.4 | 2.1 | 289 | 276 | 383 | 394 | 70.4 |

| Blue Hill | Blue Hill Village | 36.8 | 14.2 | 177 | 153 | 158 | 174 | 4.3 |

| Half Tree Hollow | Half Tree Hollow | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1,140 | 901 | 984 | 1,034 | 633.2 |

| Jamestown | Jamestown | 3.9 | 1.5 | 884 | 716 | 629 | 625 | 161.9 |

| Levelwood | Levelwood | 14.8 | 5.7 | 376 | 316 | 369 | 342 | 25.0 |

| Longwood | Longwood | 33.4 | 12.9 | 960 | 715 | 790 | 765 | 23.6 |

| Sandy Bay | Sandy Bay | 16.1 | 6.2 | 254 | 205 | 193 | 177 | 12.0 |

| Saint Paul's | Saint Paul's Village | 11.4 | 4.4 | 908 | 795 | 843 | 928 | 74.0 |

| Total | 123.3 | 47.6 | 5,157 | 4,257 | 4,349 | 4,439 | 35.3 | |

The difference between the total population of the Administrative Districts and that recorded in the 2016 Census arises because the census included 183 people on board the RMS St. Helena and 13 people who were on yachts in the harbour.[65]

Population[edit]

Demographics[edit]

Saint Helena was first settled by the English in 1659. As of January 2018[update], the island had a population of 4,897 inhabitants,[67] mainly descended from people from Britain, settlers ("planters") and soldiers, and slaves who were brought there from the beginning of settlement, initially from Africa (the Cape Verde Islands, Gold Coast and west coast of Africa are mentioned in early records), then India and Madagascar. The importation of slaves was made illegal in 1792.

In 1840, Saint Helena became a provisioning station for the British West Africa Squadron,[58] preventing the transportation of slaves to Brazil (mainly), and many thousands of slaves were freed on the island. These were all African, and about 500 stayed while the rest were sent on to the West Indies and Cape Town, and eventually to Sierra Leone.

Imported Chinese labourers arrived in 1810, reaching a peak of 618 in 1818, after which numbers were reduced. Only a few older men remained after the British Crown took over the government of the island from the East India Company in 1834. The majority were sent back to China, although records in the Cape suggest that they never got any farther than Cape Town. There were also a few Indian lascars who worked under the harbour master.

The citizens of Saint Helena hold British Overseas Territories citizenship. On 21 May 2002, full British citizenship was restored by the British Overseas Territories Act 2002.[68] See also British nationality law.

During periods of unemployment, there has been a long pattern of emigration from the island since the post-Napoleonic period. The majority of "Saints" emigrated to the United Kingdom, South Africa and in the early years, Australia. The population had been steadily declining since the late 1980s and dropped from 5,157 at the 1998 census to 4,257 in 2008.[64] However, as of the 2021 census, the population has risen to 4,439[2] a drop of 95 people from 2016. In the past emigration was characterised by young unaccompanied persons leaving to work on long-term contracts on Ascension and the Falkland Islands, but since "Saints" were re-awarded British citizenship in 2002, emigration to Britain by a wider range of wage-earners has accelerated due to the prospect of higher wages and better progression prospects.[citation needed] By 2018 Swindon, Wiltshire, had a concentration of people originating from Saint Helena, and therefore it got the nickname "Swindolena".[69]

Religion[edit]

Most residents are Anglican and are members of the Diocese of St Helena, which has its own bishop and includes Ascension Island. The 150th anniversary of the diocese was celebrated in June 2009.

Other Christian denominations on the island include the Roman Catholic (since 1852), the Salvation Army (since 1884), Baptist (since 1845)[70] and, in more recent times, the Seventh-day Adventist (since 1949), the New Apostolic Church, and Jehovah's Witnesses (of which one in 35 residents is a member, the highest ratio of any country).[71]

The Roman Catholics are pastorally served by the Mission sui iuris of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, whose office of ecclesiastical superior is vested in the Apostolic Prefecture of the Falkland Islands.

Government[edit]

|

|---|

Executive authority in Saint Helena is vested in King Charles III and is exercised on his behalf by the Governor of Saint Helena. The Governor is appointed by the King on the advice of the British government. Defence and foreign affairs remain the responsibility of the United Kingdom.

The Executive Council is presided over by the Governor and consists of three ex officio officers and five elected members of the Legislative Council appointed by the Governor. There is no elected Chief Minister, and the Governor acts as the head of government. In January 2013 it was proposed that the Executive Council would be led by a Chief Councillor who would be elected by the members of the Legislative Council and would nominate the other members of the Executive Council. These proposals were put to a referendum on 23 March 2013, when they were defeated by 158 votes to 42 on a 10% turnout.[72] Another referendum in 2021, however, saw the population approve the changes.[73]

The legislature of Saint Helena consists of the unicameral Legislative Council of Saint Helena and the King-in-Parliament (represented by the Governor). The Legislative Council consists of 15 members, of whom 12 are directly elected members who each serve a four-year term; a Speaker and Deputy Speaker who are chosen by the elected members; and one ex officio member, the Attorney General. Members of the Council use the post-nominal letters "MLC" (Member of the Legislative Council)

The island is policed by the Royal Saint Helena Police Service (RSHPS). The RSHPS is also the primary law enforcement agency for Ascension Island and the archipelago of Tristan da Cunha. Like many other Commonwealth nations, the warranted personnel of the RSHPS are known as 'constables', and the service also uses special constables, in addition to employing non-warranted staff personnel. The RSHPS also uses a variety of ranks similar to other Commonwealth law enforcement agencies. Saint Helena has one police station, Coleman House, named after PC Leonard John Coleman who died in the line of duty on 2 December 1982.[74] The Island's only prison—HMP Jamestown—was built in 1827 and in 2018.

One commentator has observed that notwithstanding the high unemployment resulting from the loss of full passports during 1981–2002, the Saint Helena population's loyalty to the British monarchy is probably not exceeded in any other part of the world.[75] King George VI is the only reigning monarch to have visited the island. This was in 1947 when the King, accompanied by Queen Elizabeth (later The Queen Mother), Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II) and Princess Margaret were travelling to South Africa. The Duke of Edinburgh arrived at Saint Helena in 1957, followed by his son, Prince Andrew, who visited as a member of the armed forces in 1984, and his daughter, the Princess Royal, in 2002. Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh made an official visit to Saint Helena in late January 2024, where he was greeted by Jonathan the Tortoise, a 191 years-old Seychelles Giant Tortoise born during the reign of King William IV.

Human rights[edit]

In 2012, the government of Saint Helena funded the creation of the Saint Helena Human Rights Action Plan 2012–2015.[76] Work is being done under this action plan, including publishing awareness-raising articles in local newspapers, providing support for members of the public with human rights queries, and extending several UN Conventions on human rights to St. Helena.[77]

Legislation to set up an Equality and Human Rights Commission was passed by Legislative Council in July 2015. This commenced operation in October 2015.[78]

Child safeguarding inquiry 2015[edit]

In 2014, there were reports of child abuse in Saint Helena. Britain's Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) was accused of lying to the United Nations about child abuse in Saint Helena to cover up allegations.[79][80][81]

Sasha Wass QC and her team arrived on Saint Helena on 17 March 2015 to commence the Inquiry and departed on 1 April 2015.[82] Announcements were made in local newspapers in the week ending 13 March 2015.

A government report was published on 10 December 2015. It found that the accusations were grossly exaggerated, and the lurid headlines in the Daily Mail had come from information from two social workers, whom the report described as incompetent.[83][84][85]

Same-sex marriage[edit]

In 2017, a male St Helenian made an application to the Registrar to marry his male fiancé on St Helena.[86] The laws at the time had referred to marriages between men and women and it was not clear whether same-sex marriages were lawful. After consultation events, endorsement by the Social and Community Development Committee and Executive Council, the Marriage Ordinance was updated and agreed by Legislative Council in December 2017. Registrar Karen Yon oversaw the first same-sex wedding between the original 2017 applicants, Saint Helenian Lemarc Thomas and Swedish national Michael Wernstedt, in a ceremony at Plantation House on 31 December 2018.[87]

Reburial of excavated human remains[edit]

In 2021, a wreath was placed by the Saint Helena's Equality & Human Rights Commission (EHRC) on the door of the Pipe Store in Jamestown.[88] The Pipe Store is a building where the remains of some 325 people, men, women, and children disinterred during airport construction were being stored pending reburial since 2008. The remains belonged to liberated Africans who had been rescued by the Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron during the suppression of the Atlantic slave trade and brought to Saint Helena.[89][90]

Biodiversity[edit]

Saint Helena has long been known for its high proportion of endemic birds and vascular plants. The highland areas contain most of the 400 endemic species recognised to date. Much of the island has been identified by BirdLife International as being important for bird conservation, especially the endemic Saint Helena plover or wirebird, and for seabirds breeding on the offshore islets and stacks, in the north-east and the south-west Important Bird Areas.[91]

On the basis of these endemics and an exceptional range of habitats, Saint Helena is on the United Kingdom's tentative list for future UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[92] Artist Rolf Weijburg produced original etchings of Saint Helena, picturing various species of these endemic birds.[93]

Saint Helena's biodiversity, however, also includes marine vertebrates, invertebrates (freshwater, terrestrial and marine), fungi (including lichen-forming species), non-vascular plants, seaweeds and other biological groups. To date, very little is known about these, although more than 200 lichen-forming fungi have been recorded, including nine endemics,[94] suggesting that many significant discoveries remain to be made.

Various flora and fauna on the island have become extinct. Due to deforestation, the last wild endemic St Helena olive tree, Nesiota elliptica died in 1994, and by December 2003, the last cultivated olive tree died.[95] The native St.Helena earwig was last seen in the wild in 1967.

A large reforestation project has been under way since 2000 in the north-eastern corner of the island, known as the Millennium Forest, to recreate the Great Wood that existed before colonisation.[96]

The island's shoreline is deep and is known to have abundant red crab. In 1991, a crab-fishing vessel, Oman Sea One, which was engaged in potting of crabs, capsized and later sank off the coast of Saint Helena on its way from Ascension Island, losing four crew members. One crew member was rescued by RMS St Helena.

Economy[edit]

- Note: Some of the data in this section have been sourced from the Government of St Helena Sustainable Development Plan[97]

The island had a monocrop economy until 1966, based on the cultivation and processing of New Zealand flax for rope and string.

A 2019 report states that "by the 1970s, a majority of Saints were working abroad and sending money home".[37]

Saint Helena's economy is now developing, but is almost entirely sustained by aid from the British government. The public sector dominates the economy, accounting for about 50% of gross domestic product. However, the start of regular air services has led to a rise in tourism, and the Government is encouraging investment on the island, as shown by their Investment Policy and Strategy and the investment prospectus for potential investors.[98] In 2019, Saint Helena achieved its first-ever "Investment Grade" credit rating, a credit rating of BBB− (stable), from global credit rating agency Standard & Poors (S&P).[99]

In 2019, the estimated average annual salary was only about 8,000 Saint Helena pounds (about US$10,000).[37]

Saint Helena's Sustainable Economic Development Plan, 2018–28, was developed using more than six months of local and international consultation in 2017–2018. The document represented a 10-year plan to kick-start the economy after Saint Helena established air access and fibre connectivity and moved away from relying purely on tourism for growth, announcing a desire to "increase exports, and decrease imports". The SEDP stated that the island's comparative advantages are its natural resources and geography, its status as a British Overseas Territory, its currency, relatively inexpensive labour and property costs, and low crime. Targeted export growth sectors include tourism, fisheries, coffee, satellite ground stations, remote workers and digital nomads, academia, research and conferences, liquor, wines and beers, ship registry and sailing qualifications, traditional products, honey and honey bees, and its use as a film location. Growth sectors for import substitution include agriculture, timber, bricks, blocks, minerals and rocks, and bottled water.[97]

The tourist industry is heavily based on the promotion of Napoleon's imprisonment as well as nature activities such as scuba diving, swimming with whale sharks, whale watching, bird watching, marine tours, and hiking. There is also a golf course, and sportfishing is possible. Several hotels, B&Bs, and self-catering apartments operate on the island. The arrival of tourists is linked to the Saint Helena Airport (and in the past, the arrival and departure schedule of the now-retired RMS St Helena).[100]

Saint Helena produces the most expensive coffee in the world.[101] It also produces and exports Tungi Spirit, made from the fruit of the prickly or cactus pears, Opuntia ficus-indica ("Tungi" is the local Saint Helenian name for the plant), and coffee liqueur, gin, and rum in its local distillery.[102] Due to the absence of parasites and disease in bees, beekeepers collect some of the purest honey in the world.

Saint Helena has a small fishing industry, landing mostly tuna. The fishery is committed to one-by-one fishing[clarification needed] and uses the motto "one pole, one line, one fish at a time". Some of Saint Helena's exported tuna has been served in restaurants in Cape Town.[103]

Like Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha, Saint Helena is permitted to issue its own postage stamps, an enterprise that provides an income. Saint Helena also issues domain names under the top-level domain .sh.

Economic statistics[edit]

Between 2009 and 2017, Saint Helena's HDI increased from 0.714 to 0.756; this placed Saint Helena in the 'high' category of human development, according to the classification used by the United Nations. Compared to other countries around the globe, Saint Helena's HDI ranking rose from 93rd (out of 190 countries ranked) to 83rd in the world.[104]

The average (median) annual wage on Saint Helena in 2018–19 was an estimated £8,410. The median male wage was higher than the median female wage. The gap between the two grew in 2013–14, but narrowed in 2017–18, as male wages fell on average, and the median female wage level grew. This is probably due to the completion of the construction of the airport, since workers employed on the project were predominantly male, and many of them either left Saint Helena or found alternative employment between 2016 and 2018. Nonetheless, both female and male median wage levels fell sharply in 2018–19.[105]

The overall retail price index is measured quarterly on Saint Helena by the SHG Statistics Office. The RPI was measured at 105.9 in the first quarter of 2020. This was unchanged from the index for the fourth quarter of 2019, and an increase from 104.1 in the first quarter of 2019. This means that retail prices rose, on average, by 1.7% over the year between the first quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020. As most of the goods available in retail outlets on Saint Helena are imported from either South Africa or the United Kingdom, Saint Helena's prices are heavily influenced by price inflation in those two countries, the value of the Saint Helena pound compared to the South African rand, the cost of freight, and import taxes. In the UK, the annual price inflation rate (using the consumer price index) was 1.7% for February 2020, down from 1.8% in January 2020. In South Africa, the consumer price index was 4.6% for February, up from 4.5% in January 2020. In addition, since early 2019 the value of the South African Rand has steadily weakened, from around 17 Rand per pound to around 20 at the end of March 2020; this has a counter-effect to the South African inflation, and in some cases may even have made South African goods cheaper to buy. This will mitigate against some pressures which might cause prices to rise, such as increasing freight prices on the MV Helena.[106]

Between January 2010 and March 2016, just before the first 40 people arrived by air in April 2016, the average number of arrivals per month by sea (excluding day visitors arriving on cruise ships) was 307, with an average of 245 arriving on the Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Saint Helena. Between October 2017 (when the first scheduled air service began) and September 2019, an average of 432 passengers arrived per month, with 314 of those passengers arriving by air. Since October 2017, a total of 3,337 people have arrived by air in the first 12-month period, and 4,188 in the second. The increase in the second year followed the introduction of a mid-week flight during the peak period of December 2018 to April 2019. Arrivals by air were higher in the second year, in every month apart from May and June.[107]

Banking and currency[edit]

In 1821, Saul Solomon (the uncle of Saul Solomon) issued 70,560 copper tokens worth a halfpenny each Payable at St Helena by Solomon, Dickson and Taylor—presumably London partners—that circulated alongside the East India Company's local coinage until the Crown took over the island in 1836. The coin remains readily available to collectors.

Saint Helena has had its own currency since 1976, the Saint Helena pound, which is at parity with the pound sterling and is also the currency of Ascension Island. The government of Saint Helena produces its own coinage, banknotes since 1976 and circulating coins since 1984. Whereas circulating coins are struck with "Saint Helena • Ascension", the banknotes only say "Government of St. Helena". There are also commemorative coins struck for Saint Helena only.

The Bank of Saint Helena was established on Saint Helena and Ascension Island in 2004. It has branches in Jamestown on Saint Helena, and Georgetown, Ascension Island. The bank took over the business of the Saint Helena government savings bank and Ascension Island Savings Bank.[108]

For more information on currency in the wider region, see British currency in the South Atlantic and the Antarctic.

Tourism[edit]

Before the airport opened, the primary tourist groups were dedicated hikers and retirees, as the required voyage on the RMS St Helena took five days each way. That was unattractive to most tourists with regular jobs. The hikers seemed willing to use the extra days of leave to get to and from Saint Helena, and retirees would not be concerned with voyage times.[109]

The decision to build the airport, in order to significantly boost tourism, was taken in 2011 by the governments of Saint Helena and the UK. Construction was completed by 2016. One reason for the delay was that the British decided to fill in a valley "with some 800 million pounds of dirt and rock" to create flat land for the runway.[37]

The first flight did not arrive until October 2017, because of "dangerous wind conditions" that made landing large aircraft unsafe. The solution was to use smaller aircraft for the five- or six-hour flight[110] from South Africa. The wind still causes problems: "only a special, stripped-down Embraer 190 jet with the best pilots in the world can stick the landing". The government's long-term goal is to get 30,000 visitors per year. Because of the few flights, and limited capacity of the aircraft, however, only 894 visitors arrived in the year the airport finally opened.[37]

Passenger service on the Royal Mail ship was then discontinued.[111] The Airlink flights, operating twice a week,[112] increased the island's potential to attract a broader range of tourists.[113]

St Helena Tourism[114] updated its tourism marketing strategy in 2018. This outlined the targeted markets and Saint Helena's strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. It also outlined the unique selling points of the island, including nature (whale sharks and wirebirds), Saint culture (safer environment), walking and hiking, diving, arts and crafts, twin destination with South Africa, photography, running, history and heritage (Napoleon), stargazing, and food and drink.[115]

The island's first luxury hotel, the Mantis in Jamestown, opened in 2017 in the converted "former officers barracks built in 1774" according to Condé Nast Traveler.[110] Most other types of accommodations were also available on the island.[116]

A 2019 report by The Guardian recommended that tourists visit "Longwood House, where Napoleon was exiled after Waterloo ... Plantation House, the residence of the governor" and to try one of the whale shark snorkelling expeditions. The report spoke highly of Jamestown, with its "pastel-toned houses, sweltering palm trees and colonial relics—stark reminders of imperialist ideals".[117] Another 2019 report indicated that smartphones had become common, "with the 'Saint Memes' Facebook page and other social media exporting their sharp sense of humour". But, as the report concludes, the island "remains a place with an anchor in the past, where ... there are single-digit car licence plates and motorists on the hairpin roads unfailingly wave at each other".[39]

Before the lockdowns and restriction necessitated by the COVID-19 global pandemic, Saint Helena was on track to meet its tourism targets of 12% growth a year, in order to achieve over 29,000 leisure visitors by the 25th anniversary of the air service.[118]

As of April 2020, research indicated that arrivals in Saint Helena were primarily non-Saint tourists (without a connection to the island), followed by returning Saints (who were visiting friends and relatives), followed by returning residents and then business arrivals. Non-Saint tourists tend to stay for a week, whilst Saints visiting friends and relatives tend to stay for about a month. Around 37% of tourists are British, 21% South African, 13% European other than British, German or French and 9% American or from the Caribbean. Most non-Saint tourists are over 40 years of age, with around 40% being 40 to 59 and around 40% being 60-plus. In 2018 tourism contributed approximately £4–5 million to the economy, and in 2019 this increased to around £5–6 million.[119]

Effects of the pandemic[edit]

One news report in August 2020 stated that the costs imposed by the pandemic led to the "collapse of the island's tourism sector, which was meant to drive its economic development".[111]

In 2021, the bicentennial anniversary of Napoleon's death was expected to boost tourism if the pandemic did not prevent visits for many months. As of September 2020, the government was preparing a "tourism recovery strategy",[120] to include an international publicity campaign and the development of further tourism infrastructure for the island".[111]

As of 30 October 2020, the Government website stated that "due to the COVID-19 pandemic, travel to Saint Helena will only be permitted for limited purposes at this time".[121] An item posted on 4 March 2021 on the UK Government website stated that "all arrivals to St Helena are required to have had a negative COVID-19 test within 72 hours before travelling" and with a few exceptions, non-Saints were not allowed to visit. In addition, all arrivals were required to self-quarantine for 14 days after landing in Saint Helena.[122]

As of 8 August 2022, the Government website stated that "St Helena lifted its COVID-19 entry regulations. This means no quarantine, no testing and no mask-wearing requirements".[123]

Energy[edit]

Connect Saint Helena Ltd. operates electricity generation and distribution. As of 2023, 80% of electricity generated in St Helena comes from 6 diesel generators.[124] 12 wind turbines are installed on the Deadwood Plain in Longwood and were originally installed in the 1990s, expanded in 2009 and 2014. A 500kW solar farm is in operation as well as photovoltaic arrays on 4 public buildings. As a result of the fact that almost all energy must be imported (diesel/oil), electricity is expensive in St Helena, at £0.53/kWh as of 2024.[125] 42% of the utility's costs are due to oil purchases.[126]

A plan to expand the use of renewable solar and wind power was announced in 2016, but never came to fruition. Electricity production from wind has declined steadily from 2014-2024, due to unreliable equipment and grid balancing challenges. In 2024, a new target of 80% renewable electricity production by 2027 was announced, by renewing and expanding wind and solar facilities as well as considering the potential of battery storage.[127]

Transport[edit]

Saint Helena is one of the most remote islands in the world. It has one commercial airport, Saint Helena Airport; access to the island improved greatly since its opening in 2017. Sea freight is serviced through Saint Helena's single wharf in Ruperts. The island has a mostly paved road network extending to all inhabited areas of the island, although it is mostly single lane.[128]

Sea[edit]

The Saint Helena Government contracts international shipping companies to provide maritime freight services to the island. As of March 2024, MACS Maritime Carrier Shipping GmbH & Co provides regular freight services to the island, usually on a monthly basis. It sails from Cape Town to Saint Helena and Ascension Island.

Commercial shipping to Saint Helena's is handled at the island's sole wharf at Ruperts Bay, originally built to assist the airport construction.[129]

Until 2017, the Royal Mail Ship RMS St Helena ran between Saint Helena and Cape Town on a five-day voyage, then the only scheduled connection to the island. She berthed offshore in James Bay, Saint Helena about 30 times per year, and passengers and freight were transferred ashore by small boats.[130]

Saint Helena receives around 600 yachting visitors a year.[131]

Air[edit]

Saint Helena Airport (IATA: HLE) was opened for commercial traffic on 14 October 2017, the island's first and only airport. The South African airline Airlink operates weekly flights to Johannesburg, as well as charter flights to Ascension Island and seasonal flights to Cape Town. The airport also operates medivac flights and accommodates general aviation. Scheduled flights to and from Johannesburg operated by an Embraer E190 usually include a fuel stop at Walvis Bay, with a flight time of around 4.5 to 6 hours. Air freight (including mail) is carried by scheduled air services.[132]

The prospect of an airport on St Helena was debated for a long time. Eventually, in March 2005 the British government announced plans to construct the Saint Helena Airport. This aimed to help the island become more self-sufficient, encouraging economic development through tourism while reducing dependence on British government aid.[133][134] In 2011, South African civil engineering company Basil Read was contracted to construct the airport, originally projected to open in 2016.[135] The first aircraft landed at the new airport on 15 September 2015. The airport's opening date was delayed due to uncertainty about the impact of high winds and wind shear.[136] In 2017, South African airline Airlink became the preferred bidder to provide weekly air service between the island and Johannesburg.

Due to the location of the airport site, at times serious wind shear makes it difficult to land from the north. It is safe to land from the other direction, but it is plagued by tailwinds, which increases landing ground speed and can limit aircraft loading.[137]

Road[edit]

Traffic in Saint Helena drives on the left and road signs are based on British standards. There is an island-wide speed limit of 30 mph (~50 kmh); lower in some areas. There are many private vehicles on the island despite the steep and narrow roads, hairpin bends and limited parking in Jamestown.[138] Major roads into Jamestown include Side Path and Field Road, which have been upgraded and improved in the period 2022-2024. There are three roundabouts on the island. The road constructed for conveying materials from Ruperts Bay to the airport during construction was paved and opened for public traffic in 2019, a major addition to the island's road network.[139]

A minibus offers a basic bus service to carry people around Saint Helena, with most services designed to take people into Jamestown. Taxis as well as car hire services are available.[140]

Media and communications[edit]

Telecommunications services in St Helena are provided by Sure South Atlantic, providing landline, mobile (2G/4G), internet and television services. International connectivity is provided by the Google Equiano submarine cable.[141] There are three FM radio stations broadcasting in St Helena as of 2023 and two weekly newspapers are published.

All of St Helena's international connectivity was by satellite until the activation of the Equiano submarine cable in October 2023.[142]

Telecom services in St Helena are comparatively expensive, for example, all TV channels are encrypted and a subscription costs amount to more than one tenth of an average worker's salary.[143][144]

Sure South Atlantic holds a licensed monopoly on telecommunications on the island until 31 December 2025. As of 2023, new telecoms regulations were being drafted; there was a "possibility of issuing a license to a different provider after Sure's term expires".[145]

Telecommunications[edit]

Saint Helena has the international calling code +290, which Tristan da Cunha has shared since 2006. Landline telephones are available to all households on the island. Until 2023, a satellite ground station with a 7.6-metre satellite dish installed in 1989 was the only international connectivity to the island. Bandwidth was extremely limited and data caps were low.

The Equiano submarine cable was activated in 2023, substantially improving communications on the island, offering hugely increased bandwidth and unlimited data plans for the first time.[146]

Mobile phone service (2G/4G) commenced in September 2015.[38] As of 2024, ADSL2 service is available to most households, with speeds ranging from 2 to 20 Mbit/s. It is envisioned that a fibre optic network will be installed to homes and businesses by Maestro Technologies, but plans have stalled as of 2024.[147]

Television and Radio[edit]

Television services first arrived in 1995. The current digital broadcasting network uses DVB-T2 standards and retransmits international content from satellites.[148] A local television channel was in operation from 2015 to 2017 by SAMS, consisting of a weekly news bulletin.[149]

Radio broadcasting began in 1967 with Radio Saint Helena (now defunct). Today, South Atlantic Media Services (SAMS), supported by the St Helena Government, broadcasts two FM stations: SAMS Radio 1, providing locally produced news, talk and music programming; SAMS also rebroadcasts the BBC World Service.[150][151] Saint FM Community Radio is the island's only independent broadcaster. [152][153]

Occasional amateur radio operations also occur on the island. The ITU prefix used is ZD7.[154]

Local newspapers[edit]

The island has two local newspapers, both of which are available online.[155] The St Helena Independent[156] has been published since November 2005. The Sentinel newspaper was introduced in 2012.[157] Saint Helena Island Info is an online resource featuring the history of St. Helena from its discovery to the present day, plus photographs and information about life on St. Helena today.[158]

Satellite ground stations[edit]

In February 2018, the government of St Helena launched a project to attract low earth orbit satellite operators to install ground stations on the island. Leasing backhaul capacity could contribute to operational costs on the submarine cable. OneWeb announced the construction of a satellite ground station on St. Helena in 2023.[159][160]

Culture and society[edit]

Education[edit]

The Education and Employment Directorate, formerly the Saint Helena Education Department, in 2000 had its head office in The Canister in Jamestown.[161] Education is free and compulsory between the ages of five and 16.[162] At the beginning of the academic year 2009–10, 230 students were enrolled in primary school and 286 in secondary school.[163] The island has three primary schools for students of age four to 11: Harford, Pilling, and St Paul's.

- St Paul's Primary School in St Paul's,[164] formerly St Paul's Middle School, has both first and middle levels as it was formed by a 1 August 2000 merger.[165] As of 2020[update] it has 134 students and serves, in addition to St Paul's, Bluehill, Gordons Post, New Ground, Sandy Bay, and Upper Half Tree Hollow.[164] In 2002, in addition to St Paul's it served a portion of Half Tree Hollow as well as the communities of Blue Hill, Guinea Grass, Hunt's Bank, New Ground, Sandy Bay, Thompson's Hill, and Vaughn's.[165]

- Harford Primary School in Longwood, with Governor James Harford as its namesake,[164] opened as a senior school in 1957 and became Hardford Middle School in September 1988.[166] It merged with Longwood First School in 2008. It also serves Alarm Forest and Levelwood.[164]

- Pilling Primary School is in Jamestown.[167] Occupying a former garrison, the school was established in 1941 and became Pilling Middle School in 1988.[168] Jamestown First School, located next door to Pilling Middle, merged into it in May 2005 as a result of declining enrolment. The merged school initially used both buildings, but as the enrolment continued its decline, the ex-Jamestown First Building, constructed in 1959, was no longer in use after 2007. In addition to Jamestown it serves Alarm Forest, Briars, Lower Half Tree Hollow, Rupert's, and Sea View. As of 2020[update] it had 126 students.[167]

Prince Andrew School provides secondary education for students aged 11 to 18.

It formerly had separate first schools catering to younger students (ages 3 to 7 as of 2002):

- Half Tree Hollow First School, originally a primary school, opened as such in 1949 with its current name and year configuration in place since 1988. In addition to Half Tree Hollow it served Cleugh's Plain, New Ground, and Sapper Way.[169]

- Jamestown First School, originally Jamestown Junior School, opened as such in 1959 with its current name and year configuration in place since 1988.[170]

- Longwood First School, originally a primary school, opened in 1949 in a former mess hall for military officers that had been constructed in 1942; this building had an expansion in 1977, and there are four classrooms in a separate building that was built in 1958. Longwood became a "first school" in 1988.[171]

The Education and Employment Directorate also offers programmes for students with special needs, vocational training, adult education, evening classes, and distance learning. The island has a public library (the oldest in the Southern Hemisphere,[172] open since 1813[173]) and a mobile library service which operates weekly in rural areas.[174]

The English national curriculum is adapted for local use.[174] A range of qualifications are offered—from GCSE, A/S and A2, to Level 3 Diplomas and Vocationally Recognised Qualifications (VRQs):[175]

- GCSEs

- Design and Technology

- ICT

- Business Studies

- A/S & A2 and Level 3 Diploma

- Business Studies

- English

- English Literature

- Geography

- ICT

- Psychology

- Maths

- Accountancy

- VRQ

- Building and Construction

- Automotive Studies

Saint Helena has no tertiary education. Scholarships are offered for students to study abroad.[174] St Helena Community College (SHCC) has some vocational and professional education programmes available.[176]

Sport[edit]

Historically, the St Helena Turf Club organised the island's first recorded sports events in 1818 with a series of horse races at Deadwood.[177] Saint Helena has sent teams to a number of Commonwealth Games. Saint Helena is a member of the International Island Games Association.[178] The Saint Helena cricket team made its debut in international cricket in Division Three of the African region of the World Cricket League in 2012. The Saint Helena football team first tournament was the 2019 Inter Games Football Tournament after which it was ranked tenth out of ten.

The Governor's Cup is a yacht race between Cape Town and Saint Helena island, held every two years in December and January.

In Jamestown a timed run takes place up Jacob's Ladder every year, with people coming from all over the world to take part.[179]

Scouting and Girl Guiding[edit]

There are Scouting and Guiding Groups on Saint Helena and Ascension Island. Scouting was established on Saint Helena island in 1912.[180] Lord and Lady Baden-Powell visited the Scouts on Saint Helena on the return from their 1937 tour of Africa. The visit is described in Lord Baden-Powell's book, titled African Adventures.[181]

Cuisine[edit]

In 2017, Julia Buckley of The Independent wrote that, due to the lack of nouvelle cuisine, the food is "[p]retty retro, at least by London standards."[113] Fish cakes in a St Helena style, with egg binding and chili, and a risotto-with-curry dish called pilau (or plo, similar to the Indian rice dish pulao) are what Buckley describes as "staple[s]".[113] Indeed, most of the local recipes are variations of world dishes brought to the island by travellers.[182]

Language[edit]

English is the official language.[183] The local basilect is called Saint-speak, Saint, or Saint English, which is a form of South Atlantic English.[184][185][186]

Notable people[edit]

- Fernão Lopes (died 1545), Portuguese soldier, first-known permanent inhabitant of the island

- John Doveton (1768 St Helena – 1847), East India Company military officer

- Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821 St Helena), French Emperor, exiled 1815–1821, died on the island[187]

- Daniel Richard Caldwell (1816 St Helena – 1875), colonial official.[188]

- Saul Solomon (1817 St Helena – 1892), liberal politician of the British Cape Colony

- François d'Orléans, Prince of Joinville (1818–1900), brought the remains of Napoleon to France

- William Bailey (1851 St Helena – 1896), trade unionist in GB and Primitive Methodist preacher

- Dinuzulu (c. 1868–1913), Zulu king exiled in St Helena from 1890–1897

- Khalid bin Bargash (1874–1927), deposed Sultan of Zanzibar, exiled in St Helena in 1917

- Michel Dancoisne-Martineau (born 1965), director of the French domains of Saint Helena

- Belinda Bennett (born c. 1977 St Helena), cruise ship captain from Saint Helena

- Julie Thomas (born c. 1980 St Helena), inaugural Chief Minister of Saint Helena

Notable creature[edit]

- Jonathan (hatched c. 1832), Seychelles giant tortoise brought to Saint Helena in 1882, is the world's oldest-known living land animal. He celebrated his 190th birthday in 2022.[189][190]

Namesake[edit]

St Helena, a suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, was named after the island.

See also[edit]

- Lists of islands

- Wildlife of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

- Manatee of Helena

- Outline of Saint Helena

- Saint Helena Police Service

- Healthcare in Saint Helena

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b The St Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha Constitution Order 2009 Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine "...the transfer of rule of the island to His Majesty's Government on 22 April 1834 under the Government of India Act 1833, now called the Saint Helena Act 1833" (Schedule Preamble)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "St-Helena at a Glance" (PDF). St Helena Government. 18 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). "St Helena". Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ "Saint Helena". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ "Constitution of St. Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha". UK Archives. 2009. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ Bruce, Ian. 'The Discovery of St Helena'. Wirebird: The Journal of the Friends of St Helena 51 (2022): 26–43. [1]

- ^ Cardozo, Manoel (1963). "The Idea of History in the Portuguese Chroniclers of the Age of Discovery". The Catholic Historical Review. 49 (1): 1–19. JSTOR 25017190.

- ^ João de Barros, Manoel Severim de Faria, and João Baptista Lavanha, Da Asia de João de Barros e de Diogo de Couto, vol. I, book V, chapter X (Lisbon: Regia Officina Typografica, 1778), 477; [2]

- ^ Luiz de Figueiredo Falcão, Livro em que se contém toda a fazenda e real patrimonio dos reinos de Portugal, India, e ilhas adjacentes e outras particularidades (Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional, 1859), 138; [3]

- ^ Damião de Góis, Chronica do serenissimo senhor rei D. Manoel (Lisbon: Na officina de M. Manescal da Costa, 1749), 85; [4]

- ^ Barros, Faria, and Lavanha, Da Asia de João de Barro, I, book V, chapter X:118; [5]

- ^ Manuel de Faria e Sousa, Asia Portuguesa, vol. 1 (En La Officina de Henrique Valente de Oliueira, 1666), 50; [6]

- ^ Melchior Estacio Do Amaral, Tratado das batalhas e sucessos do Galeão Sanctiago com os Olandeses na Ilha de Sancta Elena: e da náo Chagas com os Vngleses antre as Ilhas dos Açores, 1604, 20; [7]

- ^ Barros, Faria, and Lavanha, Da Asia de João de Barro, I, book V, chapter X:477; Góis, Chronica do serenis-simo, 477

- ^ Marino Sanuto, I Diarii di Marino Sanuto, ed. Nicolò Barozzi, vol. 4 (Venice: F. Visentini, 1880), 486 [8]

- ^ Guglielmo Berchet, Fonti italiane per la storia della scoperta del Nuovo mondo, vol. 1, part III (Rome: Ministero della pubblica istruzione, 1892), 152 [9]

- ^ Duarte Leite, História da colonização portuguesa do Brasil, Chapter IX, O mais antigo mapa do Brasil, ed. Carlos Malheiro Dias, vol. 2 (Porto: Litografia Nacional, 1922), 251, [10]

- ^ Harold Livermore, 'Santa Helena, A Forgotten Portuguese Discovery, Estudos Em HOmenagem a Louis Antonio de Oliveira Ramos, 2004, 623–31, [11]

- ^ Jean Philibert Berjeau, trans., Calcoen. A Dutch Narrative of the Second Voyage of Vasco Da Gama to Calicut, Printed at Antwerp circa 1504 (London: Basil Montague Pickering, 1874), 37, [12]

- ^ George E. Nunn, The Mappemonde of Juan de La Cosa: A Critical Investigation of Its Date (Jenkintown: George H. Beans library, 1934

- ^ Edzer Roukema, 'Brazil in the Cantino Map', Imago Mundi 17 (1963): 15.

- ^ "May 21: Feast of the Holy Great Sovereigns Constantine and Helen, Equal to the Apostles". Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. Archived from the original on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ^ Ian Bruce, 'St Helena Day', Wirebird The Journal of the Friends of St Helena, no. 44 (2015): 32–46.[13] Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, Itinerario, voyage ofte schipvaert van Jan Huygen Van Linschoten naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien, inhoudende een corte beschryvinghe der selver landen ende zee-custen... waer by ghevoecht zijn niet alleen die conterfeytsels van de habyten, drachten ende wesen, so van de Portugesen aldaer residerende als van de ingeboornen Indianen. (C. Claesz, 1596)[14].

- ^ Jan Huygen van Linschoten, John Huighen Van Linschoten, His Discours of Voyages into Ye Easte [and] West Indies: Divided into Foure Bookes (London: John Wolfe, 1598).[15]

- ^ Duarte Lopes and Filippo Pigafetta, Relatione del Reame di Congo et delle circonvicine contrade tratta dalli scritti & ragionamenti di Odoardo Lope[S] Portoghese / per Filipo Pigafetta con disegni vari di geografiadi pianti, d'habiti d'animali, & altro. (Rome: BGrassi, 1591).[16]

- ^ Thomas Herbert, Some Yeares Travels into Africa et Asia the Great: Especially Describing the Famous Empires of Persia and Industant as Also Divers Other Kingdoms in the Orientall Indies and I'les Adjacent (Jacob Blome & Richard Bishop, 1638), 353.

- ^ Linschoten, Jan Huygen van; Burnell, Arthur Coke; Tiele, Pieter Anton (1885). The voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies : from the old English translation of 1598 : the first book, containing his description of the East. London: Hakluyt Society – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Disney, A.R. (2016). The Portuguese in India and other studies, 1500–1700 (Ch. XVII – The Portuguese and Saint Helena). Routledge. pp. 217–219. ISBN 978-1-138-49378-0.

- ^ Rowlands, Beau W. (Spring 2004). "Ships at St Helena, 1502-1613" (PDF). Wirebird: The Journal of the Friends of St Helena (28): 5–10.

- ^ Schulenburg, Alexander H. (Autumn 1997). "Joao Da Nova and the Lost Carrack" (PDF). Wirebird: The Journal of the Friends of St Helena (16): 19–23.

- ^ Knowlson, James R. (1968). "A Note on Bishop Godwin's "Man in the Moone:" The East Indies Trade Route and a 'Language' of Musical Notes". Modern Philology. 65 (4): 357–91. doi:10.1086/390001. JSTOR 435786. S2CID 161387367.

- ^ Drake and St Helena, privately published by Robin Castell in 2005

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g E. A. B., E. A. (July 1940). "Review". The English Historical Review. 55 (219). Oxford University Press: 494. JSTOR 554169.

- ^ "Historical Chronology". St. Helena Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ Schulenburg, Alexander (1999). "Myths of Settlement – St Helena and the Great Fire of London" (PDF). Friends of St Helena. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k "A Journey to St. Helena, Home of Napoleon's Last Days". Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "A Brief History". Saint Helena Island. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "A Visit to St Helena, One of the World's Remotest Islands". 18 December 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Gazetteer – p. 7. Monuments in France – page 338 Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Beaglehole, J.C., ed. (1968). The Journals of Captain James Cook on His Voyages of Discovery, vol. I:The Voyage of the Endeavour 1768–1771. Cambridge University Press. p. 468. OCLC 223185477.

- ^ "SLAVERY ON ST HELENA". sainthelenaisland.info.

- ^ PBS POV S36 Ep2 "The Story of Bones" 2023

- ^ "Napoleon on St Helena: how exile became the French emperor's last battle". HistoryExtra. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Andrew (2014). Napoleon : A Life. New York: Viking. pp. 778, 781–82, 784, 801. ISBN 978-0-670-02532-9.

- ^ "Friends of St Helena". Archived from the original on 6 May 2013.

the island became a temporary refuge for more than 26,000 Africans liberated by the Royal Navy from slave ships.

[unreliable source?] - ^ Jump up to: a b Richard Grove, Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 309–379

- ^ Geoffrey Wolff, The Hard Way Around: The Passages of Joshua Slocum, p 11

- ^ Royle, Stephen A. 'Alexander The Rat – F. W. Alexander, Chief Censor, Deadwood Camp, St Helena'. Wirebird: The Journal of the Friends of St Helena 15 (Spring 1997): 17–21.Full Paper

- ^ Knight, Ian (2004). Boer Commando 1876–1902. Osprey Publishing. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-84176-648-5.

- ^ Clements, Bill. 'Second World War Defences on St Helena'. Wirebird: The Journal of the Friends of St Helena 33 (Autumn 2006): 11–15. Full Paper

- ^ "Enhanced status and Bill of Rights in Tristan's new constitution". Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "The St Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha Constitution (Amendment) Order 2021". www.legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ "The New Ministerial System". St Helena Government. 18 August 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Natural History of Saint Helena Archived 13 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bird Watching, St Helena Tourism, archived from the original on 17 September 2010, retrieved 17 January 2011

- ^ Our Flag, Moonbeams Limited, archived from the original on 15 October 2014, retrieved 11 November 2014

- ^ Jump up to: a b "St. Helena, Ascension, and Tristan da Cunha", CIA World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, retrieved 21 July 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b About St Helena, St Helena News Media Services Archived 20 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "BBC Weather Centre". Archived from the original on 9 February 2011.

- ^ St Helena Independent, 3 October 2008 page 2

- ^ "Constitution". St Helena. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ "Census 2016– Summary Data". St Helena Government. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "2008 Population Census of St Helena" (PDF). St Helena Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b St Helena 2016 Population & Housing Census (PDF). Jamestown, St Helena: St Helena Statistics Office. 6 June 2016. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "St Helena 2021 Population & Housing Census" (PDF).

- ^ "Statistics Update: Population, Ascension Population, Production, Benefits and Exchange Rates « St Helena". 26 November 2018.

- ^ St Helena celebrates the restoration of full citizenship Archived 10 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Telegraph, 22 May 2002

- ^ Angelini, Daniel (24 August 2018). "St Helena expats from 'Swindolena' to gather for sports day this weekend". Swindon Advertiser. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Hearl, Trevor W. 'St Helena's Early Baptists'. Wirebird: The Journal of the Friends of St Helena 12 (Autumn 1995): 40–46.Full Paper

- ^ 2023 Service Year Report of Jehovah's Witnesses

- ^ "Constitutional Poll – Restults". The Islander. 25 March 2013. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ^ "Consultative Poll on Governance Reform – The Results". St Helena Government. 18 March 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2021..

- ^ "Service of Remembrance – Police Constable Leonard Coleman". St Helena Government. 28 November 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Smallman, David L., Quincentenary, a Story of St Helena, 1502–2002; Jackson, E. L. St Helena: The Historic Island, Ward, Lock & Co, London, 1903

- ^ "humanrightssthelena.org" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ "The Equality & Human Rights Commission • Introduction". humanrightssthelena.org. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ "The Equality & Human Rights Commission • Introduction". humanrightssthelena.org. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ "St Helena child abuse: Foreign Office 'was warned British island couldn't cope 12 years ago'". Telegraph. 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "St Helena child abuse: 'a lot of dark things do happen on this island'". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "St Helena child abuse: how did sex abusers get away with it for so long?". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "The St Helena Independent – Saint FM". Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "HC 662 The Wass Inquiry Report" (PDF). 10 December 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.