Clement Vallandigham

Clement Vallandigham | |

|---|---|

Vallandigham, photographed at some point during his Congressional career (1858-1863) | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 3rd district | |

| In office May 25, 1858 – March 3, 1863 | |

| Preceded by | Lewis D. Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Robert C. Schenck |

| Member of the Ohio House of Representatives from the Columbiana County district | |

| In office December 1, 1845 – December 5, 1847 Serving with Joseph F. Williams | |

| Preceded by | Robert Filson |

| Succeeded by | James Patton Joseph F. Williams |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Clement Laird Vallandigham July 29, 1820 New Lisbon, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | June 17, 1871 (aged 50) Lebanon, Ohio, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Accidental death by gunshot wound |

| Resting place | Woodland Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Louisa Anna Vallandigham |

| Alma mater | Jefferson College |

| Signature | |

Clement Laird Vallandigham (/vəˈlændɪɡəm/ və-LAN-dig-əm;[1] July 29, 1820 – June 17, 1871) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the leader of the Copperhead faction of anti-war Democrats during the American Civil War.

He served two terms for Ohio's 3rd congressional district in the United States House of Representatives. In 1863, he was convicted by an Army court martial for publicly expressing opposition to the war and exiled to the Confederate States of America. He ran for governor of Ohio in 1863 from exile in Canada, but was defeated.

Vallandigham died in 1871 in Lebanon, Ohio, after accidentally shooting himself in the abdomen with a pistol, while representing a defendant in a murder case for killing a man in a barroom brawl in Hamilton.

Early life

[edit]Clement Laird Vallandigham was born July 29, 1820, in New Lisbon, Ohio (now Lisbon, Ohio), to Clement and Rebecca Laird Vallandigham.[2] His father, a Presbyterian minister, educated his son at home.[3]

In 1841, Vallandigham had a dispute with the college president at Jefferson College in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. He was honorably dismissed, but he never received a degree.[4]

Edwin M. Stanton, the future Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln, was Vallandigham's close friend before the Civil War. Stanton lent Vallandigham $500 for a law course and to begin his own practice.[5] Both Vallandigham and Stanton were Democrats, but they held opposing views on slavery. Stanton was an abolitionist; Vallandigham an anti-abolitionist.

Political career

[edit]Ohio legislature

[edit]Shortly after beginning to practice law in Dayton, Ohio, Vallandigham entered politics. He was elected as a Democrat to the Ohio legislature in 1845 and 1846, and served as editor of a weekly newspaper, the Dayton Empire, from 1847 to 1849.

While in the Ohio state legislature, Vallandigham voted against the repeal of the "Black Laws" (laws against the civil rights of African-Americans) though he wanted the question put to a referendum by the voters.[6] In 1851, Vallandigham sought the Democratic nomination to be Ohio's lieutenant governor, but the party declined to nominate him.[3]

House of Representatives

[edit]Vallandigham ran for Congress in 1856, but he was narrowly defeated. He appealed to the Committee of Elections of the House of Representatives and claimed that illegal votes had been cast. The House eventually agreed, and Vallandigham was seated on the next to last day of the term. The delay was caused by "the division which had arisen in the Democratic party upon the Lecompton [slavery in Kansas] question."[7] He was reelected by a small margin in 1858.

In October 1859, a radical abolitionist, John Brown, raided Harper's Ferry, Virginia, seizing the United States Army Arsenal. Vallandigham happened to be passing through the town[8] and joined a group of government officials who interrogated the captured Brown as to his aims, which Brown stated were an attempt to set off a rebellion of slaves to secure their freedom.[9] Vallandingham commented on Brown:

Here was folly and madness. He believed and acted upon the faith which for twenty years has been so persistently taught in every form throughout the Free States, and which is but another mode of the statement of the doctrine of the 'irrepressible conflict'—that slavery and the three hundred and seventy thousand slaveholders of the South are only tolerated, and that the millions of slaves and non-slaveholding white men are ready and willing to rise against the 'oligarchy', needing only a leader and deliverer. The conspiracy was the natural and necessary consequence or the doctrine proclaimed every day, year in and year out, by the apostles of Abolition. But Brown was sincere, earnest, practical; he proposed no mild works in his faith, reckless of murder, treason, and every other crime. This was his madness and folly. He perished justly and miserably—an insurgent and a felon; but guiltier than he, and with his blood upon their heads, are the false and cowardly prophets and teachers of Abolition.[10]

Vallandingham was pro-slavery, described in a hostile newspaper as "perform[ing] the dirty work of the Southern slavocracy".[10] He was always a vigorous supporter of those "states' rights".[11] He believed the federal government had no power to regulate any legal institution, which slavery at the time was. He also believed the states had an implied right to secede and that, legally, the Confederacy could not militarily be conquered. Vallandigham was a believer in low tariffs and that slavery was a matter for each state to decide. During the ensuing war, he would become one of Lincoln's most outspoken critics.[3][12]

He was re-elected to the House in 1860. During the 1860 presidential campaign, he supported Stephen A. Douglas, although he disagreed with Douglas's position on "squatter sovereignty", which was used by detractors to describe popular sovereignty.[13]

On February 20, 1861, Vallandigham delivered a speech, titled "The Great American Revolution," to the House of Representatives. He accused the Republican Party of being "belligerent" and advocated a "choice of peaceable disunion upon the one hand, or Union through adjustment and conciliation upon the other." Vallandigham supported the Crittenden Compromise, which was a last-minute effort to avert the Civil War. He blamed sectionalism and anti-slavery sentiment for the secession crisis. Vallandigham proposed a series of amendments to the Constitution. The United States would be divided into four sections: North, South, West, and Pacific. The four sections would each have the power in the Senate to veto legislation. The Electoral College would be modified, with the term of president and vice-president increased to six years and limited to one term unless two thirds of the electors agreed. Secession by a state could be agreed to only if the legislatures of the sections approved it. Moving between the sections was a guaranteed right.[14]

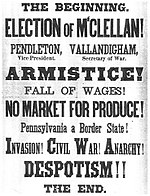

Vallandigham strongly opposed every military bill, which led his opponents to charge that he wanted the Confederacy to win the war. He became the acknowledged leader of the anti-war Copperheads, and in an address on May 8, 1862, he coined their slogan: "To maintain the Constitution as it is, and to restore the Union as it was." It was endorsed by fifteen Democratic congressmen.[15]

Vallandigham lost his bid for a third full term in 1862 by a relatively large vote, which meant that he would be out of office early in 1863. However, his loss was at least partially caused by the redistricting of his congressional district.[16] Despite this loss, some still considered him to be a future presidential candidate.[17]

As a lame-duck Representative, Vallandigham delivered a speech in the House on January 14, 1863, entitled "The Constitution-Peace-Reunion." In it, he stated his opposition to abolitionism from the "beginning." He denounced Lincoln's violations of civil liberties, "which have made this country one of the worst despotisms on earth". Vallandigham openly criticized Lincoln's preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, charging that "war for the Union was abandoned; war for the Negro openly begun." He also condemned financial interests that were profiting from the war: "And let not Wall Street, or any other great interest, mercantile, manufacturing, or commercial, imagine that it shall have power enough or wealth enough to stand in the way of reunion through peace." Vallandigham added, "Defeat, debt, taxation, sepulchers, these are your trophies." Vallandigham's speech included a proposal to end the military conflict. He advocated an armistice and the demobilization of the military forces of both the Union and the Confederacy.[18]

Post-congressional activities

[edit]

After General Ambrose E. Burnside issued General Order Number 38, warning that the "habit of declaring sympathies for the enemy" would not be tolerated in the Military District of Ohio, Vallandigham gave a major speech on May 1, 1863. He charged that the war was no longer being fought to save the Union, but it had become an attempt to free the slaves by sacrificing the liberty of white Americans to "King Lincoln."[19]

The authority for Burnside's order came from a proclamation of September 24, 1862 in which President Lincoln suspended habeas corpus and made discouraging enlistments, drafts, or any other "disloyal" practices subject to martial law and trial by military commissions.[20]

Arrest and military trial

[edit]On May 5, 1863, Vallandigham was arrested as a violator of General Order Number 38. His enraged supporters burned the offices of the Dayton Journal, the Republican rival to the Empire. Vallandigham was tried by a military court on May 6 and 7. Vallandigham's speech at Mount Vernon, Ohio, was cited as the source of the arrest. He was charged by the Military Commission with "Publicly expressing, in violation of General Orders No. 38, from Head-quarters Department of the Ohio, sympathy for those in arms against the Government of the United States, and declaring disloyal sentiments and opinions, with the object and purpose of weakening the power of the Government in its efforts to suppress an unlawful rebellion."[21]

The specifications of the charge against Vallandigham were:

Declaring the present war "a wicked, cruel, and unnecessary war"; "a war not being waged for the preservation of the Union"; "a war for the purpose of crushing out liberty and erecting a despotism"; "a war for the freedom of the blacks and the enslavement of the whites"; stating "that if the Administration had so wished, the war could have been honorably terminated months ago"; that "peace might have been honorably obtained by listening to the proposed intermediation of France"; that "propositions by which the Northern States could be won back, and the South guaranteed their rights under the Constitution, had been rejected the day before the late battle of Fredericksburg, by Lincoln and his minions", meaning thereby the President of the United States, and those under him in authority; charging "that the Government of the United States was about to appoint military marshals in every district, to restrain the people of their liberties, to deprive them of their rights and privileges"; characterizing General Orders No. 38, from Headquarters Department of the Ohio, as "a base usurpation of arbitrary authority", inviting his hearers to resist the same, by saying, "the sooner the people inform the minions of usurped power that they will not submit to such restrictions upon their liberties, the better"; declaring "that he was at all times, and upon all occasions, resolved to do what he could to defeat the attempts now being made to build up a monarchy upon the ruins of our free government"; asserting "that he firmly believed, as he said six months ago, that the men in power are attempting to establish a despotism in this country, more cruel and more oppressive than ever existed before."

Vallandingham wrote that he knew his public opinions and sentiments aided the Confederate war effort, raised public skepticism against the Lincoln administration, raised sympathy for the Confederate soldiers, and encouraged Northerners to violate the wartime laws of the Union.[22]

The peace proposal of France was true. Vallandigham had been requested by Horace Greeley to assist in the peace plan.[23]

Captain James Madison Cutts served as the judge advocate in the military trial and was responsible for authoring the charges against Vallandigham.[24] During the trial, testimony was given by Union army officers who had attended the speech in civilian clothes, that Vallandigham called the president "King Lincoln."[25] He was sentenced to confinement in a military prison "during the continuance of the war" at Fort Warren, Massachusetts.[26] Vallandingham only called one witness in his defense, Congressman Samuel S. Cox. According to University of New Mexico School of Law Professor Joshua E. Kastenberg, because Cox was another well-known anti-war Democrat, his presence at the military court likely harmed Vallandigam's attempts at arguing his innocence.[27]

On May 11, 1863, an application for a writ of habeas corpus was filed in federal court for Vallandigham by former Ohio Senator George E. Pugh.[28] Judge Humphrey H. Leavitt of the Circuit Court of the United States for the Southern District of Ohio upheld Vallandigham's arrest and military trial as a valid exercise of the President's war powers.[29] Congress had passed an act authorizing the president to suspend habeas corpus on March 3, 1863.[30]

On May 16, 1863, there was a meeting at Albany, New York, to protest the arrest of Vallandigham. A letter from Governor Horatio Seymour of New York was read to the crowd. Seymour charged that "military despotism" had been established. Resolutions by John V. L. Pruyn were adopted.[31] The resolutions were sent to Lincoln by Erastus Corning. In response to a public letter issued at the meeting of angry Democrats in Albany, Lincoln's "Letter to Erastus Corning et al." of June 12, 1863, explained his justification for supporting the court-martial's conviction.

In February 1864, the Supreme Court ruled that it had no power to issue a writ of habeas corpus to a military commission (Ex parte Vallandigham, 1 Wallace, 243).

Expulsion

[edit]

Lincoln, who considered Vallandigham a "wily agitator," was wary of making him a martyr to the Copperhead cause, and on May 19, 1863, he ordered Vallandigham to be sent through the enemy lines to the Confederacy.[11][32] When he was within Confederate lines, Vallandigham said: "I am a citizen of Ohio, and of the United States. I am here within your lines by force, and against my will. I therefore surrender myself to you as a prisoner of war."[33]

On May 30, 1863, a meeting was held at Military Park in Newark, New Jersey, where a letter was read from New Jersey Governor Joel Parker that condemned the arrest, trial, and deportation of Vallandigham as "were arbitrary and illegal acts. The whole proceeding was wrong in principle and dangerous in its tendency." However, the meeting was sparsely attended.[34] The New York World reported on the meeting in Albany. Burnside suppressed publication of the World.[35] On June 1, 1863, another protest meeting was held in Philadelphia.[36]

On June 2, 1863, Vallandigham was sent to Wilmington, North Carolina, by Confederate President Jefferson Davis and was briefly put under guard as an "alien enemy."[37]

President Lincoln wrote the "Birchard Letter" of June 29, 1863 to several Ohio congressmen; it offered to revoke Vallandigham's deportation order if they would agree to support certain policies of the Administration.

Vallandigham travelled to Richmond, Virginia, where he met with Robert Ould, a former classmate. He advised Ould that the Confederate army should not invade Pennsylvania since it would unite the North against the Copperheads during the 1864 presidential election.[38] However, a letter to the editor of The New York Times gave a different version that Vallandigham had encouraged the invasion.[39]

Vallandigham then left the Confederacy on a blockade runner to Bermuda and from there went to Canada.[40] He then declared himself a candidate for Governor of Ohio and actually won the Democratic nomination in absentia. (Outraged at his treatment by Lincoln, Ohio Democrats by a vote of 411–11 nominated Vallandigham for governor[41] at their June 11 convention.) He managed his campaign from a hotel in Windsor, where he received a steady stream of visitors and supporters.[42]

Vallandigham asked the question in his address or letter of July 15, 1863, "To the Democracy of Ohio:" "Shall there be free speech, a free press, peaceable assemblages of the people, and a free ballot any longer in Ohio?"[43]

Vallandigham lost the 1863 Ohio gubernatorial election in a landslide to the pro-Union War Democrat John Brough by a vote of 288,374 to 187,492.[44]

The Northwestern Confederacy

[edit]In Canada, sometime around March 1864, Vallandigham became a leader of the Order of the Sons of Liberty[45] and conspired with Jacob Thompson, and other agents of the Confederate government to form a Northwestern Confederacy, consisting of the states of Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois, by overthrowing their governments. Vallandigham requested money for weapons from the Confederates and refused to handle the money himself, which was given to his associate James A. Barrett. Part of the Confederate plan was to liberate Confederate prisoners-of-war.[46]

Vallandigham crossed back to the US "under heavy disguise" on June 14 and gave a passionate speech at an impromptu Democratic convention in Hamilton, Ohio, the next day.[47] In that speech, he felt it necessary to lie about his involvement in a "subversive organization" that he failed to name.[48]

Lincoln was informed of his return. On June 24, 1864, Lincoln drafted a letter to Governor Brough and General Samuel P. Heintzelman and stated to "watch Vallandigham and others closely" and to arrest them if necessary. However, he did not send the letter, and it appears that he decided to do nothing about Vallandigham's return.[49] In late August, Vallandigham openly attended the 1864 Democratic National Convention in Chicago as a district delegate for Ohio.[50]

The reception by the convention to Vallandigham was mixed. Vallandigham received "vehement applause."[51] At one point, Vallandigham's name was called out by the audience and the response was "applause and hisses."[52] There were "cheers and hisses" on another occasion that he spoke.[53]

Vallandigham promoted the "peace plank" of the platform, which declared the war a failure and demanded an immediate end of hostilities.[54] In his acceptance letter, George B. McClellan made peace conditional on the Confederacy being ready for peace and to rejoin the Union.[55] McClellan's stance conflicted with the Democratic Party Platform of 1864 which stated that "immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention of the States, or other peaceable means, to the end that, at the earliest practicable moment, peace may be restored on the basis of the Federal union of the States."[56] Vallandigham supported his party's nomination of McClellan for the presidency but was "highly indignant" when McClellan repudiated the party platform in his letter of acceptance of the nomination.[57] For a time, Vallandigham withdrew from campaigning for McClellan.[58] The contradiction between the party platform and McClellan's views weakened Democratic efforts to win voters over.

In late September 1864, the conspiracy trial of Harrison H. Dodd, William A. Bowles, Andrew Humphreys, Horace Heffren, and Lambdin P. Milligan, members of the Knights of the Golden Circle, a paramilitary organization that had been founded in Cincinnati in 1854, morphed into the Order of American Knights, and become the Sons of Liberty, began in Indianapolis before a military commission. George E. Pugh testified as a government witness.[59] Testimony confirmed Vallandigham was "Supreme Commander,"[60] and James A. Barrett was the "Chief of Staff" to Vallandigham.[61] Witnesses testified that a mysterious Mr. Piper had communicated to them on behalf of Vallandigham.[60] According to the testimony of Felix G. Stidger, an undercover federal agent who had infiltrated the Knights of the Golden Circle, the plan of Vallandigham was to begin a revolt sometime between November 3 and 17.[62] The case went to the US Supreme Court, which in 1866 in Ex parte Milligan, ruled that the use of military tribunals to try civilians is unconstitutional if civil courts are still operating.

In April 1865, Vallandigham testified at the conspiracy trial of the American Knights in Cincinnati. He admitted to conversing with Jacob Thompson, the Confederate agent in Canada.[63] The intended revolt never materialized.

Post-war

[edit]In 1867, Vallandigham continued his stance against African-American suffrage and equality.[64] However, his views later changed with the New Departure policy.

Vallandigham returned to Ohio, lost his campaigns for the Senate against Judge Allen G. Thurman[65] and the House of Representatives against Robert C. Schenck[66] on an anti-Reconstruction platform. He then resumed his law practice.

In 1871, Vallandigham won the Ohio Democrats over to the "New Departure" policy, which would essentially neglect to mention the Civil War, "thus burying out of sight all that is of the dead past, namely, the right of secession, slavery, inequality before the law, and political inequality; and further, now that reconstruction is complete, and representation within the Union restored." He also affirmed "the Democratic party pledges itself to the full, faithful, and absolute execution and enforcement of the Constitution as it now is, so as to secure equal rights to all persons under it, without distinction of race, color, or condition." It also called for civil service reform and a progressive income tax (items 10 and 12). It was against the "Ku-Klux Bill" (item 17).[67] "New Departure" was endorsed by Salmon P. Chase, a former Lincoln cabinet member and Chief Justice of the United States.[68]

Death and burial

[edit]Vallandigham died in 1871 in Lebanon, Ohio, at the age of 50, after he accidentally shot himself in the abdomen with a pistol. He was representing a defendant, Thomas McGehean,[69] in a murder case for killing a man in a barroom brawl in Hamilton, Ohio. Vallandigham attempted to prove the victim, Tom Myers, had in fact accidentally shot himself while he was drawing his pistol from a pocket while rising from a kneeling position. As Vallandigham conferred with fellow defense attorneys in his hotel room at the Lebanon House, later the Golden Lamb Inn, he showed them how he would demonstrate this to the jury. Selecting a pistol he believed to be unloaded, he put it in his pocket and enacted the events as they might have happened, snagging the loaded gun on his clothing and unintentionally causing it to discharge into his stomach.

Although he was fatally wounded, Vallandigham's demonstration proved his point, and the defendant, Thomas McGehean, was acquitted and released from custody (only to be shot to death four years later in his saloon).[70] Surgeons probed for the pistol ball, thought to have lodged in the vicinity of Vallandigham's bladder, but were unable to locate it, and Vallandigham died the next day of peritonitis. His last words expressed his faith in "that good old Presbyterian doctrine of predestination".[71] Survived by his wife, Louisa Anna (McMahon) Vallandigham, and his son Charles Vallandigham, he was buried in Woodland Cemetery in Dayton, Ohio.

Legacy

[edit]Vallandigham was eulogized by James W. Wall, a former senator from New Jersey, who mentioned recently meeting with him about "New Departure".[72] Wall had been imprisoned during the Civil War by Union authorities.

John A. McMahon, Vallandigham's nephew, was also a U.S. Representative from Ohio.

In popular culture

[edit]Vallandigham's deportation to the Confederacy prompted Edward Everett Hale to write "The Man Without a Country."[73] The short story, which appeared in The Atlantic Monthly in December 1863, was widely republished. In 1898, Hale made the assertion that Vallandigham stated "he did not want to belong to the United States."[74]

Vallandigham is a character in some alternate history novels. In Ward Moore's Bring the Jubilee (1953) and William Gibson and Bruce Sterling's The Difference Engine (1990), Vallandigham defeated Lincoln in the presidential election of 1864 after the South won the Civil War. In Harry Turtledove's The Guns of the South (1992), he is elected vice-president in the same year for the same reason.

In CBBC's Horrible Histories, Vallandigham is played by Ben Willbond. In Horrible Histories he is shown as an excellent lawyer who is, however, extremely embarrassed by the idiotic way in which he died: by having killed himself by accident while he was defending his client, Thomas McGehean.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Copperhead (politics)

- List of unusual deaths

- List of people pardoned or granted clemency by the president of the United States

References

[edit]- ^ William Marvel (2010). The Great Task Remaining: The Third Year of Lincoln's War. ISBN 978-0547487144. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, pp. 7–10.

- ^ a b c "Clement Vallandigham", Ohio History Central.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, pp. 24, 31.

- ^ Flower, Frank Abail. Edwin McMasters Stanton, the Autocrat of Rebellion, Emancipation and Reconstruction. p. 252 fn, Boston, MA: George M. Smith & Co., 1905.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 53.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 100.

- ^ "John Brown and the Harper's Ferry Insurrection". Republican Banner (Nashville, Tennessee). November 2, 1859. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Vallandigham, Clement Laird, Speeches, Arguments, Addresses and Letters of Clement L. Vallandigham, pp. 201–205, New York: J. Walter and Co., 1864.

- ^ a b "(Untitled)". The Liberator. Boston, Massachusetts. November 11, 1859. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Clement L. Vallandigham", National Park Service.

- ^ "Representative Clement Vallandigham of Ohio", Historical Highlights, US House of Representatives.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 137.

- ^ Vallandigham, Clement Laird. "The Great American Revolution of 1861", The Congressional Globe: Containing the Debates and Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth Congress: Also of the Special Session of the Senate, edited by John C. Rives, 235–243. Washington, DC: Congressional Globe Office, 1861.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, pp. 205–207.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, pp. 215–217.

- ^ Kirkland, Edward Chase. The Peacemakers of 1864, p. 35, New York: The MacMillan Company, 1927.

- ^ Vallandigham, Clement Laird. "The Constitution – Peace – Reunion". Appendix, Congressional Globe: Containing the Speeches, Important State Papers and the Laws of the Third Session Thirty-Seventh Congress, edited by John C. Rives, 52–60. Washington, DC: Globe Office, 1863.

- ^ Vallandigham, Clement Laird, The Trial Hon. Clement L. Vallandigham, by a Military Commission: and the Proceedings Under His Application for a Writ of Habeas Corpus in the Circuit Court of the United States for the Southern District of Ohio, p. 23. Cincinnati: Rickey and Carroll, 1863.

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham. Abraham Lincoln Complete Works. Edited by John G. Nicolay and John Hay. Vol. II. p. 239, New York: The Century Co., 1920.

- ^ Vallandigham 1863a, p. 11.

- ^ Vallandigham 1863a, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Porter, George Henry. Ohio Politics During the Civil War Period. p. 148, fn 1, New York. 1911.

- ^ Joshua E. Kastenberg, Law in War, Law as War: Brigadier General Joseph Holt and the Judge Advocate General's Department in the Civil War and Early Reconstruction, 1861–1865 (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2011), 106.

- ^ Vallandigham 1863a, p. 23.

- ^ Vallandigham 1863a, p. 33.

- ^ Id.

- ^ Vallandigham 1863a, p. 40.

- ^ Vallandigham 1863a, pp. 259–272.

- ^ Pittman, Benn, The Trials for Treason at Indianapolis, Disclosing the Plans for Establishing a North-Western Confederacy. p. 253, Cincinnati, OH: Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin, 1865.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, pp. 288–293.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 34.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 300.

- ^ "Vallandigham Meeting in Newark." The New York Times. May 31, 1863.

- ^ Porter 1911, p. 167.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, pp. 293–295.

- ^ Long, E. B., and Long, Barbara. The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

- ^ Jones, John Beauchamp, A Rebel War Clerks Diary at the Confederate States Capital, Volume I, pp. 357–358.

- ^ Reinish, Henery. "Vallandigham and the Invasion of Lee". The New York Times, September 4, 1863.

- ^ "Citizens, Patriots, and Soldiers Look Here!", Rare Americana.

- ^ "Clement Laird Vallandigham Biography Page". Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War. 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Buescher, John. "Civil War Peace Offers Archived 2010-12-02 at the Wayback Machine." Teachinghistory.org, accessed September 2, 2011.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 319.

- ^ Kirkland 1927, p. 39.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, pp. 373–374.

- ^ Castleman, John Breckenridge. Active Service. pp. 145–146, Louisville, KY: Courier-Journal Job Printing, 1917.

- ^ Porter 1911, p. 195.

- ^ Bordewich, Fergus M. (2020). Congress at War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 310–311. ISBN 978-0451494443.

- ^ Nicolay & Hay 1889, p. 535.

- ^ National Democratic Committee (1863). Official Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention Held in Chicago in 1864. Chicago: The Times Steam Book and Job Printer. p. 16.

- ^ National Democratic Committee 1863, p. 9.

- ^ National Democratic Committee 1863, p. 24.

- ^ National Democratic Committee 1863, p. 26.

- ^ Porter 1911, p. 196.

- ^ National Democratic Committee 1863, p. 60.

- ^ "'The 1864 Democratic Party Platform,' Teaching American History". Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 367.

- ^ Porter 1911, p. 197.

- ^ Pittman 1865, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b Pittman 1865, p. 24.

- ^ Pittman 1865, p. 28.

- ^ Pittman 1865, p. 25.

- ^ "The American Knights; The Testimony of Mr. Vallandigham", The New York Times. April 4, 1865.

- ^ "Vallandigham on the Issues of the Hour – Negro Suffrage and Negro Equality – The National Finances". The New York Times. August 14, 1867.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 422.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 430.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, pp. 438–444.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 446.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 516.

- ^ Cone, Stephen Decatur (1901). Biographical and historical sketches: a narrative of Hamilton and its residents from 1792... Hamilton, Ohio: Republican Publishing Company. p. 144.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, p. 529.

- ^ Vallandigham 1872, pp. 567–573.

- ^ Kass, Amy; Kass, Leon (2012). "National Identity and Why It Matters". What So Proudly We Hail. Making American citizens through literature. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Hale, Edward Everett. "The Man Without a Country". p. 116, The Outlook, May–August 1898.

Bibliography

[edit]- Kirkland, Edward C. (1927). The Peacemakers of 1864. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Nicolay, John; Hay, John (May 1889). "Abraham Lincoln: A History. Vallandigham". The Century. 38: 127–137.

- Pittman, Benn (1865). The Trials for Treason at Indianapolis, Disclosing the Plans for Establishing a North-Western Confederacy. Cincinnati, OH: Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin.

- Porter, George Henry (1911). Ohio Politics During the Civil War Period. New York: Kessinger.

- Vallandigham, Clement Laird (1863a). The Trial Hon. Clement L. Vallandigham, by a Military Commission: and the Proceedings Under His Application for a Writ of Habeas Corpus in the Circuit Court of the United States for the Southern District of Ohio. Cincinnati: Rickey and Carroll.

- Vallandigham, James (1872). A Life of Clement L. Vallandigham. Baltimore: Turnbull Brothers.

- Primary sources

- Vallandigham, Clement Laird (1863b). The Record of Hon. C. L. Vallandigham on Abolition, the Union, and the Civil War. New York : J. Walter & Co.

- Vallandigham, Clement Laird (1864). Speeches, arguments, addresses, and letters of Clement L. Vallandigham. New York : J. Walter & Co.

Further reading

[edit]- Gottlieb, Martin. Lincoln's Northern Nemesis: The War Opposition and Exile of Ohio's Clement Vallandigham (McFarland, 2021).

- Hosmer, James Kendall (1907). Outcome of the Civil War, 1863–1865. New York, London, Harper & Bros. (extensive coverage on Vallandigham)

- Hostetler, Michael J. "Pushing the Limits of Dissent: Clement Vallandigham's Daredevil Tactics." Free Speech Yearbook 43 (2009): 85–92.

- Hubbart, Hubert C. "'Pro-Southern' Influences in the Free West, 1840–1865," Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1933), 20#1 pp. 45–62 in JSTOR

- Klement, Frank L. The Limits of Dissent: Clement L. Vallandigham and the Civil War (1998), a standard scholarly biography

- Mackey, Thomas C. Opposing Lincoln: Clement L. Vallandigham, Presidential Power, and the Legal Battle over Dissent in Wartime (Landmark Law Cases and American Society). (University Press of Kansas, 2020) online review

- Randall, James G. (1926). Constitutional Problems under Lincoln. Urbana, University of Illinois Press.

- Roseboom, Eugene H. "Southern Ohio and the Union in 1863," Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1952) 39#1 pp. 29–44 in JSTOR

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 862.

External links

[edit]- 1820 births

- 1871 deaths

- 19th-century American legislators

- 19th-century American newspaper editors

- American anti-war activists

- American exiles

- American male journalists

- American politicians convicted of crimes

- Copperheads (politics)

- Democratic Party members of the Ohio House of Representatives

- People of Ohio in the American Civil War

- Politicians from Dayton, Ohio

- Lawyers from Dayton, Ohio

- Civilians who were court-martialed

- Washington & Jefferson College alumni

- Burials at Woodland Cemetery and Arboretum

- Accidental deaths in Ohio

- Firearm accident victims in the United States

- Deaths by firearm in Ohio

- Sprigg family

- People from Lisbon, Ohio

- Deaths from peritonitis

- Infectious disease deaths in Ohio

- Knights of the Golden Circle members

- John Brown (abolitionist)

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Ohio

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States military

- Recipients of American presidential clemency