Omega SA

| |

Boutique on Fifth Avenue, Manhattan | |

Native name | Omega Société Anonyme (SA) |

|---|---|

| Formerly |

|

| Company type | Subsidiary |

| Industry | Watchmaking |

| Founded | 1848 in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland |

| Founder | Louis Brandt |

| Headquarters | , |

Number of locations | Australia, Denmark and Sweden |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Raynald Aeschlimann (President) |

| Products | Watches |

| Parent | The Swatch Group |

| Website | omegawatches.com |

Omega SA is a Swiss luxury watchmaker based in Biel/Bienne, Switzerland.[1] Founded by Louis Brandt in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1848, the company formerly operated as La Generale Watch Co. until incorporating the name Omega in 1903, becoming Louis Brandt et Frère-Omega Watch & Co.[2][3][4] In 1984, the company officially changed its name to Omega SA[5] and opened its museum in Biel/Bienne to the public.[6][7] Omega is a subsidiary of The Swatch Group.[1]

Britain's Royal Flying Corps used Omega watches in 1917 for its combat units, followed by the U.S. Army in 1918, and NASA in 1969 for Apollo 11.[8] Omega has been the official timekeeper of the Olympics since 1932[9] and is the current timekeeper of the America's Cup yacht race. Omega was a main partner of the 2022 Winter Olympics.[10][11]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The forerunner of Omega, La Generale Watch Co., was founded at La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, in 1848 by Louis Brandt, who assembled key-wound precision pocket watches from parts supplied by local craftsmen.[12] He sold his watches from Italy to Scandinavia by way of England, his chief market. In 1894, his two sons Louis-Paul and César developed their own in-house manufacturing and total production control system that allowed component parts to be interchangeable. Watches developed with these techniques were marketed under the Omega brand of La Generale Watch Co. By 1903, the success of the Omega brand led La Generale Watch Co to spin off Omega as its own company, and the Omega Watch Co was officially founded in 1903.

Re-organization

[edit]

Louis-Paul and César Brandt both died in 1903, leaving one of Switzerland's largest watch companies — with 240,000 watches produced annually and employing 800 people — in the hands of four young people, the oldest of whom, Paul-Emile Brandt, was not yet 24.[13] The economic difficulties brought on by the First World War led Paul-Emile Brandt to work in 1925 towards the union of Omega and Tissot, then to their merger in 1930 into the group SSIH, Geneva.

Under Brandt's leadership and Joseph Reiser's from 1955, the SSIH Group continued to grow and multiply, absorbing or creating some fifty companies, including Lanco and Lemania, manufacturer of the most famous Omega chronograph movements. By the 1970s, SSIH had become Switzerland's top producer of finished watches and third in the world. Up to this time, Omega outsold Rolex, its main Swiss rival in the luxury watch segment, in the race for "King of Swiss Watch brands", although Rolex sold at a higher price point. Omega tended to be more revolutionary and more professionally focused, while Rolex watches were more ‘evolutionary’ and famous for their mechanical pieces and branding.[14][15][16]

While Omega and Rolex had dominated in the pre-quartz era, this changed in the 1970s during the quartz crisis, when Japanese watch manufacturers, such as Seiko and Citizen, rose to dominance due to their use of quartz movements. In response, Rolex continued concentrating on its expensive mechanical chronometers where its expertise lay (though it did have some experimentation in quartz), while Omega tried to compete in the quartz watch market with its own quartz movements.[14]

Recent development

[edit]

Weakened by the severe monetary crisis and recession of 1975 to 1980, SSIH was bailed out by banks in 1981.[17] During this period, Seiko expressed interest in acquiring Omega, but nothing came of the talks.

Switzerland's other watch making giant Allgemeine Schweizerische Uhrenindustrie AG (ASUAG), supplier of a large range of Swiss movements and watch assemblies, was in economic difficulty. It was the principal manufacturer of Ébauche (unfinished movements) and owner, through their sub-holding company General Watch Co (GWC), of various other Swiss watch brands including Longines, Rado, Certina, Hamilton Watch Company and Mido. After drastic financial restructuring, the R&D departments of ASUAG and SSIH merged production operations at the ETA complex in Granges. The two companies completely merged forming ASUAG-SSIH, a holding company, in 1983.

Two years later, the holding company was taken over by a group of private investors led by Nicolas Hayek. Renamed Société de Microélectronique et d'Horlogerie (SMH), the new group over the next decade proceeded to become one of the top watch producers in the world.[18] In 1998 it became The Swatch Group, which now manufactures Omega and other brands such as Blancpain, Swatch, and Breguet.

Omega experienced a resurgence with advertisements that focused on product placement strategies, such as in the James Bond 007 films; the character had previously worn a Rolex Submariner but switched to the Omega Seamaster Diver 300M with GoldenEye (1995), and later an Omega Planet Ocean and Aqua Terra. Omega adopted many elements of Rolex's business model (i.e. premium pricing, tighter controls of dealer pricing, increasing advertising, etc.), which succeeded in increasing Omega's market share and name recognition to become a direct competitor to Rolex.[14][19][20]

In 2019, Omega licensed its name and branding to Marcolin for a collection of men's and women's optical frames and sunglasses.[21] In March 2022, Omega collaborated with sibling company Swatch, both of which are owned by The Swatch Group, to release a budget version of its iconic Omega Speedmaster Moonwatch.[22] The so-called "MoonSwatch", available in 11 colors, is made of bioceramic (a mixture of ceramic and castor oil) and priced at $260 / £207,[23] well below the $5,250 price (as of March 2022) of the least expensive Omega Speedmaster Moonwatch.[24]

Watch manufacturing

[edit]Notable inventions and patents

[edit]

- In 1892, Louis Brandt, the founder of Omega, manufactured the world's first minute repeating wristwatch in collaboration with Audemars Piguet, which provided the minute-repeating movement.[25][26][27] The 18K-gold watch is now kept in the Omega Museum in Biel/Bienne, Switzerland.[27]

- In 1947, Omega created the first tourbillon wristwatch calibre in the world with the 30I. Twelve of these movements were made, intended for inclusion in the observatory trials in Geneva, Neuchâtel and Kew-Teddington, and they were known as the Omega Observatory Tourbillons. Unlike conventional Tourbillion movements whose cages rotate once per minute, the 30I's cage rotated one time each seven and a half minutes. In 1949, one of these delivered the best results ever recorded by a wristwatch up to that time. A year later, Omega broke its own record in the Geneva Observatory Trials of 1950.[28]

- In 1999, after the successful development of Calibre 2500, Omega made history by introducing the first mass-produced watch incorporating the coaxial escapement — invented by English watchmaker George Daniels.[29] Considered by many to be one of the more significant horological advances since the invention of the lever escapement, the coaxial escapement functions with virtually no lubrication, thereby eliminating one of the shortcomings of the traditional lever escapement.[30] Through using radial friction instead of sliding friction at the impulse surfaces the coaxial escapement significantly reduces friction, theoretically resulting in longer service intervals and greater accuracy over time.[31]

- On January 24, 2007, Omega unveiled its new Calibres 8500 and 8501, two coaxial (25,200 bph) movements created exclusively from inception by Omega.[32][33]

- On January 17, 2013, Omega announced the creation of the world's first movement that is resistant to magnetic fields greater than 1.5 Tesla (15,000 Gauss), far exceeding the levels of magnetic resistance achieved by any previous movement - a similar movement was used by Daniel Craig as James Bond, though the official collectors watch was labelled as resistant to 15,007 Gauss in honor of the fictional secret agent's codename. Most anti-magnetic watches utilize a soft iron - Faraday cage which distributes electromagnetism in such a way that it cancels the effect on the movement contained within. This type of anti-magnetic case required de-magnetizing procedures of the case. Omega has instead built a movement of non-ferrous materials eliminating the need for such a cage and providing a far greater resistance to magnetic fields eliminating necessity of additional maintenance.[34]

- In 2015, they introduced the Master Chronometer Certification, which denotes that along with a COSC (Official Swiss Chronometer Testing Institute) certification, a movement has also passed a series of eight tests set out by METAS (The Federal Institute of Metrology). Master Chronometer watches have a minimum water-resistance rating of 100 metres (330 ft) (the 2022 Speedmaster '57 is a Master Chronometer with 50 metres (160 ft) water-resistance),[35] a minimum power reserve rating of 60 hours, an accuracy rating of 0/+5 seconds per day, and are resistant to magnetic fields of 15,000 gauss. The Master Chronometer Certification debuted on the Globemaster but they now offer it across many more of its watch collections.[36]

Observatory trials

[edit]

Observatory trials focused on the science of Chronometry and the ability to make chronometers measure time precisely. Only Patek Philippe and Omega participated every year in the trials. Omega's performances at these competitions garnered the company a reputation of precision and innovation.[37]

For more than a decade (1958–1969), Omega was the largest manufacturer of COSC chronometers. Omega developed the slogan "Omega – Exact time for life" in 1931 based on its historical performance at the Observatory trials.[38] Omega's early prowess in designing and regulating timing movements was made possible by the company's incorporation of new chronometric innovations.[37]

Notable dates for the Omega precision records:[37]

- 1894: Creation of the 19 caliber named Omega. The company is renamed Omega from Louis Brandt et Frères in 1903[39] Omega participates for the first time at observatory trials in Neuenburg, Albert Willemin, Omega's first "regleur de précision", regulated the movement

- 1919: 1st Prize at observatory trials in Neuenburg with a 21 caliber, this caliber was slightly modified to become the Cal. 47.7

- 1922: Omega participates for the first time at observatory trials in Kew-Teddington, achieves 3rd place

- 1925: 1st place at observatory trials in Kew-Teddington with a Cal. 47.7 (95.9 of 100 points ex aequo with Ulysse Nardin), movement regulated by Gottlob Ith

- 1930: 1st place at observatory trials in Kew-Teddington (96.3 of 100 points ex aequo with Movado), movement regulated by Alfred Jaccard

- 1931: Omega achieves 1st place in all 6 categories at observatory trials in Geneva, movements, regulated by Alfred Jaccard

- 1933: A Cal. 47.7 regulated by Alfred Jaccard achieved the precision record at observatory trials at Kew-Teddington, achieved 97.4/100 points

- 1936: Another Cal. 47.7 regulated by Alfred Jaccard achieved the precision record of 97.8/100 points at Kew-Teddington, record not broken until 1965

- 1937: 1st place at Kew-Teddington with 97.3 points

- 1938: 1st place at Kew-Teddington with 97.7 points

- 1940: 1st place with Cal. 30mm at Kew Teddington, movement regulated by Alfred Jaccard

- 1945: 1st place with 30mm caliber at the observatory in Geneva, movement regulated by Alfred Jaccard

The distinctive Omega Constellation day-date model of 1980's generation that was known as "Manhattan", equipped with quartz movement, Cal. 1444 - 1948: 1st place at observatory trial in Neuenburg for 30mm caliber

- 1950: 1st place for tourbillon Cal. 30I at Geneva Trials, regulated by Alfred Jaccard

- 1951: 1st place at the observatory trials in Geneva

- 1952: 1st place at the observatory trials in Geneva

- 1954: New record in Geneva by Gottlob Ith

- 1955: Two new records at Neuenburg by Gottlob Ith

- 1956: Two 1st places at observatory trials in Neuenburg

- 1958: New record in Geneva movements regulated by Joseph Ory

- 1959: Two records in Neuenburg and one new record in Geneva, movement regulated by Joseph Ory

- 1960: One new record in Geneva, one new record in Neuenburg, and 1st place in Neuenburg, movement regulated by Joseph Ory

- 1961: Two new records in Geneva by Joseph Ory, the first four places for the 'single pieces' category in Geneva are occupied by Omega

- 1962: 2nd, 3rd and 4th places for Omega

- 1963: Two 1st places in Geneva and Neuenburg, movement regulated by Joseph Ory and André Brielmann

- 1964: New record in Neuchatel by Joseph Ory

- 1965: Omega occupies 2nd to 9th places

- 1966: Three new records for Omega (two in Neuenburg, one in Geneva)

- 1968: Omega enters with a tuning fork, movement regulated by André Brielmann for a new record

- 1969: Two new records for the tuning fork, movement regulated by André Brielmann

- 1970: One new record for the tuning fork, movement regulated by André Brielmann

- 1971: Two new records for the tuning fork, movement regulated by André Brielmann

- 1974: Omega Marine Chronometer certified as the world's first Marine Chronometer wristwatch, accurate to 12 seconds per year

Reference Numbers

[edit]Before 1962 it was a simple alphanumeric code of two letters followed by four digits. Between 1962 and 2007 Omega used the Mapics system, consisting of two letters followed by either six or seven numbers. The PIC system started in 1988, running concurrently with Mapics, and featured an arrangement of eight numbers in three groups (XXXX.XX.XX).[40]

Finally, today we have the PIC14 structure, with 14 digits in six groups.

Notable models

[edit]

- The Omega wristwatch Ref. H6582/D96043 (1960) once owned by Elvis Presley was sold in auction by Phillips for US$1.812 million in Geneva on May 12, 2018, making it the most expensive Omega timepiece ever sold at auction.[41][42] The watch was manufactured in 1960 and was sold by Tiffany & Co. in 1961.[42] The watch was presented to Elvis Presley as a gift from RCA Records on February 25, 1961, to commemorate his remarkable achievement of having sold 75 million records.[41] Petros Protopapas, the director of Omega Museum, later confirmed that the museum was the winning bidder.[43]

- The Omega Stainless Steel Tourbillon 301 was sold in auction by Phillips for around US$1.43 million (1,428,500 CHF) in Geneva on November 12, 2017.[44] It was then the most expensive Omega timepiece ever sold at auction.[45][46]

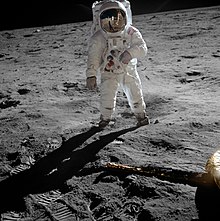

- In March 1965, the Omega Speedmaster was declared “Flight Qualified for all Manned Spaced Missions."[47] On July 20, 1969, Buzz Aldrin stepped onto the Moon wearing his Omega Speedmaster watch.[48] The model of the first watch on the Moon is the Omega Speedmaster 105.012.[49]

Historic events

[edit]

Space exploration

[edit]First worn by Mercury astronaut Wally Schirra in 1962, the "Omega Speedmaster Professional Chronograph" was chosen by NASA to become the only chronograph certified for use on all missions since 1965.[50]

The selection of the "Omega Speedmaster Professional Chronograph" for American astronauts was the subject of a rivalry between Omega and Bulova.[51]

All subsequent crewed NASA missions also used this handwound wristwatch. NASA started selecting the chronograph in the early 1960s. Automatic chronograph wristwatches were not available until 1969. Even so, all the instrument panel clocks and time-keeping mechanisms in the spacecraft on those space missions were Bulova Accutrons with tuning fork movements,[citation needed] because at the time NASA did not know how well a mechanical movement would work in zero gravity. [citation needed]

First watch on the Moon

[edit]The Omega Speedmaster Professional Chronograph was the first watch on the Moon, worn by Buzz Aldrin. Although Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong was first to set foot on the Moon, he left his 105.012 Speedmaster inside the Lunar Module Eagle as a backup because the LM's electronic timer had malfunctioned. Aldrin wore his, making his Speedmaster the first watch worn on the Moon. Armstrong's watch is displayed at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.[52][53] Aldrin's was stolen; he mentions in his 1973 book, Return to Earth, that when donating several items to the Smithsonian Institution his Omega was one of the few things stolen from his personal effects.[54]

In 2007, to mark the 50th anniversary of the Omega Speedmaster Professional Chronograph, Omega unveiled the commemorative Speedmaster Professional Chronograph Moonwatch. The watch had the distinctive features of the first hand-winding Omega Speedmaster introduced in 1957. It was sold in an edition of 1,957 pieces.[55]

Sponsorship

[edit]NCIS

In the US television series NCIS, lead actor Mark Harmon wears an Omega Seamaster Planet Ocean with supporting cast member Michael Weatherly wearing a matching version. In both cases, this is the stainless steel model with orange bezel and black dial.

Need for Speed

Omega is the official timekeeper for the video game Need for Speed II, released on Microsoft Windows and PlayStation in 1997.[56]

Kojak

In the US television series Kojak, lead actor Telly Savalas wore a gold-plated Omega Time Computer One, the first mass-produced LED watch.

James Bond

Omega has been associated with James Bond movies since 1995. That year, Pierce Brosnan took over the role of James Bond and began wearing the Omega Seamaster Quartz Professional (model 2541.80.00) in GoldenEye. In all later films, Brosnan wore an Omega Seamaster Professional Chronometer (model 2531.80.00). The producers wanted to update the image of the spy to a more distinctly sophisticated "Euro" look.[57] Omega was eager to participate in the high-profile product placement opportunity to further its brand image and supplied the watches.[58]

For the 40th anniversary of James Bond (2002) a commemorative edition of the watch was made available model 2537.80.00 (10,007 units). The watch is identical to the model 2531.80.00 except the blue watch dial had a 007 logo inscribed across it, machined into the case-back, and inscribed on the clasp.[59]

Daniel Craig, the current James Bond since Casino Royale, also wears an Omega Seamaster: the Seamaster Planet Ocean (model 2900.50.91) in the first part of Casino Royale, and the Seamaster Professional 300M (model 2220.80.00) in the latter part (from travelling to Montenegro). He mentions Omega by name when questioned by Vesper Lynd. With the launch of the film in 2006, Omega released a 007-special of the Professional 300M, (model 2226.80.00) featuring the 007-gun logo on the second hand and the rifle pattern on the watch face, based on the gun barrel sequence of Bond movies.[60]

Omega released a second James Bond limited edition watch in 2006, a Seamaster Planet Ocean model with a limited production of 5007 units. The model is similar to what Craig wears earlier on in the film; however, it has a small orange colored 007 logo on the second hand, an engraved caseback signifying the Bond connection, and an engraved 007 on the clasp.[61]

In the 2008 movie Quantum of Solace, Craig wears the Omega Seamaster Planet Ocean with a black face and steel bracelet (42mm version). Another limited edition was released featuring the checkered "PPK grip" face with the Quantum of Solace logo.[62] The third limited edition release from Omega came in 2012, based on the Planet Ocean Ref: 232.30.42.21.01.004. It featured a textured dial with the 007 logo at the 7 o'clock position and a 007 decorated rotor visible through the case-back.[63]

In 2015, two commemorative models were produced for the 24th Bond film, Spectre: the Omega Seamaster 300m master co-axial Ref: 233.32.41.21.01.001. 7007 units were produced and came with a NATO strap, as well as the standard bracelet. The watch featured a bi-directional bezel with a world timing scale, rather than the diving scale present on the standard 300m.[64] The second timepiece, the Omega Seamaster Aqua Terra 150m master co-axial Ref: 231.10.42.21.03.004, was decorated with a textured dial based on the Bond family coat of arms and a rotor resembling a bullet and gun barrel with "James Bond" inscribed.[65]

Sports sponsorship

Omega has frequently been the official timekeeper for the Olympics, beginning with the 1932 Summer Olympics. It was the official timekeeper for the 2006 Winter Olympics, 2008 Summer Olympics, 2010 Winter Olympics, and 2012 Summer Olympics.[66][67] In 2008, Omega released an Olympic edition watch with the Olympics logo on the second hand. Olympic swimmer and multiple gold medalist Michael Phelps is an Omega Ambassador and wears the Omega Seamaster Planet Ocean. In 2014, Omega became the official timekeeper of the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics. The brand was a Worldwide Olympic Partner at the 2016 Summer Olympics. After the 2020 Summer Olympics were postponed due to COVID-19, the Tokyo Station's Olympic countdown clock, made by Omega, which was displaying the number of days until the Games, and a local tourist attraction, was halted and switched to show the current date and time.[68] This partnership will continue at least until 2032.[69]

Omega constructed and maintained a monochrome video scoreboard for Milwaukee's County Stadium, the former home of Major League Baseball's Milwaukee Brewers, which was in use from the board's construction in 1980 until the stadium's closure in 2000.[70]

Providing support to Emirates Team New Zealand and representing the team's official watch, in 2007 Omega introduced the Seamaster NZL-32 chronograph, named after the boat that won America's Cup in 1995. The watch was developed in cooperation with Dean Barker, skipper of Team New Zealand and Omega Ambassador.[71]

On July 1, 2011, Omega became the official timekeeper of PGA of America and signed a five-year agreement through 2016. The brand also sponsors the Dubai Desert Classic and the Omega European Masters.

Controversy

[edit]In December 2018, World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) released a report assigning environmental ratings to 15 major watch manufacturers and jewelers in Switzerland,[72][73] and Omega was given the lowest environmental rating, "Latecomers/Non-transparent", suggesting the manufacturer has taken few actions addressing the impact of its manufacturing activities on the environment and climate change.[72][73]

Omega faced activist pressure to withdraw from being the official timekeepers of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics after numerous governments enacted diplomatic boycotts over human rights violations (in particular China's repression of Uyghurs and other minorities, which some countries have designated as a genocide).[74] Omega defended its continued role as official time keeper of the Olympics by stating its policy to "not to get involved in certain political issues because it would not advance the cause of sport in which our commitment lies."[75] Omega has been the official timekeeper of the Olympics since 1932 including the controversial 1936 and 1980 Olympics, which also saw widespread boycotts over human rights concerns.[76][77]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Omega - Swatch Group". www.swatchgroup.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ "Brand - Fondation de la Haute Horlogerie". www.hautehorlogerie.org. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "10 Things to Know About Omega". WatchTime - USA's No.1 Watch Magazine. January 24, 2019. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "The History Of The Omega Watch Company". HallandLaddco. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ "1894: the New Omega 19-Ligne Calibre Inspired a New Company Name". Omega. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Omega Museum in Biel - Swatch Group". www.swatchgroup.com. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ "Omega Museum". MySwitzerland.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Bailham, Lee; Eric Jones. "Omega Speedmaster Professional Chronographs". NASA. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ^ "Highlights of Olympic Timekeeping". Omega SA. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ^ "News - Omega Seamaster Diver 300M America's Cup Chronograph". Monochrome Watches. February 22, 2021. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Neate, Rupert (November 12, 2021). "Winter Olympics top sponsors 'silent' over China's human rights record". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ "Omega: the first 100 years". Omega Museum. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Richon, Marco. 2007 Omega: A Journey through Time.

- ^ a b c "Rolex Vs Omega: Which Should You Buy?". Blowers Jewellers. March 19, 2019. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ "Comparative Review of the Omega Seamaster Professional Model2254.50.00 VS. The Rolex Submariner 16610 | Luxury Tyme: The Rolex Reference Page". Luxury Tyme. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ^ "Comparative Review of the Rolex Sea-Dweller VS. Omega Planet Ocean". The Seamaster Reference Page. August 3, 2010. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ^ Conklin, David W. (2006). Cases in the Environment of Business: International Perspectives. SAGE. ISBN 9781412914369.

- ^ According to the DowJones Market Bulletin of January 18, 2008.

- ^ "Bonding With Time – The Wristwatches of James Bond". Jamesbond.ajb007.co.uk. June 29, 2006. Archived from the original on December 14, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ^ "The Most Popular Swiss Watch Brands: Rolex, Tag Heuer, Breitling and Wenger | Swiss Watch Guide". Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Turra, Alessandra (October 8, 2019). "Marcolin to Develop Omega and Longines Eyewear Collections". Women’s Wear Daily. Archived from the original on September 3, 2022. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ^ Evans, Jonathan (March 24, 2022). "The Omega x Swatch 'MoonSwatch' Brings the Speedmaster to the Masses". Archived from the original on March 25, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ White, Jeremy (March 24, 2022). "Omega and Swatch's $260 MoonSwatch Looks Out of This World". Wired. Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "Moonwatch Professional Chronograph 42 MM 311.33.42.30.01.001 Steel on leather strap". Archived from the original on February 15, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ Brunner, Gisbert (July 12, 2018). "7 Milestone Omega Watches, from 1892 to Today". WatchTime - USA's No.1 Watch Magazine. Archived from the original on February 4, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ "Innovation: Tradition & Avant-garde". Audemars Piguet - Le Brassus. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Tan, Timmy. "The world's first wristwatch minute repeater: Still sound". Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ "OMEGA Watches: The Collection". OMEGA Watches. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Omega Co-Axial 2500". Archived from the original on January 7, 2009. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ^ See Europa Star technical notes Archived April 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Woodward, P (August 2004). "Performance of the Daniels Coaxial Escapement" (PDF). Horological Journal: 283–285. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2004. (archived August 7, 2004)

- ^ "Omega Watches: Planet Omega". Omega Watches. Archived from the original on May 26, 2008. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Computerized Machines Aid Human Watchmakers". International Herald Tribune. September 5, 2012. Archived from the original on May 10, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017 – via The New York Times.

- ^ Omega Watches, Omega announces the first truly anti-magnetic watch movement Archived April 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Speedmaster '57". Omega Watches. Archived from the original on December 31, 2022. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ "Omega". Bob's Watches. Archived from the original on December 27, 2019. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Official PuristSPro Reviews of luxury Wristwatches for Collectors & buyers". PuristSPro. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ^ "Art, Culture & Luxury". Omega: a Cultural Icon – Blog. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ "First 100 Years". Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Complete Omega Serial Numbers Guide". The Watch Standard. July 22, 2021. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ a b "Elvis Presley's Omega Sells For $1.8 Million, Setting A New World Record For An Omega". Phillips. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ a b "Phillips: CH080118, Omega". Phillips. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ "SJX Watches". watchesbysjx.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ "Phillips: CH080217, Omega". Phillips. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ Bues, Jon (November 12, 2017). "Auction Report: Omega Stainless Steel Tourbillon Achieves CHF 1,428,500 at Phillips, Making It The Most Expensive Omega Ever Sold". Hodinkee. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ "New Record Set for Most Expensive Omega Wristwatch Sold to Date at CHF 1,428,500". Revolution. November 13, 2017. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ Cusano, Claudia (2015). "The First Watch on the Moon: the Omega Speedmaster". Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "The first watch worn on the moon". Summer 2009. Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ SwissWatchExpo (August 7, 2020). "Which Omega Speedmaster Went to the Moon?". Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ Robert Z. Pearlman (January 13, 2021). "Omega debuts next generation of NASA-qualified Speedmaster moonwatches". Space.com. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Alan A. Nelson, "The Moon Watch: A History of the Omega Speedmaster Professional", NAWCC Bulletin, February 1993.

- ^ Omega Speedmaster Professional Chronographs Archived February 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Apollo Lunar Surface Journal Archived November 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, 2004.

- ^ "Omega Speedmaster Watches". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Alan A. Nelson,The Moon Watch: A History of the Omega Speedmaster Professional Archived January 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine", NAWCC Bulletin via [1] Archived January 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, February 1993 issue (retrieved on 2007-02-21).

- ^ "New Omega Speedmaster Moonwatch - a Piece of Space History". Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "Need for Speed II SE, GameFAQs Reader Screenshot: A Ford Indigo in Need For Speed 2 SE". GameFAQs. NoMercyKing. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ^ "James Bond's Choice: The Omega Seamaster Archived 2009-07-05 at the Wayback Machine", commanderbond.net, 2004-03-29 (retrieved on 2007-02-21).

- ^ "The 007 Connection Archived January 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine", chronocentric.com (retrieved on 2007-02-21).

- ^ Lara Magzan, "The business of Bond...James Bond Archived October 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine", CNN/Money, 2002-11-25 (retrieved on 2007-02-21).

- ^ Devin Zydel, "Omega Presents James Bond Exhibition in Geneva Archived 2008-09-18 at the Wayback Machine", Commanderbond.net 2007-01-06 (retrieved on 2007-02-21).

- ^ Devin Zydel, "Omega Casino Royale Limited Series Planet Ocean Watch Announced Archived 2009-07-08 at the Wayback Machine", commanderbond.net 2006-11-05 (retrieved on 2007-02-21).

- ^ Omega "[2] Archived 2014-04-08 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ "Omega Co-Axial 42 mm". OMEGA Watches. Archived from the original on November 14, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ "Omega Seamaster 300 SPECTRE Limited Edition". Bond Lifestyle. September 25, 2015. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ "Omega Seamaster Aqua Terra 150M Limited Edition". Bond Lifestyle. September 25, 2015. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ "Official Timekeeper Omega unveils the Vancouver 2010 Countdown Clock Archived February 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine", Olympic.org, 2007-02-13 (retrieved on 2007-02-21).

- ^ "OMEGA Watches: Planet OMEGA". Archived from the original on May 28, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- ^ "The countdown clock is clicking again for the Tokyo Olympics". USA Today. March 31, 2020. Archived from the original on April 1, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "IOC and official timekeeper Omega extend global Olympic partnership to 2032". International Olympic Committee. Lausanne. May 15, 2017. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Prigge, Matthew J. (September 26, 2016). "The County Stadium Scoreboard: Big, Ugly and Misunderstood". Shepherd Express. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

By the time the team was preparing to move into Miller Park, the County Stadium was the only park in baseball without a color board.

- ^ "New Omega Seamaster - Developed In the Regatta Spirit". Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ a b "Environmental rating and industry report 2018" (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ a b "Swiss luxury watches fail to meet environmental standards". SWI swissinfo.ch. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Mather, Victor (February 6, 2022). "The Diplomatic Boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympics, Explained". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "The U.S. government is boycotting the Beijing Olympics over human rights. Coke and Airbnb are still on board". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on February 21, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "1936: Omega Timed the Performances of Olympic Runners". Omega. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Sevastopulo, Demetri; Germano, Sara; Edgecliffe-Johnson, Andrew; Ahmed, Murad (May 6, 2021). "Olympics sponsors duck questions over Beijing 2022 as boycott calls grow". Financial Times. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.