Danish state bankruptcy of 1813

Frederik VI, King of Denmark, 1809 | |

| Date | 5 January 1813 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 56°15′50″N 9°30′06″E / 56.2639°N 9.5018°E |

| Type | State bankruptcy |

| Cause |

|

| Outcome |

|

The Danish state bankruptcy of 1813 was a domestic economic crisis that began in January 1813 and had consequential effects until 1818.[1] As Denmark–Norway struggled with the financial burden that the Napoleonic Wars had on the economy, the devaluation of the currency had negative effects on merchants, citizens and businesses alike.[2]

As Denmark-Norway allied with France in 1807 in the aftermath of British attacks on Copenhagen, it incurred costs of rearmament as machinery, equipment and supplies were required for wartime efforts.[3] As a result, when the economic burden placed on the state began to take its toll, the collapse of the currency became imminent.[4] The loyalty shown to Napoleon and France by Frederik VI and Denmark-Norway was eventually cause for great loss. The Treaty of Kiel, signed in January 1814, saw Denmark lose considerable power in Europe. Frederik VI had to renounce the Kingdom of Norway to Charles XII, the king of Sweden. This event put even further pressure on export and import trading, as well as an already weak economy.[5]

Due to consequences of the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark-Norway was forced to declare bankruptcy on 5 January 1813.[6] The government through monetary and economic policy had two main objectives; stabilise the economy and create a unified state-wide monetary system.[7] The Rigsbank was the first governmental institution tasked with stabilising the economy by re-structuring the currency. In 1818, the Nationalbank, a privately operated institution was formed to extend credit benefits from citizens to businesses, and aid the revival of the Danish economy.[6] The objective was to reinstate silver as the overarching currency in the Danish economy and restore confidence in a central banking system.[7]

History

[edit]Napoleonic Wars

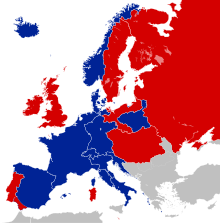

[edit]Denmark-Norway had remained adjacent to early proceedings[clarification needed] of the Napoleonic Wars. Russia and France both had vested interests in Denmark-Norway and its naval fleet and its use of Norwegian-Danish trade routes.[8] The British understood they would need to lay siege to the fleet if they were to gain control over vital sea lanes.[9] In September 1807, the British empire bombed Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark, in order to capture or destroy the Dano-Norwegian fleet. The bombardment on the Danish capital allowed the British to take vital sea lanes in the Baltic and North Sea.[8] Frederik VI and his monarchy viewed the ruling of Norway as essential to its European power.[10] A lack of stability in the Norwegian grain supply as well as the chance for French invasion drove the strategy for an alliance with Napoleon.[10]

Denmark-Norway had little to offer France as the naval strength had been eliminated. The cost of rearmament and war time preparations took a toll on the Danish-Norwegian economy.[4] Adding to the loss in the attack on Copenhagen in 1807, Frederik VI remained loyal to Napoleon and France, even as Sweden and Russia switched alliances to Great Britain.[11] When France attacked Russia in 1812, both nations effectively allied with Great Britain, leaving their alliance with France behind. After suffering a prolonged period of defeat between 1810 and 1812, King Frederik VI was increasingly concerned about losing claims to Norway and the lands owned in the North of Germany.[2]

Bankruptcy declared

[edit]On 5 January 1813 Denmark-Norway declared bankruptcy and a new state bank, the Rigsbank, was created to bring the economy out of hardship.[7] The main agenda for the Rigsbank was to re-organise and stabilise the state's monetary system.[7] When Denmark-Norway allied with France in 1807, the Treaty of Fontainebleau was signed between France and Denmark-Norway. Denmark-Norway was promised favourable loans and subsidies that would cover financial costs of wartime readying.[2] However, the terms of the treaty were not upheld and it was Denmark-Norway who covered the cost of the French push in Denmark in 1808.[2] Adding to this, the promise of troops and equipment to Napoleon throughout the war only furthered the costs Denmark-Norway were to bear.

Treaty of Kiel, 1814

[edit]The Treaty of Kiel was a 14 article document signed in January 1814 between Denmark-Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom, ending the Napoleonic wars.[12] Sweden and the United Kingdom, under the sixth coalition were united in battle against Denmark and Norway who was allied with France.[10] Denmark, due to its defeat in the war and the ensuing Treaty of Kiel, were obligated to cede Heligoland to the United Kingdom.[13] King Frederik VI Denmark's rule of the Kingdom of Norway was relinquished to King Charles XIII of Sweden, a great disappointment to King Frederik VI.[14]

Under Article III, Denmark were able to get ruling geographical claims on Greenland, Iceland and the Faroe Islands.[15] The culmination of significant land claim losses, the dissolution of the union with Norway, and the humiliation of defeat to the United Kingdom and its allies, had severe economic and social impacts on Denmark.[7]

Causes of bankruptcy

[edit]Internal

[edit]The cost of wartime efforts had a major effect on the Danish-Norwegian economy. In an effort to subsidise the cost of rearmament, the Danish government issued a substantial amount of banknotes.[10] As it stood, the national currency was silver and as a result of excessive issue of banknotes, the former value of silver was lost. The Danish government could not ensure loans from the population were paid, leading to an excessive printing of more money to account for wartime expenditure.[4] Denmark's efforts to prepare for the war economically led to the devaluation of the currency.

The indecisiveness of Frederik VI, the king of Denmark, to not act in the interests of Denmark by remaining loyal to Napoleon and France in 1812, was cause for significant loss of power.[10] As France and her allies were defeated, king Frederik VI surrendered the kingdom of Norway to the king of Sweden and lost claim to significant land claims in North Germany[2] As a result, financial pressure on the currency was increased and not only had great effects on the economy, but led to poverty and a reduction in the quality of life for citizens.[16]

External

[edit]Britain's bombardment of Copenhagen in September 1807 ended the neutrality of Denmark in the Napoleon war. Denmark-Norway were forced to ally with France, with little military power after losing their naval fleet. The trade embargo on Denmark by Britain coupled with the destruction of the Danish naval fleet saw trade between Norway and Denmark essentially ceased.[17]

The alliance between Denmark-Norway and France was a key reason for the loss of Norway to Sweden in the Treaty of Kiel.[8] Norway was aligned with the economic motives of Great Britain and the loss of trade between Denmark and Norway due to the blockade, saw trade between Norway and Great Britain begin. The decision to join the war along with the effects of the trade embargo meant significant financial burden would be placed on the state to ready for battle as the control of the vital sea lanes was lost.[18]

Effects

[edit]Economic

[edit]Frederik VI's decision to halt all trade with Britain following on from the bombardment of Copenhagen, negatively affected the import and export market. The Danish timber market was dependent on trade to other European nations and reported a drop of 99% from 1806 to 1808.[19] Throughout the period from 1808 to 1813, inflation was rising and in 1813 alone prices rose by some 300 per cent.[4] The central government lost faith in the Danish currency, evidenced by certain taxes being payable by kind (grain) instead of banknotes.[4] The Treaty of Kiel and the loss of geographic claim saw Denmark encounter problems with the circulation of banknotes. As Denmark's total population reduced, this was not met with a reduction in the stock of circulating banknotes, only increasing inflationary effects on the currency.[4] As a result of the war, Denmark was forced to suspend foreign debt and interest payments until 1815.[20]

Political

[edit]Denmark-Norway, before France was defeated by Russia in 1812, were offered permission to side with Britain and its allied forces.[21] This would have reduced the burden that was placed on Denmark following the war and allowed the state to retain claims to land already conquered. Michael Bregnsbo, argues that Frederik VI was loyal to Napoleon, as he believed Napoleon would be the leading figure in the peace proposals if victory was achieved.[10] Historian, Morten Ottosen, argues that the stubbornness of Frederik VI in remaining loyal to Napoleon was foolish and was at the heart of future failures.[2]

Social

[edit]The British blockade on Norway and Denmark was having consequences on the entire population.[22] The halting of trade meant employment opportunities stopped as goods were not being made, financial incentives were not either. In response to the bombardment of Copenhagen, King Frederik VI, prohibited all trade and communication with Great Britain in 1807.[2] However, merchants and citizens understood the need for a relaxed prohibition as British goods were valued at a premium.[2]

Instances of corruption were widespread as the financial burden of inflation and lower wages took a toll on the population. Civil servants were increasingly being tried for corruption, most commonly, in regards to embezzlement.[22] The betrayal of the King by his civil servants put pressure on the monarchy to instil public confidence in an absolutist rule in order to dispel ideas of democracy.[22]

Economic resolution

[edit]

Rigsbanken

[edit]On 5 January 1813 the "Decree on changing the currency system for the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway and the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein” was declared by the Minister for Finance, Ernst Schimmelmann.[4] The Decree stated:

“Since the government’s existing currency system is shaken to the core, we have decided to bring order and stability to the system by establishing a permanent and unshakeable foundation for it".[23]

The revival of the economy began with the establishment of the Rigsbanken, who were given authority to re-issue banknotes in a new currency, the rigsbankdaler. A compulsory 6% priority mortgage rate was to be paid in silver as well as a 61⁄2% interest rate placed on all real estate.[1] The government had requested the donation of silver or currency in the form of a loan to further add strength to the newly established Rigsbanken.[2] This immediate cash inflow became the basis of the Rigsbank's allocation of capital. Remaining banknotes from the Napoleonic wars could be exchanged to the new currency at a ratio of 6:1, a great devaluation of finance. The objective; to cease the issuing of notes until silver and banknotes were interchangeable.[18]

Nationalbanken, 1818

[edit]On 4 July 1818, King Frederik VI enacted Denmarks Nationalbank, authorising the institution to operate as the central bank.[4] The Nationalbank’s constitution was signed and allowed the bank to have sole handling of the countries issuing of banknotes. It was formed to ensure independence from the government and provide assurance to the Danish people that in future the state would not over issue the currency.[6]

The Nationalbank halved the circulation of banknotes between 1818 and 1838, culminating in the restoration of silver and notes being of equal value in 1838.[6] The success of the Nationalbank is grounded in historical power. The institution is today the central bank in Denmark and is attributed with restoring financial trust.[6]

Stabilisation

[edit]The work of the Nationalbank and the Rigsbanken eventually stabilised the economy. During the period of bankruptcy, primary education between the ages of seven and fourteen was made compulsory, in an effort to minimise the disparity between the wealthy and peasant citizens, all of which were being affected.[24] In 1838, the circulation of banknotes and silver had reached equality. This meant that debt repayments began and the economy began to return to the once former power it originally held.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Talvio, Tuukka; von Heijne, Cecilia; Märcher, Michael (2010). Monetary boundaries in transition: a North European economic history and the Finnish War 1808–1809. The Museum of National Antiquities. ISBN 978-91-89176-41-6. OCLC 761549810.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Glenthøj, Rasmus; Ottosen, Morten Nordhagen (2014). Experiences of War and Nationality in Denmark and Norway, 1807–1815. doi:10.1057/9781137313898. ISBN 978-1-349-33786-6.

- ^ Feldbæk, Ole (2001). "Denmark in the Napoleonic Wars: A Foreign Policy Survey". Scandinavian Journal of History. 26 (2): 89–101. doi:10.1080/034687501750211127. ISSN 0346-8755. S2CID 143718697.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Abildgren, Kim (2010). "Consumer prices in Denmark 1502–2007". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 58 (1): 2–24. doi:10.1080/03585520903298184. ISSN 0358-5522. S2CID 154566198.

- ^ Glenthøj, Rasmus; Ottosen, Morten Nordhagen (2014). Experiences of War and Nationality in Denmark and Norway, 1807–1815. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9781137313898. ISBN 978-1-349-33786-6.

- ^ a b c d e Abildgren, K (2014). "Danmarks Nationalbank 1818-2018" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e Marcher, M (24 February 2012). "Economic Policy Reforms 2012 (Summary in Danish)". Economic Policy Reforms. doi:10.1787/growth-2012-sum-da. ISBN 9789264168251. ISSN 1813-2723.

- ^ a b c Chalcraft, Tony (20 March 2017). "Historical Dictionary of Denmark (3rd edition)RR 2017/089 Historical Dictionary of Denmark (3rd edition) Alastair H. Thomas Rowman & Littlefield Lanham, MD and London 2016 Liv + 649 pp. ISBN 978 1 4422 6464 9 (print); ISBN 978 1 4422 6465 6 (e-book) £95 $145 Historical Dictionaries of Europe". Reference Reviews. 31 (3): 34–35. doi:10.1108/rr-02-2017-0028. ISSN 0950-4125.

- ^ Kulsrud, Carl J. (1938). "The Seizure of the Danish Fleet, 1807: The Background". The American Journal of International Law. 32 (2): 280–311. doi:10.2307/2190974. JSTOR 2190974. S2CID 147490058.

- ^ a b c d e f Bregnsbo, Michael (27 May 2014). "The motives behind the foreign political decisions of Frederick VI during the Napoleonic Wars". Scandinavian Journal of History. 39 (3): 335–352. doi:10.1080/03468755.2014.907197. ISSN 0346-8755. S2CID 144295510.

- ^ Cronin, Kieran (19 January 2010). "Historical Dictionary of Norway201048Jan Sjåvik. Historical Dictionary of Norway. Lanham, MD and Plymouth: Scarecrow Press 2008. xxvii+269 pp., ISBN: 978 0 8108 5753 7 £53/$80 Historical Dictionaries of Europe, No. 62". Reference Reviews. 24 (1): 63–64. doi:10.1108/09504121011012201. ISSN 0950-4125.

- ^ Weibull, Jörgen (1990). "The Treaty of Kiel and its political and military background". Scandinavian Journal of History. 15 (3–4): 291–301. doi:10.1080/03468759008579206. ISSN 0346-8755.

- ^ Berg, Roald (27 May 2014). "Denmark, Norway and Sweden in 1814: a geopolitical and contemporary perspective". Scandinavian Journal of History. 39 (3): 265–286. doi:10.1080/03468755.2013.876929. ISSN 0346-8755. S2CID 145153702.

- ^ Redvaldsen, David (3 July 2014). "Great Britain and the Norwegian constitution of 1814". Parliaments, Estates and Representation. 34 (2): 182–202. doi:10.1080/02606755.2014.946828. ISSN 0260-6755.

- ^ Jensen, Mette Frisk (21 December 2017). "Statebuilding, Establishing Rule of Law and Fighting Corruption in Denmark, 1660–1900". Oxford Scholarship Online. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198809975.003.0014.

- ^ "The Peace Treaty of Kiel". www.kongehuset.no (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "History in Denmark | Frommer's". www.frommers.com. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ a b Østergård, Uffe (2004). "The Danish Path to Modernity". Thesis Eleven. 77 (1): 25–43. doi:10.1177/0725513604042658. ISSN 0725-5136. S2CID 143554261.

- ^ Ruppenthal, Roland (1943). "Denmark and the Continental System". The Journal of Modern History. 15 (1): 7–23. doi:10.1086/236690. ISSN 0022-2801. JSTOR 1871504. S2CID 144277174.

- ^ Khan, Mehreen (20 March 2017). "Denmark rids itself of foreign debt for first time in 183 years". www.ft.com. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Grab, Alexander (31 March 2010). "Review: Charles Esdaile, Napoleon's Wars. An International History, 1803—1815, Penguin: London, 2008; 656 pp., 8 maps, 27 illus.; 9780141014203, £14.99 (pbk)". European History Quarterly. 40 (2): 322–323. doi:10.1177/02656914100400020618. ISSN 0265-6914. S2CID 143748144.

- ^ a b c Jensen, Mette Frisk (21 December 2017). "Statebuilding, Establishing Rule of Law and Fighting Corruption in Denmark, 1660–1900". Oxford Scholarship Online. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198809975.003.0014.

- ^ Danmarks Nationalbank. "Danmarks Nationalbank 2018-2018". Retrieved 2 June 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gutek, Gerald L.; Stabler, Ernest (1988). "Founders: Innovators in Education, 1830-1980". History of Education Quarterly. 28 (2): 284. doi:10.2307/368500. ISSN 0018-2680. JSTOR 368500. S2CID 143599853.