Indo-Aryan migrations

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Indo-Aryan migrations[note 1] were the migrations into the Indian subcontinent of Indo-Aryan peoples, an ethnolinguistic group that spoke Indo-Aryan languages. These are the predominant languages of today's Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, North India, Eastern Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

Indo-Aryan migration into the region, from Central Asia, is considered to have started after 2000 BCE as a slow diffusion during the Late Harappan period and led to a language shift in the northern Indian subcontinent. Several hundred years later, the Iranian languages were brought into the Iranian plateau by the Iranians, who were closely related to the Indo-Aryans.

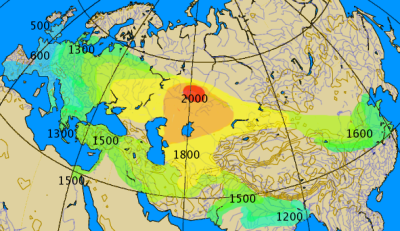

The Proto-Indo-Iranian culture, which gave rise to the Indo-Aryans and Iranians, developed on the Central Asian steppes north of the Caspian Sea as the Sintashta culture (c. 2200-1900 BCE),[2] in present-day Russia and Kazakhstan, and developed further as the Andronovo culture (2000–1450 BCE).[3][4]

The Indo-Aryans split off sometime between 2000 BCE and 1600 BCE from the Indo-Iranians,[5] and migrated southwards to the Bactria–Margiana culture (BMAC), from which they borrowed some of their distinctive religious beliefs and practices.[6] From the BMAC, the Indo-Aryans migrated into northern Syria and, possibly in multiple waves, into the Punjab (northern Pakistan and India), while the Iranians could have reached western Iran before 1300 BCE,[7] both bringing with them the Indo-Iranian languages.

Migration by an Indo-European-speaking people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland.

This linguistic argument of this theory is supported by archaeological, anthropological, genetic, literary and ecological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetic puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. Ecological studies reveal that in the second millennium BCE widespread aridization led to water shortages and ecological changes in both the Eurasian steppes and the Indian subcontinent,[web 1] causing the collapse of sedentary urban cultures in south central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India, and triggering large-scale migrations, resulting in the merger of migrating peoples with the post-urban cultures.[web 1]

The Indo-Aryan migrations started sometime in the period from approximately 2000 to 1600 BCE,[5] after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. It was part of the diffusion of Indo-European languages from the proto-Indo-European homeland at the Pontic–Caspian steppe, a large area of grasslands in far Eastern Europe, which started in the 5th to 4th millennia BCE, and the Indo-European migrations out of the Eurasian Steppes, which started approximately in 2000 BCE.[1][8]

These Indo-Aryan speaking people were united by shared cultural norms and language, referred to as ārya, "noble". Diffusion of this culture and language took place by patron-client systems, which allowed for the absorption and acculturation of other groups into this culture, and explains the strong influence on other cultures with which it interacted.

Fundamentals

– Center: Steppe cultures

1 (black): Anatolian languages (archaic PIE)

2 (black): Afanasievo culture (early PIE)

3 (black) Yamnaya culture expansion (Pontic-Caspian steppe, Danube Valley) (late PIE)

4A (black): Western Corded Ware

4B-C (blue & dark blue): Bell Beaker; adopted by Indo-European speakers

5A-B (red): Eastern Corded ware

5C (red): Sintashta (proto-Indo-Iranian)

6 (magenta): Andronovo

7A (purple): Indo-Aryans (Mittani)

7B (purple): Indo-Aryans (India)

[NN] (dark yellow): proto-Balto-Slavic

8 (grey): Greek

9 (yellow):Iranians

– [not drawn]: Armenian, expanding from western steppe

The Indo-Aryan migration theory is part of a larger theoretical framework. This framework explains the similarities between a wide range of contemporary and ancient languages. It combines linguistic, archaeological and anthropological research.[9][10] This provides an overview of the development of Indo-European languages, and the spread of these Indo-European languages by migration and acculturation.[10]

Linguistics: relationships between languages

The linguistic part traces the connections between the various Indo-European languages, and reconstructs the proto-Indo-European language. This is possible because the processes that change languages are not random, but follow strict patterns. Sound shifts, the changing of vowels and consonants, are especially important, although grammar (especially morphology) and the lexicon (vocabulary) may also be significant. Historical-comparative linguistics thus makes it possible to see great similarities between related languages which at first sight might seem very different.[10][11] Various characteristics of the Indo-European languages argue against an Indian origin of these languages, and point to a steppe origin.[11]

Archaeology: migrations from the steppe Urheimat

The archaeological part posits an "Urheimat" on the Pontic steppes, which developed after the introduction of cattle on the steppes around 5,200 BCE.[10] This introduction marked the change from foragist to pastoralist cultures, and the development of a hierarchical social system with chieftains, patron-client systems, and the exchange of goods and gifts.[10] The oldest nucleus may have been the Samara culture (late 6th and early 5th millennium BCE), at a bend in the Volga.

A wider "horizon" developed, called the Kurgan culture by Marija Gimbutas in the 1950s. She included several cultures in this "Kurgan Culture", including the Samara culture and the Yamna culture, although the Yamna culture (36th–23rd centuries BCE), also called "Pit Grave Culture", may more aptly be called the "nucleus" of the proto-Indo-European language.[10] From this area, which already included various subcultures, Indo-European languages spread west, south and east starting around 4,000 BCE.[12] These languages may have been carried by small groups of males, with patron-client systems which allowed for the inclusion of other groups into their cultural system.[10]

Eastward emerged the Sintashta culture (2200–1900 BCE), where common Indo-Iranian was spoken.[13] Out of the Sintashta culture developed the Andronovo culture (2000–1450 BCE), which interacted with the Bactria-Margiana culture (2250–1700 BCE). This interaction further shaped the Indo-Iranians, which split at sometime between 2000 and 1600 BCE into the Indo-Aryans and the Iranians.[5] The Indo-Aryans migrated to the Levant and South Asia.[14] The migration into northern India was not a large-scale immigration, but may have consisted of small groups[15][note 2] which were genetically diverse.[clarification needed] Their culture and language spread by the same mechanisms of acculturalisation, and the absorption of other groups into their patron-client system.[10]

Anthropology: elite recruitment and language shift

Indo-European languages probably spread through language shifts.[17][18][19] Small groups can change a larger cultural area,[20][10] and elite male dominance by small groups may have led to a language shift in northern India.[21][22][23]

David Anthony, in his "revised Steppe hypothesis"[24] notes that the spread of the Indo-European languages probably did not happen through "chain-type folk migrations", but by the introduction of these languages by ritual and political elites, which were emulated by large groups of people,[25][note 3] a process which he calls "elite recruitment".[26]

According to Parpola, local elites joined "small but powerful groups" of Indo-European speaking migrants.[17] These migrants had an attractive social system and good weapons, and luxury goods which marked their status and power. Joining these groups was attractive for local leaders, since it strengthened their position, and gave them additional advantages.[27] These new members were further incorporated by matrimonial alliances.[28][18]

According to Joseph Salmons, language shift is facilitated by "dislocation" of language communities, in which the elite is taken over.[29] According to Salmons, this change is facilitated by "systematic changes in community structure", in which a local community becomes incorporated in a larger social structure.[29][note 4]

Genetics: ancient ancestry and multiple gene flows

The Indo-Aryan migrations form part of a complex genetic puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population, including various waves of admixture and language shift. Studies indicate north and south Indians share a common maternal ancestry.[34][35][36][37] A series of studies show that the Indian subcontinent harbours two major ancestral components,[32][31][33] namely the Ancestral North Indians (ANI) which is "genetically close to Middle Easterners, Central Asians, and Europeans", and the Ancestral South Indians (ASI) which is clearly distinct from ANI.[32][note 5] These two groups mixed in India between 4,200 and 1,900 years ago (2200 BCE – 100 CE), after which a shift to endogamy took place,[33] possibly by the enforcement of "social values and norms" during the Gupta Empire.[39][when?]

Moorjani et al. (2013) describe three scenarios regarding the bringing together of the two groups: migrations before the development of agriculture before 8,000–9,000 years before present (BP); migration of western Asian[note 6] people together with the spread of agriculture, maybe up to 4,600 years BP; migrations of western Eurasians from 3,000 to 4,000 years BP.[40]

While Reich notes that the onset of admixture coincides with the arrival of Indo-European language,[web 2] according to Moorjani et al. (2013) these groups were present "unmixed" in India before the Indo-Aryan migrations.[33] Gallego Romero et al. (2011) propose that the ANI component came from Iran and the Middle East,[42] less than 10,000 years ago,[web 3][note 7] while according to Lazaridis et al. (2016) ANI is a mix of "early farmers of western Iran" and "people of the Bronze Age Eurasian steppe".[43] Several studies also show traces of later influxes of maternal genetic material[34][web 4] and of paternal genetic material related to ANI and possibly the Indo-Europeans.[32][44][45] While others have analysed the hereditary distribution of lactose intolerance, and specifically the presence of the -13910T lactase persistence mutation, found in Europe and Central Asia, across South Asia.[46][47][41]

Literary research: similarities, geography, and references to migration

The oldest known inscribed Indo-Iranian words, and particularly invocations of the Indo-Aryan deities, date to mid second millennia BCE, as loan words in Hurrian treaties of the Mitanni kingdom, of present-day northern Syria.[48][49]

The religious practices depicted in the Rigveda and those depicted in the Avesta, the central religious text of Zoroastrianism, show similarities.[49] Some of the references to the Sarasvati in the Rigveda refer to the Ghaggar-Hakra River,[50] while the Afghan river Haraxvaiti/Harauvati Helmand is sometimes quoted as the locus of the early Rigvedic river.[51][needs context] The Rigveda does not explicitly refer to an external homeland[52] or to a migration,[53] but later Vedic and Puranic texts do show the movement into the Gangetic plains. A number of Indologists and historians offering the Baudhayana Shrauta Sutra, verse 18.44:397.9, as explicit recorded evidence of a migration:[54][55][56][57]

Then, there is the following direct statement contained in (the admittedly much later) BSS [Baudhāyana Śrauta Sūtra] 18.44:397.9 sqq which has once again been overlooked, not having been translated yet: "Ayu went eastwards. His (people) are the Kuru Panchala and the Kasi-Videha. This is the Ayava (migration). (His other people) stayed at home. His people are the Gandhari, Parsu and Aratta. This is the Amavasava (group)" (Witzel 1989: 235).[58]

Ecological studies: widespread drought, urban collapse, and pastoral migrations

Climate change and drought may have triggered both the initial dispersal of Indo-European speakers, and the migration of Indo-Europeans from the steppes in south central Asia and India.[59][60]

Around 4200–4100 BCE a climate change occurred, manifesting in colder winters in Europe.[61] Steppe herders, archaic Proto-Indo-European speakers, spread into the lower Danube valley about 4200–4000 BCE, either causing or taking advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.[62]

The Yamna horizon was an adaptation to a climate change which occurred between 3500 and 3000 BCE, in which the steppes became drier and cooler. Herds needed to be moved frequently to feed them sufficiently, and the use of wagons and horse-back riding made this possible, leading to "a new, more mobile form of pastoralism".[63]

In the third millennium BCE widespread aridification led to water shortages and ecological changes in both the Eurasian steppes and the Indian subcontinent.[web 1][60] On the steppes, humidification led to a change of vegetation, triggering "higher mobility and transition to nomadic cattle breeding".[60][note 8][63][note 9] Water shortage also had a strong impact in the Indian subcontinent, "causing the collapse of sedentary urban cultures in south central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India, and triggering large-scale migrations".[web 1]

Development of the theory

Similarities between Sanskrit, Persian, Greek

In the 16th century, European visitors to India became aware of similarities between Indian and European languages[64] and as early as 1653 Van Boxhorn had published a proposal for a proto-language ("Scythian") for Germanic, Romance, Greek, Baltic, Slavic, Celtic, Iranian, and (incorrectly) Turkish.[65]

In a memoir sent to the French Academy of Sciences in 1767 Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux, a French Jesuit who spent all his life in India, had specifically demonstrated the existing analogy between Sanskrit and European languages.[66][note 10]

In 1786 William Jones, a judge in the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William, Calcutta, linguist, and classics scholar, on studying Sanskrit, postulated, in his Third Anniversary Discourse to the Asiatic Society, a proto-language uniting Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, Gothic and Celtic languages, but in many ways his work was less accurate than his predecessors', as he erroneously included Egyptian, Japanese and Chinese in the Indo-European languages, while omitting Hindustani[65] and Slavic:[67][68]

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists: there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanskrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family, if this were the place for discussing any question concerning the antiquities of Persia.[69][web 5]

Jones concluded that all these languages originated from the same source.[69]

Homeland

Scholars assume a homeland either in central Asia or in Western Asia, and Sanskrit must in this case have reached India by a language transfer from west to east.[70][71] In 19th century Indo-European studies, the language of the Rigveda was the most archaic Indo-European language known to scholars, indeed the only records of Indo-European that could reasonably claim to date to the Bronze Age. This primacy of Sanskrit inspired scholars such as Friedrich Schlegel, to assume that the locus of the proto-Indo-European homeland had been in India, with the other dialects spread to the west by historical migration. [70][71]

With the 20th-century discovery of Bronze-Age attestations of Indo-European (Anatolian, Mycenaean Greek), Vedic Sanskrit lost its special status as the most archaic Indo-European language known.[70][71]

Aryan "race"

In the 1850s Max Müller introduced the notion of two Aryan races, a western and an eastern one, who migrated from the Caucasus into Europe and India respectively. Müller dichotomized the two groups, ascribing greater prominence and value to the western branch. Nevertheless, this "eastern branch of the Aryan race was more powerful than the indigenous eastern natives, who were easy to conquer".[72]

Herbert Hope Risley expanded on Müller's two-race Indo-European speaking Aryan invasion theory, concluding that the caste system was a remnant of the Indo-Aryans domination of the native Dravidians, with observable variations in phenotypes between hereditary race-based castes.[73][74] Thomas Trautmann explains that Risley "found a direct relation between the proportion of Aryan blood and the nasal index, along a gradient from the highest castes to the lowest. This assimilation of caste to race proved very influential."[75]

Müller's work contributed to the developing interest in Aryan culture, which often set Indo-European ('Aryan') traditions in opposition to Semitic religions. He was "deeply saddened by the fact that these classifications later came to be expressed in racist terms", as this was far from his intention.[76][note 11] For Müller the discovery of common Indian and European ancestry was a powerful argument against racism, arguing that "an ethnologist who speaks of Aryan race, Aryan blood, Aryan eyes and hair, is as great a sinner as a linguist who speaks of a dolichocephalic dictionary or a brachycephalic grammar" and that "the blackest Hindus represent an earlier stage of Aryan speech and thought than the fairest Scandinavians".[77] In his later work, Max Müller took great care to limit the use of the term "Aryan" to a strictly linguistic one.[78]

"Aryan invasion"

The excavation of the Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and Lothal sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) in the 1920,[79] showed that northern India already had an advanced culture when the Indo-Aryans migrated into the area. The theory changed from a migration of advanced Aryans towards a primitive aboriginal population, to a migration of nomadic people into an advanced urban civilization, comparable to the Germanic migrations during the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, or the Kassite invasion of Babylonia.[80]

This possibility was for a short time seen as a hostile invasion into northern India. The decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation at precisely the period in history in which the Indo-Aryan migrations probably took place, seemed to provide independent support of such an invasion. This argument was proposed by the mid-20th century archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, who interpreted the presence of many unburied corpses found in the top levels of Mohenjo-daro as the victims of conquest wars, and who famously stated that the god "Indra stands accused" of the destruction of the Civilisation.[80]

This position was discarded after finding no evidence of wars. The skeletons were found to be hasty interments, not massacred victims.[80] Wheeler himself also nuanced this interpretation in later publications, stating "This is a possibility, but it can't be proven, and it may not be correct."[81] Wheeler further notes that the unburied corpses may indicate an event in the final phase of human occupation of Mohenjo-Daro, and that thereafter the place was uninhabited, but that the decay of Mohenjo-Daro has to be ascribed to structural causes such as salinisation.[82]

Nevertheless, although 'invasion' was discredited, critics of the Indo-Aryan Migration theory continue to present the theory as an "Aryan Invasion Theory",[1][83][note 12] presenting it as a racist and colonialist discourse:

The theory of an immigration of IA speaking Arya ("Aryan invasion") is simply seen as a means of British policy to justify their own intrusion into India and their subsequent colonial rule: in both cases, a "white race" was seen as subduing the local darker colored population.[1]

Aryan migration

In the later 20th century, ideas were refined along with data accrual, and migration and acculturation were seen as the methods whereby Indo-Aryans and their language and culture spread into northwest India around 1500 BCE. The term "invasion" is only being used nowadays by opponents[who?] of the Indo-Aryan Migration theory.[1][83] Michael Witzel:

...it has been supplanted by much more sophisticated models over the past few decades [...] philologists first, and archaeologists somewhat later, noticed certain inconsistencies in the older theory and tried to find new explanations, a new version of the immigration theories.[1][note 13]

The changed approach was in line with newly developed thinking about language transfer in general, such as the migration of the Greeks into Greece (between 2100 and 1600 BCE) and their adoption of a syllabic script, Linear B, from the pre-existing Linear A, with the purpose of writing Mycenaean Greek, or the Indo-Europeanization of Western Europe (in stages between 2200 and 1300 BCE).

Future directions

This section needs to be updated. (May 2017) |

Mallory notes that with the development and the growing sophistication of the knowledge on the Indo-European migrations and their purported homeland, new questions arise, and that "it is evident that we still have a very long way to go."[84] One of those questions is the origin of the shared agricultural vocabulary, and the earliest dates for agriculturalism in areas settled by the Indo-Europeans. Those dates seem to be too late to account for the shared vocabulary, and raise the question what their origin is.[85]

Linguistics: relationships between languages

Linguistic research traces the connections between the various Indo-European languages, and reconstructs proto-Indo-European. Accumulated linguistic evidence points to the Indo-Aryan languages as intrusive into the Indian subcontinent, some time in the 2nd millennium BCE.[86][87][88][89] The language of the Rigveda, the earliest stratum of Vedic Sanskrit, is assigned to about 1500–1200 BCE.[48]

Comparative method

Connections between languages can be traced because the processes that change languages are not random, but follow strict patterns. Especially sound shifts, the changing of vowels and consonants, are important, although grammar (especially morphology) and the lexicon (vocabulary) may also be significant. Historical-comparative linguistics thus makes it possible to see great similarities between languages which at first sight might seem very different.[10]

Linguistics use the comparative method to study the development of languages by performing a feature-by-feature comparison of two or more languages with common descent from a shared ancestor, as opposed to the method of internal reconstruction, which analyses the internal development of a single language over time.[90] Ordinarily both methods are used together to reconstruct prehistoric phases of languages, to fill in gaps in the historical record of a language, to discover the development of phonological, morphological, and other linguistic systems, and to confirm or refute hypothesized relationships between languages.[citation needed]

The comparative method aims to prove that two or more historically attested languages are descended from a single proto-language by comparing lists of cognate terms. From them, regular sound correspondences between the languages are established, and a sequence of regular sound changes can then be postulated, which allows the proto-language to be reconstructed. Relation is deemed certain only if at least a partial reconstruction of the common ancestor is feasible, and if regular sound correspondences can be established with chance similarities ruled out.[citation needed]

The comparative method was developed over the 19th century. Key contributions were made by the Danish scholars Rasmus Rask and Karl Verner and the German scholar Jacob Grimm. The first linguist to offer reconstructed forms from a proto-language was August Schleicher, in his Compendium der vergleichenden Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen, originally published in 1861.[91]

Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the linguistic reconstruction of the common ancestor of the Indo-European languages. August Schleicher's 1861 reconstruction of PIE was the first proposed proto-language to be accepted by modern linguists.[92] More work has gone into reconstructing it than any other proto-language, and it is by far the best understood among all proto-languages of its age. During the 19th century, the vast majority of linguistic work was devoted to reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European or its daughter proto-languages such as Proto-Germanic, and most of the current techniques of linguistic reconstruction in historical linguistics (e.g., the comparative method and the method of internal reconstruction) were developed as a result.[93]

PIE must have been spoken as a single language or a group of related dialects (before divergence began), though estimates of when this was by different authorities can vary massively, from the 7th millennium BCE to the second.[94] A number of hypotheses have been proposed for the origin and spread of the language, the most popular among linguists being the Kurgan hypothesis, which postulates an origin in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of Eastern Europe in the 5th or 4th millennia BCE.[95] Features of the culture of the speakers of PIE, known as Proto-Indo-Europeans, have also been reconstructed based on the shared vocabulary of the early attested Indo-European languages.[95]

As mentioned above, the existence of PIE was first postulated in the 18th century by Sir William Jones, who observed the similarities between Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, and Latin. By the early 20th century, well-defined descriptions of PIE had been developed that are still accepted today (with some refinements).[92] The largest developments of the 20th century were the discovery of the Anatolian and Tocharian languages and the acceptance of the laryngeal theory. The Anatolian languages have also spurred a major re-evaluation of theories concerning the development of various shared Indo-European language features and the extent to which these features were present in PIE itself.[citation needed] Relationships to other language families, including the Uralic languages, have been proposed but remain controversial.[citation needed]

PIE is thought to have had a complex system of morphology that included inflectional suffixes as well as ablaut (vowel alterations, as preserved in English sing, sang, sung). Nouns and verbs had complex systems of declension and conjugation respectively.[citation needed]

Arguments against an Indian origin of proto-Indo-European

Diversity

According to the linguistic center of gravity principle, the most likely point of origin of a language family is in the area of its greatest diversity.[96][note 14] By this criterion, Northern India, home to only a single branch of the Indo-European language family (i.e., Indo-Aryan), is an exceedingly unlikely candidate for the Indo-European homeland, compared to Central-Eastern Europe, for example, which is home to the Italic, Venetic, Illyrian, Albanian, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Thracian and Greek branches of Indo-European.[97]

Both mainstream Urheimat solutions locate the Proto-Indo-European homeland in the vicinity of the Black Sea.[98]

Dialectal variation

This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (August 2020) |

It has been recognized since the mid-19th century, beginning with Schmidt and Schuchardt, that a binary tree model cannot capture all linguistic alignments; certain areal features cut across language groups and are better explained through a model treating linguistic change like waves rippling out through a pond. This is true of the Indo-European languages as well. Various features originated and spread while Proto-Indo-European was still a dialect continuum.[99] These features sometimes cut across sub-families: for instance, the instrumental, dative and ablative plurals in Germanic and Balto-Slavic feature endings beginning with -m-, rather than the usual -*bh-, e.g. Gothic dative plural sunum 'to the sons' and Old Church Slavonic instrumental plural synъ-mi 'with sons',[100] despite the fact that the Germanic languages are centum, while Balto-Slavic languages are satem.

The strong correspondence between the dialectal relationships of the Indo-European languages and their actual geographical arrangement in their earliest attested forms makes an Indian origin, as suggested by the Out of India Theory, unlikely.[101]

Substrate influence

Already in the 1870s the Neogrammarians[who?] realised that the Greek/Latin vocalism couldn't be explained on the basis of the Sanskrit one, and therefore must be more original.[citation needed] The Indo-Iranian and Uralic languages influenced each other, with the Finno-Ugric languages containing Indo-European loan words. A telling example is the Finnish word vasara, "hammer", which is related to vajra, the weapon of Indra. Since the Finno-Ugric homeland was located in the northern forest zone in northern Europe, the contacts must have taken place – in line with the placement of the proto-Indo-European homeland at the Pontic-Caspian steppes – between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.[web 1]

Dravidian and other South Asian languages share with Indo-Aryan a number of syntactical and morphological features that are alien to other Indo-European languages, including even its closest relative, Old Iranian. Phonologically, there is the introduction of retroflexes, which alternate with dentals in Indo-Aryan; morphologically there are the gerunds; and syntactically there is the use of a quotative marker (iti).[note 15] These are taken as evidence of substratum influence.

It has been argued [by whom?] that Dravidian influenced Indic through "shift", whereby native Dravidian speakers learned and adopted Indic languages.[citation needed] The presence of Dravidian structural features in Old Indo-Aryan is thus plausibly explained, that the majority of early Old Indo-Aryan speakers had a Dravidian mother tongue which they gradually abandoned.[102] Even though the innovative traits in Indic could be explained by multiple internal explanations, early Dravidian influence is the only explanation that can account for all of the innovations at once – it becomes a question of explanatory parsimony; moreover, early Dravidian influence accounts for several of the innovative traits in Indic better than any internal explanation that has been proposed.[103]

A pre-Indo-European linguistic substratum in the Indian subcontinent would be a good reason to exclude India as a potential Indo-European homeland.[104] However, several linguists[who?], all of whom accept the external origin of the Aryan languages on other grounds, are still open to considering the evidence as internal developments rather than the result of substrate influences,[105] or as adstratum effects.[106]

Archaeology: migrations from the steppe Urheimat

| ||

|

The Sintashta, Andronovo, Bactria-Margiana and Yaz cultures have been associated with Indo-Iranian migrations in Central Asia.[107] The Gandhara Grave, Cemetery H, Copper Hoard and Painted Grey Ware cultures are candidates for subsequent cultures within South Asia associated with Indo-Aryan movements.[needs context] The decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation predates the Indo-Aryan migrations, but archeological data show a cultural continuity in the archeological record. Together with the presence of Dravidian loanwords in the Rigveda, this[clarification needed] argues in favor of an interaction between post-Harappan and Indo-Aryan cultures.[108]

Stages of migrations

About 6,000 years ago the Indo-Europeans started to spread out from their proto-Indo-European homeland in Central Eurasia, between the southern Ural Mountains, the North Caucasus, and the Black Sea.[12] About 4,000 years ago Indo-European speaking peoples started to migrate out of the Eurasian steppes.[109][note 16]

Diffusion from the "Urheimat"

Scholars regard the middle Volga, which was the location of the Samara culture (late 6th and early 5th millennium BCE), and the Yamna culture, to be the "Urheimat" of the Indo-Europeans, as described by the Kurgan hypothesis. From this "Urheimat", Indo-European languages spread throughout the Eurasian steppes between c. 4,500 and 2,500 BCE, forming the Yamna culture.

Sequence of migrations

David Anthony gives an elaborate overview of the sequence of migrations.

The oldest attested Indo-European language is Hittite, which belongs to the oldest written Indo-European languages, the Anatolian branch.[110] Although the Hittites are placed in the 2nd millennium BCE,[111] the Anatolian branch seems to predate Proto-Indo-European, and may have developed from an older Pre-Proto-Indo-European ancestor.[112] If it separated from Proto-Indo-European, it is likely to have done so between 4500 and 3500 BCE.[113]

A migration of archaic Proto-Indo-European speaking steppe herders into the lower Danube valley took place about 4200–4000 BCE, either causing or taking advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.[62]

According to Mallory and Adams, migrations southward founded the Maykop culture (c. 3500–2500 BCE),[114] and eastward the Afanasevo culture (c. 3500–2500 BCE),[115] which developed into the Tocharians (c. 3700–3300 BCE).[116]

According to Anthony, between 3100 and 2800/2600 BCE, a real folk migration of Proto-Indo-European speakers from the Yamna-culture took place toward the west, into the Danube Valley.[117] These migrations probably split off Pre-Italic, Pre-Celtic and Pre-Germanic from Proto-Indo-European.[118] According to Anthony, this was followed by a movement north, which split away Baltic-Slavic c. 2800 BCE.[119] Pre-Armenian split off at the same time.[120] According to Parpola, this migration is related to the appearance of Indo-European speakers from Europe in Anatolia, and the appearance of Hittite.[121]

The Corded Ware culture in Middle Europe ( 2900–2450/2350 cal. BCE),[122] has been associated with some of the languages in the Indo-European family. According to Haak et al. (2015) a massive migration took place from the Eurasian steppes to Central Europe.

This migration is closely associated with the Corded Ware culture.[123][web 6][web 7]

The Indo-Iranian language and culture emerged in the Sintashta culture (c. 2050–1900 BCE),[124] where the chariot was invented.[10] Allentoft et al. (2015) found close autosomal genetic relationship between peoples of Corded Ware culture and Sintashta culture, which "suggests similar genetic sources of the two", and may imply that "the Sintashta derives directly from an eastward migration of Corded Ware peoples".[125]

The Indo-Iranian language and culture was further developed in the Andronovo culture (c. 2000–1450 BCE), and influenced by the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (c. 2250–1700 BCE). The Indo-Aryans split off sometime around 2000–1600 BCE from the Iranians,[5] after which Indo-Aryan groups are thought to have moved to the Levant (Mitanni), the northern Indian subcontinent (Vedic people, c. 1500 BCE), and China (Wusun).[14] Thereafter the Iranians migrated into Iran.[14]

Central Asia: formation of Indo-Iranians

Indo-Iranian peoples are a grouping of ethnic groups consisting of the Indo-Aryan, Iranian and Nuristani peoples; that is, speakers of Indo-Iranian languages.

The Proto-Indo-Iranians are commonly identified with the Andronovo culture,[107] that flourished c. 2000–1450 BCE in an area of the Eurasian Steppe that borders the Ural River on the west, the Tian Shan on the east. The older Sintashta culture (2200–1900), formerly included within the Andronovo culture, is now considered separately, but regarded as its predecessor, and accepted as part of the wider Andronovo horizon.

The Indo-Aryan migration was part of the Indo-Iranian migrations from the Andronovo culture into Anatolia, Iran and South Asia.[6]

Sintashta-Petrovka culture

The Sintashta culture, also known as the Sintashta-Petrovka culture[126] or Sintashta-Arkaim culture,[127] is a Bronze Age archaeological culture of the northern Eurasian Steppe on the borders of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, dated to the period 2200–1900 BCE.[124] The Sintashta culture is probably the archaeological manifestation of the Indo-Iranian language group.[128]

The Sintashta culture emerged from the interaction of two antecedent cultures. Its immediate predecessor in the Ural-Tobol steppe was the Poltavka culture, an offshoot of the cattle-herding Yamnaya horizon that moved east into the region between 2800 and 2600 BCE.[129] Several Sintashta towns were built over older Poltovka settlements or close to Poltovka cemeteries, and Poltovka motifs are common on Sintashta pottery. Sintashta material culture also shows the influence of the late Abashevo culture, a collection of Corded Ware settlements in the forest steppe zone north of the Sintashta region that were also predominantly pastoralist.[130] Allentoft et al. (2015) also found close autosomal genetic relationship between peoples of Corded Ware culture and Sintashta culture.[125]

The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials, and the culture is considered a strong candidate for the origin of the technology, which spread throughout the Old World and played an important role in ancient warfare.[131] Sintashta settlements are also remarkable for the intensity of copper mining and bronze metallurgy carried out there, which is unusual for a steppe culture.[132]

Because of the difficulty of identifying the remains of Sintashta sites beneath those of later settlements, the culture was only recently distinguished from the Andronovo culture.[127] It is now recognised as a separate entity forming part of the 'Andronovo horizon'.[126]

Andronovo culture

The Andronovo culture is a collection of similar local Bronze Age Indo-Iranian cultures that flourished c. 2000–1450 BC in western Siberia and the central Eurasian Steppe.[3][133] It is probably better termed an archaeological complex or archaeological horizon. The name derives from the village of Andronovo (55°53′N 55°42′E / 55.883°N 55.700°E), where in 1914, several graves were discovered, with skeletons in crouched positions, buried with richly decorated pottery. The older Sintashta culture (2050–1900 BCE), formerly included within the Andronovo culture, is now considered[by whom?] separately, but regarded as its predecessor, and accepted as part of the wider Andronovo horizon.

Currently only two sub-cultures are considered as part of Andronovo culture:

- Alakul (2000–1700 BC)[4] between Oxus (today Amu Darya), and Jaxartes, Kyzylkum desert

- Fëdorovo (2000–1450 BC)[134][4] in southern Siberia (earliest evidence of cremation and fire cult[135])

Other authors identified previously the following sub-cultures also as part of Andronovo:

- Eastern Fedorovo (1750–1500 BC)[136] in Tian Shan mountains (Northwestern Xinjiang, China), southeastern Kazakhstan, eastern Kyrgyzstan

- Alekseyevka (1200–1000 BC)[137] "final Bronze Age phase" in eastern Kazakhstan, contacts with Namazga VI in Turkmenia

The geographical extent of the culture is vast and difficult to delineate exactly. On its western fringes, it overlaps with the approximately contemporaneous, but distinct, Srubna culture in the Volga–Ural interfluvial. To the east, it reaches into the Minusinsk depression, with some sites as far west as the southern Ural Mountains,[138] overlapping with the area of the earlier Afanasevo culture.[139] Additional sites are scattered as far south as the Kopet Dag (Turkmenistan), the Pamir (Tajikistan) and the Tian Shan (Kyrgyzstan). The northern boundary vaguely corresponds to the beginning of the Taiga.[138] In the Volga basin, interaction with the Srubna culture was the most intense and prolonged, and Federovo style pottery is found as far west as Volgograd.

Towards the middle of the 2nd millennium, the Andronovo cultures begin to move intensively eastwards. They mined deposits of copper ore in the Altai Mountains and lived in villages of as many as ten sunken log cabin houses measuring up to 30m by 60m in size. Burials were made in stone cists or stone enclosures with buried timber chambers.

In other respects, the economy was pastoral, based on cattle, horses, sheep, and goats.[138] While agricultural use has been posited,[by whom?] no clear evidence has been presented.

Studies associate the Andronovo horizon with early Indo-Iranian languages, though it may have overlapped the early Uralic-speaking area at its northern fringe, including the Turkic-speaking area at its northeastern fringe.[140][141][142]

Based on its use by Indo-Aryans in Mitanni and Vedic India, its prior absence in the Near East and Harappan India, and its 19–20th century BCE attestation at the Andronovo site of Sintashta, Kuz'mina (1994) argues that the chariot corroborates the identification of Andronovo as Indo-Iranian.[143][note 17] Anthony & Vinogradov (1995) dated a chariot burial at Krivoye Lake to about 2000 BCE and a Bactria-Margiana burial that also contains a foal has recently been found, indicating further links with the steppes.[147]

Mallory acknowledges the difficulties of making a case for expansions from Andronovo to northern India, and that attempts to link the Indo-Aryans to such sites as the Beshkent and Vakhsh cultures "only gets the Indo-Iranian to Central Asia, but not as far as the seats of the Medes, Persians or Indo-Aryans". He has developed the "kulturkugel" model that has the Indo-Iranians taking over Bactria-Margiana cultural traits but preserving their language and religion[contradictory] while moving into Iran and India.[148][146] Fred Hiebert also agrees that an expansion of the BMAC into Iran and the margin of the Indus Valley is "the best candidate for an archaeological correlate of the introduction of Indo-Iranian speakers to Iran and South Asia."[146] According to Narasimhan et al. (2018), the expansion of the Andronovo culture towards the BMAC took place via the Inner Asia Mountain Corridor.[149]

Bactria-Margiana culture

The Bactria-Margiana Culture, also called "Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex", was a non-Indo-European culture which influenced the Indo-Iranians.[6] It was centered in what is nowadays northwestern Afghanistan and southern Turkmenistan.[6] Proto-Indo-Iranian arose due to this influence.[6]

The Indo-Iranians also borrowed their distinctive religious beliefs[contradictory] and practices from this culture.[6] According to Anthony, the Old Indic religion probably emerged among Indo-European immigrants in the contact zone between the Zeravshan River (present-day Uzbekistan) and (present-day) Iran.[150] It was "a syncretic mixture of old Central Asian and new Indo-European elements",[150] which borrowed "distinctive religious beliefs and practices"[6] from the Bactria–Margiana culture.[6] At least 383 non-Indo-European words were borrowed from this culture, including the god Indra and the ritual drink Soma.[151]

The characteristically Bactria-Margiana (southern Turkmenistan/northern Afghanistan) artifacts found at burials in Mehrgarh and Balochistan are explained by a movement of peoples from Central Asia to the south.[152] The Indo-Aryan tribes may have been present in the area of the BMAC from 1700 BCE at the latest (incidentally corresponding with the decline of that culture).

From the BMAC, the Indo-Aryans moved into the Indian subcontinent. According to Bryant, the Bactria-Margiana material inventory of the Mehrgarh and Baluchistan burials is "evidence of an archaeological intrusion into the subcontinent from Central Asia during the commonly accepted time frame for the arrival of the Indo-Aryans".[153][note 18]

Multiple waves of migration into northern India

According to Parpola, Indo-Aryan clans migrated into South Asia in subsequent waves.[108] This explains the diversity of views found in the Rig Veda, and may also explain the existence of various Indo-Aryan cultural complexes in the later Vedic period, namely the Vedic culture centered on the Kuru Kingdom in the heartland of Aryavarta in the western Ganges plain, and the cultural complex of Greater Magadha at the eastern Ganges plain, which gave rise to Jainism and Buddhism.[108][154][155]

Writing in 1998, Parpola postulated a first wave of immigration from as early as 1900 BCE, corresponding to the Cemetery H culture and the Copper Hoard culture, c.q. Ochre Coloured Pottery culture, and an immigration to the Punjab . 1700–1400 BCE.[156][note 19] In 2020, Parpola proposed an even earlier wave of proto-Indo-Iranian speaking people from the Sintashta culture[157] into India at c. 1900 BCE, related to the Copper Hoard Culture, followed by a pre-Rig Vedic Indo-Aryan wave of migration:[158]

It seems, then, that the earliest Aryan-speaking immigrants to South Asia, the Copper Hoard people, came with bull-drawn carts (Sanauli and Daimabad) via the BMAC and had Proto-Indo-Iranian as their language. They were, however, soon followed (and probably at least partially absorbed) by early Indo-Aryans.[159]

This pre-Rig-Vedic wave of migration by early Indo-Aryans is associated by Parpola with "the early (Ghalegay IV–V) phase of the Gandhara Grave culture" and the Atharva Veda tradition, and related to the Petrovka culture.[160] The Rig-Vedic wave followed several centuries later, "perhaps in the fourteenth century BCE", and is associated by Parpola with the Fedorovo culture.[161]

According to Kochhar there were three waves of Indo-Aryan immigration that occurred after the mature Harappan phase:[162]

- the "Murghamu" (Bactria-Margiana culture) related people who entered Balochistan at Pirak, Mehrgarh south cemetery, and other places, and later merged with the post-urban Harappans during the late Harappans Jhukar phase (2000–1800 BCE);

- the Swat IV that co-founded the Harappan Cemetery H phase in Punjab (2000–1800 BCE);

- and the Rigvedic Indo-Aryans of Swat V that later absorbed the Cemetery H people and gave rise to the Painted Grey Ware culture (PGW) (to 1400 BCE).

Gandhara grave culture and Ochre Coloured Pottery culture

The standard model[by whom?] for the entry of the Indo-European languages into India is that Indo-Aryan migrants went over the Hindu Kush, forming the Gandhara grave culture or Swat culture, in present-day Swat valley, into the headwaters of either the Indus or the Ganges (probably both). The Gandhara grave culture, which emerged c. 1600 BCE and flourished from c. 1500 BCE to 500 BCE in Gandhara, modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, is thus the most likely locus of the earliest bearers of Rigvedic culture. About 1800 BCE, there is a major cultural change in the Swat Valley with the emergence of the Gandhara grave culture. With its introduction of new ceramics, new burial rites, and the horse, the Gandhara grave culture is a major candidate for early Indo-Aryan presence. The two new burial rites—flexed inhumation in a pit and cremation burial in an urn—were, according to early Vedic literature, both practiced in early Indo-Aryan society. Horse-trappings indicate the importance of the horse to the economy of the Gandharan grave culture. Two horse burials indicate the importance of the horse in other respects. Horse burial is a custom that Gandharan grave culture has in common with Andronovo, though not within the distinctive timber-frame graves of the steppe.[163]

Parpola (2020) states:

The dramatic new discovery of cart burials dated to c. 1900 at Sinauli have been reviewed in this paper, and they support my proposal of a pre-Ṛvedic wave (now set of waves) of Aryan speakers arriving in South Asia and their making contact with the Late Harappans.[164]

Two waves of Indo-Iranian migration

The Indo-Iranian migrations took place in two waves,[165][166] belonging to the second and the third stage of Beckwith's description of the Indo-European migrations.[167] The first wave consisted of the Indo-Aryan migration into the Levant, seemingly founding the Mitanni kingdom in northern Syria[168] (c. 1600–1350 BCE),[169] and the migration south-eastward of the Vedic people, over the Hindu Kush into northern India.[170] Christopher I. Beckwith suggests that the Wusun, an Indo-European Europoid people of Inner Asia in antiquity, were also of Indo-Aryan origin.[171] The second wave is interpreted as the Iranian wave.[172]

First wave – Indo-Aryan migrations

Mittani

Mitanni (Hittite cuneiform KURURUMi-ta-an-ni), also Mittani (Mi-it-ta-ni) or Hanigalbat (Assyrian Hanigalbat, Khanigalbat cuneiform Ḫa-ni-gal-bat) or Naharin in ancient Egyptian texts was a Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria and south-east Anatolia from c. 1600 BCE – 1350 BCE.[169]

According to one hypothesis, founded by an Indo-Aryan ruling class governing a predominately Hurrian population, Mitanni came to be a regional power after the Hittite destruction of Amorite[173] Babylon and a series of ineffectual Assyrian kings created a power vacuum in Mesopotamia. At the beginning of its history, Mitanni's major rival was Egypt under the Thutmosids. However, with the ascent of the Hittite empire, Mitanni and Egypt made an alliance to protect their mutual interests from the threat of Hittite domination.[citation needed]

At the height of its power, during the 14th century BCE, Mitanni had outposts centered on its capital, Washukanni, whose location has been determined by archaeologists to be on the headwaters of the Khabur River. Their sphere of influence is shown in Hurrian place names, personal names and the spread through Syria and the Levant of a distinct pottery type. Eventually, Mitanni succumbed to Hittite and later Assyrian attacks, and was reduced to the status of a province of the Middle Assyrian Empire.[citation needed]

The earliest written evidence for an Indo-Aryan language is found not in Northwestern India and Pakistan, but in northern Syria, the location of the Mitanni kingdom.[107] The Mitanni kings took Old Indic throne names, and Old Indic technical terms were used for horse-riding and chariot-driving.[107] The Old Indic term r'ta, meaning "cosmic order and truth", the central concept of the Rigveda, was also employed in the Mitanni kingdom.[107] Old Indic gods, including Indra, were also known in the Mitanni kingdom.[174][175][176]

North-India – Vedic culture

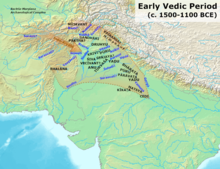

| Spread of Vedic culture |

|---|

|

Spread of Vedic-Brahmanic culture

During the Early Vedic Period (c. 1500–800 BCE[web 9]) the Indo-Aryan culture was centered in the northern Punjab, or Sapta Sindhu.[web 9] During the Later Vedic Period (c. 800–500 BCE[web 10]) the Indo-Aryan culture started to extend into the western Ganges Plain,[web 10] centering on the Vedic Kuru and Panchala area,[155] and had some influence[177] at the central Ganges Plain after 500 BCE.[web 11] Sixteen Mahajanapada developed at the Ganges Plain, of which the Kuru and Panchala became the most notable developed centers of Vedic culture, at the western Ganges Plain.[web 10][155]

The Central Ganges Plain, where Magadha gained prominence, forming the base of the Maurya Empire, was a distinct cultural area,[178] with new states arising after 500 BCE[web 11] during the so-called "Second urbanisation".[179][note 20] It was influenced by the Vedic culture,[177] but differed markedly from the Kuru-Panchala region.[178] It "was the area of the earliest known cultivation of rice in the Indian subcontinent and by 1800 BCE was the location of an advanced neolithic population associated with the sites of Chirand and Chechar".[180] In this region the Shramanic movements flourished, and Jainism and Buddhism originated.[155]

Indus Valley Civilization

The Indo-Aryan migration into the northern Punjab started shortly after the decline of the Indus Valley civilisation (IVC). According to the "Aryan Invasion Theory" this decline was caused by "invasions" of barbaric and violent Aryans who conquered the IVC. This "Aryan Invasion Theory" is not supported by the archeological and genetic data, and is not representative of the "Indo-Aryan migration theory".[citation needed]

Decline of Indus Valley Civilisation

The decline of the IVC from about 1900 BCE started before the onset of the Indo-Aryan migrations, caused by aridisation due to shifting mossoons.[181][182] A regional cultural discontinuity occurred during the second millennium BCE and many Indus Valley cities were abandoned during this period, while many new settlements began to appear in Gujarat and East Punjab and other settlements such as in the western Bahawalpur region increased in size.[citation needed]

Jim G. Shaffer and Lichtenstein contend that in the second millennium BCE considerable "location processes" took place. In the eastern Punjab 79.9% and in Gujarat 96% of sites changed settlement status. According to Shaffer & Lichtenstein,

It is evident that a major geographic population shift accompanied this 2nd millennium BCE localisation process. This shift by Harappan and, perhaps, other Indus Valley cultural mosaic groups, is the only archaeologically documented west-to-east movement of human populations in the Indian subcontinent before the first half of the first millennium B.C.[183]

Continuity of Indus Valley civilization

According to Erdosy, the ancient Harappans were not markedly different from modern populations in Northwestern India and present-day Pakistan. Craniometric data showed similarity with prehistoric peoples of the Iranian plateau and Western Asia,[note 21] although Mohenjo-daro was distinct from the other areas of the Indus Valley.[note 22][note 23]

According to Kennedy, there is no evidence of "demographic disruptions" after the decline of the Harappa culture.[185][note 24] Kenoyer notes that no biological evidence can be found for major new populations in post-Harappan communities.[186][note 25] Hemphill notes that "patterns of phonetic affinity" between Bactria and the Indus Valley Civilisation are best explained by "a pattern of long-standing, but low-level bidirectional mutual exchange".[note 26]

According to Kennedy, the Cemetery H culture "shows clear biological affinities" with the earlier population of Harappa.[187] The archaeologist Kenoyer noted that this culture "may only reflect a change in the focus of settlement organization from that which was the pattern of the earlier Harappan phase and not cultural discontinuity, urban decay, invading aliens, or site abandonment, all of which have been suggested in the past."[188] Recent excavations in 2008 at Alamgirpur, Meerut District, appeared to show an overlap between the Harappan and Painted Grey Ware culture (PGW) pottery[189] indicating cultural continuity.

Relation with Indo-Aryan migrations

According to Kenoyer, the decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation is not explained by Aryan migrations,[190][note 27] which took place after the decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Yet, according to Erdosy,

Evidence in material culture for systems collapse, abandonment of old beliefs and large-scale, if localised, population shifts in response to ecological catastrophe in the 2nd millennium B.C. must all now be related to the spread of Indo-Aryan languages.[191]

Erdosy, testing hypotheses derived from linguistic evidence against hypotheses derived from archaeological data,[192] states that there is no evidence of "invasions by a barbaric race enjoying technological and military superiority",[193] but "some support was found in the archaeological record for small-scale migrations from Central Asia to the Indian subcontinent in the late 3rd/early 2nd millennia BCE".[194] According to Erdosy, the postulated movements within Central Asia can be placed within a processional framework, replacing simplistic concepts of "diffusion", "migrations" and "invasions".[195]

Scholars have argued that the historical Vedic culture is the result of an amalgamation of the immigrating Indo-Aryans with the remnants of the indigenous civilization, such as the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture. Such remnants of IVC culture are not prominent in the Rigveda, with its focus on chariot warfare and nomadic pastoralism in stark contrast with an urban civilization.[citation needed]

Inner Asia – Wusun and Yuezhi

According to Christopher I. Beckwith the Wusun, an Indo-European Caucasian people of Inner Asia in antiquity, were also of Indo-Aryan origin.[171] From the Chinese term Wusun, Beckwith reconstructs the Old Chinese *âswin, which he compares to the Old Indic aśvin "the horsemen", the name of the Rigvedic twin equestrian gods.[171] Beckwith suggests that the Wusun were an eastern remnant of the Indo-Aryans, who had been suddenly pushed to the extremeties of the Eurasian Steppe by the Iranian peoples in the 2nd millennium BCE.[196]

The Wusun are first mentioned[when?] by Chinese sources as vassals in the Tarim Basin of the Yuezhi,[197] another Indo-European Caucasian people of possible Tocharian stock.[198][199] Around 175 BCE, the Yuezhi were utterly defeated by the Xiongnu, also former vassals of the Yuezhi.[199][200] The Yuezhi subsequently attacked the Wusun and killed their king (Kunmo Chinese: 昆莫 or Kunmi Chinese: 昆彌) Nandoumi (Chinese: 難兜靡), capturing the Ili Valley from the Saka (Scythians) shortly afterwards.[200] In return the Wusun settled in the former territories of the Yuezhi as vassals of the Xiongnu.[200][201]

The son of Nandoumi was adopted by the Xiongnu king and made leader of the Wusun.[201] Around 130 BCE he attacked and utterly defeated the Yuezhi, settling the Wusun in the Ili Valley.[201] After the Yuezhi were defeated by the Xiongnu, in the 2nd century BCE, a small group, known as the Little Yuezhi, fled to the south, while the majority migrated west to the Ili Valley, where they displaced the Sakas (Scythians). Driven from the Ili Valley shortly afterwards by the Wusun, the Yuezhi migrated to Sogdia and then Bactria, where they are often identified with the Tókharoi (Τοχάριοι) and Asii of Classical sources. They then expanded into northern Indian subcontinent, where one branch of the Yuezhi founded the Kushan Empire. The Kushan empire stretched from Turpan in the Tarim Basin to Pataliputra on the Indo-Gangetic Plain at its greatest extent, and played an important role in the development of the Silk Road and the transmission of Buddhism to China.

Soon after 130 BCE the Wusun became independent of the Xiongnu, becoming trusted vassals of the Han dynasty and powerful force in the region for centuries.[201] With the emerging steppe federations of the Rouran, the Wusun migrated into the Pamir Mountains in the 5th century CE.[200] They are last mentioned in 938 when a Wusun chieftain paid tribute to the Liao dynasty.[200]

Second wave – Iranians

The first Iranians to reach the Black Sea may have been the Cimmerians in the 8th century BCE, although their linguistic affiliation is uncertain. They were followed by the Scythians[when?], who would dominate the area, at their height, from the Carpathian Mountains in the west, to the easternmost fringes of Central Asia in the east. For most of their existence, the Scythians were based in what is modern-day Ukraine and southern European Russia. Sarmatian tribes, of whom the best known are the Roxolani (Rhoxolani), Iazyges (Jazyges) and the Alans, followed the Scythians westwards into Europe in the late centuries BCE and the 1st and 2nd centuries of the Common Era (The Migration Period). The populous Sarmatian tribe of the Massagetae, dwelling near the Caspian Sea, were known to the early rulers of Persia in the Achaemenid Period. In the east, the Scythians occupied several areas in Xinjiang, from Khotan to Tumshuq.

The Medes, Parthians and Persians begin to appear on the western Iranian Plateau from c. 800 BCE, after which they remained under Assyrian rule for several centuries, as it was with the rest of the peoples in the Near East. The Achaemenids replaced Median rule from 559 BCE. Around the first millennium of the Common Era (AD), the Kambojas, the Pashtuns and the Baloch began to settle on the eastern edge of the Iranian Plateau, on the mountainous frontier of northwestern and western Pakistan, displacing the earlier Indo-Aryans from the area.

In Central Asia, the Turkic languages have marginalized Iranian languages as a result of the Turkic migration of the early centuries CE. In Eastern Europe, Slavic and Germanic peoples assimilated and absorbed the native Iranian languages (Scythian and Sarmatian) of the region. Extant major Iranian languages are Persian, Pashto, Kurdish, and Balochi, besides numerous smaller ones.

Anthropology: elite recruitment and language shift

Elite dominance

Small groups can change a larger cultural area,[20][10] and elite male dominance by small groups may have led to a language shift in northern India.[21][22][23][note 28] Thapar notes that Indo-Aryan chiefs may have provided protection to non-Aryan agriculturalists, offering a system of patronage placing the chiefs in a superior position. This would have involved bilingualism, resulting in the adoption of Indo-Aryan languages by local populations.[202] According to Parpola, local elites joined "small but powerful groups" of Indo-European speaking migrants.[17] These migrants had an attractive social system and good weapons, and luxury goods which marked their status and power. Joining these groups was attractive for local leaders, since it strengthened their position, and gave them additional advantages.[27] These new members were further incorporated by matrimonial alliances.[28][18]

Renfrew: models of "linguistic replacement"

Basu et al. refer to Renfrew, who described four models for "linguistic replacement":[21][203]

- The demographic-subsistence model, exemplified by the process of agricultural dispersal, in which the incoming group has exploitive technologies which makes them dominant. It may lead to significant gene flow, and significant genetic changes in the population. But it may also lead to acculturalisation, in which case the technologies are taken over, but there is less change in the genetic composition of the population;

- The existence of extended trading systems which led to the development of a lingua franca, in which case some gene flow is to be expected;

- The elite dominance model, in which "a relatively small but well-organized group [...] take[s] over the system".[204] Given the small size of the elite, its genetic influence may also be small, though "preferential access to marriage partners" may result in a relatively strong influence on the gene pool. Sexual asymmetry may also be of influence: incoming elites often consist mostly of males, who have no influence on the mitochondrial DNA of the gene pool, but may influence the Y chromosomes of the gene pool;

- System collapse, in which territorial boundaries are changed, and elite dominance may appear for a while.

David Anthony: elite recruitment

David Anthony, in his "revised Steppe hypothesis"[24] notes that the spread of the Indo-European languages probably did not happen through "chain-type folk migrations", but by the introduction of these languages by ritual and political elites, which are emulated by large groups of people.[25][note 3][note 29] Anthony gives the example of the Southern Luo-speaking Acholi in northern Uganda in the 17th and 18th century, whose language spread rapidly in the 19th century.[22] Anthony notes that "Indo-European languages probably spread in a similar way among the tribal societies of prehistoric Europe", carried forward by "Indo-European chiefs" and their "ideology of political clientage".[26] Anthony notes that "elite recruitment" may be a suitable term for this system.[26][note 30]

Michael Witzel: small groups and acculturation

Michael Witzel refers to Ehret's model[note 31] "which stresses the osmosis, or a 'billiard ball', or Mallory's Kulturkugel, effect of cultural transmission".[20] According to Ehret, ethnicity and language can shift with relative ease in small societies, due to the cultural, economic and military choices made by the local population in question. The group bringing new traits may initially be small, contributing features that can be fewer in number than those of the already local culture. The emerging combined group may then initiate a recurrent, expansionist process of ethnic and language shift.[20]

Witzel notes that "arya/ārya does not mean a particular 'people' or even a particular 'racial' group but all those who had joined the tribes speaking Vedic Sanskrit and adhering to their cultural norms (such as ritual, poetry, etc.)."[207] According to Witzel, "there must have been a long period of acculturation between the local population and the 'original' immigrants speaking Indo-Aryan."[207] Witzel also notes that the speakers of Indo-Aryan and the local population must have been bilingual, speaking each other's languages and interacting with each other, before the Rg Veda was composed in the Punjab.[208]

Salmons: systematic changes in community structure

Joseph Salmons notes that Anthony presents scarce concrete evidence or arguments.[209] Salmons is critical about the notion of "prestige" as a central factor in the shift to Indo-European languages, referring to Milroy who notes that "prestige" is "a cover term for a variety of very distinct notions".[209] Instead, Milroy offers "arguments built around network structure", though Salmons also notes that Anthony includes several of those arguments, "including political and technological advantages".[209] According to Salmons, the best model is offered by Fishman,[note 32] who

... understands shift in terms of geographical, social, and cultural "dislocation" of language communities. Social dislocation, to give the most relevant example, involves "siphoning off the talented, the enterprising, the imaginative and the creative" ([Fishman] 1991: 61), and sounds strikingly like Anthony's 'recruitment' scenario.[29]

Salmons himself argues that

... systematic changes in community structure are what drive language shift, incorporating Milroy's network structures as well. The heart of the view is the quintessential element of modernization, namely a shift from local community-internal organization to regional (state or national or international, in modern settings), extra-community organizations. Shift correlates with this move from pre-dominantly "horizontal" community structures to more "vertical" ones.[29][note 4]

Genetics: ancient ancestry and multiple gene flows

India has one of the most genetically diverse populations in the world, and the history of this genetic diversity is the topic of continued research and debate. The Indo-Aryan migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population, including various waves of admixture and language shift. The genetic impact of the Indo-Aryans may have been marginal, but this is not at odds with the cultural and linguistic influence, since language shift is possible without a change in genetics.[210]

Ancestral groups

Common maternal ancestry

Sahoo et al. (2006) states that "there is general agreement that Indian caste and tribal populations share a common late Pleistocene maternal ancestry in India."

Kivisild et al. (1999) concluded that there is "an extensive deep late Pleistocene[jargon] genetic link between contemporary Europeans and Indians" via the mitochondrial DNA, that is, DNA which is inherited from the mother. According to them, the two groups split at the time of the peopling of Asia and Eurasia and before modern humans entered Europe.[34] Kivisild et al. (2000) note that "the sum of any recent (the last 15,000 years) western mtDNA gene flow to India comprises, in average, less than 10 percent of the contemporary Indian mtDNA lineages."[web 4]

Kivisild et al. (2003) and Sharma et al. (2005) note that north and south Indians share a common maternal ancestry: Kivisild et al. (2003) further note that "these results show that Indian tribal and caste populations derive largely from the same genetic heritage of Pleistocene[jargon] southern and western Asians and have received limited gene flow from external regions since the Holocene.[jargon][35]

"Ancestral North Indians" and "Ancestral South Indians"

Reich et al. (2009), in a collaborative effort between the Harvard Medical School and the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), examined the entire genomes worth 560,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), as compared to 420 SNPs in prior work. They also cross-compared them with the genomes of other regions available in the global genome database.[211] Through this study, they were able to discern two genetic groups in the majority of populations in India, which they called "Ancestral North Indians" (ANI) and "Ancestral South Indians" (ASI).[note 33] They found that the ANI genes are close to those of Middle Easterners, Central Asians and Europeans whereas the ASI genes are dissimilar to all other known populations outside India, though the indigenous Andamanese were determined to be the most closely related to the ASI population of any living group (albeit distinct from the ASI).[note 34][note 35] These two distinct groups, which had split ca. 50,000 years ago, formed the basis for the present population of India.[web 12]

The two groups mixed between 1,900 and 4,200 years ago (2200 BCE – 100 CE), where-after a shift to endogamy took place and admixture became rare.[note 36] Speaking to Fountain Ink, David Reich stated, "Prior to 4,200 years ago, there were unmixed groups in India. Sometime between 1,900 to 4,200 years ago, profound, pervasive convulsive mixture occurred, affecting every Indo-European and Dravidian group in India without exception." Reich pointed out that their work does not show that a substantial migration occurred during this time.[web 13]

Metspalu et al. (2011), representing a collaboration between the Estonian Biocenter and CCMB, confirmed that the Indian populations are characterized by two major ancestry components. One of them is spread at comparable frequency and haplotype diversity in populations of South and West Asia and the Caucasus. The second component is more restricted to South Asia and accounts for more than 50% of the ancestry in Indian populations. Haplotype diversity associated with these South Asian ancestry components is significantly higher than that of the components dominating the West Eurasian ancestry palette.[31]

Segurel et al. (2020)[212] notes the -13910*T Lactase persistence mutation, found in present-day South Asia, first appeared approximately 3,960 BCE, in Ukraine, and spread between 2,000 and 1,500 BCE throughout Eurasia. Earlier Tandon et al. (1981) had studied the distribution of lactase toleration in North and South Indians.[46] Romero et al.(2011)[213] later plotting a decreasing North West to South East Indian cline for the mutations frequency .

Additional components

ArunKumar et al. (2015) discern three major ancestry components, which they call "Southwest Asian", "Southeast Asian" and "Northeast Asian". The Southwest Asian component seems to be a native Indian component, while the Southeast Asian component is related to East Asian populations.[214] Brahmin[needs context] populations "contained 11.4 and 10.6% of Northern Eurasian and Mediterranean components, thereby suggesting a shared ancestry with the Europeans". They note that this fits with earlier studies which "suggested similar shared ancestries with Europeans and Mediterraneans".[214] They further note that

Studies based on uni-parental marker have shown diverse Y-chromosomal haplogroups making up the Indian gene pool. Many of these Y-chromosomal markers show a strong correlation to the linguistic affiliation of the population. The genome-wide variation of the Indian samples in the present study correlated with the linguistic affiliation of the sample.[215]

They conclude that, while there may have been an ancient settlement in the subcontinent, "male-dominated genetic elements shap[ed] the Indian gene pool", and that these elements "have earlier been correlated to various languages", and further note "the fluidity of female gene pools when in a patriarchal and patrilocal society, such as that of India".[216]

Basu et al. (2016) extend the study of Reich et al. (2009) by postulating two other populations in addition to the ANI and ASI: "Ancestral Austro-Asiatic" (AAA) and "Ancestral Tibeto-Burman" (ATB), corresponding to the Austroasiatic and Tibeto-Burman language speakers.[38] According to them, ancestral populations seem to have occupied geographically separated habitats.[39] The ASI and the AAA were early[when?] settlers, who possibly arrived via the southern wave out of Africa.[39] The ANI are related to Central South Asians and entered India through the northwest, while the ATB are related to East Asians and entered India through northeast corridors.[39] They further note that

The asymmetry of admixture, with ANI populations providing genomic inputs to tribal populations (AA, Dravidian tribe, and TB) but not vice versa, is consistent with elite dominance and patriarchy. Males from dominant populations, possibly upper castes, with high ANI component, mated outside of their caste, but their offspring were not allowed to be inducted into the caste. This phenomenon has been previously observed as asymmetry in homogeneity of mtDNA and heterogeneity of Y-chromosomal haplotypes in tribal populations of India as well as the African Americans in United States.[39]

Male-mediated migration

Reich et al. (2009), citing Kivisild et al. (1999), indicate that there has been a low influx of female genetic material since 50,000 years ago, but a "male gene flow from groups with more ANI relatedness into ones with less".[32][note 37]

ArunKumar et al. (2015) "suggest that ancient male-mediated migratory events and settlement in various regional niches led to the present day scenario and peopling of India."[217]

Mahl (2021), in a study of the Brahmin ethnic group, identified the ancient male protagonists of the sampled population could be traced to twelve geographic locations, eleven of which were outside South Asia. Of the Y-DNA haplogroups identified, four were carried by ~83% of those sampled, and of these four, two were of Central Asian origin and one of the Fertile Crescent. All sampled groups were admixed with populations of South Asian origin.[218]

North-south cline

According to Metspalu et al. (2011) there is "a general principal component cline stretching from Europe to south India". This northwest component is shared with populations from the Middle East, Europe and Central Asia, and is thought to represent at least one ancient influx of people from the northwest.[219][clarification needed] According to Saraswathy et al. (2010), there is "a major genetic contribution from Eurasia to North Indian upper castes" and a "greater genetic inflow among North Indian caste populations than is observed among South Indian caste and tribal populations".[web 14] According to Basu et al. (2003) and Saraswathy et al. (2010) certain sample populations of upper caste North Indians show a stronger affinity to Central Asian caucasians, whereas southern Indian Brahmins show a less stronger affinity.[web 14]

Scenarios

While Reich notes that the onset of admixture coincides with the arrival of Indo-European language,[web 2][note 38] according to Metspalu (2011), the commonalities of the ANI with European genes cannot be explained by the influx of Indo-Aryans at ca. 3,500 BP alone.[220] They state that the split of ASI and ANI predates the Indo-Aryan migration,[31] both of these ancestry components being older than 3,500 BP."[221][web 15] Moorjani (2013) states that "We have further shown that groups with unmixed ANI and ASI ancestry were plausibly living in India until this time."[222] Moorjani (2013) describes three scenarios regarding the bringing together of the two groups:[40]

- "migrations that occurred prior to the development of agriculture [8,000–9,000 years before present (BP)]. Evidence for this comes from mitochondrial DNA studies, which have shown that the mitochondrial haplogroups (hg U2, U7, and W) that are most closely shared between Indians and West Eurasians diverged about 30,000–40,000 years BP."

- "Western Asian peoples migrated to India along with the spread of agriculture [...] Any such agriculture related migrations would probably have begun at least 8,000–9,000 years BP (based on the dates for Mehrgarh) and may have continued into the period of the Indus civilization that began around 4,600 years BP and depended upon West Asian crops."

- "migrations from Western or Central Asia from 3,000 to 4,000 years BP, a time during which it is likely that Indo-European languages began to be spoken in the subcontinent. A difficulty with this theory, however, is that by this time India was a densely populated region with widespread agriculture, so the number of migrants of West Eurasian ancestry must have been extraordinarily large to explain the fact that today about half the ancestry in India derives from the ANI."

Pre-agricultural migrations