Orio Palmer

Orio Palmer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 2, 1956 The Bronx, New York City, U.S. |

| Died | September 11, 2001 (aged 45) Manhattan, New York City, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Collapse of the South Tower as part of the 9/11 attacks |

| Resting place | Cemetery of the Holy Rood (Westbury, New York) |

| Education | Associate degree (Electrical Technology) |

| Alma mater | Cardinal Spellman High School; Westchester Community College |

| Television | 9/11 (CBS); In Memoriam: New York City, 9/11/01 (HBO) |

| Spouse | Debbie Palmer[1] |

| Children | 3[1] |

| Awards | Numerous Medals of Valor, Unit Citations |

| Known for | Evacuation efforts during the September 11 attacks |

| Notable work | Numerous papers and articles regarding Firefighting and Firefighter Safety; article(s) regarding Radio communications in High-rise building fires and use of repeaters to ensure communication while fighting High-rise building fires. |

| Firefighter career | |

| Department | New York City Fire Department (1981–2001) Battalion 7 |

Orio Joseph Palmer (March 2, 1956 – September 11, 2001) was a Battalion Chief of the New York City Fire Department who died while rescuing civilians trapped inside the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001.[2][3][1] Palmer led the team of firefighters that reached the 78th floor of the South Tower, the floor where the plane had struck the building.[2][3] As of 2024, his remains have never been identified.

According to The 9/11 Commission Report, audio and video recordings prominently featuring Orio Palmer have played an important role in the ongoing analysis of problems with radio communications during the September 11 attacks.[4]

Early life and education

[edit]Orio Palmer was born in the Bronx, New York City, on March 2, 1956.[5] Palmer graduated from Cardinal Spellman High School in the Bronx, in 1974.[6] He held an associate degree in electrical technology.[7]

He married Debbie Palmer,[1] and they had three children,[1][6] Dana, Keith, and Alyssa.[6][8]

According to John Norman, author of Fire Officer's Handbook of Tactics, Palmer was very fit and ran marathon races.[9] Historian Peter Charles Hoffer wrote that Palmer was "in superb condition".[10]

In 1989, Palmer ran the New York City Marathon for the first time, dedicating his participation in that event to his daughter Dana in honor of her first birthday. He later completed a number of other races and fitness challenges,[11] including a few triathlons.[5]

Career

[edit]Palmer joined the New York City Fire Department, where he eventually became Battalion Chief[5][12] of FDNY's Battalion 7.[5]

Reporter Michael Daly wrote, "The 45-year-old Palmer was one of the department's rising stars, renowned for his smarts and nerve and decency, as well as his physical fitness."[3]

Palmer was the first FDNY member to be awarded the department's physical fitness award five times.[13]

He was said to be one of the "most knowledgeable people in the department" about radio communication in high-rise fires,[6][7] and authored a training article for the department on how to use repeaters to boost radio reception during such emergencies.[7]

September 11 attacks

[edit]North Tower lobby

[edit]Footage of Palmer was used in the CBS film 9/11, and later in the HBO film In Memoriam: New York City, 9/11/01.[14] The video footage was shot by French documentary filmmaker Jules Naudet at the North Tower. It shows Palmer conferring with Deputy Chief Peter Hayden and Assistant Chief Donald Burns at the North Tower. The South Tower had just been hit. The men discuss how to respond to the two towers, and the communications problems they faced. The sound of a falling body hitting pavement outside reverberates. According to Michael Daly, "Palmer stood steady and calm, an air pack on his back, a red flashlight bound with black elastic to his white helmet, a radio in his left hand. His face showed only a readiness to do whatever was needed." The men decided that Burns and Palmer would proceed to the South Tower.[3]

Ascent of South Tower

[edit]

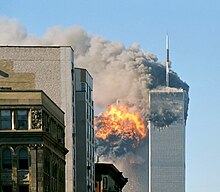

After American Airlines Flight 11 struck the North Tower at 8:46 am, Palmer helped organize operations there. Soon after United Airlines Flight 175 hit the South Tower at 9:03 am, Palmer moved into that building with Chief Burns. Although most elevators had been rendered non-operational,[15] Palmer, who was well versed in elevators, managed to get a freight elevator to bring him and several members of Ladder 15 partway up the building[12] to the 41st floor, halfway to the impact zone, which spanned the 77th to the 85th floors.[15] About 14 or 15 minutes before the South Tower collapsed, a group of people who had survived the plane's impact began their descent from the 78th floor. As they departed, Palmer sent word to Chief Edward Geraghty that a group of 10 people, some of whom exhibited injuries, were heading to an elevator on the 41st floor, the only one left working by the plane's impact. However, on its last trip down, the car became stuck in the shaft. Inside the elevator was a Ladder 15 firefighter who reported that he was trying to break open the walls. It is unclear whether the group of 10 had reached that elevator before it left the 41st floor, but those who listened to the tape said it was most unlikely that they had enough time to escape, by the elevator or by stairs.[16]

When an audiotape of communication with the firefighters was released, it revealed that firefighters did not anticipate the building's collapse. Palmer, issuing an order to one of his subordinates, was recorded seconds before the building collapsed. Peter Charles Hoffer described Palmer's professionalism during the final moments of his life: "Listening to Palmer and his comrades on the recovered tape, one can hear the urgency of men working at high efficiency, but there was never a hint that the clock was running out on them."[10]

Transcripts of Palmer's last broadcast were published in 2002. The actual recordings were made public in 2005, as the result of a lawsuit filed by The New York Times and families of some of the firefighters killed on September 11. Monica Gabrielle of the Skyscraper Safety Campaign commented on the release of the tapes: "Today we are one step closer to learning what happened on 9/11 in NYC — where we excelled, where we failed."[17]

According to The Times of London, "Chief Palmer made it to the impact zone on the 78th floor of the south tower before the building collapsed. Once there the battalion chief reported 'Numerous 10–45s, Code Ones' — fire department code for dead people."[16]

When new tapes were made public in 2006, Palmer's brother-in-law, FDNY Lt. Jim McCaffrey, stated, "It was emotional sitting with my wife and sister-in-law, listening to the tapes. You're hearing him right at that point prior to the collapse, about the things he saw on the 78th floor. Before that, we didn't even know he got higher than the 40th floor."[18]

Role in analysis of 9/11

[edit]

In 2004, The 9/11 Commission Report relied on analysis of the North Tower lobby conversations between Palmer, Peter Hayden and Donald Burns in the film shot by Jules and Gedeon Naudet to better understand what was and was not working on the fire department's communications in those critical minutes. The report stated that, "Of particular concern to the chiefs—in light of FDNY difficulties in responding to the 1993 bombing—was communications capability. One of the chiefs recommended testing the repeater channel to see if it would work." Peter Hayden, who survived, later testified, "People watching on TV certainly had more knowledge of what was happening a hundred floors above us than we did in the lobby.... [W]ithout critical information coming in... it's very difficult to make informed, critical decisions".[4]

The 9/11 Commission carefully analyzed the FDNY radio communications that day, and reported that the battalion chief (Palmer) was able to maintain radio communication that "worked well" with the senior chief in the lobby of the South Tower during the first fifteen minutes of his ascent. A message from a World Trade Center security official (Rick Rescorla) that the impact was on the 78th floor was relayed to Palmer, and he decided to try to take his team to that level. Beginning at 9:21 am, Palmer was no longer able to reach the lobby command post, but his transmissions were recorded and analyzed later. He reached the 78th floor sky lobby, and his team not far behind him were able to free a group of civilians trapped in an elevator at 9:58 am. Palmer radioed that the area was open to the 79th floor, "well into the impact zone", and reported "numerous civilian fatalities in the area". One minute later, at 9:59 am, the South Tower collapsed, killing everyone still inside, including Palmer and FDNY Marshal Ronald Bucca.[4]

Michael Daly concluded that Palmer, "an uncommonly brave fire chief who was one of the department's most knowledgeable minds in communications perished never knowing of warnings [of collapsing floors] telephoned by at least two callers less than 30 stories above him."[3]

Although they lost their lives themselves, Palmer and his crew had played an "indispensable role in ensuring calm in the stairwells, assisting the injured and guiding the evacuees on the lower floors."[19]

Legacy

[edit]

In 2002, a portion of East 234th Street between Vireo and Webster Avenues in the Bronx was renamed "Deputy Chief Orio J. Palmer Way."[20][21]

The New York City Fire Department honored Palmer by renaming its physical fitness award[11] the Deputy Chief Orio Palmer Fitness Award,[22][23] also known as the Orio Palmer Memorial Fitness Award.[24]

At the National 9/11 Memorial, Palmer is memorialized at the South Pool, on Panel S-17.[25]

In an early-morning ceremony on May 10, 2014, the long-unidentified remains of 1,115 victims were transferred from the city medical examiner's to Ground Zero, where they would be placed in a space in the bedrock 70 feet below ground, as part of the 9/11 Museum. Reaction to the move was split among the families of the 9/11 victims, with some hailing the decision, and others protesting the location as inappropriate. Among the latter was Orio Palmer's brother-in-law, FDNY Lt. James McCaffrey, who demanded a ground-level tomb as a more dignified location. McCaffrey said, "The decision to put the human remains of the 9/11 dead in this basement is inherently disrespectful and totally offensive." McCaffrey stated that the remains deserve a place of prominence equal to that of the Memorial's trees and pools, and opined that the ceremony was held early in the morning due to opposition to the decision.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Mai Tran (January 3, 2003). "A Week in West for 9/11 Firefighter Families". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved September 28, 2008.

- ^ a b Flynn, Kevin; Dwyer, Jim (November 9, 2002). "Fire Department Tape Reveals No Awareness of Imminent Doom". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Daly, Michael (August 11, 2002). "His brave voice resounds". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c Kean, Thomas H.; Lee H. Hamilton (2004). The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 298–304, 547–548. ISBN 978-0-393-06041-6.

- ^ a b c d Ratliff, Shannon (September 2022). "The 9/11 Firefighter Whose Name You Need to Know". Rare. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Orio Palmer – Alumni Page". Cardinal Spellman H. S. – Class of 1974. Archived from the original on January 8, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c Dwyer, Jim; Flynn, Kevin (2006). 102 Minutes: The Untold Story of the Fight to Survive Inside the Twin Towers. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-8032-2.

- ^ Palmer, Dana (January 29, 2002). "Orio Joseph Palmer: Letter to a Father". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ Norman, John (2005). Fire Officer's Handbook of Tactics. PennWell Books. p. 341. ISBN 978-1-59370-061-4.

- ^ a b Hoffer, Peter Charles (2006). Seven fires: the urban infernos that reshaped America. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-355-5.

- ^ a b Pachuki, Jenny. "Remembering FDNY Hero Battalion Chief Orio J. Palmer". National 9/11 Memorial & Museum. Archived from the original on April 14, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Daly, Michael (September 11, 2021). "This Son of an FDNY Legend Hunted His Dad's 9/11 Killers Through Five Combat Tours". Daily Beast. Archived from the original on May 8, 2023. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ Higgins, Sean (September 11, 2021). "Park City Remembers the 20th Anniversary of September 11th With Solemn Ceremony". KPCW. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ Bill Egbert; Richard Weir; Bill Hutchinson (May 27, 2002). "9-11 film grips N.Y.ERS HBO documentary all too real for heroes". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ a b "First Chief on the Scene". September 2002.

- ^ a b Dwyer, Jim; Fessenden, Ford (August 4, 2002). "Lost Voices of Firefighters, Some on the 78th Floor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021.

- ^ Bone, James (August 13, 2005). "Voices of courage and terror resurrected by the 9/11 tapes: After four years, families of firefighters have forced release of radio messages". The Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ Dillon, Nancy (March 27, 2006). "CRIES FOR HELP. 9-11 KIN WILL RELIVE TRAGEDY VIA TAPE AS VICTIMS TRAPPED IN TOWERS DELIVER LAST PLEAS". Daily News. New York. Retrieved September 28, 2008. Mirror

- ^ Farmer, John (February 6, 2005). "A September Morning". The Washington Post. Washington, DC. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ^ Gaskell, Stephanie (17 November 2002). "STREET OF HONOR FOR 9/11 HERO". New York Post. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ Orio J. Palmer Way, Historic Districts Council, 3 January 2017, retrieved October 19, 2022

- ^ "S3, E27 Inside the FDNY Fitness Unit with Captain Thomas Tanzosh". FDNY Foundation. Archived from the original on December 1, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Erin (September 10, 2021). "The 9/11 Firefighter Whose Name You Should Know". Medium. Archived from the original on September 11, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ Scoppetta, Nicholas; Cassano, Salvatore J. (December 14, 2006). "Department Order No. 101" (PDF). New York City Fire Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2023. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "South Pool: Panel S-17 - Orio Joseph Palmer". National September 11 Memorial & Museum. Archived from the original on July 27, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ Stepansky, Joseph; Badia, Erik; McShane, Larry (May 11, 2014). "The Anger Remains". Daily News (New York). p. 4.

External links

[edit]- Debunking 911 Conspiracy Theories: The Fires – Orio Palmer, Deputy Chief, Battalion 7

- On Debunking 9/11 Debunking: Examining Dr. David Ray Griffin’s Latest Criticism of the NIST World Trade Center Investigation, by Ryan Mackey (Orio Palmer's observations are discussed on pages 26–27)

- Internet Archive – NY Fire Department's 9/11 Radio Dispatches

- Orio Palmer at Find a Grave

- 1956 births

- 2001 deaths

- Burials at the Cemetery of the Holy Rood

- Cardinal Spellman High School (New York City) alumni

- Emergency workers killed in the September 11 attacks

- Firefighters killed in the line of duty

- Filmed killings

- New York City firefighters

- People murdered in New York City

- Terrorism deaths in New York (state)

- Westchester Community College alumni