Liberty bond

A liberty bond or liberty loan was a war bond that was sold in the United States to support the Allied cause in World War I. Subscribing to the bonds became a symbol of patriotic duty in the United States and introduced the idea of financial securities to many citizens for the first time.

Liberty Bond Issues 1917–1918

[edit]There were four issues of Liberty Bonds:[1]

- April 24, 1917: Emergency Loan Act (Pub. L. 65–3) authorizes issue of $1.9 billion in bonds at 3.5 percent.

- October 1, 1917: Second Liberty Loan offers $3.8 billion in bonds at 4 percent

- April 5, 1918: Third Liberty Loan offers $4.1 billion in bonds at 4.15 percent.

- September 28, 1918: Fourth Liberty Loan offers $6.9 billion in bonds at 4.25 percent.

Interest on up to $30,000 in the bonds was tax exempt only for the First Liberty Bond.[1]

First Liberty Bond Act

[edit]The Emergency Loan Act established a $5 billion aggregate limit on the amount of government bonds issued at 30 years at 3.5% interest, redeemable by the government after 15 years. It raised $2 billion with 5.5 million people purchasing bonds.

Second Liberty Bond Act

[edit]

The 2nd Liberty Loan Act established a $15 billion aggregate limit on the amount of government bonds issued, allowing $3 billion more offered at 25 years at 4% interest, redeemable after 10 years. The amount of the loan totaled $3.8 billion with 9.4 million people purchasing bonds.

Sales difficulties and the subsequent campaign

[edit]The response to the first Liberty Bond was unenthusiastic and although the $2 billion issue reportedly sold out, it probably had to be done below par because the notes traded consistently below par.[2] One reaction to this was to attack bond traders as "unpatriotic" if they sold below par. The Board of Governors of the New York Stock Exchange conducted an investigation of brokerage firms who sold below par to determine if "pro-German influences" were at work. The board forced one such broker to buy the bonds back at par and make a $100,000 donation to the Red Cross.[3] Various explanations were offered for the weakness of the bonds ranging from German sabotage to the rich not buying the bonds because it would give an appearance of tax dodging (the bonds were exempt from some taxes).

A common consensus was that more needed to be done to sell the bonds to small investors and the common man, rather than large concerns. The poor reception of the first issue resulted in a convertible re-issue five months later at the higher interest rate of 4% and with more favorable tax terms. When the new issue arrived it also sold below par, although the Times noted that "no Government bonds can sell at par except temporarily and by accident."[4] The subsequent 4.25% bond priced as low as 94 cents upon arrival.[5]

Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo reacted to the sales problems by creating an aggressive campaign to popularize the bonds.[6] The government used a division of the Committee on Public Information called the Four Minute Men to help sell Liberty Bonds and Thrift Stamps.[7][8][9] Famous artists helped to make posters and movie and stage stars hosted bond rallies. Harry Lauder, Al Jolson, Elsie Janis, Mary Pickford, Theda Bara, Ethel Barrymore, Marie Dressler, Lillian Gish, Fatty Arbuckle, Mabel Normand, Douglas Fairbanks, and Charlie Chaplin were among the celebrities that made public appearances promoting the idea that purchasing a liberty bond was "the patriotic thing to do" during the era.[10] Chaplin also made a short film, The Bond, at his own expense for the drive.[11] The Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts sold the bonds, using the slogan "Every Scout to Save a Soldier".

Beyond these effective efforts, in 1917 the Aviation Section of the U.S. Army Signal Corps established an elite group of Army pilots assigned to the Liberty Bond campaign. The plan for selling bonds was for the pilots to crisscross the country in their Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny" training aircraft in flights of 3 to 5 aircraft. When they arrived over a town, they would perform aerobatic stunts, and put on mock dog fights for the populace.

After performing their air show, they would land on a road, a golf course, or a pasture nearby. By the time they shut down their engines, most of the townspeople, attracted by their performance, would have gathered. At that point, most people had never seen an airplane, nor ridden in one. Routinely each pilot stood in the rear cockpit of his craft and told the assemblage that every person who purchased a Liberty Bond would be taken for a ride in one of the airplanes. The program raised a substantial amount of money. The methodology developed and practiced by the Army was later followed by numerous entrepreneurial flyers known as Barnstormers, who purchased war surplus Jenny airplanes and flew across the country selling airplane rides.

Vast amounts of promotional materials were manufactured. For example, for the third Liberty Loan nine million posters, five million window stickers and 10 million buttons were produced and distributed.[12] The campaign spurred community efforts across the country and resulted in glowing, patriotically-tinged reports on the "success" of the bonds.[13] For the fifth and final loan drive (the Victory Loan) in 1919 the Treasury Department produced steel medallions made from melted down German cannon that had been captured by American troops at Château-Thierry in NW France. The inch-and-a-quarter wide medallions suspended from a red, white, and blue ribbon were awarded by the Department to Victory Liberty Loan campaign volunteers in appreciation of their service in the drive.

Despite all these measures, recent research[14] has shown that patriotic motives played only a minor role in investors' decisions to buy these bonds.

Through the selling of "Liberty bonds," the government raised around $17 billion for the war effort. Considering that there were approximately 100 million Americans at the time, each American, on average, raised $170 on Liberty bonds.

According to the Massachusetts Historical Society, "Because the first World War cost the federal government more than $30 billion (by way of comparison, total federal expenditures in 1913 were only $970 million), these programs became vital as a way to raise funds".[15]

Peak US indebtedness was in August 1919 at a value of $25,596,000,000 for Liberty Bonds, Victory Notes, War Savings Certificates, and other government securities. As early as 1922 the possibility that the war debt could not be paid in full within the expected schedule was raised, and that debt rescheduling may be needed. In 1921 the Treasury Department began issuing short term notes maturing in three to five years to repay the Victory Loan.[16]

Victory Liberty Loan

[edit]A fifth bond issue relating to World War I was released on April 21, 1919. Consisting of $4.5 billion of gold notes at 4.75% interest, they matured after four years but could be redeemed by the government after three. Exempt from all income taxes, they were called at the time "the last of the series of five Liberty Loans."[17] However they were also called the "Victory Liberty Loan," and appear this way on posters of the period.

Repayment

[edit]The first three bonds and the Victory Loan were partially retired during the course of the 1920s, but the majority of these bonds were simply re-financed through other government securities. The Victory Loan, which was to mature in May 1923, was retired with money raised by short term treasury notes which matured after three to five years and issued at 90-day intervals until sufficient funds were raised in 1921. The likelihood of successfully retiring all of the war debt (within the amount of time) was noted as early as 1921.[16] In 1927, the 2nd and 3rd, together worth five billion dollars (25% of all government debt at the time), were called for redemption and refunded through the issuance of other government securities through the Treasury Department. Some of the principal was retired. For example, of the 3.1 billion dollars owed on the 2nd Liberty Bond, 575 million in principal was retired and the rest refinanced. At this same time, the 1st Liberty Bond still had 1.9 billion dollars outstanding in 1927 with a call date for 1932 while the fourth Liberty Bond, with six billion dollars, had a call date for 1932 as well.[18]

Default of the Fourth Liberty Bond

[edit]

The first three Liberty bonds, and the Victory Loan, were retired during the course of the 1920s. However, because the terms of the bonds allowed them to be traded for the later bonds which had superior terms, most of the debt from the first, second, and third Liberty bonds was rolled into the fourth issue.

The fourth Liberty Bond had the following terms:[19]

- Date of Bond: October 24, 1918

- Coupon Rate: 4.25%

- Callable Starting: October 15, 1933

- Maturity Date: October 15, 1938

- Amount Originally Tendered: $6 billion

- Amount Sold: $7 billion

The terms of the bond included: "The principal and interest hereof are payable in United States gold coin of the present standard of value."[20] This type of "gold clause" was common in both public and private contracts of the time, and was intended to guarantee that bond-holders would not be harmed by a devaluation of the currency.

However, when the US Treasury called the fourth bond on April 15, 1934,[20] it defaulted on this term by refusing to redeem the bond in gold, and neither did it account for the devaluation of the dollar from $20.67 per troy ounce of gold (the 1918 standard of value) to $35 per ounce. The 21 million[1] bond holders therefore lost 139 million troy ounces of gold, or approximately 41% of the bond's principal.[citation needed]

The legal basis for the refusal of the US Treasury to redeem in gold was the gold clause resolution (Pub. Res. 73–10), dated June 5, 1933.[21] The Supreme Court later held the gold clause resolution to be unconstitutional under section 4 of the Fourteenth Amendment:[22]

We conclude that the Joint Resolution of June 5, 1933, insofar as it attempted to override the obligation created by the bond in suit, went beyond the congressional power.

However, due to President Franklin D. Roosevelt's elimination of the open gold market with the signing of Executive Order 6102 on April 5, 1933, the Court ruled that the bond-holders' loss was unquantifiable, and that to repay them in dollars according to the 1918 standard of value would be an "unjustified enrichment".[20] The ruling therefore had little practical effect.

Impact

[edit]According to a 2020 study, "counties with higher liberty bond ownership rates turned against the Democratic Party in the presidential elections of 1920 and 1924. This was a reaction to the depreciation of the bonds prior to the 1920 election (when the Democrats held the presidency) and the appreciation of the bonds in the early 1920s (under a Republican president), as the Federal Reserve raised and then subsequently lowered interest rates."[23]

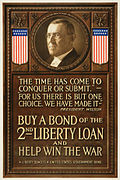

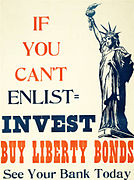

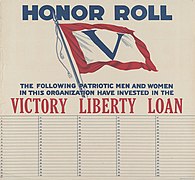

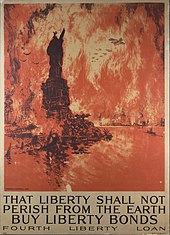

Liberty Bond posters

[edit]- Various posters published to publicize the buying of liberty bonds over time

-

1

-

2

-

3

-

4

-

5

-

6

-

7

-

8

-

9

-

10

-

12

-

13

-

14

-

15

-

16

-

17

-

18

-

19

See also

[edit]- Economic history of the United States#World War I

- Economic history of World War I

- National debt of the United States

- Philadelphia Liberty Loans Parade

- United States home front during World War I

- War bond (World War II)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Sakolski, Aaron Morton. "Wall Street and the Security Markets". 1925

- ^ The Electric Journal, September 1917, p. 51.

- ^ The Financier, June 23, 1917, p. 1741.

- ^ New York Times, November 20, 1917.

- ^ Investment Bankers Association of America Bulletin, Vol. VII, No. 2, October 1, 1918. p. 30.

- ^ Abbott, Charles Cortez (1999). Wall Street and the Security Markets. Harvard Economic Studies, volume 59. Harvard University Press.

- ^ The American Year Book: A Record of Events and Progress, Volume 1918. T. Nelson & Sons. 1919.

- ^ Stone, Oliver; Kuznick, Peter (2014). The Untold History of the United States, Volume 1: Young Readers Edition, 1898-1945. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781481421751.

- ^ The Four Minute Men of Chicago. Chicago, Illinois: United States Committee on Public Information. 1919. p. 25.

- ^ Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History

- ^ Chaplin, Charlie. "My Autobiography." (1964)

- ^ New York Times Magazine, Mar 10, 1918

- ^ New York Times, March 27, 1918, page 4.

- ^ Kang Sung Won, Rockoff Hugh, (2006), "Capitalizing patriotism: the Liberty Loans of WW1", NBER Working Paper No. W11919, 55p.

- ^ Massachusetts Historical Society, Focus on Women and War, June 2002.

- ^ a b Los Angeles Times, October 5, 1922, page IV9.

- ^ Special to The New York Times. (April 14, 1919). "New Loan Fixed at $4,500,000,000; Interest at 4 3/4%" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ Los Angeles Times, January 2, 1928

- ^ Garbade, Kenneth D. "Why the U.S. Treasury Began Auctioning Treasury Bills in 1929." FRBNY Economic Policy Review, July 2008.

- ^ a b c Perry v United States, 294 US 330 (1935)

- ^ Records of the 73rd Congress of the United States, Session I, Chapters 46-48, pp. 112–3.

- ^ Perry v United States, 294 US 330 (1935), Page 294 U. S. 354

- ^ Hilt, Eric; Rahn, Wendy (2020). "Financial Asset Ownership and Political Partisanship: Liberty Bonds and Republican Electoral Success in the 1920s". The Journal of Economic History. 80 (3): 746–781. doi:10.1017/S0022050720000297. ISSN 0022-0507. S2CID 158736064.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chase, Philip M. (2008). William Gibbs McAdoo: The Last Progressive, (1863--1941). p. 130ff. ISBN 9780549982326.

- Childs, C. Frederick. "United States Government Bonds." Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 88 (1920): 43-50. in JSTOR

- Garbade, Kenneth D. (2012). Birth of a Market: The U.S. Treasury Securities Market from the Great War to the Great Depression. MIT Press. pp. 69ff, ch. 5. ISBN 9780262016377.

- Hart Jr, Henry M. "The Gold Clause in United States Bonds" Harvard Law Review 48 (1934): 1057.

- Hollihan, Thomas A. "Propagandizing in the interest of war: A rhetorical study of the committee on public information." Southern Journal of Communication 49.3 (1984): 241-257.

- Kang, Sung Won, and Hugh Rockoff. "Capitalizing Patriotism: The Liberty Loans of World War I" (Paper No. w11919. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2006)

- Kimble, James J. Mobilizing the home front: war bonds and domestic propaganda (Texas A&M University Press, 2006)

Primary sources

[edit]- Browne, Porter Emerson (1918). A Liberty Loan Primer. New York: Liberty Loan Committee, Second Federal Reserve District. OCLC 2315245.

- Lee, Higginson & Co. (1920). Liberty Bonds: A Handbook. London: Higginson & Co. OCLC 318644142.

External links

[edit]- Posters for Liberty Bonds from the Elisabeth Ball Collection of World War I posters

- Liberty Loan documents, and other War Finance documents available on FRASER

- Circulars of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, including circulars on Liberty Loans