Transmission of COVID-19

| Transmission of COVID-19 | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Mode of spread of COVID-19 |

| |

The respiratory route of spread of COVID-19, encompassing larger droplets and aerosols | |

| Specialty | Infection prevention and control |

| Types | Respiratory droplet, airborne transmission, fomites |

| Prevention | Face coverings, quarantine, physical/social distancing, ventilation, disinfection, hand washing, vaccination |

The transmission of COVID-19 is the passing of coronavirus disease 2019 from person to person. COVID-19 is mainly transmitted when people breathe in air contaminated by droplets/aerosols and small airborne particles containing the virus. Infected people exhale those particles as they breathe, talk, cough, sneeze, or sing.[1][2][3][4] Transmission is more likely the closer people are. However, infection can occur over longer distances, particularly indoors.[1][5]

The transmission of the virus is carried out through virus-laden fluid particles, or droplets, which are created in the respiratory tract, and they are expelled by the mouth and the nose. There are three types of transmission: “droplet” and “contact”, which are associated with large droplets, and “airborne”, which is associated with small droplets.[6] If the droplets are above a certain critical size, they settle faster than they evaporate, and therefore they contaminate surfaces surrounding them.[6] Droplets that are below a certain critical size, generally thought to be <100μm diameter, evaporate faster than they settle; due to that fact, they form respiratory aerosol particles that remain airborne for a long period of time over extensive distances.[6][1]

Infectivity can begin four to five days before the onset of symptoms.[7] Infected people can spread the disease even if they are pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic.[8] Most commonly, the peak viral load in upper respiratory tract samples occurs close to the time of symptom onset and declines after the first week after symptoms begin.[8] Current evidence suggests a duration of viral shedding and the period of infectiousness of up to ten days following symptom onset for people with mild to moderate COVID-19, and up to 20 days for persons with severe COVID-19, including immunocompromised people.[9][8]

Infectious particles range in size from aerosols that remain suspended in the air for long periods of time to larger droplets that remain airborne briefly or fall to the ground.[10][11][12][13] Additionally, COVID-19 research has redefined the traditional understanding of how respiratory viruses are transmitted.[13][14] The largest droplets of respiratory fluid do not travel far, but can be inhaled or land on mucous membranes on the eyes, nose, or mouth to infect.[12] Aerosols are highest in concentration when people are in close proximity, which leads to easier viral transmission when people are physically close,[12][13][14] but airborne transmission can occur at longer distances, mainly in locations that are poorly ventilated;[12] in those conditions small particles can remain suspended in the air for minutes to hours.[12][15]

The number of people generally infected by one infected person varies,[16] but it is estimated that the R0 ("R nought" or "R zero") number is around 2.5.[17] The disease often spreads in clusters, where infections can be traced back to an index case or geographical location.[18] Often in these instances, superspreading events occur, where many people are infected by one person.[16]

A person can get COVID-19 indirectly by touching a contaminated surface or object before touching their own mouth, nose, or eyes,[8][19] though strong evidence suggests this does not contribute substantially to new infections.[12] Transmission from human to animal is possible, as in the first case, but the probability of a human contracting the disease from an animal is considered very low.[20] Although it is considered possible, there is no direct evidence of the virus being transmitted by skin to skin contact.[16] Transmission through feces and wastewater have also been identified as possible.[21] The virus is not known to spread through urine, breast milk, food, or drinking water.[19][22] It very rarely transmits from mother to baby during pregnancy.[16]

Infectious period

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

After people are infected with COVID-19, they are able to transmit the disease to other people beginning as early as four to five days before developing symptoms, known as presymptomatic transmission.[8] To reduce such transmission, contact tracing is used to find and alert people who have been in contact with an infected individual in the 48 to 72 hours before they develop symptoms, or before that individual's test date if asymptomatic.[8] Initial reports suggested that this early transmission was restricted to the two-to-three day time window,[23] but an author correction later acknowledged that transmission could begin four to five days before symptom onset.[7]

People are most infectious shortly before and after their symptoms begin[7]—even if mild or non-specific—as the viral load peaks at this time.[8][19]

Based on current evidence, adults with mild to moderate COVID-19 remain infectious (i.e., shed replication-competent SARS-CoV-2) for up to ten days after symptoms begin, although there are few transmission events are observed after five days.[7] Adults with severe to critical COVID-19, or severe immune suppression (immunocompromised persons), may remain infectious (i.e., shed replication-competent SARS-CoV-2) for up to 20 days after symptoms begin.[24][9]

Patients who are tested positive to the virus again after recovery, in case they weren't being reinfected, is found to be not transmitting the virus to others.[25]

Nearly a third of people with COVID-19 remain contagious five days after the onset of symptoms or a positive test. This is reduced to 7% for those who test negative twice with rapid tests on days 5 and 6. Without testing, 5% are contagious on day 10.[26][27]

Asymptomatic transmission

[edit]

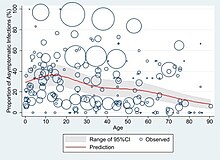

People who are asymptomatic do not show symptoms but still are able to transmit the virus.[12] At least a third of the people who are infected with the virus do not develop noticeable symptoms at any point in time.[28][29][30] Asymptomatic carriers tend not to get tested.[30][31][32]

Persons with asymptomatic COVID-19 infection can have the same viral load as symptomatic and presymptomatic cases, and are able to transmit the virus.[8] However, the infectious period of asymptomatic cases has been observed to be shorter with faster viral clearance.[8]

Dominant mode of transmission: airborne/aerosol

[edit]The dominant mode of transmission of the COVID-19 virus is exposure to respiratory droplets (small liquid particles) carrying infectious virus (i.e., airborne or aerosol transmission).[10][34][35][36][37][2][11][38] Spread occurs when the particles are emitted from the mouth or nose of an infected person when they breathe, cough, sneeze, talk, or sing.[11][39][40] Human breath forms a roughly cone-shaped plume of air; in an infected person, the breath carries out the virus-containing droplets.[40][33] So we expect the highest concentration of virus-containing droplets to be directly in front of an infected person, which suggests that the risk of transmission is greatest within three to six feet of the source of the infection.[10][3] But breath contains many droplets that smaller than 100 micrometres in size, and these can stay suspended in the air for at least minutes and move across a room.[41][42][40][43][44] There is evidence that infectious SARS-CoV-2 survives in aerosols for a few hours.[45] There is substantial evidence for transmission events across a room (i.e., over distances larger than a metre or two) that is associated with being indoors, particularly in poorly ventilated spaces, although even indoor air drafts driven by air conditioning systems may contribute to the spread of respiratory sections.[5][46][47] This has led to statements that transmission occurs most easily in the "three C's": crowded places, close contact settings, and confined and enclosed spaces.[11]

This mode of transmission occurs via an infected person breathing out the virus, which is then carried by the air to a person nearby, or to someone across a room, who then breathes the virus in. Attempts to reduce airborne transmission act on one or more of these steps in transmission.[48] Masks or face coverings are worn to reduce the virus breathed out by an infected person (who may not know they are infected), as well as the virus breathed in by a susceptible person. Social distancing keeps people apart. To prevent virus building up in the air of a room occupied by one or more infected people,[48] ventilation is used to vent virus-laden air to the outside (where it will be diluted in the atmosphere) and replace it with virus-free air from the outside. Alternatively, the air may passed through filters to remove the virus-containing particles. A combination of shielding (protection from large droplet ejection) and air filtering, eliminating aerosols, ("Shield and sink" strategy) is particularly effective in reducing transfer of respiratory materials in indoor settings.[49]

The sneeze resembles a free turbulent jet. The turbulent multiphase cloud contributes critically to increasing the range of the pathogen-bearing drops originating in human coughs and sneezes.[50] The jet's reach is nearly 22 ft in 18.5 seconds and 25 ft in 22 seconds.[51] The shape of the expelled particles is conical, with a spreading angle of 23 degrees.[51][52] The trajectory of the turbulent jet is inclined due to the inclination angle of the nose.[51] Smaller droplets travel a considerable distance as freely suspended tracers and may still get reflected and follow the turbulent cloud.[51] Droplets with a diameter less than 50 μm remain suspended in the cloud for an extended period of time, which allows the cloud to reach heights of 4 to 6 meters, where ventilation systems can be contaminated.[50]

Because physical intimacy and sex involve close contact, in October 2021, New York City Department of Health discouraged unvaccinated persons, immunocompromised people, people over 65, persons with COVID-19, people with a health condition that increases the risk of severe COVID-19, and people who live with someone from one of these groups from engaging in kissing, casual sex, or other activities, and recommended wearing face mask during sex.[53]

The risk of transmission from all size droplets and aerosols is lower in indoor spaces with good ventilation.[54] The risk of outdoor transmission is low.[55][56]

Transmission events occur in workplaces, schools, conferences, sporting venues, dormitories, prisons, shopping facilities, and ships,[57] as well as restaurants,[47] passenger vehicles,[58] religious buildings and choir practices,[59] and hospitals and other healthcare settings.[60] A superspreading event in a Skagit County, Washington, choral practice resulted in 32 to 52 of the 61 attendees infected.[61][5]

An existing model of airborne transmission (the Wells-Riley model) was adapted to help understand why crowded and poorly ventilated spaces promote transmission,[5] with findings supported by aerodynamic analysis of droplet transfer in air-conditioned hospital rooms.[46] Airborne transmission also occurs in healthcare settings; long-distance dispersal of virus particles has been detected in ventilation systems of a hospital.[60]

Some scientists criticized public health authorities, including the WHO, in 2020 for being too slow to recognize airborne (aerosol) transmission of COVID-19 and to update their public health guidance accordingly.[62][63][64][65] By mid-2020, some public health authorities had updated their guidance to reflect the importance of airborne transmission.[10][66] The WHO updated it only by 23 December 2021.[65][11]

Medical procedures designated as aerosol-generating procedures

[edit]There is concern that some medical procedures that affect the mouth and lungs can also generate aerosols, and that this may increase the infection risk. Some medical procedures have been designated as aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs),[11][67] but this been done without measuring the aerosols these procedures produce.[68] The aerosols generated by some AGPs have been measured and found to be less than the aerosols produced by breathing.[69] Less virus (strictly speaking, viral RNA)[a] has been found in the air near intensive care unit (ICUs) with COVID-19 patients than near rooms with COVID-19 patients that are not ICUs.[70] Patients in ICUs are more likely to be subject to mechanically ventilation, an AGP. This suggests that in hospitals, areas near ICUs may actually pose less risk of infection via aerosols. This has led to calls to reconsider AGPs.[68] The WHO recommends the use of filtering facepiece respirators such as N95 or FFP2 masks in settings where aerosol-generating procedures are performed,[19] while the U.S. CDC and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control recommend these controls in all situations related to COVID-19 patient treatment (other than during crisis shortages).[71][72][73]

There is a research that suggests that variation in airway resistance, as measured by CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics), may be a useful tool for predicting the forecast of critically ill COVID-19 patients.[74]

Rarer modes of transmission

[edit]Surface (fomite) transmission

[edit]

A person can get COVID-19 by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it (called a fomite), and then touching their own mouth, nose, or eyes, but it is not the main mode of transmission, and the risk of surface transmission is low.[36][11][16][19][24][34] As of July 2020, "no specific reports which have directly demonstrated fomite transmission" although "People who come into contact with potentially infectious surfaces often also have close contact with the infectious person, making the distinction between respiratory droplet and fomite transmission difficult to discern."[19]

Each contact with a surface contaminated with SARS-CoV-2 has less than a 1 in 10,000 chance of causing an infection.[36] Various surface survival studies have found no detectable viable virus on porous surfaces within minutes to hours, but have found viable virus persisting on non-porous surfaces for days to weeks.[36][19] However, surface-survival studies do not reflect real-world conditions, which are less favorable to the virus.[36] Ventilation and changes in environmental conditions can kill or degrade the virus.[19][36] For example, temperature, humidity, and ultraviolet radiation (sunlight) all influence reductions in viral viability and infectiousness on surfaces.[10] Fomite transmission risk is also reduced because the virus does not transfer efficiently from the surface to the hands, and then from the hands to the mucous membranes (mouth, nose, and eye).[36]

The initial amount of virus on the surface (i.e., the viral load in respiratory droplets) also affects fomite transmission risk.[36] Hand washing and periodic surface cleaning impede indirect contact transmission through fomites.[11][34][36] Fomite transmission can be easily prevented with use of regular household cleaners or disinfection.[36][11][75] When surface survival data and factors affecting real-world transmission are considered, "the risk of fomite transmission after a person with COVID-19 has been in an indoor space is minor after 3 days (72 hours), regardless of when it was last cleaned."[36]

Animal vectors

[edit]Although the COVID-19 virus likely originated in bats, the pandemic is sustained through human-to-human spread, and the risk of animal-to-human spread of COVID-19 is low.[76][77] COVID-19 infections in non-human animals have included companion animals (e.g., domestic cats, dogs, and ferrets); zoo and animal sanctuary residents (e.g., big cats, otters, and non-human primates); mink in mink farms in multiple countries; and wild white-tailed deer in numerous U.S. states.[76] Most animal infections came after the animals were in close contact with a human with COVID-19, such as an owner or caretaker.[76] Experimental research in laboratory settings also shows that other types of mammals (e.g., voles, rabbits, hamsters, pigs, macaques, baboons) can become infected.[76] By contrast, chickens and ducks do not seem to become infected with, or spread, the virus.[76] There is no evidence that the COVID-19 virus can spread to humans from the skin, fur, or hair of pets.[77] The U.S. CDC recommended that pet owners limit their pet's interactions with unvaccinated people outside their household; advises pet owners not to put face coverings on pets, as it could harm them; and states that pets should not be disinfected with cleaning products not approved for animal use.[77] If a pet becomes sick with COVID-19, the CDC recommends that owners "follow similar recommended precautions as for people caring for an infected person at home."[77]

People sick with COVID-19 should avoid contact with pets and other animals, in the same manner that people sick with COVID-19 should avoid contact with people.[77]

Vectors for which there is no evidence of COVID-19 transmission

[edit]Mother to child

[edit]The is no evidence for intrauterine transmission of COVID-19 from pregnant women to their fetuses.[19] Studies have not found any viable virus in breast milk.[19] Breast milk is unlikely to spread the COVID-19 virus to babies.[78][79] Noting the benefits of breastfeeding, the WHO recommends that mothers with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be encouraged to initiate or continue to breastfeed, while taking proper infection prevention and control measures.[79][19]

Food and water

[edit]No evidence suggests that handling food or consuming food is associated with transmission of COVID-19.[80][81] The COVID-19 virus had poor survivability on surfaces;[80] less than 1 in 10,000 contacts with contaminated surfaces, including non-food-related surfaces, lead to infection.[36] As a result, the risk of spread from food products or packaging is very low.[81] Public health authorities recommend that people follow practice good hygiene by washing hands with soap and water before preparing and consuming food.[80][81]

The COVID-19 virus has not been detected in drinking water.[82] Conventional water treatment (filtration and disinfection) inactivates or removes the virus.[82] COVID-19 virus RNA is found in untreated wastewater,[82][22][83][a] but there is no evidence of COVID-19 transmission through exposure to untreated wastewater or sewerage systems.[82] There is also no evidence that COVID-19 transmission to humans occurs through water in swimming pools, hot tubs, or spas.[82]

Other

[edit]While SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in the urine and feces of some persons infected with COVID-19,[a] there is no evidence of COVID-19 transmission through feces or urine.[19][82] COVID-19 is not an insect-borne disease; there is also no evidence that mosquito are a vector for COVID-19.[84] COVID-19 is not a sexually transmitted infection; while the virus has been found in the semen of people who have COVID-19, there is no evidence that the virus spreads through semen or vaginal fluid,[53] however transmission during sexual activities is still possible due to proximity during intimate activities which enable transmission through other paths.[85]

Transmission rate, patterns, clusters

[edit]Observations from early variants

[edit]Many people do not transmit the virus, but some transmit to many people, and the virus is considered to be "over dispersed" – the transmission rate has high heterogeneity.[16][86] "Super-spreading events" occur from this minority of infected people, generally indoors and usually in high-risk venues where people remain in close proximity and poor ventilation for an extended period, such as restaurants, nightclubs, and places of worship.[16][87] Such crowded conditions enable the virus to spread easily via aerosols,[11] they can create clusters of cases, where infections can be traced back to an index case or geographical location.[18] Another important site for transmission is between members of the same household,[16] as well as hospitals due to the abundance of pathogens present.[88] Traffic vehicles are also a site for transmission, since the control of the pathogen there is harder due to the weak ventilation system and the high density of people.[88] Emergency departments are also great sites for transmission of COVID-19.[89] The dispersion of respiratory droplets can be influenced by various factors, including the ventilation system, the number of infected patients, and their movements, which highlights the importance of proper ventilation and air filtration systems in reducing the spread of COVID-19 within an emergency department setting.[89]

COVID-19 is more infectious than influenza, but less so than measles.[34] Estimates of the number of people infected by one person with COVID-19—the basic reproduction number (R0)—have varied. In November 2020, a systematic review estimated R0 of the original Wuhan strain to be approximately 2.87 (95% CI, 2.39–3.44).[90] The R0 of the Delta variant, which became the dominant variant of COVID-19 in 2021, is substantially higher. Among five studies catalogued in October 2021, Delta's mean estimate R0 was 5.08.[91]

Temperature is also a factor that affects the transmissibility of the virus. At elevated temperatures and low virus concentration rates the virus is in its weak state[92] and the spreading of it is strenuously. At low temperatures and excessive virus concentration rates the virus is in its robust state[92] and the spreading of it is unchallenged.

Observations from Omicron and later

[edit]In January 2022, William Schaffner, professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, compared the contagiousness of the Omicron variant to that of the measles.[93]

On 15 December 2021, Jenny Harries, head of the UK Health Security Agency, told a parliamentary committee that the doubling time of COVID-19 in most regions of the UK was now less than two days despite the country's high vaccination rate. She said that the Omicron variant of COVID-19 is "probably the most significant threat since the start of the pandemic", and that the number of cases in the next few days would be "quite staggering compared to the rate of growth that we've seen in cases for previous variants".[94]Effect of face masks and face shields

[edit]Source control is the principal mode of protection of COVID-19[95] after receiving the vaccine. There are many types of face masks, including surgical mask, two-layered face mask, face shield, and N95 respirator. A surgical mask is the least effective means of preventing particle leakage since the leaked particles due to a sneeze travelling a distance of 2.5 ft.[51] The combination of a surgical mask with a face shield restricts the forward motion of particles notably.[51] A two-layered face mask has noticeable leakage in the forward direction, but with the addition of a cotton stitch there is significantly less leakage of particles.[51] The combination of a two-layered face mask and a face shield effectively restricts the leakage in the forward direction.[51] The face shield enables particles to escape from below it, and thus it is not recommended for protecting the spreading of the virus.[51] An N95 respirator completely restricts the forward leakage of particles, but in a badly fitting respirator, a significant amount of particles escape through the gap between the nose and the mask.[96][51]

None of the protective face masks and face shields completely block the escape of particles projected by a sneeze, but they all effectively reduce the leakage and reach of the sneeze within 1–3 ft. The N95 respirator is the best face coverage for mitigating the spread because it completely impedes the forward leakage of the particles.[51] The widely accepted safe distance of 6 ft is highly underestimated for sneezing.[51] Researchers strongly recommend using the elbow or hands to prevent droplet leakage even when wearing face masks during sneezing and coughing.[51] Wearing masks in indoor spaces reduces the risk of transmission,[97] but it is recommended to immediately evacuate any space where sneezing has occurred.[51]

Effect of vaccination

[edit]Early variants

[edit]The Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, AstraZeneca and Janssen COVID-19 vaccines provide effective protection against COVID-19, including against severe disease, hospitalisation, and death, and "a growing body of evidence suggests that COVID-19 vaccines also reduce asymptomatic infection and transmission" as chains of transmission are interrupted by vaccines.[98] While fully vaccinated people can still become infected and potentially transmit the virus to others (particularly in areas of widespread community transmission), they do so at a much lower rate than unvaccinated people.[98] The primary cause of continued spread of COVID-19 is transmission between unvaccinated people.[98]

Omicron and later

[edit]Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) and Moderna (mRNA-1273) mRNA vaccines provide reduced protection against asymptomatic disease but do reduce the risk of serious illness.[99][100][101] On 22 December 2021, the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team reported an about 41% (95% CI, 37–45%) lower risk of a hospitalization requiring a stay of at least 1 night compared to the Delta variant, and that the data suggested that recipients of 2 doses of the Pfizer–BioNTech, the Moderna or the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine were substantially protected from hospitalization.[102] In January 2022, results from Israel suggested that a fourth dose is only partially effective against Omicron. Many cases of infection broke through, albeit "a bit less than in the control group", even though trial participants had higher antibody levels after the fourth dose.[103] On 23 December 2021, Nature indicates that, though Omicron likely weakens vaccine protection, reasonable effectiveness against Omicron may be maintained with currently available vaccination and boosting approaches.[104][105]

In December, studies, some of which using large nationwide datasets from either Israel and Denmark, found that vaccine effectiveness of multiple common two-dosed COVID-19 vaccines is substantially lower against the Omicron variant than for other common variants including the Delta variant, and that a new (often a third) dose – a booster dose – is needed and effective, as it substantially reduces deaths from the disease compared to cohorts who received no booster but two doses.[106][107][108][109][110][111]

Vaccines continue to be recommended for Omicron and its subvariants. Professor Paul Morgan, immunologist at Cardiff University said, "I think a blunting rather than a complete loss [of immunity] is the most likely outcome. The virus can't possibly lose every single epitope on its surface, because if it did that spike protein couldn't work any more. So, while some of the antibodies and T cell clones made against earlier versions of the virus, or against the vaccines may not be effective, there will be others, which will remain effective. (...) If half, or two-thirds, or whatever it is, of the immune response is not going to be effective, and you're left with the residual half, then the more boosted that is the better."[112] Professor Francois Balloux of the Genetics Institute at University College London said, "From what we have learned so far, we can be fairly confident that – compared with other variants – Omicron tends to be better able to reinfect people who have been previously infected and received some protection against COVID-19. That is pretty clear and was anticipated from the mutational changes we have pinpointed in its protein structure. These make it more difficult for antibodies to neutralise the virus."[113]

BA.1 and BA.2

[edit]A January 2022 study by the UK Health Security Agency found that vaccines afforded similar levels of protection against symptomatic disease by BA.1 and BA.2, and in both it was considerably higher after two doses and a booster than two doses without booster,[114][115] though because of the gradually waning effect of vaccines, further booster vaccination may later be necessary.[116]

BA.4 and BA.5

[edit]In May 2022, a preprint indicated Omicron subvariants BA.4 and BA.5 could cause a large share of COVID-19 reinfections, beyond the increase of reinfections caused by the Omicron lineage, even for people who were infected by Omicron BA.1 due to increases in immune evasion, especially for the unvaccinated. However, the observed escape of BA.4 and BA.5 from immunity by a BA.1 infection is more moderate than of BA.1 against studied prior cases of immunity (such as immunity from specific vaccines).[117][118]

Immunity from an Omicron infection for unvaccinated and previously uninfected was found to be weak "against non-Omicron variants",[119] albeit at the time Omicron is, by a large margin, the dominant variant in sequenced human cases.[120]

BQ.1 and BQ.1.1

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Viral RNA is much easier to detect and quantify than counting the live virus. The results make for weaker evidence, however, as inactive viruses still contain detectable levels of RNA. For airborne studies where the transmission is otherwise confirmed, RNA would be an acceptable surrogate for viral load; for paths that are not confirmed, however, RNA is not as convincing.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Wang CC, Prather KA, Sznitman J, Jimenez JL, Lakdawala SS, Tufekci Z, et al. (August 2021). "Airborne transmission of respiratory viruses". Science. 373 (6558). doi:10.1126/science.abd9149. PMC 8721651. PMID 34446582.

- ^ a b Greenhalgh T, Jimenez JL, Prather KA, Tufekci Z, Fisman D, Schooley R (May 2021). "Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2". Lancet. 397 (10285): 1603–1605. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00869-2. PMC 8049599. PMID 33865497.

- ^ a b Bourouiba L (13 July 2021). "Fluid Dynamics of Respiratory Infectious Diseases". Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 23 (1): 547–577. doi:10.1146/annurev-bioeng-111820-025044. hdl:1721.1/131115. PMID 34255991. S2CID 235823756. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Stadnytskyi V, Bax CE, Bax A, Anfinrud P (2 June 2020). "The airborne lifetime of small speech droplets and their potential importance in SARS-CoV-2 transmission". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (22): 11875–11877. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11711875S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2006874117. PMC 7275719. PMID 32404416.

- ^ a b c d Miller SL, Nazaroff WW, Jimenez JL, Boerstra A, Buonanno G, Dancer SJ, et al. (March 2021). "Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by inhalation of respiratory aerosol in the Skagit Valley Chorale superspreading event". Indoor Air. 31 (2): 314–323. Bibcode:2021InAir..31..314M. doi:10.1111/ina.12751. PMC 7537089. PMID 32979298.

- ^ a b c Mittal R (2020). "The flow physics of COVID-19". Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 894. arXiv:2004.09354. Bibcode:2020JFM...894F...2M. doi:10.1017/jfm.2020.330. S2CID 215827809.

- ^ a b c d He X, Lau EH, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. (September 2020). "Author Correction: Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19". Nature Medicine. 26 (9): 1491–1493. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1016-z. PMC 7413015. PMID 32770170. S2CID 221050261.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Communicable Diseases Network Australia. "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): CDNA National Guidelines for Public Health Units". 5.1. Communicable Diseases Network Australia/Australian Government Department of Health.

- ^ a b "Clinical Questions about COVID-19: Questions and Answers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 4 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Scientific Brief: SARS-CoV-2 Transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): How is it transmitted?". World Health Organization. 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g • "COVID-19: epidemiology, virology and clinical features". GOV.UK. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

• Communicable Diseases Network Australia. "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) - CDNA Guidelines for Public Health Units". Version 4.4. Australian Government Department of Health. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

• Public Health Agency of Canada (3 November 2020). "COVID-19: Main modes of transmission". aem. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

• "Transmission of COVID-19". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 26 January 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

• Meyerowitz EA, Richterman A, Gandhi RT, Sax PE (January 2021). "Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: A Review of Viral, Host, and Environmental Factors". Annals of Internal Medicine. 174 (1): 69–79. doi:10.7326/M20-5008. ISSN 0003-4819. PMC 7505025. PMID 32941052. - ^ a b c Tang JW, Marr LC, Li Y, Dancer SJ (April 2021). "Covid-19 has redefined airborne transmission". BMJ. 373: n913. doi:10.1136/bmj.n913. PMID 33853842.

- ^ a b Morawska L, Allen J, Bahnfleth W, Bluyssen PM, Boerstra A, Buonanno G, et al. (May 2021). "A paradigm shift to combat indoor respiratory infection" (PDF). Science. 372 (6543): 689–691. Bibcode:2021Sci...372..689M. doi:10.1126/science.abg2025. PMID 33986171. S2CID 234487289. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Biswas Riddhideep, Pal Anish, Pal Ritam, Sarkar Sourav, Mukhopadhyay Achintya (2022). "Risk assessment of COVID infection by respiratory droplets from cough for various ventilation scenarios inside an elevator: An OpenFOAM-based computational fluid dynamics analysis". Physics of Fluids. 34 (1): 013318. arXiv:2109.12841. Bibcode:2022PhFl...34a3318B. doi:10.1063/5.0073694. PMC 8939552. PMID 35340680. S2CID 245828044.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Meyerowitz EA, Richterman A, Gandhi RT, Sax PE (January 2021). "Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: A Review of Viral, Host, and Environmental Factors". Annals of Internal Medicine. 174 (1): 69–79. doi:10.7326/M20-5008. ISSN 0003-4819. PMC 7505025. PMID 32941052.

- ^ CDC (11 February 2020). "Healthcare Workers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ a b Liu T, Gong D, Xiao J, Hu J, He G, Rong Z, et al. (October 2020). "Cluster infections play important roles in the rapid evolution of COVID-19 transmission: A systematic review". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 99: 374–380. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.073. PMC 7405860. PMID 32768702.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions" (PDF). World Health Organization. 9 July 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 and Your Health". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020.

- ^ "Transmission risk of COVID-19 from sewage spills into rivers can now be quickly quantified". ScienceDaily.

- ^ a b "Water, sanitation, hygiene, and waste management for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19" (PDF). www.who.int. 29 July 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ He X, Lau EH, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. (1 May 2020). "Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19". Nature Medicine. 26 (5): 672–675. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. PMID 32296168. S2CID 215761082.

- ^ a b "Q & A on COVID-19: Basic facts". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 21 September 2021.

- ^ Rasmussen A (4 September 2020). "What We Really Know About the Risk of Coronavirus Reinfection – The Wire Science".

- ^ "One in seven could still be infectious after five-day Covid isolation". The Guardian. 12 January 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "Here's how long people with COVID-19 might remain contagious, according to the best available data". Business Insider. 22 January 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ a b Wang B, Andraweera P, Elliott S, Mohammed H, Lassi Z, Twigger A, et al. (March 2023). "Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Age: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 42 (3): 232–239. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000003791. PMC 9935239. PMID 36730054.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Oran DP, Topol EJ (May 2021). "The Proportion of SARS-CoV-2 Infections That Are Asymptomatic : A Systematic Review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 174 (5): 655–662. doi:10.7326/M20-6976. PMC 7839426. PMID 33481642.

- "Transmission of COVID-19". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Nogrady B (November 2020). "What the data say about asymptomatic COVID infections". Nature. 587 (7835): 534–535. Bibcode:2020Natur.587..534N. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03141-3. PMID 33214725.

- ^ a b Gao Z, Xu Y, Sun C, Wang X, Guo Y, Qiu S, et al. (February 2021). "A systematic review of asymptomatic infections with COVID-19". Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection = Wei Mian Yu Gan Ran Za Zhi. 54 (1): 12–16. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.001. PMC 7227597. PMID 32425996.

- ^ Oran DP, Topol EJ (September 2020). "Prevalence of Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection : A Narrative Review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 173 (5): 362–367. doi:10.7326/M20-3012. PMC 7281624. PMID 32491919.

- ^ Lai CC, Liu YH, Wang CY, Wang YH, Hsueh SC, Yen MY, et al. (June 2020). "Asymptomatic carrier state, acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Facts and myths". Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection = Wei Mian Yu Gan Ran Za Zhi. 53 (3): 404–412. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2020.02.012. PMC 7128959. PMID 32173241.

- ^ a b Abkarian M, Mendez S, Xue N, Yang F, Stone HA (October 2020). "Speech can produce jet-like transport relevant to asymptomatic spreading of virus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (41): 25237–25245. arXiv:2006.10671. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11725237A. doi:10.1073/pnas.2012156117. PMC 7568291. PMID 32978297.

- ^ a b c d "How COVID-19 Spreads". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 14 July 2021.

- ^ "COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 13 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Surface (Fomite) Transmission for Indoor Community Environments". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 April 2021.

- ^ Samet JM, Prather K, Benjamin G, Lakdawala S, Lowe JM, Reingold A, et al. (January 2021). "Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: What We Know". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 73 (10): 1924–1926. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab039. PMC 7929061. PMID 33458756.

- ^ Santarpia JL, Herrera VL, Rivera DN, Ratnesar-Shumate S, Reid SP, Ackerman DN, et al. (August 2021). "The size and culturability of patient-generated SARS-CoV-2 aerosol". Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. 32 (5): 706–711. doi:10.1038/s41370-021-00376-8. PMC 8372686. PMID 34408261.

- ^ a b c Bourouiba L (5 January 2021). "The Fluid Dynamics of Disease Transmission". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 53 (1): 473–508. Bibcode:2021AnRFM..53..473B. doi:10.1146/annurev-fluid-060220-113712. ISSN 0066-4189. S2CID 225114407.

- ^ de Oliveira PM, Mesquita LC, Gkantonas S, Giusti A, Mastorakos E (January 2021). "Evolution of spray and aerosol from respiratory releases: theoretical estimates for insight on viral transmission". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 477 (2245): 20200584. Bibcode:2021RSPSA.47700584D. doi:10.1098/rspa.2020.0584. PMC 7897643. PMID 33633490.

- ^ Lednicky JA, Lauzardo M, Fan ZH, Jutla A, Tilly TB, Gangwar M, et al. (November 2020). "Viable SARS-CoV-2 in the air of a hospital room with COVID-19 patients". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 100: 476–482. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.025. PMC 7493737. PMID 32949774.

- ^ Balachandar S, Zaleski S, Soldati A, Ahmadi G, Bourouiba L (2020). "Host-to-host airborne transmission as a multiphase flow problem for science-based social distance guidelines". International Journal of Multiphase Flow. 132: 103439. arXiv:2008.06113. Bibcode:2020IJMF..13203439B. doi:10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2020.103439. PMC 7471834.

- ^ Netz RR (August 2020). "Mechanisms of Airborne Infection via Evaporating and Sedimenting Droplets Produced by Speaking". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 124 (33): 7093–7101. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c05229. PMC 7409921. PMID 32668904.

- ^ van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. (April 2020). "Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (16): 1564–1567. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2004973. PMC 7121658. PMID 32182409.

- ^ a b Hunziker P (1 October 2021). "Minimising exposure to respiratory droplets, 'jet riders' and aerosols in air-conditioned hospital rooms by a 'Shield-and-Sink' strategy". BMJ Open. 11 (10): e047772. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047772. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 8520596. PMID 34642190.

- ^ a b Li Y, Qian H, Hang J, Chen X, Cheng P, Ling H, et al. (June 2021). "Probable airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a poorly ventilated restaurant". Building and Environment. 196: 107788. Bibcode:2021BuEnv.19607788L. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107788. PMC 7954773. PMID 33746341.

- ^ a b Prather KA, Wang CC, Schooley RT (June 2020). "Reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2". Science. 368 (6498): 1422–1424. Bibcode:2020Sci...368.1422P. doi:10.1126/science.abc6197. PMID 32461212.

- ^ Hunziker P (1 October 2021). "Minimising exposure to respiratory droplets, 'jet riders' and aerosols in air-conditioned hospital rooms by a 'Shield-and-Sink' strategy". BMJ Open. 11 (10): e047772. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047772. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 8520596. PMID 34642190.

- ^ a b Bourouiba L, Dehandschoewercker E, Bush JW (24 March 2014). "Violent expiratory events: on coughing and sneezing". Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 745: 537–563. Bibcode:2014JFM...745..537B. doi:10.1017/jfm.2014.88. hdl:1721.1/101386. ISSN 0022-1120. S2CID 2102358.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Arumuru V, Pasa J, Samantaray SS (1 November 2020). "Experimental visualization of sneezing and efficacy of face masks and shields". Physics of Fluids. 32 (11): 115129. Bibcode:2020PhFl...32k5129A. doi:10.1063/5.0030101. ISSN 1070-6631. PMC 7684680. PMID 33244217.

- ^ Bahl P, de Silva C, MacIntyre CR, Bhattacharjee S, Chughtai AA, Doolan C (2 November 2021). "Flow dynamics of droplets expelled during sneezing". Physics of Fluids. 33 (11): 111901. Bibcode:2021PhFl...33k1901B. doi:10.1063/5.0067609. ISSN 1070-6631. PMC 8597717. PMID 34803362.

- ^ a b "Safer Sex and COVID-19" (PDF). New York City Department of Health. 18 June 2021.

- ^ The Lancet Respiratory Medicine (December 2020). "COVID-19 transmission-up in the air". Editorial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 8 (12): 1159. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30514-2. PMC 7598535. PMID 33129420.

- ^ Tommaso Celeste Bulfone, Mohsen Malekinejad, George W. Rutherford, Nooshin Razani (15 February 2021). "Outdoor Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Viruses: A Systematic Review". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 223 (4): 550–561. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa742. PMC 7798940. PMID 33249484.

- ^ "Participate in Outdoor and Indoor Activities". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 19 August 2021.

- ^ Leclerc QJ, Fuller NM, Knight LE, Funk S, Knight GM (5 June 2020). "What settings have been linked to SARS-CoV-2 transmission clusters?". Wellcome Open Research. 5: 83. doi:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15889.2. PMC 7327724. PMID 32656368.

- ^ Varghese Mathai, Asimanshu Das, Jeffrey A. Bailey, Kenneth Breuer (1 January 2021). "Airflows inside passenger cars and implications for airborne disease transmission". Science Advances. 7 (1). arXiv:2007.03612. Bibcode:2021SciA....7..166M. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe0166. PMC 7775778. PMID 33277325.

- ^ Katelaris AL, Wells J, Clark P, Norton S, Rockett R, Arnott A, et al. (June 2021). "Epidemiologic Evidence for Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during Church Singing, Australia, 2020". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 27 (6): 1677–1680. doi:10.3201/eid2706.210465. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 8153858. PMID 33818372.

- ^ a b Nissen K, Krambrich J, Akaberi D, Hoffman T, Ling J, Lundkvist Å, et al. (November 2020). "Long-distance airborne dispersal of SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 wards". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 19589. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1019589N. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-76442-2. PMC 7659316. PMID 33177563.

- ^ Hamner L, Dubbel P, Capron I, Ross A, Jordan A, Lee J, et al. (May 2020). "High SARS-CoV-2 Attack Rate Following Exposure at a Choir Practice - Skagit County, Washington, March 2020". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (19): 606–610. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e6. PMID 32407303.

- ^ Lewis D (July 2020). "Mounting evidence suggests coronavirus is airborne - but health advice has not caught up". Nature. 583 (7817): 510–513. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..510L. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02058-1. PMID 32647382. S2CID 220470431.

- ^ Zhang R, Li Y, Zhang AL, Wang Y, Molina MJ (June 2020). "Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (26): 14857–14863. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11714857Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.2009637117. PMC 7334447. PMID 32527856.

- ^ Tanne JH (September 2020). "Covid-19: CDC publishes then withdraws information on aerosol transmission". BMJ. 370: m3739. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3739. PMID 32973037. S2CID 221881893.

- ^ a b Lewis D (6 April 2022). "Why the WHO took two years to say COVID is airborne". Nature. 604 (7904): 26–31. Bibcode:2022Natur.604...26L. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-00925-7. PMID 35388203. S2CID 248000902.

- ^ "COVID-19: Main modes of transmission". Public Health Agency of Canada. 3 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J (2012). "Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e35797. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735797T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. PMC 3338532. PMID 22563403.

- ^ a b Hamilton F, Arnold D, Bzdek BR, Dodd J, Reid J, Maskell N (July 2021). "Aerosol generating procedures: are they of relevance for transmission of SARS-CoV-2?". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 9 (7): 687–689. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00216-2. PMC 8102043. PMID 33965002.

- ^ Wilson NM, Marks GB, Eckhardt A, Clarke AM, Young FP, Garden FL, et al. (November 2021). "The effect of respiratory activity, non-invasive respiratory support and facemasks on aerosol generation and its relevance to COVID-19". Anaesthesia. 76 (11): 1465–1474. doi:10.1111/anae.15475. PMC 8250912. PMID 33784793.

- ^ Grimalt JO, Vílchez H, Fraile-Ribot PA, Marco E, Campins A, Orfila J, et al. (September 2021). "Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in hospital areas". Environmental Research. 204 (Pt B): 112074. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112074. ISSN 0013-9351. PMC 8450143. PMID 34547251.

- ^ "Infection prevention and control and preparedness for COVID-19 in healthcare settings - fifth update" (PDF).

- ^ "Respiratory Protection During Outbreaks: Respirators versus Surgical Masks | | Blogs | CDC". 9 April 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ CDC (11 February 2020). "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Pan Sy, Ding M, Huang J, Cai Y, Huang Yz (September 2021). "Airway resistance variation correlates with prognosis of critically ill COVID-19 patients: A computational fluid dynamics study". Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 208: 106257. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106257. ISSN 0169-2607. PMC 8231702. PMID 34245951.

- ^ "COVID-19: Cleaning And Disinfecting Your Home". www.cdc.gov. 27 May 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "COVID-19 and Animals". www.cdc.gov. 6 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "COVID-19: If You Have Pets". www.cdc.gov. 29 June 2021.

- ^ "Breastfeeding and Caring for Newborns if You Have COVID-19". 18 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Breastfeeding and COVID-19". www.who.int. World Health Organization. 23 June 2020. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c "Questions and answers on COVID-19: Various". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 8 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "Food Safety and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Water and COVID-19 FAQs: Information about Drinking Water, Treated Recreational Water, and Wastewater". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 23 April 2020.

- ^ Corpuz MV, Buonerba A, Vigliotta G, Zarra T, Ballesteros F, Campiglia P, et al. (November 2020). "Viruses in wastewater: occurrence, abundance and detection methods". The Science of the Total Environment. 745: 140910. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.74540910C. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140910. PMC 7368910. PMID 32758747.

- ^ Yan-Jang S. Huang, Dana L. Vanlandingham, Ashley N. Bilyeu, Haelea M. Sharp, Susan M. Hettenbach, Stephen Higgs (17 July 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 failure to infect or replicate in mosquitoes: an extreme challenge". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 11915. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1011915H. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-68882-7. PMC 7368071. PMID 32681089.

- ^ "Sex and Coronavirus". www.umms.org.

- ^ Endo A, Abbott S, Kucharski AJ, Funk S (2020). "Estimating the overdispersion in COVID-19 transmission using outbreak sizes outside China". Wellcome Open Research. 5: 67. doi:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15842.3. PMC 7338915. PMID 32685698.

- ^ Kohanski MA, Lo LJ, Waring MS (October 2020). "Review of indoor aerosol generation, transport, and control in the context of COVID-19". International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology. 10 (10): 1173–1179. doi:10.1002/alr.22661. PMC 7405119. PMID 32652898.

- ^ a b Peng S, Chen Q, Liu E (April 2021). "Corrigendum to "The role of computational fluid dynamics tools on investigation of pathogen transmission: Prevention and control" [Sci. Total Environ. 746 (2020) 142090]". Science of the Total Environment. 764: 142862. Bibcode:2021ScTEn.76442862P. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142862. ISSN 0048-9697. PMC 8445364. PMID 33138993.

- ^ a b Fawwaz Alrebi O, Obeidat B, Atef Abdallah I, Darwish EF, Amhamed A (May 2022). "Airflow dynamics in an emergency department: A CFD simulation study to analyse COVID-19 dispersion". Alexandria Engineering Journal. 61 (5): 3435–3445. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2021.08.062. ISSN 1110-0168. S2CID 237319234.

- ^ Billah MA, Miah MM, Khan MN (11 November 2020). "Reproductive number of coronavirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on global level evidence". PLOS ONE. 15 (11). e0242128. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1542128B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0242128. PMC 7657547. PMID 33175914.

- ^ Ying Liu, Joacim Rocklöv (October 2021). "The reproductive number of the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 is far higher compared to the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 virus". Journal of Travel Medicine. 28 (7). doi:10.1093/jtm/taab124. PMC 8436367. PMID 34369565.

- ^ a b Dbouk T, Drikakis D (1 February 2021). "Fluid dynamics and epidemiology: Seasonality and transmission dynamics". Physics of Fluids. 33 (2): 021901. Bibcode:2021PhFl...33b1901D. doi:10.1063/5.0037640. ISSN 1070-6631. PMC 7976049. PMID 33746486.

- ^ Rozsa M, Karlis N (28 January 2022). "Omicron variant of COVID-19 may be the most contagious virus to ever exist". Salon. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ "LIVE – Covid: 'Staggering' Omicron case numbers expected – top health official". BBC News. 15 December 2021. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021. See entry for 10:05

- ^ Hazard JM, Cappa CD (June 2022). "Performance of Valved Respirators to Reduce Emission of Respiratory Particles Generated by Speaking". Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 9 (6): 557–560. Bibcode:2022EnSTL...9..557H. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.2c00210. PMID 37552726.

- ^ Yu Y, Jiang L, Zhuang Z, Liu Y, Wang X, Liu J, et al. (2014). "Fitting Characteristics of N95 Filtering-Facepiece Respirators Used Widely in China". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e85299. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...985299Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085299. PMC 3897424. PMID 24465528.

- ^ Ho CK (2021). "Modelling Airborne Transmission and Ventilation Impacts of a COVID-19 Outbreak in a Restaurant in Guangzhou, China". International Journal of Computational Fluid Dynamics. 35 (9): 708–726. Bibcode:2021IJCFD..35..708H. doi:10.1080/10618562.2021.1910678. OSTI 1778059. S2CID 233596966.

- ^ a b c "Science Brief: COVID-19 Vaccines and Vaccination". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 September 2021.

- ^ Zhou H, Møhlenberg M, Thakor JC, Tuli HS, Wang P, Assaraf YG, et al. (21 September 2022). "Sensitivity to Vaccines, Therapeutic Antibodies, and Viral Entry Inhibitors and Advances To Counter the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 35 (3): e00014–22. doi:10.1128/cmr.00014-22. PMC 9491202. PMID 35862736.

- ^ "Pfizer And BioNTech Provide Update On Omicron Variant" (Press release). New York City and Mainz: Pfizer. 8 December 2021. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation in England, technical briefing 31 (PDF) (Briefing). Public Health England. 10 December 2021. pp. 3–5, 20–22. GOV-10645. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ Ferguson N, Ghani A, Hinsley W, Volz E (22 December 2021). Hospitalisation risk for Omicron cases in England (Technical report). WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Modelling, MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis. Imperial College London. doi:10.25561/93035. Report 50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2021.

- ^ "Israeli trial, world's first, finds 4th dose 'not good enough' against Omicron". www.timesofisrael.com. 18 January 2022. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Cele S, Jackson L, Khoury DS, Khan K, Moyo-Gwete T, Tegally H, et al. (COMMIT-KZN Team) (February 2022). "Omicron extensively but incompletely escapes Pfizer BNT162b2 neutralization". Nature. 602 (7898): 654–656. Bibcode:2022Natur.602..654C. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04387-1. PMC 8866126. PMID 35016196. S2CID 245879254.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Callaway E (December 2021). "Omicron likely to weaken COVID vaccine protection". Nature. 600 (7889): 367–368. Bibcode:2021Natur.600..367C. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-03672-3. PMID 34880488. S2CID 245007078.

- ^ Arbel R, Hammerman A, Sergienko R, Friger M, Peretz A, Netzer D, et al. (December 2021). "BNT162b2 Vaccine Booster and Mortality Due to Covid-19". The New England Journal of Medicine. 385 (26): 2413–2420. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2115624. PMC 8728797. PMID 34879190.

- ^ Khoury DS, Steain M, Triccas J, Sigal A, Davenport MP (17 December 2021). "A meta-analysis of Early Results to predict Vaccine efficacy against Omicron". medRxiv 10.1101/2021.12.13.21267748.

- ^ Garcia-Beltran WF, St Denis KJ, Hoelzemer A, Lam EC, Nitido AD, Sheehan ML, et al. (December 2021). "mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine boosters induce neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant". medRxiv 10.1101/2021.12.14.21267755.

{{cite medRxiv}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Doria-Rose NA, Shen X, Schmidt SD, O'Dell S, McDanal C, Feng W, et al. (December 2021). "Booster of mRNA-1273 Strengthens SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Neutralization". medRxiv 10.1101/2021.12.15.21267805v2.

{{cite medRxiv}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Hansen CH, Schelde AB, Moustsen-Helms IR, Emborg HD, Krause TG, Mølbak K, et al. (Infectious Disease Preparedness Group at Statens Serum Institute) (23 December 2021). "Vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection with the Omicron or Delta variants following a two-dose or booster BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 vaccination series: A Danish cohort study". medRxiv 10.1101/2021.12.20.21267966.

- ^ Bar-On YM, Goldberg Y, Mandel M, Bodenheimer O, Freedman L, Alroy-Preis S, et al. (December 2021). "Protection against Covid-19 by BNT162b2 Booster across Age Groups". The New England Journal of Medicine. 385 (26): 2421–2430. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2115926. PMC 8728796. PMID 34879188.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Geddes L (29 November 2021). "What does appearance of Omicron variant mean for the double-vaccinated?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Omicron: what do we know about the new Covid variant? Archived 5 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian

- ^ "Boosters increase protection against death from Omicron in over-50s to 95% – UKHSA". The Guardian. 27 January 2022. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "COVID-19 vaccine surveillance report Week 4" (PDF). UK Health Security Agency. 27 January 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "Covid infections rising again across UK - ONS". BBC News. 11 March 2022. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "How soon after catching COVID-19 can you get it again?". ABC News. 2 May 2022. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Khan K, Karim F, Ganga Y, Bernstein M, Jule Z, Reedoy K, et al. (1 May 2022). "Omicron sub-lineages BA.4/BA.5 escape BA.1 infection elicited neutralizing immunity". medRxiv 10.1101/2022.04.29.22274477.

{{cite medRxiv}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Suryawanshi RK, Chen IP, Ma T, Syed AM, Brazer N, Saldhi P, et al. (May 2022). "Limited cross-variant immunity from SARS-CoV-2 Omicron without vaccination". Nature. 607 (7918): 351–355. Bibcode:2022Natur.607..351S. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04865-0. PMC 9279157. PMID 35584773. S2CID 248890159.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ "SARS-CoV-2 sequences by variant". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Huang P. "How monoclonal antibodies lost the fight with new COVID variants". NPR. Archived from the original on 15 August 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

External links

[edit]- A room, a bar and a classroom (visualization of how COVID-19 does and does not spread)