Helsinki

Helsinki

Helsingfors (Swedish) | |

|---|---|

| Helsingin kaupunki Helsingfors stad City of Helsinki | |

| Nicknames: | |

| |

| Coordinates: 60°10′15″N 24°56′15″E / 60.17083°N 24.93750°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| Sub-region | Helsinki sub-region |

| Metropolitan area | Helsinki metropolitan area |

| Charter | 12 June 1550 |

| Capital city | 8 April 1812 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Juhana Vartiainen (Kok) |

| • Governing body | City Council of Helsinki |

| Area (2018-01-01)[4] | |

| • Capital city | 715.48 km2 (276.25 sq mi) |

| • Land | 214.42 km2 (82.79 sq mi) |

| • Water | 501.74 km2 (193.72 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 680.12 km2 (262.60 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,698.99 km2 (1,428.19 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 26 m (85 ft) |

| Population (2023-12-31)[6] | |

| • Capital city | 674,500 |

| • Rank | Largest in Finland |

| • Density | 3,145.7/km2 (8,147/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,360,075 |

| • Urban density | 2,000/km2 (5,200/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,582,452 (metro) |

| • Metro density | 427.8/km2 (1,108/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | helsinkiläinen (Finnish) helsingforsare (Swedish) Helsinkian (English) |

| Population by native language | |

| • Finnish | 75% (official) |

| • Swedish | 5.5% (official) |

| • Others | 19.6% |

| Population by age | |

| • 0 to 14 | 14.3% |

| • 15 to 64 | 68.3% |

| • 65 or older | 17.4% |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+03:00 (EEST) |

| Area code | +358-9 |

| Climate | Dfb |

| Website | www |

Helsinki[a][b] is the capital and most populous city in Finland. It is located on the shore of the Gulf of Finland and serves as the seat of the Uusimaa region in southern Finland. Approximately 675,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.25 million in the capital region, and 1.58 million in the metropolitan area. As the most populous urban area in Finland, it is the country's most significant centre for politics, education, finance, culture, and research. Helsinki is situated 80 kilometres (50 mi) to the north of Tallinn, Estonia, 360 kilometres (220 mi) to the north of Riga, Latvia, 400 kilometres (250 mi) to the east of Stockholm, Sweden, and 300 kilometres (190 mi) to the west of Saint Petersburg, Russia. Helsinki has significant historical connections with these four cities.

Together with the cities of Espoo, Vantaa and Kauniainen – and surrounding commuter towns,[10] including the neighbouring municipality of Sipoo to the east[11] – Helsinki forms the metropolitan area. This area is often considered Finland's only metropolis and is the world's northernmost metropolitan area with over one million inhabitants. Additionally, it is the northernmost capital of an EU member state. Helsinki is the third largest municipality in the Nordic countries, following Stockholm and Oslo. Its urban area is the second largest in the Nordic countries, after Stockholm. Helsinki Airport, located in the neighbouring city of Vantaa, serves the city with frequent flights to numerous destinations in Europe, North America, and Asia.

Helsinki is a bilingual municipality with Finnish and Swedish as its official languages. The population consists of 75% Finnish speakers, 5% Swedish speakers, and 20% speakers of other languages, which is well above the national average.

Helsinki hosted the 1952 Summer Olympics, the first CSCE/OSCE Summit in 1975, the first World Athletics Championships in 1983, the 52nd Eurovision Song Contest in 2007 and it was the 2012 World Design Capital.[12]

Helsinki has one of the highest standards of urban living in the world. In 2011, the British magazine Monocle ranked Helsinki as the world's most liveable city in its liveable cities index.[13] In the Economist Intelligence Unit's 2016 liveability survey, Helsinki ranked ninth out of 140 cities.[14] In July 2021, the American magazine Time named Helsinki as one of the world's greatest places in 2021, as a city that "can grow into a burgeoning cultural nest in the future" and that is already known as an environmental pioneer in the world.[15] In an international Cities of Choice survey conducted in 2021 by the Boston Consulting Group and the BCG Henderson Institute, Helsinki was ranked the third best city in the world to live in, with London and New York City coming in first and second.[16][17] In the Condé Nast Traveler magazine's 2023 Readers' Choice Awards, Helsinki was ranked 4th as the friendliest cities in Europe.[18] Helsinki, along with Rovaniemi in Lapland, is also one of Finland's most important tourist cities.[19] Due to the large number of sea passengers per year, Helsinki is classified as a major port city,[20] and in 2017 it was rated the world's busiest passenger port.[21]

Etymology[edit]

According to a theory put forward in the 1630s, at the time of Swedish colonisation of the Finnish coast, colonists from Hälsingland in central Sweden arrived at what is now the Vantaa River and called it Helsingå ('Helsinge River'), giving rise to the names of the village and church of Helsinge in the 1300s.[22] This theory is questionable, as dialect research suggests that the settlers came from Uppland and the surrounding areas.[23] Others have suggested that the name derives from the Swedish word helsing, an archaic form of the word hals ('neck'), which refers to the narrowest part of a river, the rapids.[24] Other Scandinavian towns in similar geographical locations were given similar names at the time, such as Helsingør in Denmark and Helsingborg in Sweden.

When a town was founded in the village of Forsby (later Koskela) in 1548, it was called Helsinge fors, 'Helsinge rapids'. The name refers to the Vanhankaupunginkoski rapids at the mouth of the river.[25] The town was commonly known as Helsinge or Helsing, from which the modern Finnish name is derived.[26]

Official Finnish government documents and Finnish language newspapers have used the name Helsinki since 1819, when the Senate of Finland moved to the city from Turku, the former capital of Finland. Decrees issued in Helsinki were dated with Helsinki as the place of issue. This is how the form Helsinki came to be used in written Finnish.[27] When Finland became a Grand Duchy of Finland, an autonomous state under the rule of the Russian Empire, Helsinki was known as Gel'singfors (Гельсингфорс) in Russian, because the main and official language of Grand Duchy of Finland was Swedish.

In Helsinki slang, the city is called Stadi (from the Swedish word stad, meaning 'city'). Abbreviated form Hesa is equally common, but its use is associated with people of rural origin ("junantuomat", lit. "brought by a train") and frowned upon by locals.[1][28] Helsset is the Northern Sami name for Helsinki.[29]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

After the end of the Ice Age and the retreat of the ice sheet, the first settlers arrived in the Helsinki area around 5000 BC. Their presence has been documented by archaeologists in Vantaa, Pitäjänmäki and Kaarela.[30] Permanent settlements did not appear until the beginning of the 1st millennium AD, during the Iron Age, when the area was inhabited by the Tavastians. They used the area for fishing and hunting, but due to the lack of archaeological finds it is difficult to say how extensive their settlements were. Pollen analysis has shown that there were agricultural settlements in the area in the 10th century, and surviving historical records from the 14th century describe Tavastian settlements in the area.[31]

Christianity does not gain a significant foothold in Finland before the 11th century. After that, a number of crosses and other objects related to Christianity can be found in archaeological material. According to the traditional view, the Kingdom of Sweden made three crusades to Finland, thanks to which the region was incorporated into both Christianity and the Swedish Empire. Recent research has shown that these expeditions, to the extent that there were even three of them, were not the crusades that had been imagined. Later, the conquest of Finland was justified in terms of "civilisation" and "christianisation", and the myth of the Crusades was developed. It is more likely that it was a multidimensional combination of economic, cultural and political power ambitions.[32]

The early settlements were raided by Vikings until 1008, and the Battle at Herdaler was a battle between the Norse Viking leader Olav Haraldsson (later King Olaf II of Norway, also known as Saint Olaf) and local Finns at Herdaler (now Ingå), not far from Helsinga, around 1007-8.[33] The Saga of Olaf Haraldson tells how Olav raided the coasts of Finland and was almost killed in battle. He ran away in fear and after that the Vikings did not raid the coasts of Finland.[34][35]

Later the area was settled by Christians from Sweden. They came mainly from the Swedish coastal regions of Norrland and Hälsingland, and their migration intensified around 1100.[30] The Swedes permanently colonised the Helsinki region's coastline in the late 13th century, after the successful 'crusade' to Finland that led to the defeat of the Tavastians.[36][31]

In the Middle Ages, the Helsinki area was a landscape of small villages. Some of the old villages from the 1240s in the area of present-day Helsinki, such as Koskela and Töölö, are now Helsinki districts, as are the rest of the 27 medieval villages. The area gradually became part of the Kingdom of Sweden and Christianity. Suuri Rantatie, or the King's Road, ran through the area and two interesting medieval buildings were built here: Vartiokylä hillfort in the 1380s and the Church of St. Lawrence in 1455. In the Middle Ages, several thousand people lived in Helsinki's keep.[37]

There was a lot of trade across the Baltic Sea. The shipping route to the coast, and especially to Reval, meant that by the end of the Middle Ages the Helsinki region had become an important trading centre for wealthy peasants, priests and nobles in Finland, after Vyborg and Pohja. Furs, wood, tar, fish and animals were exported from Helsinki, and salt and grain were brought to the fortress. Helsinki was also the most important cattle-breeding area in Uusimaa. With the help of trade, Helsinki became one of the wealthiest cities in Finland and Uusimaa. Thanks to trade and travel, e.g. to Reval, people could speak several languages, at least helpfully. Depending on the situation, Finnish, Swedish, Latin or Low German could be heard in the Helsinki area.[38]

Written chronicles from 1417 mention the village of Koskela near the rapids at the mouth of the River Vantaa, where Helsinki was to be founded.[30]

Founding of Helsinki[edit]

Helsinki was founded by King Gustav I of Sweden on 12 June 1550 as a trading town called Helsingfors to rival the Hanseatic city of Reval (now Tallinn) on the southern shore of the Gulf of Finland.[39][30] To populate the new town at the mouth of the Vantaa River, the king ordered the bourgeoisie of Porvoo, Raseborg, Rauma and Ulvila to move there.[40] The shallowness of the bay made it impossible to build a harbour, and the king allowed the settlers to leave the unfortunate location. In 1640, Count Per Brahe the Younger, together with some descendants of the original settlers, moved the centre of the city to the Vironniemi peninsula by the sea, today's Kruununhaka district, where the Senate Square and Helsinki Cathedral are located.[41]

During the second half of the 17th century, Helsinki, as a wooden city, suffered from regular fires, and by the beginning of the 18th century the population had fallen below 1,700. For a long time Helsinki was mainly a small administrative town for the governors of Nyland and Tavastehus County, but its importance began to grow in the 18th century when plans were made to build a more solid naval defence in front of the city.[40] Little came of these plans, however, as Helsinki remained a small town plagued by poverty, war and disease. The plague of 1710 killed most of Helsinki's population.[39] After the Russians captured Helsinki in May 1713 during the Great Northern War, the retreating Swedish administration set fire to parts of the city.[42][43] Despite this, the city's population grew to 3,000 by the beginning of the 19th century. The construction of the naval fortress of Sveaborg (Viapori in Finnish, now also called Suomenlinna) in the 18th century helped to improve Helsinki's status. However, it wasn't until Russia defeated Sweden in the Finnish War and annexed Finland as the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland in 1809 that the city began to develop into a substantial city. The Russians besieged the Sveaborg fortress during the war, and about a quarter of the city was destroyed in a fire in 1808.[44]

Emperor Alexander I of Russia moved the capital of Finland from Turku to Helsinki on 8 April 1812 to reduce Swedish influence in Finland and bring the capital closer to St Petersburg.[45][46][47] After the Great Fire of Turku in 1827, the Royal Academy of Turku, the only university in the country at the time, was also moved to Helsinki and eventually became the modern University of Helsinki. The move consolidated the city's new role and helped set it on a path of continuous growth. This transformation is most evident in the city centre, which was rebuilt in the neoclassical style to resemble St. Petersburg, largely according to a plan by the German-born architect C. L. Engel. As elsewhere, technological advances such as the railway and industrialisation were key factors in the city's growth.

Twentieth century[edit]

By the 1910s, Helsinki's population was already over 100,000, and despite the turbulence of Finnish history in the first half of the 20th century, Helsinki continued to grow steadily. This included the Finnish Civil War and the Winter War, both of which left their mark on the city. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were roughly equal numbers of Finnish and Swedish speakers in Helsinki; the majority of workers were Finnish-speaking. The local Helsinki slang (or stadin slangi) developed among Finnish children and young people from the 1890s as a mixed Finnish-Swedish language, with influences from German and Russian, and from the 1950s the slang began to become more Finnish.[48] A landmark event was the 1952 Olympic Games, which were held in Helsinki. Finland's rapid urbanisation in the 1970s, which occurred late compared to the rest of Europe, tripled the population of the metropolitan area, and the Helsinki Metro subway system was built.

Geography[edit]

Known as the "Daughter of the Baltic"[2] or the "Pearl of the Baltic",[3][49] Helsinki is located at the tip of a peninsula and on 315 islands. The city centre is located on a southern peninsula, Helsinginniemi ("Cape of Helsinki"), which is rarely referred to by its actual name, Vironniemi ("Cape of Estonia"). Population density is comparatively high in certain parts of downtown Helsinki, reaching 16,494 inhabitants per square kilometre (42,720/sq mi) in the district of Kallio, overall Helsinki's population density is 3,147 per square kilometre. Outside the city centre, much of Helsinki consists of post-war suburbs separated by patches of forest. A narrow, 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) long Helsinki Central Park, which stretches from the city centre to Helsinki's northern border, is an important recreational area for residents. The City of Helsinki has about 11,000 boat moorings and over 14,000 hectares (35,000 acres; 54 square miles) of marine fishing waters adjacent to the capital region. About 60 species of fish are found in this area, and recreational fishing is popular.

Helsinki's main islands include Seurasaari, Lauttasaari and Korkeasaari – the latter is home to Finland's largest zoo, Korkeasaari Zoo. The former military islands of Vallisaari and Isosaari are now open to the public, but Santahamina is still in military use. The most historic and remarkable island is the fortress of Suomenlinna (Sveaborg). The island of Pihlajasaari is a popular summer resort for gays and naturists, comparable to Fire Island in New York City.

There are 60 nature reserves in Helsinki with a total area of 95,480 acres (38,640 ha). Of the total area, 48,190 acres (19,500 ha) are water areas and 47,290 acres (19,140 ha) are land areas. The city also has seven nature reserves in Espoo, Sipoo, Hanko and Ingå. The largest nature reserve is the Vanhankaupunginselkä, with an area of 30,600 acres (12,400 ha). The city's first nature reserve, Tiiraluoto of Lauttasaari, was established in 1948.[50]

Helsinki's official plant is the Norway maple and its official animal is the red squirrel.[51]

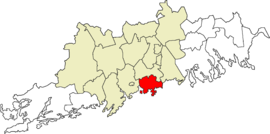

Metropolitan area[edit]

The Helsinki capital region (Finnish: Pääkaupunkiseutu, Swedish: Huvudstadsregionen) comprises four municipalities: Helsinki, Espoo, Vantaa, and Kauniainen.[52] The Helsinki urban area is considered to be the only metropolis in Finland.[53] It has a population of about 1.25 million, and is the most densely populated area of Finland. The Capital Region spreads over a land area of 770 square kilometres (300 sq mi) and has a population density of 1,619 per sg km. With over 20 percent of the country's population in just 0.2 percent of its surface area, the area's housing density is high by Finnish standards.

The Helsinki metropolitan area or the Greater Helsinki consists of the cities of the capital region and ten surrounding municipalities: Hyvinkää, Järvenpää, Kerava, Kirkkonummi, Nurmijärvi, Sipoo, Tuusula, Pornainen, Mäntsälä and Vihti.[54] The Metropolitan Area covers 3,697 square kilometres (1,427 sq mi) and has a population of about 1.58 million, or about a fourth of the total population of Finland. The metropolitan area has a high concentration of employment: approximately 750,000 jobs.[55] Despite the intensity of land use, the region also has large recreational areas and green spaces. The Helsinki metropolitan area is the world's northernmost urban area with a population of over one million people, and the northernmost EU capital city.

The Helsinki urban area is an officially recognized urban area in Finland, defined by its population density. The area stretches throughout 11 municipalities, and is the largest such area in Finland, with a land area of 669.31 square kilometres (258.42 sq mi) and approximately 1.36 million inhabitants.

Climate[edit]

Helsinki has a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb).[56] Due to the moderating influence of the Baltic Sea and the North Atlantic Current (see also Extratropical cyclone), winter temperatures are higher than the northern location would suggest, with an average of −4 °C (25 °F) in January and February.[57]

Winters in Helsinki are significantly warmer than in the north of Finland, and the snow season in the capital is much shorter due to its location in the extreme south of Finland and the urban heat island effect. Temperatures below −20 °C (−4 °F) occur only a few times a year. However, due to the latitude, the days around the winter solstice are 5 hours and 48 minutes long, with the sun very low (at noon the sun is just over 6 degrees in the sky), and the cloudy weather at this time of year exacerbates the darkness. Conversely, Helsinki enjoys long days in summer, with 18 hours and 57 minutes of daylight around the summer solstice.[58]

The average maximum temperature from June to August is around 19 to 22 °C (66 to 72 °F). Due to the sea effect, especially on hot summer days, daytime temperatures are slightly cooler and nighttime temperatures higher than further inland. The highest temperature recorded in the city was 33.2 °C (91.8 °F) on 28 July 2019 at the Kaisaniemi weather station,[59] breaking the previous record of 33.1 °C (91.6 °F) set in July 1945 at the Ilmala weather station.[60] The lowest temperature recorded in the city was −34.3 °C (−29.7 °F) on 10 January 1987, although an unofficial low of −35 °C (−31 °F) was recorded in December 1876.[61] Helsinki Airport (in Vantaa, 17 km north of Helsinki city centre) recorded a maximum temperature of 33.7 °C (92.7 °F) on 29 July 2010 and a minimum of −35.9 °C (−33 °F) on 9 January 1987. Precipitation comes from frontal passages and thunderstorms. Thunderstorms are most common in summer.

| Climate data for Central Helsinki (Kaisaniemi) 1991–2020 normals, records 1900–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

31.7 (89.1) |

33.2 (91.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

26.2 (79.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

33.2 (91.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

8.1 (46.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

9.2 (48.6) |

4.4 (39.9) |

1.4 (34.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

4.4 (39.9) |

10.4 (50.7) |

14.9 (58.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

12.3 (54.1) |

6.6 (43.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −5.6 (21.9) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

1.1 (34.0) |

6.4 (43.5) |

11.2 (52.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

4.2 (39.6) |

0.4 (32.7) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −34.3 (−29.7) |

−31.5 (−24.7) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

5.4 (41.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−11.6 (11.1) |

−18.6 (−1.5) |

−29.5 (−21.1) |

−34.3 (−29.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 53 (2.1) |

38 (1.5) |

34 (1.3) |

34 (1.3) |

38 (1.5) |

60 (2.4) |

57 (2.2) |

81 (3.2) |

56 (2.2) |

73 (2.9) |

69 (2.7) |

58 (2.3) |

653 (25.7) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 19 | 16 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 19 | 176 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 37.2 | 70.6 | 139.5 | 195.0 | 285.2 | 297.0 | 291.4 | 238.7 | 150.0 | 93.0 | 36.0 | 27.9 | 1,861.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 1.2 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 9.2 | 9.9 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 5 | 3 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 5.1 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 6.8 | 9.2 | 11.8 | 14.6 | 17.2 | 18.8 | 18.0 | 15.6 | 12.9 | 10.1 | 7.5 | 6.0 | 12.4 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 18 | 27 | 38 | 45 | 53 | 53 | 52 | 49 | 39 | 30 | 16 | 15 | 36 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Source 1: FMI climatological normals for Finland 1991–2020,[62] record highs and lows[63] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (sun data)[64] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Helsinki Kumpula (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 35 | 71 | 146 | 203 | 296 | 278 | 308 | 248 | 160 | 89 | 34 | 23 | 1,890 |

| Source: https://ilmatieteenlaitos.fi/1991-2020-auringonpaiste-ja-sateilytilastot | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Helsinki Airport (Vantaa) 1991–2020 normals, records 1952–present |

|---|

Neighbourhoods and other subdivisions[edit]

Helsinki is divided into three major areas: Helsinki Downtown (Finnish: Helsingin kantakaupunki, Swedish: Helsingfors innerstad), North Helsinki (Finnish: Pohjois-Helsinki, Swedish: Norra Helsingfors) and East Helsinki (Finnish: Itä-Helsinki, Swedish: Östra Helsingfors). Of these, Helsinki Downtown means the undefined core area of capital, as opposed to suburbs. The designations business center and city center usually refer to Kluuvi, Kamppi and Punavuori.[67][68] Other subdivisional centers outside the downtown area include Malmi (Swedish: Malm),[69][70] located in the northeastern part of city, and Itäkeskus (Swedish: Östra centrum),[71] in the eastern part of city.

Cityscape[edit]

Neoclassical and romantic nationalism trend[edit]

Carl Ludvig Engel, appointed to plan a new city centre on his own, designed several neoclassical buildings in Helsinki. The focal point of Engel's city plan was the Senate Square. It is surrounded by the Government Palace (to the east), the main building of Helsinki University (to the west), and (to the north) the large Helsinki Cathedral, which was finished in 1852, twelve years after Engel's death. Helsinki's epithet, "The White City of the North", derives from this construction era. Most of Helsinki's older buildings were built after the 1808 fire; before that time, the oldest surviving building in the center of Helsinki is the Sederholm House (1757) at the intersection of Senate Square and the Katariinankatu street.[41] Suomenlinna also has buildings completed in the 18th century, including the Kuninkaanportti on the Kustaanmiekka Island (1753–1754).[72] The oldest church in Helsinki is the Östersundom church, built in 1754.[73]

Helsinki is also home to numerous Art Nouveau-influenced (Jugend in Finnish) buildings belonging to the Kansallisromantiikka (romantic nationalism) trend, designed in the early 20th century and strongly influenced by Kalevala, which was a common theme of the era. Helsinki's Art Nouveau style is also featured in central residential districts, such as Katajanokka and Ullanlinna.[74] An important architect of the Finnish Art Nouveau style was Eliel Saarinen, whose architectural masterpiece was the Helsinki Central Station. Opposite the Bank of Finland building is the Renaissance Revivalish the House of the Estates (1891).[75]

The only visible public buildings of the Gothic Revival architecture in Helsinki are St. John's Church (1891) in Ullanlinna, which is the largest stone church in Finland, and its twin towers rise to 74 meters and have 2,600 seats.[76] Other examples of neo-Gothic include the House of Nobility in Kruununhaka and the Catholic St. Henry's Cathedral.[77][78]

In addition to other cities in Northern Europe that were not under the Soviet Union, such as Stockholm, Sweden, Helsinki's neoclassical buildings gained also popularity as a backdrop for scenes intended to depict the Soviet Union in numerous Hollywood movies during the Cold War era, when filming within the actual USSR was not possible. Some of them, including The Kremlin Letter (1970), Reds (1981), and Gorky Park (1983).[79] was possible due to such Russian cities as Leningrad and Moscow also having similar neoclassical architecture. At the same time due to Cold War and Finnish relations with the USSR the government secretly instructed Finnish officials not to extend assistance to such film projects.[80] There are some films where Helsinki has been represented on its own in films, most notably the 1967 British-American espionage thriller Billion Dollar Brain, starring Michael Caine.[81][82] The city has large amounts of underground areas such as shelters and tunnels, many used daily as swimming pool, church, water management, entertainment etc.[83][84][85]

Functionalism and modern architecture[edit]

Helsinki also features several buildings by Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, recognized as one of the pioneers of architectural functionalism. However, some of his works, such as the headquarters of the paper company Stora Enso and the concert venue Finlandia Hall, have been subject to divided opinions from the citizens.[86][87][88]

Functionalist buildings in Helsinki by other architects include the Olympic Stadium, the Tennis Palace, the Rowing Stadium, the Swimming Stadium, the Velodrome, the Glass Palace, the Töölö Sports Hall, and Helsinki-Malmi Airport. The sports venues were built to serve the 1940 Helsinki Olympic Games; the games were initially cancelled due to the Second World War, but the venues fulfilled their purpose in the 1952 Olympic Games. Many of them are listed by DoCoMoMo as significant examples of modern architecture. The Olympic Stadium and Helsinki-Malmi Airport are also catalogued by the Finnish Heritage Agency as cultural-historical environments of national significance.[89][90]

When Finland became heavily urbanized in the 1960s and 1970s, the district of Pihlajamäki, for example, was built in Helsinki for new residents, where for the first time in Finland, precast concrete was used on a large scale. Pikku Huopalahti, built in the 1980s and 1990s, has tried to get rid of a one-size-fits-all grid pattern, which means that its look is very organic and its streets are not repeated in the same way. Itäkeskus in Eastern Helsinki was the first regional center in the 1980s.[91] Efforts have also been made to protect Helsinki in the late 20th century, and many old buildings have been renovated.[91] Modern architecture is represented, for example, by the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, which consists of two straight and curved-walled parts, though this style strongly divided the opinions from the citizens.[88] Next to Kiasma is the glass-walled Sanomatalo (1999).

There have been many plans to build highrise buildings in Helsinki since the 1920s when architect Eliel Saarinen proposed a 85 meters tall Kalevalatalo in 1921.[92] In 1924 Oiva Kallio won Etu-Töölö competition with his plan (several 14- to 16-story buildings).[93] A 32-story cityhall was also proposed.[94] In other plans in the 1930s e.g.18-story Kino palace, 17-story apartment building, and 30-story [95] Stockmann were proposed but only the 70 meters tall 14-story hotel Torni was built.[96] It was the tallest high-rise in Finland until 1976 when 83 meters tall Neste torni was topped out. Helsinki had rejected the tower.[97] Twin 30-story buildings were proposed in Pasila in the 1970s but were rejected.[95] Later in the 1960s 150 meters tall Flatscreen and four 24-story office buildings in Hakaniemi were cancelled. In 1990 104 meters tall Kone building [98][99] was also cancelled. In pasila, a 120 meters tall 35-story Leijona- torni was proposed in 2011 but it was cancelled few years later.[100][101] In 2020, a 30-story wooden high-rise was planned in Pasila.[102]

2015 a plan called Trigoni[103] was proposed, consisting of ten skyscrapers for the Central Pasila, former lake area [104] near the Mall of Tripla shopping centre. The highest of which was to become about 200 metres (660 ft) high. The project was abandoned in 2021.[105]

The start of the 21st century marked the beginning of highrise construction in Helsinki, when the city decided to allow the construction of skyscrapers. In Kalasatama, the first 35-story 131,4 meters tall Majakka, 32-story (122 m (400 ft); Loisto and 31-story (120 m) Lumo[106] residential towers are already completed. 111 meters tall office building Horisontti is under construction. Later they will be joined by a 37-story (137 m) 32-story (122 m),[107] 27-story, and 24-story residential buildings.[108]

A new plan "Etelä-Pasila" in Läntinen (western) Tornialue has been proposed, consisting of a 29-story office building, 28-story residential building and two lower skyscrapers. Their construction will begin in 2026.[109] Over 130 meters tall 32-story office building in Keskinen Tornialue is under construction,[110] and 3 (or 4) 26-31-story towers will be built in Itäinen (eastern) Tornialue.[111] Also a 33-story hotel Pasila has been approved.[112] Nearby another over 100 meters tall 27-story hotel has been planned.[113]

In Vuosaari, a 33-story, 26-story, and 24-story residential buildings have been built in 2023.[114] In Jätkäsaari, a 113 meters tall hotel and a 24-story residential tower have been approved[115] In Ruoholahti, a 29-story and 24-story office buildings will be 121 and 93 meters tall.[116] Well over 200 hundred high-rise buildings will be built in Helsinki in the 2020s.[117]

Statues and sculptures[edit]

Well-known statues and monuments strongly embedded in the cityscape of Helsinki include the Keisarinnankivi ("Stone of the Empress", 1835), the statue of Russian Emperor Alexander II (1894), the fountain sculpture Havis Amanda (1908), the Paavo Nurmi statue (1925), the Three Smiths Statue (1932), the Aleksis Kivi Memorial (1939), the Eino Leino Statue (1953), the Equestrian statue of Marshal Mannerheim (1960) and the Sibelius Monument (1967).[119]

Government[edit]

As is the case with all Finnish municipalities, Helsinki's city council is the main decision-making organ in local politics, dealing with issues such as urban planning, schools, health care, and public transport. The council is chosen in the nationally held municipal elections, which are held every four years.

Helsinki's city council consists of eighty-five members. Following the most recent municipal elections in 2017, the three largest parties are the National Coalition Party (25), the Green League (21), and the Social Democratic Party (12).[120]

The Mayor of Helsinki is Juhana Vartiainen.

Demographics[edit]

Population[edit]

The city of Helsinki has 674,500 inhabitants, making it the most populous municipality in Finland and the third in the Nordics. The Helsinki region is the largest urbanised area in Finland with 1,582,452 inhabitants. The city of Helsinki is home to 12% of Finland's population. 19.9% of the population has a foreign background, which is twice above the national average. However, it is lower than in the major Finnish cities of Espoo or Vantaa.[122]

At 53 percent of the population, women form a greater proportion of Helsinki residents than the national average of 51 percent. Helsinki's population density of 3,147 people per square kilometre makes Helsinki the most densely-populated city in Finland. The life expectancy for men and women is slightly below the national averages: 75.1 years for men as compared to 75.7 years, 81.7 years for women as compared to 82.5 years.[123][124]

Helsinki has experienced strong growth since the 1810s, when it replaced Turku as the capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland, which later became the sovereign Republic of Finland. The city continued its growth from that time on, with an exception during the Finnish Civil War. From the end of World War II up until the 1970s there was a massive exodus of people from the countryside to the cities of Finland, in particular Helsinki. Between 1944 and 1969 the population of the city nearly doubled from 275,000[125] to 525,600.[126]

In the 1960s, the population growth of Helsinki began to decrease, mainly due to a lack of housing.[127] Some residents began to move to the neighbouring cities of Espoo and Vantaa, resulting in increased population growth in both municipalities. Espoo's population increased ninefold in sixty years, from 22,874 people in 1950 to 244,353 in 2009.[128] Vantaa saw an even more dramatic change in the same time span: from 14,976 in 1950 to 197,663 in 2009, a thirteenfold increase. These population changes prompted the municipalities of metropolitan area into more intense cooperation in areas such as public transportation[129] – resulting in the foundation of HSL – and waste management.[130] The increasing scarcity of housing and the higher costs of living in the capital region have pushed many daily commuters to find housing in formerly rural areas, and even further, to cities such as Lohja, Hämeenlinna, Lahti, and Porvoo.

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1980 | 483,036

|

| 1985 | 485,795

|

| 1990 | 492,795

|

| 1995 | 525,031

|

| 2000 | 555,474

|

| 2005 | 560,905

|

| 2010 | 588,549

|

| 2015 | 628,208

|

| 2020 | 656,920

|

Language[edit]

Population by mother tongue (2023)[122]

The city of Helsinki is officially bilingual, with both Finnish and Swedish as official languages. In 2023, the majority of the population, 75%, spoke Finnish as their mother tongue. There were 36,844 Swedish speakers, or 5.5% of the population. The number of people who speak Sámi, Finland's third official language, is only 68 inhabitants. In Helsinki, 19.6% of the population speak a mother tongue other than Finnish or Swedish.[122] As English and Swedish are compulsory school subjects, functional bilingualism or trilingualism acquired through language studies is not uncommon.

Although few people speak the Sámi languages as their mother tongue, there are 527 people of Sami origin.[131] There are 93 Tatar speakers in Helsinki, almost half of the total number of Tatar speakers in Finland.

Helsinki slang is a regional dialect of the city. Historically, it was a combination of Finnish and Swedish, with influences from Russian and German. Nowadays it has a strong English influence. Today, however, Finnish is the common language of communication between Finnish speakers, Swedish speakers and speakers of other languages (New Finns) in everyday public life between strangers.[132][133]

The city of Helsinki and the national authorities have specifically targeted Swedish speakers. Knowledge of Finnish is essential in business and is usually a basic requirement in the labour market.[134] Swedish speakers are most concentrated in the southern parts of the city. The district with the most Swedish speakers is Ullanlinna/Ulrikasborg with 2,098 (19.6%), while Byholmen is the only district where Swedish is the majority language (at 82.8%). The number of Swedish speakers decreased every year until 2008, and has increased every year since then. Since 2007, the number of Swedish speakers has increased by 2,351.[135] In 1890, Finnish speakers overtook Swedish speakers to become the majority of the city's population.[136] At that time, the population of Helsinki was 61,530.[137]

The number of people with a foreign mother tongue is expected to reach 196,500 in 2035, representing 26% of the population. 114,000 will speak non-European languages, or 15% of the population.[138] Today, at least 160 different languages are spoken in Helsinki. The most common foreign languages are Russian (3.1%), Somali (2.1%), Arabic (1.5%), English (1.5%) and Estonian (1.4%).[122]

Immigration[edit]

| Population by country of birth (2023)[122] | ||

| Nationality | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| 556,372 | 82.5 | |

| 14,430 | 2.1 | |

| 10,223 | 1.5 | |

| 7,341 | 1.1 | |

| 6,163 | 0.9 | |

| 4,363 | 0.6 | |

| 4,343 | 0.6 | |

| 3,591 | 0.5 | |

| 3,055 | 0.5 | |

| 3,019 | 0.4 | |

| 2,677 | 0.4 | |

| Other | 49,573 | 7.3 |

As of 2023[update], there were 134,084 people with an immigrant background living in Helsinki, or 19.9% of the population.[c] There were 118,128 residents who were born abroad, or 17.5% of the population. The number of foreign citizens in Helsinki was 79,992.[122]

The relative share of immigrants in Helsinki's population is twice the national average, and the city's new residents are increasingly of foreign origin.[122] This will increase the proportion of foreign residents in the coming years. As a crossroads of many international ports and Finland's largest airport, Helsinki is the global gateway to and from Finland.

Most foreign-born citizens come from the former Soviet Union, Estonia, Somalia, Iraq, and Russia.[122]

Religion[edit]

In 2023, the Evangelical Lutheran Church was the largest religious group with 46.1% of the Helsinki population. Other religious groups made up 4.5% of the population. 49.4% of the population had no religious affiliation.[140]

The most important churches in Helsinki are Helsinki Cathedral (1852), Uspenski Cathedral (1868), St. John's Church (1891), Kallio Church (1912) and Temppeliaukio Church (1969).

There are 21 Lutheran congregations in Helsinki, 18 of which are Finnish-speaking and 3 are Swedish-speaking. These form Helsinki's congregationgroup. Outside that there is Finland's German congregation with 3,000 members and Rikssvenska Olaus Petri-församlingen for Swedish-citizens with 1,000 members.[141]

The largest Orthodox congregation is the Orthodox Church of Helsinki. It has 20,000 members. Its main church is the Uspenski Cathedral.[142] The two largest Catholic congregations are the Cathedral of Saint Henry, with 4,552 members, established in 1860 and St Mary's Catholic Parish, with 4,107 members, established in 1954.[143]

There are around 30 mosques in the Helsinki region. Many linguistic and ethnic groups such as Bangladeshis, Kosovars, Kurds and Bosniaks have established their own mosques.[144] The largest congregation in both Helsinki and Finland is the Helsinki Islamic Center, established in 1995. It has over 2,800 members as of 2017[update], and it received €24,131 in government assistance.[145]

In 2015, imam Anas Hajar estimated that on big celebrations around 10,000 Muslims visit mosques.[146] In 2004, it was estimated that there were 8,000 Muslims in Helsinki, 1.5% of the population at the time.[147] The number of people in Helsinki with a background from Muslim majority countries was nearly 41,000 as of 2021, representing over 6% of the population.

The main synagogue of Helsinki is the Helsinki Synagogue from 1906, located in Kamppi. It has over 1,200 members, out of the 1,800 Jews in Finland, and it is the older of the two buildings in Finland originally built as a synagogue, followed by the Turku Synagogue in 1912.[148] The congregation includes a synagogue, Jewish kindergarten, school, library, Jewish meat shop, two Jewish cemeteries and an retirement home. Many Jewish organizations and societies are based there, and the synagogue publishes the main Jewish magazine in Finland, HaKehila.[149]

Economy[edit]

Helsinki metropolitan area generates approximately one third of Finland's GDP. GDP per capita is roughly 1.3 times the national average.[150] Helsinki profits on serviced-related IT and public sectors. Having moved from heavy industrial works, shipping companies also employ a substantial number of people.[151]

The metropolitan area's gross value added per capita is 200% of the mean of 27 European metropolitan areas, equalling those of Stockholm and Paris. The gross value added annual growth has been around 4%.[152]

83 of the 100 largest Finnish companies have their headquarters in the metropolitan area. Two-thirds of the 200 highest-paid Finnish executives live in the metropolitan area and 42% in Helsinki. The average income of the top 50 earners was 1.65 million euro.[153]

The tap water is of excellent quality and it is supplied by the 120 km (75 mi) Päijänne Water Tunnel, one of the world's longest continuous rock tunnels.[154]

Education[edit]

Helsinki has 190 comprehensive schools, 41 upper secondary schools, and 15 vocational institutes. Half of the 41 upper secondary schools are private or state-owned, the other half municipal. There are two major research universities in Helsinki, the University of Helsinki and Aalto University, and a number of other higher level institutions and polytechnics which focus on higher-level professional education.

Research universities[edit]

Other institutions of higher education[edit]

- Hanken School of Economics

- University of the Arts Helsinki

- National Defence University

- Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences

- Laurea University of Applied Sciences

- Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences

- Arcada University of Applied Sciences

- Diaconia University of Applied Sciences

- HUMAK University of Applied Sciences

Helsinki is one of the co-location centres of the Knowledge and Innovation Community (Future information and communication society) of The European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT).[155]

Culture[edit]

Museums[edit]

The biggest historical museum in Helsinki is the National Museum of Finland, which displays a vast collection from prehistoric times to the 21st century. The museum building itself, a national romantic-style neomedieval castle, is a tourist attraction. Another major historical museum is the Helsinki City Museum, which introduces visitors to Helsinki's 500-year history. The University of Helsinki also has many significant museums, including the Helsinki University Museum "Arppeanum" and the Finnish Museum of Natural History.

The Finnish National Gallery consists of three museums: Ateneum Art Museum for classical Finnish art, Sinebrychoff Art Museum for classical European art, and Kiasma Art Museum for modern art, in a building by architect Steven Holl. The old Ateneum, a neo-Renaissance palace from the 19th century, is one of the city's major historical buildings. All three museum buildings are state-owned through Senate Properties.

The city of Helsinki hosts its own art collection in the Helsinki Art Museum (HAM), primarily located in its Tennispalatsi gallery. Around 200 pieces of public art lie outside. The art is all city property.

Helsinki Art Museum will in 2020 launch the Helsinki Biennial, which will bring art to maritime Helsinki – in its first year to the island of Vallisaari.[156]

The Design Museum is devoted to the exhibition of both Finnish and foreign design, including industrial design, fashion, and graphic design. Other museums in Helsinki include the Military Museum of Finland, Didrichsen Art Museum, Amos Rex Art Museum, and the Tram Museum.

- Museums in Helsinki

-

Sinebrychoff Art Museum (1842)

-

Helsinki University Museum "Arppeanum" (1869)

-

The Cygnaeus Gallery Museum (1870)

-

The Mannerheim Museum (1874; 1957 as museum)

-

The Military Museum of Finland (1881)

-

Classical art museum Ateneum (1887)

-

The Design Museum (1894)

-

Tram Museum (Ratikkamuseo) (1900)

-

The National Museum of Finland (1910)

-

The Helsinki City Museum (1911)

-

The Finnish Museum of Natural History (1913)

-

Kunsthalle Helsinki art venue (1928)

-

Didrichsen Art Museum (1964)

-

Helsinki Art Museum (1968)

-

Kiasma museum of contemporary art (1998)

-

Amos Rex art museum (2018)

Theatres[edit]

Helsinki has three major theatres: The Finnish National Theatre, the Helsinki City Theatre, and the Swedish Theatre (Svenska Teatern). Other notable theatres in the city include the Alexander Theatre, Q-teatteri, Savoy Theatre, KOM-theatre, and Teatteri Jurkka.

Music[edit]

Helsinki is home to two full-size symphony orchestras, the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, both of which perform at the Helsinki Music Centre concert hall. Acclaimed contemporary composers Kaija Saariaho, Magnus Lindberg, Esa-Pekka Salonen, and Einojuhani Rautavaara, among others, were born and raised in Helsinki, and studied at the Sibelius Academy. The Finnish National Opera, the only full-time, professional opera company in Finland, is located in Helsinki. The opera singer Martti Wallén, one of the company's long-time soloists, was born and raised in Helsinki, as was mezzo-soprano Monica Groop.

Many widely renowned and acclaimed bands have originated in Helsinki, including Nightwish, Children of Bodom, Hanoi Rocks, HIM, Stratovarius, The 69 Eyes, Finntroll, Ensiferum, Wintersun, The Rasmus, Poets of the Fall, and Apocalyptica. The most significant of the metal music events in Helsinki is the Tuska Open Air Metal Festival in Suvilahti, Sörnäinen.[157]

The city's main musical venues are the Finnish National Opera, the Finlandia concert hall, and the Helsinki Music Centre. The Music Centre also houses a part of the Sibelius Academy. Bigger concerts and events are usually held at one of the city's two big ice hockey arenas: the Helsinki Halli or the Helsinki Ice Hall. Helsinki has Finland's largest fairgrounds, the Messukeskus Helsinki, which is attended by more than a million visitors a year.[158]

Helsinki Arena hosted the Eurovision Song Contest 2007, the first Eurovision Song Contest arranged in Finland, following Lordi's win in 2006.[159]

Art[edit]

Helsinki Day (Helsinki-päivä) will be celebrated every 12 June, with numerous entertainment events culminating in an open-air concert.[160][161] Also, the Helsinki Festival is an arts and culture festival that takes place every August (including the Night of the Arts).[162]

At the Senate Square in fall 2010, Finland's largest open-air art exhibition to date took place: About 1.4 million people saw the international exhibition of United Buddy Bears.[163]

Helsinki was the 2012 World Design Capital, in recognition of the use of design as an effective tool for social, cultural, and economic development in the city. In choosing Helsinki, the World Design Capital selection jury highlighted Helsinki's use of 'Embedded Design', which has tied design in the city to innovation, "creating global brands, such as Nokia, Kone, and Marimekko, popular events, like the annual Helsinki Design Week, outstanding education and research institutions, such as the Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture, and exemplary architects and designers such as Eliel Saarinen and Alvar Aalto".[12]

Helsinki hosts many film festivals. Most of them are small venues, while some have generated interest internationally. The most prolific of these is the Helsinki International Film Festival – Love & Anarchy film festival, also known as Helsinki International Film Festival, which features films on a wide spectrum. Night Visions, on the other hand, focuses on genre cinema, screening horror, fantasy, and science fiction films in very popular movie marathons that last the entire night. Another popular film festival is DocPoint, a festival that focuses solely on documentary cinema.[164][165][166]

Media[edit]

Today,[when?] there are around 200 newspapers, 320 popular magazines, 2,100 professional magazines, 67 commercial radio stations, three digital radio channels, and one nationwide and five national public service radio channels.[citation needed]

Sanoma publishes Finland's journal of record, Helsingin Sanomat, the tabloid Ilta-Sanomat, the commerce-oriented Taloussanomat, and the television channel Nelonen. Another Helsinki-based media house, Alma Media, publishes over thirty magazines, including the tabloid Iltalehti, and the commerce-oriented Kauppalehti.

Finland's national public-broadcasting institution Yle operates five television channels and thirteen radio channels in both national languages. Yle is headquartered in the neighbourhood of Pasila. All TV channels are broadcast digitally, both terrestrially and on cable. Yle's studio area houses the 146-metre (479 ft) high television and radio tower, Yle Transmission Tower (Pasilan linkkitorni),[167] which is the third tallest structure in Helsinki and one of Helsinki's most famous landmarks, from the top of which, in good weather, can be seen even as far as Tallinn over the Gulf of Finland.[168]

The commercial television channel MTV3 and commercial radio channel Radio Nova are owned by Nordic Broadcasting (Bonnier and Proventus).

Food[edit]

Helsinki was already known in the 18th century for its abundant number of inns and pubs, where both locals and those who landed in the harbor were offered plenty of alcoholic beverages.[169] At that time, taxes on the sale of alcohol were a very significant source of income for Helsinki, and one of the most important sellers of alcohol was Johan Sederholm (1722–1805), a trade councilor who attracted rural merchants with alcohol and made good deals.[169] Gradually, a new kind of beverage culture began to grow in the next century, and as early as 1852, the first café of Finland, Café Ekberg,[170][171] was established by confectioner Fredrik Ekberg (1825–1891) after attending his studies in St. Petersburg. Ekberg has also been said to have created Finland's "national pastry tradition".[172] At first, café culture was only a prerogative of sophisticated elite, when it recently began to take shape as the right of every man.[173] Today, there are several hundred cafés in Helsinki, the most notable of which is Cafe Regatta, which is very popular with foreign tourists.[174][175][176]

As an important port city on the Baltic Sea, Helsinki has long been known for its fish food, and it has recently started to become one of the leading fish food capitals in Northern Europe.[177] Helsinki's Market Square is especially known for its traditional herring market, which has been organized since 1743.[178][179][180][181] Salmon is also a typical Helsinki fish dish, both fried and souped.[182] The most prestigious restaurants specializing in seafood include Restaurant Fisken på Disken.[183][184]

Helsinki is currently experiencing a period of booming food culture, and it has developed into an internationally acclaimed food city, receiving recognition for promoting food culture.[181][185][186] The local food culture is made up of cuisines from around the world and the fusions they form. Various Asian restaurants such as Chinese, Thai, Indian and Nepalese are particularly prominent in Helsinki's cityscape, but over the past couple of years, restaurants serving Vietnamese food have been very popular.[177] Sushi restaurant buffets have also made their way into the city's restaurant offerings in one fell swoop.[177] The third prominent trend is restaurants serving pure local food, many of which specialize primarily in serving pure Nordic flavors.[177] In past years Middle Eastern food culture rose in its popularity. Especially Helsinki's eastern part offers many different options for Middle Eastern cuisine lovers.[187] There is also some touches of Russian cuisine, one of which is the Finnish version of blinis, a thick pancakes that are usually fried in a cast-iron pan.[188] One of the most significant food culture venues in Helsinki is the general public area known as Teurastamo in the Hermanni district, which operated as the city's slaughterhouse between 1933 and 1992, to which the name of the place also refers.[181][189][190]

A nationwide food carnival called Restaurant Day (Ravintolapäivä) has begun in Helsinki and has traditionally been celebrated since May 2011.[191] The purpose of the day is to have fun, share new food experiences and enjoy the common environment with the group.[181]

Other[edit]

Vappu is an annual carnival for students and workers on 1 May. The last week of June marks the Helsinki Pride human rights event, which was attended by 100,000 marchers in 2018.[192]

Sports[edit]

Helsinki has a long tradition of sports: the city gained much of its initial international recognition during the 1952 Summer Olympics, and the city has arranged sporting events such as the first World Championships in Athletics 1983 and 2005, and the European Championships in Athletics 1971, 1994, and 2012. Helsinki hosts successful local teams in both of the most popular team sports in Finland: football and ice hockey. Helsinki houses HJK Helsinki, Finland's largest and most successful football club, and IFK Helsingfors, their local rivals with 7 championship titles. The fixtures between the two are commonly known as Stadin derby. Helsinki's track and field club Helsingin Kisa-Veikot is also dominant within Finland. Ice hockey is popular among many Helsinki residents, who usually support either of the local clubs IFK Helsingfors (HIFK) or Jokerit. HIFK, with 14 Finnish championships titles, also plays in the highest bandy division,[193] along with Botnia-69. The Olympic stadium hosted the first Bandy World Championship in 1957.[194]

Helsinki was elected host-city of the 1940 Summer Olympics, but due to World War II they were canceled. Instead Helsinki was the host of the 1952 Summer Olympics. The Olympics were a landmark event symbolically and economically for Helsinki and Finland as a whole that was recovering from the winter war and the continuation war fought with the Soviet Union. Helsinki was also in 1983 the first city to host the World Championships in Athletics. Helsinki also hosted the event in 2005, thus also becoming the first city to host the Championships for a second time. The Helsinki City Marathon has been held in the city every year since 1981, usually in August.[195] A Formula 3000 race through the city streets was held on 25 May 1997. In 2009 Helsinki was host of the European Figure Skating Championships, and in 2017 it hosted World Figure Skating Championships. The city will host the 2021 FIBA Under-19 Basketball World Cup. American football and the Vaahteraliiga has a strong tradition in the city dating back to the early 1980's.

Most of Helsinki's sports venues are under the responsibility of the city's sports office, such as 70 sports halls and about 350 sports fields. There are nine ice rinks, three of which are managed by the Helsinki Sports Agency (Helsingin liikuntavirasto).[196] In winter, there are seven artificial ice rinks. People can swim in Helsinki in 14 swimming pools, the largest of which is the Mäkelänrinne Swimming Centre,[197] two inland swimming pools and more than 20 beaches, of which Hietaniemi Beach is probably the most famous.[198]

Transport[edit]

Roads[edit]

The backbone of Helsinki's motorway network consists of three semicircular beltways, Ring I, Ring II, and Ring III, which connect expressways heading to other parts of Finland, and the western and eastern arteries of Länsiväylä and Itäväylä respectively. While variants of a Keskustatunneli tunnel under the city centre have been repeatedly proposed, as of 2017[update] the plan remains on the drawing board.

Many important Finnish highways leave Helsinki for various parts of Finland; most of them in the form of motorways, but a few of these exceptions include Vihdintie. The most significant highways are:

- Finnish national road 1/E18 (to Lohja, Salo and Turku)

- Finnish national road 3/E12 (to Hämeenlinna, Tampere and Vaasa)

- Finnish national road 4/E75 (to Lahti, Jyväskylä, Oulu and Rovaniemi)

- Finnish national road 7/E18 (to Porvoo and Kotka).

Helsinki has some 390 cars per 1000 inhabitants.[199] This is less than in cities of similar population and construction density, such as Brussels' 483 per 1000, Stockholm's 401, and Oslo's 413.[200][201]

Intercity rail[edit]

Helsinki Central Railway Station is the main terminus of the rail network in Finland. Two rail corridors lead out of Helsinki, the Main Line to the north (to Tampere, Oulu, Rovaniemi), and the Coastal Line to the west (to Turku). The Main Line (päärata), which is the first railway line in Finland, was officially opened on 17 March 1862, between cities of Helsinki and Hämeenlinna.[202] The railway connection to the east branches from the Main Line outside of Helsinki at Kerava, and leads via Lahti to eastern parts of Finland.

A majority of intercity passenger services in Finland originate or terminate at the Helsinki Central Railway Station. All major cities in Finland are connected to Helsinki by rail service, with departures several times a day. The most frequent service is to Tampere, with more than 25 intercity departures per day as of 2017[update].

Until 2022 there also was an international services from Helsinki to Saint Petersburg and Moscow. The Saint Petersburg to Helsinki route was operated by Allegro high-speed trains.

A Helsinki to Tallinn Tunnel has been proposed[203] and agreed upon by representatives of the cities.[204] The rail tunnel would connect Helsinki to the Estonian capital Tallinn, further linking Helsinki to the rest of continental Europe by Rail Baltica.

Aviation[edit]

Air traffic is handled primarily from Helsinki Airport, located approximately 17 kilometres (11 mi) north of Helsinki's downtown area, in the neighbouring city of Vantaa. Helsinki's own airport, Helsinki-Malmi Airport, is mainly used for general and private aviation. Charter flights are available from Hernesaari Heliport.

Sea transport[edit]

Like many other cities, Helsinki was deliberately founded at a location on the sea in order to take advantage of shipping. The freezing of the sea imposed limitations on sea traffic up to the end of the 19th century. But for the last hundred years, the routes leading to Helsinki have been kept open even in winter with the aid of icebreakers, many of them built in the Helsinki Hietalahti shipyard. The arrival and departure of ships has also been a part of everyday life in Helsinki. Regular route traffic from Helsinki to Stockholm, Tallinn, and Saint Petersburg began as far back as 1837. Over 300 cruise ships and 360,000 cruise passengers visit Helsinki annually. There are international cruise ship docks in South Harbour, Katajanokka, West Harbour, and Hernesaari. In terms of combined liner and cruise passengers, the Port of Helsinki overtook the Port of Dover in 2017 to become the busiest passenger port in the world.[205]

Ferry connections to Tallinn, Mariehamn, and Stockholm are serviced by various companies; very popular MS J. L. Runeberg ferry connection to Finland's second oldest city, medieval old town of Porvoo, is also available for tourists.[206] Finnlines passenger-freight ferries to Gdynia, Poland; Travemünde, Germany; and Rostock, Germany are also available. St. Peter Line offers passenger ferry service to Saint Petersburg several times a week.

Urban transport[edit]

In the Helsinki metropolitan area, public transportation is managed by the Helsinki Regional Transport Authority, the metropolitan area transportation authority. The diverse public transport system consists of trams, commuter rail, the metro, bus lines, two ferry lines and a public bike system.

Helsinki's tram system dates back to 1891 when the first horse-drawn trams were introduced; the system was electrified in 1900.[207] As of January 2024[update], the system consists of 14 routes covering the inner part of the city center and one newer light rail style line connecting Keilaniemi in Espoo with Itäkeskus in eastern Helsinki. The length of the network is planned to more than double during the 2020s and 2030s compared to 2021, with major projects including Vantaa light rail, the Crown Bridges link to the island of Laajasalo and the West Helsinki light rail project connecting Kannelmäki to the city center.[208] Construction work on the new tram as the number line 13 (Nihti–Kalasatama–Vallilanlaakso–Pasila) has begun in May 2020, and the line is scheduled for completion in 2024.[209]

The commuter rail system includes purpose-built double track for local services in two rail corridors along intercity railways, and the Ring Rail Line, an urban double-track railway with a station at the Helsinki Airport in Vantaa. Electric operation of commuter trains was first begun in 1969, and the system has been gradually expanded since. 15 different services are operated as of 2017[update], some extending outside of the Helsinki region. The frequent services run at a 10-minute headway in peak traffic.

International relations[edit]

Twin towns and sister cities[edit]

Helsinki has no official sister cities except Beijing, China. On July 14, 2006, Beijing and Helsinki officially became sister cities. In October 2019, the two cities signed the Work Plan for Promoting the Cooperation between Beijing and Helsinki (19-2023).[210][211][212][213] In addition, the city has a special partnership relation with:

Until 2022, Helsinki also had an international partnership with the Russian cities of Moscow and Saint Petersburg, which was suspended after Russian invasion of Ukraine.[214]

Notable people[edit]

Born before 1900[edit]

- Peter Forsskål (1732–1763), Swedish-Finnish naturalist and orientalist

- Axel Hampus Dalström (1829–1882), architect

- Maria Tschetschulin (1850–1917), clerk

- Augusta Krook (1853–1941), politician and teacher

- Agnes Tschetschulin (1859–1942), composer and violinist

- Jakob Sederholm (1863–1934), petrologist

- Karl Fazer (1866–1932), baker, confectioner, chocolatier, entrepreneur, and sport shooter

- Emil Lindh (1867–1937), sailor

- Oskar Merikanto (1868–1924), composer

- Signe Lagerborg-Stenius (1870–1968), architect and member the Helsinki City Council

- Maggie Gripenberg (1881–1976), dancer

- Gunnar Nordström (1881–1923), theoretical physicist

- Väinö Tanner (1881–1966), politician

- Walter Jakobsson (1882–1957), figure-skater

- Mauritz Stiller (1883–1928), Finnish-Swedish director and screenwriter

- Karl Wiik (1883–1946), Social Democratic politician

- Lennart Lindroos (1886–1921), swimmer, Olympic games 1912

- Erkki Karu (1887–1935), film director and producer

- Kai Donner (1888–1935), linguist, anthropologist and politician

- Gustaf Molander (1888–1973), Swedish director and screenwriter

- Johan Helo (1889–1966), lawyer and politician

- Minna Craucher (1891–1932), socialite and spy

- Artturi Ilmari Virtanen (1895–1973), chemist (Nobel Prize, 1945)

- Rolf Nevanlinna (1895–1980), mathematician, university teacher and writer

- Elmer Diktonius (1896–1961), Finnish-Swedish writer and composer

- Yrjö Leino (1897–1961), communist politician

- Toivo Wiherheimo (1898–1970), economist and politician

Born after 1900[edit]

- Aku Ahjolinna (born 1946), ballet dancer and choreographer

- Lars Ahlfors (1907–1996), mathematician, Fields medalist

- Ella Eronen (1900–1987), actress and poetic recite

- Tuomas Holopainen (born 1976), songwriter, multi-instrumentalist and record producer

- Helena Anhava (1925–2018), poet, author and translator

- Paavo Berglund (1929–2012), conductor

- Laci Boldemann (1921–1969), composer

- Irja Agnes Browallius (1901–1968), Swedish writer

- Bo Carpelan (1926–2011), Finland-Swedish writer, literary critic and translator

- Tarja Cronberg (born 1943), politician

- Jörn Donner (1933–2020), writer, film director and politician

- George Gaynes (1917–2016), American television and film actor

- Ragnar Granit (1900–1991), Finnish-Swedish neurophysiologist and Nobel laureate

- Mika Waltari (1908–1979), writer

- Elina Haavio-Mannila (born 1933), social scientist and professor

- Tarja Halonen (born 1943), 11th President of Finland

- Reino Helismaa (1913–1965), writer, film actor and singer

- Kim Hirschovits (born 1982), ice hockey player

- Bengt Holmström (born 1949), Professor of Economics, Nobel laureate

- Shawn Huff (born 1984), basketball player

- Ville Husso (born 1995), ice hockey goaltender

- Kirsti Ilvessalo (1920–2019), textile artist

- Tove Jansson (1914–2001), Finland-Swedish writer, painter, illustrator, comic writer, graphic designer

- Kaapo Kähkönen (born 1996), ice hockey goaltender

- Aki Kaurismäki (born 1957), director, screenwriter and producer

- Emma Kimiläinen (born 1989), racing driver

- Kiti Kokkonen (born 1974), Finnish actress and writer

- Petteri Koponen, basketball player

- Lennart Koskinen (born 1944), Swedish, Lutheran bishop

- Sam Lake (born 1970), writer and actor; the creative director at Remedy Entertainment

- Olli Lehto (1925–2020), mathematician

- Samuel Lehtonen (1921–2010), bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland

- Juha Leiviskä (born 1936), architect

- Magnus Lindberg (born 1958), composer and pianist

- Esa Lindell (born 1994), professional ice hockey player

- Lill Lindfors (born 1940), Finland-Swedish singer and TV presenter

- Jari Mäenpää (born 1977), founder, former lead guitarist and current lead singer in melodic death metal band Wintersun, former lead singer and guitarist of folk metal band Ensiferum

- Klaus Mäkelä (born 1996), cellist and conductor

- Susanna Mälkki (born 1969), conductor

- Georg Malmstén (1902–1981), singer, musician, composer, orchestra director and actor

- Tauno Marttinen (1912–2008), composer

- Vesa-Matti Loiri (1945–2022), actor, comedian, singer

- Abdirahim Hussein Mohamed (born 1978), Finnish-Somalian media personality and politician

- Hanno Möttölä, Finnish basketball player

- Väinö Myllyrinne (1909–1963), acromegalic giant and at time (1940–1963) the world's tallest living person

- Peter Nygård (born 1941), businessman, arrested in December 2020 for sex crimes

- Markku Peltola (1956–2007), actor and musician

- Kimmo Pikkarainen (born 1976), professional ice hockey player

- Anne Marie Pohtamo (born 1955), actress, model, Miss Suomi 1975 and Miss Universe 1975

- Elisabeth Rehn (born 1935), politician

- Einojuhani Rautavaara (1928–2016), composer

- Susanne Ringell (born 1955), writer and actress

- Miron Ruina (born 1998), Finnish-Israeli basketball player

- Kaija Saariaho (1952-2023), composer

- Riitta Salin (born 1950), athlete

- Sasu Salin, Finnish basketball player

- Esa-Pekka Salonen (born 1958), composer and conductor

- Asko Sarkola (born 1945), actor

- Heikki Sarmanto (born 1939), jazz pianist and composer

- Teemu Selänne (born 1970), Hall of Fame ice hockey player

- Ann Selin (born 1960), trade union leader

- Birgit Sergelius (1907–1979), stage and film actress

- Alexander Stubb (born 1968), 13th President of Finland

- Teuvo Teräväinen (born 1994), professional ice hockey player

- Märta Tikkanen (born 1935), Finland-Swedish writer and philosophy teacher

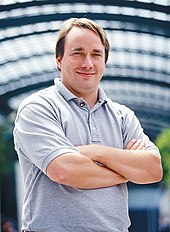

- Linus Torvalds (born 1969), software engineer, creator of Linux

- Elin Törnudd (1924–2008), Finnish chief librarian and professor

- Klaus Törnudd (born 1931), diplomat and political scientist

- Sirkka Turkka (1939–2021), poet

- Jarno Tuunainen (born 1977), footballer

- Ville Valo (born 1976), lead singer of the rock band HIM

- Ulla Vuorela (1945–2011), professor of social anthropology

- Lauri Ylönen (born 1979), lead singer of the rock band The Rasmus

See also[edit]

- Timeline of Helsinki § Bibliography

- Helsinki metropolitan area

- Helsinki urban area

- Subdivisions of Helsinki

- Helsinki Parish Village

- Underground Helsinki

Notes[edit]

- ^ /ˈhɛlsɪŋki/ HEL-sink-ee or /hɛlˈsɪŋki/ hel-SINK-ee "Helsinki". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. "Helsinki". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins.

- ^ Finnish: [ˈhelsiŋki] Swedish: Helsingfors, Finland Swedish: [helsiŋˈforːs]

- ^ Statistics Finland classifies a person as having a "foreign background" if both parents or the only known parent were born abroad.[139]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ainiala, Terhi (2009). "Place Names in the Construction of Social Identities: The Uses of Names of Helsinki". Research Institute for the Languages of Finland. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b [1] [permanent dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Helsinki, Pearl of the Baltic Sea". Myhelsinki.fi. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ "Area of Finnish Municipalities 1.1.2018" (PDF). National Land Survey of Finland. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ "Helsinki elevation". elevation.city.fi. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ "Population growth biggest in nearly 70 years". Population structure. Statistics Finland. 26 April 2024. ISSN 1797-5395. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "Population growth biggest in nearly 70 years". Population structure. Statistics Finland. 26 April 2024. ISSN 1797-5395. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "Population according to age (1-year) and sex by area and the regional division of each statistical reference year, 2003–2020". StatFin. Statistics Finland. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Luettelo kuntien ja seurakuntien tuloveroprosenteista vuonna 2023". Tax Administration of Finland. 14 November 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ "Cities of Finland". Eurostat. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Sipoo - kahden keskuksen kunta Helsingin tuntumassa". ta.fi. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Past capital: Helsinki". Worlddesigncapital.com. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Most liveable city: Helsinki — Monocle Film / Affairs". Monocle.com. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Global Liveability Ranking 2016". www.eiu.com.

- ^ "Helsinki: The World's 100 Greatest Places of 2021". Time.com. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ "Helsinki comes in third in ranking of world's best cities to live". Helsinki Times. 14 July 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ Ghouri, Farah (4 August 2021). "London hailed as world's 'city of choice' in quality of life report". City A.M. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "The friendliest cities in Europe: 2023 Readers' Choice Awards". Condé Nast Traveler. 3 October 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ Lapin Kansa: Rovaniemen ja Helsingin johtajat saivat ministeriltä tehtävän miettiä, miten matkailu nousee korona-ajan mentyä ohi – Rahaa on luvassa EU:n elpymispaketista (in Finnish)

- ^ Roberts, Toby; Williams, Ian; Preston, John (2021). "The Southampton system: A new universal standard approach for port-city classification". Maritime Policy & Management. 48 (4): 530–542. doi:10.1080/03088839.2020.1802785. S2CID 225502755.

- ^ "Helsinki becomes world's busiest passenger port". clickittefaq. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Salminen, Tapio (2013). Vantaan ja Helsingin pitäjän keskiaika [The Middle-age in Vantaa and Helsinki] (in Finnish). Vantaa: Vantaan kaupunki. ISBN 978-952-443-455-3.

- ^ Hellman, Sonja (7 June 2015). "Historiska fel upprättas i ny bok" [Historical misinformation corrected in new book]. Hufvudstadsbladet (in Swedish).

- ^ "Utbildning & Vetenskap: Svenskfinland". Veta.yle.fi. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ "Onko kosken alkuperäinen nimi Helsinginkoski vai Vanhankaupunginkoski?". Helsinginkoski. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ Jäppinen, Jere (2007). "Helsingin nimi" (PDF). www.helsinginkaupunginmuseo.fi. Helsingin kaupunginmuseo. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ Jäppinen, Jere (15 November 2011). "Mistä Helsingin nimi on peräisin?". Helsingin Sanomat: D2. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ Ristkari, Maiju: Heinäsorsat Helsingissä. Aku Ankka #44/2013, introduction on page 2.

- ^ "Sami Grammar". uta.fi. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kent, Neil (2004). Helsinki: A cultural and literary history. Oxford: Signal Books.

- ^ Jump up to: a b V.-P. Suhonen and Janne Heinonen. "Helsingin keskiaikaiset ja uuden ajan alun kylänpaikat 2011, Inventointiraportti. Museovirasto, Arkeologiset kenttäpalvelut" (PDF).

- ^ "Keskiaikainen Helsingin pitäjä | Historia Helsinki". historia.hel.fi (in Finnish). 4 March 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Väätäinen, Erika (4 March 2022). "Were There Ever Vikings In Finland Or Finnish Vikings?". Scandification. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ "The Battle of Herdaler".

Saga of Olaf Haraldson. See chapter 8: The Third Battle.

- ^ Talvio, Tuukka (2002). Suomen museo 2002. Vammala: Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys. ISBN 951-9057-47-1.

- ^ Tarkiainen, Kari (2010). Ruotsin itämaa. Helsinki: Svenska litteratussällskapet i Finland. pp. 122–125.

- ^ "Keskiaikainen Helsingin pitäjä | Historia Helsinki". historia.hel.fi (in Finnish). 4 March 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ "Keskiaikaista arkea Helsingin pitäjässä | Historia Helsinki". historia.hel.fi (in Finnish). 16 November 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ruttopuisto – Plague Park". Tabblo.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Helsingin historia". Helsingin kaupunki (in Finnish).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Helsinki – Suomi". Matkaoppaat.com (in Finnish). Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ "Suuri Pohjan sota ja Helsingin tuho" (in Finnish). City of Helsinki. 21 January 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Aalto, Seppo (2015). Kruununkaupunki – Vironniemen Helsinki 1640–1721 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. ISBN 978-952-222-675-4.

- ^ Niukkanen, Marianna; Heikkinen, Markku. "Vuoden 1808 suurpalo". Kurkistuksia Helsingin kujille (in Finnish). National Board of Antiquities. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "8 April 1812 Emperor Alexander I promotes Helsinki to the capital of the Grand Duchy. - Helsinki 200 years as capital". Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Bicentennial of Helsinki as Finnish capital". Yle News. 8 April 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ "Lobbying for Helsinki 200 years ago". Helsinki Times. 19 April 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Marjo Vilkko (2014). "Stadin slangi". Suomi on ruotsalainen (in Finnish). Helsinki: Schildts & Söderströms. pp. 216–219. ISBN 978-951-52-3419-3.

- ^ "The White Pearl of the Baltic Sea – Helsinki Deals with Snow". Hooniverse.com. 3 January 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Kotka, Tiina (14 May 2020). "Stadilla on 60 luonnonsuojelualuetta" (PDF). Helsinki-lehti (in Finnish). No. 2/2020. City of Helsinki. p. 27. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "Mitkä ovat Helsingin nimikkoeläin ja nimikkokasvi?". Kysy kirjastonhoitajalta (in Finnish). Helsinki City Library. 30 August 2001. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "Aluejaot". Tietopalvelu (in Finnish). Uudenmaan liitto. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "Uudenmaan maakuntakaava selostus" (PDF) (in Finnish). Helsinki-Uusimaa Region. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ "Pääkaupunkiseutu, Suur-Helsinki ja Helsingin seutu". Kotus (in Finnish). Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "Helsingin seutu tiivistetysti". Kaupunkitieto (in Finnish). Helsinginseutu.fi. 19 December 2022.

- ^ "Climate Helsinki: Temperature, Climograph, Climate table for Helsinki - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ "Climatological statistics for the normal period 1971–2000". Fmi.fi. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ Tukiainen, Matti. "Helsinki, Finland – Sunrise, sunset, dawn and dusk times around the World!". Gaisma. Retrieved 11 February 2011.