Timeline of the name Palestine

This article presents a list of notable historical references to the name Palestine as a place name for the region of Palestine throughout history. This includes uses of the localized inflections in various languages, such as Arabic Filasṭīn and Latin Palaestina.

A possible predecessor term, Peleset, is found in five inscriptions referring to a neighboring people, starting from c. 1150 BCE during the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt. The word was transliterated from hieroglyphs as P-r-s-t.

The first known mention of Peleset is at the Medinet Habu temple, which refers to the Peleset among those who fought against Egypt during Ramesses III's reign,[2] and the last known is 300 years later on Padiiset's Statue. The Assyrians called the same region "Palashtu/Palastu" or "Pilistu," beginning with Adad-nirari III in the Nimrud Slab in c. 800 BCE through to an Esarhaddon treaty more than a century later.[3][4] Neither the Egyptian nor the Assyrian sources provided clear regional boundaries for the term.[5] Whilst these inscriptions are often identified with the Biblical Pəlīštīm, i.e. Philistines,[6] the word means different things in different parts of the Bible.[7][8] The 10 uses in the Torah have undefined boundaries and no meaningful description, and the usage in two later books describing coastal cities in conflict with the Israelites – where the Septuagint instead uses the term "allophuloi" (Αλλόφυλοι, "other nations") – has been interpreted to mean "non-Israelites of the Promised Land".[9][10]

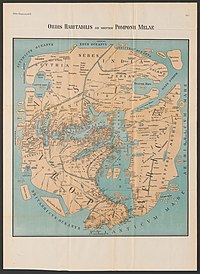

The term Palestine first appeared in the 5th century BCE when the ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote of a "district of Syria, called Palaistinê" between Phoenicia and Egypt in The Histories.[11] Herodotus provides the first historical reference clearly denoting a wider region than biblical Philistia, as he applied the term to both the coastal and the inland regions such as the Judean Mountains and the Jordan Rift Valley.[12][13][14][15] Later Greek writers such as Aristotle, Polemon and Pausanias also used the word, which was followed by Roman writers such as Ovid, Tibullus, Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, Dio Chrysostom, Statius, Plutarch as well as Roman Judean writers Philo of Alexandria and Josephus.[16] There is no evidence of the name on any Hellenistic coin or inscription.[17]

In the early 2nd century CE, the Roman province called Judaea was renamed Syria Palaestina[a] (literally, "Palestinian Syria"), and also incorporated some other, smaller, territories.[18][19] This may have occurred either before or after the suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135.[20][21][22][23]

Around the year 390, during the Byzantine period, the imperial province of Syria Palaestina was reorganized into Palaestina Prima, Palaestina Secunda[24] and Palaestina Salutaris.[24] Following the Muslim conquest, place names that were in use by the Byzantine administration generally continued to be used in Arabic,[3][25] and the Jund Filastin became one of the military districts within the Umayyad and Abbasid province of Bilad al-Sham.[26]

The use of the name "Palestine" became common in Early Modern English,[27] was used in English and Arabic during the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem. The term was used widely as a self-identification by Palestinians from the start of the 20th century onwards.[28] In the 20th century the name was used by the British to refer to "Mandatory Palestine," a territory from the former Ottoman Empire which had been divided in the Sykes–Picot Agreement and secured by Britain via the Mandate for Palestine obtained from the League of Nations.[29] Starting from 2013, the term was officially used in the eponymous "State of Palestine."[30] Both incorporated geographic regions from the land commonly known as Palestine, into a new state whose territory was named Palestine.

Etymological considerations

The English term "Palestine" itself is borrowed from Latin Palaestīna,[31] which is, in turn, borrowed from Ancient Greek Παλαιστῑ́νη, Palaistī́nē, used by Herodotus in the 5th century BCE.[11][32] Per Martin Noth, while the term in Greek likely originated from an Aramaic loanword, its Greek form showed clear derivation from παλαιστής, palaistês, the Greek noun meaning "wrestler/rival/adversary".[33] David Jacobson noted the significance of wrestlers in Greek culture, and further speculated that Palaistinê was meant as both a transliteration of the Greek word for "Philistia" and a direct translation of the Hebrew name "Israel" — as the traditional etymology of which also relates to wrestling, and in line with the Greek penchant for punning transliterations of foreign place names.[34][35]

Whilst the term was used in Egyptian and Assyrian times, prior to the time period in which the Bible is thought to have been written, scholars generally conclude that the term is cognate with the Biblical Hebrew פְּלִשְׁתִּים Pəlīštīm.[36][37][38] The further etymology is uncertain; it is unknown whether the term was an endonym or exonym, no word for Philistia has been found in the sparse attestations of the Philistine language, and it is unknown whether the Hebrew, Egyptian, and Assyrian terms derived from a common source, or if they simply borrowed the name from one another and changed it to match their own phonological customs.

In English versions of the Bible, Pəlīštīm is translated as "Philistines"; however, it is thought that the word means different things in different parts of the Bible. The word and its derivates are used more than 250 times in Masoretic-derived versions of the Hebrew Bible,[39][40] of which 10 uses are in the Torah (the first use being in Genesis 10, in the Generations of Noah),[41] with undefined boundaries and no meaningful description, and almost 200 of the remaining references are in the later Book of Judges and the Books of Samuel that contain the well known biblical story of a coastal state in conflict with the Israelites.[3][16][42]

By the time the Septuagint (LXX) was translated, the term Palaistínē (Παλαιστίνη), first popularized in written form by Herodotus, had already entered the Greek vocabulary. However, the term was not used in the LXX to describe Philistia. Instead, the term Land of the Phylistieim (Γη των Φυλιστιειμ) is used from the books of Genesis through Joshua.[8][43] The Septuagint later uses the alternate term "allophiloi" (Αλλόφυλοι, "other nations") from the Books of Judges onward,[7][9] such that post-Judges invocation of "Philistines" in Septuagint-based translations have been interpreted to mean "non-Israelites of the Promised Land" when used in the context of Samson, Saul and David.[10] Rabbinic sources explain that these peoples were different from the Philistines of the Book of Genesis.[7]

Historical references

Ancient period

Egyptian period

- c. 1150 BCE: Medinet Habu: records a people called the P-r-s-t (conventionally Peleset) among those who fought against Egypt in Ramesses III's reign.[2][6]

- c. 1150 BCE: Papyrus Harris I: "I extended all the boundaries of Egypt; I overthrew those who invaded them from their lands. I slew the Denyen in their isles, the Thekel and the Peleset (Pw-r-s-ty) were made ashes."[44][45]

- c. 1150 BCE: Rhetorical Stela to Ramesses III, Chapel C, Deir el-Medina.[46]

- c. 1000 BCE: Onomasticon of Amenope: "Sherden, Tjekker, Peleset, Khurma."[47][45]

- c. 900 BCE: Padiiset's Statue, inscription: "envoy – Canaan – Peleset."[48]

Assyrian period

- c. 800 BCE: Adad-nirari III, Nimrud Slab.[49]

- c. 800 BCE: Adad-nirari III, Saba'a Stele: "In the fifth year (of my official rule) I sat down solemnly on my royal throne and called up the country (for war). I ordered the numerous army of Assyria to march against Philistia (Pa-la-áš-tu)... I received all the tributes [...] which they brought to Assyria. I (then) ordered [to march] against the country Damascus (Ša-imērišu)."[50]

- c. 735 BCE: Qurdi-Ashur-lamur to Tiglath-Pileser III, Nimrud Letter ND 2715: "Bring down lumber, do your work on it, (but) do not deliver it to the Egyptians (mu-sur-a-a) or Philistines (pa-la-as-ta-a-a), or I shall not let you go up to the mountains."[51][52]

- c. 717 BCE: Sargon II's Prism A: records the region as Palashtu or Pilistu.[53]

- c. 700 BCE: Azekah Inscription[54] records the region as Pi-lis-ta-a-a.[55]

- c. 694 BCE: Sennacherib "Palace Without a Rival: A Very Full Record of Improvements in and about the Capital (E1)": (the people of) Kue and Hilakku, Pilisti and Surri ("Ku-e u Hi-lak-ku Pi-lis-tu u Sur-ri").[56]

- c. 675 BCE: Esarhaddon's Treaty with Ba'al of Tyre: Refers to the entire district of Pilistu (KURpi-lis-te).[57]

Classical antiquity

Persian (Achaemenid) Empire period

- c. 450 BCE: Herodotus, The Histories[58], First historical reference clearly denoting a wider region than biblical Philistia, referring to a "district of Syria, called Palaistinê"[59][15][60] (Book 3[61]): "The country reaching from the city of Posideium to the borders of Egypt... paid a tribute of three hundred and fifty talents. All Phoenicia, Palestine Syria, and Cyprus, were herein contained. This was the fifth satrapy.";[b] (Book 4): "the region I am describing skirts our sea, stretching from Phoenicia along the coast of Palestine-Syria till it comes to Egypt, where it terminates"; (Book 7[62]): "[The Phoenicians and the Syrians of Palestine], according to their own account, dwelt anciently upon the Erythraean Sea, but crossing thence, fixed themselves on the seacoast of Syria, where they still inhabit. This part of Syria, and all the region extending from hence to Egypt, is known by the name of Palestine." One important reference refers to the practice of male circumcision associated with the Hebrew people: "the Colchians, the Egyptians, and the Ethiopians, are the only nations who have practised circumcision from the earliest times. The Phoenicians and the Syrians of Palestine themselves confess that they learnt the custom of the Egyptians.... Now these are the only nations who use circumcision."[63][64]

- c. 340 BCE: Aristotle, Meteorology, "Again if, as is fabled, there is a lake in Palestine, such that if you bind a man or beast and throw it in it floats and does not sink, this would bear out what we have said. They say that this lake is so bitter and salt that no fish live in it and that if you soak clothes in it and shake them it cleans them." This is understood by scholars to be a reference to the Dead Sea.[65]

Hellenic kingdoms (Ptolemaic/Seleucid/Hasmonean) period

- c. 150 BCE: Polemon of Athens, Greek Histories, quoted by Eusebius of Caesarea in Praeparatio Evangelica: "In the time [reign] of Apis son of Phoroneus a part of the Egyptian army was expelled from Egypt, who took up their abode not far from Arabia in the part of Syria called Palestine."[66][67][68]

- c. 130 BCE: Agatharchides (5.87, quoted in Diodorus Siculus's Bibliotheca historica; Strabo's Geographica, and Photios' Bibliotheca): "Near (Tiran) island is a promontory, which stretches towards the Rock of the Nabataeans and Palestine."[69][70][71][72][73][74]

Roman Jerusalem period

Writers during this period also used the term Palestine to refer to the entire region between Syria and Egypt, with numerous references to the Jewish areas within Palestine.[75][76] It has been contended that some first century authors associated the term with the southern coastal region.[77][78]

- c. 30 BCE: Tibullus, Tibullus and Sulpicia: The Poems: "Why tell how the white dove sacred to the Syrians flies unharmed through the crowded cities of Palestine?"[79][80]

- c. 2 CE: Ovid, Ars Amatoria: "the seventh-day feast that the Syrian of Palestine observes."[81][82]

- c. 8 CE: Ovid, Metamorphoses: (1) "...Dercetis of Babylon, who, as the Palestinians believe, changed to a fish, all covered with scales, and swims in a pool"[83] and (2) "There fell also Mendesian Celadon; Astreus, too, whose mother was a Palestinian, and his father unknown."[84][82]

- c. 17 CE: Ovid, Fasti (poem): "When Jupiter took up arms to defend the heavens, came to Euphrates with the little Cupid, and sat by the brink of the waters of Palestine."[85][82]

- c. 40 CE: Philo of Alexandria, (1) Every Good Man is Free: "Moreover Palestine and Syria too are not barren of exemplary wisdom and virtue, which countries no slight portion of that most populous nation of the Jews inhabits. There is a portion of those people called Essenes.";[86] (2) On the Life of Moses: "[Moses] conducted his people as a colony into Phoenicia, and into the Coele-Syria, and Palestine, which was at that time called the land of the Canaanites, the borders of which country were three days' journey distant from Egypt.";[87][88] (3) On Abraham: "The country of the Sodomites was a district of the land of Canaan, which the Syrians afterwards called Palestine."[89][90]

- c. 43 CE: Pomponius Mela, De situ orbis (Description of the World): "Syria holds a broad expanse of the littoral, as well as lands that extend rather broadly into the interior, and it is designated by different names in different places. For example, it is called Coele, Mesopotamia, Judaea, Commagene, and Sophene. It is Palestine at the point where Syria abuts the Arabs, then Phoenicia, and then—where it reaches Cilicia—Antiochia. [...] In Palestine, however, is Gaza, a mighty and well fortified city."[91][92][90]

- c. 78: Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Volume 1, Book V: Chapter 13: "Next to these countries Syria occupies the coast, once the greatest of lands, and distinguished by many names; for the part which joins up to Arabia was formerly called Palaestina, Judaea, Coele,[c] and Phoenice. The country in the interior was called Damascena, and that further on and more to the south, Babylonia."; Chapter 14: "After this, at the point where the Serbonian Bog becomes visible, Idumea and Palaestina begin. This lake, which some writers have made to be 150 miles in circumference, Herodotus has placed at the foot of Mount Casius; it is now an inconsiderable fen. The towns are Rhinocorura and, in the interior, Rafah, Gaza, and, still more inland, Anthedon: there is also Mount Argaris";[93] Book XII, Chapter 40: "For these branches of commerce, they have opened the city of Carræ, which serves as an entrepot, and from which place they were formerly in the habit of proceeding to Gabba, at a distance of twenty days' journey, and thence to Palæstina, in Syria."[94][90]

- c. 80: Marcus Valerius Probus, Commentary on Georgics: "Edomite palms from Idumea, that is Judea, which is in the region of Syria Palestine."[95]

- c. 85: Silius Italicus, Punica: "While yet a youth, he [Titus] shall put an end to war with the fierce people of Palestine."[96][97]

- c. 90: Dio Chrysostom, quoted by Synesius, refers to the Dead Sea as being in the interior of Palestine, in the very vicinity of "Sodoma."[98]

- c. 94: Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews: "...these Antiquities contain what hath been delivered down to us from the original creation of man, until the twelfth year of the reign of Nero, as to what hath befallen us Jews, as well is Egypt as in Syria, and in Palestine."[99][90]

- c. 94: Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews: "...the children of Mesraim, being eight in number, possessed the country from Gaza to Egypt, though it retained the name of one only, the Philistim; for the Greeks call part of that country Palestine."[100]

- c. 94: Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews: "... Aram had the Aramites, which the Greeks called Syrians; as Laud founded the Laudites, which are now called Lydians. Of the four sons of Aram, Uz founded Trachonitis and Damascus: this country lies between Palestine and Coelesyria."[101]

- c. 97: Josephus, Against Apion: "Nor, indeed, was Herodotus of Halicarnassus unacquainted with our nation, but mentions it after a way of his own... This, therefore, is what Herodotus says, that "the Syrians that are in Palestine are circumcised." But there are no inhabitants of Palestine that are circumcised excepting the Jews; and, therefore, it must be his knowledge of them that enabled him to speak so much concerning them."[102][90]

- c. 100: Statius, Silvae, refers to "liquores Palestini"[103][82] and "Isis, ...gently with thine own hand lead the peerless youth, on whom the Latian prince hath bestowed the standards of the East and the bridling of the cohorts of Palestine, (i.e., a command on the Syrian front) through festal gate and sacred haven and the cities of thy land."[104][105]

- c. 100: Plutarch, Parallel Lives: "Armenia, where Tigranes reigns, king of kings, and holds in his hands a power that has enabled him to keep the Parthians in narrow bounds, to remove Greek cities bodily into Media, to conquer Syria and Palestine, to put to death the kings of the royal line of Seleucus, and carry away their wives and daughters by violence."[106] and "The triumph [of Pompey] was so great, that though it was divided into two days, the time was far from being sufficient for displaying what was prepared to be carried in procession; there remained still enough to adorn another triumph. At the head of the show appeared the titles of the conquered nations; Pontus Armenia, Cappadocia, Paphlagonia, Media, Colchis, the Iberians, the Albanians, Syria, Cilicia, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Palestine, Judea, Arabia, the pirates subdued both by sea and land."[107]

- c. 100: Achilles Tatius, Leucippe and Cleitophon and other love stories in eight books: "Your father did not return from his absence in Palestine until two days later; and he then found a letter had arrived from Leucippe's father—it had come the very day after our flight—betrothing his daughter to you."[108]

Roman Aelia Capitolina period

- c. 129 or 135: Syria Palæstina[a] was a Roman province between 135 and about 390.[109] It was established by the merger of Roman Syria and Roman Judaea, shortly before or after the Bar Kokhba Revolt. There is only circumstantial evidence linking Hadrian with the name change and the precise date is not certain.[31] The common view that the name change was intended to "sever the connection of the Jews to their historical homeland" is disputed.[110] Zachary Foster in his doctoral dissertation wrote that "Most scholars believe the Roman Emperor Hadrian changed the provincial administrative name of Judaea to Palestine to erase the Jewish presence in the land," opining that "it’s equally likely the name change had little to do with Jew hatred and more to do with Hadrian’s romance with ancient Greece." He adds, there is a "paucity of direct evidence around who made the change, when and under what circumstances", and that it may be that Hadrian did not "rename" the country but simply "called the place what it was called".[111] Louis Feldman argues prior to change of province name the term was used to refer to the coastal region associated with the Philistines and that first century authors differentiated Judea from Palestine.[112]

- 139: A Roman military diploma from Afiq names military units "in Syria Palaestin[a]."[113][114][115][116]

- c. 130: Pausanias (geographer),[117] Description of Greece: (1) "Hard by is a sanctuary of the Heavenly Aphrodite; the first men to establish her cult were the Assyrians, after the Assyrians the Paphians of Cyprus and the Phoenicians who live at Ascalon in Palestine; the Phoenicians taught her worship to the people of Cythera.";[118] (2) "In front of the sanctuary grow palm-trees, the fruit of which, though not wholly edible like the dates of Palestine, yet are riper than those of Ionia.";[119] and (3) "[a Hebrew Sibyl] brought up in Palestine named Sabbe, whose father was Berosus and her mother Erymanthe. Some say she was a Babylonian, while others call her an Egyptian Sibyl."[120]

- c. 150: Aelius Aristides, To Plato: In Defense of the Four: (671) These men alone should be classed neither among flatterers nor free men. For they deceive like flatterers, but they are insolent as if they were of higher rank, since they are involved in the two most extreme and opposite evils, baseness and willfulness, behaving like those impious men of Palestine. For the proof of the impiety of those people is that they do not believe in the higher powers. And these men in a certain fashion have defected from the Greek race, or rather from all that is higher.[121]

- c. 150: Appian, Roman History: "Intending to write the history of the Romans, I have deemed it necessary to begin with the boundaries of the nations under their sway.... Here turning our course and passing round, we take in Palestine-Syria, and beyond it a part of Arabia. The Phoenicians hold the country next to Palestine on the sea, and beyond the Phoenician territory are Coele-Syria, and the parts stretching from the sea as far inland as the river Euphrates, namely Palmyra and the sandy country round about, extending even to the Euphrates itself."[122]

- c. 150: Lucian of Samosata, Passing of Peregrinus: 11. "It was then that he learned the wondrous lore of the Christians, by associating with their priests and scribes in Palestine. And—how else could it be?—in a trice he made them all look like children, for he was prophet, cult-leader, head of the synagogue, and everything, all by himself. He interpreted and explained some of their books and even composed many, and they revered him as a god, made use of him as a lawgiver, and set him down as a protector, next after that other, to be sure, whom they still worship, the man who was crucified in Palestine because he introduced this new cult into the world.[123][124]

- c. 150: Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri:[b] "Tyre then was captured, in the archonship at Athens of Anicetus in the month I lecatombacun...Alexander now determined to make his expedition to Egypt. The rest of Syrian Palestine (as it is called) had already come over to him, but a certain eunuch, Batis, who was master of Gaza, did not join Alexander."[125]

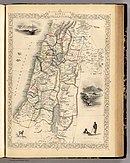

- c. 150: Ptolemy, Geography (Ptolemy), including map.[126]

- 155: First Apology of Justin Martyr, refers to "Flavia Neapolis in Palestine" in the introductory paragraph.

- 159: Coins from the Neapolis mint from the time of Antoninus Pius: Flavia Neapolis (?), in Syria, in Palestine, year 88 (in Greek).[127]

- c. 200: Ulpian, On Taxes: Book I. It should be remembered that there are certain coloniae subject to the Italian Law. ...The colony of Ptolemais, which is situated between Phoenicia and Palestine, has nothing but the name of a colony. ...In Palestine there are two colonies, those of Caesarea and Aelia Capitolina; but neither of these enjoy Italian privileges.[128]

- c. 200: Tertullian, The Works of Tertullian: Palestine had not yet received from Egypt its Jewish swarm (of emigrants), nor had the race from which Christians sprung yet settled down there, when its neighbors Sodom and Gomorrah were consumed by fire from heaven.[129]

- c. 200: Sextus Julius Africanus, Epistle to Aristides: Some Idumean robbers attacking Ascalon, a city of Palestine, besides other spoils which they took from a temple of Apollo, which was built near the walls, carried off captive one Antipater, son of a certain Herod, a servant of the temple. And as the priest was not able to pay the ransom for his son, Antipater was brought up in the customs of the Idumeans, and afterwards enjoyed the friendship of Hyrcanus, the high priest of Judea. And being sent on an embassy to Pompey on behalf of Hyrcanus, and having restored to him the kingdom which was being wasted by Aristobulus his brother, he was so fortunate as to obtain the title of procurator of Palestine.[130]

- c. 225: Cassius Dio, Historia Romana: The Eastern Wars c. 70 BCE —"This was the course of events at that time in Palestine; for this is the name that has been given from of old to the whole country extending from Phoenicia to Egypt along the inner sea. They have also another name that they have acquired: the country has been named Judaea, and the people themselves Jews."[131] [...] The Destruction of Jerusalem by Titus in 70 CE —"Such was the course of these events; and following them Vespasian was declared emperor by the senate also, and Titus and Domitian were given the title of Caesars. The consular office was assumed by Vespasian and Titus while the former was in Egypt and the latter in Palestine."[132]

- c. 300: Flavius Vopiscus, Augustan History:[133][134] On the lives of Firmus, Saturninus, Proculus and Bonosus: "So then, holding such an opinion about the Egyptians Aurelian forbade Saturninus to visit Egypt, showing a wisdom that was truly divine. For as soon as the Egyptians saw that one of high rank had arrived among them, they straightway shouted aloud, "Saturninus Augustus, may the gods keep you!" But he, like a prudent man, as one cannot deny, fled at once from the city of Alexandria and returned to Palestine."[135] On the Life of Septimius Severus: "And not long afterwards he [Severus] met with Niger near Cyzicus, slew him, and paraded his head on a pike. ...The citizens of Neapolis in Palestine, because they had long been in arms on Niger's side, he deprived of all their civic rights, and to many individuals, other than members of the senatorial order, who had followed Niger he meted out cruel punishments."[136] On the life of Aurelian: "Aurelian, now ruler over the entire world, having subdued both the East and the Gauls, and victor in all lands, turned his march toward Rome, that he might present to the gaze of the Romans a triumph. ...There were three royal chariots, ...twenty elephants, and two hundred tamed beasts of diverse kinds from Libya and Palestine."[137]

- c. 300: Antonine Itinerary.[138][139]

- 311: Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea, History of the Martyrs in Palestine. As the "Father of Church History," Eusebius' use of the name Palestine influenced later generations of Christian writers.[140][141]

Late Antiquity period

Late Roman Empire (Byzantine) period

- c. 362: Julian, Against the Galileans: "Why were you so ungrateful to our gods as to desert them for the Jews?" Was it because the gods granted the sovereign power to Rome, permitting the Jews to be free for a short time only, and then forever to be enslaved and aliens? Look at Abraham: was he not an alien in a strange land? And Jacob: was he not a slave, first in Syria, then after that in Palestine, and in his old age in Egypt? Does not Moses say that he led them forth from the house of bondage out of Egypt "with a stretched out arm"?[144] And after their sojourn in Palestine did they not change their fortunes more frequently than observers say the chameleon changes its colour, now subject to the judges,[145] now enslaved to foreign races?[146]

- c. 365: Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribus: Vespasian ruled ten years. [...] Volgeses, King of Parthia, was compelled to peace. The Syria for which Palestina is the name, and Cilicia, and Trachia and Commagene, which today we call Augustophratensis, were added to the provinces. Judaea, too, was added.[147]

- c. 370: Eutropius, Breviarium historiae Romanae: "Vespasian, who had been chosen emperor in Palestine, a prince indeed of obscure birth, but worthy to be compared with the best emperors."[148] and "Under him Judæa was added to the Roman Empire; and Jerusalem, which was a very famous city of Palestine."[149]

- c. 380: Ammianus Marcellinus, "Book XIV," The Roman History of Ammianus Marcellinus: Book XIV, 8, 11. "The last province of the Syrias is Palestine, a district of great extent, abounding in well-cultivated and beautiful land, and having several magnificent cities, all of equal importance, and rivalling one another as it were, in parallel lines. For instance, Caesarea, which Herod built in honour of the Prince Octavianus, and Eleutheropolis, and Neapolis, and also Ascalon, and Gaza, cities built in bygone ages."[150][143][151]

- c. 384: Saint Jerome, Epistle 33: "He (Origen) stands condemned by his bishop, Demetrius, only the bishops of Palestine, Arabia, Phenicia, and Achaia dissenting."[103][152][82]

- c. 385: Egeria, Itinerary: "The greatest part of Palestine, the land of promise, was in sight, together with the whole land of Jordan, as far as it could be seen with our eyes."[153]

- 390: Auxentius of Durostorum (else Maximinus the Arian), Commenttarium on Iob:[154][155][156] "In regione Arabiae et Palaestinorum asini, qui veloces sunt similiter ut equi."[157]

- c. 390: John Chrysostom, On Wealth and Poverty: ""What about Abraham?" someone says. Who has suffered as many misfortunes as he? Was he not exiled from his country? Was he not separated from all his household? Did he not endure hunger in a foreign land? Did he not, like a wanderer, move continually, from Babylon to Mesopotamia, from there to Palestine, and from there to Egypt?"[158] and Adversus Judaeos: "VI...[7] Do you not see that their Passover is the type, while our Pasch is the truth? Look at the tremendous difference between them. The Passover prevented bodily death: whereas the Pasch quelled God's anger against the whole world; the Passover of old freed the Jews from Egypt, while the Pasch has set us free from idolatry; the Passover drowned the Pharaoh, but the Pasch drowned the devil; after the Passover came Palestine, but after the Pasch will come heaven."[159][160]

- c. 390: Palaestina was organised into three administrative units: Palaestina Prima, Secunda, and Tertia (First, Second, and Third Palestine), part of the Diocese of the East.[161][162] Palaestina Prima consisted of Judea, Samaria, the Paralia, and Peraea with the governor residing in Caesarea. Palaestina Secunda consisted of the Galilee, the lower Jezreel Valley, the regions east of Galilee, and the western part of the former Decapolis with the seat of government at Scythopolis. Palaestina Tertia included the Negev, southern Jordan—once part of Arabia—and most of Sinai with Petra as the usual residence of the governor. Palestina Tertia was also known as Palaestina Salutaris.[163] Recorded in the:

- Codex Theodosianus, published in 438, and containing previous laws, including a first mention in 409.[164]

- Synecdemus of Hierocles (c. 530)[165]

- Descriptio Orbis Romani of George of Cyprus (c. 600)[166]

- 392: Epiphanius of Salamis, On Weights and Measures: "So [Hadrian] passed through the city of Antioch and passed through [Coele-Syria] and Phoenicia and came to Palestine — which is also called Judea — forty-seven years after the destruction of Jerusalem."[167]

- c. 400: Genesis Rabba (90.6), Jewish midrash, proposes that the word "land" in Genesis 41:54 refers to three lands in the region – Phoenicia, Arabia and Palestine.(ויהי רעב בכל הארצות: בשלש ארצות בפנקיא ובערביא ובפלסטיני)[82]

- c. 400: Lamentations Rabbah (1.5), Jewish midrash, proposes that the dukes of Arabia, Africa, Alexandria, and Palestine, had joined forces with Roman Emperor Vespasian. (שלש שנים ומחצה הקיף אספסיאנוס את ירושלם והיו עמו ארבעה דוכסין, דוכס דערביא, דוכס דאפריקא, דוכוס דאלכסנדריא, דוכוס דפלסטיני)[82]

- c. 400: Leviticus Rabbah (parasha 5, verse 3) proposes Gath of the Philistines is the same as the "(hills or forts) of Palestine" (תלוליא דפלסטיני).

- c. 400: Cursus publicus, Tabula Peutingeriana: map: Roman road network, map index.

- c. 411: Jerome, Hieronymus on Ezekiel:[168] "iuda et terra Israel ipsi institores tui in frumento primo; balsamum et mel et oleum et resinam proposuerunt in nundinis tuis. (lxx: iudas et filii Israel isti negotiatores tui in frumenti commercio et unguentis; primum mel et oleum et resinam dederunt in nundinis tuis). uerbum hebraicum 'phanag' aquila, symmachus et theodotio ita ut apud hebraeos positum est transtulerunt, pro quo septuaginta 'unguenta,' nos 'balsamum' uertimus. dicitur autem quibus terra iudaea, quae nunc appellatur palaestina, abundet copiis frumento, balsamo, melle et oleo et resina, quae an iuda et Israel ad tyri nundinas deferuntur."[169]

- c. 414: Jerome, Letter 129: Ad Dardanum de Terra promissionis: "You may delineate the Promised Land of Moses from the Book of Numbers (ch. 34): as bounded on the south by the desert tract called Sina, between the Dead Sea and the city of Kadesh-barnea, [which is located with the Arabah to the east] and continues to the west, as far as the river of Egypt, that discharges into the open sea near the city of Rhinocolara; as bounded on the west by the sea along the coasts of Palestine, Phoenicia, Coele‑Syria, and Cilicia; as bounded on the north by the circle formed by the Taurus Mountains and Zephyrium and extending to Hamath, called Epiphany‑Syria; as bounded on the east by the city of Antioch Hippos and Lake Kinneret, now called Tiberias, and then the Jordan River which discharges into the salt sea, now called the Dead Sea."[170][171]

- c. 430: Theodoret, Interpretatio in Psalmos (Theodoretus in notāre ad Psalmos):[172] "PSALMS. CXXXIII. A Song of the Ascents, by David. Lo, how good and how pleasant The dwelling of brethren —even together! As the good oil on the head, Coming down on the beard, the beard of Aaron, That cometh down on the skirt of his robes, As dew of Hermon —That cometh down on hills of Zion, For there Jehovah commanded the blessing —Life unto the age!"[173] [Per Psalm 133 (132), Theodoretus Cyrrhi Episcopus wrote the following commentary;] Like dew of Hermon falling on Mount Sion (v. 3). Again he changed to another image, teaching the advantage of harmony; he said it is like the dew carried down from Hermon to Sion. There is so much of it that the jars release drops. Hermon is a mountain —in Palestine, in fact— and some distance from the land of Israel.[174]

- c. 450: Theodoret, Ecclesiastical History: "The see of Caesarea, the capital of Palestine, was now held by Acacius, who had succeeded Eusebius."[175]

- c. 450: Proclus of Constantinople: "Iosuae Palaestinae exploratori cohibendi solis lunaeque cursum potestatem adtribuit."[176]

- c. 500: Tabula Peutingeriana (map)

- c. 500: Zosimus, New History: "Finding the Palmyrene army drawn up before Emisa, amounting to seventy thousand men, consisting of Palmyrenes and their allies, [Emperor Aurelian] opposed to them the Dalmatian cavalry, the Moesians and Pannonians, and the Celtic legions of Noricum and Rhaetia, and besides these the choicest of the imperial regiment selected man by man, the Mauritanian horse, the Tyaneans, the Mesopotamians, the Syrians, the Phoenicians, and the Palestinians, all men of acknowledged valour; the Palestinians besides other arms wielding clubs and staves."[177]

- c. 550: Madaba map, "οροι Αιγυπτου και Παλαιστινης" (the "border of Egypt and Palestine)

- c. 550: Christian Topography.

- 555: Cyril of Scythopolis, The Life of St. Saba.[178]

- c. 555: Procopius, Of the Buildings of Justinian:[179] "In Palestine there is a city named Neapolis, above which rises a high mountain, called Garizin. This mountain the Samaritans originally held; and they had been wont to go up to the summit of the mountain to pray on all occasions, not because they had ever built any temple there, but because they worshipped the summit itself with the greatest reverence."[180]

- c. 560: Procopius, The Wars of Justinian: "The boundaries of Palestine extend toward the east to the sea which is called the Red Sea."[181] Procopius also wrote that "Chosroes, king of Persia, had a great desire to make himself master of Palestine, on account of its extraordinary fertility, its opulence, and the great number of its inhabitants."[182][183]

Middle Ages

Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates period

- 629: Heraclius, In 629 Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony:[184][185] I.e. the so-called Fast of Heraclius, which immediately preceding Lent, forms the first week of the Great Fast. The origin of this fast is said to be as follows: that the emperor Heraclius, on his way to Jerusalem, promised his protection to the Jews of Palestine, but that on his arrival in the holy city, the schismatical patriarch and the Christians generally prayed him to put all the Jews to the sword, because they had joined the Persians shortly before in their sack of the city and cruelties towards the Christians. (Abu Salih the Armenian, Abu al-Makarim, ed. Evetts 1895, p. 39, Part 7 of Anecdota Oxoniensia: Semitic series Anecdota oxoniensia. Semitic series—pt. VII], at Google Books)

- c. 670: Adomnán, De Locis Sanctis, or the Travels of Arculf: "Que utique Hebron, ut fertur, ante omnes, non solum Palestíne, civitates condita fuerat, sed etiam universas Egyptiacas urbes in sua precessit conditione, que nunc misere monstratur destructa."[186] translated: "This Hebron, it is said, was founded before all the cities, not only of Palestine, but also preceded in its foundation all the cities of Egypt, although it has now been so miserably destroyed."[187][188]

- c. 700: Ravenna Cosmography

- c. 770: Thawr ibn Yazid, hadith, as quoted in Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Wasiti's Fada'il Bayt al-Muqaddas (c. 1019): "The most holy spot [al-quds] on earth is Syria; the most holy spot in Syria is Palestine; the most holy spot in Palestine is Jerusalem [Bayt al-maqdis]; the most holy spot in Jerusalem is the Mountain; the most holy spot in Jerusalem is the place of worship [al-masjid], and the most holy spot in the place of worship is the Dome."[189][190]

- c. 770: Hygeburg, The Life of Willibald: "Then, having visited the church of St. George at Diospolis [he passed] through Joppe, a coast town of Palestine, where Peter raised to life the widow Dorcas, and went along the shore of the Adriatic Sea, and adored the footsteps of our Lord at Tyre and Sidon. And then, crossing Mount Libanus, and passing through the coast town of Tripoli, he visited Damascus again, and came to Emmaus, a village of Palestine, which the Romans after the destruction of Jerusalem called, after the event of the victory, Nicopolis."[191][192]

- 810–815: Theophanes the Confessor, Chronicles: Since Muhammad was a helpless orphan, he thought it good to go to a rich woman named Khadija ...to manage her camels and conduct her business in Egypt and Palestine... When he [Muhammad] went to Palestine he lived with both Jews and Christians, and hunted for certain writings among them.[193]

- c. 870: Ibn Khordadbeh, Book of Roads and Kingdoms: "Filastin Province 500,000 dinars of taxes" (c. 864)[194][195]

- c. 870: al-Baladhuri, Conquests of the Lands Wrote that the main towns of the district, following its conquest by the Rashidun Caliphate, were Gaza, Sebastia (Sebastiya), Nablus, Caesarea, Ludd, Yibna, Imwas, Jaffa, Rafah, and Bayt Jibrin.[194]

- 874: Musa ibn Sahl al-Ramli, Man nazala Filastin min al-sahaba [On the Prophetic Companions who settled in Palestine], the first known Islamic history of Syria in whole or part.[196]

- c. 880: Qudama ibn Ja'far, Kitab Al Kharaj (The Book of the Land Tax): Filastin Province, 195,000 dinars (c. 820)

- 891: Ya'qubi, Book of Lands: "Of the Jund Filastin, the ancient capital was Lydda. The Caliph Sulayman subsequently founded the city of Ramla, which he made the capital.... The population of Palestine consists of Arabs of the tribes of Lakhm, Judham, Amilah, Kindah, Kais and Kinanah"[194][195]

- c. 900: Limits of the Five Patriarchates: "The first See and the first patriarchate is of Jerusalem, James, the brother of God and apostle and eyewitness, and minister of the word and secrets of secrets and hidden mysteries, contains the whole Palestine a country until Arabia." (Πρῶτος θρόνος καὶ πρώτη πατριαρχία Ἱεροσολύμων, Ἱακώβου τοῦ ἀδελφοθέου καὶ ἀποστόλου, αὐτόπτου καί ὑπηρέτου τοῦ λόγου γενομένου καὶ μύστου τῶν ἀπορρήτων καὶ ἀθεάτων αὐτοῦ μυστηρίων θεαμάτων, περιέχων πᾶσαν τὴν Παλαιστίνων χώραν ἄχρι Ἀραβίας)

- 903: Ibn al-Faqih, Concise Book of Lands[194][197]

- After 904: Unknown author, possibly al-Masudi, Akhbar al-zaman (The History of Time), "Among children [of] Cainan are Falestin and Ṣidā, who gave their name to two countries".[198]

- c. 913: Ibn Abd Rabbih[194][197]

- c. 930: Patriarch Eutychius of Alexandria, Eutychii Annales:[199][200][201] CHAPTER II: ADVERSITIES OF THE CHURCH.: 1 Persecutions of the Christians.: ...The Christians suffered less in this than in the preceding centuries. ...In the East especially in Syria and Palestine the Jews sometimes rose upon the Christians with great violence (Eutyrhius, Annales tom ii., p. 236, &c. Jo. Henr. Hottinger, Historia Orientalis, lib. i., c. id., p. 129, &c.) yet so unsuccessfully as to suffer severely for their temerity. (Mosheim 1847, p. 426, at Google Books)

- before 942: Saadia Gaon (892–942), the great Jewish rabbi and exegete, makes the classic Jewish Arabic translation of the Torah, translating the Hebrew פלשת Pleshet Philistia as פלסטין (using Judeo-Arabic) Filasṭīn, e.g. Exodus 15:14 סכאן פלסטין the inhabitants of Palestine[202]

- 943: Al-Masudi, The Meadows of Gold[194][203]

- c. 950: Alchabitius, Introduction to the Art of Judgments of the Stars[204]

Fatimid Caliphate period

- 951–978: Istakhri, Traditions of Countries and Ibn Hawqal, The Face of the Earth: "The provinces of Syria are Jund Filstin, and Jund al Urdunn, Jund Dimaskh, Jund Hims, and Jund Kinnasrin.... Filastin is the westernmost of the provinces of Syria... its greatest length from Rafah to the boundary of Lajjun... its breadth from Jaffa to Jericho.... Filastin is the most fertile of the Syrian provinces.... Its trees and its ploughed lands do not need artificial irrigation... In the province of Filastin, despite its small extent, there are about 20 mosques.... Its capital and largest town in Ramla, but the Holy City (of Jerusalem) comes very near this last in size"[194][197]

- 985: Al-Maqdisi, Description of Syria, Including Palestine: "And further, know that within the province of Palestine may be found gathered together 36 products that are not found thus united in any other land.... From Palestine comes olives, dried figs, raisins, the carob-fruit, stuffs of mixed silk and cotton, soap and kercheifs"[205]

- c. 1000: Suda encyclopedic lexicon: "Παλαιστίνη: ὄνομα χώρας. καὶ Παλαιστι̂νος, ὁ ἀπὸ Παλαιστίνης." / "Palestine: Name of a territory. Also [sc. attested is] Palestinian, a man from Palestine.[206]

- 1029: Rabbi Solomon ben Judah of Jerusalem, a letter in the Cairo Geniza, refers to the province of Filastin[207]

- 1047: Nasir Khusraw, Safarnama[194] / Diary of a Journey through Syria and Palestine: "This city of Ramlah, throughout Syria and the West, is known under the name of Filastin."[208][209]

- c. 1050: Beatus of Liébana, Beatus map, Illustrates the primitive Diaspora of the Apostles and is one of the most significant cartographic works of the European High Middle Ages.

- 1051: Ibn Butlan[194]

Crusaders period

- 1101: Nathan ben Jehiel, Arukh: The Lexico Aruch is a talmudical lexicon authored by Rabbi Nathan ben Jehiel, of Rome. The occurrence of פלסטיני Παλαιστίνη [Palestine] in the Genesis Rabbah is noted.[210]

- 1100–27: Fulcher of Chartres, Historia Hierosolymitana (1095–1127): "For we who were Occidentals have now become Orientals. He who was a Roman or a Frank has in this land been made into a Galilean or a Palestinian."[211]

- c. 1130, Fetellus, "The city of Jerusalem is situated in the hill-country of Judea, in the province of Palestine"[212]

- 1154: Muhammad al-Idrisi, Tabula Rogeriana or The Book of Pleasant Journeys into Faraway Lands[194][213]

- 1160: Abraham ibn Daud, Sefer ha-Qabbalah[214]

- 1173: Ali of Herat, Book of Indications to Make Known the Places of Visitations[194]

- 1177: John Phocas, A Brief Description of the Castles and Cities, from the City of Antioch even unto Jerusalem; also of Syria and Phoenicia, and of the Holy Places in Palestine[215][216]

- c. 1180: William of Tyre, Historia Hierosolymitana[217]

- 1185: Ibn Jubayr, The Travels of Ibn Jubayr[194]

Ayyubid and Mamluk periods

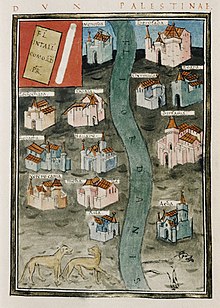

- 1220: Jacques de Vitry, History of Jerusalem: "And there are three Palestines, which are parts of Greater Syria. The first is that whose capital is Jerusalem, and this part is specially named Judaea. The second is that whose capital is Caesarea Philippi, which includes all the country of the Philistines. The third is that whose capital is Scythopolis, which at this day is called Bethshan. Moreover, both the Arabias are parts of Syria: the first is that whose capital is Bostrum; the second is that whose capital is Petra in the Wilderness."[218]

- 1225: Yaqut al-Hamawi, Dictionary of Geographies "Filastin is the last of the provinces of Syria towards Egypt. Its capital is Jerusalem. Of the principal towns are Ashkelon, Ramle, Gaza, Arsuf, Caesarea, Nablus, Jericho, Amman, Jaffa and Bayt Jibrin"[194]

- c.1250 Bar Hebraeus: "[The Syriac language] is divided into three dialects, one of the most elegant is Aramaea, the language of Edessa, Harran, and outer Syria; next adjoining to it is Palestinian, which is used in Damascus, the mountain of Lebanon, and inner Syria; and the vulgar Chaldean Nabataean, which is a dialect of Assyrian mountains and the districts of Iraq."[219]

- c. 1266 Abu al-Makarim, "The Churches and Monasteries of Egypt," Part 7 of Anecdota Oxoniensia: Semitic series Anecdota oxoniensia:[220] At the beginning of the caliphate [of Umar] George was appointed patriarch of Alexandria. He remained four years in possession of the see. Then when he heard that the Muslims had conquered the Romans, and had vanquished Palestine, and were advancing upon Egypt, he took ship and fled from Alexandria to Constantinople; and after his time the see of Alexandria remained without a Melkite patriarch for ninety seven years. (Abu al-Makarim c. 1895, p. 73, at Google Books)

- 1320: Marino Sanuto the Elder, Liber Secretorum Fidelium Crucis: "Also, the three [parts] of Palestine are called the Syrias, of which Syria Quinta is that Palestine which is properly called Philistym. Its chief city is Caesarea, beginning from Castrum Peregrinorum and extending south along the shore of the Mediterranean as far as Gaza in the south. Syria Sexta is the second Palestine whose chief city is Jerusalem including the hill country as far as the Dead Sea and the desert of Cadesbarne. Strictly this country is called Judaea, the name of a part being given to the whole. Syria Septima is the third Palestine whose chief city is Bethsan located under Mount Gelboe near the Jordan and which [contains] Galilee and the great plain of Esdrelon"[221]

- 1321: Abulfeda, A Sketch of the Countries: "The Nahr Abi Futrus is the river that runs near Ramla in Filastin"[194]

- 1322: Ishtori Haparchi, Sefer Kaftor Vaferach, mentions twice that Ramla is also known as Filastin

- 1327: Al-Dimashqi[194][222]

- 1338 Robert Mannyng The Chronicle

- c. 1350: Guidebook to Palestine (a manuscript primarily based on the 1285–1291 account of Christian pilgrim Philippus Brusserius Savonensis): "It [Jerusalem] is built on a high mountain, with hills on every side, in that part of Syria which is called Judaea and Palestine, flowing with milk and honey, abounding in corn, wine, and oil, and all temporal goods"[223]

- 1351: Jamal ad Din Ahmad, Muthir al Ghiram (The Exciter of Desire) for Visitation of the Holy City and Syria: "Syria is divided into five districts, namely: i. Filastin, whose capital is Aelia (Jerusalem), eighteen miles from Ramla, which is the Holy City, the metropolis of David and Solomon. Of its towns are Ashkelon, Hebron, Sebastia, and Nablus."[194]

- 1355: Ibn Battuta, Rihla[194] Ibn Battuta wrote that Ramla was also known as Filastin[224]

- 1355: Jacopo da Verona: Liber Peregrinationis: "Primo igitur sciendum est. quod in tota Asyria et Palestina et Egipto et Terra Sancta sunt multi cristiani sub potentia soldani subjugati solventes annuale tributum soldano multa et multa milia."[225][226]

- 1377: Ibn Khaldun, Muqaddimah: "Filastin Province taxes – 310,000 dinars plus 300,000 ratls of olive oil"[194]

- c. 1421: John Poloner "The land which we call the Holy Land came to be divided by lot among the twelve tribes of Israel, and with regard to one part was called the kingdom of Judaea ... with regard to the other part it was called the kingdom of Samaria... Both these kingdoms, together with the land of Philistim, were called Palestine, which was but a part thereof, even as Saxony and Lorraine are parts of Germany, and Lombardy and Tuscany are parts of Italy. And note that there are three Palestines. In the first, the capital city is Jerusalem, with all its hill country even to the Dead Sea and the wilderness of Kadesh Barnea. The second, whose capital city is Caesarea by the sea, with all the land of Philistim' beginning at Petra Incisa, and reaching as far as Gaza, was the Holy Land toward the south. The third is the capital city of Bethsan, at the foot of Mount Gilboa. This was once called Scythopolis, and is the place where the corpses of Saul's soldiers were hung up. This Palestine is properly called Galilee"[227]

- 1430: Abu-l Fida Ishak, Muthir al Ghiram (The Exciter of Desire)[194]

- 1459: Fra Mauro map

- 1470: Al-Suyuti:[194] "Syria is divided into five provinces, or sections:— First, Palestine, so called because first inhabited by Philistin son of Kusin, son of Muti, son of Yūmán, son of Yasith, son of Noah. Its first frontier town is on the Egyptian road Rafah, or Al Arish: next to this is Gaza, then Ramula, or Ramlat Phalistin. Of great cities in Palestine are, Elía, which is the Baitu-l-Mukaddas, eighteen miles from Ramlah (this holy city was the residence of David and Solomon), and Ascalon, and the city of Abraham, and Sebaste, and Neapolis. The whole extent of Palestine is, in length, two days’ journey to one who rides at the rate of a slow-moving beast; and in width, from Japha to Jericho, about as much."[228]

- 1480: Felix Fabri "Joppa is the oldest port, and the most ancient city of the province of Palestine"[229]

- 1482: Francesco di Niccolò Berlinghieri, Geographia, a treatise based upon Ptolemy's Geographica: map: Present-Day Palestine and the Holy Land

- 1492: Martin Behaim's "Erdapfel" globe

- 1496: Mujir al-Din al-'Ulaymi, The Glorious History of Jerusalem and Hebron:[194] According to Haim Gerber: "Among other things Mujir al-Din’s book is notable for its extensive use of the term "Palestine." The simple fact is that Mujir al-Din calls the country he lives in Palestine (Filastin), a term he repeats 22 times. One other name he uses for the country is the Holy Land, used as frequently as Palestine. No other names, such as Southern Syria, are ever mentioned... What area did he have in mind when speaking about Palestine? It stretched from Anaj, a point near al-Arish, to Lajjun, south of the Esdraelon valley. It was thus clearly equivalent to the Jund Filastin of classical Islam."[230]

Early modern period

Early Ottoman period

- 1536: Jacob Ziegler, Terrae sanctae, quam palestinam nominant, Syriae, Arabiae, Aegypti & Schondiae doctissima descriptio[232]

- 1540 Guillaume Postel: Syriae Descriptio[233]

- 1553: Pierre Belon, Observations, "De Plusieurs Arbes, Oiseaux, et autres choses singulieres, produictes en la terre de Palestine"[234]

- 1560: Geneva Bible, the first mass-produced English-language Bible, translates the Hebrew פלשת Pleshet as "Palestina" (e.g. Ex. 15:14; Isa. 14:29, 31) and "Palestina"[235]

- c. 1560: Ebussuud Efendi: Ebu Suud is asked in a fatwa, "What is the meaning of the term the Holy Land, arazi-i mukaddese?" His answer is that various definitions of the term exist, among them the whole of Syria, to Aleppo and Ariha in the north. Others equate it with the area of Jerusalem (al-Quds); still others equate it with the term "Palestine."[236]

- c. 1561: Anthony Jenkinson, published by Richard Hakluyt, The Principall Navigations, Voiages, and Discoveries of the English Nation: "I William Harborne, her Majesties Ambassadour, Ligier with the Grand Signior, for the affaires of the Levant Company in her Majesties name confirme and appoint Richard Forster Gentleman, my Deputie and Consull in the parts of Alepo, Damasco, Aman, Tripolis, Jerusalem, and all other ports whatsoever in the provinces of Syria, Palestina, and Jurie, to execute the office of Consull over all our Nation her Majesties subjects"[237]

- 1563: Josse van Lom, physician of Philip II of Spain: A treatise of continual fevers: "Therefore the Scots, English, Livonians, Danes, Poles, Dutch and Germans, ought to take less blood away in winter than in summer; on the contrary, the Portuguese, Moors, Egyptians, Palestinians, Arabians, and Persians, more in the winter than in summer"[238]

- 1563: John Foxe, Foxe's Book of Martyrs: "Romanus, a native of Palestine, was deacon of the church of Casearea at the time of the commencement of Diocletian's persecution."[239]

- c. 1565: Tilemann Stella, map: The Holy Land, the land of promise, which is a part of Syria, the parts that are called Palestina[240] at The Library of Congress

- 1565: Ignazio Danti, map: Anatolian peninsula and Middle East in the Palazzo Vecchio (Florence town hall)

- 1570: Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World),[241] map: Palestinæ

- 1570: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, folio 51[242]

- 1577: Holinshed's Chronicles: "The principal and chief cause I suppose and think to be, because that whereas the patriarch of Jerusalem named Heraclius came in an ambassage unto him, in the name and behalf of all the whole land of Palestine called the Holy Land, requesting that he would take upon him to be their help, and defending the same against the Saladin then king of Egypt and of Damascus"[243]

- 1583: Leonhard Rauwolf, Leonis Flaminii Itinerarium per Palaestinam Das ist, Eine mit vielen schönen Curiositaeten angefüllte Reiß-Beschreibung[244]

- 1591: Johannes Leunclavius: Historiae Musulmanae Turcorum Latin: "Cuzzimu barec ea ciuitas est Palæstinæ, quam veteres Hierosolyma dixerunt, Hebræi Ierusalem. Nomen hodiernum significa locum benedictum vel inclytum," translates as "Quds Barış is the city of the Palestinians, also known as Hierosolyma, in Hebrew, Jerusalem. The name means the holy one or the glorious one"[245]

- 1591: Giovanni Botero[246]

- 1594: Uri ben Shimon and Jakob Christmann (ed.): Calendarium Palaestinorum Et Universorum Iudaeorum... "Auctore Rabbi Ori filio Simeonis, Iudeo Palaestino" [Author Rabbi Uri son of Simeon, Palestinian Jew]"[247]

- 1596: Giovanni Antonio Magini, Geographia, Cosmographia, or Universal Geography: An atlas of Claudius Ptolemy's world of the 2nd century, with maps by Giovanni Antonio Magini of Padua,[248] map: Palaestina, vel Terra Sancta,[249] at Google Books

- c. 1600: Shakespeare: The Life and Death of King John: Scene II.1 "Richard, that robb'd the lion of his heart, and fought the holy wars in Palestine"[250] / Othello Scene IV.3: "I know a lady in Venice would have walked barefoot to Palestine for a touch of his [Lodovico's] nether lip."[251]

- 1607: Hans Jacob Breuning von Buchenbach, Enchiridion Orientalischer Reiß Hanns Jacob Breunings, von vnnd zu Buchenbach, so er in Türckey, benandtlichen in Griechenlandt, Egypten, Arabien, Palestinam, vnd in Syrien, vor dieser zeit verrichtet (etc.)[252]

- 1610: Douay–Rheims Bible, uses the name Palestine (e.g. Jer 47:1; Ez 16:"1 And the word of the Lord came to me, saying: 2 Son of man, make known to Jerusalem her abominations. 3 And thou shalt say: Thus saith the Lord God to Jerusalem:...56 as it is at this time, making thee a reproach of the daughters of Syria, and of all the daughters of Palestine round about thee, that encompass thee on all sides.")

- 1611: King James Version, translates the Hebrew פלשת Pleshet as "Palestina" (e.g. Ex. 15:14; Isa. 14:29, 31) and "Palestine" (e.g. Jl 3:4)

- 1613: Salomon Schweigger, Ein newe Reyßbeschreibung auß Teutschland nach Constantinopel und Jerusalem[253]

- 1616: Pietro Della Valle: Viaggi di Pietro della Valle il Pellegrino[254]

- 1624: Francis Bacon, New Atlantis, "The Phoenicians, and especially the Tyrians, had great fleets; so had the Carthaginians their colony, which is yet farther west. Toward the east the shipping of Egypt, and of Palestine, was likewise great."[255]

- 1625: Samuel Purchas, Hakluytus Posthumus, "And lastly, in the more Eastward, and South parts, as in that part of Cilicia, that is beyond the River Piramus, in Syria, Palestine, Ægypt and Lybia, the Arabian Tongue hath abolished it"[256]

- 1637: Philipp Cluverius, Introductionis in universam Geographiam (Introduction to World Geography),[257][258] map: Palaestina et Phienice cum parte Coele Syria[259]

- 1639: Thomas Fuller, The Historie of the Holy Warre[260] also A Pisgah sight of Palestine[261][262][263]

- 1642: Vincenzo Berdini, Historia dell'antica, e moderna Palestina, descritta in tre parti.[264]

- 1647: Sadiq Isfahani, The Geographical Works of Sadik Isfahani: "Filistin, a region of Syria, Damascus, and Egypt, comprising Ramla, Ashkelon, Beit al Mukuddes (Jerusalem), Kanaan, Bilka, Masisah, and other cities; and from this province is denominated the "Biaban-i Filistin" (or Desert of Palestine), which is also called the "Tiah Beni-Israil""[265]

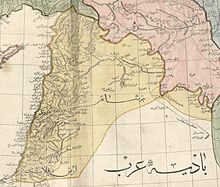

- 1648–57: Kâtip Çelebi, Cihânnümâ (printed by Ibrahim Muteferrika in 1729); the first detailed Ottoman mapping of its Syrian provinces: "The clime of Syria is divided into a number of provinces (eyālet). One is Shām, [M 562] which consists of Damascus. The others are Jerusalem, Tripoli, Sidon, and Aleppo. Syria is then subdivided into ten sanjaks: Damascus, which is the pasha sanjak, Jerusalem, Gaza, Nablus, ʿAj[l]ūn, Lajjūn, Ṣafad, Sidon, Beirut, and Ḳarak and Shawbak. However, Jerusalem, Gaza, Nablus, ʿAjlūn and Ṣafad are a separate group. The noblest of the administrative divisions of Syria is Palestine. Let me begin with it because it includes the district of Jerusalem... Palestine is composed of two sanjaks: Gaza and Jerusalem. Borders: In the southwest the border goes from the Mediterranean and al-ʿArīsh to the Wilderness of the Israelites [Tīh = Sinai]. In the southeast it is the Dead Sea [Bahar Lut] and the Jordan River. In the north it goes from the Jordan River to the borders of Urdun as far as Caesarea."[266][267]

- c. 1649: Evliya Çelebi, Travels in Palestine: "All chronicles call this country the Land of Palestine"[268]

- 1649: Johann Heinrich Alsted, Scientiarum Omnium Encyclopaedia:[269] XI. Palestina lacus tres sunt, è quibus duo posteriores natissimi sum historia sacra (11. Palestine has three lakes, the later two of these I relate to Biblical history) (Alsted 1649, p. 560 at Google Books)

⟨1650⟩

- 1655: Christoph Heidmann, Palaestina: CAPUT V. - De Urbibus Maritimis Philistaeorum, et aliis ad limitem usq AEgypti. Palaestina propriè dicta est ea terrae sanctae pars, quae ad mare Mediterraneum sita urbes aliquot illustres, & reges potentes olim habuit: quod antè etiam indicatum. Populus Philistini sive Philistaei, aut Philistiim appellati, corruptè Palaestini, Graecis, ut & Sulpicio Severo, ???, id est peregrini Ita gentes vocabant à religione & ritibus Iudaeorum aver fas. 2. Hieronymus Philistiim prius Chasloím appellatos ait, posteros Cham, quos nos inquit, corrupté Palaestinos dicimus 3. Fines ejus â Castro peregrinorum seu Dor, aut Caesarea Palaestinae, vel turre Stratonis, usque Gazam, aut torrentem AEgypti, extendir Adrichomius, aitque Enakim inter cos, id est gigantes fuisse robustissimos.[270]

- 1660: Manuel de Almeida, Historia de Etiopía a Alta ou Abassia (reprinted in 1710): "This same name [Ethiopia] also denotes those Countries lying along the Red Sea, on the side of Arabia, as far as Palastine, which in Holy Writ are call'd Ethiopia."[271]

- 1664: Jean de Thévenot, Relation d'un voyage fait au Levan: Acre est une ville de Palestine située au bord de la mer, elle s'appelloit anciennement Acco.[272]

- c. 1670: Khayr al-Din al-Ramli, al-Fatawa al-Khayriyah: According to Haim Gerber "on several occasions Khayr al-Din al-Ramli calls the country he was living in Palestine, and unquestionably assumes that his readers do likewise. What is even more remarkable is his use of the term "the country" and even "our country" (biladuna), possibly meaning that he had in mind some sort of a loose community focused around that term."[273] Gerber describes this as "embryonic territorial awareness, though the reference is to social awareness rather than to a political one."[236]

- c. 1670: Salih b. Ahmad al-Timurtashi, The Complete Knowledge of the Limits of the Holy Land and Palestine and Syria (Sham).[274]

- 1677: Olfert Dapper, Precise Description of whole Syria, and Palestine or Holy Land, 'Naukeurige Beschrijving van Gantsch Syrie en Palestijn of Heilige Lant'[275]

- 1681: Olfert Dapper, Asia, oder genaue und gründliche Beschreibung des ganzen Syrien und Palestins, oder Gelobten Landes (Asia, or accurate and thorough description of all Syria and Palestine, or the promised land. (German text; Amsterdam 1681 & Nürnberg 1688)): Gewisse und Gründliche Beschreibung des Gelobten Landes / sonsten Palestina geheissen (Certain and thorough description of the Promised Land / otherwise called Palestine)[276]

- c. 1682: Zucker Holy Land Travel Manuscript: Antiochia die vornehmste und hauptstadt des ganzen Syrien (und auch Palestinia) [Antioch the capital and chief of the whole Syria (and Palestine)]. (p. 67 Calesyria[277])

- 1683: Alain Manesson Mallet, Description De l'Univers:[278] map: Syrie Moderne at Archive.org.

- 1688: John Milner, A Collection of the Church-history of Palestine:[279] Hitherto of Places, now follows an account of the Persons concerned in the Church-History of Palestine. (Milner 1688, p. 19, at Google Books)

- 1688: Edmund Bohun, A Geographical Dictionary, Representing the Present and Ancient Names of All the Countries:[280] Jerusalem, Hierosolyma, the Capital City of Palestine, and for a long time of the whole Earth; taken notice of by Pliny, Strabo, and many of the Ancients. (Bohun 1688, p. 353, at Google Books)

- 1693: Patrick Gordon (Ma FRS), Geography Anatomiz'd:[281][282] Palestine, or Judea, Name.] This Country ...is term'd by the Italians and Spaniards, Palestina; by the French, Palestine; by the Germans Palestinen, or das Gelobte Land; by the English, Palestine, or the Holy Land. (Gordon 1704, p. 290, at Google Books)

- 1696: Matthaeus Hiller, Philistaeus exul, s. de origine, diis et terra Palaestinorum diss.[283]

- 1703: Henry Maundrell, A journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem at Easter, A.D. 1697: For the husbanding of these mountains, their manner was to gather up the stones, and place them in several lines, along the sides of the hills, in form of a wall. By such borders, they supported the mould from tumbling, or being washed down; and formed many beds of excellent soil, rising gradually one above another, from the bottom to the top of the mountains. Of this form of culture you see evident footsteps, wherever you go in all the mountains of Palestine. Thus the very rocks were made fruitful And perhaps there is no spot of ground in this whole land, that was not formerly improved, to the production of something or other, ministering to the sustenance of human life.[284]

- 1704: Martin Baumgarten, Travels through Egypt, Arabia, Palestine, and Syria, 'A Collection of Voyages and Travels: Some Now First Printed from Original Manuscripts': Gaza, or Gazera, was once a great and strong City, and one of the five principal ones in Palestine, and was call'd so by the Persians.[285]

- 1709: Matthäus Seutter, map: Deserta Aegypti, Thebaidis, Arabiae, Syriae etc. ubi accurata notata sunt loca inhabitata per Sanctos Patres Anachoretas at The Library of Congress

- 1714: Johann Ludwig Hannemann, Nebo Chemicus Ceu Viatorium Ostendens Viam In Palestinam Auriferam[286]

- 1714: Adriaan Reland, Hadriani Relandi Palaestina ex monumentis veteribus illustrata: CAPUT VII. DE NOMINE PALAESTINAE. [i.]Regio omnis quam Judaei incoluerunt nomen Palaestinae habuit. [ii.]Hebraeorum scriptores, Philo, Josephus, & alii hoc nomine usi. [iii.] פלסטיני in antiquissimis Judaeorum scriptis. (Chapter 7. Palestine. [i.]The country that the Jews inhabited was called Palestine. [ii.]The Hebrew Scriptures, Philo, Josephus, et al. who have used this name. [iii.] פלסטיני [Palestinian] in ancient Jewish writings.) [...] Chapter 8. Syria-Palaestina, Syria, and Coelesyria. Herodotus described Syria-Palaestina. The Palestinian southern boundary is lake Serbonian. Jenysus & Jerusalem are cities of Palestine, as is Ashdod and Ashkelon. Palestine is different from Phoenice.[287] map: Palaestina prima.

- 1717: Laurent d'Arvieux, Voyage dans la Palestine[288]

- 1718: Isaac de Beausobre, David Lenfant, Le Nouveau Testament de notre seigneur Jesus-Christ: On a déja eu occasion de parler des divers noms, que portoit autrefois la Terre d Israël, Ici nous désignerons sous le nom de Palestine qui est le plus commun. (We previously spoke of the various names for the Land of Israel, ...Now we will refer to the Land of Israel by the name of Palestine which is the most common)[289][290]

- 1718: John Toland, Nazarenus: or Jewish, Gentile and Mahometan Christianity:[291] NOW if you'll suppose with me (till my proofs appear) this pre-eminence and immortality of the Mosaic Republic in its original purity, it will follow; that, as the Jews known at this day, and who are dispers'd over Europe, Asia, and Africa, with some few in America, are found by good calculation to be more numerous than either the Spaniards (for example) or the French: so if they ever happen to be resettl'd in Palestine upon their original foundation, which is not at all impossible; they will then, by reason of their excellent constitution, be much more populous, rich, and powerful than any other nation now in the world. I Wou'd have you consider, whether it be not both the interest and duty of Christians to assist them in regaining their country. But more of this when we meet. I am with as much respect as friendship (dear Sir) ever yours, [signed] J.T. [at] Hague 1719 (Toland 1718, p. 8 at Google Books).

- 1720: Richard Cumberland, Sanchoniatho's Phoenician History: That the Philistines who were of Mizraim's family, were the first planters of Crete. ...I observe that in the Scripture language the Philistines are call'd Cerethites, Sam. xxx. 14, 16. Ezek. xxv. 16. Zeph. ii. 5. And in the two last of these places the Septuagint translates that word Cretes. The name signifies archers, men that in war were noted for skill in using bows and arrows. ...[I] believe that both the people and the religion, (which commonly go together) settled in Crete, came from these Philistines who are originally of Ægyptian race.[292]

- 1730: Joshua Ottens, map: Persia (Iran, Iraq, Turkey)[293]

- 1736: Herman Moll, map: Turkey in Asia[294]

- 1737: Isaac Newton, Interpretation of Daniel's Prophecies[295]

- 1738: D. Midwinter, A New Geographical Dictionary ... to which is now added the latitude and longitude of the most considerable cities and towns,&c., of the world: Jerusalem, Palestine, Asia – [Latitude 32 44 N] – [Longitude 35 15 E][296]

- 1741: William Cave, Scriptorum eccleriasticorum historia literaria[297]

- 1741: Jonas Korten, Jonas Kortens Reise nach dem weiland Gelobten nun aber seit 1700 Jahren unter dem Fluche ligenden Lande, wie auch nach Egypten, dem Berg Libanon, Syrien und Mesopotamien.[298]

- 1743: Richard Pococke: Description of the East

- 1744: Charles Thompson (fict. name.), The travels of the late Charles Thompson esq.: I shall henceforwards, without Regard to geographical Niceties and Criticisms, consider myself as in the Holy Land, Palestine or Judea; which Names I find used indifferently, though perhaps with some Impropriety, to signify the same Country.[299]

- 1744: Johann Christoph Harenberg, La Palestine ou la Terre Sainte:[300] Map: Palaestina seu Terra olim tum duodecim tribubus distributa, tum a Davide et Salomone, et Terra Gosen Archived 2015-07-01 at the Wayback Machine at the National Library of Israel.

- 1746: Modern History Or the Present State of All Nations: "Palestine, or the Holy Land, sometimes also called Judea, is bound by Mount Libanus on the north; by Arabia Deserta on the east; by Arabia Petrea on the south; and by the Mediterranean Sea on the west"[301]

- 1747: The modern Gazetteer: "Palestine, a part of Asiatic Turkey, is situated between 36 and 38 degrees of E longitude and between 31 and 34 degrees of N latitude, bounded by the Mount Libanus, which divides it from Syria, on the North, by Mount Hermon, which separates it from Arabia Deserta, on the East, by the mountains of Seir, and the deserts of Arabia Petraea, on the South, and by the Mediterranean Sea on the West, so that it seems to have been extremely well secured against foreign invasions."[302]

⟨1750⟩

- 1750: Vincenzo Ludovico Gotti, Veritas religionis christianae contra atheos, polytheos, idololatras, mahometanos, [et] judaeos ...[303]

- 1751: The London Magazine[304]

- 1759: Johannes Aegidius van Egmont, John Heyman (of Leydon), Travels Through Part of Europe, Asia Minor, the Islands of the Archipelago, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Mount Sinai, &c. &c.:[305] The Jews of Jerusalem are divided into three sects, the Karaites, who adhere to the letter of the Scripture, without admitting any comments, or glosses; the Rabbinists, who receive for indubitable truths, all the comments and traditions so well known in the world, and are hence much more superstitious than the former; the third are the Askenites, who come from Germany, and are known among their brethren by the name of new converts; not being descended from the twelve tribes. [...] Besides these three sects, there is in the country of Palestine a fourth sort of Jews, but sworn enemies to the others, I mean the Samaritans; these have frequently endeavoured by the arts of bribery to obtain the privilege of living in Jerusalem, and in order to accomplish this design, have lavished away above five hundred purses. (Aegidius and Heyman 1759, p. 389 & p. 390 at Google Books)

- 1763: Voltaire, The Works of M. de Voltaire: Additions to the essay on general history:[306] The same may be said of the prohibition of eating pork, blood, or the flesh of beasts dying of any disease; these are precepts of health. The flesh of swine in particular is a very unwholesome food in those hot countries, as well as in the Palestine, that lies in their neighbourhood. When the Mahometan religion spread itself into colder climates, this abstinence ceased to be reasonable; but nevertheless did not cease to be in force. (Voltaire, ed. Smollett and Francklin 1763, p. 42 at Google Books)

- 1765: Christoph Schrader, Gebhardt Theodor Meier, Tabulae chronologicae a prima rerum origine et inde ad nostra tempora: 225 CE. Jews were allowed to live in Palestine.[307]

- 1778: Denis Diderot, Encyclopédie, "Palestine."[308]

- 1779: George Sale, Ancient Part of Universal History: "How Judæa came to be called also Phœnice, or Phœnicia, we have already shewn in the history of that nation. At present, the name of Palestine is that which has most prevailed among the Christian doctors, Mahommedan and other writers. (See Reland Palestin. illustrat.)"[309]

- 1782: Johann Georg Meusel, Bibliotheca historica:[310]

- Sectio I. Scriptores de Palaestina

- I. Scriptores universales

- A. Itineraria et Topographiae a testibus oculatis conditae. 70

- B. Geographi Palaestinae recentiores, qui non ipsi terram istam perlustrarunt, sed ex itinerariis modo recensitis aliisque fontibus sua depromserunt. 94

- II. Scriptores de Palaestina Speciales

- A. Scriptores de aere folo et fetilitate Palaestinae. 110

- [...]

- E. Scriptores de variis argumentis aliis hue pertinentibus. 117

- I. Scriptores universales

- 1788: Constantine de Volney, Travels through Syria and Egypt, in the years 1783, 1784, and 1785:[311][312] Palestine abounds in sesamum from which oil is procured and doura as good as that of Egypt. ...Indigo grows without cultivating on the banks of the Jordan, in the country of Bisan. ...As for trees, the olive-tree of Provence grows at Antioch and Ramla, to the height of the beech. ...there were in the gardens of Yaffa, two plants of the Indian cotton-tree which grow rapidly, nor has this town lost its lemons, its enormous citrons, or its water melons. ...Gaza produces dates like Mecca, and pomegranates like Algiers.[313]

- 1791: Giovanni Mariti, Travels Through Cyprus, Syria, and Palestine; with a General History of the Levant. Translated from the Italian:[314] OF THE HEBREWS. TWO kinds of Jews are found in Syria and Palestine; one of which are originally from these countries, and the other foreigners. A diversity of religious systems divides them, as well as all the other nations on the earth, who give too much importance to the spirit of theological dispute. They are distinguished into Talmudists, and Caraites, or enemies of the Talmud: and such is the inveterate hatred of the latter against the rest of their brethren, that they will not suffer them to be interred in the same burying-grounds, where all mankind in the like manner must moulder in-to dust.[315]

- 1794: Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville, map: A New Map of Turkey in Asia[316]

- 1799: Pierre Jacotin, Napoleon's director of surveyancing, begins work on the "Jacotin Map": The region is labelled "Palestine" in French and فلسطين أو أرض قدس ("Palestine or Holy Land") in Arabic[317]

- 1801: Thomas Roberts (toxophilite), The English Bowman, Or Tracts on Archery: "The Philistines, indeed, are frequently noticed in sacred history, as men very skilful in the use of the bow. And to this ancient people, who appear to have been a very warlike nation, the invention of the bow and arrow has been ascribed. Universal Hist. (anc. part) vol. 2. p. 220."[318]

- 1803: Cedid Atlas, showing the term ارض فلاستان ("Land of Palestine")

Modern period

Late Ottoman period

- 1805: Palestine Association founded

- 1806: Lant Carpenter, An Introduction to the Geography of the New Testament:[319] He brought out in 1806 a popular manual of New Testament geography.[320][321] (Levant map, p. PA4, at Google Books)

- 1809: Reginald Heber, Palestine: a Poem

- 1811: François-René de Chateaubriand, Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem (Travels in Greece, Palestine, Egypt, and Barbary, during the years 1806 and 1807 [trans. 1812]): As to travellers of very recent date such as Muller, Vanzow, Korte, Bescheider, Mariti, Volney, Niebuhr, and Brown, they are almost totally silent respecting the holy places. The narrative of Deshayes (1621), who was sent to Palestine by Louis XIII, appears therefore to me the fittest to be followed.[322][323]

- 1812: William Crotch, Palestine (an oratorio)

- 1819: George Paxton, Illustrations of the Holy Scriptures: in three Parts.[324]

1. From the Geography of the East.[325]

2. From the Natural History of the East.[326][327]

3. From the Customs of Ancient and Modern Nations.[327]

- Females of distinction in Palestine, and even in Mesopotamia, are not only beautiful and well-shaped, but, in consequence of being always kept from the rays of the sun, are very fair.[328]

- 1819: Abraham Rees, Palestine & Syria, The Cyclopædia: Or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature: Palestine, says Volney, is a district independent of every Pachalic. Sometimes it has governors of its own, who reside at Gaza under the title of Pachas; but it is usually, as at present, divided into three appanages, or Melkana, viz. Yafa, Loudd, and Gaza. The former belongs to the Walda or sultana mother. The captain Pacha has received the two others as a recompence for his services, and a reward for the head of Daher. He farms them to an aga, who resides at Ramla, and pays him two hundred and fifteen purses for them, viz. one hundred and eighty for Gaza and Ramla, and thirty-five for Loudd.[329] [...] The ground is tilled by asses or cows, rarely by oxen. In districts like Palestine, exposed to the Arabs, the countryman must sow with a musket in his hand. The corn before it changes colour, is reaped, but concealed in caverns. The whole industry of the peasant is limited to a supply of his immediate wants; and to procure a little bread, a few onions, a wretched blue shirt, and a bit of woollen, much labour is not necessary.[330]

- 1822: Conrad Malte-Brun, Universal Geography, Or, a Description of All the Parts of the World, on a New Plan: BOOK XXVII. TURKEY IN ASIA. PART II. Including Armenia Mesopotamia and Irac Arabi. The eastern provinces of the Turkish empire in Asia form three natural divisions: the region of Orontes and Libanus, or Syria and Palestine; that of the sources of the Euphrates and of the Tigris, or Armenia with Koordistan; finally, the region of Lower Euphrates, or Al-Djesira with Irac-Arabi, otherwise Mesopotamia, and Babylonia. We shall here connect the two divisions on the Euphrates, without confounding them. Syria will be described in a separate book.[331] [...] Population. It would be vain to expect a near approximation to the truth in any conjectures which we might indulge respecting the population of a state in which registers and a regular census are unknown. Some writers estimate that of European Turkey at twenty-two, while others have reduced it to eight millions (Bruns. Magas. Géograph. I. cah. 1. p. 68–74. compared with Ludeck's Authentic Account of the Ottoman Empire. Etton's View and de Tott's Memoirs.), and both assign equally plausible grounds for their opinions. Respecting Asiatic Turkey, the uncertainty, if not still greater, is at least more generally acknowledged. Supposing the houses to be as thinly scattered as in the less populous parts of Spain, the population of all Turkey, in Europe, Asia, and Africa, may amount to 25 or 30 millions, of which one half belongs to Asia. Under the want of any thing like positive evidence, we shall not deviate far from probability in allowing to Anatolia, five millions; to Armenia, two; to Koordistan, one; to the pashâlics of Bagdat, Mosul, and Diarbekir, one and a half; and to Syria 1,800,000, or at most two millions.[332]