Atrial flutter

| Atrial flutter | |

|---|---|

| |

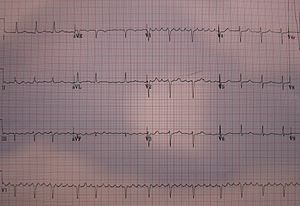

| Atrial flutter with varying A-V conduction (5:1 and 4:1) | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Diagnostic method | Electrocardiography |

Atrial flutter (AFL) is a common abnormal heart rhythm that starts in the atrial chambers of the heart.[1] When it first occurs, it is usually associated with a fast heart rate and is classified as a type of supraventricular tachycardia.[2] Atrial flutter is characterized by a sudden-onset (usually) regular abnormal heart rhythm on an electrocardiogram (ECG) in which the heart rate is fast. Symptoms may include a feeling of the heart beating too fast, too hard, or skipping beats, chest discomfort, difficulty breathing, a feeling as if one's stomach has dropped, a feeling of being light-headed, or loss of consciousness.

Although this abnormal heart rhythm typically occurs in individuals with cardiovascular disease (e.g., high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, and cardiomyopathy) and diabetes mellitus, it may occur spontaneously in people with otherwise normal hearts. It is typically not a stable rhythm, and often degenerates into atrial fibrillation (AF).[3] But rarely does it persist for months or years. Similar to the abnormal heart rhythm atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter also leads to poor contraction of the atrial chambers of the heart. This leads to the pooling of the blood in the heart and can lead to the formation of blood clots in the heart which poses a significant risk of breaking off and traveling through the bloodstream resulting in strokes.

A supraventricular tachycardia with a ventricular heart rate of 150 beats per minute is suggestive (though not necessarily diagnostic) of atrial flutter. Administration of adenosine in the vein (intravenously) can help medical personnel differentiate between atrial flutter and other forms of supraventricular tachycardia.[2] Immediate treatment of atrial flutter centers on slowing the heart rate with medications such as beta blockers (e.g., metoprolol) or calcium channel blockers (e.g., diltiazem) if the affected person is not having chest pain, has not lost consciousness, and if their blood pressure is normal (known as stable atrial flutter). If the affected person is having chest pain, has lost consciousness, or has low blood pressure (unstable atrial flutter), then an urgent electrical shock to the heart to restore a normal heart rhythm is necessary. Long-term use of blood thinners (e.g., warfarin or apixaban) is an important component of treatment to reduce the risk of blood clot formation in the heart and resultant strokes.[3][4] Medications used to restore a normal heart rhythm (antiarrhythmics) such as ibutilide effectively control atrial flutter about 80% of the time when they are started but atrial flutter recurs at a high rate (70–90% of the time) despite continued use.[1] Atrial flutter can be treated more definitively with a technique known as catheter ablation. This involves the insertion of a catheter through a vein in the groin which is followed up to the heart and is used to identify and interrupt the electrical circuit causing the atrial flutter (by creating a small burn and scar).

Atrial flutter was first identified as an independent medical condition in 1920 by the British physician Sir Thomas Lewis (1881–1945) and colleagues.[5] AFL is the second most common pathologic supraventricular tachycardia but occurs at a rate less than one-tenth of the most common supraventricular tachycardia (atrial fibrillation).[2][3] The overall incidence of AFL has been estimated at 88 cases per 100,000 person-years. The incidence of AFL is significantly lower (~5 cases/100,000 person-years) in those younger than age 50 and is far more common (587 cases/100,000 person-years) in those over 80 years of age.[3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]While atrial flutter can sometimes go unnoticed, its onset is often marked by characteristic sensations of the heart feeling like it is beating too fast or hard. Such sensations usually last until the episode resolves, or until the heart rate is controlled.[6][citation needed]

Atrial flutter is usually well-tolerated initially (a high heart rate is for most people just a normal response to exercise); however, people with other underlying heart diseases (such as coronary artery disease) or poor exercise tolerance may rapidly develop symptoms, such as shortness of breath, chest pain, lightheadedness or dizziness, nausea and, in some patients, nervousness and feelings of impending doom.[7][citation needed]

Prolonged atrial flutter with fast heart rates may lead to decompensation with loss of normal heart function (heart failure). This may manifest as exercise intolerance (exertional breathlessness), difficulty breathing at night, or swelling of the legs and/or abdomen.[8][citation needed]

Complications

[edit]Although often regarded as a relatively benign heart rhythm problem, atrial flutter shares the same complications as the related condition atrial fibrillation. There is paucity of published data directly comparing the two, but overall mortality in these conditions appears to be very similar.[9]

Rate-related

[edit]Rapid heart rates may produce significant symptoms in patients with pre-existing heart disease and can lead to inadequate blood flow to the heart muscle and even a heart attack.[1]

In rare situations, atrial flutter associated with a fast heart rate persists for an extended period of time without being corrected to a normal heart rhythm and leads to a tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.[1] Even in individuals with a normal heart, if the heart beats too quickly for a prolonged period of time, this can lead to ventricular decompensation and heart failure.[citation needed]

Clot formation

[edit]Because there is little if any effective contraction of the atria, there is stasis (pooling) of blood in the atria. Stasis of blood in susceptible individuals can lead to the formation of a thrombus (blood clot) within the heart. A thrombus is most likely to form in the atrial appendages. A blood clot in the left atrial appendage is particularly important as the left side of the heart supplies blood to the entire body through the arteries. Thus, any thrombus material that dislodges from this side of the heart can embolize (break off and travel) to the brain's arteries, with the potentially devastating consequence of a stroke. Thrombus material can, of course, embolize to any other portion of the body, though usually with a less severe outcome.[10]

Sudden cardiac death

[edit]Sudden death is not directly associated with atrial flutter. However, in individuals with a pre-existing accessory conduction pathway, such as the bundle of Kent in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, the accessory pathway may conduct activity from the atria to the ventricles at a rate that the AV node would usually block. Bypassing the AV node, the atrial rate of 300 beats/minute leads to a ventricular rate of 300 beats/minute (1:1 conduction). Even if the ventricles are able to sustain a cardiac output at such a high rate, 1:1 flutter with time may degenerate into ventricular fibrillation, causing hemodynamic collapse and death.[11]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Atrial flutter is caused by a re-entrant rhythm. This usually occurs along the cavo-tricuspid isthmus of the right atrium though atrial flutter can originate in the left atrium as well. Typically initiated by a premature electrical impulse arising in the atria, atrial flutter is propagated due to differences in refractory periods of atrial tissue. This creates electrical activity that moves in a localized self-perpetuating loop, which usually lasts about 200 milliseconds for the complete circuit. For each cycle around the loop, an electric impulse results and propagates through the atria.[citation needed]

The impact and symptoms of atrial flutter depend on the heart rate of the affected person. Heart rate is a measure of ventricular rather than atrial activity. Impulses from the atria are conducted to the ventricles through the atrio-ventricular node (AV node). In a person with atrial flutter, a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) will demonstrate the atrial chambers of the heart contracting at a rate of 280–300 beats per minute whereas the ventricular chambers of the heart typically beat at a rate of 140–150 beats per minute.[2] Due primarily to its longer refractory period, the AV node exerts a protective effect on heart rate by blocking atrial impulses in excess of about 180 beats/minute, for the example of a resting heart rate. (This block is dependent on the age of the patient, and can be calculated roughly by subtracting patient age from 220). If the flutter rate is 300/minute only half of these impulses will be conducted, giving a ventricular rate of 150/minute, or a 2:1 heart block. The addition of rate-controlling drugs or conduction system disease can increase this block substantially[12]

Diagnosis

[edit]Typical atrial flutter is recognized on an electrocardiogram by presence of characteristic "flutter waves" at a regular rate of 200 to 300 beats per minute. Flutter waves may not be evident on an ECG in atypical forms of atrial flutter. Individual flutter waves may be symmetrical, resembling p-waves, or maybe asymmetrical with a "sawtooth" shape, rising gradually and falling abruptly or vice versa. If atrial flutter is suspected clinically but is not clearly evident on ECG, acquiring a Lewis lead ECG may be helpful in revealing flutter waves.[citation needed]

Classification

[edit]There are two types of atrial flutter, the common type I and rarer type II.[13] Most individuals with atrial flutter will manifest only one of these. Rarely someone may manifest both types; however, they can manifest only one type at a time.[citation needed]

Type I

[edit]

Type I atrial flutter, also known as common atrial flutter or typical atrial flutter, has an atrial rate of 240 to 340 beats/minute. However, this rate may be slowed by antiarrhythmic agents.[citation needed]

The reentrant loop circles the right atrium, passing through the cavo-tricuspid isthmus – a body of fibrous tissue in the lower atrium between the inferior vena cava, and the tricuspid valve.[1] Type I flutter is further divided into two subtypes, known as counterclockwise atrial flutter and clockwise atrial flutter depending on the direction of current passing through the loop.[1]

- Counterclockwise atrial flutter (known as cephalad-directed atrial flutter) is more commonly seen. The flutter waves in this rhythm are inverted in ECG leads II, III, and aVF.[1]

- The re-entry loop cycles in the opposite direction in clockwise atrial flutter, thus the flutter waves are upright in II, III, and aVF.[1]

Type II

[edit]Type II (atypical) atrial flutter follows a significantly different re-entry pathway to type I flutter, and is typically faster, usually 340–350 beats/minute.[14] Atypical atrial flutter rarely occurs in people who have not undergone previous heart surgery or previous catheter ablation procedures. Left atrial flutter is considered atypical and is common after incomplete left atrial ablation procedures.[15] Atypical atrial flutter originating from the right atrium and heart's septum have also been described.[citation needed]

Management

[edit]In general, atrial flutter should be managed in the same way as atrial fibrillation. Because both rhythms can lead to the formation of a blood clot in the atrium, individuals with atrial flutter usually require some form of anticoagulation or antiplatelet agent. Both rhythms can be associated with dangerously fast heart rates and thus require medication to control the heart rate (such as beta blockers or calcium channel blockers) and/or rhythm control with class III antiarrhythmics (such as ibutilide or dofetilide). However, atrial flutter is more resistant to correction with such medications than atrial fibrillation.[1] For example, although the class III antiarrhythmic agent ibutilide is an effective treatment for atrial flutter, rates of recurrence after treatment are quite high (70–90%).[1] Additionally, there are some specific considerations particular to treatment of atrial flutter.[citation needed]

Cardioversion

[edit]Atrial flutter is considerably more sensitive to electrical direct current cardioversion than atrial fibrillation, with a shock of only 20 to 50 Joules commonly being enough to cause a return to a normal heart rhythm (sinus rhythm). Exact placement of the pads does not appear important.[16]

Ablation

[edit]Due to the reentrant nature of atrial flutter, it is often possible to ablate the circuit that causes atrial flutter with radiofrequency catheter ablation. Catheter ablation is considered to be a first-line treatment method for many people with typical atrial flutter due to its high rate of success (>90%) and low incidence of complications.[1] This is done in the cardiac electrophysiology lab by causing a ridge of scar tissue in the cavotricuspid isthmus that crosses the path of the circuit that causes atrial flutter. Eliminating conduction through the isthmus prevents reentry, and if successful, prevents the recurrence of the atrial flutter. Atrial fibrillation often occurs (30% within 5 years) after catheter ablation for atrial flutter.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Sawhney, NS; Anousheh, R; Chen, WC; Feld, GK (February 2009). "Diagnosis and management of typical atrial flutter". Cardiology Clinics (Review). 27 (1): 55–67, viii. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2008.09.010. PMID 19111764.

- ^ a b c d Link, MS (October 2012). "Clinical practice. Evaluation and initial treatment of supraventricular tachycardia". New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (15): 1438–48. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1111259. PMID 23050527.

- ^ a b c d Bun, SS; Latcu, DG; Marchlinski, F; Saoudi, N (September 2015). "Atrial flutter: more than just one of a kind". European Heart Journal. 36 (35): 2356–63. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv118. PMID 25838435.

- ^ Vadmann, H; Nielsen, PB; Hjortshøj, SP; Riahi, S; Rasmussen, LH; Lip, GY; Larsen, TB (September 2015). "Atrial flutter and thromboembolic risk: a systematic review". Heart. 101 (18): 1446–55. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307550. PMID 26149627. S2CID 26126493.

- ^ Lewis T, Feil HS, Stroud WD (1920). "Observations upon flutter, fibrillation, II: the nature of auricular flutter". Heart. 7: 191.

- ^ "Atrial Flutter". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Atrial Flutter". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Atrial Flutter". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Vidaillet H, Granada JF, Chyou PH, Maassen K, Ortiz M, Pulido JN, et al. (2002). "A Population-Based Study of Mortality among Patients with Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter". The American Journal of Medicine. 113 (5): 365–70. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01253-6. PMID 12401530.

- ^ Stoddard, M. F. (2000). "Risk of thromboembolism in acute atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter". Echocardiography. 17 (4): 393–405. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8175.2000.tb01155.x. PMID 10979012. S2CID 20652213. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Yow, A. G.; Rajasurya, V.; Sharma, S. (2023). "Sudden Cardiac Death". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. PMID 29939631. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Atrial Flutter". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Surawicz, Borys; Knilans, Timothy K.; Chou, Te-Chuan (2001). Chou's electrocardiography in clinical practice: adult and pediatric. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-8697-4.[page needed]

- ^ "Atrial Flutter: Overview". eMedicine Cardiology. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- ^ Garan, H (April 2008). "Atypical atrial flutter". Heart Rhythm. 5 (4): 618–21. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.10.031. PMID 18325846.

- ^ Kirkland, S; Stiell, I; AlShawabkeh, T; Campbell, S; Dickinson, G; Rowe, BH (July 2014). "The efficacy of pad placement for electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation/flutter: a systematic review". Academic Emergency Medicine. 21 (7): 717–26. doi:10.1111/acem.12407. PMID 25117151.