Tartarus

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

| Greek deities series |

|---|

| Primordial deities |

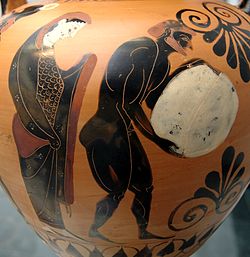

In Greek mythology, Tartarus (/ˈtɑːrtərəs/; Ancient Greek: Τάρταρος, romanized: Tártaros)[1] is the deep abyss that is used as a dungeon of torment and suffering for the wicked and as the prison for the Titans. Tartarus is the place where, according to Plato's Gorgias (c. 400 BC), souls are judged after death and where the wicked received divine punishment. Tartarus appears in early Greek cosmology, such as in Hesiod's Theogony, where the personified Tartarus is described as one of the earliest beings to exist, alongside Chaos and Gaia (Earth).

Greek mythology

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Greek underworld |

|---|

| Residents |

| Geography |

| Prisoners |

| Visitors |

In Greek mythology, Tartarus is both a deity and a place in the underworld.

As a deity

[edit]In the Greek poet Hesiod's Theogony (c. late 8th century BC), Tartarus was the third of the primordial deities, following after Chaos and Gaia (Earth), and preceding Eros,[2] and was the father, by Gaia, of the monster Typhon.[3] According to Hyginus, Tartarus was the offspring of Aether and Gaia.[4]

As a location

[edit]Hesiod asserts that a bronze anvil falling from heaven would fall nine days before it reached the earth. The anvil would take nine more days to fall from earth to Tartarus.[5] In the Iliad (c. 8th century BC), Zeus asserts that Tartarus is "as far beneath Hades as heaven is above earth."[6] Similarly the mythographer Apollodorus, describes Tartarus as "a gloomy place in Hades as far distant from earth as earth is distant from the sky."[7]

While according to Greek mythology the realm of Hades is the place of the dead, Tartarus also has a number of inhabitants. When Cronus came to power as the King of the Titans, he imprisoned the three ancient one-eyed Cyclopes and only the hundred-armed Hecatonchires in Tartarus and set the monster Campe as its guard. Campe was part scorpion and had a ring of animal heads around her waist, snapping at anyone who dared to get near. She also carried a whip to torture the Cyclopes and the hundred-armed ones. Zeus killed Campe and released these imprisoned giants to aid in his conflict with the Titans. The gods of Olympus eventually triumphed. Cronus and many of the other Titans were banished to Tartarus, though Prometheus, Epimetheus, and female Titans such as Metis were spared. Other gods could be sentenced to Tartarus as well. In the Homeric hymn to Hermes, Apollo threatens to throw Hermes into Tartarus. Apollo himself was almost condemned to Tartarus by Zeus for the act of killing the Cyclops. The Hecatonchires became guards of Tartarus's prisoners. Later, when Zeus overcame the monster Typhon, he threw him into "wide Tartarus".[8]

Residents

[edit]Originally, Tartarus was used only to confine dangers to the gods of Olympus and their predecessors. In later mythologies, Tartarus became a space dedicated to the imprisonment and torment of mortals who had sinned against the gods, and each punishment was unique to the condemned. For example:

- King Sisyphus was sent to Tartarus for killing guests and travelers at his castle in violation of his hospitality, seducing his niece, and reporting one of Zeus' sexual conquests by telling the river god Asopus of the whereabouts of his daughter Aegina (who had been taken away by Zeus).[9] But regardless of the impropriety of Zeus' frequent conquests, Sisyphus overstepped his bounds by considering himself a peer of the gods who could rightfully report their indiscretions. When Zeus ordered Thanatos to chain up Sisyphus in Tartarus, Sisyphus tricked Thanatos by asking him how the chains worked and ended up chaining Thanatos; as a result there was no more death. This caused Ares to free Thanatos and turn Sisyphus over to him.[10] Sometime later, Sisyphus had Persephone send him back to the surface to scold his wife for not burying him properly. Sisyphus was forcefully dragged back to Tartarus by Hermes when he refused to go back to the Underworld after that. In Tartarus, Sisyphus was forced forever to try to roll a large boulder to the top of a mountain slope, which, no matter how many times he nearly succeeded in his attempt, would always roll back to the bottom.[11] This constituted the punishment (fitting the crime) of Sisyphus for daring to claim that his cleverness surpassed that of Zeus. Zeus's cunning punishment demonstrated quite the opposite to be the case, condemning Sisyphus to a humiliating eternity of futility and frustration.

- King Tantalus also ended up in Tartarus after he cut up his son Pelops, boiled him, and served him as food when he was invited to dine with the gods.[12] He also stole the ambrosia from the Gods and told his people its secrets.[13] Another story mentioned that he held onto a golden dog forged by Hephaestus and stolen by Tantalus' friend Pandareus. Tantalus held onto the golden dog for safekeeping and later denied to Pandareus that he had it. Tantalus' punishment for his actions (now a proverbial term for "temptation without satisfaction") was to stand in a pool of water beneath a fruit tree with low branches. Whenever he reached for the fruit, the branches raised his intended meal from his grasp. Whenever he bent down to get a drink, the water receded before he could get any. Over his head towered a threatening stone like that of Sisyphus.[14]

- Ixion was the king of the Lapiths, the most ancient tribe of Thessaly. Ixion grew to hate his father-in-law and ended up pushing him onto a bed of coal and wood committing the first kin-related murder. The princes of other lands ordered that Ixion be denied the cleansing of his sin. Zeus took pity on Ixion and invited him to a meal on Olympus. But when Ixion saw Hera, he fell in love with her and did some under-the-table caressing until Zeus signaled him to stop. After finding a place for Ixion to sleep, Zeus created a cloud-clone of Hera named Nephele to test him to see how far he would go to seduce Hera. Ixion made love to her, which resulted in the birth of Centaurus, who mated with some Magnesian mares on Mount Pelion and thus begot the race of Centaurs (who are called the Ixionidae from their descent). Zeus drove Ixion from Mount Olympus and then struck him with a thunderbolt. He was punished by being tied to a winged flaming wheel that was always spinning: first in the sky and then in Tartarus. Only when Orpheus came down to the Underworld to rescue Eurydice did it stop spinning because of the music Orpheus was playing. Ixion's being strapped to the flaming wheel represented his burning lust.

- In some versions, the Danaïdes murdered their husbands and were punished in Tartarus by being forced to carry water in a jug to fill a bath which would thereby wash off their sins. But the jugs were filled with cracks, so the water always leaked out.[15][16]

- The giant Tityos attempted to rape Leto on Hera's orders, but was slain by Apollo and Artemis. As punishment, Tityos was stretched out in Tartarus and tortured by two vultures who fed on his liver. This punishment is extremely similar to that of the Titan Prometheus.

- King Salmoneus was also mentioned to have been imprisoned in Tartarus after passing himself off as Zeus, causing the real Zeus to smite him with a thunderbolt.[17]

- Arke is the sister of Iris who sided with the Titans as their messenger goddess. Zeus removed her wings following the gods' victory over the Titans and she was thrown into Tartarus with the Titans.

- Ocnus was condemned in Tartarus perpetually to weave a rope of straw which, as fast as he weaves it, is just as quickly eaten by a donkey. There is no mention of what he did to deserve this fate.

- When his pregnant daughter Coronis was killed by either Artemis or Apollo, King Phlegyas set fire to the Apollonian temple at Delphi and was killed by Apollo. He was punished in Tartarus by being entombed in a rock and starved in front of an eternal feast as he shouts to the other inhabitants not to despise the gods.

According to Plato (c. 427 BC), Rhadamanthus, Aeacus and Minos were the judges of the dead and chose who went to Tartarus. Rhadamanthus judged Asian souls, Aeacus judged European souls and Minos was the deciding vote and judge of the Greek.[18] Souls regarded as unjust or perjured would go to Tartarus.[18] Those who committed crimes seen as curable would be purified there, while those who committed crimes seen as uncurable would be eternally damned, and demonstrate a warning example for the living.[18] In Gorgias, Plato writes about Socrates telling Callicles, who believes might makes right,[19] that doing injustice to others is worse than suffering injustice, and most uncurable inhabitants of Tartarus were tyrants whose might gave them the opportunity to commit huge crimes.[18] Archelaus I of Macedon is mentioned as a possible example of this, while Thersites is said to be curable, because of his lack of might.[18] According to Plato's Phaedo, the uncurable consisted of temple robbers and murderers, while sons who killed one of their parents during a status of rage but regretted this their whole life long, and involuntary manslaughterers, would be taken out of Tartarus after one year, so they could ask their victims for forgiveness.[20] If they should be forgiven, they were liberated, but if not, would go back and stay there until they were finally pardoned.[20] In the Republic, Plato mentions the Myth of Er, who is said to have been a fallen soldier who resurrected from the dead, and saw their realm.[21] According to this, the length of a punishment an adult receives for each crime in Tartarus, who is responsible for a lot of deaths, betrayed states or armies and sold them into slavery or had been involved in similar misdeeds, corresponds to ten times out of a hundred earthly years (while good deeds would be rewarded in equal measure).[21]

There were a number of entrances to Tartarus in Greek mythology. One was in Aornum.[22]

Roman mythology

[edit]In Roman mythology, sinners (as defined by the Roman societal and cultural norms of their time) are sent to Tartarus for punishment after death. Virgil describes Tartarus in great detail in the Aeneid, Book VI. He described it as expansive. It is surrounded by three perimeter walls, beyond which flows a flaming river named the Phlegethon. Drinking from the Phlegethon will not kill a mortal and it will heal while causing great pain. To further prevent escape, a hydra with fifty black, gaping jaws sits atop a gate that screeches when opened. They are flanked by adamantine columns, a substance that, like diamond, was believed to be so hard that nothing can cut through it.[citation needed]

Inside the walls of Tartarus sits a wide-walled castle with a tall, iron turret. Tisiphone, one of the Erinyes, who represents vengeance, stands sleepless guard at the top of the turret lashing her whip. Roman mythology describes a pit inside extending down into the earth twice as far as the distance from the lands of the living to Olympus. The twin sons of the Titan Aloeus were said to be imprisoned at the bottom of this pit.[citation needed]

Biblical pseudepigrapha

[edit]Tartarus occurs in the Septuagint translation of Job (40:20 and 41:24) into Koine Greek, and in Hellenistic Jewish literature from the Greek text of the Book of Enoch, dated to 400–200 BC. This states that God placed the archangel Uriel "in charge of the world and of Tartarus" (20:2). Tartarus is generally understood to be the place where 200 fallen Watchers (angels) are imprisoned.[23]

Reference to the watchers of the book of Enoch is also observed in Jude 1:6-7 where scripture describes Angels being bound by chains under everlasting darkness, and 2 Peter 2:4 which further describes fallen angels committed to chains in Tartarus.

In Hypostasis of the Archons (also translated 'Reality of the Rulers'), an apocryphal gnostic treatise dated before 350 AD, Tartarus makes a brief appearance when Zōē (life), the daughter of Sophia (wisdom) casts Ialdabaōth (demiurge) down to the bottom of the abyss of Tartarus.[24]

In The Book of Thomas, Tartaros is claimed by Jesus to be the place where those who hear the word of Judas Thomas and "turn away or sneer" are to be sent. These damned will be handed over to the angel or power Tartarouchos.[25]

New Testament

[edit]In the New Testament, the noun Tartarus does not occur but tartaroō (ταρταρόω, "throw to Tartarus"), a shortened form of the classical Greek verb kata-tartaroō ("throw down to Tartarus"), does appear in 2 Peter 2:4. Liddell–Scott provides other sources for the shortened form of this verb, including Acusilaus (5th century BC), Joannes Laurentius Lydus (4th century AD) and the Scholiast on Aeschylus' Eumenides, who cites Pindar relating how the earth tried to tartaro "cast down" Apollo after he overcame the Python.[26] In classical texts, the longer form kata-tartaroo is often related to the throwing of the Titans down to Tartarus.[27]

The English Standard Version is one of several English versions that gives the Greek reading Tartarus as a footnote:

For if God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell(a) and committed them to chains(b) of gloomy darkness to be kept until the judgment;

— 2 Peter 2:4 (Footnote a: Greek Tartarus)

Adam Clarke reasoned that Peter's use of language relating to the Titans was an indication that the ancient Greeks had heard of a Biblical punishment of fallen angels.[28] Some Evangelical Christian commentaries distinguish Tartarus as a place for wicked angels and Gehenna as a place for wicked humans on the basis of this verse.[29] Other Evangelical commentaries, in reconciling that some fallen angels are chained in Tartarus, yet some not, attempt to distinguish between one type of fallen angel and another.[30]

See also

[edit]- Greek mythology in popular culture

- Erebus

- Charon

- Lake of fire

- Duat

- Hell

- Orcus

- Sheol

- The Golden Bough (mythology)

- The tartaruchi of the non-canonical Apocalypse of Paul.

- Tzoah Rotachat

References

[edit]- ^ The word is of uncertain origin. (Harper, Douglas. "Tartarus". Online Etymology Dictionary.)

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 116–119; Gantz p. 3; Hard, p. 23.

- ^ Hesiod. Theogony 820–822; Tripp, s.v. Tartarus; Grimal, s.v. Tartarus.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae Preface; Smith, s.v. Tartarus.

- ^ Hesiod. Theogony, 720–725

- ^ Homer. Iliad, 8.17

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.1.2.

- ^ Hesiod. Theogony, 868

- ^ Hamilton, Edith. "Brief Myths." Mythology.

- ^ "Ancient Greeks: Is death necessary and can death actually harm us?". Mlahanas.de. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Homer. Odyssey, 11.593–600

- ^ Pindar. Olympian Odes, 1.24–38

- ^ Pindar. Olympian Odes, 1.60 ff

- ^ Homer. Odyssey, 11.582-92; Tantalus' transgressions are not mentioned; they must already have been well known to Homer's late-8th-century hearers.

- ^ The Danish government's third world aid agency's name was changed from DANAID to DANIDA in the last minute when this unfortunate connotation was discovered.

- ^ Tripp, Edward (2007). The Meridian handbook of classical mythology. Edward Tripp. New York, N.Y.: Plume. ISBN 978-0-452-00927-1. OCLC 123131145.

- ^ Virgil. Aeneid, 6.585–594

- ^ a b c d e Plato, Gorgias, 523a-527e.

- ^ Plato, Gorgias, 482d-486e.

- ^ a b Platon, Phaidon, ed. and transl. by Rudolf Kassner, Jena 1906, S. 105–106.

- ^ a b Plato, Der Staat, ed. and transl. by August Horneffer, Leipzig 1908, p. 348–351.

- ^ The Greek Myths (Volume 1) by Robert Graves (1990), page 112: "... He used the passage which opens at Aornum in Thesprotis and, on his arrival, not only charmed the ferryman Charon..."

- ^ Kelley Coblentz Bautch A Study of the Geography of 1 Enoch 17–19: "no One Has Seen what I Have Seen" p134

- ^ Bentley Layton The Gnostic Scriptures: "Reality of the Rulers" 95:5 p.74

- ^ John D. Turner The Nag Hammadi Scriptures - The Revised and Updated Translation of Sacred Gnostic Texts Complete in One Volume: Introduction to "The Book of Thomas" p.235

- ^ A. cast into Tartarus or hell, Acus.8 J., 2 Ep.Pet.2.4, Lyd.Mens.4.158 (Pass.), Sch.T Il.14.296. Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by. Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

- ^ Apollodorus of Athens, in Didymus' Scholia on Homer; Plutarch Concerning rivers

- ^ Clarke Commentary "The ancient Greeks appear to have received, by tradition, an account of the punishment of the 'fallen angels,' and of bad men after death; and their poets did, in conformity I presume with that account, make Tartarus the place where the giants who rebelled against Jupiter, and the souls of the wicked, were confined. 'Here,' saith Hesiod, Theogon., lin. 720, 1, 'the rebellious Titans were bound in penal chains.'"

- ^ Paul V. Harrison, Robert E. Picirilli James, 1, 2 Peter, Jude Randall House Commentaries 1992 p267 "We do not need to say, then, that Peter was reflecting or approving the Book of Enoch (20:2) when it names Tartarus as a place for wicked angels in distinction from Gehenna as the place for wicked humans."

- ^ Vince Garcia The Resurrection Life Study Bible 2007 p412 "If so, we have a problem: Satan and his angels are not locked up in Tartarus! Satan and his angels were alive and active in the time of Christ, and still are today! Yet Peter specifically (2 Peter 2:4) states that at least one group of angelic beings have literally been cast down to Tartarus and bound in chains until the Last Judgment. So if Satan and his angels are not currently bound in Tartarus—who is? The answer goes back~again~to the angels who interbred with humans. So then— is it impossible that Azazel is somehow another name for Satan? There may be a chance he is, but there is no way of knowing for sure. ..."

Bibliography

[edit]- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Grimal, Pierre, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 978-0-631-20102-1.

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360. Google Books.

- Hesiod, Theogony from The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PhD in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

- Hyginus, Fabulae from The Myths of Hyginus translated and edited by Mary Grant. University of Kansas Publications in Humanistic Studies. Online version at the Topos Text Project.

- Pindar, Odes translated by Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pindar, The Odes of Pindar including the Principal Fragments with an Introduction and an English Translation by Sir John Sandys, Litt.D., FBA. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1937. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Publius Vergilius Maro, Aeneid. Theodore C. Williams. trans. Boston. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1910. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Publius Vergilius Maro, Bucolics, Aeneid, and Georgics. J. B. Greenough. Boston. Ginn & Co. 1900. Latin text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Smith, William, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Tripp, Edward, Crowell's Handbook of Classical Mythology, Thomas Y. Crowell Co; First edition (June 1970). ISBN 069022608X.