Prekmurje Slovene

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Prekmurje Slovene | |

|---|---|

| prekmursko narečje, prekmurščina, prekmürščina, prekmörščina, panonska slovenščina | |

| Native to | Slovenia, Hungary and emigrant groups in various countries |

| Ethnicity | notably Hungarian Slovenes |

Native speakers | (undated figure of 110,000)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | prek1239 |

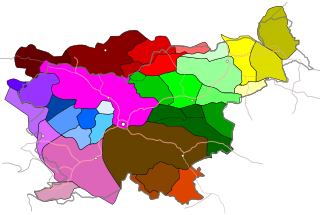

Map of Slovenian dialects. Prekmurje Slovene is in dark yellow at the top right. | |

Prekmurje Slovene, also known as the Prekmurje dialect, East Slovene, or Wendish (Slovene: prekmurščina, prekmursko narečje, Hungarian: vend nyelv, muravidéki nyelv, Prekmurje Slovene: prekmürski jezik, prekmürščina, prekmörščina, prekmörski jezik, panonska slovenščina), is the language of Prekmurje in Eastern Slovenia, variety of Slovene language,[2] part of the Pannonian dialect group.[3] It is used in private communication, liturgy, publications by authors from Prekmurje.[4][5] and in media of television, radio and newspapers.[6][7][8][9] It is spoken in the Prekmurje region of Slovenia and by the Hungarian Slovenes in Vas County in western Hungary. It is closely related to other Slovene dialects in neighboring Slovene Styria, as well as to Kajkavian with which it retains a considerable degree of mutual intelligibility and forms a dialect continuum with other South Slavic languages.

Range

[edit]The Prekmurje Slovene is spoken by approximately 110,000 speakers worldwide.[1] 80,000 in Prekmurje, 20,000 dispersed in Slovenia (especially Maribor and Ljubljana) and 10,000 in other countries. In Hungary it is used by the Slovene-speaking minority in Vas County in and around the town of Szentgotthárd. Other speakers of the dialect live in other Hungarian towns, particularly Budapest, Szombathely, Bakony, and Mosonmagyaróvár. The dialect was also spoken in Somogy (especially in the village of Tarany), but it has nearly disappeared in the last two centuries. There are some speakers in Austria, Germany, the United States, and Argentina.

Status

[edit]Prekmurje Slovene has a defined territory and body of literature, and it is one of the few Slovene dialects in Slovenia that is still spoken by all strata of the local population.[10] Some speakers have claimed that it is a separate language. Prominent writers in Prekmurje Slovene, such as Miklós Küzmics,[10] István Küzmics, Ágoston Pável, József Klekl Senior,[11] and József Szakovics, have claimed that it is a language, not simply a dialect. Evald Flisar, a writer, poet, and playwright from Prekmurje (Goričko), states that people from Prekmurje "talk in our own language."[10] It also had a written standard and literary tradition, both of which were largely neglected after World War II. There were attempts to publish in it more widely in the 1990s, primarily in Hungary,[12] and there has been a revival of literature in Prekmurje Slovene since the late 1990s.

Others consider Prekmurje Slovene a regional language, without denying that it is part of Slovene.[clarification needed][who?] The linguist Janko Dular has characterized Prekmurje Slovene as a "local standard language" for historical reasons,[13] as has the Prekmurje writer Feri Lainšček. However, Prekmurje Slovene is not recognized as a language by Slovenia or Hungary, nor does it enjoy any legal protection under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, although in 2016 the General Maister Society (Društvo General Maister) proposed that primary schools offer education in the Prekmurje Slovene[14][15] and some regional politicians and intellectuals advocate Prekmurje Slovene.[16]

Together with Resian, Prekmurje Slovene is the only Slovene dialect with a literary standard that has had a different historical development from the rest of Slovene ethnic territory. For centuries, it was used as a language of religious education, as well as in the press and mass.[17] The historical Hungarian name for the Slovenes living within the borders of the Kingdom of Hungary (as well as for the Slovenians in general) was Vendek, or the Wends. In the 18th and 19th centuries Prekmurje authors used to designate this language variety as sztári szlovenszki jezik 'old Slovene'. Both then and now, it is also referred to as the "Slovene language between the Mura and Raba" (Slovenščina med Muro in Rabo; Slovenski jezik med Mürov i Rábov).

Prekmurje Slovene is widely used in the regional media (Murski Val Radio, Porabje, Slovenski utrinki), films,[18] literature. The younger generation also write SMS messages and web comments in their local tongue. In the Prekmurje and Hungary a few streets, shops, hotels, etc. have Prekmurje Slovene names.[19][20] In the 2012 protests in Slovenia in Murska Sobota the protesters use Prekmurje Slovene banners.[21] It is the liturgical language in the Lutheran and Pentecostal churches, and in the Catholic Church of Hungarian Slovenes. Marko Jesenšek, a professor at the University of Maribor, states that the functionality of Prekmurje Slovene is limited, but "it lives on in poetry and journalism."[22]

Linguistic features

[edit]Prekmurje Slovene is part of the Pannonian dialect group (Slovene: panonska narečna skupina), also known as the eastern Slovene dialect group (vzhodnoslovenska narečna skupina). Prekmurje Slovene shares many common features with the dialects of Haloze, Slovenske Gorice, and Prlekija, with which it is completely mutually intelligible. It is also closely related to the Kajkavian dialect of Croatian, although mutual comprehension is difficult. Prekmurje Slovene, especially its more traditional version spoken by the Hungarian Slovenes, is not readily understood by speakers from central and western Slovenia, whereas speakers from eastern Slovenia (Lower Styria) have much less difficulty understanding it. The early 20th-century philologist Ágoston Pável stated that Prekmurje Slovene in fact it is a major, independent dialect of Slovene, from which it differs mostly in the relationships of stress, in intonation, in the softening of consonant and—as a result of the lack of lunguistic reform—in the striking dearth of modern vocabulary[23] and that it preserves many older features from Proto-Slavic language.

Orthography

[edit]Historically, Prekmurje Slovene was not written with the Bohorič alphabet used by Slovenes in Inner Austria, but with a Hungarian-based orthography. János Murkovics's textbook (1871) was the first book to use Gaj's Latin Alphabet.

Before 1914: Aa, Áá, Bb, Cc, Cscs, Dd, Ee, Éé, Êê, Ff, Gg, Gygy, Hh, Ii, Jj, Kk, Ll, Lyly, Mm, Nn, Nyny, Oo, Ôô, Öö, Őő, Pp, Rr, Szsz, Ss, Tt, Uu, Üü, Űű, Vv, Zz, Zszs.

After 1914: Aa, Áá, Bb, Cc, Čč, Dd, Ee, Éé, Êê, Ff, Gg, Gjgj, Hh, Ii, Jj, Kk, Ll, Ljlj, Mm, Nn, Njnj, Oo, Ôô, Öö, Pp, Rr, Ss, Šš, Tt, Uu, Üü, Vv, Zz, Žž.

Phonology

[edit]Vowel ö occurs only in a few words as a variant of closed e or ö.[24] It has plain a in long stressed syllables and rounded a in short stressed and unstressed syllables in Hill country (Goričko) and Lowland (Ravensko) dialect.[24] The relationship is reversed in the Lower Lowland (Dolinsko) dialect, where the long stressed a is rounded.[24]

Long vowels and most are diphtongs occur only stressed in syllables. If the stress shiftsm the vowel loses its lenght and the diphtong usually loses its glide, for ex.: Nom. Boug; Gen. Bogá.[24]

Diphtongs

[edit]Diphtong ej (ei) is a short, closed e by a shorter, less fully articulated i. For ex. dejte (child), bejžati (run), pejnezi (money), mlejko (milk), bejli (white).[25]

Diphtong ou consists of a short o and a short, less fully articulated u. For ex. rouka (hand), nouga (foot), goloub (dove), rour (chimney), gospoud (lord).

Prekmurian Slovene is very rich in diphtongs ej and ou.[25] The diphtongs found in various Slovene dialects, but phonetically is different from the diphtongs of Prekmurian Slovene. The ou and ej diphtongs was represented in the old Prekmurian literary language ortographically by separate signs ê and ô but only in the books and newspapers of the Lutheran Slovenes.[26]

The diphtong ou in northern Goričko subdialects (mostly near river Raba) and in the settlements along the Hungarian-Slovene border is reducated to the au. The Ravensko dialect and some Goričko subdialect have diphtongs üj or öj.[27]

Diphtongs in open syllables, if they occur in polysyllabic words, are broken up into their components,[28] for ex. Nom. sou (salt), Gen. soli; Nom. krau (king), Gen. krala.

Vowel alternations

[edit]a>e

Unstressed a and a in a diphtong with i or j often sounds like open e.[29] This system is typical mostly in the lower Lowland (Dolinsko) dialect, for ex. eli (or) (Ravensko, Goričko, Standard Slovene: ali), nezaj (back) (Ravensko, Goričko, Standard Slovene: nazaj), dele (forward) (Ravensko, Goričko: dale, Standard Slovene: dalje).

o>i

This is a sporadic dissimilation and assimilation. For ex. visiki (high, Standard Slovene visok).[29]

o>e

In inflected forms a soft consonant (c, č, š, ž, j) is usually followed by o instead of the e in Standard Slovene.[30] For ex.: z noužicon Standard Slovene z nožem (with knife), s konjon Standard Slovene s konjem (with horse). In neuter nominative singular and accusative is also o heard instead of the e: For ex. mojo delo, našo delo, Standard Slovene moje delo, naše delo (my work, our work). Innovative e is heard only in the eastern subdialects of the Dolinsko dialect, mostly along the Slovene-Croatian border (near the Međimurje).

o>u

The diactric ŭ refere to the non-frontedness of the vowel.[30] For ex. un, una Standard Slovene on, ona (he, she). The Dolinsko dialect have has even more diactric u, for ex. kunj (horse) (Ravensko, Goričko, Standard Slovene: konj), Marku (Marc) (Ravensko, Goričko, Standard Slovene Marko).

a>o

For ex. zakoj (why) (Standard Slovene zakaj).

u>ü

The historical u is pronounced almost without exception as ü and it is also spelled this way.[30] For ex. küp (mound) (Standard Slovene kup), küpiti (purchase) (Standard Slovene kupiti), düša (soul) (Standard Slovene duša), lüknja (slit) (Standard Slovene luknja), brüsiti (facet) (Standard Slovene brusiti).

In words starting wutg a v there are mixed forms,[28] while in the Standard Slovene remains the u, for ex. vüjo (ear) (Standard Slovene uho), vujti (escapes) (Standard Slovene uiti).

The u derived from earlier ol preceding a consonant does not turn into ü,[28] for ex. pun (full) (Standard Slovene poln), dugi (long) (Standard Slovene dolg), vuna (wool) (Standard Slovene volna), vuk (wolf) (Standard Slovene volk).

Consonant alternations

[edit]Z preceding nj often sound like ž, for ex. ž njin (with him) (Standard Slovene z njim).

k>c

For ex. tenko, natenci (thin, thinly) (Standard Slovene tanko, natanko).[31] This type of alternations was even more frequent in the old Prekmurian Slovene,[31] for ex. vuk, vucke, vuci (wolf, wolfs) (Standard Slovene volk, volki, Croatian vuk, vuci). Today it is preserved in the speech of older people in Goričko and the subdialect of Hungarian Slovenes.

m>n

Word final m in Prekmurian Slovene almost always sounds like n[32] (just like in other Pannonian Slovene dialects[33][34] or in the Chakavian[35]). For ex. znan (I know) (Standard Slovene znam), man (I have) (Standard Slovene imam), tan (there) (Standard Slovene tam), vüzen (Easter) (Standard Slovene vuzem[36] z zlaton (with gold) (Standard Slovene z zlatom), ran (building) (Standard Slovene hram). Exceptions: grm (bush), doum (home), tram (strut) etc.

The change of m>n can also occur in middle position, preceding consonants,[32] for ex.: Nom. vüzen, Gen. vüzma.

nj>n

The n has developed from an nj in word-final position or medial position,[37] for ex. ogen (fire) (Standard Slovene ogenj), kniga (book) (Standard Slovene knjiga). In declined forms nj return,[37] for ex. ognja (Genitive).

lj>l

The hard lj (ł) has totally disappeared from Prekmurian Slovene,[37] for ex.: klüč (key) (Standard Slovene ključ), lübiti, lübezen (love) (Standard Slovene ljubiti, ljubezen), grable (rake) (Standard Slovene grablje).

h>j or ∅

In certain regions and in certain positions it is still present the h.

- in word initial position preceding a vowel or syllable forming r its usage is ambigous and regionally variable.[37] For ex. hüdi, üdi (evil) (Standard Slovene hud). In noun iža (house) (Standard Slovene hiša) in every Prekmurian dialect is missing the h

- in medial position, between vowels h is present, a j has replaced it,[37] for ex. küjati (cook) (Standard Slovene kuhati)

- h usually disappears in word position followed by consonants and in medial position preceded by consonants,[38] for ex. lad (cold) (Standard Slovene hlad), sprneti (decay) (Standard Slovene trohneti)

- the syllable-final h in word-medial position followed by consonants usually turns into j, which merge with the preceding vowel to form a diphtong,[38] for ex. lejko (perhaps, easily) (Standard Slovene lahko)

- in word-final position, preceded by a vowel, it either changes into j,[38] for ex. grej (sin) (Standard Slovene greh), krüj (bread) (Standard Slovene kruh).

Exceptions shajati (to make do on something), zahtejvati (demand) etc.

bn>vn

For ex. drouvno (tiny) (Standard Slovene drobno).

p>f

For ex. ftic, ftič, ftica (bird) (Standard Slovene ptic, ptič, ptica).

j>d

For ex. žeden (thirsty) (Standard Slovene žejen).

hč>šč

For ex. nišče (nobody) (Standard Slovene nihče).

kt>št

For ex. što (who) (Standard Slovene: kdo).

ljš>kš

For ex. boukši (better, right) (Standard Slovene boljši).

dn (dnj)>gn (gnj)

For ex. gnes, gnjes (today) (Standard Slovene danes). Nom. škegen (barn), Gen. škegnja.

t>k

Manly preceding an l.[39]

- word-initially, for ex. kmica (darkness), klačiti (to tread) (Standard Slovene tlačiti), kusti (thick, fat) (Standard Slovene tolst)

- in word medial position, for ex. mekla (broom) (Standard Slovene metla)

- in word-final position soldak (soldier).

Morphology

[edit]Also in Prekmurian Slovene can be nouns masculine, feminine or neuter.[40] Nouns, adjectives and pronouns have three numbers: singular, dual and plural,[41] just like in the Standard Slovene.[42]

Feminine

[edit]Feminine nouns ending in a.[43]

| Declension patterns of feminine nouns ending in a (Prekmurian Slovene) | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -a | -i/ej | -e |

| Gen. | -e | -∅/ej | -∅ |

| Dat. | -i/ej | -ama | -an |

| Ac. | -o/ou | -i/ej | -e |

| Loc. | -i/ej | -ama/aj | -aj |

| Inst. | -of(v)/-ouf(v) | -ama | -ami |

| Declension patterns of feminine nouns ending in a (Standard Slovene)[44] | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -a | -i | -e |

| Gen. | -e | -∅ | -∅ |

| Dat. | -i | -ama | -am |

| Ac. | -o | -i | -e |

| Loc. | -i | -ah | -ah |

| Inst. | -o | -ama | -ami |

Feminine nouns ending in consonant.[45]

| Declension patterns of feminine nouns ending in a (Prekmurian Slovene) | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -∅ | -i/ej | -i |

| Gen. | -i | -i/ej | -i |

| Dat. | -i | -ama | -an |

| Ac. | -∅ | -i/ej | -i |

| Loc. | -i | -ama/aj | -aj |

| Inst. | -jof(v)/-of(v) | -ama | -ami |

| Declension patterns of feminine nouns ending in a (Standard Slovene)[46] | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -∅ | -i | -i |

| Gen. | -i | -i | -i |

| Dat. | -i | -ema | -em |

| Ac. | -∅ | -i | -i |

| Loc. | -i | -eh/ih | -eh/ih |

| Inst. | -o | -ema | -mi |

Declension of feminine adjective.[47]

| Declension patterns of feminine adjectives (Prekmurian Slovene) | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -a | -ivi/evi | -e |

| Gen. | -e | -ivi(j)/evi(j) | -i(j) |

| Dat. | -oj | -ima | -in |

| Ac. | -o | -ivi/evi | -e |

| Loc. | -oj | -ima/ivaj/evaj | -i(j) |

| Inst. | -of(v) | -ima/ivima/evima | -imi |

| Declension patterns of feminine adjectives (Standard Slovene)[48] | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -a | -i | -e |

| Gen. | -e | -ih | -ih |

| Dat. | -i | -ima | -im |

| Ac. | -o | -i | -e |

| Loc. | -i | -ih | -ih |

| Inst. | -o | -ima | -imi |

Masculine

[edit]Masculine nons ending in a consonant.[49] The singular accusative of masculine nouns designating animate things is the same as their genitive form. The singular accusative of nouns designatinginanimate things is the same as their nominative.[49]

| Declension patterns of masculine nouns ending in consonant (Prekmurian Slovene) | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -∅ | -a | -i |

| Gen. | -a | -a/of(v) | -of(v) |

| Dat. | -i | -oma | -on |

| Ac. | -∅/a | -a | -e |

| Loc. | -i | -oma/aj | -aj/i |

| Inst. | -on | -oma | -ami |

| Declension patterns of masculine nouns ending in consonant (Standard Slovene)[50] | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -∅ | -a | -i |

| Gen. | -∅/a | -ov | -ov |

| Dat. | -u | -oma | -om/-em |

| Ac. | -∅/a | -a | -e |

| Loc. | -u | -ih | -ih |

| Inst. | -om/-em | -oma | -i |

Masculines nouns ending in a.[51]

| Declension patterns of feminine nouns ending in a (Prekmurian Slovene) | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -a | -a | -e/i |

| Gen. | -o/e | -of(v)/a | -∅/of(v) |

| Dat. | -i | -oma | -on |

| Ac. | -o | -a/i | -e |

| Loc. | -i | -oma/aj | -aj |

| Inst. | -of(v) | -oma | -ami/i |

| Declension patterns of feminine nouns ending in a (Standard Slovene)[52] | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -a | -i | -e |

| Gen. | -e | -∅ | -∅ |

| Dat. | -i | -ama | -am |

| Ac. | -o | -i | -e |

| Loc. | -i | -ah | -ah |

| Inst. | -o | -ama | -ami |

Declension of masculine adjective.[47]

| Declension patterns of masculine adjectives (Prekmurian Slovene)[53] | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -i | -iva/eva | -i |

| Gen. | -oga | -iva/ivi(j)/eva/evi(j) | -i(j) |

| Dat. | -omi | -ima | -in |

| Ac. | -i/oga | -iva/eva | -e |

| Loc. | -on | -ima/ivaj/evaj/i(j) | -i(j) |

| Inst. | -in | -ima/ivima/evima | -imi |

| Declension patterns of masculine adjectives (Standard Slovene) | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -∅ | -a | -i |

| Gen. | -∅/ega | -ih | -ih |

| Dat. | -emu | -ima | -im |

| Ac. | -∅/ega | -a | -e |

| Loc. | -em | -ih | -ih |

| Inst. | -im | -ima | -imi |

Neuter

[edit]Neuter nouns ending in o and e.[54]

| Declension patterns of neuter nouns ending in o or e (Prekmurian Slovene) | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -o/e | -i | -a |

| Gen. | -a | -i/∅ | -∅ |

| Dat. | -i | -oma | -an |

| Ac. | -o/e | -i | -a |

| Loc. | -i | -oma/aj | -aj/ami/i |

| Inst. | -on | -oma | -ami/i |

In the declension of nouns for ex tejlo (body, St. Slov.: telo) or drejvo (three, St. Slov.: drevo) are not lengthened as in the Standard Slovene with the syllable –es (Prekmurian: Nom. tejlo, drejvo Gen. tejla, drejva; Standard Slovene: Nom. telo, drevo Gen. telesa, drevesa).[55]

| Declension patterns of masculine nouns ending in e (Standard Slovene)[56] | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -e | -i | -a |

| Gen. | -a | -∅ | -∅ |

| Dat. | -u | -ema | -em |

| Ac. | -e | -i | -a |

| Loc. | -u | -ih | -ih |

| Inst. | -em | -ima | -i |

| Declension patterns of masculine nouns ending in o (Standard Slovene)[57] | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -o | -i | -a |

| Gen. | -a | -∅ | -∅ |

| Dat. | -u | -oma | -om |

| Ac. | -o | -i | -a |

| Loc. | -u | -ih | -ih |

| Inst. | -om | -oma | -i |

Declension of neuter adjective.[47]

| Declension patterns of masculine adjectives (Prekmurian Slovene) | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -o | -ivi/evi | -a |

| Gen. | -oga | -ivi(j)/evi(j)/i(j) | -i(j) |

| Dat. | -omi | -ima/ivima/evima | -in |

| Ac. | -o | -ivi/evi | -a |

| Loc. | -on | -ima/ivima/evima/i(j) | -i(j) |

| Inst. | -in | -ima/ivima/evima | -imi |

| Declension patterns of neuter adjectives (Standard Slovene)[48] | |||

| Grammatical case\Number | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -o/e | -i | -a |

| Gen. | -ega | -ih | -ih |

| Dat. | -emu | -ima | -im |

| Ac. | -o/e | -i | -a |

| Loc. | -em | -ih | -ih |

| Inst. | -im | -ima | -imi |

Personal pronouns

[edit]Singular

[edit]| Nom. | ges/jes (Masc.Fem.) | ti(j) (Masc.Fem.) | un (Masc.) | una (Fem.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen. | mene(j) me |

tebe(j) te |

njega ga |

nje je |

| Dat. | meni mi |

tebi ti |

njemi | njej/njoj ji |

| Ac. | mene(j) me |

tebe(j) te |

njega ga |

njou jo |

| Loc. | meni | tebi | njen | njej/njoj |

| Inst | menof(v)/meuf | tebof(v)/teuf | njin | njouf(v) |

| Nom. | jaz (Masc.Fem.Neut.) | ti (Masc.Fem.Neut) | on (Masc.) | ona (Fem.) | ono (Neut.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen. | mene me |

tebe te |

njega ga |

nje je |

njega ga |

| Dat. | meni mi |

tebi ti |

njemu mu |

njej/nji ji |

njemu mu |

| Ac. | mene me -me |

tebe te -te |

njega ga -(e)nj |

njo jo -njo |

njega/ono ga -(e)nj |

| Loc. | pri meni | pri tebi | pri njem | pri njej/nji | pri njem |

| Inst. | z mano/menoj | s tabo/teboj | z njim | z njo | z njim |

Dual

[edit]| Nom. | müva (Masc.), müve (Fem.) | vüva (Masc.), vüve (Fem.) | njüva/njiva/oneva (Masc), njüve/njive (Fem.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gen. | naj(a) | vaj(a) | njiva(Masc), njivi (Fem.) |

| Dat. | nama | vama | njima |

| Ac. | naj(a) | vaj(a) | njiva(Masc), njivi (Fem.) |

| Loc. | nama | vama | njima |

| Inst. | nama | vama | njima |

| Nom. | midva (Masc.), medve (Fem.Neut.) | vidva (Masc.), vedve (Fem.Neut.) | onadva (Masc.), onidve (Fem.Neut.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gen. | naju | vaju | njiju |

| Dat. | nama | vama | njima jima |

| Ac. | naju | vaju | njiju ju -nju |

| Loc. | naju | vaju | njiju |

| Inst. | nama | vama | njima |

Plural

[edit]| Nom. | mi (Masc.Fem.) | vi (Masc.Fem.) | uni (Masc.), une (Fem.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gen. | nas | vas | njih/nji jih/je |

| Dat. | nan | van | njin jin |

| Ac. | nas | vas | njih/nje jih je |

| Loc. | nas/nan | vas/van | njij |

| Inst. | nami | vami | njimi |

| Nom. | mi (Masc.), me (Fem.Neut.) | vi (Masc.), ve (Fem.Neut.) | oni (Masc.), one (Fem.), ona (Neut.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gen. | nas | vas | njih jih |

| Dat. | nam | vam | njim jim |

| Ac. | nas | vas | njih/nje jih -nje |

| Loc. | nas | vas | njih |

| Inst. | nami | vami | njimi |

Reflexive pronoun

[edit]| Nom. | — |

|---|---|

| Gen. | sebe(j) se |

| Dat. | sebi si |

| Ac. | sebe(j) se |

| Loc. | sebi/sebej |

| Inst. | sebof(v)/seuf |

| Nom. | — |

|---|---|

| Gen. | sebe se |

| Dat. | sebi si |

| Ac. | sebe se -se |

| Loc. | sebi |

| Inst. | sabo/seboj |

Numerals

[edit]The names for numerals in Prekmurian Slovene are formed in a similar way to that found in the Standard Slovene or other Slavic languages.[65][66] The again, the old way of two-digit numbers was preserved. Ten comes first, followed by a one-digit number. They don't need a conjunction. In Standard Slovene the formation of numerals from 21 to 99, in which the unit is placed in front of the decade ("four-and-twenty"), as in German language.

| Prekmurian Slovene | Standard Slovene | Number |

|---|---|---|

| štirideset eden | enainštirideset | 41 |

| štirideset dva | dvainštirideset | 42 |

| štirideset tri(j) | triinštirideset | 43 |

| štirideset štiri | štiriinštirideset | 44 |

Verb

[edit]Verb stems in Prekmurian Slovene is most frequently üvati or avati, more rarely ovati[67] (stem ovati is most frequently in Standard Slovene). In the conjugation suffixes change is also dissimilar in Prekmurian and Slovene. For ex. Prekm. nategüvati, obrezavati, conj. nategüvlen/nategüjen, obrezavlen, Stand. Slov. nategovati, obrezovati, conj. nategujem, obrezujem.

In Goričko dialect and some western subdialects of Ravensko is the infinitive stem with the suffix -niti (zdigniti),[68] just like in the Standard Slovene (dvigniti), infrequently -nouti (Prekm. obrnouti, Stand. Slov. obrniti). In the Dolinsko dialect and other Ravensko subdialects the infinitive stem with the suffix -noti (zdignoti)[68], just like in Croatian (and Kajkavian).

Present tense

[edit]| Singular | lübin | lübiš | lübi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dual | lübiva | lübita | lübita |

| Plural | lübimo | lübite | lübijo |

| Singular | ljubim | ljubiš | ljubi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dual | ljubiva | ljubita | ljubita |

| Plural | ljubimo | ljubite | ljubijo |

Past tense

[edit]| Singular | san/sen lübo(Masc.) lübila(Fem.) |

si lübo(Masc.) lübila(Fem.) |

je lübo(Masc.) lübila(Fem.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dual | sva lübila(Masc.) lübili(Fem.) |

sta lübila(Masc.) lübili(Fem.) |

sta lübila(Masc.) lübili(Fem.) |

| Plural | smo lübili(Masc.) lübile(Fem.) |

ste lübili(Masc.) lübile(Fem.) |

so lübili(Masc.) lübile(Fem.) |

| Singular | sem ljubil(Masc.) ljubila(Fem.) |

si ljubil(Masc.) ljubila(Fem.) |

je ljubil(Masc.) ljubila(Fem.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dual | sva ljubila(Masc.) ljubili(Fem.) |

sta ljubila(Masc.) ljubili(Fem.) |

sta ljubila(Masc.) ljubili(Fem.) |

| Plural | smo ljubili(Masc.) ljubile(Fem.) |

ste ljubili(Masc.) ljubile(Fem.) |

so ljubili(Masc.) ljubile(Fem.) |

Future tense

[edit]| Singular | mo lübo(Masc.) lübila(Fem.) |

boš lübo(Masc.) lübila(Fem.) |

de lübo(Masc.) lübila(Fem.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dual | va lübila(Masc.) lübili(Fem.) |

ta lübila(Masc.) lübili(Fem.) |

ta lübila(Masc.) lübili(Fem.) |

| Plural | mo lübili(Masc.) lübile(Fem.) |

te lübili(Masc.) lübile(Fem.) |

do lübili(Masc.) lübile(Fem.) |

| Singular | bom ljubil(Masc.) ljubila(Fem.) |

boš ljubil(Masc.) ljubila(Fem.) |

bo ljubil(Masc.) ljubila(Fem.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dual | bova ljubila(Masc.) ljubili(Fem.) |

bosta ljubila(Masc.) ljubili(Fem.) |

bosta ljubila(Masc.) ljubili(Fem.) |

| Plural | bomo ljubili(Masc.) ljubile(Fem.) |

boste ljubili(Masc.) ljubile(Fem.) |

bodo ljubili(Masc.) ljubile(Fem.) |

Conditional present

[edit]| Singular | bi lübo(Masc.) lübila(Fem.) |

bi lübo(Masc.) lübila(Fem.) |

bi lübo(Masc.) lübila(Fem.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dual | bi lübila(Masc.) lübili(Fem.) |

bi lübila(Masc.) lübili(Fem.) |

bi lübila(Masc.) lübili(Fem.) |

| Plural | bi lübili(Masc.) lübile(Fem.) |

bi lübili(Masc.) lübile(Fem.) |

bi lübili(Masc.) lübile(Fem.) |

| Singular | bi ljubil(Masc.) ljubila(Fem.) |

bi ljubil(Masc.) ljubila(Fem.) |

bi ljubil(Masc.) ljubila(Fem.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dual | bi ljubila(Masc.) ljubili(Fem.) |

bi ljubila(Masc.) ljubili(Fem.) |

bi ljubila(Masc.) ljubili(Fem.) |

| Plural | bi ljubili(Masc.) ljubile(Fem.) |

bi ljubili(Masc.) ljubile(Fem.) |

bi ljubili(Masc.) ljubile(Fem.) |

Lexicon

[edit]The Prekmurian Slovene vocabulary is very rich[74] and is significantly different from the Standard Slovene vocabulary. The dialect includes many archaic words that have disappeared from modern Slovene. Along with the three dialects spoken in Venetian Slovenia and the Slovene dialects of eastern Carinthia, Prekmurje Slovene is considered the most conservative of all Slovene dialects with regard to vocabulary.[citation needed]

The Prekmurian Slovene greatly expanded its vocabulary from the other Slavic languages (mainly from Kajkavian Croatian, Standard Slovene, Styrian Slovene, Serbo-Croatian, partly from the Czech and Slovak) and non-Slavic languages (mainly from Hungarian and German,[75] partly from Latin and Italian).[76] The more recently borrowed and less assimilated words are typically from English.

Comparison

[edit]| Prekmurian Slovene | Standard Slovene | Kajkavian Croatian | Serbo-Croatian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bajžlek | bazilika | bajžulek, bažuljek | bosiljak | basil |

| bejžati | hiteti, teči | bežati | trčati | run |

| betvo | betev | betvo | stabljika | stem |

| blejdi | bled | bledi | blijed | white-faced |

| bliskanca | bliskavica | bliskavica, blesikavec | blistanje | flashing |

| bougati | ubogati | poslušati | pokoravati se, slušati | submit |

| brač | trgač | brač | berač | vintager |

| brbrati, brbravi | klepetati, klepetav | brbotati, brblivi, brbotlivi | brbljati, brbljavi | chatter, chatterbox |

| comprnjak | čarovnik, čarodej | coprnik carovnik | čarobnjak | wizard |

| cükati | lulati | cukati | piškiti | urinate |

| čarni, črni | črn | črni | crn | black |

| česnek | česen | česen, češnjak | češnjak | garlic |

| činiti | delati, opravljati | činiti | činiti | make |

| čun | čoln | čun | čamac | boat |

| čüti | slišati | čuti | čuti | hear |

| den | dan | den | dan | day |

| dečko | fant, deček | dečko | dečak | boy |

| deklina, dekla | deklica | devojka | devojka | girl |

| delati | delati | delati | raditi | work |

| dokeč | dokler | doklam, dok | dok | until |

| dveri | vrata | vrata | vrata | door |

| fala | hvala | fala/hvala | hvala | thanks, gratitude |

| fčela | čebela | čmela | pčela | bee |

| fčera/včera | včeraj | čera | jučer | yesterday |

| geniti | ganiti | genuti | ganuti | move |

| ge | kje, kjer | de, gde | gdje | where |

| gorice | vinograd | trsje | vinograd | vineyard |

| grbanj | jurček | vrganj | vrganj | penny bun |

| gnes, gnjes | danes | denes | danas | today |

| gnüs | gnus | gnus, gnjus | gnus | disgust |

| gostüvanje | ženitovanje | goščenje | svadba | wedding |

| goušča | gozd | šuma | šuma | forest |

| gučati | govoriti | govoriti | govoriti | speak, talk |

| grüška | hruška | hruška | kruška | pear |

| inda | nekoč | negda | nekada | once |

| istina | resnica | istina | istina | truth |

| iža | hiša | hiža | kuća | house |

| Jezuš Kristuš | Jezus Kristus | Jezuš Kristuš | Isus Krst | Jesus Christ |

| ka | kaj | kaj | što | what |

| ka | da | da | da | that |

| ka | ker | arold jernew | jer | as |

| kakši | kakšen | kakvi | kakov | what |

| kama | kam, kamor | kam | kamo | to where |

| kapla | kaplja | kaplja, kapla | kapljica | drop |

| keden, tjeden | teden | tjeden | tjedan | week |

| kelko | koliko | kulko, kuliko | koliko | how much |

| kisili | kisel | kisel | kiseo | sour |

| kitina | kutina | kutina | dunja | quince |

| klejt | klet, shramba | sramba | podrum | cellar |

| klün | kljun | klun | kljun | beak |

| kmica | tema | tmica, kmica | tama, tmina | darkness |

| koupanca | kopalnica | kopel | kupatilo | bathroom |

| kopün | kopun | kopon, kopun | kopun | capon |

| koula | voz | kola, vozica | kola | cart |

| krapanca | krastača | krastača | krastača | toad |

| krpliva | kopriva | kopriva | kopriva | nettle |

| krpüšnica | robidnica, robida | kupina | kupina | blackberry |

| krumpiš, krumpič, krumše | krompir | krumpir | krumpir | potato |

| krüj | kruh | kruh | hlijeb, kruh | bread |

| krv | kri | krv | krv | blood |

| kukorca | koruza | kuruza | kuruza | corn |

| küščar | kuščar | kuščer | gušter | lizard |

| lapec | hlapec | hlapec | sluga | servant |

| ledičen | samski | ledičen | samac | bachelor |

| lejko | lahko | lehko | lako | possible |

| len | lan | len | lan | flax |

| lice | obličje | lice | lice | face |

| liki | toda, ampak | nego | međutim, ali | but |

| loški | divji | divji | divlji | wild (plant) |

| lübezen | ljubezen | ljubav, lubav | ljubav | love |

| mejšati | mešati | mešati | miješati | mix |

| meša | maša | meša | misa | mass |

| metül | metulj | metul, metulj | leptir | butterfly |

| mouč | moč | jakost | jakost | power |

| modroust | modrost | mudrost | mudrost | wisdom |

| Möra, Müra | Mura | Mura | Mura | Mura (river) |

| mrejti | umreti | hmreti, vumreti | umreti | die |

| mrlina | mrhovina, crkovina | mrcina | lešina | corpse |

| miditi | muditi | muditi | kasniti | be late |

| müja | muha | muha | muha | fly |

| nači(k) | drugače | inače | inače | other |

| natelebati | natepsti | nabobotati, namlatiti | istuči | beat |

| nedela | nedelja | nedela | nedjelja | sunday |

| nigdar | nikoli | nigdar | nikada | never |

| nigi | nikjer | nigde, nigdi | nigdje | nowhere |

| nikak | nikakor | nikak | nikako | no way |

| nojet | noht | nohet | nokat | nail |

| norija | norost, neumnost | norost, norija | glupost |

foolishness |

| obed, obid, oböd | kosilo | obed | ručak | lunch |

| oditi | hoditi | hoditi | hoditi | move |

| odzaja | odzadaj, zadaj | odzaj | odostraga | from behind |

| ograd | vrt | vrt | vrt | garden |

| ovak | drugače | inače | inače | other |

| öček | sekirica | sekirica | sjekira | ax |

| pajžli | parkelj | parkel | kopita | hoof |

| paroven | pohlepen, požrešen | paraven | proždrljiv | gluttonous |

| paska | pazljivost | paska | skrbljenje | prudence |

| pejati | bosti | pehati | ubosti | prod |

| pejsek | pesek | pesek | pijesak | sand |

| pesen | pesem | pesem | pjesma | song |

| pondejlek | ponedeljek | pondelek | ponedjeljak | monday |

| pitati, pitanje | vprašati, vprašanje | pitati, pitanje | pitati, pitanje | ask, question |

| plantavi | šepav | šantavi, plantavi | šepav, šantav | lame |

| plastič | kopica, kopa | stok | plast sena | haycock |

| plüča | pljuča | pluča | pluća | lung |

| plüskati | klofutati | pluskati | ošamariti | slap |

| poboukšati | poboljšati | pobolšati | poboljšati | improve |

| pogača | potica | pogača | pogača | scone |

| pojeb, pojbič | fant, fantič | dečec | dečak | boy |

| pokapanje | pokop | pokapanje | pogreb | burial |

| pozoj | zmaj | pozoj | zmaj | dragon |

| pükša | puška | puška, pušak | puška | riffle |

| praviti | reči | reči | reći | say |

| püščava | puščava | pustina | pustinja | desert |

| radost | veselje | radost | radost | joy |

| ranč tak, gli tak | prav tako | ravno tak | isto tako | alike |

| rasoje, rašoške | vile, vilice | rasohe | vile, viljuška | pitchfork, fork |

| rejč | beseda | reč | riječ | word |

| sklejca | skleda, krožnik | zdela | zdjela | dish |

| sledi, sledkar | kasneje | stopram | kasnije | later |

| slejpi | slep | slepi | slijep | blind |

| smej | smeh | smeh | smijeh | laugh |

| spitavati | izpraševati, spraševati | spitavati | ispitavati | interrogate |

| sprejvod | pogreb | sprevod, pogreb | pogreb | funeral |

| spuniti | izpolniti | spuniti | ispuniti | fulfil |

| stüdenec | vodnjak | zdenec | bunar | well |

| sunce | sonce | sunce | sunce | sun |

| svaja | prepir | svaja | svađa | conflict |

| ščava | kislica | ščava | štavelj | sorrels |

| šinjek | vrat, tilnik | šinjak | vrat | neck |

| šoula, škola | šola | škola | škola | school |

| školnik | učitelj | školnik | učitelj | teacher |

| škrampeu | krempelj | krampel | pandža | claw |

| taca | šapa | taca | šapa | paw |

| telko | toliko | tulko, tuliko | toliko | that much |

| tejlo | telo | telo | tijelo | body |

| tenja | senca | senca | zasenak | shadow |

| tou | to | to, ovo | to, ovo | this |

| trplenje | tprljenje | muka | muka | pain |

| trüd | trud | trud | napor | effort |

| türen, tören | stolp | turem | toranj | tower |

| ugorka | kumara | vugorek | krastavac | cucumber |

| vaga | tehtnica | vaga | vaga | scales |

| veleti | ukazati | veleti | naređivati | instruct |

| vejnec | venec | venec | vjenac | wreath |

| vonjati | smrdeti | smrdeti | smrdeti | smell |

| vonjüga | smrad | smrad | smrad | stench |

| vüpati, vüpanje | upati, upanje | vufati, vufanje | ufati, ufanje | hope, trust |

| vživati | uživati | vživati | uživati | enjoy |

| zajtra | zjutraj | vjutro | ujutro | morning |

| zoubar | zobozdravnik | zobar | zubar | dentist |

| zveličanje | zveličanje | zveličenje | spasenje | redemption |

| žalec | želo | žalec | žaoka | sting |

| žmeten | težek | teški | teški | heavy |

| žnjec | žanjec | žnjač | žetelac | harvester |

| žuč | žolč | žuč | žuč | bile |

| žuna | žolna | žuna | detlić | woodpecker |

| župa | juha | juha | supa | soup |

Loanwords

[edit]Prekmurian Slovene has also today many foreign words of mostly German and Hungarian origin.[77] The German loanwoards German mainly come from the Austro-Bavarian dialect.[78] There is still a strong German influence in Goričko dialect.[79]

| Prekmurian Slovene | Hungarian | Standard Slovene | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| beteg, betežen | betegség, beteg | bolezen, bolan | illness, ill |

| čonta, čunta | csont | kost | bone |

| engriš | egres | kosmulja | gooseberry |

| gezero, jezero | ezer | tisoč | thousand |

| pajdaš | pajtás | kamerad | buddy |

| laboška | lábas, lábos | kozica | pot |

| ugorka | uborka | kumara | cucumber |

| koudiš | koldus | berač | beggar |

| valon | való | veljaven | suitable |

| varaš | város | mesto | city, town |

| Prekmurian Slovene | German | Standard Slovene | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| brütif, brütof | Friedhof | pokopališče | cemetery |

| cajgar | Zeiger | kazalec | hand of watch |

| cigeu | Ziegel | opeka | brick |

| cimprati | zimmparon(Bav.) | graditi | build (with wood) |

| cug | Zug | vlak | train |

| cvek | zwëc(Middle High German) | žebelj | spike |

| dönok, denok | dennoch(Middle High German) | vendar | however |

| fabrika | Fabrik | tovarna | factory |

| fašenek | Fasching | pust | carnival |

| farba | Farbe | barva | color |

| farar | Pfarrer | duhovnik | protestant pastor |

| fejronga | Vorhang | zavesa | curtain |

| förtoj | Fürtuch(Bavarian) | predpasnik | woman apron |

| glaž | Glas | steklo | glass |

| gratati | geraten | postati, nastati | to arise |

| gvant | Gewand | obleka | clothes |

| lampe | Lippen | usta | mouth |

| pejgla | Bügeleisen | likalnik | clothes iron |

| plac | Plaz | trg | square |

| rafankeraš, rafankerar | Rauchfangkehrer | dimnikar | chimney-sweep |

| šalica | Schale(Bavarian) | skodelica | cup |

| šker | geschirre(Middle High German) | orodje | tool |

| špilati | spielen | igrati | play |

| šrajf | Schrafe(Bavarian) | vijak | screw |

| šraklin | Schürhakel | žarač, grebača | fire rake |

| žajfa | Seife | milo | soap |

We also find Latin loanwords: bauta, bunta (storage, Lat. voluta, Stand. Slov. trgovina), cintor (cemetery, Lat. coementerium, Stand. Slov. pokopališče), kanta (can, Lat. canna, Stand. Slov. ročka), oštarija (inn, Italian osteria, Stand. Slov. gostilna), upkaš (hoopoe, Lat. upupa, Stand. Slov. smrdokavra) etc.

Loanwords adopted from the Serbo-Croatian during Yugoslavia: dosaden (tedious, Serbo-Croatian dosadan, Stand. Slov. dolgočasen), novine (newspaper, Serbo-Croatian novine, Stand. Slovene časopis), život (live, Serbo-Croatian život, Stand. Slov. življenje).

Prekmurje Slovene dialects

[edit]- Hill country or Highlands dialect (Goričko),[80] in Upper Prekmurje, in locations of Grad, Gornji Petrovci, Križevci, Kuzma, Kuzma, Rogašovci, Šalovci, Mačkovci.

- Raba March subdialect (Porabje), in Hungary, part of the Goričko dialect.[81]

- Lowland dialect (Ravensko),[80] Central Prekmurje, in locations of Puconci, Cankova, Bogojina, Bakovci, Tišina, Petanjci, Moravske Toplice, Rakičan.

- Murska Sobota subdialect, the speech of the city Murska Sobota. Part of the Ravensko dialect.

- Lower Lowland dialect (Dolinsko)[80] in South Prekmurje, in locations Beltinci, Bratonci, Črenšovci, Velika Polana, Turnišče, Žižki, Renkovci, Bistrica (Dolnja, Gornja and Srednja). Other name is Markovsko, Markasto dialect, because of the prevalence of the personal name Marko (Marc) in old times.[80]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The Prekmurje Slovene developed from the language of the Carantanian Slavs who settled around Balaton in the 9th century. Due to the political and geographical separation from other Slovene dialects (unlike most of contemporary Slovenia, which was part of the Holy Roman Empire, Prekmurje was under the authority of the Kingdom of Hungary for almost a thousand years), the Prekmurje Slovene acquired many specific features. Separated from the cultural development of the remainder of ethnic Slovene territory, the Slovenes in Hungary gradually forged their own specific culture and also their own literary language.

In the end of the 16th century some Slovene Protestant pastor supported breaking away from Hungary. The pastors brought along the Bible of Primož Trubar and used it in Gornji Petrovci. Hungarian Slovenes found it difficult to understand the language of this book.

18th century

[edit]The first book in the Prekmurje Slovene appeared in 1715, and was written by the Lutheran pastor Ferenc Temlin. In the 18th and early 19th century, a regional literature written in Prekmurje Slovene flourished. It comprised mostly (although not exclusively) of religious texts, written by both Protestant and Catholic clergymen. The most important authors were the Lutheran pastor István Küzmics and the Roman Catholic priest Miklós Küzmics who settled the standard for the Prekmurje regional standard language in the 18th century. Both of them were born in central Prekmurje, and accordingly the regional literary language was also based on the central sub-dialects of Prekmurje Slovene.

Miklós Küzmics in the 1790s rejected Standard Slovene. The poet, writer, translator, and journalist Imre Augustich made approaches toward standard Slovene,[10][82] but retained the Hungarian alphabet. The poet Ferenc Sbüll also made motions toward accepting standard Slovene.

By the 16th century, a theory linking the Hungarian Slovenes to the ancient Vandals had become popular.[which?] Accordingly, Prekmurje Slovene was frequently designated in Hungarian Latin documents as the Vandalian language (Latin: lingua vandalica, Hungarian: Vandál nyelv, Prekmurje Slovene: vandalszki jezik or vandalszka vüszta).

With the advent of modernization in the mid-19th century, this kind of literature slowly declined. Nevertheless, the regional standard continued to be used in religious services. In the last decades of the 19th and 20th century, the denomination "Wends" and "Wendish language" was promoted, mostly by pro-Hungarians, in order to emphasize the difference between the Hungarian Slovenes and other Slovenes, including attempts to create a separate ethnic identity.

In 1919, most of Prekmurje was assigned to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and Slovene replaced Hungarian as the language of education and administration. Standard Slovene gradually started to replace Prekmurje Slovene in the local Roman Catholic church, while the Lutheran community continued to use the dialect in their religious services. The local press tried to combine the old Prekmurje regional standard with standard Slovene, making it completely intelligible to Slovenes from other regions. In the late 1920s and 1930s, many Slovenes from the Julian March who fled from Fascist Italy settled in Prekmurje, especially in the town of Lendava. The Yugoslav authorities encouraged the settlements of Slovene political immigrants from the Kingdom of Italy in Prekmurje as an attempt to reduce the influence of the Magyar element in the region; besides, the western Slovene dialects were very difficult to understand for the people of Prekmurje, thus the use of standard Slovene became almost indispensable for the mutual understanding.[83]

After World War II, the Lutheran Church also switched to standard Slovene in most of its parishes, and Prekmurje Slovene has since been relegated to almost exclusively private use. Nevertheless, along with Resian, the Prekmurje Slovene is one of the few Slovene dialects still used by most speakers, with very little influence from standard Slovene.[citation needed] This creates a situation of diglossia, where the dialect is used as the predominant means of communication in private life, while the standard language is used in schools, administration, and the media. The situation is different among the Hungarian Slovenes, where standard Slovene is still very rarely used.

19th century

[edit]A second wave of standardisation began in 1823. Mihály Barla issued a new hymnbook (Krscsanszke nove peszmene knige). József Kossics, a great writer and poet from Ptrekmurje, made contact with the Slovenian linguist Oroslav Caf and thus get acquainted with the Styrian Slovenian dialect. Kossics's father was of Croatian descent, and accordingly was also raised in the Kajkavian Croatian language. The Krátki návuk vogrszkoga jezika za zacsetníke, a Slovenian-Hungarian grammar book and dictionary let out the standard Prekmurje Slovene. The Zobriszani Szloven i Szlovenszka med Mürov in Rábov ethic-book, formed the ethics- and linguistic-norms. Zgodbe vogerszkoga králesztva and Sztarine Zseleznih ino Szalaszkih Szlovencov are the first Prekmurje Slovene Slovenian history books. Kossics was the first writer to write nonreligious poetry.

In 1820, a teacher named István Lülik wrote a new coursebook (Novi abeczedár), into which was made three issue (1853, 1856, 1863).

Sándor Terplán and János Kardos wrote a psalm book (Knige 'zoltárszke).

János Kardos translated numerous verses from Sándor Petőfi, János Arany and few Hungarian poet. In 1870, he worked on a new coursebook, the Nôve knige cstenyá za vesznícski sôl drügi zlôcs. In 1875, Imre Augustich established the first Prekmurje Slovene newspaper Prijátel (The Friend). Later, he wrote a new Hungarian–Prekmurje Slovene grammar (Návuk vogrszkoga jezika, 1876) and translated works from Hungarian poets and writers.

In 1886, József Bagáry wrote second course-book, which apply the Gaj alphabet (Perve knige – čtenyá za katholičánske vesničke šolê).

20th century

[edit]In 1914-1918, the ethnic governor and later parliamentarian congressman in Belgrade József Klekl standardized Prekmurje Slovene,[10] making use of the Croatian and Slovene languages. In 1923, the new prayerbook's Hodi k oltarskomi svesti (Come on to the Eucharist) orthography was written in the Gaj. Items in the newspapers the catholic Novine, Marijin list, Marijin ograček, calendar Kalendar Srca Jezušovoga, the Lutheran Düševni list and Evangeličanski kalendar were written in the Prekmurje Slovene.[84]

József Szakovics took an active part in cultivating the Prekmurje Slovene, although not all schools offered education in Prekmurje Slovene. The prominent Prekmurje writer Miško Kranjec also wrote in Slovene.

János Fliszár wrote a Hungarian-Wendish dictionary in 1922. In 1941, the Hungarian Army seized back the Prekmurje area and by 1945 aimed to make an end of the Prekmurje Slovene and Slovene by the help of Mikola.[clarification needed]

After 1945, Communist Yugoslavia banned the printing of religious books in the Prekmurje Slovene, and only standard Slovene was used in administration and education. In Hungary, the dictator Mátyás Rákosi banned every minority language and deported the Slovenes in the Hungarian Plain.

The Wendish question

[edit]This article may lack focus or may be about more than one topic. (November 2010) |

The issue of how Prekmurje Slovene came to be a separate tongue has many theories. First, in the 16th century, there was a theory that the Slovenes east of the Mura were descendants of the Vandals, an East Germanic tribe of pre-Roman Empire era antiquity. The Vandal name was used not only as the "scientific" or ethnological term for Slovenes, but also to acknowledge that the Vandalic people were named the Szlovenci, szlovenszki, szlovenye (Slovenians).

In 1627, was issue the Protestant visitation in the country Tótság, or Slovene Circumscription (this is the historical name of the Prekmurje and Vendvidék, Prekmurje Slovene: Slovenska okroglina).[clarification needed] Herein act a Slavic Bible in Gornji Petrovci, which as a matter of fact the Bible of Primož Trubar. From Carniola and Styria in the 16th and 17th centuries, a few Slovene Protestant pastors fled to Hungary and brought with them Trubar's Bible, which helped set the standard for Slovene. Not known by accident there was work on Prekmurje Slovene.[clarification needed]

According to the Hungarian dissenters, the Wendish (Prekmurje Slovene) language was of Danish, Sorbian, Germanic, Celtic, Eastern Romance or West Slavic extraction.[citation needed] But this was often false, political or exaggerated affirmations.

According to extremist Hungarian groups, the Wends were captured by Turkish and Croatian troops who were later integrated into Hungarian society. Another popular theory created by some Hungarian nationalists was that the speakers of the Wendish language were "in truth" Magyar peoples, and some had merged into the Slavic population of Slovenia over the last 800 years.

In 1920, Hungarian physicist Sándor Mikola wrote a number of books about Slovene inhabitants of Hungary and the Wendish language: the Wendish-Celtic theory. Accordingly, the Wends (Slovenians in Hungary) were of Celtic extraction, not Slavic. Later Mikola also adopted the belief that the Wends indeed were Slavic-speaking Hungarians. In Hungary, the state's ethnonationalistic program tried to prove his theories. Mikola also thought the Wends, Slovenes, and Croatians alike were all descendants of the Pannonian Romans, therefore they have Latin blood and culture in them as well.

During the Hungarian revolution when Hungarians rebelled against Habsburg rule, the Catholic Slovenes sided with the Catholic Habsburgs. The Lutheran Slovenians, however, supported the rebel Lajos Kossuth siding with Hungary and they pleaded for the separation of Hungary from Habsburg Austria which had its anti-Protestant policy. At that time, the reasoning that the inhabitants of the Rába Region were not Slovenes but Wends and "Wendish-Slovenes" respectively and that, as a consequence, their ancestral Slavic-Wendish language was not to be equated with the other Slovenes living in the Austro-Hungarian Empire was established. In the opinion of the Lutheran-Slovene priest of Hodoš, the only possibility for the Lutheran Slovenes emerging from the Catholic-Slovenian population group to continue was to support Kossuth and his Hungarian culture.[clarification needed] Thereafter, the Lutheran Slovenes used their language in churches and schools in the most traditional way in order to distinguish themselves from the Catholic Slovenes and the Slovene language (i.e., pro-Hungarian or pan-Slavic Slovene literature). The Lutheran priests and believers remained of the conviction that they could only adhere to their Lutheran faith when following the wish of the Hungarians (or the Austrians) and considering themselves "Wendish-Slovenes". If they did not conform to this, then they were in danger of being assimilated into Hungarian culture.

In the years preceding World War I, the Hungarian Slovenes were swept into the ideology of Panslavism, the national unity of all Slavic-speaking peoples of Eastern Europe. The issue was volatile in the fragmented Austro-Hungarian empire, which was defeated in the war. In the 1921 Treaty of Trianon, the southern half (not the whole) of the Prekmurje region was ceded to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

The Hungarian government in Budapest after 1867 tried to assimilate the Prekmurje Slovenes. In Somogy in the 19th century, there was still a ban on using Prekmurje Slovene. József Borovnyák, Ferenc Ivanóczy, and other Slovenian politicians and writers helped safeguard the Prekmurje Slovene and identity.

In the late 20th century and today, the new notion for Hungarian Slovenians is to conceive Prekmurje Slovene is in fact the Slovene language, but not dialect.[clarification needed] Their allusions: the Küzmics Gospels, the Old Grammar- and state-run public schools, the typical Prekmurje Slovene and Rába Slovene culture, the few centuries old-long isolation in Prekmurje Slovene and continued self-preservation from the Hungarian majority. The Hungarian Slovenes are more interested in being Slovenes.[citation needed] In Communist Yugoslavia, Prekmurje Slovene was looked down upon because numerous writers, such as József Klekl, were anti-communists.[85][86]

However, pseudoscientic and extremist theories continue to be propagated. Ethnological research has again looked into the "Celtic-Wends, Wendish-Magyars", "Pannonian Roman" and West Slavic theories. Tibor Zsiga, a prominent Hungarian historian in 2001 declared "The Slovene people cannot be declared Wends, neither in Slovenia, neither in Prekmurje." One may mind the Slovene/Slovenski name issue was under Pan-Slavism in the 19th-20th century, the other believes the issue was purely political in nature.

Examples

[edit]A comparison of the Lord's Prayer in standard Slovene, Standard Prekmurje Slovene, Kajkavian Croatian, and standard Croatian. The Prekmurje Slovene version is taken from a 1942 prayer book (Zálozso János Zvér, Molitvena Kniga, Odobrena od cérkvene oblászti, Murska Sobota, 1942, third edition). The original Hungarian orthography has been transliterated into Gaj's Latin alphabet, as used in the other versions, for easier comparison.

| Standard Slovene | Standard Prekmurje Slovene | Standard Kajkavian | Standard Croatian |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Oče naš, ki si v nebesih, |

Oča naš, ki si vu nebésaj! |

Otec naš, koji jesi v nebesih, |

Oče naš, koji jesi na nebesima, |

Trivia

[edit]In 2018 a Prekmurje Slovene translation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's The Little Prince was published.[87]

Singer and songwriter Nika Zorjan in 2018 created the Prekmurje Slovene version of Mariah Carey's All I Want for Christmas Is You aka Fse ka bi za Božič.[88][89]

Gallery

[edit]-

The first printed book in Prekmurje Slovene: Mali cathecismus (Small Catechism), by Ferenc Temlin.

-

The ABC-book of Miklós Küzmics. This is also the first Hungarian-Slovenian Dictionary.

-

József Kossics: Small Grammar of the Hungarian language and Vandalic language. The work of Kossics was farther from Prekmurje Slovene.

-

The gradual of Mihály Bakos.

-

The famous Prekmurje Slovene prayer-book, the Kniga molitvena from 1855.

-

Pray my brothers! Prayer-book of József Szakovics in 1936. His script was written in the Slovene alphabet.

-

The tomb of the young Vince Talabér from Permise (Kétvölgy) in the cemetery of Apátistvánfalva with Prekmurje Slovene inscription.

-

Prekmurje Slovene gravestone in the United States (St. Michael's Cemetery, South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania)

-

Sándor Terplán: Dvakrat 52 Bibliszke Historie (Twice 52 historie from Bible) in 1847.

-

Kalendar Srca Jezušovoga (Jesus's Heart Calendar) was Prekmurje Catholic calendar between 1904 and 1944.

-

The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden – picture from Mála biblia z-kejpami (Small Bible with pictures) by Péter Kollár (1897).

See also

[edit]- Languages of Slovenia

- List of Slovene writers and poets in Hungary

- Slovene March (Kingdom of Hungary)

- Vandalic language

- János Fliszár

- József Klekl (politician)

- Ágoston Pável

References

[edit]- ^ a b Damir Josipovič: Prekmurje in prekmurščina (Anali PAZU - Letnik 2, leto 2012, številka 2)

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 1:"There is reason to think of Prekmurje Slovene as a dialect of Slovene as well as a separate language. Indeed it has carried through many of the innovations that are characteristic of Slovene, shares most core vocabulary and grammatical structure, and from this perspective is part of a broader dialect group of the Pannonian group of Slovene dialects, together with the Slovenske gorice, Prlekija, and Haloze dialects, which in turn share a number of characteristics that differ from the rest of Slovene as well as neighboring Kajkavian dialects in Croatia (see Ramovš 1935, 171–193 for details). In favor of Prekmurje Slovene as a language it is written tradition, as it has been used for several centuries in a loosely standardized form, largely, but not exclusively, as a liturgical language. From a diachronic perspective, the Prekmurje Slovene offers a glimpse at a linguistic code that came into being through heterogeneous processes."

- ^ Logar, Tine. 1996. Dialektološke in jezikovnozgodovinske razprave. Ljubljana: SAZU, p. 240.

- ^ "Zapostavljeni spomin pokrajine - Prekmurska zgodovina kot primer spregleda lokalne zgodovine v učnem načrtu osnovnih in srednjih šol" [Neglected memory of a region - history of Prekmurje as an example of overlooked local history in curriculum of primary and secondary schools] (in Slovenian). Javna agencija za raziskovalno dejavnost Republike Slovenije [Slovenian Research Agency] (AARS). 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jesenšek, Marko (2008). "Trubarjeva in Küzmičeva različica slovenskega knjižnega jezika" [Trubar's and Küzmič's Variants of the Slovene Literary Language] (PDF). Slavistična revija (in Slovenian and English). Vol. 56, no. 4. COBISS 16738056.

- ^ RTV SLO: Nova radijska igra Bratonski pil v prekmurščini

- ^ Prekmurščina: Dnejvi so minejvali pa nika takšoga se nej zgoudilo (Dnevnik)

- ^ Prekmurci in prekmurščina (Prekmursko društvo General Maister)

- ^ NE SPREGLEJTE! Na TV IDEA nova oddaja TIJ SAMO GUČI z gostiteljem Mišem Kontrecem (Sobotainfo)

- ^ a b c d e Imre, Szíjártó (October 2007). "Muravidéki szlovén irodalom; A Muravidék történelmi útja" [Prekmurje Slovene literature; The Prekmurje historical journey] (PDF). Nagy Világ (in Hungarian): 777–778. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21.

- ^ F. Just: Med verzuško in pesmijo →Prekmurska jezikovna vojna, 73. page

- ^ Slovenski koledar (1992) ISSN 0237-1480, 98. p.

- ^ "Zapis 34. posveta predstavnikov verskih skupnosti, ki so prijavile svojo ustanovitev v Republiki Sloveniji" (PDF) (in Slovenian).

- ^ Nekaj manjka v naših šolah ... To je prekmurščina!

- ^ Prekmurščina kot predmet v osnovnih in srednjih šolah? (sobotainfo.com)

- ^ Spoznaj nosilca enote Ptuj: Rolando Benjamin Vaz Ferreira (piratskastranka.si)

- ^ F. Just: Med verzuško in pesmijo →„Poslünte, da esi prosim vas, gospoda, ka bom vam jas pravo od toga naroda” 10. 12. 14. page

- ^ "Prekmurski film Oča se danes predstavlja svetovni javnosti" (in Slovenian). Pomurec. 2010-09-07.

- ^ "MITNJEK VESNA S.P. ČARNA BAUTA" (in Slovenian).

- ^ Lovenjakov Dvor - Hotel Štrk

- ^ "Protesti v Murski Soboti" (in Slovenian). Pomurec.

- ^ Marko Jesenšek: Prekmuriana, Cathedra Philologiae Slavicae, Balassi Kiadó, Budapest 2010. ISBN 978-963-506-846-3

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Greenberg 2020, p. 21.

- ^ a b Greenberg 2020, p. 20.

- ^ Novak 1976, p. 69.

- ^ Lončar 2010, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Greenberg 2020, p. 24.

- ^ a b Greenberg 2020, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Greenberg 2020, p. 23.

- ^ a b Greenberg 2020, p. 29.

- ^ a b Greenberg 2020, p. 31.

- ^ Koletnik 2001, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Zorko 1998, pp. 25–47.

- ^ Moguš 1977, pp. 79–82.

- ^ Nowday: velika noč

- ^ a b c d e Greenberg 2020, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Greenberg 2020, p. 33.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 35.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 51.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 50.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, p. 271.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 53.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, p. 290.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 59.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, pp. 293–295.

- ^ a b c Greenberg 2020, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b Toporišič 2004, pp. 323–325.

- ^ a b Greenberg 2020, p. 62.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, pp. 277–278.

- ^ Kühar 1913, p. 20a..

- ^ Toporišič 2004, p. 288–289.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, p. 321.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 67.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, p. 299.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, p. 297.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 85.

- ^ a b c Toporišič 2004, p. 305.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Kühar 1913, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 86.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, p. 306.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 97.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, pp. 329–331.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Greenberg 2020, p. 110.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, pp. 369–370.

- ^ a b Greenberg 2020, p. 111.

- ^ Toporišič 2004, p. 373.

- ^ a b Toporišič 2004, p. 388.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Ulčnik 2007, pp. 678–679.

- ^ Trajber 2010, p. 72.

- ^ Ulčnik 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Greenberg 2020, p. 185.

- ^ Novak & Novak 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Trajber 2010, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b c d Greenberg 2020, p. 16.

- ^ Zorko 2009, p. 285.

- ^ F. Just: Med verzuško in pesmijo →„Poslünte, da esi prosim vas, gospoda ka bom vam jas pravo od toga naroda,” 19. page

- ^ Göncz, László. "A muravidéki magyarság 1918-1941" [The Hungarians in Prekmurje 1918-1941]. Hungarian Electronic Library (in Hungarian).

- ^ F. Just: Med verzuško in pesmijo →„Pride čas, i ne je daleč, gda bomo vu našem maternom jeziki čteli dobra, čedna, poštena, düši i teli hasnovita dela.” 26.-53. page

- ^ Janez Votek: Raznarodovanje rodilo srečne sadove, Vestnik 49./21. Murska Sobota (22.05.1997), 8. p.

- ^ Stanislav Zver: Jožef Klekl prekmurski Čedermac, Ognjišče 2001. ISBN 961-6308-62-9, pp. 111-112

- ^ Mali princ tudi v prekmurščini (vestnik.si)

- ^ Svetovno znan božični hit dobil prekmursko verzijo (prlekija.net)

- ^ NIKA ZORJAN-FSE, KA BI ZA BOŽIČ BESEDILO (YouTube)

Bibliography

[edit]- Greenberg, Marc L. (2020). Fortuin, Egbert; Houtzagers, Peter; Kalsbeek, Janneke (eds.). Prekmurje Slovene Grammar: Avgust Pavel's Vend nyelvtan (1942). Critical edition and translation from Hungarian by Marc L. Greenberg. Leiden, Boston: Brill Rodopi. ISBN 978-9004419117.

- Koletnik, Mihaela (2001). Slovenskogoriško narečje. Maribor: Mednarodna založba Oddelka za slovanske jezike in književnosti, Filozofska fakulteta, Univerza v Mariboru. ISBN 961-6320-04-1.

- Kühar, Števan (1913). Slòvnica vogr̀sko-slovènskoga narêčja. Bratonci: Manuscript.

- Lončar, Nataša (2010). Ledinska in hišna imena v izbranih naseljih občine Cankova. Diplomsko delo. Maribor: Filozofska fakulteta Univerze v Mariboru. Oddelek za slovanske jezike in književnosti.

- Moguš, Milan (1977). Čakavsko narječje. Fonologija. Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

- Novak, Franc; Novak, Vilko (2009). Slovar beltinskega prekmurskega govora. Ponatis druge, popravljene in dopolnjene izdaje iz leta 1996, ki jo je priredil in uredil Vilko Novak. Murska Sobota: Pomurska založba. ISBN 978-961-249-068-3.

- Novak, Vilko (1976). Izbor prekmurskega slovstva. Ljubljana: Self-publishing.

- Novak, Vilko (1936). Izbor prekmurske književnosti. Cvetje iz domačih in tujih logov 9. Urejuje prof. Jakob Šolar s sodelovanjem uredniškega odbora. Celje: Družba Sv. Mohorja.

- Toporišič, Jože (2004). Slovenska slovnica. Četrta, prenovljena in razširjena izdaja. Maribor: Založba Obzorja. ISBN 961-230-171-9.

- Trajber, Aleksander-Saša (2010). Germanizmi v prekmurskem narečju. Diplomsko delo. Maribor: Filozofska fakulteta Univerze v Mariboru. Oddelek za germanistiko.

- Ulčnik, Natalija (2007). Bogastvo panonskega besedja. Slavistična revija. Letn. 55. Štev. 4. Ljubljana: Slavistično društvo Slovenije. pp. 675–679.

- Zorko, Zinka (1998). Haloško narečje in druge dialektološke študije. Maribor: Mednarodna založba Oddelka za slovanske jezike in književnosti, Filozofska fakulteta, Univerza v Mariboru. ISBN 961-90073-8-7.

- Zorko, Zinka (2009). Narečjeslovne razprave o koroških, štajerskih in panonskih govorih. Maribor: Mednarodna založba Oddelka za slovanske jezike in književnosti, Filozofska fakulteta, Univerza v Mariboru. ISBN 978-961-6656-37-5.

Sources

[edit]- Mária Mukics: Changing World - The Hungarian Slovenians (Változó Világ - A magyarországi szlovének) Press Publica

- Mukics Ferenc: Szlovén Nyelvkönyv/Slovenska slovnica (Slovenian language-book), 1997. ISBN 963-04-9261-X

- Vilko Novak Slovar stare knjižne prekmurščine, Založba ZRC, Ljubljana 2006. ISBN 961-6568-60-4

- Fliszár János: Magyar-vend szótár/Vogrszki-vendiski rêcsnik, Budapest 1922.

- Francek Mukič: Porabsko-knjižnoslovensko-madžarski slovar, Szombathely 2005. ISBN 963-217-762-2

- Greenberg, Marc L. (1989). "Ágost Pável's Prekmurje Slovene grammar" (PDF). Slavistična revija. 37 (1–3): 353–364.COBISS 15214592

- Greenberg, Marc L. (1992). "O pomiku praslovanskega cirkumfleksa v slovenščini in kajkavščini, s posebnim ozirom na razvoj v prekmurščini in sosednjih narečjih" [Circumflex advancement in Prekmurje and beyond] (PDF). Slovene Studies. 14 (1): 69–91.

- Marc L. Greenberg: Glasoslovni opis treh prekmurskih govorov in komentar k zgodovinskemu glasoslovju in oblikoglasju prekmurskega narečja. Slavistična revija 41/4 (1993), 465-487.

- Marc L. Greenberg: Archaisms and innovations in the dialect of Središče: (Southeastern Prlekija, Slovenia). Indiana Slavic studies 7 (1994), 90-102.

- Marc L. Greenberg: Prekmurje grammar as a source of Slavic comparative material. Slovenski jezik 7 (2009), 28-44.

- Marc L. Greenberg: Slovar beltinskega prekmurskega govora. Slavistična revija 36 (1988). 452–456. [Review essay of Franc Novak, Slovar beltinskega prekmurskega govora [A Dictionary of the Prekmurje Dialect of Beltinci].

- Franci Just: Med verzuško in pesmijo, Poezija Prekmurja v prvi polovici 20. stoletja, Franc-Franc, Murska Sobota 2000. ISBN 961-219-025-9

- Vilko Novak: Slovar stare knjižne prekmurščine, Založba ZRC, Ljubljana, 2006. ISBN 961-6568-60-4

- Vilko Novak: Martjanska pesmarica, Založba ZRC, Ljubljana, 1997. ISBN 961-6182-27-7

- Vilko Novak: Zgodovina iz spomina/Történelem emlékezetből – Polemika o knjigi Tiborja Zsige Muravidéktől Trianonig/Polémia Zsiga Tibor Muravidéktől Trianonig című könyvéről, Založba ZRC, Ljubljana, 2004. ISBN 961-6500-34-1

- Anton Trstenjak: Slovenci na Ogrskem, Narodopisna in književna črtica, objava arhivskih virov MARIBOR 2006. ISBN 961-6507-09-5

- Marija Kozar: Etnološki slovar slovencev na Madžarskem, Monošter-Szombathely 1996. ISBN 963-7206-62-0

- Források a Muravidék történetéhez 1./Viri za zgodovino Prekmurja 1. Szombathely-Zalaegerszeg, 2008. ISBN 978-963-7227-19-6 Ö

- Források a Muravidék történetéhez/Viri za zgodovino Prekmurja 2. Szombathely-Zalaegerszeg 2008. ISBN 978-963-7227-19-6

- Molitvena Kniga, Odobrena od cérkvene oblászti, edit: József Szakovics 1942.

- Pokrajinski muzej Murska Sobota, Katalog stalne razstave, Murska Sobota 1997. ISBN 961-90438-1-2

- Jerneja Kopitarja Glagolita Clozianus/Cločev Glagolit, Ljubljana 1995. ISBN 86-7207-078-X

- Življenje in delo Jožefa Borovnjaka, Edit: Marko Jesenšek, Maribor 2008.

- Bea Baboš Logar: Prekmurska narečna slovstvena ustvarjalnost – mednarodno znanstveno srečanje: prekmurščina zanimiva tudi za tuje znanstvenike, Vestnik July 17, 2003.

- Predgovor. Nouvi Zákon, Stevan Küzmics, Pokrajinski Muzej Murska Sobota 2008. ISBN 978-961-6579-04-9 (Translations: in English Peter Lamovec; in Hungarian Gabriella Bence; in Slovene Mihael Kuzmič)

External links

[edit]- Marko Jesenšek: STILISTIKA PREKMURSKIH OGLAŠEVALSKIH BESEDIL/STYLISTICS IN ADVERTISING TEXTS IN PREKMURJE

- László Göncz: The Hungarians in Prekmurje 1918-1941 (A muravidéki magyarság 1918-1941)

- Hungarian books in Prekmurje Slovenian 1715-1919

- Hungarian books in Prekmurje Slovenian 1920-1944

- PREKMURSKI PUBLICISTIČNI JEZIK V PRVI POLOVICI 20. STOLETJA

- Američan, ki je doktoriral iz prekmurščine

- "Zame prekmurščina ni narečje, temveč jezik" – Branko Pintarič, gledališki ustvarjalec (For Me, Prekmurje Slovenian Is Not a Dialect, But a Language)

- Preučevanje jezika in literature (Slovene)

- Marko Jesenšek: The Slovene Language in the Alpine and Pannonian Language Area

- Six stories from Prekmurje (1)

![The prayer-book of József Szakovics in 1931. Print was János Zvér [sl] in Murska Sobota.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c6/Molitvena_Kniga_%281931%29.JPG/120px-Molitvena_Kniga_%281931%29.JPG)