Squash (sport)

A squash player prepares to strike the ball with his racket | |

| Highest governing body | World Squash Federation (WSF) |

|---|---|

| First played | 19th century, England, United Kingdom |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Limited |

| Team members | Singles or doubles |

| Mixed-sex | Separate competitions (mixed sometimes in leagues) |

| Type | Racket sport |

| Equipment | Squash ball, squash racket, goggles, non-marking gum soled shoes |

| Venue | Indoor or outdoor (with glass court) |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | To be included in 2028 Summer Olympics |

| World Games | 1997, 2005–present |

Squash, sometimes called squash rackets, is a racket-and-ball sport played by two (singles) or four players (doubles) in a four-walled court with a small, hollow, rubber ball. The players alternate in striking the ball with their rackets onto the playable surfaces of the four walls of the court. The objective of the game is to hit the ball in such a way that the opponent is not able to play a valid return. There are about 20 million people who play squash regularly world-wide in over 185 countries.[1] The governing body of squash, the World Squash Federation (WSF), is recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), and the sport will be included in the Olympic Games, starting with the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.[2] The Professional Squash Association (PSA) organizes the pro tour.

History

[edit]Squash has its origins in the older game of rackets, which was played in London's prisons in the 19th century. Later, around 1830, boys at Harrow School noticed that a punctured ball, which "squashed" on impact with the wall, offered more variety to the game. The game spread to other schools. The first courts built at Harrow were dangerous because they were near water pipes, buttresses, chimneys, and ledges. Natural rubber was the preferred material for the ball. Students modified their rackets to have a smaller reach and improve their ability to play in these cramped conditions.[3] In 1864, the school built four outside courts.[4]

In the 20th century, the game increased in popularity with various schools, clubs and private individuals building squash courts, but with no set dimensions. The first squash court in North America was at St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire, in 1884. In 1904 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the earliest national association of squash in the world, the United States Squash Racquets Association, now known as U.S. Squash, was formed. In April 1907, the Tennis, Rackets & Fives Association of Queens, New York, which regulated those three sports (fives being a similar sport using hands instead of a racket), established a subcommittee to set standards for squash. In 1912, the association published rules for squash,[3]: 38 combining aspects of these three sports.

In 1912, the RMS Titanic had a squash court in first class, available for 8 pence (£12.22 in 2022 terms). The 1st-Class Squash Court was situated on G-Deck. The Spectators Viewing Gallery was one level higher, on F-Deck. Passengers could use the court for one hour unless others were waiting.

In 1923, the Royal Automobile Club hosted a meeting to further discuss the rules and regulations. Five years later, the Squash Rackets Association, now known as England Squash, was formed to set standards for the game in Great Britain and internationally.[3] The rackets were made from one piece English ash, with a suede leather grip and natural gut.

The 1980s witnessed a period of restructuring and consolidation. The Cambridge rackets factory was forced to close in face of the move to graphite rackets, and production was moved to the Far East.[5] Customization of squash rackets has grown over the years as well. There are custom variations on racket head shape, racket balance, and racket weight. The most common racket variation for international singles squash is a teardrop (closed throat) head shape, even balance, and racket weight of 130g. For hardball doubles, the most common variation is an open throat head shape, even balance, and racket weight of 140g.

There are several variations of squash played across the world, although the international version of the sport has become the dominant form. In the United States, a variant of squash known as hardball was traditionally played with a harder ball and differently sized courts. Hardball squash has lost much of its popularity in North America (in favor of the international version). There is doubles squash a variant played by four players. There is also a tennis-like variation of squash known as squash tennis. Finally, racketball, a similar sport played on a squash court (as distinguished from racquetball), has been rebranded as Squash 57 by the World Squash Federation.

Equipment

[edit]Racket

[edit]

Squash rackets have maximum dimensions of 686 mm (27.0 in) long and 215 mm (8.5 in) wide, with a maximum strung area of 500 square centimeters (77.5 sq in). The permitted maximum weight is 255 grams (9.0 oz), but most have a weight between 90 and 150 grams (3–5.3 oz.). The strings of the racket usually have a tension of 25–30 pounds.

Ball

[edit]

Squash balls are between 39.5 and 40.5 mm in diameter and weigh 23 to 25 grams.[6] They are made with two pieces of rubber compound, glued together to form a hollow sphere and buffed to a matte finish. Different balls are provided for varying temperature and atmospheric conditions and standards of play: more experienced players use slow balls that have less bounce than those used by less experienced players (slower balls tend to "die" in court corners, rather than "standing up" to allow easier shots). Squash balls must be hit dozens of times to warm them up at the beginning of a session; cold squash balls have very little bounce. Small colored dots on the ball indicate its dynamic level (bounciness). The "double-yellow dot" ball, introduced in 2000, is the competition standard, replacing the earlier "yellow-dot" ball. There is also an "orange dot" ball for use at high altitudes. The recognized colors are:

| Colour | Speed (of Play) | Bounce | Player Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orange | Extremely Slow | Super low | Only recommended for high altitude play |

| Double yellow | Extra Slow | Very low | Experienced |

| Yellow | Slow | Low | Advanced |

| Green | Medium | Average | Intermediate/Advanced |

| Red | Medium | High | Medium |

| Blue | Fast | Very high | Beginner/Junior |

Some ball manufacturers such as Dunlop use a different method of grading balls based on experience. They still have the equivalent dot rating but are named to help choose a ball that is appropriate for one's skill level. The four different ball types are Intro (Blue dot, 140% of Pro bounce), Progress (Red dot, 120% of Pro bounce), Competition (single yellow dot, 110% of Pro bounce) and Pro (double yellow dot).

Many squash venues mandate the use of shoes with non-marking tread and eye protection. Some associations require that all juniors and doubles players must wear eye protection. The National Institutes of Health recommends wearing goggles with polycarbonate lenses.[7]

Court

[edit]

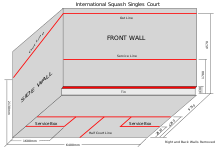

The squash court is a playing surface surrounded by four walls. The court surface contains a front line separating the front and back of the court and a half court line, separating the left and right sides of the back portion of the court, creating three 'boxes': the front half, the back left quarter and the back right quarter. The back two boxes contain smaller service boxes.

The court's four walls are divided into a front wall, two side walls, and a back wall. An 'out line' runs along the top of the front wall, descending along the side walls to the back wall. The bottom line of the front wall marks the top of the 'tin', a half meter-high metal area. The middle line of the front wall is the service line. The dimensions of the court are:[8]

| Dimensions | Distance | +/− |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 9750 mm | 10 mm |

| Width | 6400 mm | 10 mm |

| Height | 5640 mm | |

| Diagonals | 11,665 mm | 25 mm |

North American hardball doubles courts are larger than international singles courts because of a hard ball that has a much faster pace. With double the number of players, the doubles court needs to be significantly bigger than a singles court. The doubles court should measure 25 feet wide by 45 feet long and have a ceiling height of at least 24 feet but preferably 26.[9]

Manner of play

[edit]Service

[edit]The players spin a racket to decide who serves first. This player starts the first rally by electing to serve from either the left or right service box. For a legal serve, one of the server's feet must be in the service box, not touching any part of the service box lines, as the player strikes the ball. After being struck by the racket, the ball must strike the front wall above the service line and below the out line and land in the opposite back quarter court. The receiving player can choose to volley a serve after it has hit the front wall. If the server wins the point, the two players switch sides for the following point. If the server loses the point, the opponent then serves, and can serve from either box.

Play

[edit]

After the serve, the players take turns hitting the ball against the front wall, above the tin and below the out line. The ball may strike the side or back walls at any time, as long as it hits below the out line. It must not hit the floor after hitting the racket and before hitting the front wall. A ball landing on either the out line or the line along the top of the tin is considered to be out. After the ball hits the front wall, it is allowed to bounce once on the floor (and any number of times against the side or back walls) before a player must return it. Players may move anywhere around the court, but accidental or deliberate obstruction of the other player's movements is forbidden and could result in a let or a stroke. Players typically return to the centre of the court after making a shot, as it is the optimal position in the court to receive the opponent's shot. The centre of the court is typically referred to as "the T", named after the shape of the floor lines.

Strategy and tactics

[edit]A key strategy in squash is known as "dominating the T" (the intersection of the red lines near the centre of the court, shaped like the letter "T", where the player is in the best position to retrieve the opponent's next shot). Skilled players will return a shot, and then move back toward the "T" before playing the next shot. From this position, the player can quickly access any part of the court to retrieve the opponent's next shot with a minimum of movement and possibly maximising the movement required by the opponent to answer the returned shot.

A common tactic is to hit the ball straight up the side walls to the back corners; this is the basic squash shot, referred to as a "rail", straight drive, wall, or "length". After hitting this shot, the player will then move to the centre of the court near the "T" to be well placed to retrieve the opponent's return. Attacking with soft or "short" shots to the front corners (referred to as "drop shots") causes the opponent to cover more of the court and may result in an outright winner. Boasts or angle shots are deliberately struck off one of the side walls before the ball reaches the front. They are used for deception and again to cause the opponent to cover more of the court. Rear wall shots float to the front either straight or diagonally drawing the opponent to the front. Advantageous tactical shots are available in response to a weak return by the opponent if stretched, the majority of the court being free to the striker. Nicks are when the ball comes into contact with the intersection of the floor and any sidewall.

Rallies between experienced players may involve 30 or more shots and therefore a very high premium is placed on fitness, both aerobic and anaerobic. As players become more skilled and, in particular, better able to retrieve shots, points often become a war of attrition. At higher levels of the game, the fitter player has a major advantage.

The ability to change the direction of the ball at the last instant is also a tactic used to unbalance the opponent. Expert players can anticipate the opponent's shot a few tenths of a second before the average player, giving them a chance to react sooner.[10]

2 points during the Semi Final between James Willstrop and Nick Matthew in 2011.[11][12]

Depending on the style of play, it is common to refer to squash players[13][14] as

- Power players: powerful shots to take time away from their opponent. For example, John White, Omar Mosaad, Mohamed El Shorbagy, Nouran Gohar

- Shotmakers: accurate shots to take time away from their opponent. For example, Jonathon Power, Ramy Ashour, Amr Shabana, James Willstrop.

- Retrievers: excellent retrieval to counter power and accuracy and to return shots more quickly to take time away from their opponent. For example, Peter Nicol, Grégory Gaultier, Nicol David.

- Attritional players: a consistently high-paced game both from shot speed and running speed to wear their opponent down over time. For example, David Palmer, Nick Matthew, Jansher Khan, Jahangir Khan.

Interference and obstruction

[edit]Interference and obstruction are an inevitable aspect of squash, since two players are confined within a shared space. Generally, the rules entitle players to a direct straight-line access to the ball, room for a reasonable swing and an unobstructed shot to any part of the front wall. When interference occurs, a player may appeal for a "let" and the referee (or the players themselves if there is no official) then interprets the extent of the interference. The referee may allow a let and the players then replay the point or award a "stroke" to the appealing player (meaning that he is declared the winner of that point) depending on the degree of interference, whether the interfering player made an adequate effort to avoid interfering, and whether the player interfered with was likely to have hit a winning shot had the interference not occurred. An exception occurs when the interfering player is directly in the path of the other player's swing, effectively preventing the swing, in which case a stroke is always awarded.

When it is deemed that there has been little or no interference, the rules provide that no let is to be allowed in the interests of continuity of play and the discouraging of spurious appeals for lets. Because of the subjectivity in interpreting the nature and magnitude of interference, awarding (or withholding) of lets and strokes is often controversial.

Interference also occurs when a player's shot hits their opponent prior to hitting the front wall. If the ball was travelling towards the side wall when it hit the opponent, or if it had already hit the side wall and was travelling directly to the front wall, it is usually a let. However, it is a stroke to the player who hit the ball if the ball was travelling straight to the front wall when the ball hit the opponent, without having first hit the side wall. Generally, after a player has been hit by the ball, both players stand still; if the struck player is standing directly in front of the player who hit the ball, he loses the stroke; if he is not straight in front, a let is played. If it is deemed that the player who is striking the ball is deliberately trying to hit his opponent, they will lose the stroke. An exception occurs when the player hitting the ball has "turned", i.e., letting the ball pass them on one side, but then hitting it on the other side as it came off the back wall. In these cases, the stroke goes to the player who was hit by the ball.

Referee

[edit]The referee is usually a certified position issued by the club or assigned squash league. Any conflict or interference is dealt with by the referee. The referee may also take away points or games due to improper etiquette regarding conduct or rules. The referee is also usually responsible for the scoring of games. Three referees are usually used in professional tournaments. The Central referee has responsibility to call the score and make decisions with the two side referees.

Scoring system

[edit]Point-a-Rally to 11

[edit]Games are played according to point-a-rally scoring (PARS) to 11 points. PARS is almost universally preferred by the game's top professionals and is the current official scoring system for all levels of professional squash tournaments. In PARS, the winner of a rally receives a point, regardless of whether they were the server or returner. Games are played to 11 and must be won by two points. That is, if the score reaches 10–10, play continues until one player wins by two points. Competition matches are usually played to "best-of-five" games (i.e., the first player to win three games).

Squash can also be played with different scoring systems, such as PARS to 15, traditional English or Hand-in-Hand-Out (HiHo) scoring to 9, or RAM scoring (see below). Players often experience PARS and Hi-Ho as requiring different tactics and player attributes.

Other scoring systems

[edit]Point-a-Rally to 15

[edit]Point-a-rally scoring to 15 was used for the World Championships between 1989 and 2003. PARS to 15, with the tiebreak being two clear points (as per standard PARS) from 14–14, was used in many amateur leagues because PARS to 11 was considered too short.[15] This system fell out of favor in 2004 when the Professional Squash Association (PSA) decided to switch to PARS to 11. Games were considered to last too long and the winner would usually be the fitter player, not necessarily the better player.[16]

English/Hand-In-Hand-Out to 9

[edit]Known as English or hand-in-hand-out scoring, under this system, if the server wins a rally, they receive a point, while if the returner wins rally, only the service changes (i.e., the ball goes "hand-out") and no point is given. The first player to reach nine points wins the game. However, if the score reaches 8–8, the player who was first to reach eight decides whether the game will be played to nine, as before (called "set one"), or to 10 (called "set two"). This scoring system was formerly preferred in Britain, and also among countries with traditional British ties, such as Australia, Canada, Pakistan, South Africa, India and Sri Lanka.

RAM

[edit]The RAM scoring system is a proposed new scoring system created by former World Champion, Ramy Ashour and co-founded by Osama Khalifa. This consists of playing a best of five games. Each game is three minutes long; however, this only refers to the three minutes in play. The 'downtime' in between the end of a rally and a serve is not counted. Once the time is up, the clock stops, and the leading player needs to win a final point. If the player who is behind wins the point the game continues until the trailing player catches up and wins one more point than the initially leading player.

For example, Player one is leading 5–3 and the clock stops. Player two wins the next two points and the score is 5–5. Whoever wins the next point wins the game. This is called sudden death. If the score is 0–0 when the clock stops the clock is reset and the game restarts. For Let Calls the clock reverts to the start time of that point. Further rules include that there must be a referee and a time keeper to make this match official. Players have two minutes of rest between games, and all other standard PSA and WSF rules apply.[17]

Transition from English/HiHo to PARS 11

[edit]In 2004, the Professional Squash Association (PSA) decided to switch to PARS 11. This decision was ratified in 2009 when the World Squash Federation confirmed the switch to the PARS 11 scoring system.[18] Since that time, almost all professional and league games have been played according to PARS to 11. One of the reasons for switching to PARS was that long, taxing matches became less frequent and promoters could more easily predict match and session length. Gawain Briars, who served as the Executive Director of the Professional Squash Association when the body decided to switch to PARS in 2004 hoped that PARS would make the "professional game more exciting to watch, [and] then more people will become involved in the game and our chances of Olympic entry may be enhanced."[19]

One of the problems with English or Hi-Ho scoring is that games often last longer as players continually win service before losing service to the other player without the score being affected. Consequently, the winner is more often than not the fitter athlete. Moreover, English or Hi-Ho scoring can encourage players to play defensively with the aim of wearing down one's opponent before winning by virtue of one's fitness. Such exhausting, defensive play can affect player's prospects in knock-out tournaments and does not make for riveting TV. In English or Hi-Ho, one player might win by 9–0 despite the opponent having repeatedly won service, but without converting that service into actual points.

For the World Championships: HiHo to 9 was used until 1988; PARS to 15 from 1989 to 2003; and PARS to 11 from 2004. For the British Open: HiHo to 9 was used until 1994; PARS to 15 from 1995 to 2003; and PARS to 11 from 2004.[20]

The WSF's decision to switch to PARS 11 proved controversial in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth where games were usually played according to English or Hi-Ho. When the Veterans Squash Rackets Club of Great Britain surveyed their members in 2012, they found that 80% of their members were against switching from HiHo to PARS.[21] President Philip Ayton argued that PARS would "kill the essence of the game."[21] Ayton was particularly concerned that the "great comebacks" that characterised English or Hi-Ho when "the player who is down in a game can still attack when in hand serving"[21] would disappear as PARS fostered an "ultra-defensive attitude, because every rally counts the same."[21]

Jahangir Khan has countered that PARS actually made the game far more attacking, but diminished the psychological aspect of the game: "With the nine points scoring system, matches were more mental and physical and could go longer, but now with the 11-point system, every rally counts, and even if you go behind you can still recover. That makes it a lot more attacking." Maj Madan, one of the game's top referees, similarly stated that PARS had "destroyed the fitness element and, more importantly, the cerebral magic of the…game."[22] His comments were unearthed when an email chain of referees discussing the problem of shorter and shorter squash matches was leaked in 2011.

Contribution to health

[edit]Squash provides an excellent cardiovascular workout. Players can expend approximately 600–1,000 food calories (3,000–4,000 kJ) every hour playing squash, according to English or Hi-Ho scoring.[23] The sport also provides a good upper- and lower-body workout by exercising both the legs in running around the court and the arms and torso in swinging the racket. In 2003, Forbes rated squash as the number-one healthiest sport to play.[23] However, one study has implicated squash as a cause of possible fatal cardiac arrhythmia and argued that squash is an inappropriate form of exercise for older men with heart disease.[24]

Around the world

[edit]| Squash |

|---|

As of November 2019, there were players from eighteen countries in the top fifty of the men's world rankings, with Egypt dominating with fifteen players, six of whom were in the top ten, including ranks one through four.[25] Similarly, the women's world rankings featured players from sixteen countries, again led by Egypt taking thirteen spots of the top fifty, whilst holding spots one through four in the world.[26]

The men's and women's Professional Squash Association tour, men's rankings and women's rankings are run by the Professional Squash Association (PSA).

The Professional Squash Tour is a tour based in the United States.[27]

Inclusion in multi-sport events

[edit]Squash has been featured regularly at the multi-sport events of the Commonwealth Games and Asian Games since 1998. Squash is also a regular sport at the Pan American Games since 1995. Squash players and associations have lobbied for many years for the sport to be accepted into the Olympic Games. Squash narrowly missed being instated for the 2012 London Games and the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Games (missed out again as the IOC assembly decided to add golf and rugby sevens to the Olympic programme).[28] Squash also was not selected as an event in the 2020 Olympic Games.[29] At the 125th IOC Session in Buenos Aires, the IOC voted for Wrestling instead of Squash or Baseball/Softball. The usual reason cited for the failure of the sport to be adopted for Olympic competition is that it is difficult for spectators to follow the action, especially via television. Previous world number one Peter Nicol stated that he believed squash had a "very realistic chance" of being added to the list of Olympic sports for the 2016 Olympic Games,[30] but it ultimately lost out to golf and rugby sevens. Squash has been part of the World Games since 1997.

Squash was accepted as a demonstration sport for the 2018 Summer Youth Olympics.[31] The World Squash Federation had hoped that this inclusion would create a strong bid for a potential inclusion at the 2024 Summer Olympics.[32]

Although not included in the 2024 Summer Olympics, squash received approval from the International Olympic Committee for inclusion in the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, on 16 October 2023.[33]

Major tournaments

[edit]- World Open Championship

- World Tour Finals

- World Team Championships

- British Open

- Tournament of Champions

- US Open

- Hong Kong Open

- Qatar Classic

- Windy City Open

- El Gouna International

- Summer Olympics

- World Games

- Commonwealth Games

- Asian Games

Players, records and rankings

[edit]

The (British) Squash Rackets Association (now known as England Squash) conducted its first British Open championship for men in December 1930, using a "challenge" system. Charles Read was designated champion in 1930, but he was beaten in home and away matches by Don Butcher, who was then recorded as the champion for 1931. The championship continues to this day, but it has been conducted with a "knockout" format since 1947.

The women's championship started in 1921, and it has been dominated by relatively few players:[34] Joyce Cave, Nancy Cave, Cecily Fenwick (England) in the 1920s; Margot Lumb and Susan Noel (England) in the 1930s; Janet Morgan (England) in the 1950s; Heather McKay (Australia) in the 1960s and 1970s; Vicki Cardwell (Australia) and Susan Devoy (New Zealand) in the 1980s; Michelle Martin and Sarah Fitz-Gerald (Australia) in the 1990s; and Nicol David (Malaysia) in the 2000s.

The Men's British Open has similarly been dominated by relatively few players:[34] F. D. Amr Bey (Egypt) in the 1930s; Mahmoud Karim (Egypt) in the 1940s; brothers Hashim Khan and Azam Khan (Pakistan) in the 1950s and 1960s; Jonah Barrington (Great Britain and Ireland) and Geoff Hunt (Australia) in the 1960s and 1970s; Jahangir Khan (Pakistan) 1980s; Jansher Khan (Pakistan) in the 1990s; and more recently, David Palmer and Nick Matthew.

The World Open professional championship was inaugurated in 1976 and serves as the main competition today. Jansher Khan holds the record of winning eight World titles followed by Jahangir Khan with six, Geoff Hunt & Amr Shabana four, Nick Matthew & Ramy Ashour three. The women's record is held by Nicol David with eight wins followed by Sarah Fitzgerald five, Susan Devoy four, and Michelle Martin three.

Heather McKay remained undefeated in competitive matches for 19 years (between 1962 and 1981) and won sixteen consecutive British Open titles between 1962 and 1977.[35]

Current rankings

[edit]The Professional Squash Association (PSA) publishes monthly rankings of professional players:

Men's

[edit]| PSA Men's World Rankings, of the 24th of June 2024[36] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Player | Points | Move† | |

| 1 | 2,322 | |||

| 2 | 1,589 | |||

| 3 | 1,531 | |||

| 4 | 1,395 | |||

| 5 | 889 | |||

| 6 | 887 | |||

| 7 | 812 | |||

| 8 | 744 | |||

| 9 | 738 | |||

| 10 | 577 | |||

Women's

[edit]| PSA Women's World Rankings, of the 24th of June 2024[37] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Player | Average | Move† | |

| 1 | 2,192 | |||

| 2 | 1,820 | |||

| 3 | 1,476 | |||

| 4 | 903 | |||

| 5 | 893 | |||

| 6 | 870 | |||

| 7 | 855 | |||

| 8 | 821 | |||

| 9 | 610 | |||

| 10 | 570 | |||

Current champions

[edit]| Competition | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edition | Title holder | Edition | Title holder | |

| World Championship | 2023-24 | 2023-24 | ||

| WSF World Team Championships | 2023 | 2022 | ||

| World Games | 2022 | 2022 | ||

| WSF World Junior Championships | 2023 | 2023 | ||

| WSF World Junior Team Championships | 2022 | 2023 | ||

| World University | 2022 | 2022 | ||

| World Masters (Over 35) | 2022 | 2022 | ||

See also

[edit]- Basque pelota

- British Open Squash Championships

- Hardball squash

- The Howe Cup

- List of US Intercollegiate squash champions

- List of PSA number 1 ranked players

- List of WSA number 1 ranked players

- List of squash players

- Longest squash match records

- PSA World Tour records

- PSA World Tour

- Rackets (also called "hard rackets", "prison tennis")

- Racquetball

- Squash tennis

- Table squash

- US Junior Open squash championship

- World Championship

- World Squash Federation

- World Team Squash Championships

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2020-08-23. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Squash confirmed for LA28 Olympic Games".

- ^ a b c Zug, James. "History of Squash". US Squash. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ "From prison rackets to squash racquets". 26 June 2002. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Grays of Cambridge: History" Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine – makers of rackets and founded in 1855 by Henry John Gray, the Champion rackets Player of England. "In those days, the rackets were made from one piece English ash, with a suede leather grip and natural gut. ... The 1980s witnessed a period of re-structuring and consolidation. The Cambridge rackets factory was forced to close in face of the move to graphite rackets, and production was moved to the Far East."

- ^ "Squash Balls". Squashplayer.co.uk. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ "Sports, For Parents, Teachers and Coaches, National Eye Institute [NEI]". Nei.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ "Squash Court Construction: "How to build a Court?" – ASB SquashCourt". asbsquash.com. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ "Squash: The Definitive Guide (and How You Can Start to Play Today)". BossSquash. 14 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Agility Training: Improving Sporting Reaction Times". Pponline.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ "Squash : Nick Matthew v James Wilstrop : 2011 Delaware Investments U.S. Squash Open". YouTube. 12 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ "Squash : Nick Matthew v James Wilstrop : 2011 Delaware Investments U.S. Open Squash". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Strategies, Jonathon Power Exposed DVD 2.

- ^ Commentary by Jonathon Power and Martin Heath, TOC, 2005

- ^ "PAR scoring equals less squash".

- ^ "Frequently asked questions on squash – general squash tips". squashclub.org.

- ^ "RAM Scoring System". Archived from the original on 2019-05-18. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ "Squash: New Scoring System | IWGA".

- ^ "New Scoring System". www.squashplayer.co.uk. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ "Number of rallies in squash games depending on scoring method". Archived from the original on 2019-07-17. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ a b c d Gilmour, Rod (13 June 2012). "Squash scoring changes will 'kill essence of the game', say top British veterans". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ "Will's World The Referees' Call | Squash Magazine". squashmagazine.ussquash.com. August 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Santelmann, N. 2003. Ten Healthiest Sports". Forbes.com. 30 September 2003. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Heart rate and metabolic response to competitive squash in veteran players: identification of risk factors for sudden cardiac death", European Heart Journal, Volume 10, Number 11, Pp. 1029–1035, abstract. Additionally, squash players are prone to injuries during the game and should do necessary stretching before and after.

- ^ "PSA World Tour Rankings". psaworldtour.com. 26 November 2019. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "PSA World Tour Rankings". psaworldtour.com. 26 November 2019. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Professional Squash Tour". Prosquashtour.net. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ "Golf & rugby voted into Olympics". BBC.co.uk. 9 October 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ "Squash Leads on 'Innovation' in Bid Presentation". World Squash Federation. 19 December 2012.

- ^ Slater, Matt (23 March 2007). "Squash 'deserves Olympic place', BBC article". BBC News. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Buenos Aires 2018 take Youth Olympic Games to the next level with Squash". World Squash Federation. 6 July 2017. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Squash Favourite for 2024 Olympic Games inclusion". squash.org.au. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "International Olympic Committee approves cricket and four other sports for 2028 Games in Los Angeles". Sky Sports. 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Championship records". Allam British Open Squash.

- ^ "Heather McKay". Squash NSW. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ "Current PSA World Rankings". PSA World Tour, Inc.

- ^ "Current PSA World Rankings". PSA World Tour, Inc.

General sources

[edit]- Bellamy, Rex (1978). The Story of Squash. Cassell Ltd, London. ISBN 0-304-29766-6.

- Palmer, Michael (1984). Guinness Book of Squash. Guinness Superlatives Ltd, London. ISBN 0-85112-270-1.

- "Rules of Squash; effective 5 December 2020 and amended 27 November 2021". World Squash Federation. 9 June 2010.

- "squash a glimpse of its colorful history". winningsquash.com. winning squash. 17 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Satterthwaite, Frank (1979). The three-wall nick and other angles: a squash autobiography. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 0-03-016666-7.

- Zug, James; Plimpton, George (2003). Squash: a history of the game. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-2990-8.