Climate change in Germany

Climate change is leading to long-term impacts on agriculture in Germany, more intense heatwaves and coldwaves, flash and coastal flooding, and reduced water availability. Debates over how to address these long-term challenges caused by climate change have also sparked changes in the energy sector and in mitigation strategies. Germany's energiewende ("energy transition") has been a significant political issue in German politics that has made coalition talks difficult for Angela Merkel's CDU.[1]

Despite massive investments in renewable energy, Germany has struggled to reduce coal usage. The country remains Europe's largest importer of coal and produces the 2nd most coal in the European Union behind Poland, about 1% of the global total. Germany phased out nuclear power in 2023,[2] and plans to retire existing coal power plants by 2030.[3]

German climate change policies started to be developed in around 1987 and have historically included consistent goal setting for emissions reductions (mitigation), promotion of renewable energy, energy efficiency standards, market based approaches to climate change, and voluntary agreements with industry. In 2021, the Federal Constitutional Court issued a landmark climate change ruling, which ordered the government to set clearer targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[4]

Greenhouse gas emissions

[edit]Germany aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045. It has set provisional objectives of reducing emissions by at least 65 percent by 2030 and 88 percent by 2040 compared to 1990 levels.[5]

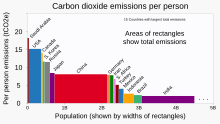

Greenhouse gas emissions in Germany have decreased since 1990, falling from 1,242 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents in 1990 to 762 million tonnes in 2021. Following a period of stagnation, emissions have decreased significantly from 2017 to 2021, owing primarily to higher emissions trading certificate rates and the growth of green energy.[6] The federal environment agency UBA reported in March 2022 that Germany's greenhouse gas emissions increased by 4.5% in 2021 compared to 2020.[7]

As of 2021[update] Germany is the 6th heaviest cumulative emitter at about 100 Gt.[8] In 2016, Germany's government committed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80% to 95% by 2050.[9]

In 2020, a group of youths aged 15 and 32 filed a suit arguing that the Federal Climate Protection Act, in force since 18 December 2019, inadequately protected their rights to a humane future for being to weak to contain the climate crisis.[10] Among the complainants are German youths living on islands that are experiencing more frequent flooding.[11]

On 29 April 2021, German Constitutional Court issued a landmark climate change ruling that the government must set clearer targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[4] The court called the current government provisions "incompatible with fundamental rights" since it placed the burden of major emissions reduction onto future generations. The court ruling gave the government until the end of 2022 to set clearer targets for reducing greenhouse emissions starting in 2031.[4]

The suit filed by the youths form part of a broader movement of youth activists around the world using street and online protests and lawsuits to pressure governments to act against climate change.[11]

In August 2022, Germany's Chancellor Olaf Scholz has met Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to sign a deal to establish hydrogen supply chains with Canada.[12] Germany hopes to be free of Russian gas by the middle of 2024.[13]

Methane emissions

[edit]From coal mining

[edit]A report in 2024 by the energy think tank Ember has brought attention to potential underreporting in Germany's coal mine methane (CMM) emissions. The report suggests that the actual emissions could be significantly higher than the figures officially reported by Germany. In 2022, Germany, which mined 131 million tonnes of lignite coal, amounting to 44% of the European Union's (EU) production, reported only 1,390 tonnes of CMM emissions. This figure is in stark contrast to independent studies, which imply that the real emissions could be 28 to 220 times the reported amount, adding up to an estimated 300,000 tonnes of methane annually. Ember's own analysis estimates Germany’s annual CMM emissions to be approximately 256,000 tonnes, a number which is supported by satellite data showing methane concentrations as high as 34 parts per billion (ppb) over certain mining areas. The report underscores the need for Germany to update its emission reporting practices, especially in light of the upcoming EU Methane Regulation.[14]

Impacts on the natural environment

[edit]Temperature and weather changes

[edit]Extreme weather events

[edit]

The North Sea provinces of Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony have a high vulnerability to storm surges and high-impact river flooding. The Baltic province of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania is less vulnerable to storm surges, but at higher risk to loss of biodiversity and loss of topsoil and erosion.[18]

Impacts on people

[edit]Economic impacts

[edit]As a highly industrial, urbanized economy with a relatively short coastline compared to other major economies, the impacts of climate change on Germany are more narrowly focused than other major economies. Germany's traditional industrial regions are typically the most vulnerable to climate change. These are mostly located in the provinces of North Rhine-Westphalia, Saarland, Rhineland-Palatinate, Thuringia, Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein and the free cities of Bremen and Hamburg.[18]

The Rhineland is historically a heavily industrial and population-dense area which includes the states of North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland Palatinate, and Saarland. This region is rich in iron and coal deposits and supports one of Europe's largest coal industries. In the past, sulfuric acid emissions from Rhineland coal plants contributed to acid rain, damaging forests in other regions like Hesse, Thuringia, and Saxony.

Other significant problems for the Rhineland related to its high level of industrialization include the destruction of infrastructure from extreme weather events, loss of water for industrial purposes, and fluctuation of the ground water level. Since these problems are related to its level of industrialization, cities within other regions are also sensitive to these challenges including Munich and Bremen.

Agriculture

[edit]Warming in Germany has affected some parts of the German agricultural industry. In particular, warming since at least 1988 in the Southwest wine-growing regions has caused a decline in the output of ice wine, a product particularly vulnerable to warming. In 2019, almost no ice wine was produced due to lack of sufficiently cold days.[19]

A key reason why the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania is particularly vulnerable to climate change among northern provinces is that it is a relatively poor region of Germany with a large agricultural sector.[20]

Health impacts

[edit]Many Rhineland provinces and regions are heavily built-up, creating a heat island effect. In addition, urban areas are rapidly aging along with the rest of Germany. This increases the severity and frequency of heatwaves which can be dangerous for vulnerable populations such as the elderly.[18]

Flooding

[edit]A November 2020 simulation published in the KN Journal of Cartography and Geographic Information found that using Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) scenarios 4.5 and 8.5, between 5477 and 626,880 people would be affected by flooding due to sea-level rise in Northern Germany. The bulk of the difference stems from whether the dikes will breach or not.[21]

Mitigation and adaptation

[edit]Mitigation approaches

[edit]Renewable energy

[edit]Germany has created multiple policies meant to encourage the use of renewable energy sources, such as the Electricity Feed-In Act and Renewable Energy Sources Act.[22] The 1991 Electricity Feed-In Act stipulated that utilities purchase subsidized renewable electricity, which effectively cost 90% of the retail price which henceforth made the development of wind, biomass, and hydroelectric power economically viable.[22] It is estimated that the Electricity Feed-In Act is responsible for a 42x increase in wind power from 1990 to 1998.[23]

Despite initial success, due to shifts in the electricity market, the Electricity Feed-In Act was no longer as effective by the end of the decade, and was later strengthened by the 2000 Renewable Energy Sources Act. This act guaranteed the price of renewable energy for twenty years by setting feed-in prices, and spread the costs of wind power subsidies across consumers of all energy sources.[22]

Mitigation efforts are being undertaken at all levels of government. Federal-level efforts are being carried out by the Umweltbundesamt (UBA), Germany's primary environmental protection agency, serving a similar function to the US' EPA.[24] The UBA's primary role is to make environmental risk assessments and deliver policy recommendations to the Ministry of the Environment. The agency is also in charge of enforcing environmental protection laws including in the approval process for new pharmaceuticals and pesticides and CO2 trading.

In some parts of Germany a phase-out of petrol and diesel vehicles is planned by 2030.[25]

Transport

[edit]In May 2022, some countries in the European Union strongly reduced the price for traveling on Public transport, among others, because this is a relatively climate-friendly mode of transportation: Germany, Austria, Ireland (country), Italy. Germany reduced the price to 9 euro. In some cities the price was cut by more than 90%. The national rail company of Germany committed to increase the number of trains and extend lines to new destinations. The use of trains significantly increased so that "ticket websites have crashed upon the release of the tickets."[26][27]

Adaptation approaches

[edit]In 2008, the German Federal Cabinet adopted the 'German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change'[28] that sets out a framework for adaptation in Germany. Priorities are to collaborate with the Federal States of Germany in assessing the risks of climate change, identifying action areas and defining appropriate goals and measures. In 2011, the Federal Cabinet adopted the 'Adaptation Action Plan'[29] that is accompanied by other items such as research programs, adaptation assessments and systematic observations.[30]

Policies and legislation to achieve mitigation

[edit]Paris Agreement

[edit]The Paris agreement is a legally binding international agreement, its main goal is to limit global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels.[31] The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC's) are the plans to fight climate change adapted for each country.[32] Every party in the agreement has different targets based on its own historical climate records and country's circumstances and all the targets for each country are stated in their NDC.[33] In the case of member countries of the European Union the goals are very similar and the European Union work with a common strategy within the Paris agreement.[34]

Goal setting

[edit]The third report as produced by the Climate Enquête Commission, released in 1990 titled "Protecting the Earth," called for Germany to make a 30% reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from 1987 levels by 2005 and an 80% decrease in emissions by 2050.[35] After the report was released, the German federal government adopted the recommended 25-30% emissions reduction goal by 2005.[35] Later reduction goals include Germany's pledge to reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 21% from 1990 to 2012 as part of the EU's collective 8% reduction from the Kyoto Protocol, and the 2005 target of reducing GHG emissions by 40% from 1990 to 2020.[22] The adoption of these national targets have motivated the German government to adopt different policies to meet these goals.

In February 2022 the government of Germany begun to advance a new goal of 100% renewable electricity by 2030. The plan is to use solar and wind energy.[36]

Voluntary agreements with industry

[edit]In addition to nationally adopted emission reduction goals, private industry has also made agreements with the government to reduce their emissions.[37] In 1995, German industry published a voluntary declaration of their reduction goals, which was later revised in 1996.[23] In November 2000, a report was released that indicated multiple sectors of German industry were on track to exceed their targets in half of the originally stipulated time.[23] Encouraged by this success, industry published another revised declaration which aimed to reduce their total GHG emissions 35% by 2005.[23]

"Wall Fall" effect

[edit]A major driver of Germany's GHG emissions reductions was a result of German reunification in 1990, whose economic revitalization and other policies are credited with reducing 112.9 megatons of CO2/year from 1990 to 2010.[38] The environmental benefits of reunification policies were largely co-benefits from modernization measures such as improving energy efficiency standards and the creation of a private coal mining industry.[23]

EU energy plan 2008

[edit]In the end of 2008 the parliament of the EU approved the climate and energy plan including:[39]

- - 20% emission cut of climate gases from 1990 to 2020

- - 20% increase in the share of renewable energy from 1990 to 2020

- - 20% increase of the energy efficiency from 1990 to 2020.

Dedicated Federal Ministries

[edit]Mitigation efforts are being undertaken at all levels of government. Federal-level efforts are being carried out by the Umweltbundesamt (UBA), Germany's primary environmental protection agency, serving a similar function to the US' EPA.[24] The UBA's primary role is to make environmental risk assessments and deliver policy recommendations to the Ministry of the Environment. The agency is also in charge of enforcing environmental protection laws including in the approval process for new pharmaceuticals and pesticides and CO2 trading.

2019 climate change act

[edit]The Federal Cabinet initiated the climate change act in October 2019 to make climate targets legally binding. It will include how much CO2 each sector is allowed to emit per year. It is quantified and verifiable sectoral targets for every year from 2020 to 2030. The Federal Environment Agency and an independent council of experts will be responsible for monitoring.[40]

Litigation

[edit]In 2021, Germany's supreme constitutional court ruled in Neubauer v. Germany that the government's climate protection measures are insufficient to protect future generations and that the government had until the end of 2022 to improve its Climate Protection Act.[41]

In 2023, the Berlin-Brandenburg Higher Administrative Court said the government's action on transport and housing fell short under a law setting upper limits for carbon emissions for individual sectors. Under the ruling, Berlin must present emergency programmes to bring its policy on transport and housing back in line with the current Climate Protection Act from 2024 to 2030.[42]International cooperation

[edit]

Germany has taken steps to address climate change since the mid-1980s, starting with their participation in the international negotiations of the Montreal Protocol which was signed in 1987.[23]

Society and culture

[edit]Public awareness

[edit]The Montreal Protocol in 1987, alongside the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986, acted as focusing events for German public and subsequently pushed the environment to the top of the policy agenda. As a result, the German government under Chancellor Helmut Kohl established the Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation, and Nuclear Safety (Bundesministrium fuer Umwelt, Natureschutz, und Reaktorsicherheit, BMU) in 1986 and the subcommittee the Enquête Commission on Preventive Measures to Protect the Earth's Atmosphere (Climate Enquête Commission) in 1987.[23] The role of these committees was to research issues relating to the ozone depletion problem as well as the climate change problem, facilitate parliamentary debate, and produce reports for policymakers to create well informed programs.

The reports produced by the Climate Enquête Commission created the beginning framework of German climate change policies, which have historically included consistent goal setting for emissions reductions, promotion of renewable energy, energy efficiency standards, market based approaches to climate change, and voluntary agreements with industry

Activism

[edit]Germany hosted the COP23 meeting in Bonn in 2017 to which the German delegation traveled in a carbon-neutral train to demonstrate commitment to carbon neutrality.[43]

It was calculated in 2021 that to give the world a 50% chance of avoiding a temperature rise of 2 degrees or more Germany should increase its climate commitments by 25%.[44] For a 95% chance it should increase the commitments by 79%. For a 50% chance of staying below 1.5 degrees Germany should increase its commitments by 120%.[44]: Table 1

Yiannis Kountouris conducted a study, using the German Socioeconomic Panel, that centered itself around the question of if a county that's been under authoritarian rule cares less about climate change than a democracy. Kountouris used East and West Germany, as well as East and West Berlin when asking the former residents of these two governments. It turns out those who cared less about climate change did in fact live in East Germany, while those who cared more about the climate, lived in Western Germany. Another found result was residents from the east who were exposed to freedom took time to acclimate to the understanding of climate change. It didn't happen over night.[45]

See also

[edit]- European Green Deal

- Climate change in the European Union

- German Climate Action Plan 2050

- Plug-in electric vehicles in Germany

References

[edit]- ^ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "German election: Preliminary coalition talks collapse after FDP walks out | News | DW | 19.11.2017". DW.COM. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ "Germany has shut down its last three nuclear power plants, and some climate scientists are aghast". NBC News. 18 April 2023.

- ^ "Germany's Habeck Hopeful on Switching Off Coal Plants". Bloomberg. 3 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Treisman, Rachel (29 April 2021). "German Court Orders Revisions To Climate Law, Citing 'Major Burdens' On Youth". NPR. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ "Climate Change Act: climate neutrality by 2045". Webseite der Bundesregierung | Startseite (in German). Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ Wilke, Sibylle (27 February 2017). "Indicator: Greenhouse gas emissions". Umweltbundesamt. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Germany's Carbon Emissions Rise in Setback for Climate Goals". Bloomberg.com. 15 March 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Analysis: Which countries are historically responsible for climate change?". Carbon Brief. 5 October 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ German coalition agrees to cut carbon emissions up to 95% by 2050 The Guardian 14.11.2016

- ^ "How youth climate court cases became a global trend". Climate Home News. 30 April 2021. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ a b Rall, Katharina (29 April 2021). "Germany's Top Court Finds Country's Climate Law Violates Rights". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Rinke, Andreas; Scherer, Steve (22 August 2022). "Germany, Canada to boost energy, mineral ties as they decarbonize". Reuters. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ O'Donnell, John (10 May 2022). "Exclusive: Germany prepares crisis plan for abrupt end to Russian gas". Reuters. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Updating Germany's coal mine methane emission factor". Ember. 10 April 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Hausfather, Zeke; Peters, Glen (29 January 2020). "Emissions – the 'business as usual' story is misleading". Nature. 577 (7792): 618–20. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..618H. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00177-3. PMID 31996825.

- ^ Schuur, Edward A.G.; Abbott, Benjamin W.; Commane, Roisin; Ernakovich, Jessica; Euskirchen, Eugenie; Hugelius, Gustaf; Grosse, Guido; Jones, Miriam; Koven, Charlie; Leshyk, Victor; Lawrence, David; Loranty, Michael M.; Mauritz, Marguerite; Olefeldt, David; Natali, Susan; Rodenhizer, Heidi; Salmon, Verity; Schädel, Christina; Strauss, Jens; Treat, Claire; Turetsky, Merritt (2022). "Permafrost and Climate Change: Carbon Cycle Feedbacks From the Warming Arctic". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 47: 343–371. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011847.

Medium-range estimates of Arctic carbon emissions could result from moderate climate emission mitigation policies that keep global warming below 3°C (e.g., RCP4.5). This global warming level most closely matches country emissions reduction pledges made for the Paris Climate Agreement...

- ^ Phiddian, Ellen (5 April 2022). "Explainer: IPCC Scenarios". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 20 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

"The IPCC doesn't make projections about which of these scenarios is more likely, but other researchers and modellers can. The Australian Academy of Science, for instance, released a report last year stating that our current emissions trajectory had us headed for a 3°C warmer world, roughly in line with the middle scenario. Climate Action Tracker predicts 2.5 to 2.9°C of warming based on current policies and action, with pledges and government agreements taking this to 2.1°C.

- ^ a b c Rannow, Sven; Loibl, Wolfgang; Greiving, Stefan; Gruehn, Dietwald; Meyer, Burghard C. (30 December 2010). "Potential impacts of climate change in Germany—Identifying regional priorities for adaptation activities in spatial planning". Landscape and Urban Planning. Climate Change and Spatial Planning. 98 (3): 160–171. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.08.017.

- ^ Schuetze, Christopher (4 March 2020). "Warming Winter (Almost) Cuts Off a Sweet Wine Tradition in Germany". The New York Times.

- ^ nzenkand (26 August 2010). "Mecklenburg-West Pomerania". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ Schuldt, Caroline; Schiewe, Jochen; Kröger, Johannes (1 December 2020). "Sea-Level Rise in Northern Germany: A GIS-Based Simulation and Visualization". KN - Journal of Cartography and Geographic Information. 70 (4): 145–154. doi:10.1007/s42489-020-00059-8. ISSN 2524-4965.

- ^ a b c d Karapin, Roger (2012). "Climate Policy Outcomes in Germany: Environmental Performance and Environmental Damage in Eleven Policy Areas". German Politics & Society. 30 (3 (104)): 1–34. doi:10.3167/gps.2012.300301. JSTOR 23744579.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rie, Watanabe; Mezb, Lutz (2003). "The Development of Climate Change Policy in Germany". International Review for Environmental Strategies. 5 (1).

- ^ a b Meunier, Corinne (6 September 2013). "About us". Umweltbundesamt. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ Böll, Sven (8 October 2016). "Ab 2030: Bundesländer wollen Benzin- und Dieselautos verbieten". Spiegel Online.

- ^ Klinkenberg, Abby. "PUBLIC TRANSIT PRICES SLASHED ACROSS EUROPE". Fair Planet. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Andrei, Mihai. "Germany slashes public transit fares to reduce fuel usage". ZME Science. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ "German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Adaptation Action Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Germany — Climate-ADAPT". climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ United Nations, United Nations Climate Change. "The Paris Agreement". unfccc.int. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "NDC spotlight". UNFCCC. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "Nationally Determined Contributions". unfccc. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "The update of the nationally determined contribution of Germany" (PDF). UNFCCC. 17 December 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ a b EBERLEIN, BURKARD; DOERN, G. BRUCE, eds. (2009). "Governing the Energy Challenge". Governing the Energy Challenge: Canada and Germany in a Multilevel Regional and Global Context. University of Toronto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442697485. ISBN 9780802093059. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442697485.

- ^ Wacket, Markus; Szymanska, Zuzanna; Murray, Miranda; Donovan, Kirsten (28 February 2022). "Germany aims to get 100% of energy from renewable sources by 2035". Reuters. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Lynn, Price (1 June 2005). "Voluntary Agreements for Energy Efficiency or GHG Emissions Reduction in Industry: An Assessment of Programs Around the World".

- ^ Karapin, Roger (2012). "Explaining Success and Failure in Climate Policies: Developing Theory through German Case Studies". Comparative Politics. 45 (1): 46–68. doi:10.5129/001041512802822879. JSTOR 41714171. S2CID 15459719.

- ^ Ilmastonmuutos otettiin yhä vakavammin [permanent dead link]; Yle 30.12.2008 (in Finnish)

- ^ Minister Schulze: Climate action becomes law! Archived 1 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine 9.10.2019

- ^ Connolly, Kate (29 April 2021). "'Historic' German ruling says climate goals not tough enough". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ "German court finds govt climate policy unlawful, orders emergency action". Reuters. 30 November 2023.

- ^ "UN Climate Change Conference: German delegation to take the "Train to Bonn" - BMUB-Pressreport". bmub.bund.de (in German). Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ a b R. Liu, Peiran; E. Raftery, Adrian (9 February 2021). "Country-based rate of emissions reductions should increase by 80% beyond nationally determined contributions to meet the 2 °C target". Communications Earth & Environment. 2 (1): 29. Bibcode:2021ComEE...2...29L. doi:10.1038/s43247-021-00097-8. PMC 8064561. PMID 33899003.

- ^ Kountouris, Yiannis (1 July 2021). "Do political systems have a lasting effect on climate change concern? Evidence from Germany after reunification". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (7): 074040. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac046d. hdl:10044/1/89873.