Dhammakaya meditation

Dhammakaya meditation (also known as Sammā Arahaṃ meditation) is a method of Buddhist Meditation developed and taught by the Thai meditation teacher Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro (1885–1959).[note 1] In Thailand, it is known as Vijjā dhammakāya, which translates as 'knowledge of the dhamma-body'. The Dhammakaya Meditation method is popular in Thailand and other parts of Southeast Asia, and has been described as a revival of samatha (tranquility) meditation in Thailand.

The Dhammakaya Tradition believes the method to be the same as the original method the Buddha used to attain enlightenment, which was lost and then rediscovered by Luang Pu Sodh in the 1910s. The most important aspect of the meditation method is the focus on the center of the body, which leads to the attainment of the Dhammakāya, the Dhamma-body, found within every human being. Similar to other meditation traditions, the Dhammakaya Tradition believes the meditation technique leads to the attainment of Nirvana, and in advanced stages, can give the meditator various supernatural abilities, or abhiñña.

Dhammakaya Meditation is taught at several temples of the Tradition, and consists of a stage of samatha (tranquility) and vipassana (insight), following the structure of the Visuddhimagga, a standard fifth-century Theravāda guide about meditation. In the method, the stages are described in terms of inner bodies (Pali: kāya), but also in terms of meditative absorptions (Pali: jhānas).

Scholars have proposed several possibilities for the origin of the method, with the Yogavacara tradition as the likely source, as well as acknowledging that Luang Pu Sodh may have independently developed it through his own psychic experiences.

Dhammakaya Meditation has been the subject of considerable discussion among Buddhists as to its authenticity and efficacy, and also has been the subject of several scientific studies.

Nomenclature

[edit]Dhammakaya Meditation is also referred to as Vijja thammakai or Vijjā dhammakāya.[4][5][6] The word vijjā is derived from the Vedic Sanskrit term vidya or knowledge, while dhammakāya means "Dhamma-body". Together, it connotes 'knowledge of the Dhamma-body'.[7][5][6] The tradition itself, as for example expressed in books of Wat Phra Dhammakaya, defines Vijjā Dhammakāya as "Clear knowledge that arises from insight through the vision and knowledge of the Dhammakaya."[8]

History

[edit]Thai 19th-century reform movement

[edit]In 19th and early 20th-century Thailand, public perception of the practice of Buddhism changed. Originally, Thai people saw meditation mostly as a personal and quite esoteric practice. In response to threats of colonial powers, the Thai kings and the reformed Dhammayut fraternity attempted to modernize Buddhism. Mahayana and Tantric practices were considered "devotional and degenerate", while the orthodox Theravada tradition as the more legitimate one with closed canonical scriptures.[9]

The royal family of Thailand sought to reform Thai Buddhism with its ritualized and mystical practices, encouraging instead the direct study and adherence to the Pali canonical and commentarial texts. This was, in part, similar to the European Protestant tradition, reaching back to normative scriptures, in this case the 5th-century Visuddhimagga of Buddhaghosa. In this process, meditation tradition was devalued among monastics, as the study of scriptures was more valued. Thai temples in the Mahānikāya fraternity were forced to adjust to new reforms, including the meditation method used and taught.[10] Education in Buddhist doctrine was standardized and centralized, and some local meditation lineages such as of Ajarn Mun gradually died out.[11]

Meditation traditions responded by reforming their methods, and looking for textual support for their meditation system in the Buddhist scriptures, in an attempt to establish orthodoxy and survive. Meditation became less esoteric, as temple traditions and their local teachers adapted to this pressure for uniform orthodox meditation practice.[12]

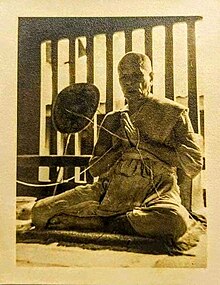

Luang Pu Sodh

[edit]

According to biographies published by Dhammakaya-related temples, the principles of Dhammakaya meditation were rediscovered by Luang Pu Sodh at Wat Botbon, in Nonthaburi Province sometime between 1915–1917.[note 2] The tradition was started by Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro in the early twentieth century.[16][17]

One night, after three hours of meditating on the mantra sammā araham,[note 3] "his mind [suddenly] became still and firmly established at the very centre of his body," and he experienced "a bright and shining sphere of Dhamma at the centre of his body, followed by new spheres, each "brighter and clearer."[18] According to Luang Pu Sodh, this was the true Dhamma-body, or Dhammakaya, the "spiritual essence of the Buddha and nibbana [which] exists as a literal reality within the human body,"[18] what became known as the attainment of the Dhammakaya,[14][22] the eternal Buddha within all beings. The dhammakaya is Nibbāna, and Nibbāna is equated with a person's true self (as opposed to the non-self).[23][note 4]

Yogavacara origins

[edit]Luang Pu Sodh's approach may have roots in the Yogavacara tradition (also known as tantric Theravāda or borān kammaṭṭhāna); not to be confused with the Yogacāra School in Mahāyāna Buddhism).[25][26][27] The Dhammakaya meditation method managed to survive the pressures to reform Buddhism in modern Thailand.[28] Its ancestry may be related to the Suk meditation system and to Wat Rajasittharam, the former residence of Somdet Suk (early 19th century), "the heir to the teaching of Ayutthaya meditation masters,"[29][note 5] and the temple where Luang Pu Sodh used to study the Suk system before he went on to develop Dhammakaya meditation.[31][32]

According to Mackenzie, Yogavacara ideas are the most likely influence on Dhammakaya meditation system, though this is not definitely proven.[17] According to Buddhist Studies scholar Catherine Newell, "there is no doubt that Dhammakaya meditation is based upon the broader Yogavacara tradition." She presents evidence of the borrowing of Luang Pu Sodh's Dhammakaya system from Somdet Suk's system of meditation.[25] She and Asian studies scholar Phibul Choompolpaisal believe a Yogavacara origin to be most likely.[25][33] If this would be the case, the tradition's meditation method would be an exoteric (openly taught) version of what initially was an esoteric tradition.[34] Thai Studies scholar Barend Jan Terwiel has argued for a connection between Dhammakaya meditation and Thai meditation practices since the Ayutthaya period (1350–1776), in which the crystal ball at the center of the body plays a key role. He bases his conclusions on depictions of Nirvana in the manuscripts of the text Traiphuum Phra Ruang. He believes that this tradition may be identified as Yogavacara.[35] Choompolpaisal lists a number of similarities between Dhammakaya meditation and Yogavacara practices from 56 anonymous Ayutthaya meditation teachers. Some of these methods focus on a similar point in the body, and feature the same objects used in visualization, that is, a Buddha image and a crystal ball. The meditative experiences which follow after visualization are also similar in nature between the 56 teachers and Dhammakaya. In both, the words dhamma sphere (duangtham) and dhammakāya are used to describe some of the experiences. Finally, the Ayutthaya teachers refer to inner bodies in some of their techniques, which have similar features to some of the inner bodies in the Dhammakāya system.[36]

An alternative theory suggests an origin in Tibetan or other forms of Mahāyāna Buddhism.[37][38][39][38] According to Mackenzie, it is possible but unlikely that someone who knew the Tibetan meditation methods met and shared that knowledge with Luang Pu Sodh in the early 1910s.[17] There are similarities between the two systems, states Mackenzie, as well as with the concepts such as chakra (tantric psycho-physical centers), "crystal sphere" and Vajra.[17] Though these commonalities are widely accepted, no proof has emerged yet of the cross-fertilization of Tibetan Buddhist practices into Dhammakaya system.[17] Crosby doubts the link, because of the two systems using different terminology.[40]

It is also "quite possible" that Luang Pu Sodh developed the Dhammakaya meditation approach through his own "psychic experiences", in Mackenzie's words,[41] or partly based on older tradition, and partly a new invention.[25]

Growth and popularisation

[edit]

After discovering the method of Dhammakaya meditation, Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro first taught it to others at Wat Bangpla, in Nakhon Pathom Province.[42] Luang Pu Sodh was given his first position as abbot at Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen, a temple that has been associated with Dhammakaya meditation ever since.

In 1931, Luang Pu Sodh set up what he called a 'meditation workshop' (Thai: โรงงานทำวิชชา, romanized: ronggan tham vicha) with meditation practitioners meditating in six-hour shifts throughout the day.[43] According to a textbook of one temple, the meditation workshop was reserved for gifted practitioners able to practice Dhammakaya meditation on a higher level.[43][22][44] The purpose of the workshop was to use meditation to study certain subjects, which included understanding the nature of the world and the universe, "to learn the truth about the worlds and the galaxies".[45]

Since Luang Pu Sodh's death in 1959, Dhammakaya meditation has been taught by his students at several major temples, including Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen, Wat Phra Dhammakaya in Pathum Thani, Wat Luang Por Sodh Dhammakayaram in Damnoen Saduak District, Ratchaburi Province, and Wat Rajorasaram in Bang Khun Thian District, Bangkok, as well as in branch centers of these temples across and outside of Thailand.[46][47][48] Of these, Wat Phra Dhammakaya and Wat Luang Por Sodh Dhammakayaram have published instruction books on Dhammakaya meditation in English. Both also offer training retreats for the public.[49][48] The method has become very popular in Thailand and other parts of Southeast Asia,[50] and has been described as a revival of samatha (tranquility) meditation in Thailand.[51]

Method

[edit]Dhammakaya meditation includes three techniques, namely concentration on breath, repetitive chanting of the mantra samma araham, and concentrating upon a bright object.[21] The types of practices, such as visualization or use of a mantra, are not unique to Dhammakaya meditation,[21] but its specific methods for practice are.[21]

Dhammakaya meditation has both samatha and vipassana stages, like other Buddhist traditions.[52] The process of concentration in Dhammakaya meditation correlates with the description of samatha meditation in the Visuddhimagga, specifically kasina meditation.[37][53][54]

Essential in Dhammakaya meditation is the "center of the body," which Luang Pu Sodh describes as being at a point two finger widths above the navel of each person.[55] The center of the body has also been described as the "end of the breath", the point in the abdomen where the breath goes back and forth.[56][57] According to the Dhammakaya tradition, the mind can only attain a higher level of insight through this center and it is where the Dhammakaya, the Dhamma-body, is located. It has the shape of a Buddha sitting within oneself.[55][54] This center is also believed to play a fundamental role in the birth and death of an individual.[54]

The samatha stage

[edit]

As is common with traditional samatha practice, the first step of Dhammakaya meditation at the samatha level is to overcome mental hindrances to concentration.[58] This enables the meditator to focus and access the meditative center.[58]

Focusing on the center

[edit]There are several techniques taught by the Dhammakaya Tradition to help focus the attention on the center of the body.[59][60][13] Practitioners visualize a mental image at the center of the body–characteristically, a crystal ball or a crystal clear Buddha image.[55] The use of crystal ball as an aid to meditation in the Dhammakaya practice has been compared with meditation on a bright object in the Visuddhimagga,[54][21][53] and the crystal ball has become a sacred symbol of the meditation tradition.[61][62] According to Buddhist studies scholar Potprecha Cholvijarn, other objects to maintain focus at the center can also be used. For instance, Wat Phra Dhammakaya has taught people in the Solomon Islands to visualize a coconut and has taught Muslims to visualize religious symbols such as a crescent moon to maintain focus at the center.[63] The goal of this practice, states Scott, is described as the attainment of samadhi or one-pointedness of mind, in which several spheres and then various inner bodies are revealed, ultimately revealing "the true self, the true mind, the Dhammakaya."[64]

Practitioners typically repeat the samma araham mantra,[65][66] then visualize a mental image of the bright crystal or light, and then move the mental image inwards through seven bases of the mind, that is:[66]

- the nostril (right for men, left for women),

- the bridge of the nose (right for men, left for women),

- the center of the head,

- the roof of the mouth,

- the center of the throat,

- the middle of the stomach at the level of the navel and

- two finger-breadths above the previous point, where they keep their attention.

In this context, the center of the body is often called the "seventh or final base",[67][68] and is called the mind's final resting place.[66] The meditator continues to repeat the mantra while shifting the focus to the sphere's center and layers of concentric spheres therein.[69][70]

This use of psycho-physical centers in the Dhammakaya meditation is similar to the chakras in the Tibetan Buddhist tantra practice, states Mackenzie.[71] However, the detailed symbolism found in the Tibetan tradition is not found in the Dhammakaya tradition.[71] In the tradition, the first six bases facilitate visualization, but are not required, as advanced meditators can directly visualize the seventh base.[71]

After the meditator has visualized the movement of a crystal ball through the bases until it rests on the seventh final base, the practitioner envisions the body as devoid of organs, blood and everything else except the crystal ball.[64]

Spheres

[edit]When the mind is concentrated at the center of the body, the pathama-magga, or dhamma sphere (duangtham), may be seen by a wholesome person, but is not seen by an unwholesome person or those who lack sufficient concentration powers, according to Dhammakaya teachings.[70] The first sighting of this "bright crystal sphere" is considered as an important first step.[70] The first stage of this path Luang Pu Sodh simply called the 'beginning of the path' (Thai: ปฐมมรรค, romanized: pathommamak).[54] The meditation teachers state that with sufficient skill, or if there is an adequate store of merit, the meditator sees this path as a "glowing sphere".[60] According to Tanabe, this state is also described as the arising of bright light at the center of the body.[72] According to Skilton and Choompolpaisal, this practice sometimes leads to the pīti state, or the temporary experience of goosebumps or other physical responses.[73]

From this arises a brighter sphere, the sila sphere, followed by an even brighter and more refined sphere of samadhi (mental concentration). According to Jayamaṅggalo, the former abbot of Wat Luang Phor Sodh Dhammakayaram, this is the first stage of absorption, from which insight meditation can be started.[70] Next comes the pañña (wisdom, insight) sphere, and then the sphere of liberation (vimutti). Finally, the "sphere of knowledge and vision of liberation" (vimutti-ñanadassana) arises – a term normally used for Arahatship, according to the Dhammakaya meditation teachings.[74]

Inner bodies

[edit]

When the practitioner concentrates further on the vimutti-ñanadassana, a series of eight inner bodies arise from this sphere, which are successively more subtle, and come in pairs, starting with "a crude human form" (panita-manussakaya).[75][60][76][note 6] Each of these bodies is preceded by several spheres of light.[78][75] The eight inner bodies begin in a form identical to the meditator, but are more refined.[79][80] After the crude human body, there arises the "refined human body" and then the "crude celestial body" and the "refined celestial body". After the meditator attains the refined celestial body, this gives way to the "crude form Brahma body". This is followed by "refined form Brahma body", "crude formless Brahma body" and "refined formless Brahma body". Once again, like previous inner bodies, these bodies have a normal and refined form.[81]

According to Mackenzie, "[t]his series of [four] bodies seems to broadly correspond to the meditative development up to the four jhanas", through them, and then the four formless meditation attainments.[82] The final four of these inner pairs are called the Dhammakayas and are equated with the four stages of enlightenment, leading to the final stage of enlightenment (arahant).[80] In between is the 'change-of-lineage' (Pali: gotrabhū) intermediary Dhammakaya state.[75][83][note 7] According to Newell, quoting Jayamaṅggalo, this state is the ninth inner body and is characterized by "the lap width, height and sphere diameter [of] 9 meters."[80] The size of the Dhammakaya bodies increase, as the meditator progresses through these intermediate stages, from a height and lap-width of 9 meters or more to 40 meters or more.[85] According to Harvey, the visualized inner bodies in Dhammakaya teachings are said to appear like Buddha-images,[note 8] followed by bodies of Noble persons, finally that of an arahant's radiant Dhammakaya form within allowing the experience of Nirvana.[86]

| Meditation state (kāya)[87][82] | English translation[87][82] | Equated with[79][88] |

|---|---|---|

| Manussakāya | Crude human body | The meditator's physical body |

| Panīta-manussakāya | Refined human body | First absorption (jhāna) |

| Dibbakāya | Crude celestial body | Second absorption (jhāna) |

| Panīta-dibbakāya | Refined celestial body | Second absorption (jhāna) |

| Rūpabrahmakāya | Crude form Brahma body | Third absorption (jhāna) |

| Panīta-rūpabrahmakāya | Refined form Brahma Body | Third absorption (jhāna) |

| Arūpabrahmakāya | Crude formless Brahma body | Fourth absorption (jhāna) |

| Panīta-arūpabrahmakāya | Refined Formless Brahma Body | Fourth absorption (jhāna) |

| Dhammakāya-gotrabhū (crude) | The Dhamma-body of crude Change-of-lineage | Traditional term for being on the brink of the first stage of enlightenment |

| Dhammakāya-gotrabhū (refined) | The Dhamma-body of refined Change-of-lineage | Traditional term for being on the brink of the first stage of enlightenment |

| Dhammakāya-sotāpatti-magga (crude) | The Dhamma-body of crude Stream-enterer | The path of Stream-enterer |

| Dhammakāya-sotāpatti-phala (refined) | The Dhamma-body of refined Stream-enterer | The fruit of Stream-enterer |

| Dhammakāya-sakadāgāmi-magga (crude) | The Dhamma-body of crude Once-returner | The path of Once-returner |

| Dhammakāya-sakadāgāmi-phala (refined) | The Dhamma-body of refined Once-returner | The fruit of Once-returner |

| Dhammakāya-anāgāmi-magga (crude) | The Dhamma-body of crude Non-returner | The path of Non-returner |

| Dhammakāya-anāgāmi-phala (refined) | The Dhamma-body of refined Non-returner | The fruit of Non-returner |

| Dhammakāya-arahatta-magga (crude) | The Dhamma-body of the crude Arahant | The path of Arahant, anupādisesa-nibbāna (Nirvana) |

| Dhammakāya-arahatta-phala (refined) | The Dhamma-body of the refined Arahant | The fruit of Arahant, anupādisesa-nibbāna (Nirvana) |

The vipassana stage

[edit]Dhammakaya meditation begins with a samatha (concentration) method with a crystal sphere as an aid to acquiring the Dhammakaya, which is believed to exist inside everybody.[52] Although some Thai scholars and meditation traditions have criticized Dhammakaya meditation as being a samatha only method, Cholvijarn states that Luang Pu Sodh did emphasize a vipassana (insight) stage, which is done by contemplating the three marks of existence of the lower mundane inner bodies.[89] The vipassana stage is where the meditator can gain insights into the truth through observation of their own physical and mental processes.[52][90] It is believed they can understand birth, death and suffering at a deeper level, when they see the literal essence of these phenomena through meditative attainment.[91] The higher knowledge and transcendental wisdom in the vipassana stage is "beyond the attainment of Dhammakaya" of the samatha stage.[92]

According to Scott, the Dhammakaya method tends to emphasize aspects of samatha meditation, rather than vipassana meditation.[53] The Dhammakaya meditation method contrasts with the other Buddhist traditions where samatha stage is considered a preliminary step to develop "one-pointedness of mind" followed by the vipassana stage that "alone brings the meditator to full and final release (Nibbāna) in the Buddhist view".[93]

The vipassana tradition of Wat Mahathat claims that Luang Pu Sodh allegedly confessed to officials at Wat Mahathat that he had been wrong to emphasize Dhammakaya meditation as Wat Mahathat's vipassana was the best method.[94][95] The Dhammakaya tradition rejects this claim, stating that Luang Pu Sodh only learned Wat Mahathat's method as a gesture of goodwill and never made such a confession.[95] Cholvijarn points to bhikkhuni Voramai Kabilsingh, who studied and taught both methods, as being an objective source of clarity to this controversy. According to her autobiographical accounts, bhikkhuni Voramai studied Dhammakaya meditation with Luang Pu Sodh and attained dhammakaya. Afterwards she went on to study Wat Mahathat's method. After completing the course, she returned to Wat Paknam and told Luang Pu Sodh she only used her outer human body to meditate with Wat Mahathat's method, in order to keep her dhammakaya during the training. Luang Pu Sodh then told her to always keep her dhammakaya.[96]

In comparing Dhammakaya meditation with other methods she practiced, bhikkhuni Voramai states that there are four types of arahants: one who has the discriminations, one who has the higher knowledges, one who has the threefold knowledges, and one who has "dry insight", meaning they are enlightened but have none of the knowledges of the first three.[97] According to bhikkhuni Voramai, Dhammakaya meditation and the Buddho method of meditation she learned with Ajahn Lee allows one to become the first three arahants, while the vipassana method taught at Wat Mahathat allows one to become enlightened quickly, but only as a "dry insight" arahant. She goes on to say that this is because the first two methods start with samatha and end in vipassana, which is required for the first three types.[98] Cholvijarn compares this to teachings of Ajahn Lee, who gives a similar description of samatha and vipassana in relation to enlightenment.[99]

Culmination

[edit]The practitioner can accomplish a purification of the mind until an end of this can be reached, that is Nirvana.[100] According to Peter Harvey, in the Dhammakaya tradition's teachings, "Nirvana is controversially seen as one's true 'Self'", with the traditional teaching of "non-Self" (Pali: anattā) interpreted as "letting go of what is not Self, and finding what truly is Self".[86]

In Dhammakaya meditation, a distinction is made between "seeing the Dhammakāya" and "being the Dhammakāya". Only the latter is equated with having attained the stages of enlightenment at a stable level. It is believed that the further practitioners progress through the successive stages of the practice, the more their mind will become more pure and refined.[101] According to Newell, as the meditator attains the higher-levels of Dhammakaya inner bodies, he reaches the final state of dhammakaya-arahatta where he may be enlightened or unenlightened. It is the enlightened who become Arahant, while the unenlightened revert to the prior state (anupadisesa nibbana), in the Dhammakaya meditation system. Success in the higher-levels of meditation is claimed to create supranormal powers such as the ability to "visit [Buddhist] heavens and hells to see the fate the deceased family members" and "visit nibbana (nirvana) to make offerings to the Buddha", states Newell.[80] According to Scott, the samatha stage of Dhammakaya includes "the fruits of supranormal powers (iddhi) and knowledge (abhiñña)", a feature that is common in other modernist interpretations of Buddhism.[93]

The attainment of the Dhammakaya (or Dhammakayas) is described by many practitioners as the state where there is the cessation of the defilements in the mind, or, in positive terms, as the true, ultimate, permanent happiness (Pali: nibbanam paramam sukham).[64] According to Scott, "more often than not, it is the understanding of Nirvana as supreme happiness that is underscored in dhammakāya practice, rather than its traditional rendering as the cessation of greed, hatred and delusion", though at times these two descriptions are combined. This positive description of Nirvana as a state of supreme happiness may have contributed to the popularity of Wat Phra Dhammakaya to new members, states Scott.[53] This view of Nirvana in the Dhammakaya meditation system is in contrast to the orthodox Theravada via negativa description of Nirvana being "not Samsāra".[102]

The Dhammakaya is considered the "purest element" and the Buddha nature which is permanent and essential.[64] This purest element has the shape of a luminous Buddha figure sitting within oneself.[23] According to Scott, the full realization of the Dhammakaya ontology has been described in the Dhammakaya tradition as Nirvana.[64] According to Newell, Dhammakaya is sometimes described in the Dhammakaya tradition as a state reached more easily and by more meditators than the state of Nirvana. A Wat Luang Pho Sodh Dhammakayaram publication states in reference to their retreat programs, quotes Newell, "Past results indicate that half of [retreat] participants can transcend to Dhammakaya and a quarter can reach visiting Nirvana." Wat Luang Pho Sodh Dhammakayaram has claimed their meditation retreats can lead to the quick attainment of Nirvana, with testimonials claiming 'visiting nirvana within two weeks', or in one case reaching Nirvana in 'just one week'."[103]

Nirvana is described by the Dhammakaya tradition as a subtle sphere (Pali: ayatana).[100][104] The "Nirvana sphere" is believed by Dhammakaya practitioners to appear as a subtle physical realm where "enlightened beings eternally exist as individuals with self-awareness", states Harvey, and is accessible by arahants from within their own bodies.[86] In some Dhammakaya tradition lineages, practitioners ritually offer food to these enlightened beings in Nirvana.[86][105] Cholvijarn argues that Dhammakaya's teaching of Nirvana was influenced by two of Luang Pu Sodh's early meditation teachers, who taught a similar understanding of Nirvana.[106] Similar views were also taught by the 19th Supreme Patriarch of Thailand and are also common in the Thai Forest Tradition founded by Ajahn Mun, with several of Ajahn Mun's esteemed students giving similar descriptions of Nirvana, states Cholvijarn.[107] Such views can be found in borān kammaṭṭhana texts as well.[108]

Differences between temples

[edit]The various Dhammakaya temples have different expectations and emphasis, states Newell.[109] The meditation system at Wat Paknam is embedded within religious ceremonies; Wat Phra Dhammakaya and Wat Luang Phor Sodh Dhammakayaram use meditation retreats; Wat Luang Phor Sodh Dhammakayaram emphasizes higher stages of absorption to attain Dhammakaya in their publications, while Wat Phra Dhammakaya emphasizes developing calm and concentration.[110] Some Dhammakaya temples are more esoteric about the method than others. For instance, according to Mackenzie, Wat Paknam and Wat Phra Dhammakaya monks do not openly discuss their meditation practice related to defeating Māra.[34] Wat Luang Phor Sodh Dhammakayaram openly encourages meditation at higher levels, while Wat Phra Dhammakaya openly focuses on the basic level, as well as adapts simplified versions of the technique according to age and culture, teaching higher levels of meditation only to selected individuals.[63]

Scriptural validation

[edit]Temples of the tradition refer mostly to the Mahasatipaṭṭhāna Sutta, the Ānāpānasati Sutta and the Visuddhimagga for Dhammakaya meditation's theoretical foundations.[111] According to Cholvijarn, Luang Pu Sodh made the Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta and the four satipaṭṭhānas central to the Dhammakaya meditation system, being one of the first meditation masters of his time to do so.[112] According to Mackenzie, Luang Pu Sodh interpreted a phrase which is normally interpreted as 'contemplating the body as a body' as contemplating the body in the body.[18] The Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta contains a series of expressions for contemplating the body as body, feelings as feelings, etc. but is literally translated from Pali as "in" rather than "as". According to Cholvijarn, Luang Pu Sodh considered the phrase as having several meanings based on the individual person's level of understanding. Luang Pu Sodh did understand the phrase "body in body" as meaning being mindful of the body, but also understood it as extending the mindfulness to the inner bodies for practitioners who could see them with meditative attainments, a literal interpretation of "in".[113] Luang Pu Sodh's experience is also understood in the biographies as a deeper meaning to the Middle Way, a teaching described in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, an early Buddhist discourse.[114]

With regard to the Ānāpānasati Sutta, Cholvijarn points to a sermon of Luang Pu Sodh that described how the practice of mindfulness of the breath calms the body, speech and mind in regards to the four satipaṭṭhānas.[115] Jayamaṅggalo relates Dhammakaya meditation's focus on the center of the body to the practice of ānāpānasati in accordance with the Visuddhimagga. The Visuddhimagga instructs meditators to observe the passing of the breath at one fixed point, rather than to follow the breath in and out, which would agitate the mind. According to Jayamaṅggalo, Dhammakaya meditation follows these instructions by focusing at a point near the end of the breath, where the in and out breaths are separated in the abdomen.[116] Dhammakaya meditation's traditional use of a crystal ball to maintain focus at the center has also been compared to the use of a bright object as described in the Visuddhimagga.[117] The practice of visualizing an object at the end of the breath in the abdomen has been found in some ancient Thai meditation manuals as well, states Cholvijarn.[118]

Reception

[edit]The Dhammakaya tradition believes Dhammakaya meditation was the method through which the Buddha became enlightened, and that knowledge of the method was lost five hundred years after the Buddha's death, but was rediscovered by Luang Pu Sodh in the 1910s.[14][119] According to Suwanna Satha-Anand, the tradition believes that meditation and the attainment of the dhammakaya is the only way to Nirvana.[120]

Method

[edit]As with other meditation methods emphasizing samatha, opponents writing from a modernist standpoint have criticized the method. These critics point at the emphasis on pleasant feelings as opposed to insight. They argue against the mystical dimension of meditation practice, saying that bliss in meditation is a hindrance to insight.[121] According to Scott, in the time of Luang Pu Sodh the method was criticized by some for being extra-canonical,[122] although Asian studies scholar Edwin Zehner states there was no widespread criticism.[123] Meditation in large groups, as is common in the activities of Wat Phra Dhammakaya, contrasts with the emphasis of most Thai temples on meditation in solitude. The temple stresses the importance of meditating as a group to counterbalance the negativity in the world.[124]

Discussion within the Thai monastic community led to an inspection at Wat Paknam, but no fault could be found in Luang Pu Sodh's method.[22] Religion scholar Donald Swearer calls the meditation method "a unique method of meditation which involves a visualization technique not unlike that associated with certain yogic or tantric forms of meditation, and is easily taught to large groups of people".[125] Mackenzie concludes that the Dhammakaya meditation method is within the standards of Thai Buddhism, and that criticism of the method stems largely from people who disapprove of Wat Phra Dhammakaya's high-profile status and fundraising practices, rather than a genuine disagreement with the meditation method itself.[126]

Interpretation

[edit]The interpretations of the true self by the Dhammakaya tradition have been criticized by some Thai Buddhist scholars such as Phra Payutto, and have led to considerable debate in Thailand.[86] The bulk of Thai Theravada Buddhism rejects the true-self teaching of Dhammakaya, and insists upon absolute non-self as the Buddha's real teaching.[127] Proponents of the tradition cite several Pāli texts, such as one text stating that Nirvana is true happiness, and argue that the true self is a logical conclusion that follows from these texts. Other proponents feel that the problem is a matter of practice more than debate.[128][129] The late abbot of Wat Luang Por Sodh Dhammakayaram, Luang Por Sermchai, argues it tends to be scholars who hold the view of absolute non-self, whereas "several distinguished forest hermit monks" such as Luang Pu Sodh, Ajahn Mun and Ajahn Maha Bua hold Nirvana as true self, because they have "confirmed the existence of a Higher or Real Self (attā)" by their own realizations.[130][131]

The word dhammakāya in its orthodox sense is commonly understood as a figurative term, meaning the "body" or the sum of the Buddha's teachings.[132][133] The idea of a body of spiritual attainment can be found in the early Pali scriptures, though, but this is described as a "body accomplished by the mind" (Pali: manomayakāya) and not directly connected with the attainment of Nirvana. Buddhist studies scholar Chanida Jantrasrisalai, however, argues that the term was originally more connected with the process of enlightenment than the way it later came to be interpreted. Jantrasrisalai states that "in all references to dhammakāya in early Buddhist usage, it is apparent that dhammakāya is linked always with the process of enlightenment in one way or another. Its relation with the Buddhist noble ones of all types is evident in the early Buddhist texts. That is to say, dhammakāya is not exclusive to the Buddha. It appears also that the term's usage in the sense of teaching is a later schema rather than being the early Buddhist common notions as generally understood."[134]

The concept of the Dharmakāya has been much further developed in Mahāyāna Buddhism,[135] and the interpretations of the Dhammakaya tradition with regard to true self have been compared with Mahāyāna ideas like the Buddha Nature,[86] but such influence has been rejected by the tradition itself.[136]

Influence

[edit]Dhammakaya meditation has also influenced several meditation teachers outside of the Dhammakaya tradition. Cholvijarn points to Dhammakaya meditation as influencing several notable teachers in Thailand such as Luang Pho Ruesi Lingdam, bhikkhuni Voramai Kabilsingh, as well as possibly Phra Ariyakhunathan.[137]

Luang Pho Ruesi Lingdam, a highly respected figure in Thailand, studied meditation under Luang Pu Sodh and several well known meditation masters in the 1930s. After learning Dhammakaya meditation at Wat Paknam, he incorporated it into his practice and eventually became the abbot of Wat Tha Sung, which later became a major meditation temple for the region. Luang Pho Ruesi taught several meditation techniques, but his most popular was the Manomayiddhi method, which Cholvijarn notes has several similarities with Dhammakaya meditation.[138] Luang Pho Ruesi has also admitted that Luang Pu Sodh influenced his view of Nirvana, which he used to believe was void. However, after practicing Dhammakaya and other forms of meditation, he later changed his view to agree with Luang Pu Sodh's.[139]

Bhikkhuni Voramai Kabilsingh, the founder of the Songdhammakalyani Monastery and an early figure in the bhikkhuni ordination movement in Thailand, credits Dhammakaya meditation with sparking her interest in Buddhist practice and meditation.[140] According to her biography, Bhikkhuni Voramai was suffering from uterine fibroid as a layperson and prior to a surgery for their removal, was told by a student of Luang Pu Sodh that the fibroid had been removed via meditation. To her and the surgeon's surprise, the fibroid was found to be gone. The incident led her to the study of Dhammakaya meditation at Wat Paknam as well as several other meditation schools and her eventual ordination.[141] According to Cholvijarn, Bhikkhuni Voramai taught Dhammakaya meditation along with several other meditation methods until her death, as well as taught the concepts of dhammakaya and Nirvana similarly to Luang Pu Sodh.[142] As of 2008, Dhammakaya meditation is still taught as one of the meditation methods to the bhikkhuni at Songdhammakalyani Monastery.[143]

Phra Ariyakhunathan, a well known meditation master from the Thai Forest Tradition who was responsible for the first biography of lineage founder Ajahn Mun, also may have been influenced by Luang Pu Sodh.[137] Although Phra Ariyakhunathan does not acknowledge an influence, Cholvijarn notes that in 1950, Phra Ariyakhunathan, then a high ranking Dhammayuttika administrative monk, was sent to investigate the conduct of Luang Pu Sodh as his reputation in Thailand grew. After the meeting, Phra Ariyakhunathan returned with a positive report and then published a book describing the concept of dhammakaya in the same way as Luang Pu Sodh.[144] According to Cholvijarn, his understanding of dhammakaya likely came from discussions with meditation masters such as Luang Pu Sodh and Ajahn Mun, although Cholvijarn states that he also may have gotten these ideas from borān kammaṭṭhāna texts.[145]

Effects

[edit]

Practitioners of the method state the method is capable of changing people for the better, and has positive effects in their daily life.[121] Dhammakaya meditation has been promoted as a fast meditation method for professionals with little time, easy enough to be learned by children, one able to "effect radical changes in one's life if practised regularly".[146][147]

According to Mackenzie, Dhammakaya meditation is alleged to "increase the ability of the meditator to achieve goals, gain insight into the true nature of things", as well as develop "a variety of psychic and healing powers".[148] Such claims are found in other meditation traditions as well, states Mackenzie.[148]

Dhammakaya meditation is a form of spiritual practice that "fits well with a busy, consumer lifestyle". While the method is not simpler than other methods, states Mackenzie, its appeal is that its benefits seem to be more readily experienced by its adherents than more orthodox models.[147] According to Mackenzie, Dhammakaya meditation practice includes both the ordinary level and the high-level meditation. The claimed benefits of the low-level meditation include "spiritual purification, wisdom and success", while high-level meditation is alleged to bring forth various special knowledge and powers.[43]

Supranormal knowledge and powers

[edit]According to Newell, Dhammakaya meditation at the higher levels is believed by its adherents to bring forth abhiñña, or mental powers. Through such powers, states Newell, practitioners believe they can see different realms of the cosmos described in the Buddhist cosmology.[149] The Dhammakaya meditation technique is claimed in its advanced stages to allow the meditator to visit alternate planes of existence, wherein one can affect current circumstances.[150] According to Thai Studies scholar Jeffrey Bowers, high-level meditation is believed to yield various supernatural abilities such as enabling "one to visit one's own past lives, or the lives of others, discover where someone has been reborn and know the reasons why the person was reborn there, cure oneself or others of any disease, extrasensory perception, mind control and similar accomplishments".[151] Mackenzie describes these abilities as being in line with the psychic powers (Pali: iddhi) gained through meditation detailed in the Pali Canon.[43]

Examples include stories known in Thailand of Luang Pu Sodh performing "miraculous healings" and developing various supernatural powers "such as the ability to read minds and to levitate".[152][153][154][155] These alleged abilities of Luang Pu Sodh are believed even by Thais who are not his followers.[156] According to Mackenzie, Wat Paknam was a popular bomb shelter for people in the surrounding areas in World War II due to stories of Luang Pu Sodh's abilities, and Thai news reports include multiple sightings of mae chi (nuns) from the temple levitating and intercepting bombs during the Allied bombings of Bangkok.[155][157] According to Dhammakaya publications, Luang Pu Sodh realized that the Allies were planning to drop an atom bomb on Bangkok during World War II due to the Japanese occupation of Thailand. He and his advanced students are alleged to have used Dhammakaya meditation to change the mind of the Allies and prevent the strike.[154][158] According to Newell, many Thais try accessing the alleged powers of Dhammakaya meditation indirectly through amulets. Like many temples, Wat Paknam issued amulets to fund Buddhist projects when Luang Pu Sodh was abbot. These amulets eventually gained a reputation for being particularly powerful and are highly prized in Thailand for this reason.[159]

Practitioners also believe that Dhammakaya meditation can be used to extinguish the negative forces in the cosmos (Māra),[86] which has strongly affected the attitudes of practitioners at Dhammakaya tradition temples, who therefore hold that Dhammakaya meditation is not only important for the individual, but also for the cosmos at large.[67][160][161] Such powers are believed to be able to be used for the benefit of society at large.[155][149] Group meditation is believed by the Dhammakaya practitioners to be more powerful in defeating Māra.[162] The links to the supernatural world, and the tradition's leadership skills to navigate it, are also the basis for the ritual offering of food to the Buddha in nirvana, on the first Sunday of every month.[163]

Scientific study

[edit]Sudsuang, Chentanez and Veluvan (1990), studying 52 males practicing Dhammakaya meditation versus a control group of 30 males who did not practice meditation, concluded that Dhammakaya meditation reduced serum cortisol level, blood pressure, pulse rate, vital capacity, tidal volume, maximal voluntary ventilation and reaction time.[164] On a psychological level, people who regularly practiced Dhammakaya meditation were found to score high on the ISFJ personality type of the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator, which is defined within that scale as originality and a drive for implementing ideas and achieving goals.[165]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Some sources state 1884 as year of birth.[2][3]

- ^ There are differing timelines as to when this occurred. Some scholars indicate 1915,[13] others 1916[14] or 1917.[15]

- ^ According to Mackenzie, the mantra means "righteous Absolute of Attainment which a human being can achieve".[18] Scott states it refers to "a fully enlightened person", a phrase traditionally reserved for praising the Buddha. It is found in the common Theravada tradition chant such as, "Namo Tassa Bhagavato Arahato Samma Sambuddhassa".[19][20] The repetitive "samma araham" mantra chanting is also found in the meditation practice of North Thailand.[21]

- ^ In some respects its teachings resemble the Buddha-nature doctrines of Mahayana Buddhism. Paul Williams has commented that this view of Buddhism is similar to ideas found in the shentong teachings of the Jonang school of Tibet made famous by Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen.[24]

- ^ Named after Thai monks from the Ayutthaya Kingdom. Their influence stretched as far as Sri Lanka, where a revival of Buddhist meditation took place in the 1750s.[30]

- ^ Mackenzie compares this with Russian dolls nestled within each other.[77]

- ^ This is the intermediate state between not being enlightened yet and the four stages of enlightenment.[84]

- ^ Newell quotes Jayamaṅggalo, that these are "like diamond Buddha statues, crowned with a budding lotus".[80]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Newell 2008, pp. 238–9.

- ^ Fuengfusakul 1998, p. 23.

- ^ Scott 2009, p. 52.

- ^ Scott 2009, p. 66.

- ^ a b Mackenzie 2007, pp. 37, 216 with note 24.

- ^ a b Zehner 1990, p. 406 with footnotes.

- ^ Rhys Davids & Stede 1921, entries on Dhamma, Vijjā and Kāya.

- ^ Dhammachai International Research Institute of Australia and New Zealand. Tham-top kho songsai rueang Thammakai ถาม-ตอบ ขอสงสัยเรื่องธรรมกาย [Answering questions about Dhammakaya]. Vol. 1. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Newell 2008, pp. 177, 212.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 268.

- ^ Newell 2008, pp. 212, 227.

- ^ Newell 2008, pp. 178, 212, 219, 224–8.

- ^ a b Harvey 2013, p. 389.

- ^ a b c Newell 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Awirutthapanich, Pichit; Pantiya, Punchai (2017). หลักฐาน ธรรมกายในคัมภีร์พุทธโบราณ ฉบับวิชาการ 1 [Dhammakaya Evidence in Ancient Buddhist Books, Academic Version 1]. Songklanakarin Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 23 (2). Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Sirikanchana 2010, p. 885.

- ^ a b c d e Mackenzie 2007, pp. 112–113, 224n15.

- ^ a b c d Mackenzie 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Scott 2009, p. 210 with note 62.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 238 with footnote 10.

- ^ a b c d e Newell 2008, p. 238.

- ^ a b c Fuengfusakul 1998, p. 24.

- ^ a b Williams 2009, p. 126.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 237.

- ^ a b c d Newell 2008, pp. 256–7.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 327 n.73.

- ^ Crosby 2000, pp. 141–143, 149–153, 160.

- ^ Newell 2008, pp. 268–70.

- ^ Crosby 2012, p. 121.

- ^ Crosby, Skilton & Gunasena 2012.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 263.

- ^ Crosby, Skilton & Gunasena 2012, p. 178 n.1.

- ^ Skilton & Choompolpaisal 2017, p. 87 n.10.

- ^ a b Mackenzie 2007, p. 95.

- ^ Terwiel 2019, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Choompolpaisal 2019, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Newell 2008, p. 256.

- ^ a b Fuengfusakul 1998, pp. 90–1.

- ^ Bowers 1996.

- ^ Newell 2008, pp. 257 with footnote 62.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, pp. 113, 224n15.

- ^ Dhammakaya Foundation 1996, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d Mackenzie 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Dhammakaya Open University 2010, p. 139.

- ^ Dhammakaya Open University 2010, pp. 39, 97.

- ^ "Worldwide Coordination centers". Dhammakaya Foundation. 2016. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Newell 2008, pp. 117–9, 235.

- ^ a b Schedneck 2016, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Schedneck 2015.

- ^ McDaniel 2010, p. 661.

- ^ Bechert 1994, p. 259.

- ^ a b c Tanabe 2016, pp. 127–8.

- ^ a b c d Scott 2009, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e Fuengfusakul 1998, p. 84.

- ^ a b c Tanabe 2016, p. 127.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, p. 149, 268, 388.

- ^ Skilton & Choompolpaisal 2015, p. 222, n. 51.

- ^ a b Harvey 2013, pp. 389–390.

- ^ Fuengfusakul 1998, pp. 82–4.

- ^ a b c Zehner 2005, p. 2325.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, p. 14.

- ^ Chattinawat 2009, p. 57.

- ^ a b Cholvijarn 2019, p. 225-226.

- ^ a b c d e Scott 2009, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Harvey 2013, p. 3890.

- ^ a b c Newell 2008, pp. 238–239.

- ^ a b Hutter 2016.

- ^ Fuengfusakul 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Newell 2008, pp. 238–240.

- ^ a b c d Mackenzie 2007, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Mackenzie 2007, p. 108.

- ^ Tanabe 2016, p. 128.

- ^ Skilton & Choompolpaisal 2017, p. 94 n.21.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, p. 102-103.

- ^ a b c Mackenzie 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 83.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, pp. 103, 107, 113.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 239.

- ^ a b Fuengfusakul 1998, p. 87, Diagram 4.

- ^ a b c d e Newell 2008, pp. 240–1.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, p. 103, "... as with the previous bodies, these bodies have both a normal and refined form.".

- ^ a b c Mackenzie 2007, pp. 102–3.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 240.

- ^ Fuengfusakul 1998, pp. 85, 87, Diagram 4.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harvey 2013, p. 390.

- ^ a b Newell 2008, pp. 239–41.

- ^ Mongkhonthēpphamunī (Sodh) 2008, pp. 40–51.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, p. 111.

- ^ Fuengfusakul 1998, pp. 85, 88.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, p. 216 note 24.

- ^ a b Scott 2009, p. 81.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, p. 112, 225 note 32.

- ^ a b Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 201.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 202–203, 202 footnote 194.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 252.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 251–253.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 253–254.

- ^ a b Fuengfusakul 1998, pp. 85–8.

- ^ Fuengfusakul 1998, p. 85.

- ^ Scott 2009, p. 80b, "The full realization of this ultimate ontology is equated by many practitioners with the attainment of nirvāna, the cessation of greed, hatred, and delusion, and the attainment of ultimate and permanent happiness (nibbānaṃ paramaṃ sukhaṃ)." ... "One might argue that the description of nirvana in positive terms — nirvana as supreme happiness — rather than through a via negativa rendering of nirvana — nirvana is not samsara — may be one reason for the enormous success of the movement in drawing new members to its practice."

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 247.

- ^ Terwiel 2019, p. 14.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 313–316.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 65–81.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 85–86, 295–296.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 248.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 238, 246–8.

- ^ See Schedneck (2015),Hutter (2016), Newell (2008, pp. 249–50) and Cholvijarn (2019, pp. 13).

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 25.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 50–55.

- ^ Dhammakaya Foundation 1996, p. 46.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, pp. 268–269.

- ^ See Tanabe (2016, p. 127), Fuengfusakul (1998, p. 84), Newell (2008, p. 238) and Scott (2009, p. 80).

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, p. 135-136, 149.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, p. 76.

- ^ Satha-Anand, Suwanna (1 January 1990). "Religious Movements in Contemporary Thailand: Buddhist Struggles for Modern Relevance". Asian Survey. 30 (4): 395–408. doi:10.2307/2644715. JSTOR 2644715.

- ^ a b Scott 2009, p. 81–2.

- ^ Scott 2009, p. 82.

- ^ Zehner 2005, p. 2324.

- ^ Litalien 2010, p. 159.

- ^ Swearer 1991, p. 660.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, p. 112.

- ^ Seeger 2010, p. 71, n.39–40.

- ^ Fuengfusakul 1998, pp. 92–3.

- ^ Chalermsripinyorat, Rungrawee (2002). "Doing the Business of Faith: The Capitalistic Dhammakaya Movement and the Spiritually-thirsty Thai Middle Class" (PDF). Manusya: Journal of Humanities. 5 (1): 14–20. doi:10.1163/26659077-00501002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Williams 2009, pp. 127–8.

- ^ Seeger 2009, pp. 13 footnote 40.

- ^ Reynolds, Frank E. (1977). "The Several Bodies of Buddha: Reflections on a Neglected Aspect of Theravada Tradition". History of Religions. 16 (4): 374–389. doi:10.1086/462774. JSTOR 1062637. S2CID 161166753. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Fuengfusakul 1998, p. 89.

- ^ Jantrasrisalai, Chanida (2008). Early Buddhist Dhammakaya: Its Philosophical and Soteriological Significance (PDF) (PhD thesis). Sydney: Department of Studies in Religion, University of Sydney. p. 288. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

In all references to dhammakāya in early Buddhist usage, it is apparent that dhammakāya is linked always with the process of enlightenment in one way or another. Its relation with the Buddhist noble ones of all types is evident in the early Buddhist texts. That is to say, dhammakāya is not exclusive to the Buddha. It appears also that the term's usage in the sense of teaching is a later schema rather than being the early Buddhist common notions as generally understood.

- ^ Fuengfusakul 1998, p. 90.

- ^ Williams 2009, pp. 126–7.

- ^ a b Cholvijarn 2019, p. 229-230.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, p. 230-240.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, p. 239-240.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, p. 250.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, p. 250-251.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, p. 251-255.

- ^ Newell 2008, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, p. 242-243.

- ^ Cholvijarn 2019, p. 242-247.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 242.

- ^ a b Mackenzie 2007, p. 65.

- ^ a b Mackenzie 2007, p. 113.

- ^ a b Newell 2008, p. 241.

- ^ Zehner 1990, pp. 406–407.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, p. 32 quoting Bowers (1996).

- ^ Scott 2009, pp. 80–1.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 95.

- ^ a b Scott 2009, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b c Mackenzie 2007, pp. 34–5.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 94.

- ^ Scott, Rachelle M. (2016). "Contemporary Thai Buddhism". In Jerryson, Michael (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-19-936238-7.

- ^ Cheng & Brown 2015.

- ^ Newell 2008, p. 95-96.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, pp. 32–3.

- ^ Falk, Monica Lindberg (2007). Making fields of merit: Buddhist female ascetics and gendered orders in Thailand (1st ed.). Copenhagen: NIAS Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-87-7694-019-5.

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, pp. 33–4, Quote: "The greater the number of people who are meditating at the same time, the more powerful the resultant force. This is one reason why Dhammakaya meditation is normally conducted in a group rather than meditators practising by themselves.".

- ^ Mackenzie 2007, pp. 68–9.

- ^ Sudsuang, Chentanez & Veluvan 1990, p. 544.

- ^ Thanissaro 2021, p. 594.

References

[edit]- Bechert, H. (1994), "Buddhist Modernism: Present Situation and Current Trends", Buddhism Into the Year 2000, Khlong Luang, Patumthani: Dhammakaya Foundation, ISBN 978-9748920931, archived from the original on 26 May 2021, retrieved 26 May 2021

- Bowers, J. (1996), Dhammakaya Meditation in Thai Society, Thai Studies Section Faculty of Arts

- Chattinawat, Nathathai (2009), สถานภาพของแม่ชี: กรณีศึกษาแม่ชีวัดปากน้ําภาษีเจริญ กรุงเทพฯ [Nun's status: A Case Study of Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen] (M.A. thesis) (in Thai), College of Interdisciplinary Studies, Thammasat University, archived from the original on 23 March 2016

- Cheng, Tun-jen; Brown, Deborah A. (2015), Religious Organizations and Democratization: Case Studies from Contemporary Asia, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-46105-0, archived from the original on 26 May 2021, retrieved 26 May 2021

- Cholvijarn, P. (2019), The Origins and Development of Sammā Arahaṃ Meditation: From Phra Mongkhon Thepmuni (Sot Candasaro) to Phra Thep Yan Mongkhon (Sermchai Jayamaṅgalo) (PhD thesis), University of Bristol, archived from the original on 6 May 2022, retrieved 9 July 2020

- Choompolpaisal, P. (22 October 2019), "Nimitta and Visual Methods in Siamese and Lao Meditation Traditions from the 17th Century to the Present Day", Contemporary Buddhism, 20 (1–2): 152–183, doi:10.1080/14639947.2018.1530836, S2CID 210445830

- Crosby, Kate (2000), "Tantric Theravada: A Bibliographic Essay on the Writings of Francois Bizot and Others on the Yogavacara Tradition", Contemporary Buddhism, I (2)

- Crosby, Kate; Skilton, Andrew; Gunasena, Amal (12 February 2012), "The Sutta on Understanding Death in the Transmission of Borān Meditation From Siam to the Kandyan Court", Journal of Indian Philosophy, 40 (2): 177–198, doi:10.1007/s10781-011-9151-y, S2CID 170112821

- Crosby, Kate (2012), Sasson, Vanessa R. (ed.), Little Buddhas: Children and Childhoods in Buddhist Texts and Traditions, Oxford University Press

- Dhammakaya Foundation (1996), The Life & Times of Luang Phaw Wat Paknam, Bangkok: Dhammakaya Foundation, ISBN 978-974-89409-4-6

- Dhammakaya Open University (2010), Exemplary conduct of the principal teachers of Vijja Dhammakaya (PDF), California, USA: Dhammakaya Open University, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2016, retrieved 19 April 2016

- Fuengfusakul, Apinya (1998), ศาสนาทัศน์ของชุมชนเมืองสมัยใหม่: ศึกษากรณีวัดพระธรรมกาย [Religious Propensity of Urban Communities: A Case Study of Phra Dhammakaya Temple] (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in Thai), Buddhist Studies Center, Chulalongkorn University, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2017, retrieved 28 July 2017

- Harvey, Peter (2013), An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4

- Hutter, M. (2016), "Buddhismus in Thailand und Laos" [Buddhism in Thailand and Laos], in Hutter, M.; Loseries, A.; Linder, J. (eds.), Theravāda-Buddhismus und Tibetischer Buddhismus (in German), Kohlhammer, ISBN 978-3-17-028499-9, archived from the original on 29 May 2021, retrieved 26 May 2021

- Litalien, Manuel (January 2010), Développement social et régime providentiel en thaïlande: La philanthropie religieuse en tant que nouveau capital démocratique [Social development and a providential regime in Thailand: Religious philanthropy as a new form of democratic capital] (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in French), Université du Québec à Montréal, archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2018, retrieved 14 March 2017

- Mackenzie, Rory (2007), New Buddhist Movements in Thailand: Towards an Understanding of Wat Phra Dhammakaya and Santi Asoke, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-13262-1

- McDaniel, J.T. (2010), "Buddhists in Modern Southeast Asia", Religion Compass, 4 (11): 657–668, doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2010.00247.x

- Mongkhonthēpphamunī (Sodh), Phra (2008), Visuddhivācā, 60th Dhammachai Education Foundation, ISBN 9789743498152, OCLC 988643495

- Newell, C.S. (2008), Monks, meditation and missing links: continuity, "orthodoxy" and the vijjā dhammakāya in Thai Buddhism (PhD thesis), Department of the Study of Religions, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, doi:10.25501/SOAS.00007499, archived from the original on 18 March 2017, retrieved 18 February 2018

- Rhys Davids, Thomas W.; Stede, William (1921), The Pali-English Dictionary (1st ed.), Chipstead: Pali Text Society, ISBN 978-81-208-1144-7, archived from the original on 27 February 2021, retrieved 20 February 2021

- Schedneck, B. (15 May 2015), Thailand's International Meditation Centers: Tourism and the Global Commodification of Religious Practices, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-44938-6, archived from the original on 16 March 2017, retrieved 20 September 2016

- Schedneck, B. (11 July 2016), "Thai Meditation Lineages Abroad: Creating Networks of Exchange", Contemporary Buddhism, 17 (2): 427–438, doi:10.1080/14639947.2016.1205767, S2CID 148501731

- Scott, Rachelle M. (2009), Nirvana for Sale? Buddhism, Wealth, and the Dhammakāya Temple in Contemporary Thailand, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1-4416-2410-9

- Seeger, Martin (2009), "Phra Payutto and Debates 'On the Very Idea of the Pali Canon' in Thai Buddhism", Buddhist Studies Review, 26 (1): 1–31, doi:10.1558/bsrv.v26i1.1

- Seeger, M. (2010), "Theravāda Buddhism and Human Rights, Perspectives from Thai Buddhism" (PDF), Buddhist Approaches to Human Rights, pp. 63–92, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2018

- Sirikanchana, Pataraporn (2010), "Dhammakaya Foundation", in Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (eds.), Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices (2 ed.), ABC-CLIO

- Skilton, A.T.; Choompolpaisal, P. (2015), "The Ancient Meditation System, Boran Kammaṭṭhāna, of Theravāda: Ānāpānasati in Kammatthan Majjima Baeb Lamdub", Buddhist Studies Review, 32 (2): 207–229, doi:10.1558/bsrv.v32i2.28172

- Skilton, A.T.; Choompolpaisal, P. (2017), "The Old Meditation (boran kammatthan), a pre-reform Theravāda meditation system from Wat Ratchasittharam: The piti section of the kammatthan matchima baep lamdap", Aséanie, 33: 83–116

- Sudsuang, Ratree; Chentanez, Vilai; Veluvan, Kongdej (16 November 1990), "Effect of buddhist meditation on serum cortisol and total protein levels, blood pressure, pulse rate, lung volume and reaction time", Physiology & Behavior, 50 (3): 543–8, doi:10.1016/0031-9384(91)90543-W, PMID 1801007, S2CID 32580887

- Swearer, Donald K. (1991), "Fundamentalistic Movements in Theravada Buddhism", in Marty, M.E.; Appleby, R.S. (eds.), Fundamentalisms Observed, The Fundamentalism Project, vol. 1, Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-50878-8, archived from the original on 13 August 2021, retrieved 26 May 2021

- Tanabe, Shigeharu (2016), "Resistance through Meditation: Hermits of King's Mountain in Northern Thailand", in Oscar Salemink (ed.), Scholarship and Engagement in Mainland Southeast Asia: A festschrift in honor of Achan Chayan Vaddhanaphuti, Silkworm Books, ISBN 9786162151187, archived from the original on 26 May 2021, retrieved 26 May 2021

- Terwiel, Barend Jan (31 March 2019), "The City of Nibbāna in Thai Picture Books of the Three Worlds", Contemporary Buddhism, 20 (1–2): 184–199, doi:10.1080/14639947.2018.1524625, S2CID 151086161

- Thanissaro, P. N. (2021), "Psychological type among Dhammakāya meditators in the West", Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 24 (6): 594–611, doi:10.1080/13674676.2020.1758648

- Williams, Paul (2009), Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations (2nd ed.), Taylor & Francis e-Library, ISBN 978-0-203-42847-4

- Zehner, Edwin (1990), "Reform Symbolism of a Thai Middle–Class Sect: The Growth and Appeal of the Thammakai Movement", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 21 (2): 402–426, doi:10.1017/S0022463400003301, JSTOR 20071200

- Zehner, Edwin (2005), "Dhammakāya Movement", in Jones, Lindsay (ed.), Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 4 (2nd ed.), Farmington Hills: Thomson Gale