Traditional African religions

| Part of a series on |

| Traditional African religions |

|---|

|

The beliefs and practices of African people are highly diverse, including various ethnic religions.[1][2] Generally, these traditions are oral rather than scriptural and are passed down from one generation to another through folk tales, songs, and festivals,[3][4][5] and include beliefs in spirits and higher and lower gods, sometimes including a supreme being, as well as the veneration of the dead, and use of magic and traditional African medicine. Most religions can be described as animistic[6][7] with various polytheistic and pantheistic aspects.[1][8] The role of humanity is generally seen as one of harmonizing nature with the supernatural.[1][9]

Spread[edit]

Adherents of traditional religions in Africa are distributed among 43 countries and are estimated to number over 100 million.[10][11]

Although most Africans today are adherents of Christianity or Islam, African people often combine the practice of their traditional beliefs with the practice of Abrahamic religions.[12][13][14][15][16] These two Abrahamic religions are widespread across Africa, though mostly concentrated in different areas. They have replaced indigenous African religions but are often adapted to African cultural contexts and belief systems. Abrahamic religious beliefs, especially monotheistic elements, such as the belief in a single creator god, was introduced into traditionally polytheistic African religions rather early.[17]

Followers of traditional African religions are also found around the world. In recent times, religions, such as the Yoruba religion and the Odinala religion (A traditional Igbo religion), are on the rise. The religion of the Igbo and Yoruba is popular in the islands of the Caribbean and portions of Central and South America. In the United States, Voodoo is more predominant in the states along the Gulf of Mexico.[18]

Basics[edit]

Highly complex animistic beliefs builds the core concept of traditional African religions. This includes the worship of tutelary deities, nature worship, ancestor worship and the belief in an afterlife, comparable to other traditional/nature religions[clarify] around the world, such as Japanese Shinto or ancient Greek and Roman religions. While some religions have a pantheistic worldview with a supreme creator god next to other gods and spirits, others follow a purely polytheistic system with various gods, spirits and other supernatural beings.[6] Traditional African religions also have elements of totemism, shamanism and veneration of relics.[19]

Traditional African religion, like most other ancient traditions around the world, were based on oral traditions. These traditions are not religious principles, but a cultural identity that is passed on through stories, myths and tales, from one generation to the next.[clarification needed] The community and ones family, but also the environment, plays an important role in one's personal life. Followers believe in the guidance of their ancestors spirits. Among many traditional African religions, there are spiritual leaders and kinds of priests. These persons are essential in the spiritual and religious survival of the community. There are mystics that are responsible for healing and 'divining' - a kind of fortune telling and counseling, similar to shamans. These traditional healers have to be called by ancestors or gods. They undergo strict training and learn many necessary skills, including how to use natural herbs for healing and other, more mystical skills, like the finding of a hidden object without knowing where it is. Traditional African religion believe that ancestors maintain a spiritual connection with their living relatives. Most ancestral spirits are generally good and kind. Negative actions taken by ancestral spirits is to cause minor illnesses to warn people that they have gotten onto the wrong path.[20]

Native African religions are centered on ancestor worship, the belief in a spirit world, supernatural beings and free will (unlike the later developed concept of faith). Deceased humans (and animals or important objects) still exist in the spirit world and can influence or interact with the physical world. Forms of polytheism was widespread in most of ancient African and other regions of the world, before the introduction of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. An exception was the short-lived monotheistic religion created by Pharaoh Akhenaten, who made it mandatory to pray to his personal god Aten (see Atenism).[21] This remarkable change to traditional Egyptian religion was however reverted by his youngest son, Tutankhamun.[22][23][24][25] High gods, along with other more specialized deities, ancestor spirits, territorial spirits, and beings, are a common theme among traditional African religions, highlighting the complex and advanced culture of ancient Africa.[25][26][27] Some research suggests that certain monotheistic concepts, such as the belief in a high god or force (next to many other gods, deities and spirits, sometimes seen as intermediaries between humans and the creator) were present within Africa, before the introduction of Abrahamic religions. These indigenous concepts were different from the monotheism found in Abrahamic religions.[25][28][29][26]

Traditional African medicine is also directly linked to traditional African religions. According to Clemmont E. Vontress, the various religious traditions of Africa are united by a basic Animism. According to him, the belief in spirits and ancestors is the most important element of African religions. Gods were either self-created or evolved from spirits or ancestors which got worshiped by the people. He also notes that most modern African folk religions were strongly influenced by non-African religions, mostly Christianity and Islam and thus may differ from the ancient forms.[7]

Traditional African religions generally hold the beliefs of life after death (a spirit world or realms, in which spirits, but also gods reside), with some also having a concept of reincarnation, in which deceased humans may reincarnate into their family lineage (blood lineage), if they want to, or have something to do.[30]

There are often similarities between traditional African religions located in the same subregion. Central Africa, for instance, has similar religious traditions in countries of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, and Malawi.[31] The people in these countries who follow traditional religious practices often venerate ancestors through rituals and worship the land or a "divinity" through "regional cults" or "shrine cults", respectively.[31]

Jacob Olupona, Nigerian American professor of indigenous African religions at Harvard University, summarized the many traditional African religions as complex animistic religious traditions and beliefs of the African people before the Christian and Islamic "colonization" of Africa. Ancestor veneration has always played a "significant" part in the traditional African cultures and may be considered as central to the African worldview. Ancestors (ancestral ghosts/spirits) are an integral part of reality. The ancestors are generally believed to reside in an ancestral realm (spiritworld), while some believe that the ancestors became equal in power to deities.[32]

The defining line between deities and ancestors is often contested, but overall, ancestors are believed to occupy a higher level of existence than living human beings and are believed to be able to bestow either blessings or illness upon their living descendants. Ancestors can offer advice and bestow good fortune and honor to their living descendants, but they can also make demands, such as insisting that their shrines be properly maintained and propitiated. A belief in ancestors also testifies to the inclusive nature of traditional African spirituality by positing that deceased progenitors still play a role in the lives of their living descendants.

Olupona rejects the western/Islamic definition of monotheism and says that such concepts could not reflect the complex African traditions and are too simplistic. While some traditions have a supreme being (next to other deities), others have not. Monotheism does not reflect the multiplicity of ways that the traditional African spirituality has conceived of deities, gods, and spirit beings. He summarizes that traditional African religions are not only religions, but a worldview, a way of life.[32]

Ceremonies[edit]

West and Central African religious practices generally manifest themselves in communal ceremonies or divinatory rites in which members of the community, overcome by force (or ashe, nyama, etc.), are excited to the point of going into meditative trance in response to rhythmic or driving drumming or singing. One religious ceremony practiced in Gabon and Cameroon is the Okuyi, practiced by several Bantu ethnic groups. In this state, depending upon the region, drumming or instrumental rhythms played by respected musicians (each of which is unique to a given deity or ancestor), participants embody a deity or ancestor, energy or state of mind by performing distinct ritual movements or dances which further enhance their elevated consciousness.[33]

When this trance-like state is witnessed and understood, adherents are privy to a way of contemplating the pure or symbolic embodiment of a particular mindset or frame of reference. This builds skills at separating the feelings elicited by this mindset from their situational manifestations in daily life. Such separation and subsequent contemplation of the nature and sources of pure energy or feelings serves to help participants manage and accept them when they arise in mundane contexts. This facilitates better control and transformation of these energies into positive, culturally appropriate behavior, thought, and speech. Also, this practice can give rise to those in these trances uttering words which, when interpreted by a culturally educated initiate or diviner, can provide insight into appropriate directions which the community (or individual) might take in accomplishing its goal.[34]

Spirits[edit]

Followers of traditional African religions pray to various spirits as well as to their ancestors.[35] This includes also nature, elementary and animal spirits. The difference between powerful spirits and gods is often minimal. Most African societies believe in several “high gods” and a large amount of lower gods and spirits. There are also some religions with a single supreme being (Chukwu, Nyame, Olodumare, Ngai, Roog, etc.).[36] Some recognize a dual god and goddess such as Mawu-Lisa.[37]

Traditional African religions generally believe in an afterlife, one or more Spirit worlds, and Ancestor worship is an important basic concept in mostly all African religions. Some African religions adopted different views through the influence of Islam or even Hinduism.[38][39]

Practices and rituals[edit]

There are more similarities than differences in all traditional African religions,[40] although Jacob Olupona has written that it is difficult to truly generalize them because of the sheer amount of differences and variations between the traditions.[41] The deities and spirits are honored through libation or sacrifice (of animals, vegetables, cooked food, flowers, semi-precious stones and precious metals). The will of the gods or spirits is sought by the believer also through consultation of divinities or divination.[42] Traditional African religions embrace natural phenomena – ebb and tide, waxing and waning moon, rain and drought – and the rhythmic pattern of agriculture. According to Gottlieb and Mbiti:

The environment and nature are infused in every aspect of traditional African religions and culture. This is largely because cosmology and beliefs are intricately intertwined with the natural phenomena and environment. All aspects of weather, thunder, lightning, rain, day, moon, sun, stars, and so on may become amenable to control through the cosmology of African people. Natural phenomena are responsible for providing people with their daily needs.[43]

For example, in the Serer religion, one of the most sacred stars in the cosmos is called Yoonir (the Star of Sirius).[44] With a long farming tradition, the Serer high priests and priestesses (Saltigue) deliver yearly sermons at the Xooy Ceremony (divination ceremony) in Fatick before Yoonir's phase in order to predict winter months and enable farmers to start planting.[45]

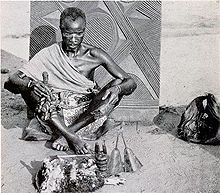

Traditional healers are common in most areas, and their practices include a religious element to varying degrees.

Divination[edit]

Since Africa is a large continent with many ethnic groups and cultures, there is not one single technique of casting divination. The practice of casting may be done with small objects, such as bones, cowrie shells, stones, strips of leather, or flat pieces of wood.

Some castings are done using sacred divination plates made of wood or performed on the ground (often within a circle).

In traditional African societies, many people seek out diviners on a regular basis. There are generally no prohibitions against the practice. Diviner (also known as priest) are also sought for their wisdom as counselors in life and for their knowledge of herbal medicine.

Ubuntu[edit]

Ubuntu is a Nguni Bantu term meaning "humanity". It is sometimes translated as "I am because we are" (also "I am because you are"), or "humanity towards others" (in Zulu, umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu). In Xhosa, the latter term is used, but is often meant in a more philosophical sense to mean "the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity". It is a collection of values and practices that people of Africa or of African origin view as making people authentic human beings. While the nuances of these values and practices vary across different ethnic groups, they all point to one thing – an authentic individual human being is part of a larger and more significant relational, communal, societal, environmental and spiritual world.[46]

Virtue and vice[edit]

Virtue in traditional African religion is often connected with carrying out obligations of the communal aspect of life. Examples include social behaviors such as the respect for parents and elders, raising children appropriately, providing hospitality, and being honest, trustworthy, and courageous.

In some traditional African religions, morality is associated with obedience or disobedience to God regarding the way a person or a community lives. For the Kikuyu, according to their primary supreme creator, Ngai, acting through the lesser deities, is believed to speak to and be capable of guiding the virtuous person as one's conscience.

In many cases, Africans who have converted to other religions have still kept up their traditional customs and practices, combining them in a syncretic way.[47]

Sacred places[edit]

Some sacred or holy locations for traditional religions include but not limited to Nri-Igbo, the Point of Sangomar, Yaboyabo, Fatick, Ife, Oyo, Dahomey, Benin City, Ouidah, Nsukka, Kanem-Bornu, Igbo-Ukwu, and Tulwap Kipsigis, among others.

Religious persecution[edit]

Traditional African religions have faced persecution from Christians and Muslims.[48][49] Adherents of these religions have been forcefully converted to Islam and Christianity, demonized and marginalized.[50] The atrocities include killings, waging war, destroying of sacred places, and other atrocities.[51][52]

Because of persecution and discrimination, as well as incompatibility with traditional society, culture and native beliefs, the Dinka people largely rejected or ignored Islamic and Christian teachings.[53]

Science and traditional worldviews[edit]

Bandama and Babalola (2023) states:[54]

The view of science as "embedded practice," intimately connected with ritual, for example, is considered "ascientific," "pseudo-science," or "magic" in Western perspective. In Africa, there is a strong connection between the physical and the terrestrial worlds. The deities and gods are the emissaries of the supreme God and the patrons in charge of the workability of the processes involved. In the Ile-Ife pantheon, for example, Olokun—the goddess of wealth—is considered the patron of the glass industry and is therefore consulted. Sacrifices are offered to appease her for a successful run. The same is true for ironworking. Current scholarship has reinforced the contributions of ancient Africa to the global history of science and technology.[54]

Traditions by region[edit]

This list is limited to a few well-known traditions.

Central Africa[edit]

- Bantu mythology (Central, Southeast, Southern Africa)

- Bushongo mythology (Congo)

- Kongo religion (Congo)

- Lugbara mythology (Congo)

- Baluba mythology (Congo)

- Mbuti mythology (Congo)

- Hausa animism (Chad, Gabon)

- Lotuko mythology (South Sudan)

Eastern Africa[edit]

- Kushite mythology (central parts of Sudan with origins in kerma culture)

- Bantu mythology (Central, Southeast, Southern Africa)

- Gikuyu mythology (Kenya)

- Akamba mythology

- Abaluhya mythology (Kenya)

- Dinka religion (South Sudan)

- Malagasy mythology (Madagascar)

- Maasai mythology (Kenya, Tanzania, Ouebian)

- Kalenjin mythology (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania)

- Dini Ya Msambwa (Bungoma, Trans Nzoia, Kenya)

- Waaqeffanna (Ethiopia and Kenya)

- Somali mythology (Somalia)

Northern Africa[edit]

- Ancient Egyptian religion (Egypt, Sudan)

- Kushite mythology (along the Nile valley in Sudan)

- Punic religion (Tunisia, Algeria, Libya)

- Traditional Berber religion (Morocco (including Western Sahara), Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso)

Southern Africa[edit]

- Bantu mythology (Central, Southeast, Southern Africa)

- Lozi mythology (Zambia)

- Tumbuka mythology (Malawi)

- Zulu traditional religion (South Africa)

- Badimo (South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho)

- San religion (Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa)

- Traditional healers of South Africa

- Indigenous religion in Zimbabwe

Western Africa[edit]

- Abwoi religion (Nigeria)

- Akan religion (Gana/Ghana, Ivory Coast)

- Dahomean religion (Benin, Togo)

- Efik religion (Nigeria, Cameroon)

- Edo religion (Benin kingdom, Nigeria)

- Hausa animism (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Gana/Ghana, Ivory Coast, Niger, Nigeria, Togo)

- Ijo religion (Ijo people, Nigeria)

- Godianism (a religion that is purported to encompass all traditional religions of Africa, primarily based on Odinala)

- Odinala (Igbo people, Nigeria)

- Asaase Yaa (Bono people (Gana/Ghana and Ivory Coast)

- Serer religion (A ƭat Roog) (Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania)

- Yoruba religion (Nigeria, Benin, Togo)

- Vodou (Gana/Ghana, Benin, Togo, Nigeria)

- Dogon religion (Mali)

- Ifa religion(Nigeria)

African diaspora[edit]

Afro-American religions involve ancestor worship and include a creator deity along with a pantheon of divine spirits such as the Orisha, Loa, Vodun, Nkisi and Alusi, among others. In addition to the religious syncretism of these various African traditions, many also incorporate elements of Folk Catholicism including folk saints and other forms of Folk religion, Native American religion, Spiritism, Spiritualism, Shamanism (sometimes including the use of Entheogens) and European folklore.

Various "doctoring" spiritual traditions also exist such as Obeah and Hoodoo which focus on spiritual health.[55] African religious traditions in the Americas can vary. They can have non-prominent African roots or can be almost wholly African in nature, such as religions like Trinidad Orisha.[56]

See also[edit]

- Folk religion – Expressions of religion distinct from the official doctrines of organized religion

- Witchcraft in Africa

Notes[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Encyclopedia of African Religion (Sage, 2009) Molefi Kete Asante

- ^ Ndlovu, Tommy Matshakayile (1995). Imikhuba lamasiko AmaNdebele. Doris Ndlovu, Bekithemba S. Ncube. Gweru,GasiyaZimbabwe: Mambo Press. ISBN 0-86922-624-X. OCLC 34114180.

- ^ Juergensmeyer, Mark (2006). The Oxford handbook of global religions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513798-1. OCLC 64084086.

- ^ Mbiti, John S. (1991). Introduction to African religion. Oxford [England]: Heinemann Educational Books. ISBN 0-435-94002-3. OCLC 24376978.

- ^ Nweke, Kizito Chinedu (2022-12-25). "Responding to new Imageries in African indigenous Spiritualties". Religious: Jurnal Studi Agama-Agama dan Lintas Budaya. 6 (3): 271–282. doi:10.15575/rjsalb.v6i3.20246. ISSN 2528-7249. S2CID 255213985.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kimmerle, Heinz (2006-04-11). "The world of spirits and the respect for nature: towards a new appreciation of animism". The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa. 2 (2): 15. doi:10.4102/td.v2i2.277. ISSN 2415-2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vontress, Clemmont E. (2005), "Animism: Foundation of Traditional Healing in Sub-Saharan Africa", Integrating Traditional Healing Practices into Counseling and Psychotherapy, SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 124–137, doi:10.4135/9781452231648, ISBN 9780761930471, retrieved 2019-10-31

- ^ An African Story BBC Archived November 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ What is religion? An African understanding Archived May 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Britannica Book of the Year (2003), Encyclopædia Britannica (2003) ISBN 978-0-85229-956-2 p.306

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, as of mid-2002, there were 480,453,000 Christians, 329,869,000 Muslims and 98,734,000 people who practiced traditional religions in Africa. Ian S. Markham, A World Religions Reader (1996) Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine is cited by Morehouse University as giving the mid-1990s figure of 278,250,800 Muslims in Africa, but still as 40.8% of the total. These numbers are estimates, and remain a matter of conjecture (see Amadu Jacky Kaba). The spread of Christianity and Islam in Africa: a survey and analysis of the numbers and percentages of Christians, Muslims and those who practice indigenous religions. The Western Journal of Black Studies, Vol 29, Number 2, (June 2005), discusses the estimations of various almanacs and encyclopedias, placing Britannica's estimate as the most agreed on figure. Notes the figure presented at the World Christian Encyclopedia, summarized here Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, as being an outlier. On rates of growth, Islam and Pentecostal Christianity are highest, see: The List: The World's Fastest-Growing Religions, Foreign Policy, May 2007. - ^ Lugira, Aloysius M., African Traditional Religions (New York: Chelsea House, 2009), p. 36 [in] Varghese, Roy Abraham, Christ Connection: How the World Religions Prepared the Way for the Phenomenon of Jesus, Paraclete Press (2011), p. 1935, ISBN 9781557258397 [1] (Retrieved 24 March 2019)

- ^ Mbiti, John S (1992). Introduction to African religion. East African Publishers. ISBN 9780435940027.When Africans are converted to other religions, they often mix their traditional religion with the one to which they are converted. In this way they are not losing something valuable, but are gaining something from both religious customs

- ^ Riggs, Thomas (2006). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Religions and denominations. Thomson Gale. p. 1. ISBN 9780787666125.Although a large proportion of Africans have converted to Islam an Christianity, these two world religions have been assimilated into African culture, and many African Christians and Muslims maintain traditional spiritual beliefs

- ^ Gottlieb, Roger S (2006-11-09). The Oxford handbook of religion and ecology. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780195178722.Even in the adopted religions of Islam and Christianity, which on the surface appear to have converted millions of Africans from their traditional religions, many aspect of traditional religions are still manifest

- ^ "US study sheds light on Africa's unique religious mix". AFP. Archived from the original on April 25, 2010.t doesn't seem to be an either-or for many people. They can describe themselves primarily as Muslim or Christian and continue to practice many of the traditions that are characteristic of African traditional religion," Luis Lugo, executive director of the Pew Forum, told AFP.

- ^ Quainoo, Samuel Ebow (2000-01-01). In Transitions and consolidation of democracy in Africa. Global Academic. ISBN 9781586840402.Even though the two religions are monotheistic, most African Christians and Muslims convert to them and still retain some aspects of their traditional religions

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica Book of the Year 2003. Encyclopædia Britannica, (2003) ISBN 9780852299562 p.306. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, as of mid-2002, there were 376,453,000 Christians, 329,869,000 Muslims and 98,734,000 people who practiced traditional religions in Africa. Ian S. Markham,(A World Religions Reader. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 1996.) is cited by Morehouse University as giving the mid-1990s figure of 278,250,800 Muslims in Africa, but still as 40.8% of the total. These numbers are estimates, and remain a matter of conjecture. See Amadu Jacky Kaba. The spread of Christianity and Islam in Africa: a survey and analysis of the numbers and percentages of Christians, Muslims and those who practice indigenous religions. The Western Journal of Black Studies, Vol 29, Number 2, June 2005. Discusses the estimations of various almanacs and encyclopedium, placing Britannica's estimate as the most agreed figure. Notes the figure presented at the World Christian Encyclopedia, summarized here, as being an outlier. The World Book Encyclopedia has estimated that in 2002 Christians formed 40% of the continent's population, with Muslims forming 45%. It was also estimated in 2002 that Christians form 45% of Africa's population, with Muslims forming 40.6%.

- ^ "Ancient African Religion Finds Roots In America". NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- ^ Asukwo (2013). "The Need to Re-Conceptualize African Traditional Religion".

- ^ "African Traditional Religion | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 2021-06-19.

- ^ Hornung, Erik (2001). Akhenaten and the religion of light. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8725-0. OCLC 48417401.

- ^ Hexham, Irvin ((1981), Lord of the Sky-King of the earth: Zulu Traditional Religion and Belief in the Skrelicsy God, Sciences Religieuses Studies in Religion, vol. 10: 273-78)

- ^ Busia, K. A. (1963). "Has the distinction between primitive and higher religions any sociological significance ?". Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions. 16 (1): 22–25. doi:10.3406/assr.1963.1996.

- ^ Peterson, Olof. "Foreigen influences on the idea of God in African religions".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Okwu AS (1979). "Life, Death, Reincarnation, and Traditional Healing in Africa". Issue: A Journal of Opinion. 9 (3): 19–24. doi:10.2307/1166258. JSTOR 1166258.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stanton, Andrea L. (2012). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE. ISBN 9781412981767.

- ^ Baldick, Julian (1997). Black God: the Afroasiatic roots of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim religions. Syracuse University Press:ISBN 0-8156-0522-6

- ^ The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800, by Christopher Ehret, James Currey, 2002

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (November 2004). "A Conversation with Christopher Ehret". World History Connected (Interview). Interviewed by Laichas, Tom. Retrieved 30 May 2020. (Citation with date provided here)

- ^ Ndemanu, Michael T. (January 2018). "Traditional African religions and their influences on the worldviews of Bangwa people of Cameroon". Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad. 30. Ball State University; Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad: 70–84. doi:10.36366/frontiers.v30i1.405.

There is an unwavering belief in life after death in traditional African religions with some even believing in reincarnation...

- ^ Jump up to: a b Salamone, Frank A. (2004). Levinson, David (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religious Rites, Rituals, and Festivals. New York: Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 0-415-94180-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chiorazzi, Anthony (2015-10-06). "The spirituality of Africa". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- ^ Karade, B. The Handbook of Yoruba Religious Concepts, pages 39–46. Samuel Weiser Inc, 1994

- ^ Annemarie De Waal Malefijt (1968) Religion and Culture: an Introduction to Anthropology of Religion, p. 220–249, Macmillan

- ^ "The spirituality of Africa". Harvard Gazette. 2015-10-06. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ Willie F. Page (2001) Encyclopedia of African History and Culture, Volume 1, p. 55. Published by Facts on File, ISBN 0-8160-4472-4

- ^ Peter C. Rogers (2009) Ultimate Truth, Book 1, p100. Published by AuthorHouse, ISBN 1-4389-7968-1

- ^ Parrinder, E. G. (1959). "Islam and West African Indigenous Religion". Numen. 6 (2): 130–141. doi:10.2307/3269310. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 3269310.

- ^ Ndemanu, Michael T. (January 2018). "Traditional African religions and their influences on the worldviews of Bangwa people of Cameroon". Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad. 30: 70–84. doi:10.36366/frontiers.v30i1.405.

- ^ John S. Mbiti (1990) African Religions & Philosophy 2nd Ed., p 100–101, Heinemann, ISBN 0-435-89591-5

- ^ Olupona, Jacob K. (2014). African Religions: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-979058-6. OCLC 839396781.

- ^ John S. Mbiti (1992) Introduction to African Religion 2nd Ed., p. 68, Published by East African Publishers ISBN 9966-46-928-1

- ^ Roger S. Gottlieb (2006) The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology, p. 261, Oxford Handbooks Online ISBN 0-19-517872-6

- ^ Henry Gravrand (1990) La Civilisation Sereer Pangool, PP 21, 152, Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Sénégal, ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

- ^ Simone Kalis (1997) Médecine Traditionnelle, Religion et Divination Chez les Seereer Siin du Sénégal: La Coonaissance de la Nuit, L'Harmattan, ISBN 2-7384-5196-9

- ^ Mugumbate, Jacob Rugare; Chereni, Admire (2020-04-23). "Editorial: Now, the theory of Ubuntu has its space in social work". African Journal of Social Work. 10 (1). ISSN 2409-5605.

- ^ Resolving the Prevailing Conflicts Between Christianity and African (Igbo) Traditional Religion Through Inculturation, by Edwin Anaegboka Udoye

- ^ Anne C. Bailey, African Voices of the Atlantic Slave Trade: Beyond the Silence and the Shame.

- ^ M. Darrol Bryant, Rita H. Mataragnon, The Many faces of religion and society (1985), Page 100, https://books.google.com/books?id=kv4nAAAAYAAJ:"African[permanent dead link] traditional religion went through and survived this type of persecution at the hands of Christianity and Islam..."

- ^ Garrick Bailey, Essentials of Cultural Anthropology, 3rd edn (2013), p. 268:"Later, during the nineteenth century, Christian missionaries became active in Africa and Oceania. Attempts by Christian missionaries to convert nonbelievers to Christianity took two main forms: forced conversions and proselytizing."

- ^ Festus Ugboaja Ohaegbulam, Towards and Understanding of the African Experience (1990), p. 161:"The role of Christian missionaries are a private interest group in European colonial occupation of Africa was a significant one...Collectively their activities promoted division within traditional African societies into rival factions...the picture denigrated African culture and religion..."

- ^ Toyin Falola et al., Hot Spot: Sub-Saharan Africa: Sub-Saharan Africa (2010), p. 7:"A religion of Middle Eastern origin, Islam reached Africa via the northern region of the continent by means of conquest. The Islamic wars of conquest that would lead to the Islamization of North Africa occurred first in Egypt, when in about 642 CE the country fell to the invading Muslim forces from Arabia. Over the next centuries, the rest of the Maghreb would succumb to Jihadist armies...The notion of religion conversion, whether by force or peaceful means, is foreign to indigenous African beliefs...Islam, however, did not become a religion of the masses by peaceful means. Forced conversion was an indispensable element of proselytization."

- ^ Beswick, S. F. (1994). "Non-Acceptance of Islam in the Southern Sudan: The Case of the Dinka from the Pre-Colonial Period to Independence (1956)". Northeast African Studies. 1 (2/3): 19–47. doi:10.1353/nas.1994.0018. ISSN 0740-9133. JSTOR 41931096. S2CID 143871492.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bandama, Foreman; Babalola, Abidemi Babatunde (13 September 2023). "Science, Not Black Magic: Metal and Glass Production in Africa". African Archaeological Review. 40 (3): 531–543. doi:10.1007/s10437-023-09545-6. ISSN 0263-0338. OCLC 10004759980. S2CID 261858183.

- ^ Eltis, David; Richardson, David (1997). Routes to slavery: direction, ethnicity, and mortality in the transatlantic slave trade. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 0-7146-4820-5.

- ^ Houk, James (1995). Spirits, Blood, and Drums: The Orisha Religion in Trinidad. Temple University Press. ISBN 1566393507.

References[edit]

- Information presented here was gleaned from World Eras Encyclopaedia, Volume 10, edited by Pierre-Damien Mvuyekure (New York: Thomson-Gale, 2003), in particular pp. 275–314.

- Baldick, J (1997) Black God: The Afroasiatic Roots of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Religions. New York: Syracuse University Press.

- Doumbia, A. & Doumbia, N (2004) The Way of the Elders: West African Spirituality & Tradition. Saint Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications.

- Ehret, Christopher, (2002) Civilizations of Africa: a History to 1800. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

- Ehret, Christopher, An African Classical Age: Eastern and Southern Africa in World History, 1000 B.C. to A.D. 400, page 159, University of Virginia Press, ISBN 0-8139-2057-4

- Karade, B (1994) The Handbook of Yoruba Religious Concepts. York Beach, MA: Samuel Weiser Inc.

- P'Bitek, Okot. African Religions and Western Scholarship. Kampala: East African Literature Bureau, 1970.

- Princeton Online, History of Africa

- Wiredu, Kwasi Toward Decolonizing African Philosophy And Religion in African Studies Quarterly, The Online Journal for African Studies, Volume 1, Issue 4, 1998

Further reading[edit]

- Encyclopedia of African Religion, - Molefi Asante, Sage Publications, 2009 ISBN 1412936365

- Abimbola, Wade (ed. and trans., 1977). Ifa Divination Poetry NOK, New York).

- Baldick, Julian (1997). Black God: the Afroasiatic roots of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim religions. Syracuse University Press:ISBN 0-8156-0522-6

- Barnes, Sandra. Africa's Ogun: Old World and New (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989).

- Beier, Ulli, ed. The Origins of Life and Death: African Creation Myths (London: Heinemann, 1966).

- Bowen, P.G. (1970). Sayings of the Ancient One - Wisdom from Ancient Africa. Theosophical Publishing House, U.S.

- Chidester, David. "Religions of South Africa" pp. 17–19

- Cole, Herbert Mbari. Art and Life among the Owerri Igbo (Bloomington: Indiana University press, 1982).

- Danquah, J. B., The Akan Doctrine of God: A Fragment of Gold Coast Ethics and Religion, second edition (London: Cass, 1968).

- Einstein, Carl. African Legends, First English Edition, Pandavia, Berlin 2021. ISBN 9783753155821

- Gbadagesin, Segun. African Philosophy: Traditional Yoruba Philosophy and Contemporary African Realities (New York: Peter Lang, 1999).

- Gleason, Judith. Oya, in Praise of an African Goddess (Harper Collins, 1992).

- Griaule, Marcel; Dietterlen, Germaine. Le Mythe Cosmogonique (Paris: Institut d'Ethnologie, 1965).

- Idowu, Bolaji, God in Yoruba Belief (Plainview: Original Publications, rev. and enlarged ed., 1995)

- LaGamma, Alisa (2000). Art and oracle: African art and rituals of divination. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-933-8. Archived from the original on 2013-05-10.

- Lugira, Aloysius Muzzanganda. African traditional religion. Infobase Publishing, 2009.

- Mbiti, John African Religions and Philosophy (1969) African Writers Series, Heinemann ISBN 0-435-89591-5

- Opoku, Kofi Asare (1978). West African Traditional Religion Kofi Asare Opoku | Publisher: FEP International Private Limited. ASIN: B0000EE0IT

- Parrinder, Geoffrey. African Traditional Religion, Third ed. (London: Sheldon Press, 1974). ISBN 0-85969-014-8 pbk.

- Parrinder, Geoffrey. "Traditional Religion", in his Africa's Three Religions, Second ed. (London: Sheldon Press, 1976, ISBN 0-85969-096-2), p. [15-96].

- Peavy, D., (2009)."Kings, Magic & Medicine". Raleigh, NC: SI.

- Peavy, D., (2016). The Benin Monarchy, Olokun & Iha Ominigbon. Umewaen: Journal of Benin & Edoid Studies: Osweego, NY.

- Popoola, S. Solagbade. Ikunle Abiyamo: It is on Bent Knees that I gave Birth (2007 Asefin Media Publication)

- Soyinka, Wole, Myth, Literature and the African World (Cambridge University Press, 1976).

- Alice Werner, Myths and Legends of the Bantu (1933). Available online at sacred-texts.com

- Umeasigbu, Rems Nna. The Way We Lived : Ibo Customs and Stories (London: Heinemann, 1969).

External links[edit]

Media related to Traditional African religions at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Traditional African religions at Wikimedia Commons- African Comparative Belief

- Afrika world.net A website with extensive links and information about traditional African religions Archived 2019-06-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Baba Alawoye.com Baba'Awo Awoyinfa Ifaloju, showcasing Ifa using web media 2.0 (blogs, podcasting, video & photocasting)[dead link]

- culture-exchange.blog/animism-modern-africa An article explaining the parallels between traditional and modern religious practices in Africa