Spanish Army

| Spanish Army | |

|---|---|

| Ejército de Tierra | |

Seal of the Spanish Army | |

| Founded | 15th century |

| Country | |

| Type | Army |

| Role | Land force |

| Size | 75,822 personnel (2018)[1] |

| Part of | |

| Garrison/HQ | Buenavista Palace, Madrid |

| Mascot(s) | Crowned rampant eagle with Saint James cross |

| Commanders | |

| Commander in Chief | |

| Chief of Staff of the Army | |

| Insignia | |

| Flag patch |  |

| Aircraft flown | |

| Attack helicopter | Tiger |

| Reconnaissance | Airbus EC-665 Tiger |

| Trainer | Colibrí EC135 |

| Transport | Chinook Cougar NH90 |

The Spanish Army (Spanish: Ejército de Tierra, lit. 'Army of Land') is the terrestrial army of the Spanish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is one of the oldest active armies – dating back to the late 15th century.

The Spanish Army has existed continuously since the reign of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella (late 15th century). The oldest and largest of the three services, its mission was the defence of Peninsular Spain, the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands, Melilla, Ceuta and the Spanish islands and rocks off the northern coast of Africa.

History

[edit]

During the 16th century, Habsburg Spain saw steady growth in its military power. The Italian Wars (1494–1559) resulted in an ultimate Spanish victory and hegemony in northern Italy by expelling the French. During the war, the Spanish Army transformed its organization and tactics, evolving from a primarily pike and halberd wielding force into the first pike and shot formation of arquebusiers and pikemen. During the 16th century, this formation evolved into the tercio infantry formation.

Backed by the financial resources drawn from the Americas,[3] Spain fought wars against its enemies, such as the long-running Dutch Revolt (1568–1609), defending Christian Europe from Ottoman raids and invasions, supporting the Catholic cause in the French civil wars and fighting England during the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604). The Spanish Army grew in size from around 20,000 troops in the 1470s to around 300,000 troops by the 1630s during the Thirty Years' War that tore Europe apart, requiring the recruitment of soldiers from across Europe.[4] With such numbers involved, Spain had trouble funding the war effort on so many fronts. The non-payment of troops led to many mutinies and events such as the Sack of Antwerp (1576), in which 17,000 people died.[5]

The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) drew in Spain alongside most other European states. Spain entered the conflict with a strong position, but the ongoing fighting gradually eroded her advantages; first Dutch, then Swedish innovations had made the tercio more vulnerable, having less flexibility and firepower than its more modern equivalents.[6] Nevertheless, Spanish armies continued to win major battles and sieges throughout this period across large swathes of Europe. French entry into the war in 1635 put additional pressure on Spain, with the French victory at the Battle of Rocroi in 1643 being a major boost for the French. By the signing of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Spain was forced to accept the independence of the Dutch Republic.

18th century

[edit]Spain remained an important naval and military power, depending on critical sea lanes stretching from Spain through the Caribbean and South America, and westwards towards Manila and the Far East.

The Army was reorganized on the French model and in 1704 the old Tercios were transformed into Regiments. The first modern military school (the Artillery School) was created in Segovia in 1764. Finally, in 1768 King Charles III sanctioned the "Royal Ordinances for the Regime, Discipline, Subordination, and Service in His Armies", which were in force until 1978.[7]

Napoleonic era and Restoration

[edit]In the late 18th century, Bourbon-ruled Spain had an alliance with Bourbon-ruled France and therefore did not have to fear a land war. Its only serious enemy was Britain, which had a powerful Royal Navy; Spain, therefore, concentrated its resources on its Navy. When the French Revolution overthrew the Bourbons, a land war with France became a danger which the king tried to avoid.

In Spanish Army the officer corps was selected primarily on the basis of royal patronage, rather than merit. About a third of the junior officers had been promoted from the ranks, and they did have talent, but they had few opportunities for promotion or leadership. The rank-and-file were poorly trained peasants. Elite units included foreign regiments of Irishmen, Italians, Swiss, and Walloons, in addition to elite artillery and engineering units. In combat, small units fought well, but their old-fashioned tactics were hard to use against the French Grande Armée, despite repeated desperate efforts at last-minute reform.[8]

In 1808, Napoleon tried to depose Carlos IV of Spain and install his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne, sparking the Peninsular War. Initially, there was little resistance and Spain was occupied. Soon, however, Spanish units began to reorganize and set up guerrilla warfare, culminating in a Spanish victory at the Battle of Bailén within the first two months of the war. The defeated French evacuated the peninsula all the way to the Ebro valley near the Pyrenees, suffering many humiliating defeats against the regular Spanish Army. They were among the first sound defeats of the hitherto seemingly unbeatable Imperial French Army, forcing Napoleon to intervene personally with massive forces, but also sparked the War of the Fifth Coalition, as other European powers, led by Austria, were encouraged to declare war on France. The situation steadily worsened for the French although Napoleon brought more effective troops into the peninsula, as the guerrilla insurgents increasingly took control of Spain's battle against Napoleon and created a more or less unified underground national resistance, for which traditional armies of the time were not organized or prepared for yet.[9] By 1812, however, the army controlled only scattered enclaves, and could only harass the French with occasional raids.[10] Fortunately for the Spanish, the disastrous French invasion of Russia severely weakened the French Army and forced Napoleon to cut troop concentrations in Spain, ultimately allowing the Army, militia and their British allies to drive the French out of Spain by 1814.

During the 19th century

[edit]

The Spanish Army emerged from the Napoleonic Wars devastated as a result of years of destructive conflict during the Peninsular War.[11] A series of conflicts in Spain's American colonies with the aim of political independence from the Spanish Empire, which had broken out in 1808, led to the loss of a majority of these colonial possessions by 1833.[12] During these conflicts, numerous armies from Spain were dispatched to Spanish America in order to defeat the Latin American revolutionaries; these efforts proved mostly unsuccessful. Combined with disturbances in Spain against the Spanish government, Spain's military strength suffered further during the post-Napoleonic era of the early 19th century. Recognizing the need to reform the Spanish Army, reforms were passed by the government of Spain during this period to reform and modernize the armed forces into a professional standing army; as part of these reforms, conscription was adopted by the Spanish Army. This grew the size of the Army to 250,000 in 1828, and it increased in 1830 to 300,000 soldiers. This therefore made the Spanish Army a relatively strong Army in Europe, though internal conflicts did affect the Army, forcing them to chose sides.[citation needed]

Spain faced a series of internal dynastic conflicts, collectively known as the Carlist Wars (1833–1876), during the 19th century; these conflicts led the Spanish state to undergo a series of reforms directed at its military, administrative, and social structures.[13] As consequence of the Carlist Wars, and the weakness of the central structures of government under the Spanish monarchy, many generals with political ambitions staged coup d'états, known as pronunciamientos, which continued to occur until Bourbon Restoration in Spain under King Alfonso XII. These military interventions against the civil government eventually shaped a permissive cultural and political mentality, with a tacit expectation in Spain of "special emergency interventions" from the military that would pervade well into the first third of the 20th century.[14] In 1920, the Spanish Army was composed of roughly 500,000 men, many of whom would participate in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939).[citation needed]

First World War

[edit]Second Republic (1931–36)

[edit]During the Second Spanish Republic, the Spanish government enlisted over ten million men to the army.

Civil War (1936–39)

[edit]Some US citizens came to Spain to fight in their civil war for two main reasons. The first being to promote their ideals and the other being to escape the trials of living in North America during the great depression.

The Americans totaled 2,800 and suffered heavy casualties: 900 killed and 1,500 wounded.

The Spanish Army under the Francoist Regime (1939–1975)

[edit]This period can be divided in four phases:[15]

- 1939–1945: Second World War

- 1945–1954: International Isolation (lack of means)

- 1954–1961: Agreement with the United States (a certain improvement in means and capabilities)

- 1961–1975: Development plans (economic basis for the modernisations that follows in the 1970s and 1980s).

Second World War

[edit]

At the end of the Civil War, the Spanish (Francoist) Army counted with 1,020,500 men, in 60 Divisions.[16] During the first year of peace, Franco dramatically reduced the size of the Spanish Army to 250,000 in early 1940, with most soldiers two-year conscripts.[17] A few weeks after the end of the war, the eight traditional Military Regions (Madrid, Sevilla, Valencia, Barcelona, Zaragoza, Burgos, Valladolid, and the VIII Military Region at La Coruña) were reestablished. In 1944 the IX Military Region, with its headquarters in Granada, was created.[16] The Air Force became an independent service, under its own Ministry of the Air Force.

Concerns about the international situation, Spain's possible entry into the Second World War, and threats of invasion led Franco to undo some of these reductions. In November 1942, with the Allied landings in North Africa and the German occupation of Vichy France bringing hostilities closer than ever to Spain's border, Franco ordered a partial mobilization, bringing the army to over 750,000 men.[17] The Air Force and Navy also grew in numbers and in budgets, to 35,000 airmen and 25,000 sailors by 1945, although for fiscal reasons Franco had to restrain attempts by both services to undertake dramatic expansions.[17]

During the Second World War, the Army in metropolitan Spain had eight Army Corps, with two or three Infantry Divisions each.[18] Additionally, the Army of Africa had two Army Corps in Northern Africa, and there were the Canary Islands General Command and the Balearic Islands General Command, one Cavalry Division, plus the Artillery's General Reserve. In 1940 a Reserve Group, with three Divisions, was created.[16]

Although Spanish caudillo Francisco Franco was neutral and did not bring Spain into World War II on the side of Nazi Germany, he permitted volunteers to join the German Army (Wehrmacht) on the condition they would only fight against the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front, and not against the Western Allies or any Western European occupied populations. In this manner, he could keep Spain at peace with the Western Allies, while repaying German support during the Spanish Civil War and providing an outlet for the strong anti-Communist sentiments of many Spanish nationalists. Officially designated as División Española de Voluntarios by the Spanish Army and as 250 Infanterie-Division in the German Army, the Blue Division was the only component of the German Army to be awarded a medal of their own, commissioned by Hitler in January 1944 after the Division had demonstrated its effectiveness in impeding the advance of the Red Army, on the Volkhov front (October 1941 – August 1942) and in the siege of Leningrad (August 1942 – October 1943), mainly at the battle of Krasny Bor.[19]

International isolation

[edit]At the end of the Second World War, the Spanish Army counted 22,000 officers, 3,000 NCO and almost 300,000 soldiers. The equipment dated from the Civil War, with some systems produced in Germany during the World War. Their doctrines and training were obsolete, as they had not incorporated the teachings of the Second World War; Scianna elaborates on the weaknesses of equipment, political role, and worldview.[20] This situation lasted until the agreements with the United States in September 1953.[15]

Agreement with the United States (Barroso Reform, 1957)

[edit]After the signing of the military agreement with the United States in 1953, the assistance received from Washington allowed Spain to procure more modern equipment and to improve the country's defence capabilities. More than 200 Spanish officers and NCOs received specialised training in the United States each year. With the Barroso Reform (1957), the Spanish Army abandoned the organisation inherited from the Civil War to adopt the United States' pentomic structure. General Instruction 158/107 of 1958 led to the raising of three experimental infantry divisions (DIE 11, 21, 31 at Madrid, Algeciras, and Valencia respectively).[21] Instruction 160/115 of January 15, 1960 extended these changes to another five transformation divisions (DIT, at Gerona, Málaga, Oviedo, Vigo, Vitoria, respectively) and the four mountain divisions (divisións de infantería de montaña, DIM).[22] Most of the heavy divisions had five manoeuvre agrupaciones based on two to three regiments and support formations, while the Mountain Divisions "Urgel" 42, 51, 52, and "Navarra" 62 had six batallón de cazadores de montaña anchored on two to three regiments, an independent company, and what appears to be a battalion of motorised infantry.[23]

All in all, after the Barroso Reform, the Spanish Army had eight Pentomic infantry divisions, four mountain divisions, the 'Brunete' Armoured Division, the "Jarama" Cavalry Division, organized into a division HQ and four armoured groups ("agrupaciones blindadas"), three independent Armoured Brigades at rather a reduced strength and three Field Artillery Brigades ("Brigada de artillería de campaña") with assigned artillery groups.[15]

Years of economic development (1965)

[edit]The 1965 Reforms were inspired by then-contemporary French organisation and doctrine. The Menéndez Tolosa reforms from 1965 divided the Army into two categories: the Immediate Intervention Forces (FII, Field Army) and the Defensa Operativa del Territorio (DOT, Operational Territorial Defence (Territorial Army)) territorial forces.

The FII had the mission of defending the Pyrenean and the Gibraltar frontiers and of fulfilling Spain's security commitments abroad. It was to be "an army corps equipped and trained for conventional and limited nuclear warfare, ready to be deployed within or outside national borders."[24] It was made up of:

- Armoured Division No. 1 "Brunete", with two armoured Brigades;

- Mechanised Infantry Division "Guzmán el Bueno" No. 2, with Mechanised Infantry Brigade XXI (BRIMZ XXI) at Cordoba,[25] and Motorised Infantry Brigade XXII (BRIMT XXII) at Jerez;[26]

- Motorised Division "Maestrazgo" No. 3 with its headquarters in Valencia and two brigades;

- Parachute Brigade (raised 1973)

- Air-Transportable Brigade

- Armoured Cavalry Brigade

- Army Corps support units

The DOT was to maintain security in the regional commands and of reinforce the Civil Guard and the police against subversion and terrorism. It comprised nine independent Infantry Brigades (one in every one of the Military Regions of Spain), organized with a brigade HQ and two infantry battalions each; the Mountain Infantry Division No. 4 "Urgell"[27] and Mountain Infantry Division No. 6 "Navarra";[26] the Mountain Reserve of the Army High Command; the Canary Islands, Balearic Islands, Ceuta and Melilla commands, with their respective DOT units including the Regulares (six groups later reduced to four) and the Spanish Legion (4 Tercios); and the Army General Reserve Command, composed of DOT units working as the reserve force of the Army, the equivalent to the United States Army Reserve.[15]

During the last years of the Francoist regime, contemporary weapons and vehicles were ordered for the Army. In 1973, the military education system was reformed in depth, in order to make its structure and objectives similar to those existing in the civilian universities. It was during this time that the Spanish Army fought in the campaigns in what is now Western Sahara against Arab forces in the area who agitated for the end of Spanish colonial rule.

The Spanish Army under King Juan Carlos I and beyond

[edit]Initial years (1975–1989)

[edit]

Three main events characterise this period: creation of a single Ministry of Defence (1977) to replace the three existing military ministries (Army, Navy and Air Ministries), the failed coup d'état in February 1981 and the accession to NATO in 1982.

The Modernización del Ejército de Tierra (META) plan was carried out from 1982 to 1988 so that Spain could achieve full compliance with NATO standards.[28] Military regions in mainland Spain were reduced from nine to six; the Intervention Force (FII) and the Territorial Defence (DOT) were merged; the number of brigades was reduced from 24 to 15; and personnel numbers cut from 279,000 to 230,000.

After the end of the Cold War (1989–present)

[edit]

The end of the Cold War came with the reduction of the term of military service for conscripts until its complete abolition in 2001[29] and the increasing participation of Spanish forces in multinational peacekeeping operations abroad[30] are the main drivers for changes in the Spanish Army after 1989.

Three reorganisation plans have been implemented since. First the RETO plan (1990), then the Norte plan (1994),[31] under which the now "Manoeuvre Force," located in the old Captaincy of Valencia, was reduced to an army corps equivalent of a complete heavy division and the equivalent of a light division with reduced support; and the Instruction for Organisation and Operation of the Army (IOFET) 2005.

Equipment and Personnel

[edit]Personnel

[edit]

In 2001, when compulsory military service was still in effect, the army was about 135,000 troops (50,000 officers and 86,000 soldiers). Following the suspension of conscription the Spanish Army became a fully professionalised volunteer force and by 2008 had a personnel strength of 75,000.[32] In case of a war or national emergency, an additional force of 80,000 Civil Guards comes under the Ministry of Defence command

Infantry Equipments

- Navaja-combat knife and utility knife

- Heckler & Koch USP – 9 mm semi-automatic pistol. Standard issue pistol

- Heckler & Koch MP5 – 9 mm submachine gun.

- Heckler & Koch UMP – Submachine gun in both 9 mm and .45 ACP

- Heckler & Koch G36E – 5.56 mm assault rifle. Standard Issue Rifle. Without integral red dot sight, Spanish variants use a Picatinny Rail to mount an EoTech holographic sight

- Heckler & Koch G36KE and G36CE – 5.56 mm Short barrel and carbine.

- CETME rifle – 5.56 mm NATO and 7.62 NATO rifle. Largely phased out and replaced by HK G36

- Rheinmetall MG3 – 7.62 mm NATO Standard issue medium machine gun

- Heckler & Koch MG4 – 5.56 mm Standard issue light machine gun

- Browning M2 HB QCB – 12.7mm heavy machine gun

- SB LAG 40 automatic grenade launcher

- Instalaza C-100 Alcotán – 100 mm anti-tank rocket launcher

- Instalaza C-90 CR (M3) – 90 mm disposable anti-tank rocket launcher

- Spike LR & ER – anti-tank missile launcher

- Milan 2T – anti-tank missile launcher

- TOW 2A – anti-tank missile launcher

- Barrett M95 – 12.7 mm heavy sniper rifle

- Accuracy International Arctic Warfare – 7.62 mm sniper rifle

- AXMC in .338LM

- ECIA L65/60 60 mm light mortar

- ECIA L65/81 mortar – 81 mm medium mortar

- ECIA L65/105 mortar – 105 mm medium mortar

- ECIA L65/120 mortar – 120 mm heavy mortar

Tanks

- 219 Leopardo 2E (A6) Main Battle Tank

- 108 Leopard 2 A4 Main Battle Tank ( with another 54 in reserve )

- Armoured Vehicles

- 261 Pizarro infantry fighting vehicles in two versions

- 500+ M113 armored personnel carriers in seven versions

- 90 TOM Bv206S tracked articulated vehicle

- 84 VRC-105B1 Centauro wheeled tank destroyer

- 4 VCREC Centauro

- 648 BMR-M1 medium six-wheeled APC

- 135 VEC-M1 cavalry scout vehicle

- 185 IVECO LMV Lince 4WD tactical infantry mobility vehicle (575 total order)

- 100 RG-31 Mk5E Nyala (MRAP) 4WD tactical vehicle (MRAP)

- 10 Cardom recoil mortar system (RMS)

- 6 Husky 2G (mine detection system)

- URO VAMTAC, all terrain 4x4 tactical vehicle (more than 1,500)

- Santana Anibal, an all terrain 4x4 utility vehicle (more than 1,500)

- Iveco Euro Cargo all terrain utility vehicle

- Volvo FH

- Iveco M250W.37

- VEMPAR tactical heavy lorry 450HP, 20-ton cargo lorry

- 41 Hidromek HMK102S backhoe loader[33]

- 5 Hidromek HMK 210W wheeled excavator[34]

Artillery

[edit]- M109A5 – 155/39 mm self-propelled howitzer, as the M109A5(+96)

- Santa Bárbara Sistemas 155/52 (84) -Howitzer

- L-118A1 – 105/37 mm light field howitzer (56) with Base Bleed (range 21 km) by Expal

Air defence

[edit]- Oerlikon-Contraves GDF-005 35/90 35 mm Anti-aircraft artillery piece (92)

- Raytheon MIM-104 Patriot – Surface-to-Air missile system (3 batteries)

- Skyguard-Aspide – Surface-to-Air missile system (13)

- NASAMS – Surface-to-Air missile system (8)

- MBDA SATCP Mistral missile – Anti-aircraft infrared homing missile system (168)

Aircraft

[edit]

| Type | Origin | Class | Role | Introduced | In service | Total | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agusta-Bell 212 | Rotorcraft | Utility | 6 | ||||

| Eurocopter AS332B1 Super Puma | Rotorcraft | Transport | 1982 | 16 | |||

| Eurocopter AS532UL Cougar | Rotorcraft | Transport | 1998 | 17 | |||

| Eurocopter EC-135 | Rotorcraft | Trainer/utility | 2008 | 16 | |||

| Eurocopter Tiger | Rotorcraft | Attack | 2007 | 20 | 4 on order | ||

| NHI NH90 | Rotorcraft | Transport | 2016 | 8 | 37 on order | ||

| Boeing CH-47D Chinook | Rotorcraft | Transport | 17 | To be upgraded to CH-47F by Boeing in 2019.[35] |

- 4 x INTA SIVA

- 4 x IAI Searcher MK II J –

Israel

Israel - 47 x RQ-11 Raven (mini UAV) –

United States

United States - 6 x 2 Atlantic and 4 Tucan

Formation and structure

[edit]Uniforms

[edit]

|

|

Digital woodland

|

Digital desert

|

Ranks and insignia

[edit]Commissioned officer ranks

[edit]The rank insignia of commissioned officers.

| NATO code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) | Student officer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capitán general | General de ejército | Teniente general | General de división | General de brigada | Coronel | Teniente coronel | Comandante | Capitán | Teniente | Alférez | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

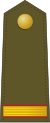

Other ranks

[edit]The rank insignia of non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel.

| NATO code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Suboficial mayor | Subteniente | Brigada | Sargento primero | Sargento | Cabo mayor | Cabo primero | Cabo | Soldado de primera | Soldado | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]- Army of Spain (Peninsular War)

- FAMET

- Spanish Legion

- Spanish Republican Army

- Coats of Arms, Badges and Emblems of the Spanish Army

- List of military weapons of Spain

References

[edit]- ^ "España Hoy 2016–2016". lamoncloa.gob.es (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "Real Decreto 866/2021, de 5 de octubre, por el que se nombra Jefe de Estado Mayor del Ejército de Tierra al Teniente General del Cuerpo General del Ejército de Tierra don Amador Fernando Enseñat y Berea". boe.es. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Elton, p. 181.

- ^ Anderson, p. 17.

- ^ Carlton, 2011: p. 42.

- ^ Meade, p. 180.

- ^ "Comparative Atlas of Defence in Latin America / 2008 Edition, p. 42 (PDF)" (PDF). resdal.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Charles J. Esdaile, The Spanish Army in the Peninsular War (1988)

- ^ Russell Crandall (2014). America's Dirty Wars: Irregular Warfare from 1776 to the War on Terror. Cambridge UP. p. 21. ISBN 978-1107003132. Archived from the original on 30 November 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Otto Pivka, Spanish Armies of the Napoleonic Wars (Osprey Men-at-Arms, 1975)

- ^ Palmer, A. W. A Dictionary of Modern History 1789–1945. Penguin Reference Books: London. (1962)

- ^ Adelman, Jeremy. Sovereignty and Revolution in the Iberian Atlantic. Princeton University Press 2006. ISBN 978-0691142777

- ^ Holt, Edgar. The Carlist Wars in Spain (1967)

- ^ Carr, Raymond. Spain, 1808–1975 (1982), pp. 184–195

- ^ a b c d Puell de la Villa, Fernando (2010). "El devenir del Ejército de Tierra (1945–1975)". In Fernando Puell de la Vega y Sonia Alda Mejías (ed.). Los Ejércitos del franquismo. Madrid: IUGM-UNED. 2010. pp. 63–96.

- ^ a b c Muñoz Bolaños, Roberto (2010). "La institución militar en la posguerra (1939–1945)". In Fernando Puell de la Vega y Sonia Alda Mejías (ed.). Los Ejércitos del franquismo. Madrid: IUGM-UNED. 2010. pp. 15–55.

- ^ a b c Bowen, Wayne H.; José E. Álvarez (2007). A Military History of Modern Spain. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 114. ISBN 978-0275993573. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ López 2017.

- ^ Luca de Tena, Torcuato (1976). Embajador en el infierno (Ambassador to Hell). Barcelona: Editorial Planeta. pp. 15–22. ISBN 8432021520.

- ^ Scianna 2019.

- ^ Lopéz 2017, pp. 63, 64.

- ^ Lopéz 2017, pp. 63, 64, 102.

- ^ Lopéz 2017, p. 65.

- ^ López 2017, p. 68.

- ^ Note another source says the brigade was created at Badajoz on 10 de julio de 1965, https://ejercito.defensa.gob.es/unidades/Cordoba/brimzx_guzmanelbueno/Historial/index.html

- ^ a b López 2017, p. 69.

- ^ "Franquicias de Correos". sanfilatelio.afinet.org.

- ^ Yárnoz, Carlos (10 February 1983). "El plan de modernización del Ejército de Tierra renovará completamente la estructura actual". El País. elpais.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ See an announcement by the Minister of Defence Archived 6 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ministerio de Defensa – Misiones internacionales". Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Cervera Arteaga, Eva. "Retrospectiva de tres décadas en el Ejército de Tierra español". Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Estadística de Personal Militar de Complemento, Militar Profesional de Tropa y Marinería y Reservista Voluntario (PDF)" (PDF). mde.es. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Ayyıldız, Akif (5 January 2024). "Türkiye'den İspanya'ya zırhlı iş makinası ihracatı". DefenceTurk (in Turkish). Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Ayyıldız, Akif (5 January 2024). "Türkiye'den İspanya'ya zırhlı iş makinası ihracatı". DefenceTurk (in Turkish). Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Waldron, Greg (4 January 2019). "Boeing to upgrade Spain CH-47D fleet to -F standard". Flight Global. Singapore. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Army Ranks & Insignia". Ejército de Tierra. Ministry of Defence (Spain). Retrieved 30 May 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Instruction no. 59/2005, of 4 April 2005, from the chief of the army staff on army organisation and function regulations, published in B.O.D. NO. 80 of 26 April 2005

- Lehardy, Diego, Spanish Army in a difficult phase of its transformation, RID magazine, July 1991.

- Mogaburo López, Fernando (2017). Historia Orgánica De Las Grandes Unidades (1475–2018) (PDF). Madrid: Ministerio de Defensa – Mando de Adiestramiento y Doctrina. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- Scianna, Bastian Matteo (2019). "Stuck in the past? British views on the Spanish army's effectiveness and military culture, 1946–1983". War and Society. 38 (1): 41–56. doi:10.1080/07292473.2019.1524347. S2CID 159007579. Antiquated material and limited budgets were not the only reasons for the army's low potential wartime capability after World War II. "..Spain continued to field around twenty divisions, whereas the defence industry and available national resources could only sustain six operational divisions. A regular Spanish infantry division could muster full strength with modern infantry weapons, while other ‘teeth’ units – like the artillery and engineers – were reduced to one-third of their ideal levels. The supporting ‘tail’ was so underdeveloped that divisions were statically bound to their home depot and could only defend their military district after six months mobilisation.." [The paper] draws on British and German sources to demonstrate how Spanish military culture prevented an augmented effectiveness and organisational change.

External links and further reading

[edit]- Home page of the Spanish Land Army (in English)

- Recruitment page (in Spanish)

- The Spanish Military Forum