Émile Roux

Émile Roux | |

|---|---|

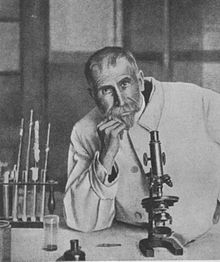

Roux (c. 1900) | |

| Born | 17 December 1853 |

| Died | 3 November 1933 (aged 79) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Pasteur Institute anti-diphtheria serum |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1917) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physiology, bacteriology, immunology |

Pierre Paul Émile Roux FRS[1] (17 December 1853 – 3 November 1933)[2] was a French physician, bacteriologist and immunologist. Roux was one of the closest collaborators of Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), a co-founder of the Pasteur Institute, and responsible for the institute's production of the anti-diphtheria serum, the first effective therapy for this disease. Additionally, he investigated cholera, chicken-cholera, rabies, and tuberculosis. Roux is regarded as a founder of the field of immunology.[3]

Early years

[edit]Roux was born in Confolens, Charente. It is believed that Roux had a fatherless childhood.[4] He received his baccalaureate in sciences in 1871 and started his studies in 1872 at the Medical School of Clermont-Ferrand. He worked initially as a student assistant in chemistry at the Faculty of Sciences, under Émile Duclaux. From 1874 to 1878, he continued his studies in Paris and was admitted as clinical assistant at Hôtel-Dieu. Between 1874 and 1877, Roux received a fellowship for the Military School at Val-de-Grâce, but quit it after failing to present his dissertation in due time. It is also believed that Roux may have been dismissed from the military for some form of insubordination.[4] In 1878, he started to work as an assistant to the course on fermentation given by his patron Duclaux at the Sorbonne University.[1]

In 1878, Pierre Paul Emile Roux married Rose Anna Shedlock, but it was kept a secret. Shedlock met Roux at the Paris medical school. Shedlock then died in 1879 of tuberculosis. In an inaccurate biography, Roux's niece stated that Shedlock contracted tuberculosis from Roux. However, this is unlikely, given that Shedlock had symptoms before marrying Roux.[5] According to his niece, Roux allegedly believed that marriage was an opportunity for women to satisfy their "deepest aspirations," while for men it was "mutilation".[4]

Work with Pasteur

[edit]Duclaux recommended Roux to Louis Pasteur, who was looking for assistants, and Roux joined Pasteur's laboratory as a research assistant from 1878 to 1883 at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. When Roux first began his career with Pasteur, he started as an animal inoculator. He performed well in the technical tasks, and became more involved with research.[4] Roux began his research on the microbiological causation of diseases, and in this capacity worked with Pasteur on avian cholera (1879–1880) and anthrax (1879–1890), and was involved in the famous experiment on anthrax vaccination of animals at Pouilly-le-Fort.[1] In this vaccination experiment, Pasteur and Roux injected 25 sheep with their anthrax vaccine, and the other 25 were unvaccinated. All 50 sheep were injected with the anthrax bacillus. All 25 vaccinated sheep survived, and all 25 unvaccinated sheep died, just as Pasteur and Roux predicted.[4]

Louis Pasteur and Émile Roux were sometimes in disagreement in their approach to disease. Pasteur was an experimental scientist, whereas Roux was more focused on clinical medicine. They also held different religious and political beliefs, with Pasteur being a right- leaning Catholic, and Roux being a left-leaning atheist. Given their many differences, they clashed often as they worked towards vaccines against anthrax and rabies. The main issues between Roux and Pasteur regarded the ethics of human experimentation, specifically, the amount of evidence from animal experimentation needed in order to justify giving the rabies vaccine to humans. Roux was more reluctant to give the vaccine to humans without further evidence that it was safe in animals.[4]

In 1883, he presented a doctoral dissertation in medicine titled Des Nouvelles Acquisitions sur la Rage, in which he described his research on rabies with Pasteur since 1881, which led to the development of the first vaccination against this fearsome disease. Roux discovered the idea of intracranial transmission of rabies, which paved the road for many more Pastorian milestones in research.[4] Roux was now recognized as an expert in the nascent sciences of medical microbiology and immunology. With Pasteur's other assistants (Edmond Nocard, Louis Thuillier, who died while in Alexandria after contracting the disease, and Straus), Roux traveled in 1883 to Egypt to study a human cholera outbreak there, but they were unable to find the pathogen for the disease, which was later discovered in Alexandria by the German physician Robert Koch (1843–1910).[1]

In 1883 and for the following 40 years, Émile Roux became closely involved with the creation of what was to become the Pasteur Institute. Roux is known for developing the concept of combining development, research, and application in a specialized hospital. The most distinctive feature of the Pasteur Hospital was free access to medical care. The hospital was also known for being very hygienic for the time period.[6] He divided his time between biomedical research and administrative duties. In 1888, an important year in his career, he accepted the position of Director of Services, joined the editorial board of the Annales de l’Institut Pasteur, and established the first regular course on microbiological technique, which would become extremely influential in the training of many important French and foreign researchers and physicians in infectious diseases.[7][1]

Diphtheria research

[edit]The development of a diphtheria anti-toxin serum was a race between researchers Emil Behring in Berlin, and Émile Roux in Paris. They both developed it nearly simultaneously. However, the serum was marketed differently in each country. In Germany, the serum was marketed in a private business setting, whereas in France, the serum was distributed through a communal health care system.[8] The race to develop the diphtheria anti-toxin serum was considered a national rivalry, although each team of researchers adopted each other's experimental practices and built off of each other.[9] In a controversy, the first Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine was given to Emil Von Behring for his work on the serum therapy for diphtheria. Roux had been nominated in 1888 for the isolation of the diphtheria toxin, but didn't win the prize in 1901 because his discovery was deemed to be too "old." Over the years, Roux came close to the Nobel Prize but never won.[10]

Also in 1883, Roux published, with Alexandre Yersin, the first of his classical works on the causation of diphtheria by the Klebs-Loeffler bacillus, then an extremely prevalent and lethal disease, particularly among children. Diphtheria is contagious microbial disease marked by throat lesions, polyneuritis, myocarditis, low blood pressure, and collapse. He studied its toxin and its properties, and began in 1891 to develop an effective serum to treat the disease, following the demonstration, by Emil Adolf von Behring (1854–1917) and Kitasato Shibasaburō (1852–1931) that antibodies against the diphtheric toxin could be produced in animals. He successfully demonstrated the use of this antitoxin with Auguste Chaillou in a study with 300 diseased children in the Hôpital des Enfants-Malades and was henceforth hailed as a scientific hero in medical congresses throughout Europe.[1]

Other research and later years

[edit]In the following years, Roux dedicated himself indefatigably to many investigations on the microbiology and practical immunology of tetanus, tuberculosis, syphilis, and pneumonia. He was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1900. In 1904, he was nominated to Pasteur's former position as General Director of the Pasteur Institute.[1]

In 1916, he moved to a small apartment in the Pasteur Hospital, where he died on 3 November 1933.

Awards and honors

[edit]- In 1917, he received the Copley Medal for his outstanding achievements in research.[11]

- Asteroid 293366 Roux, discovered by French amateur astronomer Bernard Christophe in 2007, was named in his memory.[12] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 12 March 2017 (M.P.C. 103971).[13]

- The Roux culture bottle, a flask for culturing cells, is named after him.[14]

Gallery

[edit]-

An injection against croup at the Hôpital Trousseau in Paris, with Roux observing, by P.A.A. Brouillet in 1893

-

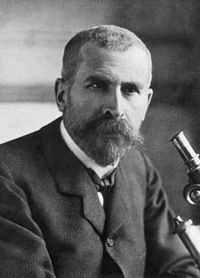

Dr. Emile Roux, Albert Edelfelt, 1896

-

Office in 1906

-

18th and 19th Century Medicine by Veloso Salgado in 1906, Pasteur at the center and Roux kneeling in front with the rabbit

-

Friendly caricature of members of the Academy of Medicine designed by Hector Moloch and published in the journal Chanteclair in 1910

-

Roux, unknown date

-

25th anniversary of the Pasteur Institute on 15 November 1913

-

Roux in 1927

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Pierre Paul Emile Roux. 1853-1933". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 1 (3): 197–204. 1934. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1934.0005.

- ^ Pierre Paul Émile Roux. Biographie. Institut Pasteur, Paris.

- ^ a g, N. (1934). "Pierre Paul Emile Roux". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 30 (1): 70–71. PMC 403187. PMID 20319369.

- ^ a b c d e f g GEISON, GERALD L. (1990). "Pasteur, Roux, and Rabies: Scientific versus Clinical Mentalities". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 45 (3): 341–365. doi:10.1093/jhmas/45.3.341. ISSN 0022-5045. PMID 2212608.

- ^ McIntyre, Neil (21 March 2014). "The fate of Rose Anna Shedlock (c1850–1878) and the early career of Émile Roux (1853–1933)". Journal of Medical Biography. 24 (1): 60–67. doi:10.1177/0967772013513992. ISSN 0967-7720. PMID 24658208. S2CID 43576406.

- ^ Opinel, Annick (May 2008). "The Emergence of French Medical Entomology: The Influence of Universities, the Institut Pasteur and Military Physicians (1890–c.1938)". Medical History. 52 (3): 387–405. doi:10.1017/s0025727300002696. ISSN 0025-7273. PMC 2449474. PMID 18641790.

- ^ "Emile Roux, pilies de l'aventure Pasteur". Pasteur. 9 November 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Hess, Volker (June 2008). "The Administrative Stabilization of Vaccines: Regulating the Diphtheria Antitoxin in France and Germany, 1894–1900". Science in Context. 21 (2): 201–227. doi:10.1017/s0269889708001695. ISSN 0269-8897. PMID 18831137. S2CID 423178.

- ^ Klöppel, Ulrike (June 2008). "Enacting Cultural Boundaries in French and German Diphtheria Serum Research". Science in Context. 21 (2): 161–180. doi:10.1017/s0269889708001671. ISSN 0269-8897. PMID 18831135. S2CID 23575164.

- ^ Franz., Luttenberger. Excellence and chance : the Nobel Prize case of E. von Behring and E. Roux. OCLC 1147879148.

- ^ "Notes and Records of the Royal Society". Royal Society Publishing. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ^ "293366 Roux (2007 EQ9)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Erhard F. Kaleta (2006): "A Brief History, Modes of Spread and Impact of Fowl Plague Viruses". Asia-Pacific Biotech News, volume 10, issue 14, pages 717-725. doi:10.1142/S0219030306001236

External links

[edit]- English biography of Pierre Paul Émile Roux. Pasteur Brewing

- Bibliography of P.P.E. Roux. Pasteur Institute.

- Paul de Kruif Microbe Hunters (Blue Ribbon Books) Harcourt Brace & Company Inc., New York 1926: ch. VI Roux and Behring: Massacre the Guinea Pigs (pp. 184–206)

- 1853 births

- 1933 deaths

- People from Charente

- French immunologists

- French microbiologists

- Academic staff of the University of Paris

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Foreign Members of the Royal Society

- Members of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala

![An injection against croup at the Hôpital Trousseau [fr] in Paris, with Roux observing, by P.A.A. Brouillet in 1893](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/An_injection_against_croup_at_the_H%C3%B4pital_Trousseau%2C_Paris._Wellcome_V0006764.jpg/339px-An_injection_against_croup_at_the_H%C3%B4pital_Trousseau%2C_Paris._Wellcome_V0006764.jpg)

![Friendly caricature of members of the Academy of Medicine designed by Hector Moloch [fr] and published in the journal Chanteclair in 1910](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/Dr._Emile_Roux.jpg/180px-Dr._Emile_Roux.jpg)