Standard Chinese

| Standard Chinese | |

|---|---|

| Standard Mandarin | |

| Native to | Mainland China, Taiwan, Singapore |

Native speakers | Began acquiring native speakers in 1988[1][2] L1 and L2 speakers: 80% of China[3] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

Early forms | |

| Signed Chinese[4] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | |

| Glottolog | None |

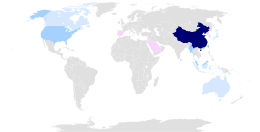

Countries where Standard Chinese is spoken

Majority native language

Statutory or de facto national working language

More than 1,000,000 L1 and L2 speakers

More than 500,000 speakers

More than 100,000 speakers | |

| Putonghua | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 普通話 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 普通话 | ||

| Literal meaning | Common speech | ||

| |||

| Guoyu | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 國語 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 国语 | ||

| Literal meaning | National language | ||

| |||

| Huayu | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 華語 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 华语 | ||

| Literal meaning | Chinese language | ||

| |||

Standard Chinese (simplified Chinese: 现代标准汉语; traditional Chinese: 現代標準漢語; pinyin: Xiàndài biāozhǔn hànyǔ; lit. 'modern standard Han speech') is a modern standard form of Mandarin Chinese that was first codified during the republican era (1912‒1949). It is designated as the official language of mainland China and a major language in the United Nations, Singapore, and Taiwan. It is largely based on the Beijing dialect. Standard Chinese is a pluricentric language with local standards in mainland China, Taiwan and Singapore that mainly differ in their lexicon.[7] Hong Kong written Chinese, used for formal written communication in Hong Kong and Macau, is a form of Standard Chinese that is read aloud with the Cantonese reading of characters.

Like other Sinitic languages, Standard Chinese is a tonal language with topic-prominent organization and subject–verb–object (SVO) word order. Compared with southern varieties, the language has fewer vowels, final consonants and tones, but more initial consonants. It is an analytic language, albeit with many compound words.

In the context of linguistics, the dialect has been labeled Standard Northern Mandarin[8][9][10] or Standard Beijing Mandarin,[11][12] and in common speech simply Mandarin,[13] better qualified as Standard Mandarin, Modern Standard Mandarin, or Standard Mandarin Chinese.

Naming

In English

Among linguists, Standard Chinese has been referred to as Standard Northern Mandarin[8][9][10] or Standard Beijing Mandarin.[11][12] It is colloquially referred to as simply Mandarin,[13] though this term may also refer to the Mandarin dialect group as a whole, or the late imperial form used as a lingua franca.[14][15][16][13] "Mandarin" is a translation of Guanhua (官話; 官话; 'bureaucrat speech'),[17] which referred to the late imperial lingua franca.[18] The term Modern Standard Mandarin is used to distinguish it from older forms.[17][19]

In Chinese

Guoyu and Putonghua

The word Guoyu (国语; 國語; 'national language')[17] was initially used during the late Qing dynasty to refer to the Manchu language. The 1655 Memoir of Qing Dynasty, Volume: Emperor Nurhaci (清太祖實錄) says: "(In 1631) as Manchu ministers do not comprehend the Han language, each ministry shall create a new position to be filled up by Han official who can comprehend the national language."[20] However, the sense of Guoyu as a specific language variety promoted for general use by the citizenry was originally borrowed from Japan in the early 20th century. In 1902, the Japanese Diet had formed the National Language Research Council to standardize a form of the Japanese language dubbed kokugo (国語).[21] Reformers in the Qing bureaucracy took inspiration and borrowed the term into Chinese, and in 1909 the Qing education ministry officially proclaimed imperial Mandarin to be the new national language.[22]

The term Putonghua (普通话; 普通話; 'common tongue')[17] dates back to 1906 in writings by Zhu Wenxiong to differentiate the standard vernacular Mandarin from Literary Chinese and other varieties of Chinese.

Usage concerns

The term "Countrywide common spoken and written language" (国家通用语言文字) has been used by the Chinese government since the 2010s, mostly targeting ethnic minority students.[citation needed] The term has strong legal connotations, as it is derived from the title of a 2000 law which defines Putonghua as the one and only "Countrywide Common Spoken and Written Language".

Use of the term Putonghua ('common tongue') deliberately avoids calling the dialect a 'national language', in order to mitigate the impression of coercing minority groups to adopt the language of the majority. Such concerns were first raised by the early Communist leader Qu Qiubai in 1931. His concern echoed within the Communist Party, which adopted the term Putonghua in 1955.[23][24] Since 1949, usage of the word Guoyu was phased out in the PRC, only surviving in established compound nouns, e.g. 'Mandopop' (国语流行音乐; Guóyǔ liúxíng yīnyuè), or 'Chinese cinema' (国语电影; Guóyǔ diànyǐng).

In Taiwan, Guoyu is the colloquial term for Standard Chinese. In 2017 and 2018, the Taiwanese government introduced two laws explicitly recognizing the indigenous Formosan languages[25][26] and Hakka[27][26] as "Languages of the nation" (國家語言) alongside Standard Chinese. Since then, there have been efforts to redefine Guoyu as encompassing all "languages of the nation", rather than exclusively referring to Standard Chinese.

Hanyu and Zhongwen

Among Chinese people, Hanyu (汉语; 漢語; 'Han language') refers to spoken varieties of Chinese. Zhongwen (中文; 'written Chinese')[28] refers to written Chinese. On the other hand, Among foreigners, the term Hanyu is most commonly used in textbooks and Standard Chinese education, such as in the Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi (HSK) test.

Huayu

Until the mid-1960s, Huayu (华语; 華語) referred to all the language varieties used among the Chinese nation.[29] For example, Cantonese, Mandarin, and Hokkien films produced in Hong Kong were imported into Malaysia and collectively known as "Huayu cinema" until the mid-1960s.[29] Gradually, the term has been re-appropriated to refer specifically to Standard Chinese. The term is mostly used in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines.[30]

History

The Chinese language has had considerable dialectal variation throughout its history, including prestige dialects and linguae francae used throughout the territory controlled by the dynastic states of China. For example, Confucius is thought to have used a dialect known as yayan rather than regional dialects; during the Han dynasty, texts also referred to tōngyǔ (通語; 'common language'). The rime books that were written starting in the Northern and Southern period may have reflected standard systems of pronunciation. However, these standard dialects were mostly used by the educated elite, whose pronunciation may still have possessed great variation. For these elites, the Chinese language was unified in Literary Chinese, a form that was primarily written, as opposed to spoken.

Late empire

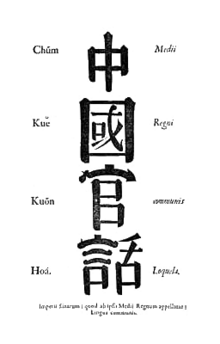

The term Guanhua (官話; 官话; 'official speech') was used during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties to refer to the lingua franca spoken within the imperial courts. The term "Mandarin" is borrowed directly from the Portuguese word mandarim, in turn derived from the Sanskrit word mantrin ('minister')—and was initially used to refer to Chinese scholar-officials. The Portuguese then began referring to Guanhua as "the language of the mandarins".[19]

The Chinese have different languages in different provinces, to such an extent that they cannot understand each other.... [They] also have another language which is like a universal and common language; this is the official language of the mandarins and of the court; it is among them like Latin among ourselves.... Two of our fathers [Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci] have been learning this mandarin language...

— Alessandro Valignano, Historia del Principio y Progresso de la Compañia de Jesus en las Indias Orientales (1542–1564)[32]

During the 17th century, the state had set up orthoepy academies (正音書院; zhèngyīn shūyuàn) in an attempt to conform the speech of bureaucrats to the standard. These attempts had little success: as late as the 19th century, the emperor had difficulty understanding some of his ministers in court, who did not always follow a standard pronunciation.

Before the 19th century, the lingua franca was based on the Nanjing dialect, but later the Beijing dialect became increasingly influential, despite the mix of officials and commoners speaking various dialects in the capital, Beijing.[33] By some accounts, as late as 1900 the position of the Nanjing dialect was considered by some to be above that of Beijing; the postal romanization standards established in 1906 included spellings that reflected elements of Nanjing pronunciation.[34] The sense of Guoyu as a specific language variety promoted for general use by the citizenry was originally borrowed from Japan; in 1902 the Japanese Diet had formed the National Language Research Council to standardize a form of the Japanese language dubbed kokugo (国語).[21] Reformers in the Qing bureaucracy took inspiration and borrowed the term into Chinese, and in 1909 the Qing education ministry officially proclaimed imperial Mandarin as Guoyu (国语; 國語), the 'national language'.

Republican era

After the Republic of China was established in 1912, there was more success in promoting a common national language. A Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation was convened with delegates from the entire country.[35] A Dictionary of National Pronunciation (國音字典; 国音字典) was published in 1919, defining a hybrid pronunciation that did not match any existing speech.[36][37] Meanwhile, despite the lack of a workable standardized pronunciation, colloquial literature in written vernacular Chinese continued to develop.[38]

Gradually, the members of the National Language Commission came to settle upon the Beijing dialect, which became the major source of standard national pronunciation due to its prestigious status. In 1932, the commission published the Vocabulary of National Pronunciation for Everyday Use (國音常用字彙; 国音常用字汇), with little fanfare or official announcement. This dictionary was similar to the previous published one except that it normalized the pronunciations for all characters into the pronunciation of the Beijing dialect. Elements from other dialects continue to exist in the standard language, but as exceptions rather than the rule.[39]

Following the end of the Chinese Civil War, the People's Republic of China (PRC) continued standardisation efforts on the mainland, and in 1955 officially began using Putonghua (普通话; 普通話; 'common speech') instead of Guoyu, which remains the name used in Taiwan. The forms of Standard Chinese used in China and Taiwan have diverged somewhat since the end of the Civil War, especially in newer vocabulary, and a little in pronunciation.[40]

In 1956, the PRC officially defined Standard Chinese as "the standard form of Modern Chinese with the Beijing phonological system as its norm of pronunciation, and Northern dialects as its base dialect, and looking to exemplary modern works in written vernacular Chinese for its grammatical norms."[41][42] According to the official definition, Standard Chinese uses:

- The phonology of the Beijing dialect, if not always with each phoneme having the precise phonetic values as those heard in Beijing.

- The vocabulary of Mandarin dialects in general, excepting what are deemed to be slang and regionalisms. The vocabulary of all Chinese varieties, especially in more technical fields like science, law, and government, is very similar—akin to the profusion of Latin and Greek vocabulary in European languages. This means that much of the vocabulary of Standard Chinese is shared with all varieties of Chinese. Much of the colloquial vocabulary of the Beijing dialect is not considered part of Standard Chinese, and may not be understood by people outside Beijing.[43]

- The grammar and idioms of exemplary modern Chinese literature, a form known as written vernacular Chinese. Written vernacular Chinese is loosely based upon a synthesis of predominantly northern grammar and vocabulary, with southern and Literary elements. This distinguishes Standard Chinese from the dialect heard on the streets of Beijing.

Proficiency in the new standard was initially limited, even among Mandarin speakers, but increased over the following decades.[44]

| Early 1950s | 1984 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehension | Comprehension | Speaking | |

| Mandarin-speaking areas | 54 | 91 | 54 |

| non-Mandarin areas | 11 | 77 | 40 |

| whole country | 41 | 90 | 50 |

A 2007 survey conducted by the Chinese Ministry of Education indicated that 53.06% of the population were able to effectively communicate using Standard Chinese.[46] By 2020, this figure had risen to over 80%.[47]

Status

In both mainland China and Taiwan, Standard Chinese is used in most official contexts, as well as the media and educational system, contributing to its proliferation. As a result, it is now spoken by most people in both countries, though often with some regional or personal variation in vocabulary and pronunciation.

In overseas Chinese communities outside Asia where Cantonese once dominated, such as the Chinatown in Manhattan, the use of Standard Chinese, which is the primary lingua franca of more recent Chinese immigrants, is rapidly increasing.[48]

Mainland China

While Standard Chinese was made China's official language in the early 20th century, local languages continue to be the main form of everyday communication in much of the country. The language policy adopted by the Chinese government promotes the use of Standard Chinese while also making allowances for the use and preservation of local varieties.[49] From an official point of view, Standard Chinese serves as a lingua franca to facilitate communication between speakers of mutually unintelligible varieties of Chinese and non-Sinitic languages. The name Putonghua, or 'common speech', reinforces this idea. However, due to Standard Chinese being a "public" lingua franca, other Chinese varieties and even non-Sinitic languages have shown signs of losing ground to the standard dialect. In many areas, especially in southern China, it is commonly used for practical reasons, as linguistic diversity is so great that residents of neighboring cities may have difficulties communicating with each other without a lingua franca.

The Chinese government's language policy been largely successful, with over 80% of the Chinese population able to speak Standard Chinese as of 2020.[3] The Chinese government's current goal is to have 85% of the country's population speak Standard Chinese by 2025, and virtually the entire country by 2035.[50] Throughout the country, Standard Chinese has heavily influenced local languages through diglossia, replacing them entirely in some cases, especially among younger people in urban areas.[51]

The Chinese government is keen to promote Putonghua as the national lingua franca: under the National Common Language and Writing Law, the government is required to promoted its use. Officially, the Chinese government has not stated its intent to replace regional varieties with Standard Chinese. However, regulations enacted by local governments to implement the national law−such as the Guangdong National Language Regulations—have included coercive measures to control the public's use of both spoken dialects and traditional characters in writing. Some Chinese speakers who are older or from rural areas cannot speak Standard Chinese fluently or at all—though most are able to understand it. Meanwhile, those from urban areas—as well as younger speakers, who have received their education primarily in Standard Chinese—are almost all fluent in it, with some being unable to speak their local dialect.

The Chinese government has disseminated public service announcements promoting the use of Putonghua on television and the radio, as well as on public buses. The standardization campaign has been challenged by local dialectical and ethnic populations, who fear the loss of their cultural identity and native dialect. In the summer of 2010, reports of a planned increase in the use of the Putonghua on local television in Guangdong led to demonstrations on the streets by thousands of Cantonese-speaking citizens.[52] While the use of Standard Chinese is encouraged as the common working language in predominantly Han areas on the mainland, the PRC has been more sensitive to the status of non-Sinitic minority languages, and has generally not discouraged their social use outside of education.

Hong Kong and Macau

In Hong Kong and Macau, which are special administrative regions of the PRC, there is diglossia between Cantonese (口語; hau2 jyu5; 'spoken language') as the primary spoken language, alongside a local form of Standard Chinese (書面語; syu1 min6 jyu5; 'written language') used in schools, local government, and formal writing.[53] Written Cantonese may also be used in informal settings such as advertisements, magazines, popular literature, and comics. Mixture of formal and informal written Chinese occurs to various degrees.[54] After the Hong Kong's handover from the United Kingdom and Macau's handover from Portugal, their governments use Putonghua to communicate with the PRC's Central People's Government. There has been significant effort to promote use of Putonghua in Hong Kong since the handover,[55] including the training of police[56] and teachers.[57]

Taiwan

Standard Chinese is the official language of Taiwan. Standard Chinese started being widely spoken in Taiwan following the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, with the relocation of the Kuomintang (KMT) to the island along with an influx of refugees from the mainland. The Standard Chinese used in Taiwan differs very little from that of mainland China, with differences largely being in technical vocabulary introduced after 1949.[58]

Prior to 1949, the varieties most commonly spoken by Taiwan's Han population were Taiwanese Hokkien, as well as Hakka to a lesser extent. Much of the Taiwanese Aboriginal population spoke their native Formosan languages. During the period of martial law between 1949 and 1987, the Taiwanese government revived the Mandarin Promotion Council, discouraging or in some cases forbidding the use of Hokkien and other non-standard varieties. This resulted in Standard Chinese replacing Hokkien as the country's lingua franca,[59] and ultimately, a political backlash in the 1990s. Starting in the 2000s during the administration of President Chen Shui-Bian, the Taiwanese government began making efforts to recognize the country's other languages. They began being taught in schools, and their use increased in media, though Standard Chinese remains the country's lingua franca.[60] Chen often used Hokkien in his speeches; later Taiwanese President Lee Teng-hui also openly spoke Hokkien. In an amendment to the Enforcement Rules of the Passport Act (護照條例施行細則) passed on 9 August 2019, Taiwan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that romanized spellings of names in Hoklo, Hakka and Aboriginal languages may be used in Taiwanese passports. Previously, only Mandarin names could be romanized.[61]

Singapore

Mandarin is one of the four official languages of Singapore, along with English, Malay, and Tamil. Historically, it was seldom used by the Chinese Singaporean community, which primarily spoke the Southern Chinese languages of Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, or Hakka.[citation needed] Standard Singaporean Mandarin is nearly identical to the standards of China and Taiwan, with minor vocabulary differences. It is the Mandarin variant used in education, media, and official settings. Meanwhile, a colloquial form called Singdarin is used in informal daily life and is heavily influenced in terms of both grammar and vocabulary by local languages such as Cantonese, Hokkien, and Malay. Instances of code-switching with English, Hokkien, Cantonese, Malay, or a combination thereof are also common.

In Singapore, the government has heavily promoted a "Speak Mandarin Campaign" since the late 1970s, with the use of other Chinese varieties in broadcast media being prohibited and their use in any context officially discouraged until recently.[62] This has led to some resentment amongst the older generations, as Singapore's migrant Chinese community is made up almost entirely of people of south Chinese descent. Lee Kuan Yew, the initiator of the campaign, admitted that to most Chinese Singaporeans, Mandarin was a "stepmother tongue" rather than a true mother language. Nevertheless, he saw the need for a unified language among the Chinese community not biased in favor of any existing group.[63]

Malaysia

In Malaysia, Mandarin has been adopted by local Chinese-language schools as the medium of instruction with the standard shared with Singaporean Chinese. Together influenced by the Singaporean Speak Mandarin Campaign and Chinese culture revival movement in the 1980s, Malaysian Chinese started their own promotion of Mandarin too, and similar to Singapore, but to a lesser extent, experienced language shift from other Chinese variants to Mandarin. Today, Mandarin functions as lingua franca among Malaysian Chinese, while Hokkien and Cantonese are still retained in the northern part and central part of Peninsular Malaysia respectively.

Myanmar

In some regions controlled by insurgent groups in northern Myanmar, Mandarin serves as the lingua franca.[64]

Education

In both mainland China and Taiwan, Standard Chinese is taught by immersion starting in elementary school. After the second grade, the entire educational system is in Standard Chinese, except for local language classes that have been taught for a few hours each week in Taiwan starting in the mid-1990s.

With an increase in internal migration in China, the official Putonghua Proficiency Test (PSC) has become popular. Employers often require a level of Standard Chinese proficiency from applicants depending on the position, and many university graduates on the mainland take the PSC before looking for a job.

Phonology

The pronunciation of Standard Chinese is defined as that of the Beijing dialect.[65] The usual unit of analysis is the syllable, consisting of an optional initial consonant, an optional medial glide, a main vowel and an optional coda, and further distinguished by a tone.[66]

| Labial | Alveolar | Dental sibilant | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | |||||

| Stops and affricates |

unaspirated | p ⟨b⟩ | t ⟨d⟩ | t͡s ⟨z⟩ | ʈ͡ʂ ⟨zh⟩ | t͡ɕ ⟨j⟩ | k ⟨g⟩ |

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨p⟩ | tʰ ⟨t⟩ | t͡sʰ ⟨c⟩ | ʈ͡ʂʰ ⟨ch⟩ | t͡ɕʰ ⟨q⟩ | kʰ ⟨k⟩ | |

| Fricatives | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | ʂ ⟨sh⟩ | ɕ ⟨x⟩ | x ⟨h⟩ | ||

| Approximants | w ⟨w⟩ | l ⟨l⟩ | ɻ~ʐ ⟨r⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | |||

The palatal initials [tɕ], [tɕʰ] and [ɕ] pose a classic problem of phonemic analysis. Since they occur only before high front vowels, they are in complementary distribution with three other series, the dental sibilants, retroflexes and velars, which never occur in this position.[68]

| ɹ̩ ⟨i⟩ | ɤ ⟨e⟩ | a ⟨a⟩ | ei ⟨ei⟩ | ai ⟨ai⟩ | ou ⟨ou⟩ | au ⟨ao⟩ | ən ⟨en⟩ | an ⟨an⟩ | əŋ ⟨eng⟩ | aŋ ⟨ang⟩ | ɚ ⟨er⟩ |

| i ⟨i⟩ | ie ⟨ie⟩ | ia ⟨ia⟩ | iou ⟨iu⟩ | iau ⟨iao⟩ | in ⟨in⟩ | ien ⟨ian⟩ | iŋ ⟨ing⟩ | iaŋ ⟨iang⟩ | |||

| u ⟨u⟩ | uo ⟨uo⟩ | ua ⟨ua⟩ | uei ⟨ui⟩ | uai ⟨uai⟩ | uən ⟨un⟩ | uan ⟨uan⟩ | uŋ ⟨ong⟩ | uaŋ ⟨uang⟩ | |||

| y ⟨ü⟩ | ye ⟨üe⟩ | yn ⟨un⟩ | yen ⟨uan⟩ | iuŋ ⟨iong⟩ |

The [ɹ̩] final, which occurs only after dental sibilant and retroflex initials, is a syllabic approximant, prolonging the initial.[70][71]

The rhotacized vowel [ɚ] forms a complete syllable.[72] A reduced form of this syllable occurs as a sub-syllabic suffix, spelled -r in pinyin and often with a diminutive connotation. The suffix modifies the coda of the base syllable in a rhotacizing process called erhua.[73]

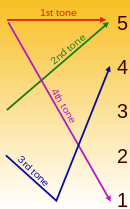

Each full syllable is pronounced with a phonemically distinctive pitch contour. There are four tonal categories, marked in pinyin with diacritics, as in the words mā (媽; 妈; 'mother'), má (麻; 'hemp'), mǎ (馬; 马; 'horse') and mà (罵; 骂; 'curse').[74] The tonal categories also have secondary characteristics. For example, the third tone is long and murmured, whereas the fourth tone is relatively short.[75][76] Statistically, vowels and tones are of similar importance in the language.[a][78]

There are also weak syllables, including grammatical particles such as the interrogative ma (嗎; 吗) and certain syllables in polysyllabic words. These syllables are short, with their pitch determined by the preceding syllable.[79] Such syllables are commonly described as being in the neutral tone.

Regional accents

It is common for Standard Chinese to be spoken with the speaker's regional accent, depending on factors such as age, level of education, and the need and frequency to speak in official or formal situations.

Due to evolution and standardization, Mandarin, although based on the Beijing dialect, is no longer synonymous with it. Part of this was due to the standardization to reflect a greater vocabulary scheme and a more archaic and "proper-sounding" pronunciation and vocabulary.

Distinctive features of the Beijing dialect are more extensive use of erhua in vocabulary items that are left unadorned in descriptions of the standard such as the Xiandai Hanyu Cidian, as well as more neutral tones.[80] An example of standard versus Beijing dialect would be the standard mén (door) and Beijing ménr.

While the Standard Chinese spoken in Taiwan is nearly identical to that of mainland China, the colloquial form has been heavily influenced by other local languages, especially Taiwanese Hokkien. Notable differences include: the merger of retroflex sounds (zh, ch, sh, r) with the alveolar series (z, c, s), frequent mergers of the "neutral tone" with a word's original tone, and absence of erhua.[81] Code-switching between Mandarin and Taiwanese Hokkien is common, as the majority of the population continues to also speak the latter as a native language.[82]

The stereotypical "southern Chinese" accent does not distinguish between retroflex and alveolar consonants, pronouncing pinyin zh [tʂ], ch [tʂʰ], and sh [ʂ] in the same way as z [ts], c [tsʰ], and s [s] respectively.[83] Southern-accented Standard Chinese may also interchange l and n, final n and ng, and vowels i and ü [y]. Attitudes towards southern accents, particularly the Cantonese accent, range from disdain to admiration.[84]

Grammar

Chinese is a strongly analytic language, having almost no inflectional morphemes, and relying on word order and particles to express relationships between the parts of a sentence.[85] Nouns are not marked for case and rarely marked for number.[86] Verbs are not marked for agreement or grammatical tense, but aspect is marked using post-verbal particles.[87]

The basic word order is subject–verb–object (SVO), as in English.[88] Nouns are generally preceded by any modifiers (adjectives, possessives and relative clauses), and verbs also generally follow any modifiers (adverbs, auxiliary verbs and prepositional phrases).[89]

他

Tā

He

为/為

wèi

for

他的

tā-de

he-GEN

朋友

péngyǒu

friend

做了

zuò-le

do-PERF

这个/這個

zhè-ge

this-CL

工作。

gōngzuò.

job

'He did this job for his friends.'[90]

The predicate can be an intransitive verb, a transitive verb followed by a direct object, a copula (linking verb) shì (是) followed by a noun phrase, etc.[91]

In predicative use, Chinese adjectives function as stative verbs, forming complete predicates in their own right without a copula.[92] For example,

我

Wǒ

I

不

bú

not

累。

lèi.

tired

'I am not tired.'

Chinese additionally differs from English in that it forms another kind of sentence by stating a topic and following it by a comment.[93] To do this in English, speakers generally flag the topic of a sentence by prefacing it with "as for". For example:

妈妈/媽媽

Māma

Mom

给/給

gěi

give

我们/我們

wǒmen

us

的

de

REL

钱/錢,

qián,

money

我

wǒ

I

已经/已經

yǐjīng

already

买了/買了

mǎi-le

buy-PERF

糖果。

tángguǒ(r)

candy

'As for the money that Mom gave us, I have already bought candy with it.'

The time when something happens can be given by an explicit term such as "yesterday", by relative terms such as "formerly", etc.[94]

As in many east Asian languages, classifiers or measure words are required when using numerals, demonstratives and similar quantifiers.[95] There are many different classifiers in the language, and each noun generally has a particular classifier associated with it.[96]

一顶

yī-dǐng

one-top

帽子,

màozi,

hat

三本

sān-běn

three-volume

书/書,

shū,

book

那支

nèi-zhī

that-branch

笔/筆

bǐ

pen

'a hat, three books, that pen'

The general classifier ge (个/個) is gradually replacing specific classifiers.[97]

In word formation, the language allows for compounds and for reduplication.

Vocabulary

Many honorifics used in imperial China are also used in daily conversation in modern Mandarin, such as jiàn (賤; 贱; '[my] humble') and guì (貴; 贵; '[your] honorable').

Although Chinese speakers make a clear distinction between Standard Chinese and the Beijing dialect, there are aspects of Beijing dialect that have made it into the official standard. Standard Chinese has a T–V distinction between the polite and informal "you" that comes from the Beijing dialect, although its use is quite diminished in daily speech. It also distinguishes between "zánmen" ('we', including the listener) and "wǒmen" ('we', not including the listener). In practice, neither distinction is commonly used by most Chinese, at least outside the Beijing area.

The following samples are some phrases from the Beijing dialect which are not yet accepted into Standard Chinese:[citation needed]

- 倍儿 bèir means 'very much'; 拌蒜 bànsuàn means 'stagger'; 不吝 bù lìn means 'do not worry about'; 撮 cuō means 'eat'; 出溜 chūliū means 'slip'; (大)老爷儿们儿 dà lǎoyermenr means 'man, male'.

The following samples are some phrases from Beijing dialect which have become accepted as Standard Chinese:[citation needed]

- 二把刀 èr bǎ dāo means 'not very skillful'; 哥们儿 gēménr means 'good male friend', 'buddy'; 抠门儿 kōu ménr means 'frugal' or 'stingy'.

Writing system

Standard Chinese is written with characters corresponding to syllables of the language, most of which represent a morpheme. In most cases, these characters come from those used in Classical Chinese to write cognate morphemes of late Old Chinese, though their pronunciation, and often meaning, has shifted dramatically over two millennia.[98] However, there are several words, many of them heavily used, which have no classical counterpart or whose etymology is obscure. Two strategies have been used to write such words:[99]

- An unrelated character with the same or similar pronunciation might be used, especially if its original sense was no longer common. For example, the demonstrative pronouns zhè 'this' and nà 'that' have no counterparts in Classical Chinese, which used 此 cǐ and 彼 bǐ respectively. Hence the character 這 (later simplified as 这) for zhè 'to meet' was borrowed to write zhè 'this', and the character 那 for nà, the name of a country and later a rare surname, was borrowed to write nà 'that'.

- A new character, usually a phono-semantic or semantic compound, might be created. For example, gǎn 'pursue', 'overtake', is written with a new character 趕, composed of the signific 走 zǒu 'run' and the phonetic 旱 hàn 'drought'.[100] This method was used to represent many elements in the periodic table.

The PRC, as well as several other governments and institutions, has promulgated a set of simplified character forms. Under this system, the forms of the words zhèlǐ ('here') and nàlǐ ('there') changed from 這裏/這裡 and 那裏/那裡 to 这里 and 那里, among many other changes.

Chinese characters were traditionally read from top to bottom, right to left, but in modern usage it is more common to read from left to right.

Examples

| English | Traditional characters | Simplified characters | Pinyin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hello! | 你好! | Nǐ hǎo! | |

| What is your name? | 你叫什麼名字? | 你叫什么名字? | Nǐ jiào shénme míngzi? |

| My name is... | 我叫... | Wǒ jiào ... | |

| How are you? | 你好嗎?/ 你怎麼樣? | 你好吗?/ 你怎么样? | Nǐ hǎo ma? / Nǐ zěnmeyàng? |

| I am fine, how about you? | 我很好,你呢? | Wǒ hěn hǎo, nǐ ne? | |

| I don't want it / I don't want to | 我不要。 | Wǒ bú yào. | |

| Thank you! | 謝謝! | 谢谢! | Xièxie |

| Welcome! / You're welcome! (Literally: No need to thank me!) / Don't mention it! (Literally: Don't be so polite!) | 歡迎!/ 不用謝!/ 不客氣! | 欢迎!/ 不用谢!/ 不客气! | Huānyíng! / Búyòng xiè! / Bú kèqì! |

| Yes. / Correct. | 是。 / 對。/ 嗯。 | 是。 / 对。/ 嗯。 | Shì. / Duì. / M. |

| No. / Incorrect. | 不是。/ 不對。/ 不。 | 不是。/ 不对。/ 不。 | Búshì. / Bú duì. / Bù. |

| When? | 什麼時候? | 什么时候? | Shénme shíhou? |

| How much money? | 多少錢? | 多少钱? | Duōshǎo qián? |

| Can you speak a little slower? | 您能說得再慢些嗎? | 您能说得再慢些吗? | Nín néng shuō de zài mànxiē ma? |

| Good morning! / Good morning! | 早上好! / 早安! | Zǎoshang hǎo! / Zǎo'ān! | |

| Goodbye! | 再見! | 再见! | Zàijiàn! |

| How do you get to the airport? | 去機場怎麼走? | 去机场怎么走? | Qù jīchǎng zěnme zǒu? |

| I want to fly to London on the eighteenth | 我想18號坐飛機到倫敦。 | 我想18号坐飞机到伦敦。 | Wǒ xiǎng shíbā hào zuò fēijī dào Lúndūn. |

| How much will it cost to get to Munich? | 到慕尼黑要多少錢? | 到慕尼黑要多少钱? | Dào Mùníhēi yào duōshǎo qián? |

| I don't speak Chinese very well. | 我的漢語說得不太好。 | 我的汉语说得不太好。 | Wǒ de Hànyǔ shuō de bú tài hǎo. |

| Do you speak English? | 你會說英語嗎? | 你会说英语吗? | Nǐ huì shuō Yīngyǔ ma? |

| I have no money. | 我沒有錢。 | 我没有钱。 | Wǒ méiyǒu qián. |

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Standard Chinese:[101]

人人生而自由,在尊严和权利上一律平等。他们赋有理性和良心,并应以兄弟关系的精神相对待。

人人生而自由,在尊嚴和權利上一律平等。他們賦有理性和良心,並應以兄弟關係的精神相對待。

Rén rén shēng ér zìyóu, zài zūnyán hé quánlì shàng yīlǜ píngděng. Tāmen fùyǒu lǐxìng hé liángxīn, bìng yīng yǐ xiōngdì guānxì de jīngshén xiāng duìdài.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

See also

- Chinese speech synthesis

- Comparison of national standards of Chinese

- Mandarin Chinese in the Philippines

- Protection of the varieties of Chinese

- Chinese language law

- Yayan

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 251.

- ^ Liang (2014), p. 45.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Over 80 percent of Chinese population speak Mandarin", People's Daily, retrieved 22 December 2021

- ^ Tai, James; Tsay, Jane (2015), Sign Languages of the World: A Comparative Handbook, Walter de Gruyter, p. 772, ISBN 9781614518174, retrieved 26 February 2020

- ^ Adamson, Bob; Feng, Anwei (27 December 2021), Multilingual China: National, Minority and Foreign Languages, Routledge, p. 90, ISBN 978-1-000-48702-2,

Despite not being defined as such in the Constitution, Putonghua enjoys de facto status of the official language in China and is legislated as the standard form of Chinese.

- ^ http://www.china-language.gov.cn/ Archived 18 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine (Chinese)

- ^ Bradley (1992), p. 307.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rohsenow, John S. (2004), "Fifty Years of Script and Written Language Reform in the P.R.C.", in Zhou, Minglang (ed.), Language Policy in the People's Republic of China, Springer, pp. 22, 24, ISBN 9781402080395,

accurately represent and express the sounds of standard Northern Mandarin (Putonghua) [...]. Central to the promotion of Putonghua as a national language with a standard pronunciation as well as to assisting literacy in the non-phonetic writing system of Chinese characters was the development of a system of phonetic symbols with which to convey the pronunciation of spoken words and written characters in standard northern Mandarin.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ran, Yunyun; Weijer, Jeroen van de (2016), "On L2 English Intonation Patterns by Mandarin and Shanghainese Speakers: A Pilot Study", in Sloos, Marjoleine; Weijer, Jeroen van de (eds.), Proceedings of the second workshop "Chinese Accents and Accented Chinese" (2nd CAAC) 2016, at the Nordic Center, Fudan University, Shanghai, 26-27 October 2015 (PDF), p. 4, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2016,

We recorded a number of English sentences spoken by speakers with Mandarin Chinese (standard northern Mandarin) as their first language and by Chinese speakers with Shanghainese as their first language, [...]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bradley, David (2008), "Chapter 5: East and Southeast Asia", in Moseley, Christopher (ed.), Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages, Routledge, p. 500 (e-book), ISBN 9781135796402,

As a result of the spread of standard northern Mandarin and major regional varieties of provincial capitals since 1950, many of the smaller tuyu [土語] are disappearing by being absorbed into larger regional fangyan [方言], which of course may be a sub-variety of Mandarin or something else.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Siegel, Jeff (2003), "Chapter 8: Social Context", in Doughty, Catherine J.; Long, Michael H. (eds.), The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition, Blackwell Publishing, U.K., p. 201, ISBN 9781405151887,

Escure [Geneviève Escure, 1997] goes on to analyse second dialect texts of Putonghua (standard Beijing Mandarin Chinese) produced by speakers of other varieties of Chinese, [in] Wuhan and Suzhou.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chen, Ying-Chuan (2013). Becoming Taiwanese: Negotiating Language, Culture and Identity (PDF) (Thesis). University of Ottawa. p. 300. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2020.

[...] a consistent gender pattern found across all the age cohorts is that women were more concerned about their teachers' bad Mandarin pronunciation, and implied that it was an inferior form of Mandarin, which signified their aspiration to speak standard Beijing Mandarin, the good version of the language.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Weng, Jeffrey (2018), "What is Mandarin? The social project of language standardization in early Republican China", The Journal of Asian Studies, 59 (1): 611–633, doi:10.1017/S0021911818000487,

in common usage, 'Mandarin' or 'Mandarin Chinese' usually refers to China's standard spoken language. In fact, I would argue that this is the predominant meaning of the word

- ^ Sanders, Robert M. (1987), "The Four Languages of "Mandarin"" (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, no. 4, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2012

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 136.

- ^ "Mandarin", Oxford Dictionary, archived from the original on 3 July 2020

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mair (2013), p. 737.

- ^ Mair (1991), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Coblin (2000), p. 537.

- ^ 张杰 (2012), "论清代满族语言文字在东北的兴废与影响", in 张杰 (ed.), 清文化与满族精神 (in Chinese), 辽宁民族出版社, archived from the original on 5 November 2020,

[天聪五年, 1631年] 满大臣不解汉语,故每部设启心郎一员,以通晓国语之汉员为之,职正三品,每遇议事,座在其中参预之。

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tam (2020), p. 76.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 133–134.

- ^ Cao Dehe (曹德和) (2011), 恢复"国语名"称的建议为何不被接受_──《国家通用语言文字法》学习中的探讨和思考 (in Chinese), Tribune of Social Sciences

- ^ Yuan, Zhongrui. (2008) "国语、普通话、华语 Archived 26 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine (Guoyu, Putonghua, Huayu)". China Language National Language Committee, People's Republic of China

- ^ Sponsored by Council of Indigenous Peoples (14 June 2017), 原住民族語言發展法 [Indigenous Languages Development Act], Laws & Regulations Database of The Republic of China, the Ministry of Justice,

Indigenous languages are national languages. To carry out historical justice, promote the preservation and development of indigenous languages, and secure indigenous language usage and heritage, this act is enacted according to... [原住民族語言為國家語言,為實現歷史正義,促進原住民族語言之保存與發展,保障原住民族語言之使用及傳承,依...]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wang Baojian (王保鍵) (2018), 客家基本法之制定與發展:兼論 2018 年修法重點 (PDF), Journal of Civil Service, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 89, 92–96, archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2020

- ^ Sponsored by Hakka Affairs Council (31 January 2018), 客家基本法 [Hakka Basic Act], Laws & Regulations Database of The Republic of China, the Ministry of Justice,

Hakka language is one of the national languages, equal to the languages of other ethnic groups. The people shall be given guarantee on their right to study in Hakka language and use it in enjoying public services and partaking of the dissemination of resources. [客語為國家語言之一,與各族群語言平等。人民以客語作為學習語言、接近使用公共服務及傳播資源等權利,應予保障。]

- ^ Mair (1991), pp. 11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Xu Weixian (許維賢) (2018), 華語電影在後馬來西亞:土腔風格、華夷風與作者論 [Chinese films in Malaysia: local and overseas styles and auteur theory] (in Chinese), Lianjing chuban, pp. 36–41, ISBN 978-9-570-85098-7

- ^ Kane, Daniel (2006), The Chinese Language: Its History and Current Usage, Tuttle Publishing, pp. 22–23, 93, ISBN 978-0-8048-3853-5

- ^ Fourmont, Étienne (1742), Linguæ Sinarum Mandarinicæ Hieroglyphicæ Grammatica Duplex [Grammar of the Mandarin Chinese Hieroglyphics] (in Latin), Paris: Hippolyte-Louis Guérin

- ^ Translation quoted in Coblin (2000), p. 539

- ^ Coblin (2000), pp. 549–550.

- ^ Richard, Louis; Kennelly, M. (1908), Comprehensive geography of the Chinese empire and dependencies, Shanghai: Tusewei Press, p. iv, retrieved 6 March 2024

- ^ Chen (1999), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 134.

- ^ Chen (1999), p. 18.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 10.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 15.

- ^ Bradley (1992), pp. 313–314.

- ^ Law of the People's Republic of China on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language (Order of the President No.37), Gov.cn, 31 October 2000, archived from the original on 24 July 2013, retrieved 27 April 2010, 普通话就是现代汉民族共同语,是全国各民族通用的语言。普通话以北京语音为标准音,以北方话为基础方言,以典范的现代白话文著作语法规范 [For purposes of this Law, the standard spoken and written Chinese language means Putonghua (a common speech with pronunciation based on the Beijing dialect) and the standardized Chinese characters.]

- ^ Chen (1999), p. 24.

- ^ Chen (1999), pp. 37–38.

- ^ Chen (1999), pp. 27–28.

- ^ Chen (1999), p. 28.

- ^ More than half of Chinese can speak Mandarin, Xinhua, 7 March 2007

- ^ E'nuo, Zhao; Wu, Yue (16 October 2020), "Over 80 percent of Chinese population speak Mandarin", People's Daily

- ^ Semple, Kirk (21 October 2009), "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin", The New York Times, archived from the original on 14 July 2011, retrieved 18 July 2011

- ^ Spolsky, Bernard (December 2014), "Language management in the People's Republic of China" (PDF), Linguistic Society of America, vol. 90, p. 168

- ^ "China says 85% of citizens will use Mandarin by 2025", ABC News, retrieved 22 December 2021

- ^ Zuo, Xinyi (16 December 2020), "Effects of Ways of Communication on the Preservation of Shanghai Dialect", Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2020), Atlantis Press, pp. 56–59, doi:10.2991/assehr.k.201214.465, ISBN 978-94-6239-301-1, S2CID 234515573

- ^ Luo, Chris (23 September 2014), "One-third of Chinese do not speak Putonghua, says Education Ministry", South China Morning Post, Hong Kong, archived from the original on 2 June 2015, retrieved 18 September 2017

- ^ Lee, Siu-lun (2023), The Learning and Teaching of Cantonese as a Second Language, Abingdon/New York: Routledge, ISBN 9781000889895

- ^ Shi, Dingxu (12 October 2006), "Hong Kong written Chinese: Language change induced by language contact", Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 16 (2): 299–318, doi:10.1075/japc.16.2.09shi, S2CID 143191355

- ^ Standing Committee on Language Education & Research (25 March 2006), Putonghua promotion stepped up, Hong Kong Government, archived from the original on 21 July 2011, retrieved 12 February 2011

- ^ Online training to boost Chinese skills, Hong Kong Police Department, archived from the original on 21 July 2011, retrieved 12 February 2011

- ^ Hong Kong LegCo (19 April 1999), Panel on Education working reports, Hong Kong Government, archived from the original on 21 July 2011, retrieved 12 February 2011

- ^ Yao, Qian (September 2014), "Analysis of Computer Terminology Translation Differences between Taiwan and Mainland China", Advanced Materials Research, 1030–1032: 1650–1652, doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1030-1032.1650, S2CID 136508776

- ^ Scott & Tiun (2007), p. 57.

- ^ Hubbs, Elizabeth, "Taiwan language-in-education policy: social, cultural and practical implications", Arizona Working Papers in SLA & Teaching, vol. 20, pp. 76–95

- ^ Jason Pan (16 August 2019), "NTU professors' language rule draws groups' ire", Taipei Times, archived from the original on 17 August 2019, retrieved 17 August 2019

- ^ "New Hokkien drama aimed at seniors to be launched on Sep 9", Channel News Asia, 1 September 2016, archived from the original on 19 December 2016

- ^ Yew, Lee Kuan (3 October 2000), From Third World to First: The Singapore Story: 1965-2000, Harper Collins, ISBN 978-0-06-019776-6, OL 7275961M

- ^ Aung Thein Kha; Gerin, Roseanne (17 September 2019), "In Myanmar's Remote Mongla Region, Mandarin Supplants The Burmese Language", Radio Free Asia, retrieved 31 May 2020

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 138.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 138–139.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 139.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 140–141.

- ^ Lee & Zee (2003), p. 110.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 142.

- ^ Lee & Zee (2003), p. 111.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 143–144.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 144–145.

- ^ Duanmu (2007), p. 225.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 147.

- ^ Duanmu (2007), p. 236.

- ^ Chao (1948), p. 24.

- ^ Surendran, Dinoj; Levow, Gina-Anne (2004), "The functional load of tone in Mandarin is as high as that of vowels" (PDF), in Bel, Bernard; Marlien, Isabelle (eds.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Speech Prosody 2004, SProSIG, pp. 99–102, ISBN 978-2-9518233-1-0, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2007

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 148.

- ^ Chen (1999), pp. 39–40.

- ^ Chen (1999), p. 47.

- ^ Chiu, Miao-chin (April 2012), "Code-switching and Identity Constructions in Taiwan TV Commercials" (PDF), Monumenta Taiwanica, vol. 5, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2020, retrieved 24 May 2020

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 140.

- ^ Blum, Susan D. (2002), "Ethnic and Linguistic Diversity in Kunming", in Blum, Susan Debra; Jensen, Lionel M (eds.), China Off Center: Mapping the Margins of the Middle Kingdom, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 160–161, ISBN 978-0-8248-2577-5

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 159.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Lin (1981), p. 19.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), pp. 24–26.

- ^ Lin (1981), p. 169.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), p. 141.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), pp. 141–143.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), pp. 15–16.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), pp. 320–320.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), p. 104.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), p. 105.

- ^ Li & Thompson (1981), p. 112.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 74.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 74–75.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 76.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights - Chinese, Mandarin (Simplified)", unicode.org, archived from the original on 19 January 2022, retrieved 11 January 2022"Universal Declaration of Human Rights - Chinese, Mandarin (Simplified)", unicode.org, archived from the original on 19 January 2022, retrieved 11 January 2022Nations, United, "Universal Declaration of Human Rights", United Nations

Works cited

- Adelaar, K. Alexander (1996), "Contact languages in Indonesia and Malaysia other than Malay", in Wurm, Stephen A.; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tryon, Darrell T. (eds.), Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Vol II: Texts, de Gruyter Mouton, pp. 695–711, doi:10.1515/9783110819724, ISBN 978-3-11-081972-4.

- Bradley, David (1992), "Chinese as a pluricentric language", in Clyne, Michael G. (ed.), Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 305–324, ISBN 978-3-11-012855-0.

- Chao, Yuen Ren (1948), Mandarin Primer: an Intensive Course in Spoken Chinese, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-73288-9.

- Chen, Ping (1999), Modern Chinese: History and sociolinguistics, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-64572-0.

- Coblin, W. South (2000), "A brief history of Mandarin", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 120 (4): 537–552, doi:10.2307/606615, JSTOR 606615.

- Duanmu, San (2007), The phonology of standard Chinese (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-921579-9.

- Lee, Wai-Sum; Zee, Eric (2003), "Standard Chinese (Beijing)", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33 (1): 109–112, doi:10.1017/S0025100303001208.

- Li, Charles N.; Thompson, Sandra A. (1981), Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06610-6.

- Li, Yuming (2015), Language Planning in China, Language Policies and Practices in China, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-1-61451-558-6

- Liang, Sihua (2014), Language Attitudes and Identities in Multilingual China: A Linguistic Ethnography, Springer International, ISBN 978-3-319-12618-0.

- Lin, Helen T. (1981), Essential Grammar for Modern Chinese, Boston: Cheng & Tsui, ISBN 978-0-917056-10-9.

- Mair, Victor H. (1991), "What Is a Chinese "Dialect/Topolect"? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic terms" (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, 29: 1–31, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2018, retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ——— (2013), "The Classification of Sinitic Languages: What Is "Chinese"?" (PDF), in Cao, Guangshun; Djamouri, Redouane; Chappell, Hilary; Wiebusch, Thekla (eds.), Breaking Down the Barriers: Interdisciplinary Studies in Chinese Linguistics and Beyond, Beijing: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, pp. 735–754, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2018, retrieved 15 April 2018.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The languages of China, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-01468-5.

- Scott, Mandy; Tiun, Hak-khiam (2007), "Mandarin-Only to Mandarin-Plus: Taiwan", Language Policy, 6 (1): 53–72, doi:10.1007/s10993-006-9040-5, S2CID 145009251.

- Tam, Gina Anne (2020), Dialect and Nationalism in China, 1860–1960, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-108-77640-0.

- Wang, Xiaomei (2012), Mandarin Spread in Malaysia, The University of Malaya Press, ISBN 978-983-100-958-1.

Further reading

- Chao, Yuen Ren (1968), A Grammar of Spoken Chinese (2nd ed.), University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-00219-7

- Hsia, T., China's Language Reforms, Far Eastern Publications, Yale University, (New Haven), 1956.

- Ladefoged, Peter; & Maddieson, Ian (1996). The sounds of the world's languages. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-19814-7 (hbk); ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4 (pbk).

- Ladefoged, Peter; Wu, Zhongji (1984), "Places of articulation: An investigation of Pekingese fricatives and affricates", Journal of Phonetics, 12 (3): 267–278, doi:10.1016/S0095-4470(19)30883-6

- Lehmann, W. P. (ed.), Language & Linguistics in the People's Republic of China, University of Texas Press, (Austin), 1975.

- Le, Wai-Sum; Zee, Eric (2003). "Standard Chinese (Beijing)". Illustrations of the IPA. Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 33 (1): 109–112. doi:10.1017/S0025100303001208, with supplementary sound recordings.

- Lin, Y., Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1972.

- Milsky, C., "New Developments in Language Reform", The China Quarterly, No. 53, (January–March 1973), pp. 98–133.

- Seybolt, P. J. and Chiang, G. K. (eds.), Language Reform in China: Documents and Commentary, M. E. Sharpe (White Plains), 1979. ISBN 978-0-87332-081-8.

- Simon, W., A Beginners' Chinese-English Dictionary of the National Language (Gwoyeu): Fourth Revised Edition, Lund Humphries (London), 1975.

- Weng, Jeffrey (2018), "What Is Mandarin? The Social Project of Language Standardization in Early Republican China", The Journal of Asian Studies, 77 (3): 611–633, doi:10.1017/S0021911818000487, S2CID 166176089

External links

Chinese (Mandarin) at Wikibooks

Chinese (Mandarin) at Wikibooks Standard Chinese travel guide from Wikivoyage

Standard Chinese travel guide from Wikivoyage- Video A History of Mandarin: China's Search for a Common Language, NYU Shanghai, 23 February 2018 - Talk by David Moser