Piero Manzoni

Piero Manzoni | |

|---|---|

Manzoni in 1960 | |

| Born | Piero Meroni Manzoni di Chiosca e Poggiolo July 13, 1933 |

| Died | February 6, 1963 (aged 29) Milan, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Artist |

| Notable work | Artist's Shit |

| Movement | Conceptual art |

Piero Manzoni di Chiosca e Poggiolo, better known as Piero Manzoni (July 13, 1933 – February 6, 1963) was an Italian artist best known for his ironic approach to avant-garde art. Often compared to the work of Yves Klein, his own work anticipated, and directly influenced, the work of a generation of younger Italian artists brought together by the critic Germano Celant in the first Arte Povera exhibition held in Genoa, 1967.[1] Manzoni is most famous for a series of artworks that call into question the nature of the art object, directly prefiguring Conceptual Art.[2][3] His work eschews normal artist's materials, instead using everything from rabbit fur to human excrement in order to "tap mythological sources and to realize authentic and universal values".[2]

His work is widely seen as a critique of the mass production and consumerism that was changing Italian society (the Italian economic miracle) after World War II.[4] Italian artists such as Manzoni had to negotiate the new economic and material order of post-war Europe through inventive artistic practices which crossed geographic, artistic, and cultural borders.

Manzoni died of myocardial infarction in his studio in Milan on February 6, 1963. His contemporary Ben Vautier signed Manzoni's death certificate, declaring it a work of art.[5]

Biography

[edit]Manzoni was born in Soncino, province of Cremona as the eldest of five children of Egisto Manzoni and Valeria Meroni. His full name was Count Meroni Manzoni di Chiosca e Poggiolo.[6] Through his sister Elena he was the uncle of the artist Pippa Bacca.

Self-taught as an artist, Manzoni first exhibited at the Soncino's Castle in Soncino in August 1956, at the age of 23. His early work was broadly gestural, and showed the influence of Milanese proponents of Nuclear Art, such as Enrico Baj.[7] His later works, from approximately 1957 until his death in 1963, questioned and satirized the status of the art object as it had been conceived throughout modernism. Influences include earlier (though still active) artists like Marcel Duchamp and contemporaneous practitioners Ben Vautier and Yves Klein.[5]

Achromes

[edit]

Manzoni's work changed irrevocably after visiting Yves Klein's exhibition 'Epoca Blu' at the Galleria Apollinaire in Milan, January 1957.[8] This exhibition consisted of 11 identical blue monochromes. By the end of the year he had ceased producing work influenced by the prevailing trends in Art Informel, to works that responded directly to Klein's monochromes.[9] Called Achromes, they invariably looked white but were actually colourless. In these paintings Manzoni experimented with various pigments and materials. Initially favouring canvases coated in gesso (1957–1958), he also worked with kaolin, another form of white clay often used in the production of porcelain.[10] The kaolin works are generally made from clay covered canvases folded horizontally, or sometimes cut-out squares of canvas coated in the clay and adhered onto the canvas; he created just nine large-scale relief paintings depicting folded cloth.[11] As well as Yves Klein, these works showed the influence of Lucio Fontana and Alberto Burri and the American artist Robert Rauschenberg, who had painted neutral white canvases in 1951.[12] Later he would create Achromes from white cotton wool, fiberglass, rabbit skin and bread rolls. He also experimented with phosphorescent paint and cobalt chloride so that the colours would change over time.

Azimut Gallery

[edit]Manzoni founded the Azimut Gallery in Milan in 1959 with the artist Enrico Castellani, and staged a series of revolutionary exhibitions of multiples. The first, 12 Linee (12 Lines) took place in December 1959, quickly followed by Corpi d'Aria (Bodies of Air) in May 1960.[13] This was an edition of 45 balloons on tripods that could be blown up by the buyer, or the artist himself, depending on the price paid. In July 1960 he exhibited Consumption of Art by the Art-Devouring Public, in which he hard-boiled 70 eggs, printed his thumbprint onto them, and after eating several himself handed them out to the audience to eat. The eggs themselves were titled Uova con impronta (Egg With Thumbprint). This was the last exhibition by Manzoni at Azimuth, after which the gallery was forced to close when the lease ran out. Although the invitation named the Gallery Azimuth as the location of the opening, the actual event took place at the Studio Filmgiornale Sedi in Milan. The discrepancy between the location on the invitation and the film studio where the event was recorded further complicates the role and space of art as it was expected to be seen.[5]

Artist's Breath

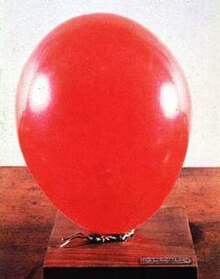

[edit]Contemporaneously with the Bodies of Air (Corpi D'Aria), Manzoni produced the Artist's Breaths (Fiato d'Artista), a series of red, white or blue balloons, inflated and attached to a wooden base inscribed "Piero Manzoni- Artist's Breath". The works continued Manzoni's obsession with the limits of physicality, whilst parodying the Art World's obsession with permanence, and also provided a poignant Memento Mori.

Artist's Shit

[edit]In May 1961 Manzoni created 90 small cans, sealed with the text Artist's Shit (Merda d'Artista). Each 30-gram can was priced by weight based on the current value of gold (around $1.12 a gram in 1960).[14] The contents of the cans remain a much-disputed enigma, since opening them would destroy the value of the artwork. Various theories about the contents have been proposed, including speculation that it is plaster.[15] In the following years, the cans have spread to various art collections all over the world and netted large prices, far outstripping inflation. A tin was sold for € 124,000 at Sotheby's on May 23, 2007; in October 2008 tin 83 was offered for sale at Sotheby's with an estimate of £ 50–70,000. It sold for £97,250.[16] It was described as:

"It is a joke, a parody of the art market, and a critique of consumerism and the waste it generates."

— Stephen Bury [17]

On October 16, 2015, tin 54 was sold at Christies for the astonishing sum of £182,500. The tins were originally to be valued according to their equivalent weight in gold – $37 each in 1961 – with the price fluctuating according to the market.

Other works from this period include limited edition thumbprints, and the Declarations of Authenticity, 1961-61, a printed multiple that could be bought, proving the owner's status as either part or whole work of art, depending on the price paid. He also designated a number of people, including Umberto Eco, as authentic works of art gratis. Various other experimental pieces by Manzoni included trying to create a mechanical animal as a moving sculpture and using solar energy as a power source. In 1960 he created a sphere that was held aloft on a jet of air.

Other works

[edit]- Magic Bases (Magisk Sockkel, 1961), a series of wooden plinths that could be stood on to acquire status of 'Living Sculpture'.

- Lines of Exceptional Length (1960–61). Lines drawn on paper, the longest of which was 7.2 km, intended to be left in every major city in the world, which would equal the length of the equator when joined.

- Base of the World (Socle du Monde, 1961). A large metal plinth, inscribed 'The Base Of The World, Homage To Galileo' placed upside down in a field in Herning, Denmark. It announces that the whole world is a work of art, rendering the artist obsolete.

- Piero Manzoni; The Life And Works (1963), published posthumously by Jes Petersen. An artist's book consisting of 100 sheets of transparent plastic bound to a white metal sheet. The only text is the title page. The rest of the book is totally blank.

Exhibitions

[edit]Manzoni's works were often featured at Galleria Azimuth.[18] His work has been the subject of numerous international exhibitions, including retrospectives at the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (1991), Castello di Rivoli-Museo d'Arte Contemporanea (1992), the Serpentine Gallery, London (1998), at the Museo d'Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina, Naples (2007), curated by Germano Celant, and in 2019 "Piero Manzoni: Materials of His Time" at Hauser & Wirth's Los Angeles and then New York City galleries.[19][20]

Collections

[edit]Manzoni's work is represented in many public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Tate Modern, London; the Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin;[19] and the Museum of Contemporary Art Villa Croce in Genoa.

Legacy

[edit]Fondazione Piero Manzoni, a family-run Italian foundation, oversees the artist’s estate. It has been represented by Hauser & Wirth since 2017.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Grove Art Online, Arte Povera,

- ^ a b Grove Art Online, Piero Manzoni, essay by Laural Weintraub,

- ^ Tate Online

- ^ Art Invest/Manzoni biography

- ^ a b c Silk, Gerald. Myths and Meanings in Manzoni's Merda d'artista, Art Journal, Vol. 52, No. 3, Autumn, 1993

- ^ Piero Manzoni, Catalog Raisoné, Battino & Palazzoli, p162

- ^ Manzoni, Celant, Electa, p22

- ^ Yves Klein, Sidra Stich, Hayward Gallery, p82

- ^ Piero Manzoni, Catalog Generale, First Vol, Celant

- ^ Piero Manzoni, Germano Celant, p 262

- ^ Scott Reyburn (October 7, 2014), Auction Houses Gear Up for Frieze Week New York Times.

- ^ Rauschenberg/ Art and Life, Kotz, Abrams p76

- ^ Manzoni, Celant, Electa 2007, p207

- ^ Poop Culture: How America is Shaped by its Grossest National Product by Dave Praeger ISBN 1-932595-21-X

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan (2007-06-13). "Merde d'artiste: not exactly what it says on the tin". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Catalogue item from Sotheby's 20th Century Italian Art sale, 20 October 2008

- ^ Artist's Multiples 1935-2000, Stephen Bury, Ashgate

- ^ Piero Manzoni Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

- ^ a b Piero Manzoni Gagosian Gallery.

- ^ "Exhibitions — Piero Manzoni Materials of His Time - Piero Manzoni | Hauser & Wirth".

- ^ Alex Greenberger (June 8, 2017), Foundation for Piero Manzoni Goes to Hauser & Wirth ARTnews.

Bibliography

[edit]- Piero Manzoni. Catalogo Generale, edited by G. Celant, Prearo Editore, Milan, 1975.

- Piero Manzoni. Catalogue raisonné, edited by F. Battino, L. Palazzoli, Edizioni di Vanni Scheiwiller, Milan, 1991.

- Piero Manzoni. General catalogue, edited by G. Celant, interview of G. Celant, Skira, Geneva-Milan, 2004.

- Piero Manzoni, edited by G. Celant, exhibition catalogue (MADRE Museo di Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina, Naple), Electa, Milan, 2007.

- Piero Manzoni: Azimut, exhibition catalogue (Gagosian Gallery, London), Gagosian Gallery, 2011.

- P. Manzoni, Diario, edited by G. L. Marcone, Mondadori Electa, Milan, 2013.

- F. Pola, Una visione internazionale. Piero Manzoni e Albisola, Mondadori Electa, Milan, 2013.

- G. Celant, Su Piero Manzoni, Abscondita, Milan, 2014. - F. Gualdoni, Breve storia della “Merda d’artista”, Skira, Geneva-Milan, 2014.

- E. Manzoni, Caro Piero, Skira, Geneva-Milan, 2014.

- F. Pola, Piero Manzoni and ZERO. A European Creative Region, Mondadori Electa, Milan, 2014.

- A. Bettinetti, Piero Manzoni, Artist, Cinehollywood, 2014 (DVD). - Piero Manzoni 1933-1963, edited by F. Gualdoni and R. Pasqualino di Marineo, exhibition catalogue, (Palazzo Reale, Milan), Skira, Geneva-Milan, 2014.

- G. Pautasso, Piero Manzoni. Divorare l’arte, Mondadori Electa, Milan, 2015.

- AZIMUT/H. Continuity and Newness, edited by L. Barbero, exhibition catalogue (Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice), Marsilio Editori, Venice, 2015.

- Piero Manzoni, Achrome, edited by C. Léveque-Claudet and C. Kazarian, exhibition catalogue (Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne, Lausanne), Editions Hazan, Lausanne, 2016.

- Piero Manzoni. Nuovi studi, edited by R. Pasqualino di Marineo, Carlo Cambi Editore, Poggibonsi, 2017.

- R. Perna, Piero Manzoni e Roma, Mondadori Electa, Milan, 2017.

- Piero Manzoni. Materials of His Time and Lines, edited by R. Pasqualino di Marineo, exhibition catalogue (Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles and New York), Hauser & Wirth Publishers, Zürich, 2019.

- F. Gualdoni, Piero Manzoni. An Artist's Life, Gagosian, New York, 2019.

- P. Manzoni, Piero Manzoni. Writings on Art, edited by G. L. Marcone, Hauser & Wirth Publishers, Zürich, 2019.

- Merda d’artista Künstlerscheisse Merde d’artiste Artist's Shit, Carlo Cambi Editore, Poggibonsi, 2021.