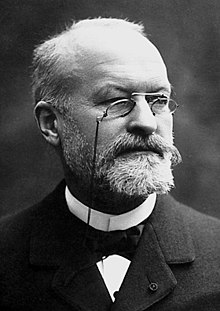

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 June 1845 Paris, France |

| Died | 18 May 1922 (aged 76) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Cimetière du Montparnasse 48°50′N 2°20′E / 48.84°N 2.33°E |

| Alma mater | University of Strasbourg |

| Known for | Trypanosomiasis, malaria |

| Spouse | Sophie Marie Pidancet |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1907) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Tropical medicine Parasitology |

| Institutions | School of Military Medicine of Val-de-Grâce Pasteur Institute |

| Signature | |

| |

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (18 June 1845 – 18 May 1922) was a French physician who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907 for his discoveries of parasitic protozoans as causative agents of infectious diseases such as malaria and trypanosomiasis. Following his father, Louis Théodore Laveran, he took up military medicine as his profession. He obtained his medical degree from University of Strasbourg in 1867.

At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, he joined the French Army. At the age of 29 he became Chair of Military Diseases and Epidemics at the École de Val-de-Grâce. At the end of his tenure in 1878 he worked in Algeria, where he made his major achievements. He discovered that the protozoan parasite Plasmodium was responsible for malaria, and that Trypanosoma caused trypanosomiasis or African sleeping sickness.[1] In 1894 he returned to France to serve in various military health services. In 1896 he joined Pasteur Institute as Chief of the Honorary Service, from where he received the Nobel Prize. He donated half of his Nobel prize money to establish the Laboratory of Tropical Medicine at the Pasteur Institute. In 1908, he founded the Société de Pathologie Exotique.[2]

Laveran was elected to French Academy of Sciences in 1893, and was conferred Commander of the National Order of the Legion of Honour in 1912.

Early life and education

[edit]Alphonse Laveran was born at Boulevard Saint-Michel in Paris, to parents Louis Théodore Laveran and Marie-Louise Anselme Guénard de la Tour Laveran.[3] He was an only son and had an older sister.[3] His family was in a military environment. His father was an army doctor and a professor of military medicine and epidemiology at the medical school, École de Val-de-Grâce in Paris. His mother was the daughter of an army commander.[4]

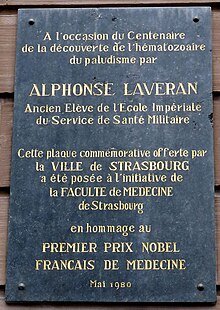

At a young age, his family moved to Metz in northeast France where his father became professor at the military hospital. At age five, the family moved to Blida in Algeria, North Africa.[1] 1856, he returned to Paris for education, and completed his higher education from Collège Sainte-Barbe and obtained the bachelor's degree inscience (baccalaureate) from the Lycée Louis-le-Grand.[4] Following his father he chose military medicine and entered the public health schools, simultaneously at École Impériale du Service de Santé Militaire (Saint Martin Military Hospital) in Paris and the Faculté de Médecine (Department of Medicine) of the University of Strasbourg in 1863.[3] In 1866, he became a resident medical student in the Strasbourg civil hospitals.[4] In 1867, he submitted a thesis titled Recherches expérimentals sur la régénération des nerfs (Research Experiments on the Regeneration of Nerves) by which he earned his medical degree from the University of Strasbourg.[5]

Career

[edit]Laveran was appointed Aide-major at the Saint Martin Military Hospital soon after his graduation. During the Franco-Prussian War, he served in the French Army as Medical Assistant-Major. After serving at the battles of Gravelotte and Saint-Privat, he was posted to Metz, where the French were eventually defeated and the place occupied by Germans.[4] He was briefly taken as prisoner-of-war, but as a physician, he was sent to work at Lille hospital where he remained till the end of the war in 1871.[1]

As a civil war immediately followed (the Paris Commune from 18 March to 28 May 1871), he was stationed at the Saint Martin Military Hospital. In 1874, he qualified a competitive examination by which he was appointed to the Chair of Military Diseases and Epidemics at the École de Val-de-Grâce, a position his father had occupied. His tenure ended in 1878 and he was sent to Algeria, where he remained until 1883.[4] Working at military hospitals in Bône (now Annaba) and Constantine, he began to have experience in the study of blood infection as malaria was prevalent.[6] However, he was transferred to Biskra where there were no malarial cases and he investigated a disease called Biskra button. He returned to Constantine in 1880.[4]

From 1884 to 1889, Laveran was Professor of Military Hygiene at the École de Val-de-Grâce. In 1894 he was appointed Chief Medical Officer of the military hospital at Lille and then Director of Health Services of the 11th Army Corps at Nantes. By then he was promoted to the rank of Principal Medical Officer of the First Class. In 1896, he entered the Pasteur Institute as Chief of the Honorary Service to pursue full-time research on tropical diseases.[7]

Achievements

[edit]

Malaria and discovery of malarial parasite

[edit]Laveran had first encounter with malarial parasites while working at Constantine. Malaria was till then considered as a miasmatic disease, a sort of mystical airborne infection.[8] From the blood samples of malarial individuals, Laveran observed pigmented cells (later known as haemozoin[9] which indicate infection of red blood cells with malarial parasite). He knew[10] that German physician Rudolf Virchow had described the malarial pigment in 1849.[11][12] Virchow had seen from a person who died of malaria several pigmented cells in the blood showed for the first time the link between blood infection and malaria.[13] However, he mistakenly identified the pigmented cells as those of endothelial cells from the spleen and white blood cells.[14] Malarial infection therefore erroneously known as pigmented white blood cells (melaniferous leucocytes).[15] Laveran was the first to think of such infected blood cells were by parasites, but his interest in the issue was ended by his transfer to non-malarial station.[4]

Soon after he returned to the military hospital in Constantine, Algeria, in 1880, Laveran discovered the cause of malaria as a protozoan, after observing the parasites in a blood smear taken from a person who had just died of malaria.[16] On 20 October, he first noticed the parasite in various forms and described it with, as later remarked, "accurate"[17] and "excellent freehand drawings."[6] His initial hunch that pigmented cells in malaria were due to parasitic infection became obvious as he observed not only pigmented cells, but also several cells with filaments that were moving about. He continued to investigate other cases of malaria and reported his discoveries on 24 December to the Société médicale des hôpitaux de Paris. He described three unique biological characters of malarial parasite: crescent or oval bodies that were transparent and had rounded pigment granules at the centre, spherical bodies that possessed three to four filaments capable of worm-like movements, and smaller spherical bodies that had small granules and lacked filaments.[18] The crescent or oval cells are now known as the gametocytes, filamented bodies as exflagellation (male gamete), and small spherical bodies as trophozoites.[19]

Laveran's report was published in 1881 in the Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société médicale des hôpitaux de Paris, and in English in The Lancet.[8][20] He wrote:

On the 20th October last, while examining by microscope the blood of a patient suffering from malarial fever I observed in the midst of the red blood corpuscles the presence of elements which appeared to me to be of parasitic origin. Since then I have examined 44 cases, and in 26 have found the same elements. I have searched in vain for these elements in the blood of patients suffering from diseases other than malaria.[18]

The same year he published a 104-paged monograph Nature parasitaire des accidents de l'impaludisme: description d’un nouveau parasite trouvé dans le sang des malades atteints de fièvre palustre (Parasitic Nature of Malarial Disease: Description of a New Parasite Found in the Blood of Patients with Malarial Fever).[21] In it, he named the parasite Oscillaria malariae[22] (which after a long line of research and nomenclature controversies the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature officially renamed Plasmodium falciparum in 1954[23]). This was the first time that protozoans were shown to be a cause of disease of any kind. The discovery was therefore a validation of the germ theory of diseases.[24]

However, Laveran's announcement was received with skepticism mainly because by that time leading physicians such as Theodor Albrecht Edwin Klebs and Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli claimed that they had discovered a bacterium (which they called Bacillus malariae) as the pathogen of malaria. Laveran's discovery was widely accepted only after five years when Camillo Golgi confirmed the parasite using better microscope and staining technique.[8]

Laveran was a supporter of the mosquito-malaria theory[4] developed by British physician Patrick Manson in 1894, and experimentally proved by Ronald Ross in 1898.[8] Based on this medical development, he reported malaria condition of Corsica in 1901 urging the need for eradication and control of mosquitos. The French Academy of Medicine established Ligue corse contre le Paludisme (The League of Corsica to Combat Malaria) with Laveran as its honorary president in 1902.[25]

Leishmaniasis

[edit]

Laveran came across another protozoan disease, cutaneous leishmaniasis, caused by different species of Leishmania, at Biskra, where it was known as clou de Briska (Biskra button) because of the obvious button-like skin sores in infected individuals.[26] Although he failed to make valuable observations, he was the first to identify the causative protozoan of a similar disease, now called visceral leishmaniasis. In 1903, while at the Pasteur Institute, he received the specimens from a British medical officer Charles Donovan from Madras, India, and with the help of his colleague Félix Mesnil, he named it Piroplasma donovanii.[27][28] However, the scientific name was corrected to Leishmania donovani the same year.[29][30] In 1904, he and M. Cathoire reported the first case of infantile leishmaniasis from Tunisia.[31] He published a treatise on leishmaniasis in 1917.[6]

Trypanosomiasis

[edit]Laveran later worked on the trypanosomes and showed once again that the protozoans were responsible for the disease such as sleeping sickness and animal trypanosomiasis.[32] He described Trypanosoma theileri from cattle in 1902;[33] Trypanosoma nanum in 1905 and Trypanosoma Montgomeryi in 1909, which were later corrected as Trypanosoma congolense, a parasite of nagana in cattle and horses.[34] With Mesnil, he identified Trypanosoma granulosum from European eels in 1902;[35] Trypanoplasma borelli[36] and Trypanosoma raiae from fish in 1902; Trypanosoma danilewskyi from fish in 1904;[36] and published a monograph Trypanosomes and Trypanosomiases (Trypanosomes et Trypanosomiases) in 1904[37] by which more than thirty new species were described.[4]

Awards and honours

[edit]Laveran was awarded the Bréant Prize (Prix Bréant) of the French Academy of Sciences in 1889 and the Edward Jenner Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1902 for his discovery of the malarial parasite.[38] He received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907 "in recognition of his work on the role played by protozoa in causing diseases."[39] He gave half the Prize for foundation of the Laboratory of Tropical Medicine at the Pasteur Institute.[38] He was honorary fellow of the Royal Society, Royal Society of Edinburgh, Royal Society of Medicine, Pathological Society, Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, and Royal Society for Public Health.[4]

In 1908, he founded the Société de pathologie exotique, over which he presided for 12 years. He was elected to membership in the French Academy of Sciences in 1893, and became its President 1920. He was conferred Commander of the National Order of the Legion of Honour in 1912. He was Honorary Director of the Pasteur Institute in 1915 on his 70th birthday. His work was commemorated philatelically on a stamp issued by Algeria in 1954.[38]

Personal life and death

[edit]

Laveran married Sophie Marie Pidancet in 1885. They had no children.[3]

In 1922 he suffered from an unspecified illness for some months and died in Paris.[40][41] He is interred in the Cimetière du Montparnasse in Paris. He was an atheist.[42]

Recognition

[edit]Laveran's name features on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Twenty-three names of public health and tropical medicine pioneers were chosen to feature on the School building in Keppel Street when it was constructed in 1926.[43]

Works

[edit]Laveran was a solitary but dedicated researcher and he wrote more than 600 scientific communications. Some of his major books are:[44][45]

- Nature parasitaire des accidents de l'impaludisme, description d'un nouveau parasite trouvé dans le sang des malades atteints de fièvre palustre. Paris 1881

- Traité des fièvres palustres avec la description des microbes du paludisme. Paris 1884

- Traité des maladies et épidémies des armées. Paris 1875

- Trypanosomes et Trypanosomiases . Masson, Paris 1904 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Nye, Edwin R (2002). "Alphonse Laveran (1845–1922): discoverer of the malarial parasite and Nobel laureate, 1907". Journal of Medical Biography. 10 (2): 81–7. doi:10.1177/096777200201000205. PMID 11956550. S2CID 39278614.

- ^ Garnham, PC (1967). "Presidential address: reflections on Laveran, Marchiafava, Golgi, Koch and Danilewsky after sixty years". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 61 (6): 753–64. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(67)90030-2. PMID 4865951.

- ^ a b c d Oakes, Elizabeth H. (2007). Encyclopedia of World Scientists (Revised ed.). New York (US): Facts on File. pp. 427–428. ISBN 978-1-43-811882-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sequeira, JH (1930). "Alphonse Laveran and his work". British Medical Journal. 1 (3624): 1145–1147. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3624.1145. JSTOR 25336486. PMC 2313558. PMID 20775532.

- ^ Laveran, Alphonse (1867). Recherches expérimentales sur la régénération des nerfs (in French). Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de santé (Paris).

- ^ a b c "Professor Laveran". The British Medical Journal. 1 (3207): 979. 1922. ISSN 0007-1447. JSTOR 20420334.

- ^ "Alphonse Laveran – Biographical". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d Lalchhandama, K (2014). "The making of modern malariology: from miasma to mosquito-malaria theory" (PDF). Science Vision. 14 (1): 3–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2014.

- ^ "Etymologia: Hemozoin". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (2): 343. 2016. doi:10.3201/eid2202.ET2202. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 4734516.

- ^ Manson-Bahr, P. (1961). "The malaria story". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 54 (2): 91–100. doi:10.1177/003591576105400202. PMC 1870294. PMID 13766295.

- ^ Sullivan, David J (2002). "Theories on malarial pigment formation and quinoline action". International Journal for Parasitology. 32 (13): 1645–1653. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00193-5. PMID 12435449.

- ^ Hempelmann, Ernst (1 March 2007). "Hemozoin Biocrystallization in Plasmodium falciparum and the antimalarial activity of crystallization inhibitors". Parasitology Research. 100 (4): 671–676. doi:10.1007/s00436-006-0313-x. ISSN 1432-1955. PMID 17111179. S2CID 30446678.

- ^ Kapishnikov, Sergey; Hempelmann, Ernst; Elbaum, Michael; Als-Nielsen, Jens; Leiserowitz, Leslie (18 May 2021). "Malaria Pigment Crystals: The Achilles′ Heel of the Malaria Parasite". ChemMedChem. 16 (10): 1515–1532. doi:10.1002/cmdc.202000895. ISSN 1860-7179. PMC 8252759. PMID 33523575.

- ^ Welch WH, Thayer WS (1897). "Malaria". In Loomis, AE, Thompson WG (eds.). A System of Practical Medicine By American Authors. New York: Lea Brothers & Co. pp. 19–20. OCLC 6836952.

- ^ Thayer, William Sydney; Hewetson, John (1895). The Malarial Fevers of Baltimore: An Analysis of 616 Cases of Malarial Fever, with Special Reference to the Relations Existing Between Different Types of Haematozoa and Different Types of Fever. Johns Hopkins Press. p. 8.

- ^ Bruce-Chwatt LJ (1981). "Alphonse Laveran's discovery 100 years ago and today's global fight against malaria". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 74 (7): 531–536. doi:10.1177/014107688107400715. PMC 1439072. PMID 7021827.

- ^ Thayer, William Sydney; Hewetson, John (1895). Ibid. p. 6.

- ^ a b Thayer, William Sydney; Hewetson, John (1895). Ibid. pp. 7–8.

- ^ Tuteja, Renu (2007). "Malaria − an overview". FEBS Journal. 274 (18): 4670–4679. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05997.x. PMID 17824953. S2CID 32648254.

- ^ Laveran, A (1881). "The pathology of malaria". The Lancet. 2 (118) (3037): 840–841. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)35653-8.

- ^ Laveran, Alphonse (1881). Nature parasitaire des accidents de l'impaludisme: description d'un nouveau parasite trouvé dans le sang des malades atteints de fièvre palustre (in French). Paris: Baillière. OCLC 14864248.

- ^ Cox, Francis EG (2010). "History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors". Parasites & Vectors. 3 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-5. PMC 2825508. PMID 20205846.

- ^ Bruce-Chwatt, L.J. (1987). "Falciparum nomenclature". Parasitology Today. 3 (8): 252. doi:10.1016/0169-4758(87)90153-0. PMID 15462972.

- ^ Sherman, Irwin (2008). Reflections on a Century of Malaria Biochemistry. Vol. 67. London: Academic Press. pp. 3–4. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(08)00401-6. ISBN 978-0-0809-2183-9. PMID 18940418.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Jaujou, C. M. J. (1954). "La lutte antipaludique en Corse". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 11 (4–5): 635–677. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 2542265. PMID 13209316.

- ^ Steverding, Dietmar (15 February 2017). "The history of leishmaniasis". Parasites & Vectors. 10 (1): 82. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2028-5. ISSN 1756-3305. PMC 5312593. PMID 28202044.

- ^ A, Laveran (1903). "Sur un protzaire nouveau (Piroplasma donovani Lav. et Mesn.). Parasite d'une fievre de l'Inde". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences. 137: 957–961.

- ^ Gibson, Mary. E. (1983). "The identification of kala-azar and the discovery of Leishmania Donovani". Medical History. 27 (2): 203–213. doi:10.1017/S0025727300042691. ISSN 0025-7273. PMC 1139308. PMID 6345968.

- ^ Ross, R. (1903). "Further notes on Leishman's bodies". British Medical Journal. 2 (2239): 1401. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2239.1401. PMC 2514909. PMID 20761210.

- ^ Dutta, Achinya Kumar (2009). "Medical research and control of disease: Kala-azar in British India". In Pati, Biswamoy; Harrison, Mark (eds.). The Social History of Health and Medicine in Colonial India (Reprinted. ed.). London: Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 9780203886984.

- ^ Haouas, N.; Gorcii, M.; Chargui, N.; Aoun, K.; Bouratbine, A.; Messaadi Akrout, F.; Masmoudi, A.; Zili, J.; Ben Said, M.; Pratlong, F.; Dedet, J.P. (2007). "Leishmaniasis in central and southern Tunisia: current geographical distribution of zymodemes". Parasite. 14 (3): 239–246. doi:10.1051/parasite/2007143239. ISSN 1252-607X. PMID 17933302.

- ^ Sundberg, C (2007). "Alphonse Laveran: the Nobel Prize for Medicine 1907". Parassitologia. 49 (4): 257–60. PMID 18689237.

- ^ Lamy, Louis; Bouley, Georges (1967). "Observation en France, chez un Veau, d'un cas d'infection massive à Trypanosoma theileri, Laveran 1902 (Note présentée par M. VA LLEE )". Bulletin de l'Académie Vétérinaire de France. 120 (7): 323–325. doi:10.4267/2042/66711.

- ^ Stephen, L. E. (1963). "On the Validity of Trypanosoma Montgomeryi Laveran , 1909". Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology. 57 (4): 397–403. doi:10.1080/00034983.1963.11686191. ISSN 0003-4983. PMID 14101927.

- ^ Davies, A. J.; Mastri, C.; Thorborn, D. E.; Mackintosh, D. (1995). "Experiments with growth of the eel trypanosome, Trypanosoma granulosum Laveran & Mesnil, 1902, in semi-defined and defined media". Journal of Fish Diseases. 18 (6): 599–608. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2761.1995.tb00364.x. ISSN 0140-7775.

- ^ a b Dykova, Iva; Lom, J. (1979). "Histopathological changes in Trypanosoma danilewskyi Laveran & Mesnil, 1904 and Trypanoplasma borelli Laveran & Mesnil, 1902 infections of goldfish, Carassiw auratus (L.)". Journal of Fish Diseases. 2 (5): 381–390. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2761.1979.tb00390.x. ISSN 0140-7775.

- ^ Laveran, Alphonse; Mesnil, Félix (1904). Trypanosomes et Trypanosomiases: avec 61 Fig. et 1 Planche (in French). Paris: Masson.

- ^ a b c Haas, L F (1999). "Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (1845-1922)". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 67 (4): 520. doi:10.1136/jnnp.67.4.520. PMC 1736558. PMID 10486402.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1907". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ Nobel Lectures, Physiology or Medicine 1901-1921. Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing Company. 1967. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Alphonse Laveran - Facts". Nobel Media AB. 2014.

- ^ Smith, Warren Allen (1 January 2000). Who's who in Hell: A Handbook and International Directory for Humanists, Freethinkers, Naturalists, Rationalists, and Non-theists. Barricade Books. p. 648. ISBN 9781569801581. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Behind the Frieze". LSHTM. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ "Laveran, Alphonse, 1849-1922 [books by]". Internet Archive. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Online Books by Alphonse Laveran". onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

Further reading

[edit]External links

[edit]- Alphonse Laveran on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture on 11 December 1907 Protozoa as Causes of Diseases

- CDC profile

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- Faqs.org profile

- Encyclopedia of World Biography

- Timeline of Laveran at Pasteur Institute

- 1845 births

- 1922 deaths

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- French atheists

- French Nobel laureates

- French tropical physicians

- Malariologists

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Foreign Members of the Royal Society

- Burials at Montparnasse Cemetery

- University of Strasbourg alumni

- French parasitologists

- Pasteur Institute

- French Army officers

- French military doctors

- Recipients of the Cothenius Medal

- Recipients of the Jenner Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine