Volodymyr Pravyk

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Ukrainian. (March 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Volodymyr Pravyk | |

|---|---|

| Native name | Володимир Павлович Правик |

| Birth name | Volodymyr Pavlovych Pravyk |

| Born | 13 June 1962 Chernobyl, Ukraine SSR, USSR |

| Died | 11 May 1986 (aged 23) Moscow, Russian SFSR, USSR |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Paramilitary Fire Service, Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR |

| Years of service | 1979–1986 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | Third Watch, Paramilitary Fire Station No. 2 (Chernobyl NPP Fire Station) |

| Awards | Hero of the Soviet Union, Order of Lenin, Order For Courage |

| Spouse(s) | Nadia Pravyk |

| Children | Natasha Vladimirovna Pravyk |

| Relations | Pavel Opanasovich Pravyk (Father) Natalia Ivanova Pravyk (Mother) Vitya Pavelovich Pravyk (Brother) |

Volodymyr Pavlovych Pravyk (Ukrainian: Володимир Павлович Правик, Russian: Владимир Павлович Правик, romanized: Vladimir Pravik; 13 June 1962 – 11 May 1986) was a Soviet firefighter notable for his role in directing initial efforts to extinguish fires following the Chernobyl Disaster. Following the event, he was hospitalized with acute radiation syndrome and died sixteen days later. He was posthumously awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union and the Order of Lenin by the Soviet Union, and later the Ukrainian Star For Courage (later known as the Order for Courage) in recognition of his efforts.

Early life

[edit]

Volodymyr Pravyk was born in the town of Chernobyl on 13 June, 1962. His mother, Natalia Ivanivna Pravyk, was a nurse, and his father, Pavlo Opanasovych Pravyk, a construction worker.[1] Both were local Poleshuks who had lived in Chernobyl all their lives.[1] Pravyk's younger brother and only sibling, Viktor Pavlovych Pravyk, was born eight years later.[1] In his childhood, Pravyk enjoyed reading and was academically inclined. He developed interests in photography, electronics repair, and mathematics.[1] His mother expected that he would seek admission to a university to study the latter.[1] However, with support from a neighbor who served in the fire service, Pravyk elected to enroll in the Cherkasy Fire-Technical Academy at the end of his primary schooling in 1979, and to become a firefighter.[1]

Firefighting career

[edit]Pravyk completed a three year term of study and training at the Cherkasy Fire-Technical Institute between 1979 and 1982, and graduated as a junior officer in the Paramilitary Fire Service of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR (MVD).[2] Following this, Pravyk returned to Chernobyl and took up a junior command position in Paramilitary Fire Brigade No.2 (СВПЧ-2) of the Kiev Executive Committee, based at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant.[1][3]

Commander of the Third Watch

[edit]By 1986, Pravyk was the commander of the fire brigade's third watch, and a lieutenant in the MVD.[4][5]

The fourteen-man watch he commanded was not known for a high degree of discipline.[5] In the words of Major Leonid Telyatnikov, the commander of the fire brigade: "It was a highly distinctive unit. You could say that it was a unit of individuals,... everyone was on his own. There were a great many veterans there, a great many mavericks."[3] According to historian Serhii Plokhy, the men of the third watch sometimes "took advantage of [Pravyk] and occasionally let him down".[3] The local men who filled the ranks were often related or from the same villages, and their longstanding relationships were hard for his authority to penetrate.[5][3] Nevertheless, Pravyk led by example, and was attentive to the needs and desires of his subordinates.[3] He brought their concerns and requests for time off and improved living conditions directly to Telyatnikov.[6] He once publicly opposed his commander over what punishment a subordinate of his was to receive for confusing dates and missing his shift, calling for leniency in addressing the misunderstanding.[6] The firefighters of his shift held him in high regard. Leonid Shavrey, a firefighter and squad leader in the Third Watch, is quoted as saying:

Pravyk was a very good guy. Brainy and competent. He was very knowledgeble about radio engineering, which he loved very much. He was something of a master with light shows or repairing receivers and tape recorders. And he got along well with the men. A fine commander. He could settle any question: if you approached him, he would see to it promptly.[7]

In his time with the brigade, Pravyk helped to design and install a remote-control door-opening mechanism for the fire station's garage- which was a rare feature in the Soviet Union at the time.[1][3] At the time of the accident, he was planning to continue his education and further his firefighting career by attending a Higher Fire-Engineering School, which would qualify him for a position as a senior officer.[8]

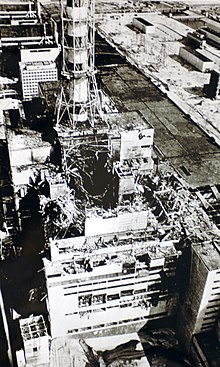

Chernobyl disaster

[edit]

Lieutenant Pravik's third shift was on duty at the time of the disaster. When the reactor exploded at 01:23 in the morning, Pravik was in his office writing - presumably a letter to his wife, which he would frequently do in his shifts away from home.[9]

A group of Pravik's men were outside of the fire station standing on the apron, on a smoke break. Senior fireman Ivan Shavrey remembers hearing the initial steam explosion from the direction of the power plant, and brushed it off, as he likened it to a steam release, the likes of which they had heard many times before, and was a common occurrence. A few seconds later, the much larger hydrogen explosion ripped through the roof of the fourth power unit, right in front of their eyes. [10] Within an instant, the men on shift, Pravik among them, scrambled to the fire station doors to see what had happened. They immediately sprang into action and began donning their protective gear as fast as possible. Pravik ran back into his office, presumably to grab a radio. [11]

At approximately 01:25, around a minute after the explosion, firefighting vehicles were already leaving the station.[12] Sergeant Anatoly Zakharov was leading the column in an ANR40 (130) 127A,[10] Lieutenant Pravik's car, driven by sergeant Andrey Korol, an AC40 (130) 63B, followed closely behind. Lastly in the column was senior sergeant Ivan Butrimenko, who was driving a foam extinguishing vehicle (AKT (133Gya) 2.5/31-197).[13] The vehicles turned left out of the fire station and passed through the first administration building (ABK-1), then passing BT-2, and the 'Romashka' canteen, finally coming to a stop between the transport corridors of units 3 & 4. [3] [5]

When seeing the destroyed remains of unit four through his vehicles' windshield, Pravik calls for a stage 3 alarm, which summons all available fire departments in the Kiev Oblast to the signal.[3][4][5]

The firefighters immediately disembark the vehicles. Lieutenant Pravik and another firefighter; Leonid Shavrey (Ivan's brother) set out on reconnaissance, to try and determine the source of the fire, and to figure out what had happened.[14] They disappear into the unit three transport corridor, then over into unit four's. Pravik runs into a distressed plant worker who is fleeing from the block, Pravik asked the man what had happened, and where the fire was, the worker responded that there was a fire in the turbine hall.[3][14] Pravik then attempts to phone unit four's control room - the line was down. [3]

Pravik sends Leonid Shavrey back out to the trucks and orders them to be turned around and repositioned at the southern wall of the turbine hall, in order to tackle the fires there.[13] Pravik himself continues his reconnaissance mission further into the plant; heading for the turbine hall. He reaches the turbine hall at around 01:32 and asks turbinists Busygin and Korneev what the situation in the turbine hall is.[15] Pravik sees the concaved roof and the piles of debris, but is told that the staff have the fires inside under control, they suggest he focuses his efforts on the roof of the turbine hall. Pravik leaves the turbine hall at 01:35.[15]

At around the same time (01:35), Lieutenant Viktor Kibenok arrives with 9 firefighters from Pripyat.[3][5][14] Initially arriving on the southern side of the plant, along the turbine hall. Kibenok raises Pravik over the radio. Pravik tells him that his men have the turbine hall roof fires under control, and requests that Kibenok moves his vehicles to the northern side of the reactor building, in order to tackle the fires that had begun on the roof of the ventilation block, and to protect reactor three which was still operational.[13]

By 01:40, Kibenok's three vehicles (AC40 (130) 63B, AC40 (375) C1A and AL30 (131) L21) had been moved to the north side of the reactor building ("Row B").[13] The mechanical ladder truck had been deployed under the auxiliary reactor system block (VSRO) giving firefighters access to mark +21.5, the roof of the VSRO building. Pravik sends Lieutenant Kibenok to the roof of the VSRO block on reconnaissance, and to extinguish the small fires starting there. Kibenok takes two firefighters and two hose lines and climbs up the mechanical ladder. [13][16]

At 01:47, Major Leonid Telyatnikov arrives on scene along 'Row A' (turbine hall), and officially takes scene command from Lieutenant Pravik, who up until this point, was the de-facto site commander.[10] [14]At around the same time, reinforcements from the town of Chernobyl arrive on the north side of the reactor building. Their commander, Grigory Khmel, speaks with Pravik; Pravik orders Khmel to move his trucks closer to the reactor building, and to start connecting his trucks to the cisterns and dry pipes running up the side of the reactor block.[16]

At around 01:51, Pravik takes a small team of four other firefighters (V. Ignatenko, V. Tishura, N. Vashchuk, N. Titenok) and begins his seventy-meter climb to the roof of block three. Using the fire escape staircase on the northern face of the block, they reach the roof of reactor three at around 01:56.[13][12] Since there are no fires on the reactor roof itself, they climb to the roof of the ventilation block at mark +75.5 and begin extinguishing fires there.[3]

At 02:01, Pravik reports over the radio: "Explosion in the reactor compartment of unit four".[12] This is heard by all radios all over the site. Kibenok, who is still on the roof at mark +21.5, decides to climb to the roof of the ventilation block, possibly out of curiosity, which would ultimately lead to his death. Four minutes later, Major Telyatnikov makes the decision to call up the second shift of firemen from the nuclear plant's fire station.[12] Pravik's report of an explosion in the reactor hall catches the attention of the central fire dispatcher in Kiev, who fifteen minutes later, decides the Ukrainian KGB should be called as the fire involved the reactor. [12]

The firefighting on the roof of the ventilation block was made difficult by the fact that the dry pipes running up the height of the reactor building were shattered by the force of the explosion. This required hoses to be laid manually, seventy meters high, to the roof of the reactor building. The bitumen covering on the roof had also begun to melt, making the working environment extremely hot, and the melted asphalt stuck to their boots, making it hard to move around. The water pressure from the hoses wasn't high enough, as the hose length had been stretched to its limits leading the fire hoses they had to be largely ineffective. Instead, the firemen reportedly stomped on the burning pieces of fuel in an attempt to extinguish them. [2][13][16]

By 02:14, Vladimir Tishura had collapsed,[13] weakened by the early symptoms of acute radiation sickness after working in fields of up to 6,000+ roentgens per hour, shortly followed by Nikolai Titenok. At 02:15, Lieutenant Pravik made the decision to descend from the roof, he reported this over radio. Three firefighters were sent to replace them. The weakened firemen assisted each other down the staircase, namely Vasily Ignatenko, who carried Tishura and Titenok down across the VSRO roof. [10][16]

Once on the ground, the six firefighters are helped out of their uniforms by their comrades. Pravik passes by Telyatnikov. Telyatnikov remembers: "Pravik descended. He looked terrible, with a round, red face, round bulging eyes. Wheezing. He went to the ambulance."[17]

The six firefighters get into two fire engines and are driven the short distance to ABK-2, the second administration building where they meet ambulance doctors, chief among them; Dr. Valentyn Belokon whom speaks with Viktor Kibenok. Belokon asks Kibenok if there are any burns cases, Kibenok says no, but that the situation is still unclear, and that something has got his men feeling nauseous. At this time, Pravik jumps out of the truck, however he does not walk up to Belokon. The doctor administers relanium and chlorpromazine to ease their pain. [16]

At 02:35, the six firefighters are taken to the Pripyat Hospital. [3][13]

Hospitalization and death

[edit]As the extent of the radioactive contamination released by the accident and the severity of their radiological injuries became clear, Pravyk and the other hospitalized firefighters and plant staff were evacuated by road to Borispol Airport in Kiev in the afternoon of April 26th, and then from there to Moscow by air overnight.[18]

There he and the others were transported to Hospital No. 6, a hospital operated by Sredmash (the Soviet state nuclear energy agency) and the All-Union Physics Institute, which had a specialized radiological department for treating workers injured in radiation incidents.[19]

During his hospitalization, Pravyk was attended regularly by his mother, who came from Moscow and remained there until his death.[20] After the initial symptoms of his radiation exposure passed, Pravyk was optimistic, and hoped that he would recover and see his family again, writing a cheerful letter from his bed to his wife:

- Nadya, you're reading this letter and crying. Don't dry your eyes. Everything turned out okay. We will live until we're a hundred. And our beloved little daughter will outgrow us three times over. I miss you both very much... Mama is here with me now. She hotfooted it over here. She will call you and let you know how I'm feeling. And I'm feeling fine.[1][20]

However, as time passed, the more severe damage to Pravyk's body began to manifest. Radiation damage to his bone marrow had lowered his white blood cell count, leaving him extremely vulnerable to infection, and damage to other cells in his body put his respiratory and digestive systems at risk of failure.[21] A bone marrow transplant, which would introduce healthy white blood cells from a viable donor into an afflicted patient, was the only treatment for such injuries at the time.[21] However, Pravyk, according to his mother, had lost so many white blood cells that the doctors determined a transplant would not be a viable solution, and informed his younger brother Vitya, who had stepped up to volunteer as a bone marrow donor for his older brother, that he could not be of any help.[1]

Pravyk succumbed to his injuries, with his mother at his side, around one in the morning on May 11, 1986.[1] He was interred with full military honors at Mitinskoe Cemetery in Moscow on May 13, 1986. Pravyk, like other initial victims of the Chernobyl Disaster, was buried in a coffin enclosed in a zinc box with both his body and coffin enclosed in plastic.[22][23]

According to a 2008 report by UNSCEAR, Vladimir Pravik received the highest confirmed dose at Chernobyl. His dose was estimated to be 1370 REM,[24] which is nearly triple that which would be considered a lethal dose. His cause of death was deemed ultimately to be complete respiratory failure.[25]

Personal life

[edit]

Volodymyr Pravyk was born near his place of employment, in the town of Chernobyl, and his parents lived there until the time of the disaster.[3] His hobbies included creative endeavors such as photography, drawing, and poetry.[5] He was also known for his aptitude with electrical engineering and repair.[7] He was a member of the Komsomol, the youth division of the Communist Party.[5]

Volodymyr Pravyk was married to Nadia Pravyk, whom he had met while he was attending the fire-technical school in Cherkasy and she was studying music in the city. They were married in 1984, and Nadia moved to Pripyat in 1985.[26] Prior to the Chernobyl disaster, she was employed as a music teacher at a kindergarten in Pripyat.[5] Volodymyr and Nadia Pravyk had one daughter named Natasha, who was born in Pripyat two weeks before the disaster at Chernobyl.[3][5] When the disaster occurred, his parents came to visit him at the Pripyat hospital prior to his evacuation to Moscow.[1] Through the window, Pravyk told them to see that his wife and daughter were evacuated safely to her parents' home in Central Ukraine, and that until that time they should stay indoors with the windows closed.[27] When Pripyat was evacuated the next day, Nadia and Natasha Pravyk would travel to Horodyshche, the city where her parents lived.[1]

Legacy

[edit]

Pravyk has been given posthumous honors by both the Soviet Union and Ukraine. On September 25, 1986, by a decision of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, he was posthumously awarded both the Order of Lenin and the title Hero of the Soviet Union.[2] In 1996, by a presidential order of Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma, he was posthumously given the Ukrainian Star for Courage for "exceptional personal courage and dedication, high professionalism, shown during the liquidation of the Chernobyl accident".[28]

Pravyk has also been honored with monuments and the dedication of landmarks in his memory. Busts in the Ukrainian city of Irpin, the "Alley of Chernobyl Heroes" in Kyiv, and at the fire-technical school in Cherkasy have been erected.[2] The Cherkasy fire technical school itself was rededicated in honor of both Pravyk and Kibenok, who also graduated from the institution.[29] A street is named after him in Cherkasy as well.[2] Pravyk's name is inscribed on several memorials to Chernobyl victims, including those in Kyiv and Simferopol.[2]

The Dogs of Chernobyl program, organized by the Clean Futures Fund and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, named a stray dog from the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone to honor Pravyk. The dog currently resides with his owner, the program's co-founder, in St. Louis, Missouri.[22]

Awards

[edit]See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Tkachuk 2011

- ^ a b c d e f "Правик Владимир Павлович". warheroes.ru. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Plokhy 2018, p. 94

- ^ a b "Pravyk Volodymyr Pavlovich". Book of Memory: Participants in the Liquidation of the Chernobyl Accident. National Chornobyl Museum. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Higgenbotham 2019, p. 58

- ^ a b Plokhy 2018, pp. 89–90

- ^ a b Plokhy 2018, p. 90

- ^ Plokhy 2018, p. 88

- ^ Plokhy, Serhii (2019). Chernobyl: History of a Tragedy. United Kingdom: Penguin (published 31 January 2019). pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0141988351.

- ^ a b c d 1987 Interview with Chernobyl Firefighters, from "The Bell of Chernobyl" film.[full citation needed]

- ^ Fireman Andrey Polovinkin's recollection (1996)[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d e Kyiv Central Fire Department Dispatch logs. Publicly available.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shkliar, Vasil (1988). Вогонь Чорнобиль [Fire of Chernobyl] (in Ukrainian). Kyiv: Unknown. p. 45.

- ^ a b c d Leatherbarrow, Andrew (16 April 2016). Chernobyl 01:23:40: The Incredible True Story of the World's Worst Nuclear Disaster (1st ed.). United Kingdom: Andrew Leatherbarrow. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0993597503.[self-published source?]

- ^ a b From German Busygin's official testimony.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d e Shcherbak, Iurii (1 June 1989). Chernobyl: A Documentary Story (in Ukrainian). Palgrave Macmillan (published 1989). pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-0312030971.

- ^ 1987 Interview with Leonid Telyatnikov. Available on YouTube.[full citation needed]

- ^ Higgenbotham 2019, p. 151

- ^ Higgenbotham 2019, p. 220

- ^ a b Higgenbotham 2019, p. 227

- ^ a b Higgenbotham 2019, p. 225

- ^ a b Higgenbotham 2019, p. 238

- ^ Plokhy 2018, p. 228

- ^ Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (Report). Vol. Annex D: Health effects due to radiation from the Chernobyl accident. United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. 2008. pp. 107–110. ISBN 978-92-1-054482-5. Archived from the original on 4 August 2024. Retrieved 3 August 2024 – via UNSCEAR.

- ^ Clinic of the Institute of Biophysics, Moscow (Angelina Guskova)

- ^ Plokhy 2018, pp. 88–89

- ^ Plokhy 2018, p. 100

- ^ Kuchma, Leonid. Про нагородження відзнакою Президента України - зіркою "За мужність" [About awarding with the award of the President of Ukraine - a star "For courage"]. Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ Історія становлення [History of the institute]. chipb-dsns-gov-ua. SES of Ukraine. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

Sources cited

[edit]- Higgenbotham, Adam (2019). Midnight in Chernobyl: The Untold Story of the World's Greatest Nuclear Disaster. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781501134647.

- "History of the institute". chipb-dsns-gov-ua. SES of Ukraine.

- Karplan, Nikolai (2012). From Chernobyl to Fukushima. Kyiv: S. Podgornov. ISBN 978-966-7853-00-6.

- Kuchma, Leonid. "About awarding with the award of the President of Ukraine - a star "For courage"". zakon.rada.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.

- Plokhy, Serhii (2018). Chernobyl: The History of the Nuclear Catastrophe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9781541617070.

- "Pravyk, Volodymyr Pavlovich". Book of Memory: Participants in the Liquidation of the Chernobyl Accident. National Chornobyl Museum.

- Tkachuk, Marina (27 April 2011). «Син до кінця вірив, що житиме...» [My Son Believed to the End That he Would Live]. Ukraina Moloda (in Ukrainian). No. 70. Retrieved 24 August 2021.