Environmental issues in Kenya

Environmental issues in Kenya include deforestation, soil erosion, desertification, water shortage and degraded water quality, flooding, poaching, and domestic and industrial pollution.[1]

Water resources

[edit]Water resources in Kenya are under pressure from agricultural chemicals and urban and industrial wastes, as well as from use for hydroelectric power.[2] The anticipated water shortage is a potential problem for the future. For example, the damming of the Omo river by the Gilgel Gibe III Dam together with the plan to use 30% to 50% of the water for sugar plantations will create significant environmental problems. Up to 50% of Lake Turkana's water capacity will be lost. Had there been no planning of the irrigation of sugar plantations, the dam itself might have had a net positive effect to the environment, due to the emission-less power generation of the dam.[3]

Water-quality in Kenya has problems in lakes, (including water hyacinth infestation in Lake Victoria), have contributed to a substantial decline in fishing output and endangered fish species.[4][5]

Animal poaching

[edit]

There are a wide variety of wildlife species in Kenya, whose habitats are threatened by encroachment of human development and destruction. In rural Kenya, poachers are one of the main threats to endangered animals. Michael Werikhe aka Rhino Man, made huge contributions to early Kenyan wildlife conservation. Werikhe walked thousands of kilometres and raised millions of dollars to fund White Rhino conservation projects. The Blue Wildebeest is currently abundant, but like other more endangered species feels the pressure of habitat reduction. Wildlife facing threats to poaching and trophy hunting include lions, elephants, gazelles, and rhinos. In February 2020, poachers in Kenya killed two white giraffes.[6] The female white giraffe and her calf were found dead in Garissa County, in the North-East part of the country.[7] There now remains only one male, white giraffe left in the world. Other critically endangered species in Kenya include the Tana River Mangabey, Black Rhino, Hirola, Sable Antelope, and Roan Antelope.[8]

Laws, regulation, and deterrence

[edit]During Kenya's colonial era (1895–1963), elephant and rhino hunting was viewed as an elite sport by British colonizers.[9] Post-independent Kenya saw a decrease in over half of the elephant population during the period of 1970 to 1977,[10] even though the country banned elephant hunting in 1973. In 1977, all animal hunting was banned in Kenya. The Kenya Wildlife Service was then established in 1989. The state corporation responded to high levels of poaching, insecurity in the conservation and wildlife parks, and inefficiency and low morale within Kenya's game department.[11] The international ban on the trade in ivory was implemented through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).[11] This law contributed to a significant but temporary decline in elephant poaching, which facilitated population rehabilitation.[11] Wildlife poaching and trafficking re-emerged in the 2000s due to increased demands of ivory and rhino horns, posing threats to extinction in the near future. The Kenyan Wildlife service works closely with Kenyan law enforcement agencies. However, some argue that conservation efforts should not be solved by what is called green militarization,[12] wherein conservation efforts and policies are aided by increased policing and criminalization. On the other hand, there may be circumstances in which militarization is a necessary measure.[13] In any case, scholars and policy-makers are interested in considering the effects of green washing policies in conservation and militarization.[13]

Ivory burning is a public event meant to deter animal poaching. Kenya was the first to burn ivory in 1989, then destroyed the largest amount in 2016 (105 tonnes).

Incentives

[edit]Language and rhetoric from the media on "the war on poaching" can be dehumanizing and do not provide the full picture. The reality is that many Kenyans who face poor living conditions, live in informal housing settlements, and struggle to make a liveable income, turn to poaching.[14] Aside from financial incentives, some of the main drivers for poaching are reported to be related to class, gender inequity, and uneven development across Kenya.[15] These poor conditions can be attributed to Kenya's colonial history.[16]

Illegal markets and corruption

[edit]Elephant tusks and rhino horns have high value on illegal markets. Although Kenya has many national parks and reserves protecting wildlife--elephant and rhino populations are still at risk. These threats of endangerment may be attributed to corruption within the Kenyan government and military.[17][18] An independent study investigating 743 cases between January 2008 and June 2013 reveal that those found guilty of wildlife crime were rarely getting substantially fined.[17] In many cases, corrupt government officials help poachers and trophy hunters for bribes.[18]

Although all animal hunting was banned in Kenya in 1977, trophy hunting is still allowed--for a high price. Proponents of trophy hunting in Kenya argue that the profits support conservation efforts, and that the killing of animals by humans will not decrease since many encroach on human settlements.[19] It is also argued that trophy hunting should not be banned, but rather reformed, because the animals will otherwise attack humans.[19] However, there is insufficient data to assess whether trophy hunting correlates to a decrease in animal attacks on humans.

This problem is worsened by corruption and some officials supplementing their income by permitting poaching.[20] In The Big Conservation Lie, John Mbaria and Mordecai Ogada wrote that the main problem of the crisis are not poachers, but the alienation of local people from wildlife conservation.[21] In fact, conservation is deeply rooted in the country's coloniality.[21] National parks were established and built for recreational purposes for the European settlers, thereby excluding locals.[21] Today, local populations are still being displaced from their lands through the creation of wildlife parks and conservation areas.[22] About 20% of Kenya's land are in Protected Areas (PAs), which are largely run by non-Indigenous Kenyans who earn immense profits from eco-tourism.[22] Very little of the earnings (less than $5000 USD per year) from eco-tourism go to Kenyans working in hospitality services or as wildlife rangers.[22]

Recently, as animal byproduct sales on the illegal markets increase at a high annual growth rate, new challenges arise in wildlife protection. Controversy over the construction of the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway project, constructed by the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), prompted the Chinese contractors to initiate wildlife protection efforts.[23]

Deforestation

[edit]Forestry output has also declined because of resource degradation.[24] Overexploitation over the past three decades has reduced the country's timber resources by one-half. At present only 3% of the land remains forested, and an estimated 50 square kilometres of forest are lost each year.[25] This loss of forest aggravates erosion, the silting of dams and flooding, and the loss of biodiversity.[26] Among the endangered forests are Kakamega Forest, Mau Forest and Karura Forest.[citation needed] In response to ecological disruption, activists have pressed with some success for policies that encourage sustainable resource use.[27]

Kenya is in the contient of Africa. The 2004 Nobel Peace Prize went to the Kenyan environmentalist, Wangari Maathai, best known for organizing a grassroots movement in which thousands of people were mobilized over the years to plant 30 million trees in Kenya and elsewhere and to protest forest clearance for luxury development.[28] Imprisoned as an opponent of Moi, Maathai linked deforestation with the plight of rural women, who are forced to spend untold hours in search of scarce firewood and water.[29]

Widespread poverty in many parts of the country has greatly lead to over-exploitation of the limited resources in Kenya. Cutting down of trees to create more land for cultivation, charcoal burning business, quarrying among other social and occupational practices are the major threats of environmental degradation due to poverty in rural Kenya. Regions like Murang'a, Bondo and Meru are affected by this environmental issue.[30]

Kenya had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.2/10, ranking it 133rd globally out of 172 countries.[31]

Littering and solid waste collection

[edit]

Littering and the illegal dumping of rubbish is a problem in both urban and rural Kenya. Almost all urban areas of Kenya have inadequate rubbish collection and disposal systems.[32]

Flooding

[edit]There is the risk of seasonal flooding during July to late August months. In September 2012, thousands of people were displaced in parts of Kenya's Rift Valley Province as floodwaters submerged houses and schools and destroyed crops.[33] It was especially dangerous as the floods caused latrines to overflow, contaminating numerous water sources. The floods can also cause mudslides and two children were killed in September 2012 following a mudslide in the Baringo District, which also displaced 46 families.[33]

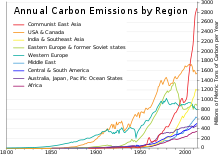

Climate change

[edit]Climate change is posing an increasing threat to global socio-[37]economic development and environmental sustainability. Developing countries with low adaptive capacity and high vulnerability to the phenomenon are disproportionately affected. Climate change in Kenya is increasingly impacting the lives of Kenya's citizens and the environment.[37] Climate Change has led to more frequent extreme weather events like droughts which last longer than usual, irregular and unpredictable rainfall, flooding and increasing temperatures.

The effects of these climatic changes have made already existing challenges with water security, food security and economic growth even more difficult. Harvests and agricultural production which account for about 33%[38] of total Gross Domestic Product (GDP)[39] are also at risk. The increased temperatures, rainfall variability in arid and semi-arid areas, and strong winds associated with tropical cyclones have combined to create favourable conditions for the breeding and migration of pests.[40] An increase in temperature of up to 2.5 °C by 2050 is predicted to increase the frequency of extreme events such as floods and droughts.[37]

Hot and dry conditions in Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASALs) make droughts or flooding brought on by extreme weather changes even more dangerous. Coastal communities are already experiencing sea level rise and associated challenges such as saltwater intrusion.[37] Lake Victoria, Lake Turkana and other lakes have significantly increased in size between 2010 and 2020[41] flooding lakeside communities.[42] All these factors impact at-risk populations like marginalized communities, women and the youth.[39]

References

[edit]- ^ "Country Profile: Kenya" (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. June 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Country Profile: Kenya" (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. June 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Jeppe Kolding | University of Bergen - Academia.edu

- ^ "Country Profile: Kenya" (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. June 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Hecky, R. E. "Kenya National Water Qu ality Synthesis Report" (PDF). Seku Repository. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ "Rare white giraffes killed by poachers in Kenya". BBC News. 2020-03-10. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- ^ Francisco Guzman; Brian Ries. "Rare white giraffes killed by poachers at Kenyan wildlife sanctuary". CNN. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- ^ Scuri, Elisabetta (17 September 2021). "Five of Kenya's iconic species are critically endangered". Retrieved 17 Feb 2022.

- ^ Nations, United. "Fighting Wildlife Trade in Kenya". United Nations. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ Douglas-Hamilton, Iain (August 1979). "AFRICAN ELEPHANT IVORY TRADE STUDY FINAL REPORT". savetheelephants.org. p. 19. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Warinwa, Fiesta; Kanga, Erastus; Kiprono, William. "Fighting Wildlife Trade in Kenya". United Nations. Retrieved 16 Feb 2022.

- ^ Duffy, Rosaleen; et al. (April 2019). "Why we must question the militarisation of conservation". Biological Conservation. 232: 66–73. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.01.013. PMC 6472544. PMID 31007267.

- ^ a b Lunstrum, Elizabeth (4 June 2014). "Green Militarization: Anti-Poaching Efforts and the Spatial Contours of Kruger National Park". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 104 (4): 816–832. doi:10.1080/00045608.2014.912545. S2CID 144921008.

- ^ Hauenstein, Severin; Kshatriya, Mrigesh; Blanc, Julian; Dormann, Carsten F.; Beale, Colin M. (28 May 2019). "African elephant poaching rates correlate with local poverty, national corruption and global ivory price". Nature Communications. 10 (2242): 2242. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.2242H. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09993-2. PMC 6538616. PMID 31138804.

- ^ Brennan, Andrew John; Kalsi, Jaslin Kaur (December 2015). "Elephant poaching & ivory trafficking problems in Sub-Saharan Africa: An application of O'Hara's principles of political economy". Ecological Economics. 120: 312–337. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.08.013.

- ^ Duffy, Rosaleen; St John, Freya A. V.; Büscher, Bram; Brockington; Dan (31 August 2015). "Toward a new understanding of the links between poverty and illegal wildlife hunting". Conservation Biology. 30 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1111/cobi.12622. PMC 5006885. PMID 26332105.

- ^ a b "Military & Corrupt Officials". Poaching Facts. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ a b Kariuki, James (2 July 2020). "Poaching fueled by corruption: Study". Nation.

- ^ a b Gregory, Andy (2 September 2019). "Banning trophy hunting won't protect animals, scientists warn". Independent. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Anderson, David; Grove, Richard H. (25 May 1990). Conservation in Africa: Peoples, Policies and Practice. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-521-34990-1. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Mbaria, John; Ogada, Mordecai (2016). The Big Conservation Lie: The Untold Story of Wildlife Conservation in Kenya. Lens&Pens Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9780692787212.

- ^ a b c Corry, Stephen (3 April 2021). "Are Kenyan Conservancies a Trojan Horse for Land Grabs?". The Elephant. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Jiang, Feng (June 2020). "Chinese contractor involvement in wildlife protection in Africa: Case study of Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway Project, Kenya". Land Use Policy. 95: 104650. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104650. ISSN 0264-8377. S2CID 216367634.

- ^ "Country Profile: Kenya" (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. June 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Country Profile: Kenya" (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. June 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Country Profile: Kenya" (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. June 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Country Profile: Kenya" (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. June 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Country Profile: Kenya" (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. June 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Country Profile: Kenya" (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. June 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-25. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ ""THE SOCIAL ECONOMIC HAZARDS OF PLASTIC PAPER BAGS LITTER IN PERI- URBAN CENTRES OF KENYA", THEURI DONALD WACHIRA, University of Nairobi, November 2013, page 20" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-24. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- ^ a b KENYA: Floods displace thousands, destroy crops, Kenya: IRIN, 2012, retrieved 5 September 2012

- ^ Hausfather, Zeke; Peters, Glen (29 January 2020). "Emissions – the 'business as usual' story is misleading". Nature. 577 (7792): 618–20. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..618H. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00177-3. PMID 31996825.

- ^ Schuur, Edward A.G.; Abbott, Benjamin W.; Commane, Roisin; Ernakovich, Jessica; Euskirchen, Eugenie; Hugelius, Gustaf; Grosse, Guido; Jones, Miriam; Koven, Charlie; Leshyk, Victor; Lawrence, David; Loranty, Michael M.; Mauritz, Marguerite; Olefeldt, David; Natali, Susan; Rodenhizer, Heidi; Salmon, Verity; Schädel, Christina; Strauss, Jens; Treat, Claire; Turetsky, Merritt (2022). "Permafrost and Climate Change: Carbon Cycle Feedbacks From the Warming Arctic". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 47: 343–371. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011847.

Medium-range estimates of Arctic carbon emissions could result from moderate climate emission mitigation policies that keep global warming below 3°C (e.g., RCP4.5). This global warming level most closely matches country emissions reduction pledges made for the Paris Climate Agreement...

- ^ Phiddian, Ellen (5 April 2022). "Explainer: IPCC Scenarios". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 20 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

"The IPCC doesn't make projections about which of these scenarios is more likely, but other researchers and modellers can. The Australian Academy of Science, for instance, released a report last year stating that our current emissions trajectory had us headed for a 3°C warmer world, roughly in line with the middle scenario. Climate Action Tracker predicts 2.5 to 2.9°C of warming based on current policies and action, with pledges and government agreements taking this to 2.1°C.

- ^ a b c d "Climate Change Profile: Kenya – Kenya". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy" (PDF). Ministry of Agriculture Livestock and Fisheries. 2019. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ a b Climate Change in Kenya focus on Children (PDF) (Report). UNICEF.

- ^ Salih, Abubakr A. M.; Baraibar, Marta; Mwangi, Kenneth Kemucie; Artan, Guleid (July 2020). "Climate change and locust outbreak in East Africa". Nature Climate Change. 10 (7): 584–585. Bibcode:2020NatCC..10..584S. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0835-8. ISSN 1758-678X. S2CID 220290864.

- ^ Tobiko, Keriako (2021). "Rising Water Levels in Kenya's Rift Valley Lakes, Turkwel Gorge Dam and Lake Victoria" (PDF). Kenya Government and UNDP. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ Baraka, Carey (2022-03-17). "A drowning world: Kenya's quiet slide underwater". the Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-17.