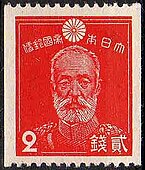

Nogi Maresuke

Nogi Maresuke | |

|---|---|

乃木 希典 | |

Nogi standing before his house in Nogizaka, Tokyo, shortly before his suicide in 1912 | |

| Governor General of Taiwan | |

| In office 14 October 1896 – 26 February 1898 | |

| Monarch | Meiji |

| Preceded by | Katsura Tarō |

| Succeeded by | Kodama Gentarō |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 25, 1849 Edo, Japan |

| Died | September 13, 1912 (aged 62) Tokyo, Japan |

| Awards |

|

| Nickname(s) | Kiten Count Nogi |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1871–1908 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | |

Count Nogi Maresuke (乃木 希典), also known as Kiten, Count Nogi GCB (December 25, 1849 – September 13, 1912), was a Japanese general in the Imperial Japanese Army and a governor-general of Taiwan. He was one of the commanders during the 1894 capture of Port Arthur from China and a prominent figure in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05, as commander of the forces which captured Port Arthur from the Russians.

He was a national hero in Imperial Japan as a model of feudal loyalty and self-sacrifice, ultimately to the point of suicide. In the Satsuma Rebellion, he lost a banner of the emperor in battle, for which he tried to atone with suicidal bravery in order to recapture it, until ordered to stop. In the Russo-Japanese War, he captured Port Arthur but he felt that he had lost too many of his soldiers, so requested permission to commit suicide, which the emperor refused. These two events, as well as his desire not to outlive his master, motivated his suicide on the day of the funeral of the Emperor Meiji. His example brought attention to the concept of bushido and the controversial samurai practice of junshi (following the lord in death).[1]

Early life

[edit]Nogi Nakito was born on December 25, 1849, at the Chōfu Domain Mansion in Edo (present-day Roppongi, Tokyo), the third son of samurai cavalry officer (umamawari) Nogi Maretsugu and his wife Hisako. His father served the Chōfu Domain, a subsidiary domain of the Chōshū Domain, and held land worth 80 koku.[2] His childhood name was Nakito (無人),[3] literally "no one", to prevent evil spirits from coming to harm him. He was briefly known as Bunzō, after which he was renamed Maresuke. As he claimed descent from the Izumo Minamoto clan through the Sasaki clan, he often used the name Minamoto no Maresuke in his signatures.[2]

Early military career

[edit]In November 1869, by the order of the Nagato domain's lord, he enlisted in Fushimi Goshin Heisha (lit. 'the Fushimi Loyal Guard Barrack') to be trained in the French style for the domanial Army. After completing the training, he was reassigned to the Kawatō Barrack in Kyoto as an instructor, and then as Toyōra domain's Army trainer in charge of coastal defense troops.

In 1871, Nogi was commissioned as a major in the fledgling Imperial Japanese Army. Around this time, he renamed himself Maresuke taking a kanji from the name of his father. In 1875, he became the 14th Infantry Regiment's attaché. The next year (1876), Nogi was named as the Kumamoto regional troop's Staff Officer, and transferred to command the 1st Infantry Regiment, and for his service in the Satsuma Rebellion, against the forces of Saigō Takamori in Kyūshū, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel on April 22, 1877. In a fierce battle at that time, he lost the 14th Infantry Regiment's regimental banner, which was considered to be the property of the Emperor, to the enemy. Its loss was an extreme disgrace. Nogi considered this such a grave mistake that he listed it as one of the reasons for his later suicide.[4]

On August 27, 1876, Nogi married Shizuko, the fourth daughter of Satsuma samurai Yuji Sadano, who was then 20 years old. As Nogi was 28 years old, it was a very late marriage for that time, considering that the average age to marry was in the early 20s. On August 28, 1877, their first son Katsunori was born, and Nogi bought his first house at Niizakamachi, Akasaka, Tokyo. In 1879, his second son Yasunori was born.[citation needed] He was promoted to colonel on April 29, 1880.

He was posted to Nagoya during the early Meiji era. The warehouse in the Sannomaru enceinte of Nagoya Castle was probably constructed in 1880 (Meiji 13) as an army ammunition depot. It was named later after him.[5]

Promoted major general on May 21, 1885, in 1887 Nogi went to Germany with Kawakami Soroku to study European military strategy and tactics.[6]

In 1894, during the First Sino-Japanese War, Major-General Nogi commanded the First Infantry Brigade which penetrated the Chinese defenses and successfully occupied Port Arthur in only one day of combat. As such, he was a senior commander during the Port Arthur massacre. The following year, he was promoted to lieutenant general (April 29, 1895) and assigned to the Second Division, tasked with the invasion of Taiwan. Nogi remained with the occupation forces in Taiwan until 1898. In 1899, he was recalled to Japan, and placed in command of the newly formed 11th Infantry Brigade, based in Kagawa.[citation needed][7]

Political career

[edit]After the war, he was elevated to danshaku (baron); and he was conferred with the Order of the Golden Kite, 1st class.[8]

Nogi was appointed as the third Japanese Governor-General of Taiwan from October 14, 1896, to February 1898. When moving to Taiwan, he moved his entire family, and during their time in Taiwan, his mother contracted malaria and died. This led Nogi to take measures to improve on the health care infrastructure of the island.

However, unlike many of his contemporaries as officers, Nogi expressed no interest in pursuing politics.[citation needed]

Russo-Japanese War

[edit]

In 1904, Nogi was recalled to active service on the occasion of the Russo-Japanese War, and was promoted to army general in command of the Japanese Third Army, with an initial strength of approximately 90,000 men and assigned to the capture of the Russian-held Port Arthur on the southern tip of Liaodong Peninsula, Manchuria. Nogi's forces landed shortly after the Battle of Nanshan, in which his eldest son, serving with the Japanese Second Army, was killed.[9] Advancing slowly down the Liaodong Peninsula, Nogi encountered unexpectedly strong resistance, and far more fortifications than he had experienced ten years earlier against the Chinese.

The attack against Port Arthur quickly turned into the lengthy Siege of Port Arthur, an engagement lasting from August 1, 1904, to January 2, 1905, costing the Japanese massive losses. Due to the mounting casualties and failure of Nogi to overcome Port Arthur's defenses, there was mounting pressure within the Japanese government and military to relieve him of command. However, in an unprecedented action, Emperor Meiji spoke out during the Supreme War Council (Japan) meeting, defending Nogi and demanding that he be kept in command.[citation needed]

After the fall of Port Arthur, Nogi was regarded as a national hero. He led his Third Army against the Russian forces at the final Battle of Mukden, ending the land combat phase of operations of the war.[10]

British historian Richard Storry noted that Nogi imposed the best of the Japanese samurai tradition on the men under his command such that "...the conduct of the Japanese during the Russo-Japanese War towards both prisoners and Chinese civilians won the respect, and indeed admiration, of the world".[11]

Both of Nogi's sons, who were army lieutenants during the war, were killed in action. Though Nogi's elder son Katsunori (August 28, 1879 – May 27, 1904) had been a sickly child, he had managed to enter the imperial military academy on his third try. He was hit in the abdomen at the Battle of Nanshan and died of blood loss while undergoing surgery at a field hospital. His second son Yasunori (December 16, 1881 – November 30, 1904), a second lieutenant at Port Arthur, fell on a rocky slope, striking his head and dying instantly. Yasunori received a posthumous promotion to lieutenant, and was buried by his father in the Aoyama cemetery.

At the end of the war, Nogi made a report directly to Emperor Meiji during a Gozen Kaigi. When explaining battles of the Siege of Port Arthur in detail, he broke down and wept, apologizing for the 56,000 lives lost in that campaign and asking to be allowed to kill himself in atonement. Emperor Meiji told him that suicide was unacceptable, as all responsibility for the war was due to imperial orders, and that Nogi must remain alive, at least as long as he himself lived.[12]

Postwar career

[edit]After the war, Nogi was elevated to the title of count and awarded the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers, Grand Cordon, 1917.[8]

As head of the Peers' School from 1908 to 1912, he was the mentor of the young Hirohito, and was, perhaps, the most important influence on the life of the future emperor of Japan.[13]

Nogi spent most of his personal fortune on hospitals for wounded soldiers and on memorial monuments erected around the country in commemoration of those killed during the Russo-Japanese War. He also successfully petitioned the Japanese government to erect a Russian-style memorial monument in Port Arthur to the Russian dead of that campaign.[citation needed]

Scouting

[edit]Nogi is significant to Scouting in Japan, as in 1911, he went to England in attendance on Prince Higashifushimi Yorihito for the coronation of King George V. The General, as the "Defender of Port Arthur" was introduced to General Robert Baden-Powell, the "Defender of Mafeking", by Lord Kitchener, whose expression "Once a Scout, always a Scout" remains to this day.

Suicide

[edit]

Nogi and his wife Shizuko committed suicide by seppuku shortly after the Emperor Meiji's funeral cortege left the palace.[14] The ritual suicide was in accordance with the samurai practice of following one's master to death (junshi).[15] In his suicide letter, he said that he wished to expiate for his disgrace in Kyūshū, and for the thousands of casualties at Port Arthur. He also donated his body to medical science.[4]

All four members of the Nogi family are buried at Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo. Under State Shinto, Nogi was revered as a kami. Nogi Shrine, a Shinto shrine in his honor, still exists on the site of his house in Nogizaka, Tokyo. His memory is also honored in other locations such as the Nogi Shrine in Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, where the mausoleum of Emperor Meiji was established.[16]

Legacy

[edit]

Nogi's seppuku immediately created a sensation and a controversy. Some writers claimed that it reflected Nogi's disgust with the profligacy and decline in moral values of late Meiji Japan. Others pointed to Nogi's own suicide note, calling it an act of atonement for mistakes in his military career. In either case, Nogi's suicide marked the end of an era, and it had a profound impact on contemporary writers, such as Mori Ōgai, Kuroiwa Ruikō and Natsume Sōseki. For the public, Nogi became a symbol of loyalty and sacrifice.

The epic historical novel Saka no Ue no Kumo portrays Nogi as floundering at the Siege of Port Arthur and having to be relieved by Kodama Gentarō. Several books have been released in recent years rehabilitating Nogi's image and showing he was a competent leader.

The Nogi Warehouse in the Sannomaru enceinte of Nagoya Castle was named after him.[17]

Man of letters

[edit]Nogi is also noted in Japan as a man of letters. His Kanshi poems (poems in the Chinese language) were especially popular among the Japanese during his time. Three of his Kanshi poems are famous.[18]

Right after the Battle of Nanshan of 1904, in which he lost his eldest son, he wrote:

| 金州城外の作 | Written Outside the Walls of Jinzhou |

|---|---|

| 山川草木轉荒涼 十里風腥新戰場 |

Mountains and rivers, trees and grass, have become cold and desolate. For ten li, the foul odor of blood drifts on the wind over new battlefields. |

After the battle of Hill 203 of 1904–05, in which he lost his second son, he wrote:

| 爾靈山 | Nireisan |

|---|---|

| 爾靈山嶮豈難攀 男子功名期克艱 |

Nireisan was indeed difficult to climb, But it was overcome by the deeds of young men. |

After the end of the Russo-Japanese War, he wrote:

| 凱旋 | Triumphant Return |

|---|---|

| 皇師百萬征強虜 野戰攻城屍作山 愧我何顔看父老 凱歌今日幾人還 |

The Emperor's army, a million strong, set out to punish the powerful savages of the north. On the battlefield, in the midst of the sieges, the bodies of the dead piled up like mountains. |

Honors

[edit]

Peerages

[edit]- 1895: Baron (August 20)

- 1907: Count (September 21)

Decorations

[edit]- 1897: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure (June 26; Second Class: April 29, 1894)

- 1906: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Kite (April 1)[8] (Third Class: August 20, 1895)

- 1906: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (April 1).[8] (Second Class: August 20, 1895; Third Class: April 7, 1885)

- 1905: Pour le Mérite (January 10)

- 1907: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (April 16)

- 1909: Chilean Gold Medal of Merit (April 28)

- 1911: Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Romania (October 25)

- 1911: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO)

- 1911: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath, Military Division (UK) (GCB) (January 1).[19]

Court order of precedence

[edit]- 1871: Senior seventh rank (December)

- 1873: Sixth rank (June 25)

- 1879: Senior sixth rank (December 20)

- 1880: Fifth rank (June 8)

- 1885: Senior fifth rank (July 25)

- 1893: Senior fourth rank (April 11)

- 1896: Third rank (December 21)

- 1904: Senior third rank (June 6)

- 1909: Second rank (July 10)

- 1916: Senior second rank (posthumous)

Portrayals

[edit]Maresuke was portrayed by Tatsuya Nakadai in the 1980 Japanese war drama film The Battle of Port Arthur (sometimes referred as 203 Kochi).[20] Directed by Toshio Masuda the film depicted the Siege of Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War and starred Nakadai as General Maresuke, Tetsurō Tamba as General Kodama Gentarō, and Toshirō Mifune as Emperor Meiji.

In the NHK television adaptation of Ryōtarō Shiba's epic Saka no Ue no Kumo, which aired from 2009 to 2011, Nogi was portrayed by actor Akira Emoto.

In the manga and NHK television adaptation of Monster, General Nogi is mentioned by the Turkish elder and community leader, Mr. Deniz, convincing the others to trust Dr. Kenzo Tenma and a local prostitute when they attempt to convince the leaders of Frankfurt's Turkish Quarter to be wary of an imminent arson attack by neo-Nazis, led by The Baby. Deniz makes reference to an incident wherein General Nogi saved an Ottoman fleet of the Turkish Navy that had run aground in the Pacific. Although this is most likely a confusion with Yamada Torajirō who did assist after the sinking of Ottoman frigate Ertuğrul.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Benesch, Oleg. (2014). Inventing the Way of the Samurai, p. 153.

- ^ a b Sasaki, Hideaki; 佐々木英昭 (2005). Nogi Maresuke : yo wa shokun no shitei o koroshitari (Shohan ed.). Mineruva Shobō. pp. 40, 113. ISBN 4-623-04406-8. OCLC 61402590.

- ^ Ōhama, Tetsuya (2010). Nogi maresuke. Kōdansha. p. 19. ISBN 978-4-06-292028-5. OCLC 744210173.

- ^ a b Bix, Herbert. (2000). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, p. 42.

- ^ "乃木倉庫 文化遺産オンライン".

- ^ National Diet Library: "Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures," Nogi Maresuke.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (December 16, 2014). 500 Great Military Leaders. ABC-CLIO. p. 560. ISBN 978-1598847574.

- ^ a b c d "Nogi, Maresuke," Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.), Vol. XXX, p. 1139.

- ^ Connaughton, Richard. (1988). Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear, p. 101.

- ^ Jukes, Geoffrey. (2002). The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905, p. 66.

- ^ Storry, Richard. (1960). A History of Modern Japan, p. 217.

- ^ Keene, Donald. (2005). Emperor of Japan, Meiji and his World, pp. 712–713.

- ^ Bix, Herbert. (2000). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, pp. 36-37, 43.

- ^ Noss, John Boyer. (1980). Man's Religions, p. 319.

- ^ Lyell, Thomas. (1948). Case History of Japan, p. 142.

- ^ Nogi Jinja Archived October 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Kyoto.

- ^ "乃木倉庫 文化遺産オンライン".

- ^ Gen. Nogi's Relics at Nogi Shrine Archived February 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Japanese)

- ^ London Gazette: Issue No. 28567, p. 1 (29 December 1911).

- ^ The Battle of Port Arthur (203 Koshi) in the Internet Movie Database

References

[edit]- Bix, Herbert P. (2000). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019314-0; OCLC 247018161

- Benesch, Oleg (2014). Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870662-5; ISBN 9780198754251; OCLC 1294862850

- Buruma, Ian. (2004). Inventing Japan: 1853–1964. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-8129-7286-3; OCLC 59228496

- Ching, Leo T.S. (2001). Becoming Japanese: Colonial Taiwan and the Politics of Identity Formation.. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22551-0; ISBN 978-0-520-22553-4; OCLC 45230397

- Connaughton, Richard. (1988). The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear: a Military History of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-05.. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-00906-5; OCLC 17983804

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Curt Johnson and David L Bongard. (1992). Encyclopedia of Military Biography. London: I. B. Tauris & Co. ISBN 978-1-85043-569-3; OCLC 59974268

- Jukes, Geoffrey. (2002). The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-446-7; OCLC 50101247

- Keene, Donald. Emperor Of Japan: Meiji And His World, 1852-1912 New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12340-2; OCLC 46731178

- Lyell, Thomas Reginald Guise. (1948). A Case History of Japan. London: Sheed & Ward. OCLC 1600274

- Noss, John Boyer. (1949). Man's Religions. New York: MacMillan. OCLC 422198957

- Storry, Richard. (1960). A History of Modern Japan. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books. OCLC 824090

- Wolferen, Karel van. (1990). The Enigma of Japanese Power: People and Politics in a Stateless Nation. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-679-72802-3; OCLC 21196393

External links

[edit]- Portrait of Nogi

- Nogi Shrine in Nogizaka, Tokyo. There is another in Shimonoseki and several others throughout Japan.

- Newspaper clippings about Nogi Maresuke in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1849 births

- 1912 suicides

- 1912 deaths

- Governors-General of Taiwan

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order

- Japanese generals

- Japanese military personnel of the Russo-Japanese War

- Japanese military personnel who died by suicide

- Japanese military personnel of the First Sino-Japanese War

- Joint suicides

- Kazoku

- Mōri retainers

- Scouting pioneers

- People from Minato

- Military personnel from Tokyo

- People of Meiji-period Japan

- People of the Boshin War

- Recipients of the Order of the Golden Kite

- Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers

- Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Treasure

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (military class)

- Scouting in Japan

- Seppuku from Meiji period to present

- Suicides by sharp instrument in Japan

- Imperial Japanese Army officers

- Japanese soldiers

- Emperor Meiji

- Deified Japanese men

- Burials at Aoyama Cemetery