Barbara Bush

Barbara Bush | |

|---|---|

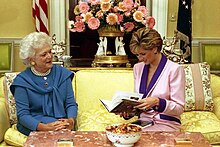

Official portrait, 1992 | |

| First Lady of the United States | |

| In role January 20, 1989 – January 20, 1993 | |

| President | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Nancy Reagan |

| Succeeded by | Hillary Clinton |

| Second Lady of the United States | |

| In role January 20, 1981 – January 20, 1989 | |

| Vice President | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Joan Mondale |

| Succeeded by | Marilyn Quayle |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Barbara Pierce June 8, 1925 Queens, New York City, U.S. |

| Died | April 17, 2018 (aged 92) Houston, Texas, U.S. |

| Resting place | George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Parent |

|

| Education | Smith College (dropped out) |

| Signature | |

Barbara Bush (née Pierce; June 8, 1925 – April 17, 2018) was the first lady of the United States from 1989 to 1993, as the wife of the 41st president of the United States, George H. W. Bush. She was previously the second lady of the United States from 1981 to 1989, and founded the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy. Among her children are George W. Bush, the 43rd president of the United States, and Jeb Bush, the 43rd governor of Florida. She and Abigail Adams are the only two women to be the wife of one U.S. president and the mother of another. At the time she became first lady, she was the second oldest woman to hold the position, behind only Anna Harrison, who never lived in the capital. Bush was generally popular as first lady, recognized for her apolitical grandmotherly image.

Barbara Pierce was born in New York City and grew up in Rye, New York. She met George H. W. Bush at the age of sixteen, and the two married in 1945. They moved to Texas in 1948, where George was successful in the oil industry and later began his political career. Bush had six children between 1946 and 1959, and she had to endure the loss of her three-year-old daughter Robin to leukemia in 1953. She lived in Washington, D.C., New York, and China while accompanying her husband in his various political roles in the 1960s and 1970s. She became an active campaigner for her husband whenever he stood for election. Bush became second lady after her husband became vice president in 1981. She took on the role of a social hostess as second lady, holding frequent events at the vice president's residence, and she traveled to many countries with her husband on his diplomatic missions.

Bush became first lady in 1989 after her husband was inaugurated as president. She enjoyed the role and life in the White House, though her experience as first lady was complicated by her protectiveness over her family and her diagnosis of Graves' disease in 1989. She frequently carried out charity work, including her projects to promote literacy and her support for people with AIDS. Among the most prominent of her actions as first lady was the commencement speech she gave at Wellesley College; it saw considerable publicity and her selection was controversial, but it was widely regarded as a success. She remained active in political campaigning after leaving the White House, as two of her sons ran for office in both gubernatorial and presidential campaigns.

Early life

[edit]Childhood

[edit]Barbara Pierce was born at Booth Memorial Hospital in Flushing, Queens in New York City on June 8, 1925, to Pauline Pierce (née Robinson) and Marvin Pierce[1][2] Her father was a businessman who worked at the McCall Corporation; he descended from the Pierce family that included U.S. president Franklin Pierce.[3] She had a close relationship with her father,[4][5] and she considered him a mentor in many aspects of her life.[6] Pierce's mother, the daughter of a Supreme Court of Ohio justice,[7] was a housewife who was involved in the gardening community.[5][6] Pierce's father descended from Robert Coe, an early Puritan colonist who founded several towns in the New England Colonies and served as a magistrate of colonial government.[8][9] Barbara was the third of her parents' four children, and she often felt overshadowed as a middle child: her older sister Martha was well liked and modeled for Vogue, her older brother Jimmy was a delinquent, and her younger brother Scott had a bone cyst that led to several surgeries throughout his childhood. Barbara felt especially neglected by her mother, with whom she often argued.[10] Noticing her mother's poor financial habits and general pessimism about her life, Barbara came to see her mother as an example to avoid, instead believing that she had to choose to be happy with what she had.[5][6] She later came to understand the ordeals faced by her mother, particularly after Barbara had a sick child of her own.[11][12]

Pierce grew up in Rye, New York, where she lived in relative comfort with servants assisting the family. She later described herself as a "very happy fat child".[4] While the family lost some of their comforts during the Great Depression, her father's successful career kept them from poverty.[10] In her youth, Pierce was athletic and enjoyed swimming, tennis, and cycling.[13] For the first years of her schooling, Pierce was a public school student, attending Milton School.[6] Insecure about her appearance as a child, she adopted a self-deprecating sense of humor and harshly judged her schoolmates. She also took on more traditionally masculine interests, such as playing football.[14] In her teenage years, she became more popular and was often sought after as a partner in her dance classes.[15] Pierce attended the Rye Country Day School from seventh to tenth grade. She then attended Ashley Hall, a boarding school in Charleston, South Carolina, for eleventh and twelfth grade.[3]

Courtship and marriage

[edit]When Pierce was 16 and on Christmas vacation, she met George H. W. Bush.[16] They met at a Christmas dance at the Greenwich Country Club, when he saw her across the room and asked a friend to introduce them.[17] After a dance together, they instead sat and talked because Bush did not know how to waltz.[18] They were immediately infatuated with one another,[19][20] and they met again, first at a dance the following night, and then when Bush agreed to play a basketball game with her brother—a game that was attended by the entire Pierce family, who all wished to see the object of her affections.[21] They kept a correspondence after Pierce returned to Ashley Hall, and they went on a date during their spring break. He then asked Pierce to accompany him to his senior prom.[22] Bush enlisted in the navy in 1942 after he graduated, and they saw each other on visits until the following year, when they were secretly engaged. Despite their original intention of secrecy, their families soon knew of it.[23] Pierce graduated from Ashley Hall in 1943.[4]

Pierce briefly attended Smith College while Bush was fighting in the Pacific theater of World War II, but she dropped out at the beginning of her second year in anticipation of their wedding.[16] While in college, she focused on the social and athletic aspects rather than her studies, as she already had the promise of a stable life after her wedding.[24][25] To support the war effort, she worked at a nuts-and-bolts factory as a gofer. While Bush was on leave, Pierce accompanied him to his family home. She took quickly to the family, and they gave her the nickname Bar, which was derived from teasingly calling her the name of the family horse, Barsil, rather than from her own name. She retained the nickname for life. In June 1944, she feared him dead after learning that his plane was shot down, but he was soon found and rescued.[17]

Pierce married Bush at the Rye First Presbyterian Church on January 6, 1945, when she was 19 years old.[26] The reception was held at The Apawamis Club, where they had gone on their first date,[27] and they had their honeymoon in Sea Island, Georgia.[4] For the first eight months of their marriage, George and Barbara Bush moved around the Eastern United States, to places including Michigan, Maryland, and Virginia, where George Bush's Navy squadron training required his presence.[13] After George was discharged, they moved to New Haven, Connecticut, and they lived in shared housing while George was attending Yale University.[4] Barbara decided not to return to college, instead working a part-time job on the Yale campus before focusing on having and raising children. Their first child, George, was born on July 6, 1946.[26]

Early married years

[edit]The Bushes moved to Texas in 1948 when George graduated from Yale,[28] as he had accepted a job in the oil industry from a family friend.[29] He did not consult Barbara before deciding on the move, and she did not raise any protest. The Bushes first lived in Odessa, Texas, where Barbara sought to set up a life in which she was not subjected to her mother's criticisms or compared to her siblings.[30] She credited this sudden lifestyle shift for prompting her to become more mature, as the distance from their families forced Barbara and George to become self-sufficient.[31][32]

The following year, the Bushes moved to California, where they lived in several different towns over the course of a year for George's work.[33] While in California, Bush learned that her mother had died in a traffic collision. To her later regret, she decided not to attend the funeral or visit her injured father in the hospital, fearing the toll that cross-country travel would take on her pregnancy. Two months later, she gave birth to her second child, Robin.[34] The Bushes then returned to Texas so George could start his own oil business, and they established a home in Midland, Texas.[28] Bush was often left alone with the children while George was away for work, sometimes for days at a time.[35] She had her third child, Jeb, in 1953.[36] While living in Texas, Bush decided to convert from Presbyterianism to her husband's denomination of Episcopalianism. However, upon taking the necessary classes, the rector congratulated her for achieving "first-class" by becoming an Episcopalian. She was so insulted by the suggestion that members of one denomination are superior to another that she left without joining, and she thereafter attended the church without anyone noticing that she was not a member.[37]

The family life established by the Bushes was interrupted in 1953 when Robin was diagnosed with leukemia. Against the advice of their physician, they took her to New York to get treatment.[36][38] Barbara forced herself to maintain her composure throughout the ordeal, and she made a point to never cry in front of her daughter. George was unable to do so and required her support. Robin died six months later, and George then had to provide support to Barbara.[39] She fell into a deep depression, in which she struggled to raise her two surviving children.[36][38] One legend held that her hair began to whiten in her grief, though she later denied this.[40] Her relationship with her husband and her oldest son helped her recover, as Bush felt she had to maintain herself for her family. She began to process her grief after overhearing George W. decline to play with the neighbors because his mother needed him.[39][41] Bush decided that she would continue having children until giving birth to another daughter.[42] She had three more children over the following years: Neil in 1955, Marvin in 1956, and Dorothy in 1959.[28]

The Bushes drove across the country in 1957, and they found themselves interrupted or barred entry wherever they went, as they were accompanied by their Black housekeeper and their Black babysitter.[43] These incidents instilled in Bush an interest in the civil rights movement.[44] The family moved to Houston in 1959, where Barbara, still pregnant with Dorothy, oversaw the construction of their new home.[38] When her son Neil was diagnosed with dyslexia in the second grade, she developed a life-long interest in literacy.[44][45]

Entering political life

[edit]1960s

[edit]

In 1962, Bush learned to campaign when her husband ran for the chairmanship of the Harris County Republican Party. She initially believed that he had been appointed to the position, only later realizing that he would need to seek election. Bush accompanied her husband as he traveled to each precinct in the county.[28][46] She grew to like campaigning, as it provided her a change of pace and gave her an opportunity to spend more time with him, though found the downtime boring and took up needlepoint to occupy herself.[47] Bush campaigned with her husband again when he ran to represent Texas in the U.S. Senate in 1964.[28] This campaign demonstrated to her a less pleasant aspect of political life, as false information was spread during her husband's primary election, alleging that her father was a communist.[48][49] While campaigning, she would sometimes hide her last name to solicit more honest feedback about her husband.[46] Bush won the primary, but he lost the general election to incumbent Ralph Yarborough. Because of her involvement with the campaign, she took his loss personally.[49]

Bush returned to the campaign trail for her husband in 1966 when he ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives,[50] and the family moved to Washington, D.C. after his victory.[46] In Washington, her primary focus was to raise her younger children and manage her household, but she also involved herself in the activities of the capital. She attended political briefings and social events,[28] and her attendance at regular events at the White House endeared her to first lady Lady Bird Johnson.[51] She also started a newspaper column, "Washington Scene", that was published in Houston.[46] Bush was active in the neighborhood where she lived, befriending prominent neighbors such as Shirley Neil Pettis, Potter Stewart, and Franklin D Roosevelt Jr.[52] The Bushes became known in Washington for the barbecues that they hosted each Sunday, a practice that they carried over from their time in Houston. Andrew Card, a member of the Bush administration, cited Barbara's hosting during this time as a significant factor in George's good relations with members of Congress during his presidency.[40]

1970s

[edit]George ran for the U.S. Senate again in 1970, and was again unsuccessful.[46] As with the previous Senate race, Barbara took an emotional toll from her husband's electoral defeat.[53] She also decided to stop dyeing her hair after her dye ran during a campaign trip, instead maintaining the white hair that would become a recognizable part of her public image.[40] After George lost his campaign, President Richard Nixon appointed him the United States ambassador to the United Nations.[13] A large apartment was provided as a residence for the UN ambassador, providing them a home in New York City.[53] She particularly enjoyed sharing this period of her husband's career, as it provided the couple with extensive social opportunities.[54] This also allowed her to form relationships with prominent diplomats.[13] While in New York, she volunteered each week at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, where her daughter had been treated for leukemia years before.[54]

Bush was against the idea of her husband becoming the chair of the Republican National Committee in 1973, but he accepted the position.[50] Instead of the opportunities of the ambassadorship, she spent her days away from her husband as he managed the fallout of the Watergate scandal. While in Washington, she reconnected with her friends from the city and attended World Affairs Council meetings.[55] When Gerald Ford became president in 1974 and asked George where he wanted to go, George asked to be appointed United States Ambassador to China.[50] He was given the position, and Barbara moved with him to China.[55] She enjoyed the time that she spent in the country and often rode bicycles with her husband to explore cities and regions that few Americans had visited.[13] As she had while a Congressman's wife in Washington, she wrote a newspaper column which was published in Texas.[56] She considered the experience to be a transformative one, allowing her to evaluate her life and sort her priorities.[57]

The Bushes returned to the United States in 1975 when George accepted a job as the U.S. Director of Central Intelligence.[55] Given the job's highly secretive nature, Barbara was completely excluded from her husband's work. With this, and the fact that her children had all moved away, she was overcome by a feeling of isolation.[58] Bush suffered from depression, which became severe enough that George suggested she seek out a mental health professional.[55] She did not take his advice, though she later regretted this.[59] Bush later cited menopause as a factor that amplified her depression, and some who knew her speculated that George's close relationship with his assistant, Jennifer Fitzgerald, was another cause.[60] Her doubts were amplified by the women's liberation movement, which made her question whether her life as a housewife was the one she wanted.[61][62] To distract herself, she began regular work at a hospice facility.[58] Barbara eventually reacquainted herself with Washington social life, and built connections for her husband's political career while she gave slideshow demonstrations to practice public speaking, giving talks about China.[63] The Bushes returned to Houston after George left the CIA in 1977.[64]

The Bushes never had a direct conversation about George running in the 1980 presidential election, but the decision was obvious to both of them, and George started his campaign in 1978.[65] Early in the campaign, there were worries that Barbara would be a liability, in part because she looked significantly older than George in a primary election where age was an issue.[66] When Barbara was asked what cause she would champion if she became first lady, she decided on literacy, believing that it would be a non-controversial choice and that it affected all other major issues.[67] Bush was a strong advocate for her husband during the campaign, though she caused a stir with the party's conservative wing when she said that she supported ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment and supported legalized abortion.[13] For two years, she traveled the country with her aide Becky Brady to campaign for her husband.[68] He did not win the Republican nomination for the presidency, but the eventual winner, Ronald Reagan, chose him as vice president. Barbara accordingly became the second lady.[67] Upon the selection of her husband as Reagan's vice presidential nominee, she promised Reagan that they were "going to work our tails off for you".[69][70]

Second Lady of the United States (1981–1989)

[edit]

Upon becoming vice president and second lady, the Bushes moved into the vice presidential residence. They lived there for the full eight years of George's tenure as vice president, longer than in any of their previous homes.[71] They renovated the house, and Barbara hosted more than one thousand social events there in her time as second lady.[72] She often ignored order of precedence so that individuals would not be regularly seated among the same group, and she would sometimes have important guests sit next to her husband instead of by her.[73] First lady Nancy Reagan grew to dislike the Bushes. During the 1980 primary election, Nancy and Barbara developed an animosity that lasted for the rest of their lives.[70] Nancy, responsible for organizing social events as first lady, reduced the social role of the vice president and the second lady. Because of this, Barbara did not take an active role in White House social events.[74]

Bush joined several associations and programs to promote literacy, her preferred social cause, though she rejected more public positions so as not to overshadow Nancy Reagan.[75][76] Bush and her initiatives in this area saw public approval.[77] She received many letters from the public, of which her white hair become such a common subject that she began using a stock reply: "Please forget about my hair. Think about my wonderful mind."[78] She also traveled extensively in the United States and abroad, both with her husband and alone while representing him. By the end of her eight years as second lady, Barbara counted 65 different nations that she had visited.[63]

Bush campaigned for her husband's reelection as vice president in the 1984 presidential campaign.[77] By the mid-1980s, Bush was comfortable speaking in front of groups, and she routinely spoke to promote issues in which she believed. She became famous for a self-deprecating sense of humor.[13] During the campaign, she made headlines when she declined to give her thoughts on vice presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro, but that "it rhymes with rich".[79] Bush panicked when it leaked that she may have referred to Ferraro as a bitch.[80] She later apologized and clarified that she meant "witch". Barbara otherwise avoided drawing attention to herself, and this was the only significant criticism of her during her tenure as second lady.[79] Throughout her tenure, she always kept George's political career in mind; after noticing that he had not appeared in any recent issues of the Republican National Committee's First Monday magazine, she orchestrated a meeting between herself and the Republican National Committee chair, and George appeared on the front cover of the following issue.[80]

Bush became a full time campaigner once again when her husband entered the 1988 presidential election to succeed Reagan.[81] Her image as a loyal wife and mother proved valuable for the campaign, especially after rumors emerged that George had engaged in an affair with his assistant Jennifer Fitzgerald.[80] The campaign at times focused on the large Bush family, and contrasted her with the incumbent first lady, Nancy Reagan, by highlighting her interest in domestic staples such as church, gardening, and time spent with family while placing less emphasis on style sense and fashion; she drew attention to both her famous white hair and disinterest in wearing designer clothes.[13] When speaking to the campaign's media advisor, she said that she would do anything for the campaign except "dye my hair, change my wardrobe, or lose weight".[82] After George became the presidential nominee, Barbara was more visible than she had previously been.[83] By this time, she felt confident enough in the world of politics to provide her own input on campaign strategy.[80] She sat in on campaign meetings, and she gave George feedback on his debate answers when they were alone.[82] It was her support for attack ads that convinced George to use them.[80] She spoke at the national party convention, becoming the third candidate's spouse to do so after Eleanor Roosevelt in 1940 and Pat Nixon in 1972.[13]

First Lady of the United States (1989–1993)

[edit]White House life and ceremonial activity

[edit]

The Bushes moved into the White House on January 20, 1989, and Barbara become the first lady of the United States.[81] She was the oldest first lady to live in the White House to that date, taking the position at age 63. The only first lady older than her to that point, Anna Harrison, did not live in Washington during her husband's term.[75] She did begin purchasing designer gowns, but this went unnoticed by the press.[84] Bush described the position of first lady as "the best job in America"[81] and "the most spoiled woman in the world".[85] Wishing to avoid the example of Nancy Reagan, Bush ensured that vice president Dan Quayle and second lady Marilyn Quayle were involved in social affairs.[45] Shortly after becoming first lady, Bush was diagnosed with Graves' disease, which gave her double vision and caused her to lose weight.[86] Both the condition and the treatment (which included methimazole, prednisone, and radiation therapy) brought her discomfort. The public was aware of her diagnosis, though she publicly denied it was seriously affecting her. Her husband was diagnosed with the same autoimmune disease in 1991.[87]

Bush loved the White House, admiring the historical significance of each room.[88] She also liked that her husband worked in the same building that they lived in, given the problems of previous years when he was often away for long periods of time.[81][89] Her day-to-day activities often included charity work, meetings, or interviews until 6pm, at which point the Bushes would host company and Barbara would give tours of the White House.[88] She also exercised in the White House pool, swimming 72 laps to complete a mile each day.[90] She sought to engage in normal activities while living in the White House, patronizing local businesses and walking her dog along Pennsylvania Avenue.[91] She believed it was important for her to leave the White House grounds during the day to avoid feeling trapped or isolated. She theorized that if she went in public enough, people in the area would grow used to her presence.[88]

Bush was generally skeptical of reporters and the press,[92] feeling that she was entitled to have a private life separately from her public life.[93] Though she did not hold regular press conferences, she worked to develop relationships with several individual reporters. When dealing with the press, she imposed her policy of "if I said it, I said it", in which her staff was not allowed to explain or justify her statements to the press.[94] Bush's press secretary, Anna Perez, was the first Black woman to hold a high ranking position in the East Wing of the White House.[95][96]

On June 1, 1990, Bush gave a commencement speech to the graduating class of Wellesley College. Her selection as speaker was controversial among students, many of whom felt that Bush was not representative of a successful woman and was only selected because of her husband's accomplishments. The controversy became a national debate.[97] Publicly, she dismissed it as "much ado about nothing" by twenty-year-olds,[98] but privately she was angered by the protest. The media attention leading up the speech was such that when the day came, it was the first speech by a first lady to ever be nationally broadcast live.[99] Bush chose to invite first lady of the Soviet Union Raisa Gorbacheva, who had a visit scheduled to the United States with her husband, to join her at the commencement.[98] Upon giving the speech, Bush was well received by the students and the public, who responded positively to her message of prioritizing personal fulfillment and relationships.[99][100]

Advocacy

[edit]

While she was first lady, Bush continued her work in promoting literacy that she had begun as second lady.[101] In March 1989, she established the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy to promote further literacy programs.[102] In 1990, she hosted the Mrs. Bush's Storytime radio program for ABC, in which she read to children.[103] Bush was known for the affection she had for her pet English Springer Spaniel, Millie, and she wrote the children's book Millie's Book about Millie's new litter of puppies in 1990.[104] The book was a best-seller, producing earnings of nearly $800,000 (equivalent to $1,865,716 in 2023). This was more money than any first lady had ever made while serving in the role. She donated the profits to her literacy foundation.[105] Bush emphasized the issue of adult illiteracy in particular, including work to increase literacy among the homeless and the incarcerated. During her time as first lady, she raised millions of dollars to fund literacy programs, including from large companies such as GM and Motorola.[45] Her interest in the subject broadly affected the administration's education policy: her advocacy contributed to the 1989 education summit, and she convinced her husband to end his opposition to the National Literacy Act of 1991, allowing it to be passed into law.[45]

Bush was an advocate for AIDS patients while first lady.[103] The issue was controversial at the time due to its association with the gay community. For this reason, her work on this issue was not as widely publicized.[106] To prevent discrimination against AIDS patients and to challenge misconceptions about its contagiousness, a photograph was published of her hugging a child with AIDS.[95][107] In private, she urged her husband to take a stronger stand on the rights of those with AIDS. She compared the discrimination faced by AIDS patients to the discomfort that people expressed when her daughter Robin had leukemia.[106]

Political involvement

[edit]

Bush was a frequent advisor to her husband, and her suggestions played a role in several of the administration's decisions, including multiple cabinet appointments.[103] A White House aide later described her as "the only voice that he 100 percent trusted".[108] She was occasionally tasked with a more formal responsibility, such as a diplomatic mission in 1990 when she represented the United States at the inauguration of Costa Rican president Rafael Calderón.[109]

In her role as first lady, Bush built a rapport with the first lady of the Soviet Union, Raisa Gorbacheva. This was credited by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, as well as other world leaders such as Helmut Kohl of Germany and Brian Mulroney of Canada, with improving Western–Soviet relations. In one discussion, Kohl assured Mikhail Gorbachev that talks between the United States and the Soviet Union would continue in part because of Barbara's influence. Bush had several relationships with global figures that were beneficial to her husband's administration, as she regularly made efforts to develop these social connections with visiting world leaders. These became especially prominent following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, where her relationship with Gorbacheva and with French president François Mitterrand eased the process of building the coalition response.[110] During the subsequent Gulf War, Bush tasked herself with making the president's job easier. She curated guest lists to avoid those who she felt would "hammer him about his conduct of the war", and she limited the messages that she passed on to him so as not to disturb him.[111]

Bush's attention shifted to her husband's reelection campaign during the 1992 presidential election, and she was invited to give a speech at the Republican National Convention.[112] She was reluctant to engage in another campaign, dreading the political attacks against her husband and her children.[87] Despite this, Bush took a major role in campaigning, more actively endorsing her husband's policy accomplishments than she previously had.[87][113] The campaign efforts were complicated by the early 1990s recession and the president's subsequent drop in approval ratings.[114]

Due to her strong approval ratings compared to her husband, Barbara was made a more prominent face of the campaign. This also allowed the campaign to contrast her with Hillary Clinton, the wife of opposing candidate Bill Clinton.[115] Bush had conflicting feelings about leaving the White House after her husband lost reelection. She was sorry to see her husband lose but relieved to return to Houston and be free from the frequent criticism of her family.[112] Bush invited Hillary Clinton to tour the White House two weeks after the election, wishing to avoid repeating the example set by Nancy Reagan, who had delayed the tour. On this tour, she gave Clinton advice to avoid the press: "They're not your friends. They're not trying to help you."[37]

Post–White House years

[edit]Retirement

[edit]Bush described January 20, 1993, the day of Bill Clinton's inauguration, as a "tough day" for her and her husband.[116] The Bushes felt that George had earned a second term as president, and Barbara blamed the press—which she accused of being pro-Clinton—for his loss.[117] She believed that they showed preference for Clinton due to his relative youth.[118] The Bushes moved back to Houston, where they lived in a rental home for nine months as they had a new house constructed.[119] This new house featured a six-foot-tall brick wall to ensure the family's privacy.[120]

The day after returning to Houston, the Bushes learned that Nancy Reagan had called into ABC News to criticize them, saying that Barbara had lied about not receiving a tour of the White House in 1988 and falsely stating that the Bushes never invited the Reagans to a state dinner. When Nancy later called Barbara to discuss the impromptu interview, Barbara decided that she "didn't feel like playing her game any more". Barbara corrected the falsehoods, and to make Nancy feel guilty, she lied by saying that reporters were harassing her because of the interview. She hung up after saying "don't you ever call me again". The two never spoke again, excepting brief formalities at state events.[121]

After spending eight years as second lady and then another four as first lady, Bush had gone some time without cooking or driving a car, two skills that she was forced to reacquire after leaving the White House.[112] Though she was able to find more opportunities for relaxation, she remained busy with her various charitable causes, public appearances, and family commitments.[116] For the first weeks of retirement, the Bushes—while still wealthy—did not have access to the funds that they once did and were surprised by the cost of living that they suddenly faced.[121] Later on, between speaking fees and a book deal, Barbara made a considerable amount of money.[112] Her book, Barbara Bush: A Memoir, was published in 1994 and stayed at the top of The New York Times Best Seller list for several weeks.[121][122] That year, two of Bush's sons sought political office: George W. ran to be the governor of Texas, and Jeb ran to be the governor of Florida. Though she helped the two of them campaign, she found that political attacks against her sons caused her even more stress than those against her husband, and she was unable to watch their respective gubernatorial debates. Jeb lost his election, and George W. was elected governor of Texas.[123] Both sons ran for the same offices again in 1998, and both won.[124]

George W. went to Barbara for advice when he was considering a presidential campaign in the 2000 presidential election. Rather than giving him an answer, she told him to make up his mind. Later, during a church sermon about accepting the call to do the right thing, she turned to her son and said "he is talking to you", and he was convinced in that moment to run for president.[125] When George W. announced his candidacy, his parents did not take a prominent role in the campaign, so as to avoid overshadowing him or making the election about the Bush political dynasty. Barbara's primary role was traveling with other women associated with the campaign in the "W Stands for Women" tour in an attempt to increase his share of the women's vote.[126] After a long legal battle over the results, her son's opponent Al Gore conceded the election,[127] and Barbara became the second woman after Abigail Adams to be both the wife and the mother of a U.S. president.[128]

President's mother

[edit]

Barbara and George were on a flight when the September 11 attacks occurred, so their plane was grounded and they were taken by the Secret Service to a motel.[129] The next day, they were given special authorization by their son to fly back to Kennebunkport, Maine.[125] They participated at a prayer service with other former presidents and first ladies on September 14. Bush later expressed that she felt great pride in her son's handling of the crisis.[129] The attack also convinced her to reinstate her own personal Secret Service protection, which she had dismissed after leaving the White House.[121]

In 2002 she became an alumna initiate of the Texas Eta chapter of Pi Beta Phi at Texas A&M University. Bush chose this university as it was the location of her husband's Presidential Library.[130] She was also a member of the Junior League of Houston.[131] In 2003, Bush published another memoir, Reflections: Life after the White House.[129]

Tensions between Iraq and the United States grew during her son's presidency, and by 2003 it seemed likely that her son would launch an invasion of Iraq. Barbara and George worried about the possibility of a war.[132] Two days before the 2003 invasion of Iraq, she spoke dismissively of television news reports about the impending conflict. Her supporters argued that she was rejecting conjecture and speculation by reporters, while her critics argued that she was being insensitive about the situation's severity.[133] After the invasion, she felt that her son was being unduly influenced by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Vice President Dick Cheney, and Chief of Staff Andy Card; she repeatedly urged him to reconsider his decisions on Iraq until he sternly rebuked her.[125]

Bush returned to campaigning during the 2004 presidential election, giving speeches on her son's behalf when he sought a second term as president. He went on to win reelection.[133] She was involved in promoting some of his policy goals in his second term, including a 2005 tour of Florida to promote his Social Security reform plan. She generated a controversy during her work supporting victims of Hurricane Katrina when she made a comment to a radio station about the situation that was deemed insensitive, saying that those affected could stay in Texas because they "were underprivileged anyway".[134] The comment was deemed insensitive and reinforced an impression that the Bushes were out of touch.[125][134]

Her involvement in the hurricane relief efforts was further criticized in 2006, when it was revealed that she donated an undisclosed amount of money to the Bush–Clinton Katrina Fund on the condition that the charity do business with an educational software company owned by her son Neil.[135] As George worked with Bill Clinton on various charity projects, the Bushs' views of their former rival softened, and he eventually came to be seen as a member of the family, though Barbara took longer to forgive Clinton's victory in the 1992 election than George did.[37]

On October 3, 2008, Bush and her husband opened the "George and Barbara Bush Center" on the University of New England waterfront Biddeford Campus.[136] The center lays the foundation for the heritage of Barbara Bush in New England and houses "The Bush Legacy Collection", material securing the Bush legacy in Maine, including memorabilia on loan from the George H. W. Bush Presidential Library at Texas A&M University. Particular attention is given to the family's New England heritage and to Barbara's love for Maine.[137]

Later life and death

[edit]

In their later years, Barbara and George spent each summer in Kennebunkport, spending the remainder of the year in Houston.[37] Bush was hospitalized for abdominal pains and underwent small intestine surgery in November 2008. In 2009, she underwent aortic valve replacement surgery.[138] In 2010, Bush was the subject of controversy when George W. recounted an anecdote that following her miscarriage she had held the fetus in a jar, causing a misconception that she had kept or displayed the remains.[139][140] In 2015, after several decades of attending Episcopalian services, she was confirmed as a member of the church so she could accept the Dean's Cross award without misrepresenting her faith.[37]

Bush was initially opposed to her son Jeb making a potential bid for the presidency, worrying that he would be weighed down by criticisms of the previous Bush presidencies and saying in 2013 that "we've had enough Bushes".[141] She recanted this statement in 2015, after Jeb began preparing his presidential campaign in the 2016 presidential election.[142][143] She campaigned for Jeb during the Republican Party primary elections, describing her son as an honest candidate while criticizing front-runner Donald Trump.[144] She was hospitalized in June 2016 after an incident involving her heart, later blaming the incident on the stress that the Trump campaign caused her. On election day, she wrote in Jeb's name. Trump was elected president, and Bush remained critical of him during his presidency.[141]

She was suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure.[145] On March 16, 2018, she fell and fractured her vertebrae and was hospitalized.[37] On April 15, her family released a statement regarding her failing health, stating that she had chosen to be at home with family, desiring comfort care rather than further medical treatment.[146] Bush died in her Houston home at the age of 92 on April 17, 2018.[147] President Donald Trump ordered flags to half-staff in her memory.[148]

Bush's casket was visited by thousands of admirers, and large crowds greeted the hearse as it passed.[108] Her funeral was held at St. Martin's Episcopal Church in Houston on April 21, 2018.[149] She was buried at the George Bush Presidential Library in College Station, Texas, beside the grave of her daughter Robin. By her request, the funeral was only 90 minutes long: a decision she made after attending the two hour funeral of Lady Bird Johnson.[37] Following Bush's death, a cartoon by Marshall Ramsey, of The Clarion-Ledger, was widely circulated, showing Barbara being greeted by Robin upon her entry to heaven.[150] Her husband died seven months later on November 30, 2018.[151]

Political beliefs

[edit]

Bush regularly spoke with her husband about political topics, including issues that he faced in the White House.[103][152] Though it was generally understood that she disagreed with him on several major political issues, she refused to speak about policy to the press.[105] Unlike her husband, she favored an assault weapons ban, though she was resistant to broader gun control as she believed that it would only restrict law-abiding citizens while criminals would subvert the law.[103]

Bush described her positions on social policy, and those of the Republican Party, as liberal, defining liberalism in this context as "caring enormously about people".[153] She increasingly disagreed with the Republican Party as its social positions became more conservative.[66] She supported causes that would support the poor and the sick, though she limited herself to those that were not politically charged.[154] She emphasized literacy because of its apolitical nature and because of her belief that illiteracy caused other societal issues.[67] Bush's friends and relatives cited the death of her daughter for informing her social beliefs, saying that she became highly empathetic for the unfortunate after Robin died.[39] She was opposed to the idea of political parties taking stances on issues such as abortion or homosexuality.[155]

Barbara's opinion on abortion was a problem for George during his political career.[66] Though early on she said that it should be limited to the first trimester, she generally refused to comment on the issue.[103] She privately reconciled her beliefs surrounding abortion during the 1980 presidential campaign, when she wrote several pages of notes referencing philosophical questions and her own personal experience with the death of a child. She concluded with the belief that the soul enters the body at birth, and that this made abortion morally permissible. She further believed that abortion should be federally funded so it was accessible to the poor and that government action to prevent unwanted births should take the form of education.[66] Only later in life did she openly state that she believed abortion was permissible.[153]

Though Bush was not an advocate for gay rights, she was not hostile to the idea as many were during her time as first lady. Her work in AIDS relief made her sympathetic to the discrimination faced by the LGBT community, and she said in response to the issue that "we cannot tolerate discrimination against any individuals or groups in our country". This was the first time that someone from the White House made a public statement in support of gay rights. While speaking in 1994, she expressed her opinion that a family caring for its children is more important than whether or not the parents were a same-sex couple. She was skeptical of the Obama administration's publicized hiring of a transgender person in 2015 until her mind was changed following a conversation with historian Timothy Naftali.[106]

Bush was skeptical of the feminist movement, in part because of the criticism that she received about her lifestyle as a housewife.[108] She supported the Equal Rights Amendment through the 1980s, though she stopped expressing public support for it while the first lady.[98] She was ambivalent about women in the military during the United States invasion of Panama, believing that women were emotionally capable of handling war but less so physically. She decided that the issue was unimportant so long as Manual Noriega was captured.[153] She more explicitly supported American action in the Gulf War,[156] and she received little pushback when she suggested that Iraqi president Saddam Hussein should be charged with war crimes and hanged.[157]

Bush opposed the rightward shift of the Republican Party following her husband's presidency.[66] When Pat Buchanan challenged her husband in the 1992 primary elections on a nationalist anti-immigration platform, she accused him of using "racist code words".[87] Bush was also highly critical of Donald Trump, dating back to 1990 before his political career. She opposed his 2016 presidential campaign and his subsequent presidency. She described her reaction to his victory as "horror", and she was confused as to how any woman could support him. After Trump's election, she was gifted a digital clock that counted down the days until the end of his term, which she kept in her bedroom. By early 2018, shortly before her death, Bush decided that she did not identify with the Republican Party as it existed at the time.[141]

Legacy

[edit]

Bush was generally popular as first lady.[45][112][158] On average, she received about 100,000 letters each year during her tenure, far more than she expected.[159] Her image as an easy going woman and a good mother was widely accepted by the American people, as was her determination to remain apolitical on policy issues.[160] This generally affable image of Bush prompted biographer Susan Page to describe her as "the most underestimated first lady of modern times".[108] Where Bush did have critics, they argued that her image as a domestic housewife conflicted with advances made in women's rights.[112] She did not meaningfully alter the role of first lady,[158] and she did not exert significant influence over the White House's social events, instead continuing the practices established by Nancy Reagan.[161] At the time of her death, two of her sons and one of her grandsons had held political office. Because of this, Bush has been described as the "matriarch" of a political dynasty. She rejected the idea of a Bush dynasty, believing that it encouraged a sense of entitlement.[162]

Bush has been contrasted with her predecessor, Nancy Reagan, in the context of image and style. Reagan was known for her fashion sense and her small figure, while Bush was recognized for her white hair and her simpler fashion.[163][164] Bush was especially known for her three-strand fake pearl necklace, which became popular among American women.[165] She described the positive reception that she received from elderly women who saw themselves in her, and she described herself as a "role model for fat ladies".[166] When contrasted with her successor, Hillary Clinton, Bush has been differentiated by her lifestyle. Clinton was criticized for the level of independence she maintained from her husband throughout her life, while Bush was criticized for a lack of independence from hers.[167] When comparing herself to previous first ladies, Bush likened herself to Eleanor Roosevelt and Bess Truman.[80] Bush was the last first lady to be raised prior to the onset of second-wave feminism, which allowed subsequent first ladies more freedom to seek an education and a career.[168]

Bush's social projects and initiatives were taken up by her children. Jeb and George both emphasized education in their political careers, while Jeb and Dorothy took control of the Barbara Bush Literacy Foundation in 2014.[45] George also cited his mother's influence when he enacted the PEPFAR initiative while president, which supported millions of AIDS patients in Africa.[106] Her granddaughter Barbara Pierce Bush co-founded Global Health Corps, which prioritizes AIDS relief as one of its primary goals.[106] Bush's personal papers, including her diaries and letters, are not scheduled to be publicly released until 35 years after her death, in 2053.[108] In 2021, while speaking at the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy's National Summit, First Lady Jill Biden said that she considers Bush to be one of her role models and a First Lady she hopes to emulate in her own role.[169]

Awards and honors

[edit]

In 1995, Bush received the Award for Greatest Public Service Benefiting the Disadvantaged, an award given out annually by the Jefferson Awards Foundation.[170] In 1997, she was the recipient of The Miss America Woman of Achievement Award for her work with literacy programs.[171] The same year, she received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[172] In 2016, she received honorary membership in Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Houston chapter.[173]

Multiple schools are named after Barbara Bush. Schools have been named Barbara Bush Elementary School in Houston; Grand Prairie, Texas; and Mesa, Arizona. Schools have been named Barbara Bush Middle School in San Antonio and Irving, Texas.[13] The Barbara Bush Children's Hospital at Maine Medical Center in Portland, Maine, was also named in her honor. Of the places that were given her name, she said that she was most proud of the "Literacy Plaza" that was under construction in Houston at the time of her death that would connect city hall with the neighboring library.[45]

Honorary degrees

[edit]Barbara Bush received honorary degrees from many institutions. These include:

| Date | School | State | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | Arcadia University | PA | Doctor of Laws (LLD)[174] |

| 1981 | Mount Vernon Seminary and College | DC | Doctor of Public Service[174] |

| May 1981 | Cardinal Stritch College | WI | Doctor of Laws (LLD)[174][175] |

| May 10, 1987 | Howard University | DC | Doctor of Humanities (DH)[176][177] |

| 1988 | Judson College | AL | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[174] |

| May 14, 1989 | Bennett College | NC | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[174][178] |

| May 21, 1989 | Boston University | MA | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[174] |

| October 6, 1989 | Morehouse School of Medicine | GA | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[174][179] |

| September 6, 1989 | Smith College | MA | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[180][181] |

| 1990 | University of Pennsylvania | PA | Doctor of Laws (LLD)[182] |

| May 1990 | University of South Carolina | SC | Doctor of Education[174][183] |

| May 19, 1990 | Saint Louis University | MO | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[184] |

| 1991 | South Carolina State College | SC | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[174] |

| 1991 | University of Michigan | MI | Doctor of Laws (LLD)[185] |

| June 15, 1991 | Northeastern University | MA | Doctor of Public Service[186] |

| May 17, 1992 | Marquette University | WI | Doctor of Laws (LLD)[187] |

| 1992 | Central State University | OH | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[174] |

| 1992 | Louisiana State University | LA | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[174] |

| 1992 | Pepperdine University | CA | Doctor of Laws (LLD)[174] |

| 1997 | Hood College | MD | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[174] |

| April 18, 1997 | Hofstra University | NY | Doctor of Humane Letters[188] |

| 1998 | Austin College | TX | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[174] |

| 1998 | University of Miami | FL | Doctor of Humanities (DH)[174] |

| 1999 | Washington College | MD | Doctor of Public Service[174] |

| 2000 | Centenary College | LA | Doctor of Laws (LLD)[174] |

| May 21, 2001 | Wake Forest University | NC | Doctor of Humanities[189] |

| March 11, 2002 | Baylor University | TX | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL)[190] |

| June 7, 2003 | University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine |

ME | Doctor of Humane Letters (LHD)[191] |

| December 16, 2005 | Texas A&M University | TX | Doctor of Humane Letters[192] |

| May 21, 2006 | George Washington University | DC | Doctor of Public Service[193] |

| May 15, 2010 | Sewanee: The University of the South | TN | Doctor of Civil Law (DCL)[194] |

Historical assessments

[edit]Since 1982 Siena College Research Institute has conducted occasional surveys asking historians to assess American first ladies according to a cumulative score on the independent criteria of their background, value to the country, intelligence, courage, accomplishments, integrity, leadership, being their own women, public image, and value to the president.[195] In terms of cumulative assessment, Bush has been ranked:

- 7th-best of 37 in 1993[196]

- 15th-best of 38 in 2003[196]

- 12th-best of 38 in 2008[196]

- 11th-best of 39 in 2014[197]

In the 2003 survey, Bush was ranked the 5th-highest in the criteria of public image.[198] In the 2008 Siena Research Institute survey, Bush was ranked the 9th-best of the twenty 20th and 21st century First Ladies.[196] In the 2014 survey, Bush and her husband were ranked the 21st-highest out of 39 first couples in terms of being a "power couple".[199] In the 2014 survey, historians ranked Bush 5th among 20th and 21st century American first ladies that they felt "could have done more".[195]

Published works

[edit]- C. Fred's Story. Doubleday. 1984. ISBN 978-0-385-18971-2.

- Millie's Book. William Morrow & Co. 1990. ISBN 978-0-688-04033-8.

- Barbara Bush: A Memoir. New York: Scribner. 1994. ISBN 978-0-02-519635-3.

- Reflections: Life After the White House. Scribner. 2004. ISBN 978-0-7432-5582-0.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Page 2019, p. [page needed].

- ^ Bush, Barbara (May 26, 2015). Barbara Bush: A Memoir. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5011-1778-7.

- ^ a b Caroli 2010, p. 285.

- ^ a b c d e Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 330.

- ^ a b c Longo 2011, p. 171.

- ^ a b c d Carlin 2016, p. 609.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Taraborrelli, J. Randy (2021). Grace & steel: Dorothy, Barbara, Laura, and the women of the Bush dynasty (First ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-24871-8.

- ^ Taraborrelli, J. Randy (2021). Grace & steel: Dorothy, Barbara, Laura, and the women of the Bush dynasty (First ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-24871-8.

- ^ a b Page 2019, Chapter 4.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "First Lady Biography: Barbara Bush". National First Ladies Library. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ Longo 2011, p. 172.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 19.

- ^ a b Caroli 2010, p. 286.

- ^ a b Page 2019, Chapter 5.

- ^ Carlin 2016, p. 610.

- ^ Gutin 2008, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Kilian 2002, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 26.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 27.

- ^ Carlin 2016, p. 611.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 30.

- ^ a b Carlin 2016, p. 612.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 331.

- ^ Kilian 2002, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Page 2019, Chapter 6.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 34.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Carlin 2016, p. 613.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Caroli 2010, p. 287.

- ^ a b c d e f g Page 2019, Chapter 23.

- ^ a b c Carlin 2016, p. 614.

- ^ a b c Page 2019, Chapter 1.

- ^ a b c Page 2019, Chapter 7.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 44.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 46.

- ^ a b Anthony 1990, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g Page 2019, Chapter 12.

- ^ a b c d e Carlin 2016, p. 615.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 65.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 66.

- ^ a b Gutin 2008, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Gutin 2008, p. 18.

- ^ Anthony 1990, p. 144.

- ^ Kilian 2002, pp. 68–70.

- ^ a b Kilian 2002, p. 73.

- ^ a b Kilian 2002, p. 74.

- ^ a b c d Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 332.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 76.

- ^ a b Gutin 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Carlin 2016, p. 616.

- ^ Page 2019, Chapter 8.

- ^ Anthony 1990, p. 255.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 78.

- ^ a b Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 333.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 80.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e Page 2019, Chapter 9.

- ^ a b c Carlin 2016, p. 617.

- ^ Kilian 2002, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Anthony 1990, p. 313.

- ^ a b Page 2019, Chapter 10.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 93.

- ^ Caroli 2010, p. 617.

- ^ Kilian 2002, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Beasley 2005, p. 189.

- ^ a b Caroli 2010, p. 289.

- ^ Anthony 1990, p. 337.

- ^ a b Gutin 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 94.

- ^ a b Carlin 2016, pp. 617–618.

- ^ a b c d e f Page 2019, Chapter 11.

- ^ a b c d Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 334.

- ^ a b Anthony 1990, p. 409.

- ^ Gutin 2008, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Beasley 2005, p. 191.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 141.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 127.

- ^ a b c d Page 2019, Chapter 16.

- ^ a b c Kilian 2002, p. 121.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 128.

- ^ Anthony 1990, pp. 423–424.

- ^ Beasley 2005, p. 185.

- ^ Beasley 2005, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Gutin 2008, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b Caroli 2010, p. 290.

- ^ Beasley 2005, p. 196.

- ^ Feinberg 1998, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c Anthony 1990, p. 434.

- ^ a b Page 2019, Chapter 14.

- ^ Feinberg 1998, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Kilian 2002, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Kilian 2002, pp. 160–161.

- ^ a b c d e f Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 335.

- ^ Carlin 2016, p. 625.

- ^ a b Caroli 2010, p. 291.

- ^ a b c d e Page 2019, Chapter 13.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e Page 2019, Introduction.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 142.

- ^ Page 2019, Chapter 15.

- ^ Kilian 2002, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b c d e f Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 336.

- ^ Carlin 2016, p. 629.

- ^ Kilian 2002, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 199.

- ^ a b Carlin 2016, p. 630.

- ^ Gutin 2008, pp. 144–146.

- ^ Beasley 2005, p. 199.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 205.

- ^ Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 337.

- ^ a b c d Page 2019, Chapter 17.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 148.

- ^ Gutin 2008, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 152.

- ^ a b c d Page 2019, Chapter 18.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 153.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 227.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 232.

- ^ a b c Gutin 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Becque, Fran (April 23, 2018). ""We walk by faith and not by sight" - Saying goodbye to Barbara Pierce Bush". Fraternity History & More. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "Notable Members - The Association of Junior Leagues International". Ajli.org. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 156.

- ^ a b Gutin 2008, p. 157.

- ^ a b Gutin 2008, p. 158.

- ^ Garza, Cynthia Leonor (March 23, 2006). "Katrina funds earmarked to pay for Neil Bush's software program". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ "The George and Barbara Bush Center". University of New England in Maine, Tangier and Online. October 3, 2008. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "Barbara Bush leaves lasting legacy in Maine". WMTW. April 17, 2018. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ "Former first lady Barbara Bush released from hospital". CNN. March 13, 2009. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ "Fetus in jar: Bush says he didn't forsee a 'national dialogue'". ABC News. November 9, 2010. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ Rochman, Bonnie (November 11, 2010). "George W. Bush, his mom and her fetus: Not so weird after all". Time. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c Page 2019, Chapter 21.

- ^ "Watch Barbara Bush tell son Jeb she's changed her mind about 'enough Bushes'". ABC News. February 14, 2015. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "Jeb wins the all-important Barbara Bush primary". Time. February 14, 2015. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Candace (February 5, 2016). "Barbara Bush brings her flair to Jeb's New Hampshire campaign". ABC News. Archived from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Ahern, Sarah (April 17, 2018). "Former First Lady Barbara Bush Dies at 92". Variety. Archived from the original on December 19, 2023. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ^ Domonoske, Camila (April 15, 2018). "Former first lady Barbara Bush in failing health, not seeking further treatment". NPR. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ "Former first lady Barbara Bush dies at age 92". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Klein, Betsy (April 18, 2018). "Trump orders flags to half-staff for Barbara Bush | CNN Politics". CNN. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny (April 21, 2018). "Barbara Bush is remembered at her funeral for her wit and tough love". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 11, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ Ramsey, Marshall (April 19, 2018). "How the Barbara Bush cartoon took on a life of its own". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 19, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ "George Bush Senior dies at the age of 94". BBC News. December 1, 2018. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ Anthony 1990, p. 426.

- ^ a b c Kilian 2002, p. 140.

- ^ Anthony 1990, pp. 428–429.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 198.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 177.

- ^ Kilian 2002, pp. 180–187.

- ^ a b Caroli 2010, p. 292.

- ^ Gutin 2008, p. 60.

- ^ Carlin 2016, p. 623.

- ^ Anthony 1990, p. 242.

- ^ Page 2019, Chapter 20.

- ^ Feinberg 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Gutin 2008, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Kilian 2002, p. 139.

- ^ Beasley 2005, p. 187.

- ^ Feinberg 1998, p. 12.

- ^ Caroli 2010, p. 293.

- ^ Chamlee, Virginia (October 21, 2021). "Jill Biden reflects on Barbara Bush and what it means to be first lady: 'Nothing can prepare you'". People. Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ "Past Winners". Jefferson Awards Foundation. Archived from the original on May 11, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Live presentation of the 77th annual Miss America Pageant". Turner Classic Movies. 1997. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". Achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "University of Houston". The Phi Beta Kappa Society. March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Bush, Barbara (2005). Reflections : life after the White House (1st Lisa Drew/Scribner trade pbk. ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster International. pp. 395–396 (appendix B). ISBN 978-0-7432-5582-0.

- ^ "Stritch Magazine" (PDF). No. Fall/Winter 2011. Cardinal Stritch University. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Recipients of honorary degrees and other university honors (by year)". Howard University. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "COMMENCEMENTS: Howard University". The New York Times. National. May 10, 1987. p. 1001029. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Donahue, Terry (May 14, 1989). "Barbara Bush receives Doctor of Humane Letters degree". UPI. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Radcliffe, Donnie (October 10, 1989). "The presidential portrait that was a bust". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees". Smith College. Archived from the original on August 14, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Kilian, Michael (September 10, 1989). "America's leading (and most-admired) college dropout-First..." Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Alphabetical Listing of Honorary Degrees". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Sexton, Megan (November 25, 2014). "Jeb Bush to speak at commencement". University of South Carolina. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "First lady gets honorary degree". Deseret News. May 20, 1990. Archived from the original on April 16, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees Awarded 1836-Present" (PDF). University of Michigan. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 22, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Photos: The life of former first lady Barbara Bush". CNN. January 20, 2017. Archived from the original on June 5, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Bickler, Jeanne (May 17, 1992). "Barbara Bush speaks to grads about family values". UPI. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Academic Convocation, Apr 18 1997 | Video". C-SPAN. April 18, 1997. 0:12:00. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "2001 - Commencement News". Commencement News. Wake Forest University. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Baylor Honors Barbara Bush With Honorary Doctorate | Media Communications". Baylor University. March 12, 2002. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Barbara Bush Receives Honorary Degree". Plainview Daily Herald. Associated Press. June 7, 2003. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Minutes of the Board of Regents of Texas A&M University" (PDF). Texas A&M University. December 16, 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- ^ "Commencement 2006". George Washington University. December 6, 2005. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Mercer, Monica (May 16, 2010). "Sewanee honors Bush, Meacham". Times Free Press. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "Eleanor Roosevelt retains top spot as America's best first lady" (PDF). scri.siena.edu. Siena Research Institute. February 15, 2014. pp. 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Ranking America's first ladies" (PDF). Siena Research Institute. December 18, 2008. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ "Siena College Research Institute/C-SPAN Study of the First Ladies of the United States 2014" (PDF). scri.siena.edu. Sienna College Research Institute/C-SPAN. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ "Ranking America's First Ladies" (PDF). scri.siena.edu. Sienna College Research Center. September 29, 2003. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "2014 Power Couple Score" (PDF). scri.siena.edu. Siena Research Institute/C-SPAN Study of the First Ladies of the United States. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

References

[edit]- Anthony, Carl Sferrazza (1990). First Ladies: The Saga of the Presidents' Wives and Their Power, 1961–1990. William Morrow and Company. ISBN 978-0-688-10562-4.

- Beasley, Maurine H. (2005). First Ladies and the Press: The Unfinished Partnership of the Media Age. Northwestern University Press. pp. 185–200. ISBN 978-0-8101-2312-0.

- Carlin, Diana B. (2016). "Barbara Pierce Bush: Choosing a Complete Life". In Sibley, Katherine A. S. (ed.). A Companion to First Ladies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 604–634. ISBN 978-1-118-73218-2.

- Caroli, Betty Boyd (2010). First Ladies: From Martha Washington to Michelle Obama. Oxford University Press. pp. 285–293. ISBN 978-0-19-539285-2.

- Feinberg, Barbara Silberdick (1998). America's First Ladies: Changing Expectations. Franklin Watts. ISBN 978-0-531-11379-0.

- Gutin, Myra G. (2008). Barbara Bush: Presidential Matriarch. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1583-4.

- Kilian, Pamela (2002). Barbara Bush: Matriarch of a Dynasty. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-31970-0.

- Longo, James McMurtry (2011). From Classroom to White House: The Presidents and First Ladies as Students and Teachers. McFarland. pp. 171–175. ISBN 978-0-7864-8846-9.

- Page, Susan (2019). The Matriarch: Barbara Bush and the Making of an American Dynasty. New York: Twelve. ISBN 978-1-5387-1364-8. OCLC 1032584246.

- Schneider, Dorothy; Schneider, Carl J. (2010). First Ladies: A Biographical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Facts on File. pp. 329–338. ISBN 978-1-4381-0815-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Radcliffe, Donnie (1989). Simply Barbara Bush: A Portrait of America's Candid First Lady. Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-36024-1.

External links

[edit]- Official White House biography of Barbara Bush

- Bush, George H. W. and Barbara Bush with Jim McGrath. George H. W. Bush and Barbara Bush Oral History, Houston Oral History Project, July 2009.

- Commencement Address at Wellesley

- Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy

- Past Winners of Harold W. McGraw, Jr. Prize in Education

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Barbara Bush at C-SPAN's First Ladies: Influence & Image

- Barbara Bush at Find a Grave

- About Barbara Bush at the Main Medical Center

- Barbara Bush

- 1925 births

- 2018 deaths

- 20th-century American Episcopalians

- 20th-century American women writers

- 21st-century American Episcopalians

- 21st-century American women

- 20th-century American memoirists

- American Episcopalians

- American people of English descent

- American women memoirists

- Burials in Texas

- Bush family

- Daughters of the American Revolution people

- First ladies of the United States

- Members of the Junior League

- Mothers of presidents of the United States

- People from Midland, Texas

- People from Rye, New York

- Rye Country Day School alumni

- Second ladies and gentlemen of the United States

- Smith College alumni

- Spouses of Texas politicians

- Texas Republicans

- Writers from Manhattan

- Writers from Texas

- Literacy advocates