Proof (2005 film)

| Proof | |

|---|---|

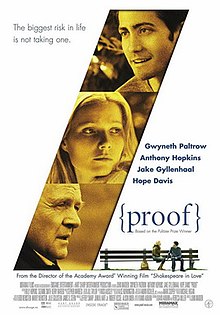

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Madden |

| Screenplay by | Rebecca Miller David Auburn |

| Based on | Proof by David Auburn |

| Produced by | Alison Owen Jeffrey Sharp John Hart |

| Starring | Gwyneth Paltrow Anthony Hopkins Jake Gyllenhaal Hope Davis |

| Cinematography | Alwin H. Küchler |

| Edited by | Mick Audsley |

| Music by | Stephen Warbeck |

| Distributed by | Miramax Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20 million |

| Box office | $14,189,860 |

Proof is a 2005 American drama film directed by John Madden and starring Gwyneth Paltrow, Anthony Hopkins, Jake Gyllenhaal, and Hope Davis. The screenplay was written by Rebecca Miller and David Auburn and based on Auburn's Pulitzer Prize-winning play of the same name.

Plot[edit]

The plot alternates between events immediately following the death of Robert, a brilliant mathematician at the University of Chicago whose genius was undone by crippling mental illness, and flashbacks revealing the life he shared with his daughter Catherine. Catherine is also a mathematician and was once a promising student at Northwestern University, but she struggles with living in her father's shadow and balancing her demanding studies with caring for her father, as well as the fear that she may have inherited his mental illness. At home, Robert clings to sanity by constantly bombarding Catherine with complex mathematical problems.

In the opening scene Robert startles Catherine while she watches TV in the middle of the night. He gives her a bottle of champagne for her birthday, and they chat for a while about the nature of insanity, ending with the revelation that Robert died last week and his funeral is tomorrow.

Awakened from this dream, Catherine realizes that Hal, a former graduate student of Robert's, is still upstairs, reading through Robert's books. Robert filled many notebooks with meaningless notes. Hal believes that Robert's genius may have withstood his illness, and clues to that genius might lie among the gibberish of his notebooks. When Hal comments on the vast amount of work Robert did, a suspicious Catherine searches Hal's backpack. Though Catherine finds nothing in Hal's bag, a notebook falls out of his coat. He explains that he wanted to give the notebook as a birthday present because it "had something written in it about her, not math, her". Hal is forced to leave, giving the notebook as intended, when Catherine calls the police.

The next day, for the funeral, Catherine's sister Claire arrives in town. A huge contrast to the unkempt Catherine, Claire is an overly put together, neurotic New Yorker. Relations between the sisters are tense, and Catherine cannot stand her sister's constant harping on matters of appearance. Catherine is also upset that Claire didn't care for her father as much as Catherine did in his final years.

At the funeral, Catherine expresses her frustration with the many people there. She interrupts the string quartet with an impromptu speech, berating everyone for not being there for her father while he was alive. She describes his descent into insanity, and that at one time he would borrow piles of books believing that aliens were sending him messages encoded in their Dewey Decimal codes. She ends by saying she is glad her father is dead and walks out of the church mid-funeral.

Claire decides to sell Robert's house back to the university and wants Catherine to come with her to New York; Catherine is upset that she will be forced to leave the house. It becomes evident that Claire suspects that Catherine may be struggling with mental illness, as their father had. A wake held at the house the night after the funeral is attended by many academic mathematicians. Hal appears and chats up Catherine. Softening up to Hal, Catherine sleeps with him.

In flashbacks, Robert is shown suddenly invigorated, believing he has seen the beginnings of a new mathematical proof that will prove his triumph over mental illness. In the present, Catherine gives Hal a key to Robert's desk and tells him to check the locked drawer for a notebook, which itself contains a lengthy but apparently very important proof. He is very excited and shows the discovery to Catherine and Claire. He asks Catherine how long she knew about this and why she did not tell him about it. She tells him that she wrote it. Catherine claims the work is hers and not her father's despite evidence to the contrary. Neither Hal nor Claire believe Catherine. Hal believes the mathematics of the proof are beyond Catherine, while Claire simply suspects that Catherine is suffering the onset of mental illness. Catherine says she can't describe the proof without the notebook because it "is not a muffin recipe". Hal decides to take it to the math department the next day to verify the proof's accuracy.

He returns as Claire and Catherine are leaving, with news that the math department believes the proof to be valid. Hal tells Claire that he doesn't think that her father wrote the proof because it employs newer mathematics and wants Catherine to explain it to him sometime. Catherine remains stung by his earlier lack of trust, and the sisters leave for the airport. Hal sprints after the car and throws the book through the window and onto Catherine's lap.

At the airport, Catherine has another flashback. It is revealed that, while living together, her father challenged her to work on math, which she does, ultimately completing a proof, which she describes in one of the many notebooks in the house. Catherine goes to tell her father about the breakthrough, but he insists she read aloud the proof that he is working on. To Catherine's disappointment, Robert's notebook contains not a proof, but a rambling and desperate observation of the passage of the seasons, that the year is divided into months of cold, months of warmth and months of indeterminate temperature, that the future of heat is the future of cold, that the future of cold is infinite, and that he will never be as cold as he will be in the future. Reading her father's work, Catherine realizes that Robert has not overcome his mental illness. A dispirited Catherine leaves her notebook in Robert's desk, where Hal will later find it.

Catherine has begun to come to terms with herself, aided by Hal's confidence in her. She decides that she does not need to go with her sister to New York and runs out of the airport. She returns to the University of Chicago, and the film ends with her and Hal meeting up on campus and discussing the proof.

Cast[edit]

- Gwyneth Paltrow as Catherine Llewellyn, the protagonist

- Anthony Hopkins as Robert Llewellyn, Catherine and Claire's father

- Jake Gyllenhaal as Hal, a former graduate student of Robert's

- Hope Davis as Claire Llewellyn, Catherine's sister, a financial analyst

Production[edit]

The film is based on the four-character stage play Proof. The film adds many bit parts for the sake of realism, and "opens up" the setting considerably. The role of Catherine was first played by Mary-Louise Parker in the play's 2000 Manhattan Theatre Club original production. Gwyneth Paltrow played Catherine in a London stage production before being cast in the film.

Hopkins' character is a mathematics professor at the University of Chicago. Although many scenes were filmed on the university's campus, the mathematics building itself (Eckhart Hall) was not used. Instead, many scenes that were set in the math building were actually shot at the Divinity School. The film opens with a pan of Gwyneth Paltrow's character bicycling across the Midway Plaisance and shows many scenes in the quadrangle before Harper Library.

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

Proof opened at #35 in its opening weekend with $193,840 and went on to gross $7,535,331 in the USA and $14,189,860 worldwide.[1]

Critical reception[edit]

Proof received generally positive reviews from film critics. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gave the film a 62% rating, with an average rating of 6.4/10, based on 143 reviews. The consensus reads, "Gwyneth Paltrow and Anthony Hopkins give exceptional performances in a film that intelligently tackles the territory between madness and genius."[2]

Awards and nominations[edit]

Gwyneth Paltrow received a Golden Globe Award nomination for Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama for Proof, but lost to Felicity Huffman for Transamerica.

The film won the Georges Delerue Award for Best Soundtrack/Sound Design at Film Fest Gent in 2005.

Mathematical relevance[edit]

Since 1993 (when Andrew Wiles first claimed to have proven Fermat's Last Theorem), there have been several feature films about mathematicians, notably Good Will Hunting (1997), A Beautiful Mind (2001), Proof (2005), Travelling Salesman (2012), The Imitation Game (2014), and Gifted (2017).

In 2006, mathematician Daniel Ullman wrote: "Of [the first] three films, Proof is the one that most realistically illustrates the world of mathematics and mathematicians." Ullman praised the director too: "Madden should be credited with capturing the feeling of the mathematical world."[3] He also called Proof: "richer and deeper, simultaneously both funnier and more serious, than either A Beautiful Mind or Good Will Hunting."[3]

Timothy Gowers of the University of Cambridge, a Fields Medalist, and Paul Sally of the University of Chicago, acted as mathematical consultants,[4] although the latter was dismissive of the film's mathematical relevance and accuracy.

Some cited mathematical concepts are Sophie Germain primes, taxicab numbers, abstract algebra, differential equations. Around minute 31 the protagonist cites by heart the number , saying that it is the largest known Germain prime. Although it is a prime and also a Sophie Germain prime, since twice that number plus one () is also prime, assuming that the film references contemporary time, by the time it was shot and projected (2004–2005) it was not the largest Sophie Germain prime, by a substantial margin.[5]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Proof (2005)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved December 21, 2013.

- ^ "Proof (2005)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Movie Review: Proof". Notices of the American Mathematical Society, March 2006, p. 340–342.

- ^ "Q & A with Paul Sally". The Chicago Maroon. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ "The Chronology of Prime Number Records". web.archive.org. 2010-10-08. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

External links[edit]

- Proof at IMDb

- Proof at Box Office Mojo

- Proof at Rotten Tomatoes

- 2005 films

- 2005 drama films

- American drama films

- Films shot at Elstree Film Studios

- British drama films

- Films about psychiatry

- Films directed by John Madden

- Films scored by Stephen Warbeck

- American films based on plays

- Films set in Chicago

- Films shot in Chicago

- Films about mathematics

- Films about grief

- Films about depression

- Films produced by Alison Owen

- Films about schizophrenia

- Georges Delerue Award winners

- Miramax films

- Cultural depictions of mathematicians

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s British films

- English-language drama films