History of China

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

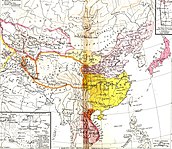

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Yellow River valley, which along with the Yangtze basin constitutes the geographic core of the Chinese cultural sphere. China maintains a rich diversity of ethnic and linguistic people groups. The traditional lens for viewing Chinese history is the dynastic cycle: imperial dynasties rise and fall, and are ascribed certain achievements. Throughout pervades the narrative that Chinese civilization can be traced as an unbroken thread many thousands of years into the past, making it one of the cradles of civilization. At various times, states representative of a dominant Chinese culture have directly controlled areas stretching as far west as the Tian Shan, the Tarim Basin, and the Himalayas, as far north as the Sayan Mountains, and as far south as the delta of the Red River.

The Neolithic period saw increasingly complex polities begin to emerge along the Yellow and Yangtze rivers. The Erlitou culture in the central plains of China is sometimes identified with the Xia dynasty (3rd millennium BCE) of traditional Chinese historiography. The earliest surviving written Chinese dates to roughly 1250 BCE, consisting of divinations inscribed on oracle bones. Chinese bronze inscriptions, ritual texts dedicated to ancestors, form another large corpus of early Chinese writing. The earliest strata of received literature in Chinese include poetry, divination, and records of official speeches. China is believed to be one of a very few loci of independent invention of writing, and the earliest surviving records display an already-mature written language. The culture remembered by the earliest extant literature is that of the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046 – 256 BCE), China's Axial Age, during which the Mandate of Heaven was introduced, and foundations laid for philosophies such as Confucianism, Taoism, Legalism, and Wuxing.

China was first united under a single imperial state by Qin Shi Huang in 221 BCE. Orthography, weights, measures, and law were all standardized. Shortly thereafter, China entered its classical era with the Han dynasty (206 BCE – CE 220), marking a critical period. A term for the Chinese language is still "Han language", and the dominant Chinese ethnic group is known as Han Chinese. The Chinese empire reached some of its farthest geographical extents during this period. Confucianism was officially sanctioned and its core texts were edited into their received forms. Wealthy landholding families independent of the ancient aristocracy began to wield significant power. Han technology can be considered on par with that of the contemporaneous Roman Empire: mass production of paper aided the proliferation of written documents, and the written language of this period was employed for millennia afterwards. China became known internationally for its sericulture. When the Han imperial order finally collapsed after four centuries, China entered an equally lengthy period of disunity, during which Buddhism began to have a significant impact on Chinese culture, while Calligraphy, art, historiography, and storytelling flourished. Wealthy families in some cases became more powerful than the central government. The Yangtze River valley was incorporated into the dominant cultural sphere.

A period of unity began in 581 with the Sui dynasty, which soon gave way to the long-lived Tang dynasty (608–907), regarded as another Chinese golden age. The Tang dynasty saw flourishing developments in science, technology, poetry, economics, and geographical influence. China's only officially recognized empress, Wu Zetian, reigned during the dynasty's first century. Buddhism was adopted by Tang emperors. "Tang people" is the other common demonym for the Han ethnic group. After the Tang fractured, the Song dynasty (960–1279) saw the maximal extent of imperial Chinese cosmopolitan development. Mechanical printing was introduced, and many of the earliest surviving witnesses of certain texts are wood-block prints from this era. Song scientific advancement led the world, and the imperial examination system gave ideological structure to the political bureaucracy. Confucianism and Taoism were fully knit together in Neo-Confucianism.

Eventually, the Mongol Empire conquered all of China, establishing the Yuan dynasty in 1271. Contact with Europe began to increase during this time. Achievements under the subsequent Ming dynasty (1368–1644) include global exploration, fine porcelain, and many extant public works projects, such as those restoring the Grand Canal and Great Wall. Three of the four Classic Chinese Novels were written during the Ming. The Qing dynasty that succeeded the Ming was ruled by ethnic Manchu people. The Qianlong emperor (r. 1735–1796) commissioned a complete encyclopaedia of imperial libraries, totaling nearly a billion words. Imperial China reached its greatest territorial extent of during the Qing, but China came into increasing conflict with European powers, culminating in the Opium Wars and subsequent unequal treaties.

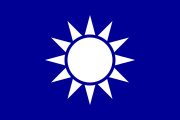

The 1911 Xinhai Revolution, led by Sun Yat-sen and others, created the modern Republic of China. From 1927 to 1949, a costly civil war roiled between the Republican government under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist-aligned Chinese Red Army, interrupted by the industrialized Empire of Japan invading the divided country until its defeat in the Second World War.

After the Communist victory, Mao Zedong proclaimed the birth of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, with the Republic retreating to Taiwan. Both governments still claim sole legitimacy of the entire mainland area. The PRC has slowly accumulated the majority of diplomatic recognition, and Taiwan's status remains disputed to this day. From 1966 to 1976, the Cultural Revolution in mainland China helped consolidate Mao's power towards the end of his life. After his death, the government began economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping, and became the world's fastest-growing major economy.[when?] China had been the most populous nation in the world for decades since its unification, until it was surpassed by India in 2023.

Prehistory

Paleolithic (1.7 Ma – 12 ka)

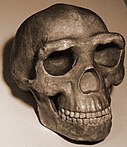

The archaic human species of Homo erectus arrived in Eurasia sometime between 1.3 and 1.8 million years ago (Ma) and numerous remains of its subspecies have been found in what is now China.[1] The oldest of these is the southwestern Yuanmou Man (元谋人; in Yunnan), dated to c. 1.7 Ma, which lived in a mixed bushland-forest environment alongside chalicotheres, deer, the elephant Stegodon, rhinos, cattle, pigs, and the giant short-faced hyena.[2] The better-known Peking Man (北京猿人; near Beijing) of 700,000–400,000 BP,[1] was discovered in the Zhoukoudian cave alongside scrapers, choppers, and, dated slightly later, points, burins, and awls.[3] Other Homo erectus fossils have been found widely throughout the region, including the northwestern Lantian Man (蓝田人; in Shaanxi) as well minor specimens in northeastern Liaoning and southern Guangdong.[1] The dates of most Paleolithic sites were long debated but have been more reliably established based on modern magnetostratigraphy: Majuangou at 1.66–1.55 Ma, Lanpo at 1.6 Ma, Xiaochangliang at 1.36 Ma, Xiantai at 1.36 Ma, Banshan at 1.32 Ma, Feiliang at 1.2 Ma and Donggutuo at 1.1 Ma.[4] Evidence of fire use by Homo erectus occurred between 1–1.8 million years BP at the archaeological site of Xihoudu, Shanxi Province.[5]

The circumstances surrounding the evolution of Homo erectus to contemporary H. sapiens is debated; the three main theories include the dominant "Out of Africa" theory (OOA), the regional continuity model and the admixture variant of the OOA hypothesis.[1] Regardless, the earliest modern humans have been dated to China at 120,000–80,000 BP based on fossilized teeth discovered in Fuyan Cave of Dao County, Hunan.[6] The larger animals which lived alongside these humans include the extinct Ailuropoda baconi panda, the Crocuta ultima hyena, the Stegodon, and the giant tapir.[6] Evidence of Middle Palaeolithic Levallois technology has been found in the lithic assemblage of Guanyindong Cave site in southwest China, dated to approximately 170,000–80,000 years ago.[7]

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age in China is considered to have begun about 10,000 years ago.[8] Because the Neolithic is conventionally defined by the presence of agriculture, it follows that the Neolithic began at different times in the various regions of what is now China. Agriculture in China developed gradually, with initial domestication of a few grains and animals gradually expanding with the addition of many others over subsequent millennia.[9] The earliest evidence of cultivated rice, found by the Yangtze River, was carbon-dated to 8,000 years ago.[10] Early evidence for millet agriculture in the Yellow River valley was radiocarbon-dated to about 7000 BC.[11] The Jiahu site is one of the best preserved early agricultural villages (7000 to 5800 BC). At Damaidi in Ningxia, 3,172 cliff carvings dating to 6000–5000 BC have been discovered, "featuring 8,453 individual characters such as the sun, moon, stars, gods and scenes of hunting or grazing", according to researcher Li Xiangshi. Written symbols, sometimes called proto-writing, were found at the site of Jiahu, which is dated around 7000 BC,[12] Damaidi around 6000 BC, Dadiwan from 5800 BC to 5400 BC,[13] and Banpo dating from the 5th millennium BC. With agriculture came increased population, the ability to store and redistribute crops, and the potential to support specialist craftsmen and administrators, which may have existed at late Neolithic sites like Taosi and the Liangzhu culture in the Yangtze delta.[10] The cultures of the middle and late Neolithic in the central Yellow River valley are known, respectively, as the Yangshao culture (5000 BC to 3000 BC) and the Longshan culture (3000 BC to 2000 BC). Pigs and dogs were the earliest-domesticated animals in the region, and after about 3000 BC domesticated cattle and sheep arrived from Western Asia. Wheat also arrived at this time but remained a minor crop. Fruit such as peaches, cherries and oranges, as well as chickens and various vegetables, were also domesticated in Neolithic China.[9]

Bronze Age

Bronze artifacts have been found at the Majiayao culture site (between 3100 and 2700 BCE).[14][15] The Bronze Age is also represented at the Lower Xiajiadian culture (2200–1600 BCE)[16] site in northeast China. Sanxingdui located in what is now Sichuan is believed to be the site of a major ancient city, of a previously unknown Bronze Age culture (between 2000 and 1200 BCE). The site was first discovered in 1929 and then re-discovered in 1986. Chinese archaeologists have identified the Sanxingdui culture to be part of the ancient kingdom of Shu, linking the artifacts found at the site to its early legendary kings.[17][18]

Ferrous metallurgy begins to appear in the late 6th century in the Yangzi Valley.[19] A bronze hatchet with a blade of meteoric iron excavated near the city of Gaocheng in Shijiazhuang (now Hebei) has been dated to the 14th century BCE. An Iron Age culture of the Tibetan Plateau has tentatively been associated with the Zhang Zhung culture described in early Tibetan writings.

Ancient China

Chinese historians in later periods were accustomed to the notion of one dynasty succeeding another, but the political situation in early China was much more complicated. Hence, as some scholars of China suggest, the Xia and the Shang can refer to political entities that existed concurrently, just as the early Zhou existed at the same time as the Shang.[20] This bears similarities to how China, both contemporaneously and later, has been divided into states that were not one region, legally or culturally.[21]

The earliest period once considered historical was the legendary era of the sage-emperors Yao, Shun, and Yu. Traditionally, the abdication system was prominent in this period,[22] with Yao yielding his throne to Shun, who abdicated to Yu, who founded the Xia dynasty.

Xia dynasty (2070–1600 BC)

The Xia dynasty of China (from c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC) is the earliest of the Three Dynasties described in ancient historical records such as Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian and Bamboo Annals. The dynasty is generally considered mythical by Western scholars, but in China it is usually associated with the early Bronze Age site at Erlitou that was excavated in Henan in 1959. Since no writing was excavated at Erlitou or any other contemporaneous site, there is not enough evidence to prove whether the Xia dynasty ever existed. Some archaeologists claim that the Erlitou site was the capital of the Xia dynasty.[23] In any case, the site of Erlitou had a level of political organization that would not be incompatible with the legends of Xia recorded in later texts.[24] More importantly, the Erlitou site has the earliest evidence for an elite who conducted rituals using cast bronze vessels, which would later be adopted by the Shang and Zhou.[25]

Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BC)

Archaeological evidence, such as oracle bones and bronzes, as well as transmitted texts attest to the historical existence of the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – 1046 BC). Findings from the earlier Shang period come from excavations at Erligang, in present-day Zhengzhou. Findings from the later Shang or Yin (殷) period, were found in profusion at Anyang, in modern-day Henan, the last of the Shang's capitals.[26] The findings at Anyang include the earliest written record of the Chinese so far discovered: inscriptions of divination records in ancient Chinese writing on the bones or shells of animals—the "oracle bones", dating from around 1250 to 1046 BC.[27]

A series of at least twenty-nine kings reigned over the Shang dynasty.[28] Throughout their reigns, according to the Shiji, the capital city was moved six times.[29] The final and most important move was to Yin during the reign of Pan Geng, around 1300 BC.[29] The term Yin dynasty has been synonymous with the Shang dynasty in history, although it has lately been used to refer specifically to the latter half of the Shang dynasty.[28]

Although written records found at Anyang confirm the existence of the Shang dynasty,[30] Western scholars are often hesitant to associate settlements that are contemporaneous with the Anyang settlement with the Shang dynasty. For example, archaeological findings at Sanxingdui suggest a technologically advanced civilization culturally unlike Anyang. The evidence is inconclusive in proving how far the Shang realm extended from Anyang. The leading hypothesis is that Anyang, ruled by the same Shang in the official history, coexisted and traded with numerous other culturally diverse settlements in the area that is now referred to as China proper.[31]

Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC)

The Zhou dynasty (1046 BC to about 256 BC) is the longest-lasting dynasty in Chinese history, though its power declined steadily over the almost eight centuries of its existence. In the late 2nd millennium BC, the Zhou dynasty arose in the Wei River valley of modern western Shaanxi Province, where they were appointed Western Protectors by the Shang. A coalition led by the ruler of the Zhou, King Wu, defeated the Shang at the Battle of Muye. They took over most of the central and lower Yellow River valley and enfeoffed their relatives and allies in semi-independent states across the region.[32] Several of these states eventually became more powerful than the Zhou kings.

The kings of Zhou invoked the concept of the Mandate of Heaven to legitimize their rule, a concept that was influential for almost every succeeding dynasty.[33] Like Shangdi, Heaven (tian) ruled over all the other gods, and it decided who would rule China.[34] It was believed that a ruler lost the Mandate of Heaven when natural disasters occurred in great number, and when, more realistically, the sovereign had apparently lost his concern for the people. In response, the royal house would be overthrown, and a new house would rule, having been granted the Mandate of Heaven.

The Zhou established two capitals Zongzhou (near modern Xi'an) and Chengzhou (Luoyang), with the king's court moving between them regularly. The Zhou alliance gradually expanded eastward into Shandong, southeastward into the Huai River valley, and southward into the Yangtze River valley.[32]

Spring and Autumn period (722–476 BC)

In 771 BC, King You and his forces were defeated in the Battle of Mount Li by rebel states and Quanrong barbarians. The rebel aristocrats established a new ruler, King Ping, in Luoyang,[35]: 4 beginning the second major phase of the Zhou dynasty: the Eastern Zhou period, which is divided into the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. The former period is named after the famous Spring and Autumn Annals. The sharply reduced political authority of the royal house left a power vacuum at the center of the Zhou culture sphere. The Zhou kings had delegated local political authority to hundreds of settlement states, some of them only as large as a walled town and surrounding land. These states began to fight against one another and vie for hegemony. The more powerful states tended to conquer and incorporate the weaker ones, so the number of states declined over time.[36] By the 6th century BC most small states had disappeared by being annexed and just a few large and powerful principalities remained. Some southern states, such as Chu and Wu, claimed independence from the Zhou, who undertook wars against some of them (Wu and Yue). Many new cities were established in this period and society gradually became more urbanized and commercialized. Many famous individuals such as Laozi, Confucius and Sun Tzu lived during this chaotic period.

Conflict in this period occurred both between and within states. Warfare between states forced the surviving states to develop better administrations to mobilize more soldiers and resources. Within states there was constant jockeying between elite families. For example, the three most powerful families in the Jin state—Zhao, Wei and Han—eventually overthrew the ruling family and partitioned the state between them.

The Hundred Schools of Thought of classical Chinese philosophy began blossoming during this period and the subsequent Warring States period. Such influential intellectual movements as Confucianism, Taoism, Legalism and Mohism were founded, partly in response to the changing political world. The first two philosophical thoughts would have an enormous influence on Chinese culture.

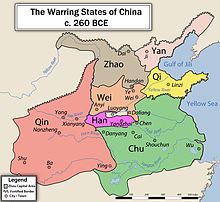

Warring States period (476–221 BC)

After further political consolidations, seven prominent states remained during the 5th century BC. The years in which these states battled each other is known as the Warring States period. Though the Zhou king nominally remained as such until 256 BC, he was largely a figurehead that held little real power.

Numerous developments were made during this period in the areas of culture and mathematics—including the Zuo Zhuan within the Spring and Autumn Annals (a literary work summarizing the preceding Spring and Autumn period), and the bundle of 21 bamboo slips from the Tsinghua collection, dated to 305 BC—being the world's earliest known example of a two-digit, base-10 multiplication table. The Tsinghua collection indicates that sophisticated commercial arithmetic was already established during this period.[37]

As neighboring territories of the seven states were annexed (including areas of modern Sichuan and Liaoning), they were now to be governed under an administrative system of commanderies and prefectures. This system had been in use elsewhere since the Spring and Autumn period, and its influence on administration would prove resilient—its terminology can still be seen in the contemporaneous sheng and xian ("provinces" and "counties") of contemporary China.

The state of Qin became dominant in the waning decades of the Warring States period, conquering the Shu capital of Jinsha on the Chengdu Plain; and then eventually driving Chu from its place in the Han River valley. Qin imitated the administrative reforms of the other states, thereby becoming a powerhouse.[9] Its final expansion began during the reign of Ying Zheng, ultimately unifying the other six regional powers, and enabling him to proclaim himself as China's first emperor—known to history as Qin Shi Huang.

Imperial China

Early imperial China

Qin dynasty (221–206 BC)

Ying Zheng's establishment of the Qin dynasty (秦朝) in 221 BC effectively formalised the region as a true empire for the first time in Chinese history, rather than a state, and its pivotal status probably led to "Qin" (秦) later evolving into the Western term "China".[38] To emphasise his sole rule, Zheng proclaimed himself Shi Huangdi (始皇帝; "First August Emperor"); the Huangdi title, derived from Chinese mythology, became the standard for subsequent rulers.[39][a] Based in Xianyang, the empire was a centralized bureaucratic monarchy, a governing scheme which dominated the future of Imperial China.[41][42] In an effort to improve the Zhou's perceived failures, this system consisted of more than 36 commanderies (郡; jun),[b] made up of counties (县; xian) and progressively smaller divisions, each with a local leader.[45]

Many aspects of society were informed by Legalism, a state ideology promoted by the emperor and his chancellor Li Si that was introduced at an earlier time by Shang Yang.[46] In legal matters this philosophy emphasised mutual responsibility in disputes and severe punishments for crime, while economic practices included the general encouragement of agriculture and repression of trade.[46] Reforms occurred in weights and measures, writing styles (seal script) and metal currency (Ban Liang), all of which were standardized.[47][48] Traditionally, Qin Shi Huang is regarded as ordering a mass burning of books and the live burial of scholars under the guise of Legalism, though contemporary scholars express considerable doubt on the historicity of this event.[46] Despite its importance, Legalism was probably supplemented in non-political matters by Confucianism for social and moral beliefs and the five-element Wuxing (五行) theories for cosmological thought.[49]

The Qin administration kept exhaustive records on their population, collecting information on their sex, age, social status and residence.[50] Commoners, who made up over 90% of the population,[51] "suffered harsh treatment" according to the historian Patricia Buckley Ebrey, as they were often conscripted into forced labor for the empire's construction projects.[52] This included a massive system of imperial highways in 220 BC, which ranged around 4,250 miles (6,840 km) altogether.[53] Other major construction projects were assigned to the general Meng Tian, who concurrently led a successful campaign against the northern Xiongnu peoples (210s BC), reportedly with 300,000 troops.[53][c] Under Qin Shi Huang's orders, Meng supervised the combining of numerous ancient walls into what came to be known as the Great Wall of China and oversaw the building of a 500 miles (800 km) straight highway between northern and southern China.[55] The emperor also oversaw the construction of his monumental mausoleum, which includes the well known Terracotta Army.[56]

After Qin Shi Huang's death the Qin government drastically deteriorated and eventually capitulated in 207 BC after the Qin capital was captured and sacked by rebels, which would ultimately lead to the establishment of the Han Empire.[57][58]

Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220)

Western Han

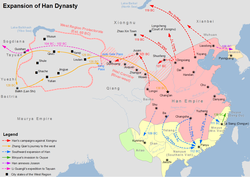

The Han dynasty was founded by Liu Bang, who emerged victorious in the Chu–Han Contention that followed the fall of the Qin dynasty. A golden age in Chinese history, the Han dynasty's long period of stability and prosperity consolidated the foundation of China as a unified state under a central imperial bureaucracy, which was to last intermittently for most of the next two millennia. During the Han dynasty, territory of China was extended to most of the China proper and to areas far west. Confucianism was officially elevated to orthodox status and was to shape the subsequent Chinese civilization. Art, culture and science all advanced to unprecedented heights. With the profound and lasting impacts of this period of Chinese history, the dynasty name "Han" had been taken as the name of the Chinese people, now the dominant ethnic group in modern China, and had been commonly used to refer to Chinese language and written characters.

After the initial laissez-faire policies of Emperors Wen and Jing, the ambitious Emperor Wu brought the empire to its zenith. To consolidate his power, he disenfranchised the majority of imperial relatives, appointing military governors to control their former lands.[59] As a further step, he extended patronage to Confucianism, which emphasizes stability and order in a well-structured society. Imperial Universities were established to support its study. At the urging of his Legalist advisors, however, he also strengthened the fiscal structure of the dynasty with government monopolies.

Right image: Reverse side of a Western-Han bronze mirror with painted designs of a flower motif

Major military campaigns were launched to weaken the nomadic Xiongnu Empire, limiting their influence north of the Great Wall. Along with the diplomatic efforts led by Zhang Qian, the sphere of influence of the Han Empire extended to the states in the Tarim Basin, opened up the Silk Road that connected China to the west, stimulating bilateral trade and cultural exchange. To the south, various small kingdoms far beyond the Yangtze River Valley were formally incorporated into the empire.

Emperor Wu also dispatched a series of military campaigns against the Baiyue tribes. The Han annexed Minyue in 135 BC and 111 BC, Nanyue in 111 BC, and Dian in 109 BC.[60] Migration and military expeditions led to the cultural assimilation of the south.[61] It also brought the Han into contact with kingdoms in Southeast Asia, introducing diplomacy and trade.[62]

After Emperor Wu the empire slipped into gradual stagnation and decline. Economically, the state treasury was strained by excessive campaigns and projects, while land acquisitions by elite families gradually drained the tax base. Various consort clans exerted increasing control over strings of incompetent emperors and eventually the dynasty was briefly interrupted by the usurpation of Wang Mang.

Xin dynasty

In AD 9 the usurper Wang Mang claimed that the Mandate of Heaven called for the end of the Han dynasty and the rise of his own, and he founded the short-lived Xin dynasty. Wang Mang started an extensive program of land and other economic reforms, including the outlawing of slavery and land nationalization and redistribution. These programs, however, were never supported by the landholding families, because they favored the peasants. The instability of power brought about chaos, uprisings, and loss of territories. This was compounded by mass flooding of the Yellow River; silt buildup caused it to split into two channels and displaced large numbers of farmers. Wang Mang was eventually killed in Weiyang Palace by an enraged peasant mob in AD 23.

Eastern Han

Emperor Guangwu reinstated the Han dynasty with the support of landholding and merchant families at Luoyang, east of the former capital Xi'an. Thus, this new era is termed the Eastern Han dynasty. With the capable administrations of Emperors Ming and Zhang, former glories of the dynasty were reclaimed, with brilliant military and cultural achievements. The Xiongnu Empire was decisively defeated. The diplomat and general Ban Chao further expanded the conquests across the Pamirs to the shores of the Caspian Sea,[63]: 175 thus reopening the Silk Road, and bringing trade, foreign cultures, along with the arrival of Buddhism. With extensive connections with the west, the first of several Roman embassies to China were recorded in Chinese sources, coming from the sea route in AD 166, and a second one in AD 284.

The Eastern Han dynasty was one of the most prolific eras of science and technology in ancient China, notably the historic invention of papermaking by Cai Lun, and the numerous scientific and mathematical contributions by the famous polymath Zhang Heng.

Six Dynasties

Three Kingdoms (AD 220–280)

By the 2nd century, the empire declined amidst land acquisitions, invasions, and feuding between consort clans and eunuchs. The Yellow Turban Rebellion broke out in AD 184, ushering in an era of warlords. In the ensuing turmoil, three states emerged, trying to gain predominance and reunify the land, giving this historical period its name. The classic historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms dramatizes events of this period.

The warlord Cao Cao reunified the north in 208, and in 220 his son accepted the abdication of Emperor Xian of Han, thus initiating the Wei dynasty. Soon, Wei's rivals Shu and Wu proclaimed their independence. This period was characterized by a gradual decentralization of the state that had existed during the Qin and Han dynasties, and an increase in the power of great families.

In 266, the Jin dynasty overthrew the Wei and later unified the country in 280, but this union was short-lived.

Jin dynasty (AD 266–420)

The Jin dynasty reunited China proper for the first time since the end of the Han dynasty, ending the Three Kingdoms era. However, the Jin dynasty was severely weakened by War of the Eight Princes and lost control of northern China after non-Han Chinese settlers rebelled and captured Luoyang and Chang'an. In 317, the Jin prince Sima Rui, based in modern-day Nanjing, became emperor and continued the dynasty, now known as the Eastern Jin, which held southern China for another century. Prior to this move, historians refer to the Jin dynasty as the Western Jin.

Sixteen Kingdoms (AD 304–439)

Northern China fragmented into a series of independent states known as the Sixteen Kingdoms, most of which were founded by Xiongnu, Xianbei, Jie, Di and Qiang rulers. These non-Han peoples were ancestors of the Turks, Mongols, and Tibetans. Many had, to some extent, been "sinicized" long before their ascent to power. In fact, some of them, notably the Qiang and the Xiongnu, had already been allowed to live in the frontier regions within the Great Wall since late Han times. During this period, warfare ravaged the north and prompted large-scale Han Chinese migration south to the Yangtze River Basin and Delta.

Northern and Southern dynasties (AD 420–589)

In the early 5th century China entered a period known as the Northern and Southern dynasties, in which parallel regimes ruled the northern and southern halves of the country. In the south, the Eastern Jin gave way to the Liu Song, Southern Qi, Liang and finally Chen. Each of these Southern dynasties were led by Han Chinese ruling families and used Jiankang (modern Nanjing) as the capital. They held off attacks from the north and preserved many aspects of Chinese civilization, while northern barbarian regimes began to sinify.

In the north the last of the Sixteen Kingdoms was extinguished in 439 by the Northern Wei, a kingdom founded by the Xianbei, a nomadic people who unified northern China. The Northern Wei eventually split into the Eastern and Western Wei, which then became the Northern Qi and Northern Zhou. These regimes were dominated by Xianbei or Han Chinese who had married into Xianbei families. During this period most Xianbei people adopted Han surnames, eventually leading to complete assimilation into the Han.

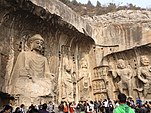

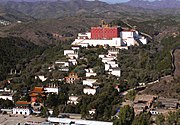

Despite the division of the country, Buddhism spread throughout the land. In southern China, fierce debates about whether Buddhism should be allowed were held frequently by the royal court and nobles. By the end of the era, Buddhists and Taoists had become much more tolerant of each other.[64]

Mid-imperial China

Sui dynasty (581–618)

The short-lived Sui dynasty was a pivotal period in Chinese history. Founded by Emperor Wen in 581 in succession of the Northern Zhou, the Sui went on to conquer the Southern Chen in 589 to reunify China, ending three centuries of political division. The Sui pioneered many new institutions, including the government system of Three Departments and Six Ministries, imperial examinations for selecting officials from commoners, while improved on the systems of fubing system of the army conscription and the equal-field system of land distributions. These policies, which were adopted by later dynasties, brought enormous population growth, and amassed excessive wealth to the state. Standardized coinage was enforced throughout the unified empire. Buddhism took root as a prominent religion and was supported officially. Sui China was known for its numerous mega-construction projects. Intended for grains shipment and transporting troops, the Grand Canal was constructed, linking the capitals Daxing (Chang'an) and Luoyang to the wealthy southeast region, and in another route, to the northeast border. The Great Wall was also expanded, while series of military conquests and diplomatic maneuvers further pacified its borders. However, the massive invasions of the Korean Peninsula during the Goguryeo–Sui War failed disastrously, triggering widespread revolts that led to the fall of the dynasty.

Tang dynasty (618–907)

The Tang dynasty was a golden age of Chinese civilization, a prosperous, stable, and creative period with significant developments in culture, art, literature, particularly poetry, and technology. Buddhism became the predominant religion for the common people. Chang'an (modern Xi'an), the national capital, was the largest city in the world during its time.[65]

The first emperor, Emperor Gaozu, came to the throne on 18 June 618, placed there by his son, Li Shimin, who became the second emperor, Taizong, one of the greatest emperors in Chinese history. Combined military conquests and diplomatic maneuvers reduced threats from Central Asian tribes, extended the border, and brought neighboring states into a tributary system. Military victories in the Tarim Basin kept the Silk Road open, connecting Chang'an to Central Asia and areas far to the west. In the south, lucrative maritime trade routes from port cities such as Guangzhou connected with distant countries, and foreign merchants settled in China, encouraging a cosmopolitan culture. The Tang culture and social systems were observed and adapted by neighboring countries, most notably Japan. Internally the Grand Canal linked the political heartland in Chang'an to the agricultural and economic centers in the eastern and southern parts of the empire. Xuanzang, a Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveller, and translator travelled to India on his own and returned with "over six hundred Mahayana and Hinayana texts, seven statues of the Buddha and more than a hundred sarira relics."

The prosperity of the early Tang dynasty was abetted by a centralized bureaucracy. The government was organized as "Three Departments and Six Ministries" to separately draft, review, and implement policies. These departments were run by royal family members and landed aristocrats, but as the dynasty wore on, were joined or replaced by scholar officials selected by imperial examinations, setting patterns for later dynasties.

Under the Tang "equal-field system" all land was owned by the Emperor and granted to each family according to household size. Men granted land were conscripted for military service for a fixed period each year, a military policy known as the fubing system. These policies stimulated a rapid growth in productivity and a significant army without much burden on the state treasury. By the dynasty's midpoint, however, standing armies had replaced conscription, and land was continuously falling into the hands of private owners and religious institutions granted exemptions.

The dynasty continued to flourish under the rule of Empress Wu Zetian, the only official empress regnant in Chinese history, and reached its zenith during the long reign of Emperor Xuanzong, who oversaw an empire that stretched from the Pacific to the Aral Sea with at least 50 million people. There were vibrant artistic and cultural creations, including works of the greatest Chinese poets, Li Bai and Du Fu.

At the zenith of prosperity of the empire, the An Lushan Rebellion from 755 to 763 was a watershed event. War, disease, and economic disruption devastated the population and drastically weakened the central imperial government. Upon suppression of the rebellion, regional military governors, known as jiedushi, gained increasingly autonomous status as the central government lost its ability to control them. With loss of revenue from land tax, the central imperial government came to rely heavily on its salt monopoly. Externally, former submissive states raided the empire and the vast border territories were lost for centuries. Nevertheless, civil society recovered and thrived amidst the weakened imperial bureaucracy.

In late Tang period the empire was worn out by recurring revolts of the regional military governors, while scholar-officials engaged in fierce factional strife and corrupted eunuchs amassed immense power. Catastrophically, the Huang Chao Rebellion, from 874 to 884, devastated the entire empire for a decade. The sack of the southern port Guangzhou in 879 was followed by the massacre of most of its inhabitants, especially the large foreign merchant enclaves.[67][68] By 881, both capitals, Luoyang and Chang'an, fell successively. The reliance on ethnic Han and Turkic warlords in suppressing the rebellion increased their power and influence. Consequently, the fall of the dynasty following Zhu Wen's usurpation led to an era of division.

In 808, 30,000 Shatuo under Zhuye Jinzhong defected from the Tibetans to Tang China and the Tibetans punished them by killing Zhuye Jinzhong as they were chasing them.[69] The Uyghurs also fought against an alliance of Shatuo and Tibetans at Beshbalik.[70] The Shatuo Turks under Zhuye Chixin (Li Guochang) served the Tang dynasty in fighting against their fellow Turkic people in the Uyghur Khaganate. In 839, when the Uyghur khaganate (Huigu) general Jueluowu (掘羅勿) rose against the rule of then-reigning Zhangxin Khan, he elicited the help from Zhuye Chixin by giving Zhuye 300 horses, and together, they defeated Zhangxin Khan, who then committed suicide, precipitating the subsequent collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate. In the next few years, when Uyghur Khaganate remnants tried to raid Tang borders, the Shatuo participated extensively in counterattacking the Uyghur Khaganate with other tribes loyal to Tang.[71] In 843, Zhuye Chixin, under the command of the Han Chinese officer Shi Xiong with Tuyuhun, Tangut and Han Chinese troops, participated in a raid against the Uyghur khaganate that led to the slaughter of Uyghur forces at Shahu mountain.[72]

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907–960)

The period of political disunity between the Tang and the Song, known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, lasted from 907 to 960. During this half-century, China was in all respects a multi-state system. Five regimes, namely, (Later) Liang, Tang, Jin, Han and Zhou, rapidly succeeded one another in control of the traditional Imperial heartland in northern China. Among the regimes, rulers of (Later) Tang, Jin and Han were sinicized Shatuo Turks, which ruled over an ethnic majority of Han Chinese in the north. More stable and smaller regimes of mostly ethnic Han rulers coexisted in south and western China over the period, cumulatively constituted the "Ten Kingdoms".

Amidst political chaos in the north, the strategic Sixteen Prefectures (region along today's Great Wall) were ceded to the emerging Khitan Liao dynasty, which drastically weakened the defense of China proper against northern nomadic empires. To the south, Vietnam gained lasting independence after being a Chinese prefecture for many centuries. With wars dominating in Northern China, there were mass southward migrations of population, which further enhanced the southward shift of cultural and economic centers in China. The era ended with the coup of Later Zhou general Zhao Kuangyin, and the establishment of the Song dynasty in 960, which eventually annihilated the remains of the "Ten Kingdoms" and reunified China.

Late imperial China

Song, Liao, Jin, and Western Xia dynasties (960–1279)

In 960, the Song dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu, with its capital established in Kaifeng (then known as Bianjing). In 979, the Song dynasty reunified most of China proper, while large swaths of the outer territories were occupied by sinicized nomadic empires. The Khitan Liao dynasty, which lasted from 907 to 1125, ruled over Manchuria, Mongolia, and parts of Northern China. Meanwhile, in what are now the north-western Chinese provinces of Gansu, Shaanxi, and Ningxia, the Tangut tribes founded the Western Xia dynasty from 1032 to 1227.

Aiming to recover the strategic sixteen prefectures lost in the previous dynasty, campaigns were launched against the Liao dynasty in the early Song period, which all ended in failure. Then in 1004, the Liao cavalry swept over the exposed North China Plain and reached the outskirts of Kaifeng, forcing the Song's submission and then agreement to the Chanyuan Treaty, which imposed heavy annual tributes from the Song treasury. The treaty was a significant reversal of Chinese dominance of the traditional tributary system. Yet the annual outflow of Song's silver to the Liao was paid back through the purchase of Chinese goods and products, which expanded the Song economy, and replenished its treasury. This dampened the incentive for the Song to further campaign against the Liao. Meanwhile, this cross-border trade and contact induced further sinicization within the Liao Empire, at the expense of its military might which was derived from its nomadic lifestyle. Similar treaties and social-economical consequences occurred in Song's relations with the Jin dynasty.

Within the Liao Empire the Jurchen tribes revolted against their overlords to establish the Jin dynasty in 1115. In 1125, the devastating Jin cataphract annihilated the Liao dynasty, while remnants of Liao court members fled to Central Asia to found the Qara Khitai Empire (Western Liao dynasty). Jin's invasion of the Song dynasty followed swiftly. In 1127, Kaifeng was sacked, a massive catastrophe known as the Jingkang Incident, ending the Northern Song dynasty. Later the entire north of China was conquered. The survived members of Song court regrouped in the new capital city of Hangzhou, and initiated the Southern Song dynasty, which ruled territories south of the Huai River. In the ensuing years, the territory and population of China were divided between the Song dynasty, the Jin dynasty and the Western Xia dynasty. The era ended with the Mongol conquest, as Western Xia fell in 1227, the Jin dynasty in 1234, and finally the Southern Song dynasty in 1279.

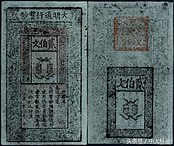

Despite its military weakness, the Song dynasty is widely considered to be the high point of classical Chinese civilization. The Song economy, facilitated by technological advancement, had reached a level of sophistication probably unseen in world history before its time. The population soared to over 100 million and the living standards of common people improved tremendously due to improvements in rice cultivation and the wide availability of coal for production. The capital cities of Kaifeng and subsequently Hangzhou were both the most populous cities in the world for their time, and encouraged vibrant civil societies unmatched by previous Chinese dynasties. Although land trading routes to the far west were blocked by nomadic empires, there was extensive maritime trade with neighbouring states, such as in South-east Asia, which facilitated the use of Song coinage as the de facto currency of exchange. Giant wooden vessels equipped with compasses traveled throughout the China Seas and northern Indian Ocean. The concept of insurance was practised by merchants to hedge the risks of such long-haul maritime shipments. With prosperous economic activities, the historically first use of paper currency emerged in the western city of Chengdu, as a cheaper supplement to the existing copper coins.

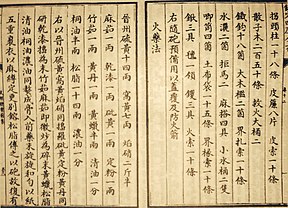

The Song dynasty was considered to be the golden age of great advancements in science and technology of China, thanks to innovative scholar-officials such as Su Song (1020–1101) and Shen Kuo (1031–1095). Inventions such as the hydro-mechanical astronomical clock, the first continuous and endless power-transmitting chain, woodblock printing and paper money were all invented during the Song dynasty, further cementing its status.

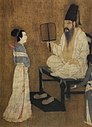

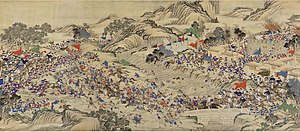

There was court intrigue between the political reformers and conservatives, led by the chancellors Wang Anshi and Sima Guang, respectively. By the mid-to-late 13th century, the Chinese had adopted the dogma of Neo-Confucian philosophy formulated by Zhu Xi. Enormous literary works were compiled during the Song dynasty, such as the innovative historical narrative Zizhi Tongjian ("Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government"). The invention of movable-type printing further facilitated the spread of knowledge. Culture and the arts flourished, with grandiose artworks such as Along the River During the Qingming Festival and Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute, along with great Buddhist painters such as the prolific Lin Tinggui.

The Song dynasty was also a period of major innovation in the history of warfare. Gunpowder, while invented in the Tang dynasty, was first put into practical use on the battlefield by the Song army, inspiring a succession of new firearms and siege engines designs. During the Southern Song dynasty, as its survival hinged decisively on guarding the Yangtze and Huai River against the cavalry forces from the north, the first standing navy in China was assembled in 1132, with its admiral's headquarters established at Dinghai. Paddle-wheel warships equipped with trebuchets could launch incendiary bombs made of gunpowder and lime to effect, as recorded in Song's victory over the invading Jin forces at the Battle of Tangdao in the East China Sea, and the Battle of Caishi on the Yangtze River in 1161.

The advances in civilisation during the Song dynasty came to an abrupt end following the devastating Mongol conquest of the North and subsequently other areas of the empire, during which the population sharply dwindled, with a marked contraction in economy. Despite viciously halting Mongol advances for more than three decades, the Southern Song capital Hangzhou fell in 1276, followed by the final annihilation of the Song standing navy at the Battle of Yamen in 1279.

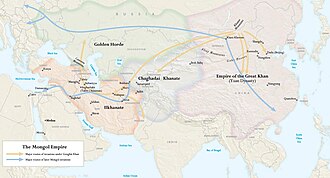

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)

The Yuan dynasty was formally proclaimed in 1271, when the Great Khan of Mongol, Kublai Khan, one of the grandsons of Genghis Khan, assumed the additional title of Emperor of China, and considered his inherited part of the Mongol Empire as a Chinese dynasty. In the preceding decades, the Mongols had conquered the Jin dynasty in Northern China, and the Southern Song dynasty fell in 1279 after a protracted and bloody war. The Mongol Yuan dynasty became the first conquest dynasty in Chinese history to rule the entire China proper and its population as an ethnic minority. The dynasty also directly controlled the Mongol heartland and other regions, inheriting the largest share of territory of the eastern Mongol empire, which roughly coincided with the modern area of China and nearby regions in East Asia. Further expansion of the empire was halted after defeats in the invasions of Japan and Vietnam. Following the previous Jin dynasty, the capital of Yuan dynasty was established at Khanbaliq (also known as Dadu, modern-day Beijing). The Grand Canal was reconstructed to connect the remote capital city to lively economic hubs in southern part of China, setting the precedence and foundation for Beijing to largely remain as the capital of the successive regimes of the unified Chinese mainland.

A series of Mongol civil wars in the late 13th century led to the division of the Mongol Empire. In 1304 the emperors of the Yuan dynasty were upheld as the nominal Khagan over western khanates (the Chagatai Khanate, the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate), which nonetheless remained de facto autonomous. The era was known as Pax Mongolica, when much of the Asian continent was ruled by the Mongols. For the first and only time in history, the Silk Road was controlled entirely by a single state, facilitating the flow of people, trade, and cultural exchange. A network of roads and a postal system were established to connect the vast empire. Lucrative maritime trade, developed from the previous Song dynasty, continued to flourish, with Quanzhou and Hangzhou emerging as the largest ports in the world. Adventurous travelers from the far west, most notably the Venetian, Marco Polo, would settle in China for decades. Upon his return, his detail travel record inspired generations of medieval Europeans with the splendors of the far East. The Yuan dynasty was the first ancient economy, where paper currency, known at the time as Jiaochao, was used as the predominant medium of exchange. Its unrestricted issuance in the late Yuan dynasty inflicted hyperinflation, which eventually brought the downfall of the dynasty.

While the Mongol rulers of the Yuan dynasty adopted substantially to Chinese culture, their sinicization was of lesser extent compared to earlier conquest dynasties in Chinese history. For preserving racial superiority as the conqueror and ruling class, traditional nomadic customs and heritage from the Mongolian Steppe were held in high regard. On the other hand, the Mongol rulers also adopted flexibly to a variety of cultures from many advanced civilizations within the vast empire. Traditional social structure and culture in China underwent immense transform during the Mongol dominance. Large groups of foreign migrants settled in China, who enjoyed elevated social status over the majority Han Chinese, while enriching Chinese culture with foreign elements. The class of scholar officials and intellectuals, traditional bearers of elite Chinese culture, lost substantial social status. This stimulated the development of culture of the common folks. There were prolific works in zaju variety shows and literary songs (sanqu), which were written in a distinctive poetry style known as qu. Novels of vernacular style gained unprecedented status and popularity.

Before the Mongol invasion, Chinese dynasties reported approximately 120 million inhabitants; after the conquest had been completed in 1279, the 1300 census reported roughly 60 million people.[73] This major decline is not necessarily due only to Mongol killings. Scholars such as Frederick W. Mote argue that the wide drop in numbers reflects an administrative failure to record rather than an actual decrease; others such as Timothy Brook argue that the Mongols created a system of enserfment among a huge portion of the Chinese populace, causing many to disappear from the census altogether; other historians including William McNeill and David Morgan consider that plague was the main factor behind the demographic decline during this period. In the 14th century China suffered additional depredations from epidemics of plague, estimated to have killed around a quarter of the population of China.[74]: 348–351

Throughout the Yuan dynasty, there was some general sentiment among the populace against the Mongol dominance. Yet rather than the nationalist cause, it was mainly strings of natural disasters and incompetent, corrupt governance that triggered widespread peasant uprisings since the 1340s. After the massive naval engagement at Lake Poyang, Zhu Yuanzhang prevailed over other rebel forces in the south. He proclaimed himself emperor and founded the Ming dynasty in 1368. The same year his northern expedition army captured the capital Khanbaliq. The Yuan remnants fled back to Mongolia and sustained the regime, but the period of Yuan dominance was effectively over for good. Other Mongol Khanates in Central Asia continued to exist after the fall of Yuan dynasty in China.

Ming dynasty (1368–1644)

The Ming dynasty was founded by Zhu Yuanzhang in 1368, who proclaimed himself as the Hongwu Emperor. The capital was initially set at Nanjing, and was later moved to Beijing from Yongle Emperor's reign onward.

Urbanization increased as the population grew and as the division of labor grew more complex. Large urban centers, such as Nanjing and Beijing, also contributed to the growth of private industry. In particular, small-scale industries grew up, often specializing in paper, silk, cotton, and porcelain goods. For the most part, however, relatively small urban centers with markets proliferated around the country. Town markets mainly traded food, with some necessary manufactures such as pins or oil.

Despite the xenophobia and intellectual introspection characteristic of the increasingly popular new school of neo-Confucianism, China under the early Ming dynasty was not isolated. Foreign trade and other contacts with the outside world, particularly Japan, increased considerably. Chinese merchants explored all of the Indian Ocean, reaching East Africa with the voyages of Zheng He.

The Hongwu Emperor, being the only founder of a Chinese dynasty who was also of peasant origin, had laid the foundation of a state that relied fundamentally in agriculture. Commerce and trade, which flourished in the previous Song and Yuan dynasties, were less emphasized. Neo-feudal landholdings of the Song and Mongol periods were expropriated by the Ming rulers. Land estates were confiscated by the government, fragmented, and rented out. Private slavery was forbidden. Consequently, after the death of the Yongle Emperor, independent peasant landholders predominated in Chinese agriculture. These laws might have paved the way to removing the worst of the poverty during the previous regimes. Towards later era of the Ming dynasty, with declining government control, commerce, trade and private industries revived.

The dynasty had a strong and complex central government that unified and controlled the empire. The emperor's role became more autocratic, although Hongwu Emperor necessarily continued to use what he called the "Grand Secretariat" to assist with the immense paperwork of the bureaucracy, including memorials (petitions and recommendations to the throne), imperial edicts in reply, reports of various kinds, and tax records. It was this same bureaucracy that later prevented the Ming government from being able to adapt to changes in society, and eventually led to its decline.

The Yongle Emperor strenuously tried to extend China's influence beyond its borders by demanding other rulers send ambassadors to China to present tribute. A large navy was built, including four-masted ships displacing 1,500 tons. A standing army of 1 million troops was created. The Chinese armies conquered and occupied Vietnam for around 20 years, while the Chinese fleet sailed the China seas and the Indian Ocean, cruising as far as the east coast of Africa. The Chinese gained influence in eastern Moghulistan. Several maritime Asian nations sent envoys with tribute for the Chinese emperor. Domestically, the Grand Canal was expanded and became a stimulus to domestic trade. Over 100,000 tons of iron per year were produced. Many books were printed using movable type. The imperial palace in Beijing's Forbidden City reached its current splendor. It was also during these centuries that the potential of south China came to be fully exploited. New crops were widely cultivated and industries such as those producing porcelain and textiles flourished.

In 1449 Esen Tayisi led an Oirat Mongol invasion of northern China which culminated in the capture of the Zhengtong Emperor at Tumu. Since then, the Ming became on the defensive on the northern frontier, which led to the Ming Great Wall being built. Most of what remains of the Great Wall of China today was either built or repaired by the Ming. The brick and granite work was enlarged, the watchtowers were redesigned, and cannons were placed along its length.

At sea the Ming became increasingly isolationist after the death of the Yongle Emperor. The treasure voyages which sailed the Indian Ocean were discontinued, and the maritime prohibition laws were set in place banning the Chinese from sailing abroad. European traders who reached China in the midst of the Age of Discovery were repeatedly rebuked in their requests for trade, with the Portuguese being repulsed by the Ming navy at Tuen Mun in 1521 and again in 1522. Domestic and foreign demands for overseas trade, deemed illegal by the state, led to widespread wokou piracy attacking the southeastern coastline during the rule of the Jiajing Emperor (1507–1567), which only subsided after the opening of ports in Guangdong and Fujian and much military suppression.[75] In addition to raids from Japan by the wokou, raids from Taiwan and the Philippines by the Pisheye also ravaged the southern coasts.[76] The Portuguese were allowed to settle in Macau in 1557 for trade, which remained in Portuguese hands until 1999. After the Spanish invasion of the Philippines, trade with the Spanish at Manila imported large quantities of Mexican and Peruvian silver from the Spanish Americas to China.[77]: 144–145 The Dutch entry into the Chinese seas was also met with fierce resistance, with the Dutch being chased off the Penghu islands in the Sino-Dutch conflicts of 1622–1624 and were forced to settle in Taiwan instead. The Dutch in Taiwan fought with the Ming in the Battle of Liaoluo Bay in 1633 and lost, and eventually surrendered to the Ming loyalist Koxinga in 1662, after the fall of the Ming dynasty.

In 1556, during the rule of the Jiajing Emperor, the Shaanxi earthquake killed about 830,000 people, the deadliest earthquake of all time.

The Ming dynasty intervened deeply in the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), which ended with the withdrawal of all invading Japanese forces in Korea, and the restoration of the Joseon dynasty, its traditional ally and tributary state. The regional hegemony of the Ming dynasty was preserved at a toll on its resources. Coincidentally, with Ming's control in Manchuria in decline, the Manchu (Jurchen) tribes, under their chieftain Nurhaci, broke away from Ming's rule, and emerged as a powerful, unified state, which was later proclaimed as the Qing dynasty. It went on to subdue the much weakened Korea as its tributary, conquered Mongolia, and expanded its territory to the outskirt of the Great Wall. The most elite army of the Ming dynasty was to station at the Shanhai Pass to guard the last stronghold against the Manchus, which weakened its suppression of internal peasants uprisings.

Qing dynasty (1644–1912)

The Qing dynasty (1644–1912) was the last imperial dynasty in China. Founded by the Manchus, it was the second conquest dynasty to rule the entirety of China proper, and roughly doubled the territory controlled by the Ming. The Manchus were formerly known as Jurchens, residing in the northeastern part of the Ming territory outside the Great Wall. They emerged as the major threat to the late Ming dynasty after Nurhaci united all Jurchen tribes and his son, Hong Taiji, declared the founding of the Qing dynasty in 1636. The Qing dynasty set up the Eight Banners system that provided the basic framework for the Qing military conquest. Li Zicheng's peasant rebellion captured Beijing in 1644 and the Chongzhen Emperor, the last Ming emperor, committed suicide. The Manchus allied with the Ming general Wu Sangui to seize Beijing, which was made the capital of the Qing dynasty, and then proceeded to subdue the Ming remnants in the south. During the Ming-Qing transition, when the Ming dynasty and later the Southern Ming, the emerging Qing dynasty, and several other factions like the Shun dynasty and Xi dynasty founded by peasant revolt leaders fought against each another, which, along with innumerable natural disasters at that time such as those caused by the Little Ice Age[78] and epidemics like the Great Plague during the last decade of the Ming dynasty,[79] caused enormous loss of lives and significant harm to the economy. In total, these decades saw the loss of as many as 25 million lives, but the Qing appeared to have restored China's imperial power and inaugurate another flowering of the arts.[80] The early Manchu emperors combined traditions of Inner Asian rule with Confucian norms of traditional Chinese government and were considered a Chinese dynasty.

The Manchus enforced a 'queue order', forcing Han Chinese men to adopt the Manchu queue hairstyle. Officials were required to wear Manchu-style clothing Changshan (bannermen dress and Tangzhuang), but ordinary Han civilians were allowed to wear traditional Han clothing. Bannermen could not undertake trade or manual labor; they had to petition to be removed from banner status. They were considered aristocracy and were given annual pensions, land, and allotments of cloth. The Kangxi Emperor ordered the creation of the Kangxi Dictionary, the most complete dictionary of Chinese characters that had been compiled.

Over the next half-century, all areas previously under the Ming dynasty were consolidated under the Qing. Conquests in Central Asia in the eighteenth century extended territorial control. Between 1673 and 1681, the Kangxi Emperor suppressed the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, an uprising of three generals in Southern China who had been denied hereditary rule of large fiefdoms granted by the previous emperor. In 1683, the Qing staged an amphibious assault on southern Taiwan, bringing down the rebel Kingdom of Tungning, which was founded by the Ming loyalist Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong) in 1662 after the fall of the Southern Ming, and had served as a base for continued Ming resistance in Southern China. The Qing defeated the Russians at Albazin, resulting in the Treaty of Nerchinsk.

By the end of Qianlong Emperor's long reign in 1796, the Qing Empire was at its zenith. The Qing ruled more than one-third of the world's population, and had the largest economy in the world. By area it was one of the largest empires ever.

In the 19th century the empire was internally restive and externally threatened by western powers. The defeat by the British Empire in the First Opium War (1840) led to the Treaty of Nanking (1842), under which Hong Kong was ceded to Britain and importation of opium (produced by British Empire territories) was allowed. Opium usage continued to grow in China, adversely affecting societal stability. Subsequent military defeats and unequal treaties with other western powers continued even after the fall of the Qing dynasty.

Internally the Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864), a Christian religious movement led by the "Heavenly King" Hong Xiuquan swept from the south to establish the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom and controlled roughly a third of China proper for over a decade. The court in desperation empowered Han Chinese officials such as Zeng Guofan to raise local armies. After initial defeats, Zeng crushed the rebels in the Third Battle of Nanking in 1864.[81] This was one of the largest wars in the 19th century in troop involvement; there was massive loss of life, with a death toll of about 20 million.[82] A string of civil disturbances followed, including the Punti–Hakka Clan Wars, Nian Rebellion, Dungan Revolt, and Panthay Rebellion.[83] All rebellions were ultimately put down, but at enormous cost and with millions dead, seriously weakening the central imperial authority. China never rebuilt a strong central army, and many local officials used their military power to effectively rule independently in their provinces.[81]

Yet the dynasty appeared to recover in the Tongzhi Restoration (1860–1872), led by Manchu royal family reformers and Han Chinese officials such as Zeng Guofan and his proteges Li Hongzhang and Zuo Zongtang. Their Self-Strengthening Movement made effective institutional reforms, imported Western factories and communications technology, with prime emphasis on strengthening the military. However, the reform was undermined by official rivalries, cynicism, and quarrels within the imperial family. The defeat of Yuan Shikai's modernized "Beiyang Fleet" in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) led to the formation of the New Army. The Guangxu Emperor, advised by Kang Youwei, then launched a comprehensive reform effort, the Hundred Days' Reform (1898). Empress Dowager Cixi, however, feared that precipitous change would lead to bureaucratic opposition and foreign intervention and quickly suppressed it.

In the summer of 1900, the Boxer Uprising opposed foreign influence and murdered Chinese Christians and foreign missionaries. When Boxers entered Beijing, the Qing government ordered all foreigners to leave, but they and many Chinese Christians were besieged in the foreign legations quarter. An Eight-Nation Alliance sent the Seymour Expedition of Japanese, Russian, British, Italian, German, French, American, and Austrian troops to relieve the siege, but they were routed and forced to retreat by Boxer and Qing troops at the Battle of Langfang. After the Alliance's attack on the Dagu Forts, the court declared war on the Alliance and authorised the Boxers to join with imperial armies. After fierce fighting at Tianjin, the Alliance formed the second, much larger Gaselee Expedition and finally reached Beijing; the Empress Dowager evacuated to Xi'an. The Boxer Protocol ended the war, exacting a tremendous indemnity.

The Qing court then instituted administrative and legal reforms known as the late Qing reforms, including abolition of the examination system. But young officials, military officers, and students debated reform, perhaps a constitutional monarchy, or the overthrow of the dynasty and the creation of a republic. They were inspired by an emerging public opinion formed by intellectuals such as Liang Qichao and the revolutionary ideas of Sun Yat-sen. A localised military uprising, the Wuchang uprising, began on 10 October 1911, in Wuchang (today part of Wuhan), and soon spread. The Republic of China was proclaimed on 1 January 1912, ending 2,000 years of dynastic rule.

Modern China

Republic of China (since 1912)

The provisional government of the Republic of China was formed in Nanjing on 12 March 1912. Sun Yat-sen became President of the Republic of China, but he turned power over to Yuan Shikai, who commanded the New Army. Over the next few years, Yuan proceeded to abolish the national and provincial assemblies, and declared himself as the emperor of Empire of China in late 1915, in the style of an absolute monarchy. Yuan's imperial ambitions were fiercely opposed by his subordinates; faced with the rapidly growing prospect of violent rebellion, he abdicated in March 1916 and died of natural causes in June.

Yuan's death in 1916 left a power vacuum; the republican government(that had been nearly brought to its knees by his policies) was all but shattered. This opened the way for the Warlord Era, during which much of China was ruled by shifting coalitions of competing provincial military leaders and the Beiyang government, ushering in a short-lived period of uncertainty. Intellectuals, disappointed in the failure of the Republic, launched the New Culture Movement.

In 1919, the May Fourth Movement began as a response to the pro-Japanese terms imposed on China by the Treaty of Versailles following World War I. It quickly became a nationwide protest movement. The protests were a moral success as the cabinet fell and China refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles, which had awarded German holdings of Shandong to Japan. Memory of the mistreatment at Versailles fuels resentment into the 21st century.[84]

Political and intellectual ferment waxed strong throughout the 1920s and 1930s. According to Patricia Ebrey:

- "Nationalism, patriotism, progress, science, democracy, and freedom were the goals; imperialism, feudalism, warlordism, autocracy, patriarchy, and blind adherence to tradition were the enemies. Intellectuals struggled with how to be strong and modern and yet Chinese, how to preserve China as a political entity in the world of competing nations."[85]

In the 1920s Sun Yat-sen established a revolutionary base in Guangzhou and set out to unite the fragmented nation. He welcomed assistance from the Soviet Union (itself fresh from Lenin's Communist takeover) and he entered into an alliance with the fledgling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). After Sun's death from cancer in 1925, one of his protégés, Chiang Kai-shek, seized control of the Nationalist Party (KMT) and succeeded in bringing most of south and central China under its rule in the Northern Expedition (1926–1927). Having defeated the warlords in the south and central China by military force, Chiang was able to secure the nominal allegiance of the warlords in the North and establish the Nationalist government in Nanjing. In 1927, Chiang turned on the CCP and relentlessly purged the Communists elements in his NRA. In 1934, driven from their mountain bases such as the Chinese Soviet Republic, the CCP forces embarked on the Long March across China's most desolate terrain to the northwest, a feat transformed into legend, where they established a guerrilla base at Yan'an in Shaanxi. During the Long March, the communists reorganised under a new leader, Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung).

The bitter Chinese Civil War between the Nationalists and the Communists continued, openly or clandestinely, through the 14-year-long Japanese occupation of various parts of the country (1931–1945). The two Chinese parties nominally formed a United Front to oppose the Japanese in 1937, during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), which became a part of World War II, although this alliance was tenuous at best and disagreements, sometimes violent, between the forces were still common. Japanese forces committed numerous war atrocities against the civilian population, including biological warfare (see Unit 731) and the Three Alls Policy (Sankō Sakusen), namely being: "Kill All, Burn All and Loot All".[86] During the war, China was recognized as one of the Allied "Big Four" in the Declaration by United Nations, as a tribute to its enduring struggle against the invading Japanese.[87] China was one of the four major Allies of World War II, and was later considered one of the primary victors in the war.[88]

Following the defeat of Japan in 1945, the war between the Nationalist government forces and the CCP resumed, after failed attempts at reconciliation and a negotiated settlement. By 1949, the CCP had established control over most of the country. Odd Arne Westad says the Communists won the Civil War because they made fewer military mistakes than Chiang, and because in his search for a powerful centralized government, Chiang antagonised too many interest groups in China. Furthermore, his party was weakened in the war against the Japanese. Meanwhile, the Communists told different groups, such as peasants, exactly what they wanted to hear, and cloaked themselves in the cover of Chinese Nationalism.[89] During the civil war both the Nationalists and Communists carried out mass atrocities, with millions of non-combatants killed by both sides.[90] These included deaths from forced conscription and massacres.[91]

Now, rotten with internal corruption and compounding tactical error after error under crumbling leadership, the Nationalists were slowly routed towards the South. When the Nationalist government forces were defeated by CCP forces in mainland China in 1949, the Nationalist government fled to Taiwan with its forces, along with Chiang and a large number of their supporters; the Nationalist government had taken effective control of Taiwan at the end of WWII as part of the overall Japanese surrender, when Japanese troops in Taiwan surrendered to the Republic of China troops there.[92]

Until the early 1970s the ROC was recognised as the sole legitimate government of China by the United Nations, the United States and most Western nations, refusing to recognise the PRC on account of its status as a communist nation during the Cold War. This changed in 1971 when the PRC was seated in the United Nations, replacing the ROC. The KMT ruled Taiwan under martial law until 1987, with the stated goal of being vigilant against Communist infiltration and preparing to retake mainland China. Therefore, political dissent was not tolerated during that period, and crackdowns against dissidents were common.

In the 1990s the ROC underwent a major democratic reform, beginning with the 1991 resignation of the members of the Legislative Yuan and National Assembly elected in 1947. These groups were originally created to represent mainland China constituencies. Also lifted were the restrictions on the use of Taiwanese languages in the broadcast media and in schools. This culminated with the first direct presidential election in 1996 against the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) candidate and former dissident, Peng Ming-min. In 2000, the KMT status as the ruling party ended when the DPP took power, only to regain its status in the 2008 election by Ma Ying-jeou.

Due to the controversial nature of Taiwan's political status, the ROC is currently recognised by merely 12 UN member states and the Holy See as of 2024 as the legitimate government of "China".

People's Republic of China (since 1949)

Major combat in the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949 with the KMT pulling out of the mainland, with the government relocating to Taipei and maintaining control only over a few islands. The CCP was left in control of mainland China. On 1 October 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic of China.[93] "Communist China" and "Red China" were two common names for the PRC.[94]

The PRC was shaped by a series of campaigns and five-year plans. The Great Leap Forward, a radical campaign that encompassed numerous attempted economic and social reforms, resulted in tens of millions of deaths.[95][better source needed] Mao's government carried out mass executions of landowners, instituted collectivisation and implemented the Laogai camp system. Execution, deaths from forced labor and other atrocities resulted in millions of deaths under Mao. In 1966 Mao and his allies launched the Cultural Revolution, which continued until Mao's death a decade later. The Cultural Revolution, motivated by power struggles within the Party and a fear of the Soviet Union, led to a major upheaval in Chinese society.

Following the Sino-Soviet split and motivated by concerns of invasion by either the Soviet Union or the United States, China initiated the Third Front campaign to develop national defense and industrial infrastructure in its rugged interior.[96]: 44 Through its distribution of infrastructure, industry, and human capital around the country, the Third Front created favorable conditions for subsequent market development and private enterprise.[96]: 177

In 1972, at the peak of the Sino-Soviet split, Mao and Zhou Enlai met U.S. president Richard Nixon in Beijing to establish relations with the US. In the same year, the PRC was admitted to the United Nations in place of the Republic of China, with permanent membership of the Security Council.

A power struggle followed Mao's death in 1976. The Gang of Four were arrested and blamed for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution, marking the end of a turbulent political era in China. Deng Xiaoping outmaneuvered Mao's anointed successor chairman Hua Guofeng, and gradually emerged as the de facto leader over the next few years.

Deng Xiaoping was the Paramount Leader of China from 1978 to 1992, although he never became the head of the party or state, and his influence within the Party led the country to significant economic reforms. The CCP subsequently loosened governmental control over citizens' personal lives and the communes were disbanded with many peasants receiving multiple land leases, which greatly increased incentives and agricultural production. In addition, there were many free market areas opened. The most successful free market area was Shenzhen. It is located in Guangdong and the property tax free area still exists today. This turn of events marked China's transition from a planned economy to a mixed economy with an increasingly open market environment, a system termed by some[97] as market socialism, and officially by the CCP as Socialism with Chinese characteristics. The PRC adopted its current constitution on 4 December 1982.

In 1989 the death of former general secretary Hu Yaobang helped to spark the Tiananmen Square protests of that year, during which students and others campaigned for several months, speaking out against corruption and in favour of greater political reform, including democratic rights and freedom of speech. However, they were eventually put down on 4 June when Army troops and vehicles entered and forcibly cleared the square, resulting in considerable numbers of fatalities. This event was widely reported, and brought worldwide condemnation and sanctions against the communist government.[98][99]

CCP general secretary and PRC president Jiang Zemin and PRC premier Zhu Rongji, both former mayors of Shanghai, led post-Tiananmen PRC in the 1990s. Under Jiang and Zhu's ten years of administration, the PRC's economic performance pulled an estimated 150 million peasants out of poverty and sustained an average annual gross domestic product growth rate of 11.2%.[100][better source needed] The country formally joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. By 1997 and 1999, former European colonies of British Hong Kong and Portuguese Macau became the Hong Kong and Macau special administrative regions of the People's Republic of China, respectively.