Haredi Judaism

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

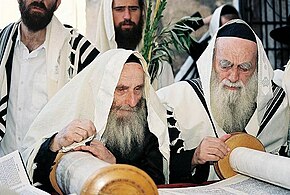

Haredi Judaism (Hebrew: יהדות חֲרֵדִית, romanized: Yahadut Ḥaredit, IPA: [ħaʁeˈdi]; plural Haredim) is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that is characterized by its strict interpretation of religious sources and its accepted halakha (Jewish law) and traditions, in opposition to more accommodating or modern values and practices. Its members are usually referred to as ultra-Orthodox in English; however, the term "ultra-Orthodox" is considered pejorative by many of its adherents, who prefer terms like strictly Orthodox or Haredi. Haredi Jews regard themselves as the most religiously authentic group of Jews but all other Jewish sects strongly disagree and denounce their extreme viewpoints and actions. Haredim regard themselves as the most authentic custodians of Jewish religious law and tradition which, in their opinion, is binding and unchangeable. They consider all other expressions of Judaism, including Modern Orthodoxy, as deviations from God's laws, although other movements of Judaism would disagree.[1]

Some scholars have suggested that Haredi Judaism is a reaction to societal changes, including political emancipation, the Haskalah movement derived from the Enlightenment, acculturation, secularization, religious reform in all its forms from mild to extreme, and the rise of the Jewish national movement. In contrast to Modern Orthodox Judaism, followers of Haredi Judaism segregate themselves from other parts of society, although some Haredi communities encourage young people to get a professional degree or establish a business. Furthermore, some Orthodox groups, like Chabad-Lubavitch, encourage outreach to less observant and unaffiliated Jews and hilonim (secular Israeli Jews). Thus, professional and social relationships often do not form between Haredi and non-Haredi Jews due to the stark contrast of their beliefs.

Haredi communities are found primarily in Israel (17% of Israeli Jews and 13.6% of the total population), North America (12% of American Jews), and Western Europe (most notably Antwerp and Stamford Hill in London). Their estimated global population numbers 2.1 million as of 2020, and, due to a virtual absence of interfaith marriage and a high birth rate, the Haredi population is growing rapidly. For example, 61% of all Jewish children living in the eight-county[a] New York City metropolitan area are Orthodox, with Haredim making up 49% as of 2011.[2] Their numbers have been further boosted since the 1970s by secular Jews adopting a Haredi lifestyle as part of the baal teshuva movement; however, this has been somewhat offset by those leaving.

Terminology

[edit]

The term Haredi is a Modern Hebrew adjective derived from the Biblical verb hared, which appears in the Book of Isaiah (66:2; its plural haredim appears in Isaiah 66:5)[3] and is translated as "[one who] trembles" at the word of God. The word connotes an awe-inspired fear to perform the will of God;[4] it is used to distinguish them from other Orthodox Jews (similar to the names used by Christian Quakers and Shakers to describe their relationship to God).[3][5][6][7]

The term most commonly used by outsiders, for example most American news organizations, is ultra-Orthodox Judaism.[8] Hillel Halkin suggests the origins of the term may date to the 1950s, a period in which Haredi survivors of the Holocaust first began arriving in America.[9] However, Isaac Leeser (1806–1868) was described in 1916 as "ultra-Orthodox".[10]

The word Haredi is often used in the Jewish diaspora in place of the term ultra-Orthodox, which many view as inaccurate or offensive,[11][12][13] it being seen as a derogatory term suggesting extremism;[14] English-language alternatives that have been proposed include fervently Orthodox,[15] strictly Orthodox,[12][16] or traditional Orthodox.[17] Others, however, dispute the characterization of the term as pejorative.[9] Ari L. Goldman, a professor at Columbia University, notes that the term simply serves a practical purpose to distinguish a specific part of the Orthodox community, and is not meant as pejorative.[17] Others, such as Samuel Heilman, criticized terms such as ultra-Orthodox and traditional Orthodox, arguing that they misidentify Haredi Jews as more authentically Orthodox than others, as opposed to adopting customs and practises that reflect their desire to separate from the outside world.[18][9]

The community has sometimes been characterized as traditional Orthodox, in contradistinction to the Modern Orthodox, the other major branch of Orthodox Judaism, and not to be confused with the movement represented by the Union for Traditional Judaism, which originated in Conservative Judaism.[19][20]

Haredi Jews also use other terms to refer to themselves. Common Yiddish words include Yidn (Jews), erlekhe Yidn (virtuous Jews),[11] ben Torah (son of the Torah),[3] frum (pious), and heimish (home-like; i.e., "our crowd").

In Israel, Haredi Jews are sometimes also called by the derogatory slang words dos (plural dosim), that mimics the traditional Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation of the Hebrew word datiyim (religious),[21] and more rarely, sh'chorim (blacks), a reference to the black clothes they typically wear;[22] a related informal term used in English is black hat.[23]

History

[edit]

Throughout Jewish history, Judaism has always faced internal and external challenges to its beliefs and practices which have emerged over time and produced counter-responses. According to its adherents, Haredi Judaism is a continuation of Rabbinic Judaism, and the immediate forebears of contemporary Haredi Jews were the Jewish religious traditionalists of Central and Eastern Europe who fought against secular modernization's influence which reduced Jewish religious observance.[24] Indeed, adherents of Haredi Judaism, just like Rabbinic Jews, see their beliefs as part of an unbroken tradition which dates back to the revelation at Sinai.[25] However, most historians of Orthodoxy consider Haredi Judaism, in its most modern incarnation, to date back to the beginning of the 20th century.[25][26][27]

For centuries, before Jewish emancipation, European Jews were forced to live in ghettos where Jewish culture and religious observance were preserved. Change began in the wake of the Age of Enlightenment, when some European liberals sought to include the Jewish population in the emerging empires and nation states. The influence of the Haskalah movement[28] (Jewish Enlightenment) was also evident. Supporters of the Haskalah held that Judaism must change, in keeping with the social changes around them. Other Jews insisted on strict adherence to halakha (Jewish law and custom).[29][30]

In Germany, the opponents of Reform rallied to Samson Raphael Hirsch, who led a secession from German Jewish communal organizations to form a strictly Orthodox movement, with its own network of synagogues and religious schools. His approach was to accept the tools of modern scholarship and apply them in defence of Orthodox Judaism. In the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (including areas traditionally considered Lithuanian), Jews true to traditional values gathered under the banner of Agudas Shlumei Emunei Yisroel.[31]

Moses Sofer was opposed to any philosophical, social, or practical change to customary Orthodox practice. Thus, he did not allow any secular studies to be added to the curriculum of his Pressburg Yeshiva. Sofer's student Moshe Schick, together with Sofer's sons Shimon and Samuel Benjamin, took an active role in arguing against the Reform movement. Others, such as Hillel Lichtenstein, advocated an even more stringent position for Orthodoxy.

A major historic event was the meltdown after the Universal Israelite Congress of 1868–1869 in Pest. In an attempt to unify all streams of Judaism under one constitution, the Orthodox offered the Shulchan Aruch as the ruling Code of law and observance. This was dismissed by the reformists, leading many Orthodox rabbis to resign from the Congress and form their own social and political groups. Hungarian Jewry split into two major institutionally sectarian groups: Orthodox, and Neolog. However, some communities refused to join either of the groups, calling themselves "Status Quo".[citation needed]

Schick demonstrated support in 1877 for the separatist policies of Samson Raphael Hirsch in Germany. Schick's own son was enrolled in the Hildesheimer Rabbinical Seminary, headed by Azriel Hildesheimer, which taught secular studies. Hirsch, however, did not reciprocate, and expressed astonishment at Schick's halakhic contortions in condemning even those Status Quo communities that clearly adhered to halakha.[32] Lichtenstein opposed Hildesheimer, and his son Hirsh Hildesheimer, as they made use of the German language in sermons from the pulpit and seemed to lean in the direction of Zionism.[33]

Shimon Sofer was somewhat more lenient than Lichtenstein on the use of German in sermons, allowing the practice as needed for the sake of keeping cordial relations with the various governments. Likewise, he allowed extra-curricular studies of the gymnasium for students whose rabbinical positions would be recognized by the governments, stipulating the necessity to prove the strict adherence to the God-fearing standards per individual case.[34]

In 1912, the World Agudath Israel was founded, to differentiate itself from the Torah Nationalist Mizrachi and secular Zionist organizations. It was dominated by the Hasidic rebbes and Lithuanian rabbis and roshei yeshiva (deans). The organization nominated rabbis who subsequently were elected as representatives in the Polish legislature Sejm, such as Meir Shapiro and Yitzhak-Meir Levin. Not all Hasidic factions joined the Agudath Israel, remaining independent instead, such as Machzikei Hadat of Galicia.[35]

In 1919, Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld and Yitzchok Yerucham Diskin founded the Edah HaChareidis as part of Agudath Israel in then-Mandate Palestine.

In 1924, Agudath Israel obtained 75 percent of the votes in the Kehilla elections.[36]

The Orthodox community polled some 16,000 of a total 90,000 at the Knesseth Israel in 1929.[37] But Sonnenfeld lobbied Sir John Chancellor, the High Commissioner, for separate representation in the Palestine Communities Ordinance from that of the Knesseth Israel. He explained that the Agudas Israel community would cooperate with the Vaad Leumi and the National Jewish Council in matters pertaining to the municipality, but sought to protect its religious convictions independently. The community petitioned the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations on this issue. The one community principle was victorious, despite their opposition, but this is seen as the creation of the Haredi community in Israel, separate from the other Orthodox and Zionist movements.[38]

In 1932, Sonnenfeld was succeeded by Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky, a disciple of the Shevet Sofer, one of the grandchildren of Moses Sofer. Dushinsky promised to build up a strong Jewish Orthodoxy at peace with the other Jewish communities and the non-Jews.[39]

Post-Holocaust

[edit]In general, the present-day Haredi population originate from two distinct post-Holocaust waves:

- The vast majority of Hasidic and Litvak communities were destroyed during the Holocaust.[40][41] Although Hasidic customs have largely been preserved, the customs of Lithuanian Jewry, including its unique Hebrew pronunciation, have been almost lost. Litvish customs are still preserved primarily by the few older Jews who were born in Lithuania prior to the Holocaust. In the decade or so after 1945, there was a strong drive to revive and maintain these lifestyles by some notable Haredi leaders.

- The Chazon Ish was particularly prominent in the early days of the State of Israel. Aharon Kotler established many of the Haredi schools and yeshivas in the United States and Israel; and Joel Teitelbaum had a significant impact on revitalizing Hasidic Jewry, as well as many of the Jews who fled Hungary during the 1956 revolution who became followers of his Satmar dynasty, and became the largest Hasidic group in the world. These Jews typically have maintained a connection only with other religious family members. As such, those growing up in such families have little or no contact with non-Haredi Jews.[42][43]

- The second wave began in the 1970s associated with the religious revival of the so-called baal teshuva movement,[44][45][46][47] although most of the newly religious become Orthodox, and not necessarily fully Haredi.[citation needed] The formation and spread of the Sephardic Haredi lifestyle movement also began in the 1980s by Ovadia Yosef, alongside the establishment of the Shas party in 1984. This led many Sephardi Jews to adopt the clothing and culture of the Lithuanian Haredi Judaism, though it had no historical basis in their own tradition.[citation needed] Many yeshivas were also established specifically for new adopters of the Haredi way of life.[citation needed]

The original Haredi population has been instrumental in the expansion of their lifestyle, though criticisms have been made of discrimination towards the later adopters of the Haredi lifestyle in shidduchim (matchmaking)[48] and the school system.[49]

Practices and beliefs

[edit]The Haredim represent the conservative or pietistic form of Jewish fundamentalism, distinct from the radical fundamentalism of Gush Emunim,[50] and emphasising withdrawal from, and disdain for, the secular world, and the creation of an alternative world which insulates the Torah and the life it prescribes from outside influences.[51] Haredi Judaism is not an institutionally cohesive or homogeneous group, but comprises a diversity of spiritual and cultural orientations, generally divided into a broad range of Hasidic courts and Litvishe-Yeshivish streams from Eastern Europe, and Oriental Sephardic Haredi Jews. These groups often differ significantly from one another in their specific ideologies and lifestyles, as well as the degree of stringency in religious practice, rigidity of religious philosophy, and isolation from the general culture that they maintain.[citation needed] Some Haredis encourage outreach to less observant and unaffiliated Jews and hilonim (secular Israeli Jews).[52]

Some scholars, including some secular and Reform Jews, describe the Haredim as "radical fundamentalists".[53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60]

Efforts to keep clear of external influence is a core characteristic of Haredi Judaism. Historically, new mediums of communication such as books, newspapers and magazines, and later tapes, CDs and television, were dealt with by either transforming and controlling the content, or choosing to have rabbinic leadership censor it selectively or altogether. In the modern digital era, difficulty in censoring the Internet and conversely, the Internet's importance, resulted in a decades long and ongoing struggle of comprehension, adaption, and regulation on the part of rabbinical leadership and community activists.[61]

These beliefs and practices, which have been interpreted as "isolationist", can bring them into conflict with authorities. In 2018, a Haredi school in the United Kingdom was rated as "inadequate" by the Office for Standards in Education, after repeated complaints were raised about the censoring of textbooks and exam papers which contained mentions of homosexuality, examples of women socializing with men, pictures showing women's shoulders and legs, or information that contradicts a creationist worldview.[62][63]

Lifestyle and family

[edit]

Haredi life, like Orthodox Jewish life in general, is very family-centered and ordered. Boys and girls attend separate schools, and proceed to higher Torah study, in a yeshiva or seminary, respectively, starting anywhere between the ages of 13 and 18. A significant proportion of young men remain in yeshiva until their marriage (often arranged through arranged marriage). After marriage, many Haredi men continue their Torah studies in a kollel.

Studying in secular institutions is often discouraged, although educational facilities for vocational training in a Haredi framework do exist. In the United States and Europe, the majority of Haredi males are active in the workforce. For various reasons, in Israel, most (56%) of their male members do work, though some of those are part of the unofficial workforce.[64][65][66][67] Haredi families (and Orthodox Jewish families in general) are usually much larger than non-Orthodox Jewish families, with as many as twelve or more children.[43] About 70% of female Haredi Jews in Israel work.[64]

Haredi Jews are typically opposed to the viewing of television and films,[68] and the reading of secular newspapers and books. There has been a strong campaign against the Internet, and Internet-enabled mobile phones without filters have also been banned by leading rabbis.[69][70][71] In May 2012, 40,000 Haredim gathered at Citi Field, a baseball park in New York City, to discuss the dangers of unfiltered Internet.[70][72] The event was organized by the Ichud HaKehillos LeTohar HaMachane. The Internet has been allowed for business purposes so long as filters are installed.

In some instances, forms of recreation which conform to Jewish law are treated as antithetical to Haredi Judaism. In 2013, the Rabbinical Court of the Ashkenazi Community in the Haredi settlement of Beitar Illit ruled against Zumba (a type of dance fitness) classes, although they were held with a female instructor and all-female participants.[73][74] The Court said in part: "Both in form and manner, the activity [Zumba] is entirely at odds with both the ways of the Torah and the holiness of Israel, as are the songs associated to it."[74]

Shidduch ("Matchmaking")

[edit]With Haredi Judaism having a heavy emphasis on marriage — especially while young — some members rely on the shidduch (matchmaking) system. They employ a schadhan (a professional matchmaker) to support them in their search for a spouse. While there is no current statistical data showing how many people use the services of a schadhan, it is estimated that the vast majority of Haredi couples were paired by one.[75]

However, with the broader societal shift to online dating, matchmaking in Orthodox and Haredi Judaism has started making inroads online. Vastly different from the most popular online dating services, apps like "Shidduch" pair couples based upon shared values and life goals. To do this, users fill-out a digital resume. The app was made possible by a partnership between its developers and the Orthodox Union — the same group responsible for kosher food certification ("Circle-U").[76]

Dress

[edit]

The standard mode of dress for males of the Lithuanian stream is a black or navy suit and a white shirt.[77] Headgear includes black Fedora or Homburg hats, with black skull caps. Pre-war Lithuanian yeshiva students also wore light coloured suits, along with beige or grey hats,[78] and prior to the 1990s, it was common for Americans of the Lithuanian stream to wear coloured shirts throughout the week, reserving white shirts for Shabbos.[79]

Beards are common among Haredi and many other Orthodox Jewish men, and Hasidic men will almost never be clean-shaven.

Women adhere to the laws of modest dress, and wear long skirts and sleeves, high necklines, and, if married, some form of hair covering.[80] Haredi women never wear trousers, although most do wear pajama-trousers within the home at night.[81]

Over the years, it has become popular among some Haredi women to wear sheitels (wigs), that are thought to be more attractive than their own natural hair (drawing criticism from some more conservative Haredi rabbis). Mainstream Sephardi Haredi rabbi Ovadia Yosef forbade the wearing of wigs altogether.[82] Haredi women often dress more freely and casually within the home, as long as the body remains covered in accordance with the halakha. More modernized Haredi women are somewhat more lenient in matters of their dress, and some follow the latest trends and fashions, while conforming to halakha.[81]

Non-Lithuanian Hasidic men and women differ from the Lithuanian stream by having a much more specific dress code, the most obvious difference for men being the full-length suit jacket (rekel) on weekdays, and the fur hat (shtreimel) and silk caftan (bekishe) on the Sabbath.

Neighborhoods

[edit]Haredi neighborhoods have been said by some to be safer with less violent crime, although this is a generalization with limited evidence and even that applies to only specific communities rather than in general.[83]

In Israel, the entrances to some of the most extreme Haredi neighborhoods are fitted with signs that ask for modest clothing to be worn.[84] Some areas are known to have "modesty patrols",[85] and people dressed in ways perceived as immodest may suffer harassment, and advertisements featuring scantily dressed models may be targeted for vandalism.[86][87] These concerns are also addressed through public lobbying and legal avenues.[88][89]

During the week-long Rio Carnival in Rio de Janeiro, many of the city's 7,000 Orthodox Jews feel compelled to leave the town, due to the immodest exposure of participants.[90] In 2001, Haredi campaigners in Jerusalem succeeded in persuading the Egged bus company to get all their advertisements approved by a special committee.[91] By 2011, Egged had gradually removed all bus adverts that featured women, in response to their continuous defacement. A court order that stated such action was discriminatory led to Egged's decision not to feature people at all (neither male nor female).[92] Depictions of certain other creatures, such as space aliens, were also banned, in order not to offend Haredi sensibilities.[93] Haredi Jews also campaign against other types of advertising that promote activities they deem offensive or inappropriate.[94]

Due to halakha law, i.e. activities that orthodox Jews believe are prohibited on Shabbat, most state-run buses in Israel do not run on Saturdays[95], regardless of whether riders are orthodox or even whether they are Jewish. In a similar vein, Haredi Jews in Israel have demanded that the roads in their neighborhoods be closed on Saturdays, vehicular traffic being viewed as an "intolerable provocation" upon their religious lifestyle (see Driving on Shabbat in Jewish law). In most cases, the authorities granted permission after Haredi petitioning and demonstrations, some of them including fierce clashes between Haredi Jews and secular counter-demonstrators, and violence against police and motorists.[96]

Sex separation

[edit]

While Jewish modesty law requires gender separation under various circumstances, observers have contended that there is a growing trend among some groups of Hasidic Haredi Jews to extend its observance to the public arena.[99]

In the Hasidic village of Kiryas Joel, New York, an entrance sign asks visitors to "maintain sex separation in all public areas", and the bus stops have separate waiting areas for men and women.[100] In New Square, another Hasidic enclave, men and women are expected to walk on opposite sides of the road.[99] In Israel, Jerusalem residents of Mea Shearim were banned from erecting a street barrier dividing men and women during the week-long Sukkot festival's nightly parties;[101][102] and street signs requesting that women avoid certain pavements in Beit Shemesh have been repeatedly removed by the municipality.[103]

Since 1973, buses catering to Haredi Jews running from Rockland County and Brooklyn into Manhattan have had separate areas for men and women, allowing passengers to conduct on-board prayer services.[104] Although the lines are privately operated, they serve the general public, and in 2011, the set-up was challenged on grounds of discrimination, and the arrangement was deemed illegal.[105][106] During 2010–2012, there was much public debate in Israel surrounding the existence of segregated Haredi Mehadrin bus lines (whose policy calls for both men and women to stay in their respective areas: men in the front of the bus,[107] and women in the rear of the bus) following an altercation that occurred after a woman refused to move to the rear of the bus to sit among the women. A subsequent court ruling stated that while voluntary segregation should be allowed, forced separation is unlawful.[108] Israeli national airline El Al has agreed to provide gender-separated flights in consideration of Haredi requirements.[109]

Education in the Haredi community is strictly segregated by sex. Yeshiva education for boys is primarily focused on the study of Jewish scriptures, such as the Torah and Talmud (non-Hasidic yeshivas in the United States teach secular studies in the afternoon); girls obtain studies both in Jewish religious education as well as broader secular subjects.[110]

Newspapers and publications

[edit]

In 1930s Poland, the Agudath Israel movement published its own Yiddish-language paper, Dos Yiddishe Tagblatt. In 1950, the Agudah started printing Hamodia, a Hebrew-language Israeli daily.

Haredi publications tend to shield their readership from objectionable material,[111] and perceive themselves as a "counterculture", desisting from advertising secular entertainment and events.[112] The editorial policy of a Haredi newspaper is determined by a rabbinical board, and every edition is checked by a rabbinical censor.[113] A strict policy of modesty is characteristic of the Haredi press in recent years, and pictures of women are usually not printed.[114] In 2009, the Israeli daily Yated Ne'eman doctored an Israeli cabinet photograph replacing two female ministers with images of men,[115] and in 2013, the Bakehilah magazine pixelated the faces of women appearing in a photograph of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.[116] The mainstream Haredi political Shas party also refrains from publishing female images.[117] Among Haredi publishers which have not adopted this policy is ArtScroll, which does publish pictures of women in their books.[118]

No coverage is given to serious crime, violence, sex, or drugs, and little coverage is given to non-Orthodox streams of Judaism.[119] Inclusion of "immoral" content is avoided, and when publication of such stories is a necessity, they are often written ambiguously.[114] The Haredi press generally takes a non-Zionist stance, and gives more coverage to issues that concern the Haredi community, such as the drafting of girls and yeshiva students into the army, autopsies, and Shabbat observance.[112] In Israel, it portrays the secular world as "spitefully anti-Semitic", and describes secular youth as "mindless, immoral, drugged, and unspeakably lewd".[120][121] Such attacks have led to Haredi editors being warned about libelous provocations.[122]

While the Haredi press is extensive and varied in Israel,[112] only around half the Haredi population reads newspapers. Around 10% read secular newspapers, while 40% do not read any newspaper at all.[123] According to a 2007 survey, 27% read the weekend Friday edition of Hamodia, and 26% the Yated Ne'eman.[124] In 2006, the most-read Haredi magazine in Israel was the Mishpacha weekly, which sold 110,000 copies.[124]

Technology

[edit]Haredi leaders have at times suggested a ban on the internet and any internet-capable device,[125] their reasoning being that the immense amount of information can be corrupting, and the ability to use the internet with no observation from the community can lead to individuation.[126]

Some Haredi businessmen utilize the internet throughout the week, but they still observe Shabbat in every aspect by not accepting or processing orders from Friday evening to Saturday evening.[127] They utilize the internet under strict filters and guidelines. The Kosher cell phone was introduced to the Jewish public with the sole ability to call other phones. It was unable to utilize the internet, text other phones, and had no camera feature. In fact, a kosher phone plan was created, with decreased rates for kosher-to-kosher calls, to encourage community.[128][129]

News hotlines

[edit]News hotlines are an important source of news in the Haredi world. Since many Haredi Jews do not listen to the radio or have access to the internet, even if they read newspapers, they are left with little or no access to breaking news. News hotlines were formed to fill this gap, and many have expanded to additional fields over time.[130][131] Currently, many news lines provide rabbinic lectures, entertainment, business advice, and similar services, in addition to their primary function of reporting the news. Many Hasidic sects maintain their own hotlines, where relevant internal news is reported and the group's perspective can be advocated for. In the Israeli Haredi community, there are dozens of prominent hotlines, in both Yiddish and Hebrew. Some Haredi hotlines have played significant public roles.[132]

In Israel

[edit]Attitudes towards Zionism

[edit]From the founding of Zionism in the 1890s, Haredi Jews leaders voiced objections to its secular orientation.[133][134] After the establishment of the State of Israel, Haredi Jews observed the Israeli Independence Day as a day of mourning and referred to Israeli state-holidays as byimey edeyhem ("idolatrous holidays").[135]

The chief political division among Haredi Jews has been in their approach to the State of Israel. After Israeli independence, different Haredi movements took varying positions on it. Only a minority of Haredi Jews consider themselves to be Zionists. Haredim who do not consider themselves Zionists fall into two-camps: non-Zionist, and anti-Zionist. Non-Zionist Haredim, who comprise the majority, do not object to the State of Israel as an independent Jewish state, and many even consider it to be positive, but they do not believe that it has any religious significance. Anti-Zionist Haredim, who are a minority, but are more publicly visible than the non-Zionist majority, believe that any Jewish independence prior to the coming of the Messiah is a sin.[136][137]

The ideologically non-Zionist United Torah Judaism alliance comprising Agudat Yisrael and Degel HaTorah (and the umbrella organizations World Agudath Israel and Agudath Israel of America) represents a moderate and pragmatic stance of cooperation with the State of Israel, and participation in the political system. UTJ has been a participant in numerous coalition governments, seeking to influence state and society in a more religious direction and maintain welfare and religious funding policies. In general, their position is supportive of Israel.[138]

Haredim who are stridently anti-Zionist are under the umbrella of Edah HaChareidis, who reject participation in politics and state funding of its affiliated institutions, in contradistinction to Agudah-affiliated institutions. Neturei Karta is a very small activist organization of anti-Zionist Haredim, whose controversial activities have been strongly condemned, including by other anti-Zionist Haredim.[139] Haredi support is often required to form coalition governments in the Knesset.

In recent years, some rebbes affiliated with Agudath Israel, such as the Sadigura rebbe Avrohom Yaakov Friedman, have taken more hard-line stances on security, settlements, and disengagement.[140]

Shas represents Sephardi and Mizrahi Haredim, and, while having many points in common with Ashkenazi Haredim, differs from them by its more enthusiastic support for the State of Israel and the IDF. The Sikirim group is anti-Zionist group composed of Haredi Jews is considered a radical organization by Israelis.[141]

Marriage

[edit]The purpose of marriage in the Haredi (and Orthodox) viewpoint is for the purpose of companionship, as well as for the purpose of having children.[142]

There is a high rate of marriage in the Haredi community. 83% are married, compared to the non-Haredi community in Israel of 63%.[143] Marriage is viewed as holy, and as the natural home for a man and a woman to truly love each other.

Divorce

[edit]In 2016, the divorce rate in Israel was 5% among the Haredi population, compared to the general population rate of 14%.[143]

In 2016, Haaretz claimed that divorces among Haredim are increasing in Israel.[144] In 2017, some predominantly Haredi cities reported the highest growth rates in divorce in the Israel, in the context of generally falling rates of divorce, [145] and in 2018, some predominantly Haredi cities reported drops in divorce, in the context of generally rising rates of divorce.[146]

When the divorce is linked to one spouse leaving the community, the one who chooses to leave is often shunned from his or her communities and forced to abandon their children, as most courts prefer keeping children in an established status quo.[144][147][148]

Education

[edit]Haredim primarily educate their children in their own private schools, starting with chederim for pre-school to primary school ages, to yeshivos for boys from secondary school ages, and in seminaries, often called Bais Yaakovs, for girls of secondary school ages. Only Jewish religiously observant students are admitted, and parents must agree to abide by the rules of the school to keep their children enrolled. Yeshivas are headed by rosh yeshivas (deans) and principals. Many Hasidic schools in Israel, Europe, and North America teach little or no secular subjects, while some of the Litvish (Lithuanian style) schools in Israel follow educational policies to the Hasidic school. In the U.S., most teach secular subjects to boys and girls, as part of a dual curriculum of secular subjects (generally called "English") and Torah subjects. Yeshivas teach mostly Talmud and Rabbinic literature, while the girls' schools teach Jewish Law, Midrash, and Tanach (Hebrew Bible).

Between 2007 and 2017, the number of Haredim studying in higher education had risen from 1,000 to 10,800.[149]

In 2007, the Kemach Foundation was established to become an investor in the sector's social and economic development, and provide opportunities for employment. Through the philanthropy of Leo Noé of London, later joined by the Wolfson family of New York and Elie Horn from Brazil, Kemach has facilitated academic and vocational training. With a $22m budget, including government funding, Kemach provides individualized career assessment, academic or vocational scholarships, and job placement for the entire Haredi population in Israel. The Foundation is managed by specialists who, coming from the Haredi sector themselves, are familiar with the community's needs and sensitivities. By April 2014, more than 17,800 Haredim have received the services of Kemach, and more than 7,500 have received, or continue to receive, monthly scholarships to fund their academic or vocational studies. From 500 graduates, the net benefits to the government would be 80.8 million NIS if they work for one year, 572.3 million NIS if they work for 5 years, and 2.8 billion NIS (discounted) if they work for 30 years.[150]

The Council for Higher Education announced in 2012 that it was investing NIS 180 million over the following five years to establish appropriate frameworks for the education of Haredim, focusing on specific professions.[151] The largest Haredi campus in Israel is The Haredi Campus - The Academic College Ono.

Military

[edit]

Upon the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, universal conscription was instituted for all able-bodied Jewish males. However, military-aged Haredi men were exempted from service in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) under the Torato Umanuto arrangement, which officially granted deferred entry into the IDF for yeshiva students, but in practice allowed young Haredi men to serve for a significantly reduced period of time or bypass military service altogether. At that time, the Haredi population was very low and only 400 individuals were affected.[152] However, the Haredi population rapidly grew.[153][154] In 2018, the Israel Democracy Institute estimated that the Haredim comprised 12% of Israel's total population and 15% of its Jewish population.[155] Haredim are also younger than the general population. Their absence from the IDF attracts significant resentment from secular Israelis. The most common criticisms of the exemption policy are:

- The Haredim can work in those 2–3 years of their lives in which they do not serve in the IDF, while most soldiers at the IDF are usually paid around $80–250 a month, in addition to clothing and lodging.[156] All the while, Haredi yeshiva students receive significant monthly funds and payments for their religious studies.[157]

- The Haredim, if they so choose, can study at that time.[158][159]

Over the years, as many as 1,000 Haredi Jews have volunteered to serve in a Haredi Jewish unit of the IDF known as the Netzah Yehuda Battalion, or Nahal Haredi. The vast majority of Haredi men, however, continue to receive deferments from military service.[160] Haredim usually reject the practice of IDF service and contend that:

- A yeshiva student has an important role in protecting the Jewish people because Haredim believe that Torah study brings spiritual protection similar to how a soldier in the IDF brings physical protection. Haredim maintain that each role is important in protecting the Jewish people, and one who is a yeshiva student should not abandon his personal duty in spiritually protecting the Jewish people.[161][162][163][164]

- The Israeli army is not conducive to a Haredi lifestyle. It is regarded as a "state-sponsored quagmire of promiscuity" due to Israel conscripting both men and women, and often grouping them together in military activities.[165] Additionally, the keeping of military procedures makes it difficult to observe the Sabbath and many other Jewish practices.[citation needed]

The Torato Umanuto arrangement was enshrined in the Tal Law that came into force in 2002. The High Court of Justice later ruled that it could not be extended in its current form beyond August 2012. A replacement was expected. The IDF was, however, experiencing a shortage of personnel, and there were pressures to reduce the scope of the Torato Omanuto exemption.[166] In June 2024, the Supreme Court of Israel declared any continued exemption of IDF conscription unlawful and the army began drafting 3,000 Haredi men the following month.[167] In March 2014, Israel's parliament approved legislation to end exemptions from military service for Haredi seminary students. The bill was passed by 65 votes to one, and an amendment allowing civilian national service by 67 to one.[168]

There has been much uproar in Haredi society following actions towards Haredi conscription. While some Haredim see this as a great social and economic opportunity,[169] others (including leading rabbis among them) strongly oppose this move.[170] Among the extreme Haredim, there have been some more severe reactions. Several Haredi leaders have threatened that Haredi populations would leave the country if forced to enlist.[171][172] Others have fueled public incitement against secular and National-Religious Jews, and specifically against politicians Yair Lapid and Naftali Bennett, who support and promote Haredi enlistment.[173][174] Some Haredim have taken to threatening their fellows who agree to enlist,[175][176] to the point of physically attacking some of them.[177][178]

The Shahar program, also known as Shiluv Haredim (Ultra-Orthodox integration), allows Haredi men aged 22 to 26 to serve in the army for about a year and a half. At the beginning of their service, they study mathematics and English, which are often not well covered in Haredi boy schools. The program is partly aimed at encouraging Haredi participation in the workforce after military service. However, not all beneficiaries seem to be Haredim.[179]

Employment

[edit]As of 2013[update], figures from the Central Bureau of Statistics on employment rates place Haredi women at 73%, close to the 80% for the non-Haredi Jewish women's national figure; while the number of working Haredi men has increased to 56%, it is still far below the 90% of non-Haredi Jewish men nationwide.[64] As of 2021[update], most Haredi boys instead go to yeshivas and then continue to study at yeshiva after getting married.[180]

The Trajtenberg Committee, charged in 2011 with drafting proposals for economic and social change, called, among other things, for increasing employment among the Haredi population. Its proposals included encouraging military or national service and offering college prep courses for volunteers, creating more employment centers targeting Haredim and experimental matriculation prep courses after yeshiva hours. The committee also called for increasing the number of Haredi students receiving technical training through the Industry, Trade, and Labor Ministry and forcing Haredi schools to carry out standardized testing, as is done at other public schools.[181] It is estimated that half as many of the Haredi community are in employment as the rest of population. This has led to increasing financial deprivation, and 50% of children within the community live below the poverty line. This puts strain on each family, the community, and often the Israeli economy.

The demographic trend indicates the community will constitute an increasing percentage of the population, and consequently, Israel faces an economic challenge in the years ahead due to fewer people in the labor force. A report commissioned by the Treasury found that the Israeli economy may lose more than six billion shekels annually as a result of low Haredi participation in the workforce.[182] The OECD in a 2010 report stated that, "Haredi families are frequently jobless, or are one-earner families in low-paid employment. Poverty rates are around 60% for Haredim."[183]

As of 2017, according to an Israeli finance ministry study, the Haredi participation rate in the labour force is 51%, compared to 89% for the rest of Israeli Jews.[184]

A 2018 study by Oren Heller, a National Insurance Institute of Israel senior economic researcher, has found that while upper mobility among Haredim is significantly greater than the national average, unlike it, this tends not to translate into significantly higher pay.[185]

Haredi families living in Israel benefited from government-subsidized child care when the father studied Torah and the mother worked at least 24 hours per week. However, after Israeli Finance Minister Avigdor Liberman introduced a new policy in 2021, families in which the father is a full-time yeshiva student are no longer eligible for a daycare subsidy. Under this policy, fathers must also work at least part-time in order for the family to qualify for the subsidy. The move was denounced by Haredi leaders.[186]

Other issues

[edit]

The Haredim in general are materially poorer than most other Israelis, but still represent an important market sector due to their bloc purchasing habits.[187] For this reason, some companies and organizations in Israel refrain from including women or other images deemed immodest in their advertisements to avoid Haredi consumer boycotts.[188][189] More than 50 percent of Haredim live below the poverty line, compared with 15 percent of the rest of the population.[190] Their families are also larger, with Haredi women having an average of 6.7 children, while the average Jewish Israeli woman has 3 children.[191] Families with many children often receive economic support through governmental child allowances, government assistance in housing, as well as specific funds by their own community institutions.[192]

In recent years, there has been a process of reconciliation and an attempt to merge Haredi Jews with Israeli society,[193] although employment discrimination is widespread.[194] Haredi Jews such as satirist Kobi Arieli, publicist Sehara Blau, and politician Israel Eichler write regularly for leading Israeli newspapers.

Another important factor in the reconciliation process has been the activities of ZAKA, a Haredi organization known for providing emergency medical attention at the scene of suicide bombings, and Yad Sarah, the largest national volunteer organization in Israel established in 1977 by former Haredi mayor of Jerusalem, Uri Lupolianski. It is estimated that Yad Sarah saves the country's economy an estimated $320 million in hospital fees and long-term care costs each year.[195][196]

Population

[edit]Due to its imprecise definition, lack of data collection, and rapid change over time, estimates of the global Haredi population are difficult to measure, and may significantly underestimate the true number of Haredim, due to their reluctance to participate in surveys and censuses.[197][198]

In 1992, out of a total of 1,500,000 Orthodox Jews worldwide, about 550,000 were Haredi (half of them in Israel).[199] One estimate given in 2011 stated that there were approximately 1.3 million Haredi Jews globally.[200] Studies have shown a very high growth rate, with a large young population.[201] Haredi population grew to 2.1 million in 2020 and is expected to double by 2040.[202]

The vast majority of Haredi Jews are Ashkenazi. However, some 20% of the Haredi population are thought to belong to the Sephardic Haredi stream. In recent decades, Haredi society has grown due to the addition of a religious population that identifies with the Shas movement. The percentage of people leaving the Haredi population has been estimated between 6% and 18%.[203]

Israel

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 750,000 | — |

| 2014 | 910,500 | +3.95% |

| 2015 | 950,000 | +4.34% |

| 2017 | 1,033,000 | +4.28% |

| 2018 | 1,079,000 | +4.45% |

| 2019 | 1,125,892 | +4.35% |

| 2020 | 1,175,088 | +4.37% |

| 2021 | 1,226,261 | +4.35% |

| 2022 | 1,279,528 | +4.34% |

| 2023 | 1,334,909 | +4.33% |

| Sources:[204][205][206] | ||

Israel has the largest Haredi population.[29] In 1948, there were about 35,000 to 45,000 Haredi Jews in Israel. By 1980, Haredim made up 4% of the Israeli population.[207] Haredim made up 9.9% of the Israeli population in 2009, with 750,000 out of 7,552,100; by 2014, that figure had risen to 11.1%, with 910,500 Haredim out of a total Israeli population of 8,183,400. According to a December 2017 study conducted by the Israeli Democracy Institute, the number of Haredi Jews in Israel exceeded 1 million in 2017, making up 12% of the population in Israel. In 2019, Haredim reached a population of almost 1,126,000;[204] the next year, it reached 1,175,000 (12.6% of total population),[205] and by the end of 2023, it reached 1,335,000, or 13.6% of total population.[206][208][209][210]

The number of Haredi Jews in Israel continues to rise rapidly, with their current population growth rate being 4% per year.[211] The number of children per woman is 7.2, and the share of Haredim among those under the age of 20 was 16.3% in 2009 (29% of Jews).[212]

By 2030, the Haredi Jewish community is projected to make up 16% of the total population, and by 2065, a third of the Israeli population, including non-Jews. By then, one in two Israeli children would be Haredi.[211][149][213][214] It is also projected that the number of Haredim in 2059 may be between 2.73 and 5.84 million, of an estimated total number of Israeli Jews between 6.09 and 9.95 million.[212][215]

The largest Israeli Haredi concentrations are in Jerusalem, Bnei Brak, Modi'in Illit, Beitar Illit, Beit Shemesh, Kiryat Ye'arim, Ashdod, Rekhasim, Safed, and El'ad. Two Haredi cities, Kasif and Harish, are planned.[citation needed]

United States

[edit]The United States has the second largest Haredi population, which has a growth rate on pace to double every 20 years. In 2000, there were 360,000 Haredi Jews in the US (7.2 per cent of the approximately 5 million Jews in the U.S.); by 2006, demographers estimate the number had grown to 468,000 (30% increase), or 9.4 per cent of all U.S. Jews.[216] In 2013, it was estimated that there were 530,000 total ultra-Orthodox Jews in the United States, or 10% of all American Jews.[217] By 2011, 61% of all Jewish children in Eight-County New York Area were Orthodox with Haredim making up 49%.[2]

In 2020, it was estimated that there were approximately 700,000 total ultra-Orthodox Jews in the United States, or 12% of all American Jews.[202] This number is expected to grow significantly in the coming years, due to high Haredi birth rates in America.

New York state

[edit]Most American Haredi Jews live in the greater New York metropolitan area.[218][219]

New York City

[edit]Brooklyn

[edit]

The largest centers of Haredi and Hasidic life in New York are found in Brooklyn.[220][221]

- In 1988, it was estimated that there were between 40,000 and 57,000 Haredim in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, Hasidim most belonging to Satmar.[222]

- The Jewish population in the Borough Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, estimated at 70,000 in 1983, is also mostly Haredi, and also mostly Hasidic.[199] The Bobov Hasidim are the largest single bloc that mainly live in Borough Park.[223]

- Crown Heights is the home base of the worldwide Chabad-Lubavitch movement, with its network of shluchim ("emissaries") heading Chabad houses throughout the Jewish world.[224][225]

- The Flatbush-Midwood,[226] Kensington,[227] Marine Park[228] neighborhoods have tens of thousands of Haredi Jews. They are also the centers for the major non-Hasidic Haredi yeshivas such as Yeshiva Torah Vodaas, Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin, Mir Yeshiva, as well as a string of similar smaller yeshivas. The Torah Vodaas and Chaim Berlin yeshivas[229] allow some students to attend college and university, presently at Touro College, and previously at Brooklyn College.[229]

Queens

[edit]The New York City borough of Queens is home to a growing Haredi population, mainly affiliated with the Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim and Yeshivas Ohr HaChaim in Kew Gardens Hills and Yeshiva Shaar Hatorah in Kew Gardens. Many of the students attend Queens College.[229] There are major yeshivas and communities of Haredi Jews in Far Rockaway,[227] such as Yeshiva of Far Rockaway and a number of others. Hasidic shtibelach exist in these communities as well, mostly catering to Haredi Jews who follow Hasidic customs, while living a Litvish or Modern Orthodox cultural lifestyle, although small Hasidic enclaves do exist, such as in the Bayswater section of Far Rockaway.

Manhattan

[edit]One of the oldest Haredi communities in New York is on the Lower East Side,[230] home to the Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem.

Washington Heights, in northern Manhattan, is the historical home to German Jews, with Khal Adath Jeshurun and Yeshiva Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch.[231] The presence of Yeshiva University attracts young people, many of whom remain in the area after graduation.[232]

Long Island

[edit]The Yeshiva Sh'or Yoshuv, together with many synagogues in the Lawrence neighborhood and other Five Towns neighborhoods, such as Woodmere and Cedarhurst, have attracted many Haredi Jews.[233]

Hudson Valley

[edit]The Hudson Valley, north of New York City, has the most rapidly growing Haredi communities, such as the Hasidic communities in Kiryas Joel[234][235][236] of Satmar Hasidim, and New Square of the Skver.[237] A vast community of Haredi Jews lives in the Monsey, New York, area.[238]

New Jersey

[edit]There are significant Haredi communities in Lakewood (New Jersey), home to the largest non-Hasidic Lithuanian yeshiva in America, Beth Medrash Govoha.[239] There are also sizable communities in Teaneck,[240] Englewood, Mahwah,[241] Passaic[242] and Edison, where a branch of the Rabbi Jacob Joseph Yeshiva opened in 1982. There is also a community of Syrian Jews favorable to the Haredim in their midst in Deal, New Jersey.[243]

Connecticut

[edit]The Haredi community of New Haven has close to 150 families and a number of thriving Haredi educational institutions.[244]

Maryland

[edit]Baltimore, Maryland, has a large Haredi population. The major yeshiva is Yeshivas Ner Yisroel, founded in 1933, with thousands of alumni and their families. Ner Yisroel is also a Maryland state-accredited college, and has agreements with Johns Hopkins University, Towson University, Loyola College in Maryland, University of Baltimore, and University of Maryland, Baltimore County, allowing undergraduate students to take night courses at these colleges and universities in a variety of academic fields.[229] The agreement also allows the students to receive academic credits for their religious studies.

Silver Spring, Maryland, and its environs has a growing Haredi community, mostly of highly educated and skilled professionals working for the United States government in various capacities, most living in Kemp Mill, White Oak, and Woodside,[245] and many of its children attend the Yeshiva of Greater Washington and Yeshivas Ner Yisroel in Baltimore.

Florida

[edit]Aventura,[246] Sunny Isles Beach, Golden Beach, Surfside[247] and Bal Harbour[248] are home to a large and growing Haredi population. The community is long-established in the area, with several synagogues including The Shul of Bal Harbour,[249] Young Israel of Bal Harbour, Aventura Chabad, Beit Rambam, Safra Synagogue of Aventura, and Chabad of Sunny Isles; mikvehs, Jewish schools and kosher restaurants. The community has recently grown much further, due to many Orthodox Jews from New York moving to Florida during the COVID-19 pandemic.[250][251]

North of Miami, the communities of Boca Raton, Lauderhill,[252] Boynton Beach, and Hollywood have significant Haredi populations.[253][254]

California

[edit]Los Angeles has many Haredi Jews, most living in the Pico-Robertson and Fairfax (Fairfax Avenue-La Brea Avenue) areas.[255][256]

Illinois

[edit]Chicago is home to the Haredi Telshe Yeshiva of Chicago, with many other Haredim living in the city.[257]

Pennsylvania

[edit]Haredim in Philadelphia primarily live in Bala Cynwyd, and the community is centered around Aish HaTorah and the Philadelphia Community Kollel.[258][259]

In Pittsburgh a small yeshiva opened in 1945. Today there are approximately 200 Chabad families living in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood.[260]

Kingston has a young growing Chabad Haredi community which has been growing steadily over the past 20 years since the first families moved there when a yeshiva was opened.[261]

Colorado

[edit]Denver has a large Haredi population of Ashkenazi origin, dating back to the early 1920s. The Haredi Denver West Side Jewish Community adheres to Litvak Jewish traditions (Lithuanian), and has several congregations located within their communities.[262]

Massachusetts

[edit]Boston and Brookline, Massachusetts, have the largest Haredi populations in New England.

Ohio

[edit]One of the oldest Haredi Lithuanian yeshivas, Telshe Yeshiva, transplanted itself to Cleveland in 1941.[263][264] Beachwood, Ohio has a large and growing Haredi community, and is a heavily Jewish suburb of Cleveland. The haredi community is centered around the Beachwood Kehilla and Green Road Synagogue, has a mikvah and a Jewish day school.[265]

United Kingdom

[edit]In 1998, the Haredi population in the Jewish community of the United Kingdom was estimated at 27,000 (13% of affiliated Jews).[199] The largest communities are located in London, particularly Stamford Hill, Golders Green, Hendon, Edgware; in Salford and Prestwich in Greater Manchester; and in Gateshead. A 2007 study asserted that three out of four British Jewish births were Haredi, who then accounted for 17% of British Jews (45,500 out of around 275,000).[216] Another study in 2010 established that there were 9,049 Haredi households in the UK, which would account for a population of nearly 53,400, or 20% of the community.[266][267] The Board of Deputies of British Jews has predicted that the Haredi community will become the largest group in Anglo-Jewry within the next three decades: In comparison with the national average of 2.4 children per family, Haredi families have an average of 5.9 children, and consequently, the population distribution is heavily biased to the under-20-year-olds. By 2006, membership of Haredi synagogues had doubled since 1990.[268][269]

An investigation by The Independent in 2014 reported that more than 1,000 children in Haredi communities were attending illegal schools where secular knowledge is banned, and they learn only religious texts, meaning they leave school with no qualifications and often unable to speak any English.[270]

The 2018 Survey by the Jewish Policy Research (JPR) and the Board of Deputies of British Jews showed that the high birth rate in the Haredi and Orthodox community reversed the decline in the Jewish population in Britain.[271]

In 2020 it was estimated that there were approximately 76,000 total ultra-Orthodox Jews in the United Kingdom, or 25% of all British Jews, a significant increase from 1998 and 2010.[202]

Elsewhere

[edit]About 25,000 Haredim live in the Jewish community of France, mostly people of Sephardic, Maghrebi Jewish descent.[199] Important communities are located in Paris(19th arrondissement),[272] Strasbourg, and Lyon.

Other important communities, mostly of Ashkenazi Jews, are the Antwerp community in Belgium, as well as in the Swiss communities of Zürich and Basel, and in the Dutch community in Amsterdam. There is also a Haredi community in Vienna, in the Jewish community of Austria. Other countries with significant Haredi populations include: Canada, with a total number of 30,000 Haredim,[202] with large Haredi centres in Montreal and Toronto; South Africa, primarily in Johannesburg; and an estimated 7,500 Haredim in Australia,[202] centred in Melbourne. Haredi communities also exist in Argentina, especially in Buenos Aires, and in Brazil, primarily in São Paulo. A Haredi city is under construction (2021) in Mexico near Ixtapan de la Sal.[273] Decades after The Holocaust, Haredim are growing again in Budapest, opening several new synagogues and two mikvehs in the city over the past couple of years.[274][275]

| Country | Year | Core Jewish Population | Haredi Population[276] | % Haredi | Annual growth rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Israel | 2023 | 7,200,000 | 1,335,000[206] | 17% | 4%[206] |

| United States | 2020 | 6,000,000 | 700,000[217][202][276] | 12% | 5.4%[216] |

| United Kingdom | 2020 | 292,000 | 76,000[202] | 26% | 4%[277] |

| Canada | 2020 | 393,500 | 30,000[276] | 8% | |

| Argentina | 2020 | 175,000 | 13,500[276] | 8% | |

| France | 2020 | 446,000 | 12,000 | 3% | |

| Belgium | 2020 | 28,900 | 10,000 | 35% | |

| South Africa | 2020 | 52,000 | 10,000 | 19% | |

| Mexico | 2020 | 40,000 | 7,500 | 19% | |

| Australia | 2020 | 118,000 | 7,500[276] | 6% | |

| Switzerland | 2020 | 18,400 | 3,300 | 18% | |

| Germany | 2020 | 118,000 | 3,000 | 3% | |

| Austria | 2020 | 10,300 | 2,000 | 19% | |

| Spain | 2020 | 12,900 | 104 | 0.8% | |

| Hungary | 2020 | 46,800 | 885[276] | 1.9% | |

| Netherlands | 2020 | 29,700 | 455 | 1.5% | |

| Poland | 2020 | 4,500 | 59 | 1.3% | |

| Sweden | 2020 | 14,900 | 34 | 0.2% |

Present leadership and organizations

[edit]Rabbis and rabbinic authority

[edit]Notwithstanding the authority of Chief Rabbis of Israel (Ashkenazi: David Lau, Sephardi: Yitzhak Yosef) or the wide acknowledgement of specific rabbis in Israel (for example, Rabbi Gershon Edelstein of the non-Hasidic Lithuanian Jews, and Yaakov Aryeh Alter who heads the Ger Hasidic dynasty, the largest Hasidic group in Israel), Haredi and Hasidic factions generally align with the independent authority of their respective group leaders.

Major representative groups and political parties

[edit]- World Agudath Israel (including Agudath Israel of America)

- Edah HaChareidis (representing anti-Zionist Haredi groups in and around Jerusalem, including Satmar, Dushinsky, Toldos Aharon, Toldos Avrohom Yitzchok, Mishkenos HoRoim, Spinka, Brisk, and a section of other Litvish Haredim)

Other representative associations may be linked to specific Haredi and Hasidic groups. For example:

- Breslov Hasidism maintains an umbrella group known as Vaad Olami D'Chasedai Breslov

- Chabad Lubavitch[225] maintains an international network of organizations, and is formally represented under the umbrella group Agudas Chasidei Chabad

- The Hasidic umbrella group Central Rabbinical Congress is associated with Satmar

Haredi political parties in Israel include:

- Shas (representing Mizrahi and Sephardic Haredim)

- United Torah Judaism (alliance representing Ashkenazi Haredim)

- Agudat Yisrael (representing many Hasidic Jews)

- Degel HaTorah (representing Lithuanian Jews)

- U'Bizchutan (representing Haredi women and the Orthodox Jewish feminist movement)

- Noam

- Yachad

Controversies

[edit]Shunning

[edit]People who decide to leave Haredi communities are sometimes shunned and pressured or forced to abandon their children.[144][147][148]

Pedophilia and sexual abuse cases

[edit]Cases of pedophilia, sexual violence, assaults, and abuses against women and children occur in roughly the same rates in Haredi communities as in the general population; however, they are rarely discussed or reported to the authorities, and frequently downplayed by members of the communities.[278][279][280][281][282][283][284][285]

Divorce coercion

[edit]To receive a religious divorce, a Jewish woman needs her husband's consent in the form of a get (Jewish divorce document). Without this consent, any future offspring of the wife would be considered mamzerim (bastards/impure). If the circumstances truly warrant a divorce, and the husband is unwilling, a dayan (rabbinic judge) has the prerogative of instituting community shunning measures to "coerce him until he agrees", with physical force reserved only for the rarest of cases.[286][17][287]

The New York divorce coercion gang was a Haredi Jewish group that kidnapped, and in some cases tortured, Jewish men in the New York metropolitan area to force them to grant their wives gittin (religious divorces). The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) broke up the group after conducting a sting operation against the gang in October 2013. The sting resulted in the prosecution of four men, three of whom were convicted in late 2015.[288]

Political controversies involving Haredi communities and parties in Israel

[edit]In January 2023, the Times of Israel reported that Haredi Jewish citizens in Israel pays just 2% of the country's total income tax revenues, despite making up 12% of the nation's population. Furthermore, the article's author described their communities as an epicenter of poverty, with over 60% of Haredi households classified as poor on the government's socioeconomic index, with that figure remaining nearly constant in every Haredi community.[289]

While this disparity has been present in Israel for decades, it has garnered more attention since December 2022 for numerous reasons. First, Haredi families have the highest fertility rate in Israel, at 6.6 births per woman. In comparison, the average fertility rate in Israel is much lower, at 2.9 per woman. Current projections estimate that the Haredi population will double by 2036, and they will comprise 16% of the total population by 2030.[290]

The second aspect of the controversy surrounds their political connections to Israel's Religious Zionist alliance. Historically, they have remained politically uninvolved, but since the 1990s, they have continuously engaged more. Today, members of Israel's ultra-Orthodox community have long enjoyed benefits unavailable to many other Israeli citizens: exemption from army service for Torah students, government stipends for those choosing full-time religious study over work, and separate schools that receive state funds even though their curriculums often do not fully teach government-mandated subjects. Today, many Israeli Haredi men do not work, preferring to study the Torah full-time, since they receive government funding for it, thus resulting in their high poverty rate.[291]

See also

[edit]- Jewish religious movements

- Relationships between Jewish religious movements

- Schisms among the Jews#Hasidim and Mitnagdim

- Who is a Jew?

References

[edit]- ^ Nora L. Rubel (2010). Doubting the Devout: The Ultra-Orthodox in the Jewish American Imagination. Columbia University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-231-14187-1. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

Mainstream Jews have—until recently—maintained the impression that the ultraorthodox are the 'real' Jews.

- ^ a b "Jewish Community Study of New York: 2011" (PDF). UJA Federation of New York. 2011. p. 218. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c Stadler 2009, p. 4

- ^ Ben-Yehuda 2010, p. 17

- ^ White, John Kenneth; Davies, Philip John (1998). Political Parties and the Collapse of the Old Orders. State University of New York Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-7914-4068-1.

- ^ Kosmin, Barry Alexander; Keysar, Ariela (2009). Secularism, Women & the State: The Mediterranean World in the 21st Century. Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-692-00328-2.

- ^ Sokol, Sam. "Introducing the New, Improved Haredim", The Tower Magazine, May 2013. accessed June 28, 2024. "The term 'Haredi' comes from the Hebrew word for trembling or, depending on context, anxiety. Like the American Shakers and Quakers, it is a direct reference to the fear of God, or of transgressing His laws, that lies at the core of the lives of adherents."

- ^ Markoe, Lauren (February 6, 2014). "Should ultra-Orthodox Jews be able to decide what they're called?". Washington Post. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c Philologos [Hillel Halkin] (February 17, 2013). "Just How Orthodox Are They?". The Forward. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ May, Max B. (1916). Isaac Mayer Wise: Founder of American Judaism: A Biography (PDF). New York: G.P. Putnam's. p. 71.

- ^ a b Ayalon, Ami (1999). "Language as a barrier to political reform in the Middle East", International Journal of the Sociology of Language, Volume 137, pp. 67–80: "Haredi" has none of the misleading religious implications of "ultra-Orthodox": in the words of Shilhav (1989: 53),[full citation needed] "They are not necessarily [objectively] more religious, but religious in a different way."; and "'Haredi' ... is preferable, being a term commonly used by such Jews themselves ... Moreover, it carries none of the venom often injected into the term 'ultra-Orthodox' by other Jews and, sadly, by the Western media ..."

- ^ a b Sources describing the term as pejorative or derogatory include:

- Kobre, Eytan. One People, Two Worlds. A Reform Rabbi and an Orthodox Rabbi Explore the Issues That Divide Them, reviewed by Eytan Kobre, Jewish Media Resources, February 2003. Retrieved August 25, 2009. "Indeed, the social scientist Marvin Schick calls attention to the fact that 'through the simple device of identifying [some Jews] ... as "ultra-Orthodox", ... [a] pejorative term has become the standard reference term for describing a great many Orthodox Jews... No other ethnic or religious group in this country is identified in language that conveys so negative a message.'"

- Goldschmidt, Henry. Race and Religion among the Chosen Peoples of Crown Heights, Rutgers University Press, 2006, p. 244, note 26. "I am reluctant to use the term 'ultra-Orthodox', as the prefix 'ultra' carries pejorative connotations of irrational extremism."

- Longman, Chia. "Engendering Identities as Political Processes: Discources of Gender Among Strictly Orthodox Jewish Women", in Rik Pinxten, Ghislain Verstraete, Chia Longmanp (eds.) Culture and Politics: Identity and Conflict in a Multicultural World, Berghahn Books, 2004, p. 55. "Webber (1994: 27) uses the label 'strictly Orthodox' when referring to Haredi, seemingly more adequate as a purely descriptive name, yet carrying less pejorative connotations than ultra-Orthodox."

- Shafran, Avi. "Don't Call Us 'Ultra-Orthodox'", The Jewish Daily Forward, February 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2014. "Considering that other Orthodox groups have self-identified with prefixes like 'modern' or 'open', why can't we Haredim just be, simply, 'Orthodox'? Our beliefs and practices, after all, are those that most resemble those of our grandparents. But, whatever alternative is adopted, 'ultra' deserves to be jettisoned from media and discourse. We Haredim aren't looking for special treatment, or to be called by some name we just happen to prefer. We're only seeking the mothballing of a pejorative."

- ^ Stolow, Jeremy (January 1, 2010). Orthodox by Design: Judaism, Print Politics, and the ArtScroll Revolution. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520264250.

- ^ Shafran, Avi (February 4, 2014). "Don't Call Us 'Ultra-Orthodox". Forward. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Lipowsky, Josh. "Paper loses 'divisive' term" Archived August 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Jewish Standard. January 30, 2009. "... JTA [Jewish Telegraphic Agency] faced the same conundrum and decided to do away with the term, replacing it with 'fervently Orthodox'. ... 'Ultra-Orthodox' was seen as a derogatory term that suggested extremism."

- ^ "Orthodox Judaism". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

Orthodox Judaism claims to preserve Jewish law and tradition from the time of Moses.

- ^ a b c Goldstein, Joseph; Schwirtz, Michael (October 10, 2013). "U.S. Accuses 2 Rabbis of Kidnapping Husbands for a Fee". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ Heilman, Samuel. "Ultra-Orthodox Jews Shouldn't Have a Monopoly on Tradition". The Forward. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ Heilman, Samuel C. (1976). Synagogue Life: A Study in Symbolic Interaction. Transaction Publishers. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1412835497.

- ^ Ritzer, George (2011). Ryan, J. Michael (ed.). The concise encyclopedia of sociology. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 335. ISBN 978-1444392647.

- ^ Donna Rosenthal. The Israelis: Ordinary People in an Extraordinary Land. Simon and Schuster, 2005. p. 183. "Dossim, a derogatory word for Haredim, is Yiddish-accented Hebrew for 'religious'."

- ^ Nadia Abu El-Haj. Facts on the ground: Archaeological practice and territorial self-fashioning in Israeli society. University of Chicago Press, 2001. p. 262.

- ^ Benor, Sarah Bunin (2012). Becoming frum how newcomers learn the language and culture of Orthodox Judaism. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0813553917.

- ^ For example: Arnold Eisen, Rethinking Modern Judaism, University of Chicago Press, 1998. p. 3.

- ^ a b Rubel, Nora L. (November 1, 2009). Doubting the Devout: The Ultra-Orthodox in the Jewish American Imagination. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231512589.

- ^ Caplan, Kimmy (October 27, 2016). "Post-World War II Orthodoxy". Jewish Studies. pp. 9780199840731–0139. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199840731-0139. ISBN 978-0-19-984073-1.

First and foremost, as Katz 1986 and Samet 1988 prove, notwithstanding the overall Orthodox perception that it is the only authentic expression of traditional Judaism and although it is related to traditional Judaism, Orthodoxy is a modern European phenomenon which gradually emerged in response to the gradual demise of traditional Jewish societies, the rise of the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah), Jewish Reforms, secularization, and various additional processes which developed throughout the 19th century.

- ^ Slifkin, Natan. "The Novelty of Orthodoxy" (PDF).

The Orthodox simply viewed themselves as authentically continuing the ways of old. Originally, historians viewed them in the same way, considering them less interesting than more visibly new forms of Judaism such as the haskalah and Reform Judaism. But beginning with the works of Joseph Ben-David2 and Jacob Katz,3 it was realized in academic circles that all of this was nothing more than a fiction, a romantic fantasy. The very act of being loyal to tradition in the face of the massive changes of the eighteenth century forced the creation of a new type of Judaism. It was traditionalist rather than traditional.

- ^ Kogman, Tal (January 7, 2017). "Science and the Rabbis: Haskamot, Haskalah, and the Boundaries of Jewish Knowledge in Scientific Hebrew Literature and Textbooks". The Leo Baeck Institute Year Book. 62: 135–149. doi:10.1093/leobaeck/ybw021.

- ^ a b Raysh Weiss. "Haredim (Charedim), or Ultra-Orthodox Jews". My Jewish Learning.

What unites haredim is their absolute reverence for Torah, including both the Written and Oral Law, as the central and determining factor in all aspects of life. ... In order to prevent outside influence and contamination of values and practices, haredim strive to limit their contact with the outside world.

- ^ "Orthodox Judaism". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

Haredi Judaism, on the other hand, prefers not to interact with secular society, seeking to preserve halakha without amending it to modern circumstances and to safeguard believers from involvement in a society that challenges their ability to abide by halakha.

- ^ "Ner Tamid Emblem Workbook" (PDF). January 20, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2012.

- ^ "YIVO | Schick, Mosheh". Yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Kolmyya, Ukraine (Pages 41-55, 85-88)". Jewishgen.org. February 12, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Rabbi Shimon Sofer • "The Author of Michtav Sofer"". Hevratpinto.org. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "New Religious Party". Archive.jta.org. September 13, 1934. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Berlin Conference Adopts Constitution for World Union Progressive Judaism". Archive.jta.org. August 21, 1928. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Agudah Claims 16,205 Palestine Jews Favor Separate Communities". Archive.jta.org. February 28, 1929. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Palestine Communities Ordinance Promulgated". Archive.jta.org. July 20, 1927. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Rabbi Dushinsky Installed As Jerusalem Chief Rabbi of Orthodox Agudath Israel". Archive.jta.org. September 3, 1933. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Assaf, David (2010). "Hasidism: Historical Overview". The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. p. 2.

- ^ MacQueen, Michael (2014). "The Context of Mass Destruction: Agents and Prerequisites of the Holocaust in Lithuania". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 12 (1): 27–48. doi:10.1093/hgs/12.1.27. ISSN 1476-7937.

- ^ Weiss, Raysh (August 12, 2023). "Haredim (Chareidim)". myjewishlearning.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Wertheimer, Jack. "What You Don't Know About the Ultra-Orthodox." Archived July 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Commentary Magazine. 1 July 2015. 4 September 2015.

- ^ Šelomo A. Dešen; Charles Seymour Liebman; Moshe Shokeid (January 1, 1995). Israeli Judaism: The Sociology of Religion in Israel. Transaction Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4128-2674-7.

The number of baalei teshuvah, "penitents" from secular backgrounds who become Ultraorthodox Jews, amounts to a few thousand, mainly between the years 1975-1987, and is modest, compared with the natural growth of the haredim; but the phenomenon has generated great interest in Israel.

- ^ Harris 1992, p. 490: "This movement began in the US, but is now centred in Israel, where, since 1967, many thousands of Jews have consciously adopted an ultra-Orthodox lifestyle."

- ^ Weintraub 2002, p. 211: "Many of the ultra-Orthodox Jews living in Brooklyn are baaley tshuva, Jews who have gone through a repentance experience and have become Orthodox, though they may have been raised in entirely secular Jewish homes."

- ^ Returning to Tradition: The Contemporary Revival of Orthodox Judaism, By M. Herbert Danzger: "A survey of Jews in the New York metropolitan area found that 24% of those who were highly observant (defined as those who would not handle money on the Sabbath) had been reared by parents who did not share such scruples. [...] The ba'al t'shuva represents a new phenomenon for Judaism; for the first time there are not only Jews who leave the fold ... but also a substantial number who "return". p. 2; and: "These estimates may be high... Nevertheless, as these are the only available data we will use them... Defined in terms of observance, then, the number of newly Orthodox is about 100,000... despite the number choosing to be orthodox the data do not suggest that Orthodox Judaism is growing. The survey indicates that although one in four parents were Orthodox, in practice, only one in ten respondents are Orthodox" p. 193.

- ^ Lehmann, David; Siebzehner, Batia (August 2009). "Power, Boundaries and Institutions: Marriage in Ultra-Orthodox Judaism". European Journal of Sociology. 50 (2): 273–308. doi:10.1017/s0003975609990142. S2CID 143455323.

- ^ Bob, Yonah Jeremy (April 19, 2013). "Sephardi haredim complain to court about 'ghettos'". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ Silberstein 1993, p. 17.

- ^ Tehranian 1997, p. 324.

- ^ Waxman, Chaim. "Winners and Losers in Denominational Memberships in the United States". Archived from the original on March 7, 2006.

- ^ Ilan, Shahar (July 12, 2012). "The myth of Haredi moral authority". Haaretz.com. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ Munson, Henry L. Jr. (November 26, 2019). "Fundamentalism - The Haredim". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ Frey, Rebecca Joyce (2007). Fundamentalism. Infobase Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4381-0899-5.

- ^ Heilman, Samuel C.; Friedman, Menachem (July 1994). "Religious Fundamentalism and Religious Jews: The Case of the Haredim". In Marty, Martin E.; Appleby, R. Scott; American Academy of Arts and Sciences (eds.). Fundamentalisms Observed. University of Chicago Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-226-50878-8.