History of Cornell University

The history of Cornell University begins when its two founders, Andrew Dickson White of Syracuse and Ezra Cornell of Ithaca, met in the New York State Senate in January 1864. Together, they established Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, in 1865. The university was initially funded by Ezra Cornell's $400,000 endowment and by New York's 989,920-acre (4,006.1 km2) allotment of the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862.

However, even before Ezra Cornell and Andrew White met in the New York Senate, each had separate plans and dreams that would draw them toward their collaboration in founding Cornell. White believed in the need for a great university for the nation that would take a radical new approach to education; and Cornell, who had great respect for education and philanthropy, desired to use his money "to do the greatest good." Abraham Lincoln's signing of Vermont Senator Justin Morrill's Land Grant Act into law was also critical to the formation of many universities, including Cornell, in the post–Civil War era.

Precursors

[edit]The first person to conceive of a single great university for the state of New York, a generation before Cornell, was the visionary, abolitionist, and philanthropist Gerrit Smith, from very much Upstate Peterboro. When the initial meeting of the very unpopular New York State Anti-Slavery Society was driven out of Utica (Oneida County) by the Mayor, it continued the next day in Smith's house.

A new college was to be established in upstate New York. This Central College, as it came to be called, was the abolitionists' college, taking over that role from the failed Oneida Institute (whose other descendent was Oberlin College). Like Oneida, it was part of the manual labor college movement, in which students were to work for some hours each day in addition to study, such work being spiritually and economically beneficial. In McGraw, it was 40 miles (64 km) west of Peterboro.

Central (1849–1860) was the first college in the United States that from its very first day was open to women, blacks, and Native Americans on an equal basis, something Oberlin was not. It was also the first to hire black faculty, and have them teaching a class with white students. That it allowed female students was just as unusual as allowing black students.

Central was financially unviable and victim of a lot of racial prejudice; some parents would not have their children study at "a nigger college", as it was called. When bankrupt, the entire college was taken over by Smith, who assumed its debts along with its meager assets.[1][2][3]

Founders

[edit]

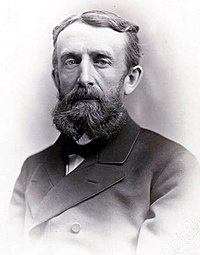

As newly elected members of the state senate, Cornell chaired the Committee of Agriculture, and White was the chair of the Committee of Literature, which dealt with educational matters. Hence, both chaired committees with jurisdiction over bills allocating the land grant, which was to be used for instruction in "without excluding other scientific and classical studies and including military tactic, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts".[4] Yet their eventual partnership seemed unlikely. Although both valued egalitarianism, science, and education, they had come from two very different backgrounds. Ezra Cornell, a self-made businessman and austere, pragmatic telegraph mogul, made his fortune on the Western Union Telegraph Company stock he received during the consolidation that led to its formation.[5] Cornell, who had been poor for most of his life, suddenly found himself looking for ways that he could do the greatest good for with his money. He wrote, "My greatest care now is how to spend this large income to do the greatest good to those who are properly dependent on me, to the poor and to posterity."[6] Cornell's self-education and hard work would lead him to the conclusion that the greatest end for his philanthropy was in the need of colleges for the teaching of practical pursuits such as agriculture, the applied sciences, veterinary medicine and engineering, and in finding opportunities for the poor to attain such an education.

Andrew Dickson White entered college at the age of 16 in 1849. White dreamed of going to one of the elite eastern colleges, but his father sent him to Geneva Academy (later known as the Hobart and William Smith Colleges), a small Episcopal college. At Geneva, White would read about the great colleges at Oxford University and at the University of Cambridge; this appears to be his first inspiration for "dreaming of a university worthy of the commonwealth [New York] and of the nation." This dream would become a lifelong goal of White's. After a year at Geneva, White convinced his father to send him to Yale University.[7] For White, Yale was a great improvement over Geneva, but he found that even at one of the country's great universities there was "too much reciting by rote and too little real intercourse."

In the late 1850s, while White served as a professor of history at the University of Michigan, he continued to develop his thoughts on a great American university.[8] He was influenced by both the curriculum, which was more liberal than at the Eastern universities, and by the administration of the university as a secular institution.[9]

Conception

[edit]White had been duly impressed by a bill introduced by Cornell in one of his first actions as a state senator: the incorporation of a large public library for Ithaca for which Cornell had donated $100,000. White was struck by not only his generosity, but also "his breadth of mind". He wrote:

The most striking sign of this was his mode of forming a board of trustees; for, instead of the usual effort to tie up the organization forever in some sect, party or clique, he had named the best men of his town—his political opponents as well as his friends; and had added to them the pastors of all the principal churches, Catholic and Protestant.[9]

Yet, Cornell and White soon found themselves on opposite sides of a battle that would in the end lead to the creation of Cornell University. In 1863, the legislature had granted the proceeds of the land grant to the People's College in Havana (now Montour Falls), with conditions that would need to be met within a certain time frame. Because the Morrill Act set a five-year limit on each state identifying a land grant college, and it seemed unlikely that the People's College would meet its conditions, the legislature was ready to select a different school. Initially, Cornell, as a member of the Board of Trustees of the New York State Agricultural College at Ovid, wanted half the grant to go to that school. However, White "vigorously opposed this bill, on the ground that the educational resources of the state were already too much dispersed".[10] He felt that the grant would be most effective if it were used to establish or strengthen a comprehensive university.

Still working to send part of the grant to the Agricultural College, on September 25, 1864, in Rochester, New York, Cornell announced his offer to donate $300,000 (soon thereafter increased to $500,000) if part of the land grant could be secured and the trustees moved the college to Ithaca.[9] White did not relent; however, he said he would support a similar measure that did not split up the grant.[9] Thus began the collaboration between Ezra Cornell and Andrew D. White that became Cornell University.

Establishment

[edit]

On February 7, 1865, Andrew D. White introduced an act to the State Senate "to establish the Cornell University", which appropriated the full income of the sale of lands given to New York under the Morrill Act to the university. But, while Cornell and White had come to an agreement, they faced fierce opposition, including from the People's College in Havana,[11][12] the Agricultural College at Ovid,[13] and dozens of other institutions across the state vying for a share of the land grant funds; from religious groups, who opposed the proposed composition of the university's board of trustees; and even from the secular press, some of whom thought Cornell was swindling the state out of its federal land grant. To placate legislators representing Ovid, White arranged for the Willard State Asylum for the Insane to be located on the land held for the Agricultural College.[14] The bill limited the total amount of property or endowment that Cornell University could hold to $3 million.[15]

The bill was modified at least twice in attempts to attain the votes necessary for passage. In the first change, the People's College was given three months to meet certain conditions for which it would receive the land grant under the 1863 law. The second came from a Methodist faction, which wanted a share of the grant for Genesee College. They agreed to a quid-pro-quo donation of $25,000 from Ezra Cornell in exchange for their support. Cornell insisted the bargain be written into the bill.[9] The bill was signed into law by Governor Reuben E. Fenton on April 27, 1865.[16] On July 27, the People's College lost its claim to the land grant funds, and the building of Cornell University began.

From 1865 to 1868, the year the university opened, Ezra Cornell and Andrew D. White worked in tireless collaboration to build their university. Cornell oversaw the construction of the university's first buildings, starting with Morrill Hall, and spent time investing the federal land scrip in western lands for the university that would eventually net millions of dollars,[9] while White, who was unanimously elected the first President of Cornell University by the Board of Trustees on November 21, 1866, began making plans for the administrative and educational policies of the university. To this end, he traveled to France, Germany, and England "to visit model institutions, to buy books and equipment, to collect professors". White returned from Europe to be inaugurated as Cornell's president in 1868, and he remained leader of Cornell until his retirement from the presidency in 1885.

Opening

[edit]

The university's Inauguration Day took place on October 7, 1868.[17] The previous day, each of the candidates who showed up in Ithaca was given an entrance examination. There were 412 successful applicants; with this initial enrollment, Cornell's first class was, at the time, the largest entering class at an American university.[18]

On the occasion, Ezra Cornell delivered a brief speech. He said, "I hope we have laid the foundation of an institution which shall combine practical with liberal education. ... I believe we have made the beginning of an institution which will prove highly beneficial to the poor young men and the poor young women of our country." His speech included another statement which later became the school's motto, "I would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study."[19]

Two other Ezra Cornell-founded, Ithaca institutions played a role in the rapid opening of the university. The Cornell Free Library, a public library in downtown Ithaca which opened in 1866,[20] served as a classroom and library for the first students. Also Cascadilla Hall, which was constructed in 1866 as a water cure sanitarium,[21] served at the university's first dormitory.[18]

Cornell was among the first universities in the United States to admit women alongside men. The first woman was admitted to Cornell in 1870, although the university did not yet have a women's dormitory. On February 13, 1872, Cornell's board of trustees accepted an offer of $250,000 from Henry W. Sage to build such a dormitory. During the construction of Sage College (now home to the Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management as Sage Hall) and after its opening in 1875, the admittance of women to Cornell continued to increase.

Significant departures from the standard curriculum were made at Cornell under the leadership of Andrew D. White. In 1868, Cornell introduced the elective system, under which students were free to choose their own course of study. Harvard University would make a similar change in 1872, soon after the inauguration of Charles W. Eliot in 1869.[22]

It was the success of the egalitarian ideals of the newly established Cornell, a uniquely American institution, that would help drive some of the changes seen at other universities throughout the next few decades, and would lead educational historian Frederick Rudolph to write:

Andrew D. White, its first president, and Ezra Cornell, who gave it his name, turned out to be the developers of the first American university and therefore the agents of revolutionary curricular reform.[23]

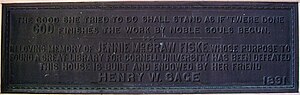

In 1892, the university library was opened. Known today as Uris Library, it was the result of a gift from Henry W. Sage in memory of Jennie McGraw. In her will, she left $300,000 to her husband Willard Fiske, $550,000 to her brother Joseph and his children, $200,000 to Cornell for a library, $50,000 for construction of McGraw Hall, $40,000 for a student hospital, and the remainder to the university for whatever use it saw fit. However, the university's charter limited its property holdings to $3,000,000,[24] and Cornell could not accept the full amount of McGraw's gift. When Fiske realized that the university had failed to inform him of this restriction, he launched a legal assault to re-acquire the money, known as The Great Will Case. The United States Supreme Court eventually affirmed the judgment of the New York Court of Appeals that Cornell could not receive the estate on May 19, 1890, with Justice Samuel Blatchford giving the majority opinion.[25][26] However, Sage then donated $500,000 to build the library instead.[26]

Coeducation

[edit]Background

[edit]

In the mid 19th century, coeducation was still a new and controversial idea. Most colleges were exclusively male, and several women's colleges had been founded as a response. But prior to Cornell's charter in 1865, few colleges were devoted to coeducation. (It is worth noting that coeducation did not catch on broadly with elite northeastern schools, including other Ivy League schools, until the 1960s[27]) Oberlin College and University of Michigan were two coeducational colleges which predated Cornell's founding, and provided models for Cornell.

The carnage of the American Civil War had introduced women into new areas of experience and leadership, and because of war casualties women outnumbered men in the United States.[28]: 40-42 Central New York, and especially nearby Seneca Falls, was the center of the 19th-century women's rights movement. Cornell's founders Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White favored coeducation and had deliberately included language in the school's charter specifying that it would offer instruction to "any person". Still, the school had no explicit policy about accepting women, and Cornell enrolled its first class in 1868 with 412 men and no women.[28]: 55 In theory, the school would accept any person who could pass the admission requirements, but no facilities existed for women at its start, and the reality of admitting women was not immediately clear.

In September 1870, one Jennie Spencer, of Cortland, New York, passed a state scholarship examination thus becoming Cornell's first female student.[28]: 65-66 [29] Because of the lack of housing for women on campus, Spencer lived in downtown Ithaca, requiring her to walk up the hill for classes. This was an arduous task in Ithaca's harsh weather, considering the condition of the roads and the bulky Victorian dress of the time.[28]: 65-66 Spencer reluctantly left Cornell without graduating, but her situation raised awareness of the need for housing and facilities for women on campus.[28]: 65-66

Sage College

[edit]

Henry W. Sage, local businessman and philanthropist, was an advocate for coeducation and promised to donate a sum of $250,000 on the condition that Cornell admit women on equal footing as men.[28]: 74 This financial incentive, together with the support of both Cornell and White, led the trustees to formally vote to admit women starting April 1872.[28]: 74 This decision caused Goldwin Smith, Cornell's most illustrious professor, to resign; Smith was convinced that admitting women would destroy Cornell's academic reputation.[28]: 76-77

In May 1873[28]: 77 the cornerstone was laid for Sage College for Women, a residence built specially to accommodate 120 women students.[28]: 74 [30]

In the fall of 1875, Cornell admitted forty-nine women.[28]: 84 Twenty-nine lived in the newly opened Sage College; another twenty lived in boarding houses or with relatives.[28]: 84 In 1895, 224 women were enrolled in the university, 104 of whom lived in Sage College.[28]: 87

Early growth

[edit]

As women entered the university, the university made accommodations for them. In 1884, Henry Sage endowed several of the first scholarships in the nation earmarked especially for women.[28]: 86 In 1885, Cornell established a course in social work, a field seen as suited to women's academic interests.[28]: 87 In 1900, a correspondence course for farmer's wives was begun by Martha Van Rensselaer, which evolved into the College of Home Economics, later the College of Human Ecology.[32]

In 1895, a study was conducted to review the first twenty years of coeducation at Cornell. The study found that a total of 990 women had attended the university; of these, 325 received degrees,[note 1] of which fifty-five were graduate degrees.[28]: 87 Seventeen Cornell graduates went on to further advanced study, many of whom were the first women to gain admission to those institutions.[28]: 88 Although a small percentage of the student body, women students per capita were found to outperform their male counterparts in terms of scholarships, fellowships, and other academic honors.[28]: 87

Some early notable women Cornell students included embryologist Susanna Phelps Gage, engineer Kate Gleason, Bryn Mawr president M. Carey Thomas, Wellesley president Julia Irvine, social reformer Florence Kelley '82, naturalist Anna Botsford Comstock '85, psychologist Margaret Floy Washburn Ph.D. '94, surgeon Emily Barringer '97, M.D. '01, lawyer/suffragist Gail Laughlin L.L.B. '98, editor and poet Jessie Redmon Fauset '05 and educator Martha Van Rensselaer '09.[28]: 89-92

In 1911, philanthropist Olivia Sage donated $300,000 for the construction of a second women's dormitory, Risley Residential College. The building was named for her late husband's mother.[28]: 89-92

Separate lives

[edit]The requirement that women (at least freshman women) must live in dormitories, which started in 1884,[33] served to constrain female student admissions until 1972, when Cornell dropped its freshman dorm residency requirement. As a result, the academic admission standards for women in each college were typically higher than the corresponding standards for men.[34] In general, women have been over-represented in certain schools and under-represented in others. For example, the NYS College of Home Economics and the Cornell School of Nursing historically drew a disproportionate number of women students, while the College of Engineering attracted fewer women.

Early in the history of the university, female students were separated from male students in many ways.[35] For example, they had a separate entrance and lounges in Willard Straight Hall, a separate student government, and a separate page (edited by women) in The Cornell Daily Sun. The male students were required to take "drill" (a precursor to ROTC), but the women were exempt. One account of the history of coeducation at Cornell claims that in the very beginning, "[m]ale students were almost unanimously opposed to co-education, and vigorously protested the arrival of a group of 16 women, who promptly formed a women's club with a broom for their standard, and 'In hoc signo vinces' as their motto."[33] In the 1870s and 1880s, female Cornell students on campus were generally ignored by male students.[33][36] Women did not have a formal role in the annual commencement ceremony until 1935, when the senior class selected a woman to be Class Poet.[37] In 1936, the Willard Straight Hall Board of Managers voted to allow women to eat in its cafeteria.[38] Until the 1970s, male students resided in west campus dormitories while women were housed in the north campus.

As of 2019, the only remaining women's dormitory is Balch Hall, due to a restriction in the gift that funded it.[39] Lyon Hall (which for most of its history was a men-only dormitory), also currently disallows male residents on its lower floors.[40] All other dormitories were converted to co-educational housing in the late 1970s.

Veterinary College

[edit]The NYS College of Veterinary Medicine was an early pioneer in educating women, bestowing the first DVM degree on a woman in the United States, Florence Kimball, in 1910.[41] However, until the early 1980s, the Vet College limited the number of women in each entering class to four or less, regardless of female applicants' qualifications.[42]

Title IX

[edit]With the implementation of Title IX in the mid-1970s, Cornell significantly expanded its athletic offerings for women. The Department of Physical Education and Athletics moved from having all women's activities housed in Helen Newman Hall to having men's and women's programs in all facilities.

Nonsectarianism and religion on campus

[edit]

Up until the time of Cornell's founding, most prominent American colleges had ties to religious denominations.[43] Cornell was founded as a non-sectarian school, but had to compete with church-sponsored institutions for gaining New York's land-grant status. A.D. White noted in his inaugural address, "We will labor to make this a Christian institution, a sectarian institution may it never be."[44] However, the university has made provision for voluntary religious observance on campus. Currently, the University Charter provides, "Persons of every religious denomination, or of no religious denomination, shall be equally eligible to all offices and appointments".[45] Through the 20th century, the University Charter also required that a majority of trustees could not be of any single denomination. Sage Chapel, a non-denominational house of worship opened in 1875.[44] Since 1929, the Cornell United Religious Works (CURW) has been an umbrella organization for the campus chaplains sponsored by different denominations and faiths.[46] Perhaps the most newsworthy of the chaplains was Daniel Berrigan who, while Assistant Director of CURW, became a national leader in protesting the Vietnam War.[47][48] In 1971, the social activism aspects of CURW were spun off into a separate Center for Religion, Ethics and Social Policy (CRESP). In 2006, CRESP was reorganized as Cornell's Center for Transformative Action.[49]

In the late 1950s, the National Council of Young Israel (NCYI) leased a house across the street from the university and established a Jewish living center and kosher dining hall. The Cornell Young Israel chapter became the Center for Jewish Living, and a new Foundation for Kosher Observance at Cornell, Inc. was established so that the university's dining department would operate both a kosher kitchen at the center as well as serving kosher food on the North Campus.[50]

Since the 1870s, Cornell's system of fraternities and sororities grew to play a large role in student life, with many chapters becoming a part of national organizations. As of 1952, 19 fraternities had national restrictions based on race, religion or national origin, and of the 32 fraternities without such national requirements, 19 did not have "mixed" memberships. In response, the undergraduate Interfraternity Council passed a resolution condemning discrimination.[51][52] In the 1960s, the Trustees established a Commission to examine the membership restrictions of those national organizations. Cornell adopted a policy that required fraternities and sororities affiliated with nationals that discriminated based on religion or race to either amend their national charters or quit the national organizations. As a result, a number of national Greek organizations dropped racial or religious barriers to their membership.[53]

In 1873, the cornerstone of Sage Hall was laid. This new hall was to house the Sage College for Women and thus to concretely establish Cornell University's coeducational status.[54] Ezra Cornell wrote a letter for posterity—dated May 15, 1873—and sealed it into the cornerstone. No copies of the letter were made, and Cornell kept its contents a secret. However, he hinted at the theme of the letter during his speech at the dedication of Sage Hall, stating that "the letter deposited in the cornerstone addressed to the future man and woman, of which I have kept no copy, will relate to future generations the cause of the failure of this experiment, if it ever does fail, as I trust in God it never will."[54]

Cornell historians largely assumed that the "experiment" to which Cornell referred was that of coeducation, given that Sage Hall was to be a women's dormitory and that coeducation was still a controversial issue at the time.[54] However, when the letter was finally unearthed in 1997, its focus was revealed to be the university's nonsectarian status—a principle which had invited equal controversy in the 19th century, given that most universities of the time had specific religious affiliations. Cornell wrote:

On the occasion of laying the cornerstone of the Sage College for women of Cornell University, I desire to say that the principle [sic] danger, and I say almost the only danger I see in the future to be encountered by the friends of education, and by all lovers of true liberty is that which may arise from sectarian strife.

From these halls, sectarianism must be forever excluded, all students must be left free to worship God, as their concience [sic] shall dictate, and all persons of any creed or all creeds must find free and easy access, and a hearty and equal welcome, to the educational facilities possessed by the Cornell University.

Coeducation of the sexes and entire freedom from sectarian or political preferences is the only proper and safe way for providing an education that shall meet the wants of the future and carry out the founders' idea of an Institution where "any person can find instruction in any study." I herewith commit this great trust to your care.[55]

Infrastructure innovations

[edit]Between 1872 and 1875, the university's first professor of physics William Arnold Anthony and student George S Moler (later, a professor at Cornell) installed two electric arc lamps on campus, one of which was in the Sage Chapel tower.[56] The set-up represented many firsts, the first dynamo and outdoor electric lighting in the United States, and the world's first underground electricity distribution system.[57] It was said to be the "first locality in America, if not the world, to have a permanent installation of electric arc lamps."[56] The lamps were "visible for many miles around, and it excited the wonder of the inhabitants."[58][56]

In 1883, Cornell was one of the first university campuses to use electricity to light the grounds from a water-powered dynamo.[59] In 1904, a hydroelectric plant was built in the Fall Creek gorge. The plant takes water from Beebe Lake through a tunnel in the side of the gorge to power up to 1.9 megawatts of electricity. The plant continued to serve the campus's electric needs until 1970, when local utility rates placed a heavy economic penalty on independently generating electricity. The abandoned plant was vandalized in 1972, but renovated and placed back into service in 1981.[60]

In 1986–87, a cogeneration facility was added to the central heating plant to generate electricity from the plant's waste heat.[59] A Cornell Combined Heat & Power Project, which was completed in December 2009, shifted the central heating plant from using coal to natural gas and enable the plant to generate all of the campus's non-peak electric requirements.[61]

In the 1880s, a suspension bridge was built across Fall Creek to provide pedestrian access to the campus from the North. In 1913, Professors S.C. Hollister and William McGuire designed a new suspension bridge that is 138 ft (42 m), 3.5 in. above the water and 500 ft (150 m) downstream from the original. However, the second bridge was declared unsafe and closed August 1960 to be rebuilt with a replacement of the same design.[62]

The Arecibo Observatory, radio and radar telescope, from its construction in the 1960s until 2011, was managed by Cornell University.[63][64][65]

Cornell began operating a closed loop, central chilled water system for air conditioning and laboratory cooling in the 1963 using centralized mechanical chillers, rather than inefficient, building-specific air conditioners.[66] In 2000, Cornell began operation of its Lake Source Cooling System which uses the cold water temperature at the bottom of Cayuga Lake (approx 39 °F) to air condition the campus.[67] The system was the first wide-scale use of lake source cooling in North America.

Giving and alumni involvement

[edit]The first endowed chair at Cornell was the Professorship of Hebrew and Oriental Literature and History donated by New York City financier Joseph Seligman in 1874,[68] with the proviso that he (Seligman) would nominate the chairholder; and following his wishes, Dr. Felix Adler (Society for Ethical Culture), was appointed. After two years, Professor Adler was quietly let go. Seligman demanded an inquiry. On rebuffing Joseph Seligman in 1877, the trustees established one of their guiding principles governing the receipt of gifts, "That in the future no Endowment of Professorships will be accepted by the (Cornell) University which deprives the Board of Trustees of the power to Select The persons who shall fill such professorships".[69]

In September 1896, Cornell's president Jacob Gould Schurman prevailed upon the board of trustees to extend an offer to Nathaniel Schmidt. The situation at Colgate's Divinity School had deteriorated. Schmidt's unorthodox theology generated discomfort within that college. From 1886 to the arrival of Professor Nathaniel Schmidt in 1896, Cornell's Library maintained its support for the acquisition of Near Eastern materials. Taking over as Cornell President, Jacob Gould Schurman decided Cornell needed a chair of Hebrew language. In 1896, Schurman persuaded Henry W. Sage to finance a professor of Semitic Languages and Literatures for AY1896-97 and AY 1897-98. He knew the university could secure Schmidt at a bargain. Schmidt's unorthodox theological views made his stay at Colgate Divinity School untenable. Schmidt gained the respect of the Cornell community. Noted for his personal and scholarly integrity, he was soon shielded by sympathetic administrators. Schmidt served Cornell for thirty-six years, carrying a high teaching load in addition to this extensive research. He taught an elementary course in Hebrew each year. Advanced Hebrew covered the leading writers of the Old Testament and some parts of the Mishnaic and other Talmudic literature in three years. General linguistics students were advised to begin their study of Semitic languages with Arabic, also offered each year. Aramaic and Egyptian alternated with Assyrian and Ethiopic. The Semitic Seminary, given one term each year, was dedicated to epigraphical studies.

The second was the Susan E. Linn Sage Professor of Ethics and Philosophy given in 1890 by Henry W. Sage. Since then, 327 named professorships have been established, of which 43 are honorary and do not have endowments. The university's first endowed scholarship was established in 1892.[70]

The original University charter adopted by the New York State legislature required that Cornell give scholarships from students in each legislative district to attend the university tuition-free.[71] Although both Cornell and White believed this meant one scholarship, the legislature later argued that it meant one new freshman student per district each year, or four per district.[72] This allowed students of diverse financial resources to attend the university from the start.

When Atlantic Gulf & Pacific Dredging Company President John McMullen left his estate to Cornell to establish scholarships for engineering students, Cornell's trustees decided to invest those funds and eventually sold the dredging company. The resulting fund is Cornell's largest single scholarship endowment. Since 1925, the fund has provided substantial assistance to more than 3,700 engineering students.[73] (Cornell has received a number of unusual non-cash (in-kind) gifts over the years, including: Ezra Cornell's farm, the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory (see below), a copy of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, a Peruvian mummy, and the Ostrander elm trees.)[74]

Before the university opened, the State Legislature amended Cornell's charter on April 24, 1867 to specify alumni elected trustees.[75] However that provision did not become operative until there were at least 100 alumni[76] in 1872.[77] Cornell was one of the first Universities to elect trustees by direct election.[78] (Harvard was probably the first to shift to direct election of its Board of Overseers by alumni in 1865.) Cornell's first female trustee was Martha Carey Thomas (class of 1877), who the alumni elected while she was serving as President of Bryn Mawr College.[79]

In October 1890, Andrew Carnegie became a Cornell Trustee and quickly became aware of the lack of an adequate pension plans for Cornell faculty. His concern led to the formation in 1905 of what is now called Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAA).[80] In October 2010, David A. Atkinson and his wife Patricia donated $80 million to fund a sustainability center, and the gift is currently the largest single gift to Cornell (ignoring inflation) and is the largest ever given to a university for sustainability research and faculty support.[81][82][83][84]

Many alumni classes elected secretaries to maintain correspondence with classmates. In 1905, the Class Secretaries organized to form what is now called the Cornell Association of Class Officers, which meets annually to develop alumni class programs and assist in organizing reunions. The Cornell Alumni News is an independent, alumni-owned publication founded in 1899[85] It is owned and controlled by the Cornell Alumni Association, a separate nonprofit corporation and is now known as Cornell Alumni Magazine.

Support from New York State

[edit]Under the Morrill Act, states were obligated to fund the maintenance of land grant college facilities, but were not obligated to fund operations. Subsequent laws required states to match federal funds for agricultural research stations and cooperative extension. In his inaugural address as Cornell's third president on November 11, 1892, Jacob Gould Schurman announced his intention to enlist the financial support of the state.[86] Until that point, Cornell's relationship with the state was a net economic loss. Cornell was offering full scholarships to four students in each New York assembly district every year and was spending funds to serve as the state's land-grant university. It determined to convince the state to become a benefactor of the university, instead. In 1894, the state legislature voted to give financial support for the establishment of the New York State College of Veterinary Medicine and to make annual appropriations for the college.[87] This set the precedents of privately controlled, state-supported statutory colleges and cooperation between Cornell and the state. The annual state appropriations were later extended to agriculture, home economics, and following World War II, industrial and labor relations.

In 1882, Cornell opened the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station in Geneva, New York, the sixth oldest institution of its kind in the United States.[88] It made significant advances in scientific agriculture and for many years played an active role in agriculture law enforcement.

In 1900, a home economics curriculum was added to Cornell's Agriculture college. This was expanded to a separate state-supported school in 1919.[89] The Home Economics School, in turn, began to develop classes in hotel administration in 1922, which spun off into a separate, endowed college in 1950.[90]

In 1898, the New York State College of Forestry opened at Cornell, which was the first forestry college in North America.[91] The college undertook to establish a 30,000-acre (120 km2) demonstration forest in the Adirondacks, funded by New York State.[92] However, the plans of the school's director Bernhard Fernow for the land drew criticism from neighbors living on Saranac Lake, Knollwood Club, and Governor Benjamin B. Odell vetoed the 1903 appropriation for the school.[93] In response, Cornell closed the school.[94] By some reports, Cornell gained annual state funding of the College of Agriculture in exchange for closing the forestry college.[95] Subsequently, in 1911, the State Legislature established a New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse University,[96] and the remains of Cornell's program became the Department of Natural Resources in its Agriculture College in 1910.[91] However, Cornell had contracted with the Brooklyn Cooperage Company to take the logs from the forest, and the People of the State of New York, Knollwood Club members ("People v. the Brooklyn Cooperage Company and Cornell") sued to stop the destructive practices of Fernow even before the closing of the school.[97] Cornell University lost the case in 1910 and on appeal in 1912. Cornell eventually established a research forest south of Ithaca, the Arnot Woods. When New York State later funded the construction of a Forestry building for the Agriculture school, New York State College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Cornell named it Fernow Hall.

In 1914, the US Department of Agriculture began to fund cooperative extension services through the land-grant college of each state, and Cornell expanded its impact by sending agents to spread knowledge in each county of New York State. Although Syracuse had started awarding forestry degrees at this point, Cornell's extension agents covered all of home economics and agriculture, including forestry.

In 1945, the New York State Legislature founded the New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell, in response to requests from organized labor and Democratic leaders.[98] The school quickly gained national stature when U.S. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, who was the first female US Cabinet member and served longer than anyone else as Secretary of Labor (12 years), joined the ILR faculty. Since agricultural interests were mostly affiliated with the Republicans, Cornell enjoyed bi-partisan support following World War II.

In 1948, the Legislature placed all state-funded higher education into the new State University of New York (SUNY). Cornell's four statutory colleges (agriculture, human ecology, labor relations and veterinary medicine) have been affiliated with SUNY since its inception, but did not have any such state affiliation prior to that time. Statutory college employees legally are employees of Cornell, not employees of SUNY. The State Education Law gives SUNY's board of trustees the authority to approve Cornell's appointment of the deans/unit heads of the statutory colleges, and control of the level of state funding for the statutory colleges.[99]

Today, state support is significant. In 2007–08, Cornell received a total of $174 million of state appropriations for operations.[100] Of the $2.5 billion in capital spending budgeted for 2007–2017, $721 million was to come from the state of New York.[101]

Medical education

[edit]Starting in 1878, Cornell's Ithaca campus offered a pre-medical school curriculum, although most medical students enrolled in medical school directly after high school.[102] In 1896, three New York City institutions, the University Medical College, the Loomis Laboratory and the Bellevue Hospital Medical College united with the goal of affiliating with New York University (NYU). Unfortunately, NYU imposed a number of surprising new policies including limiting faculty to what they would have otherwise earned in private practice.[103] The faculty revolted in 1897 and sought the return of the property of the three former institutions, with a resulting lawsuit. On March 22, 1904 and April 5, 1904, the New York State Court of Appeals ordered NYU to return property to Loomis Laboratory because the NYU Dean had breached oral promises made to form the merger.[104] Having won their separation from NYU, the medical faculties sought a new university affiliation, and on April 14, 1898, Cornell's board of trustees voted to create a medical school and elected former NYU professors as its dean and faculty.[105] The school opened on October 4, 1898 in the Loomis Laboratory facilities. In 1900, a new campus on First Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan opened which was donated by Oliver Hazard Payne.[105] Cornell also began a program in the fall of 1898 to allow students to take their first two years of medical school in Ithaca, with Stimson Hall being constructed to house that program. The building opened in 1903.[106] The M.D. degree program was open to both men and women, but women were required to study in Ithaca for their first two years.[107] In 1908, Cornell was one of the early medical schools to require an undergraduate degree as a prerequisite to admission to the M.D. program.[108] In 1913, Cornell's medical school affiliated with New York Hospital as its teaching hospital.[108] Unlike the New York branch of the medical school which was well endowed, the Ithaca branch was subsidized by the university, and the Trustees reduced its scope to just first year students in 1910, and eventually phased it out.[109]

In 1927, William Payne Whitney's $27 million donation led to the building of the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic, which became the name for Weill Cornell's large psychiatric effort. That same year, the college became affiliated with New York Hospital and the two institutions moved to their current joint campus in 1932. The hospital's Training School for Nurses became affiliated with the university in 1942, operating as the Cornell Nursing School until it closed in 1979.[110]

In 1998, Cornell University Medical College's affiliate hospital, New York Hospital, merged with Presbyterian Hospital (the affiliate hospital for Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons). The combined institution operates today as NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. Despite the clinical alliance, the faculty and instructional functions of the Cornell and Columbia units remain distinct and independent. Multiple fellowships and clinical programs have merged, however, and the institutions are continuing in their efforts to bring together departments, which could enhance academic efforts, reduce costs, and increase public recognition. All hospitals in the NewYork-Presbyterian Healthcare System are affiliated with one of the two colleges.

Also in 1998, the medical college was renamed as Weill Medical College of Cornell University after receiving a substantial endowment from Sanford I. Weill, then Chairman of Citigroup.[110]

Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory

[edit]Curtiss-Wright built this lab facility located in the suburbs of Buffalo, New York as a part of the World War II effort. As a part of its tax planning in the wake of the war effort, Curtiss-Wright donated the facility to Cornell University to operate "as a public trust" and received a charitable tax deduction.[111] Seven other east coast aircraft companies also donated $675,000 to provide working capital for the lab.[112] The lab operated under the name Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory from 1946 until 1972. During this same time, Cornell formed a new Graduate School of Aerospace Engineering on its Ithaca, New York campus.

CAL invented the first crash test dummy in 1948, the automotive seat belt in 1951, the first mobile field unit with Doppler weather radar for weather-tracking in 1956, the first accurate airborne simulation of another aircraft (the North American X-15) in 1960, the first successful demonstration of an automatic terrain-following radar system in 1964, the first use of a laser beam to successfully measure gas density in 1966, the first independent HYGE sled test facility to evaluate automotive restraint systems in 1967, the mytron, an instrument for research on neuromuscular behavior and disorders in 1969, and the prototype for the Federal Bureau of Investigation's fingerprint reading system in 1972. CAL served as an "honest broker" making objective comparisons of competing plans to build military hardware.[113] It also conducted classified counter-insurgency research in Thailand for the Defense Department.[113] By the time of its divestiture, CAL had 1,600 employees.[113] CAL conducted wind tunnel test on models of a number of skyscraper buildings, including most notably the John Hancock Tower in Boston, Massachusetts and the 40-story Commerce House in Seattle, Washington.[114]

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, universities came under criticism for conducting war-related research particularly as the Vietnam War became unpopular, and Cornell University tried to sever its ties. Cornell accepted a $25,000,000 offer from EDP Technology, Inc. to purchase the lab in 1968.[113] However, a group of lab employees who had made a competing $15,000,000 offer organized a lawsuit to block the sale. In May 1971, New York's highest court ruled that Cornell had the right to sell the lab.[115] At the conclusion of the suit, EDP Technology could not raise the money, and in 1972, Cornell reorganized the lab as the for-profit Calspan Corporation and then sold its stock in Calspan to the public.[116]

Race relations

[edit]Cornell had enrolled African-American students by the mid-1880s.[117] On December 4, 1906, Alpha Phi Alpha, the first Greek letter fraternity for African-Americans was founded at Cornell.[118] Cornell had a very low black enrollment until the 1960s, when it formed the Committee on Special Educational Projects (COSEP) to recruit and mentor minority students. In 1969, Cornell established its Africana Studies and Research Center, one of the first such black studies programs in the Ivy League.[119] On April 1, 1970, during a period of heightened racial tension, the building that housed the Africana Studies center burned down.[120] Since 1972, Ujamaa, a special interest program dormitory located in North Campus Low Rise No. 10, provides housing for many non-white students.[121] However, in 1974, the New York State Board of Regents ordered it desegregated, and its status remained controversial for years.[122][123]

Willard Straight Hall Takeover

[edit]

On April 19, 1969, during a parents' weekend, over 80 members of Cornell's Afro-American Society took over the student union building, Willard Straight Hall. The takeover was precipitated by increasing racial tension at the university and the students' frustration with the administration's lack of support for a black studies program. The specific catalysts for the takeover were a reprimand of three black students for an incident the previous December[124] and a cross burning in front of the black women's cooperative and other cases of racism.[125][126]

By the following day a deal was brokered between the students and university officials, and on April 20, the takeover ended, with the administration ceding to some of the Afro-American Society's demands. The students emerged making a black-power salute and with guns in hand (the guns had been brought into Willard Straight Hall after the initial takeover). James A. Perkins, president of Cornell during the events, resigned soon after the crisis.

Some of the elements of the deal required faculty approval, and the faculty voted to uphold the reprimands of the three students on April 21.[127] The faculty was asked to reconsider, and a group of 2,000[128] to 10,000 gathered in Barton Hall to debate the matter as the faculty deliberated.[129] This "Barton Hall Community" formed a representative Constituent Assembly which undertook a comprehensive review of the university. Among the changes stemming from the crisis were the founding of an Africana Studies and Research Center, overhaul of the campus governance and judicial system, and the addition of students to Cornell's board of trustees. The crisis also prompted New York to enact the Henderson Law requiring every college in the state to adopt rules for the maintenance of public order.[130]

Historian Donald Kagan was a professor at Cornell from 1958 to 1969 and left Cornell due to the takeover. Kagan was once a liberal democrat, but his views changed after the takeover and became one of the original signers to the 1997 Statement of Principles by the neoconservative think tank Project for the New American Century.[131] According to Jim Lobe,[132] Kagan's turn away from liberalism occurred in 1969 when Cornell University was pressured into starting a "Black Studies" program by gun-wielding students seizing Willard Straight Hall on campus: "Watching administrators demonstrate all the courage of Neville Chamberlain had a great impact on me, and I became much more conservative."

Former Cornell Professor Thomas Sowell also left Cornell over the takeover. Sowell characterized the students as "hoodlums" with "serious academic problems [and] admitted under lower academic standards" and noted "it so happens that the pervasive racism that black students supposedly encountered at every turn on campus and in town was not apparent to me during the four years that I taught at Cornell and lived in Ithaca."[133]

Interdisciplinary studies

[edit]Historically, Cornell's colleges have operated with great autonomy, each with a separate admissions policy, separate faculty, separate fundraising staff and in many cases, separate tuition structure. However, the university has taken steps to encourage collaboration between related academic fields within the university and with outside organizations. In the 1960s, the university created a Division of Biological Sciences to unify related programs in the Art and Agriculture colleges. Although a success, the structure was ultimately dropped in 1999 due to difficulty with funding.[134][135]

The Faculty of Computing and Information Science was established in 1999 to unify computer science efforts throughout the university. Students still enrolled in one of the existing colleges. For its first ten years, Robert Constable served as its dean.[136] In 2020, it became the Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science.[137]

Affordability and use of the endowment

[edit]Since the 1970s, tuition at Cornell and other Ivy League schools has grown much faster than inflation. This trend coincided with the creation of Federally guaranteed student loan programs. At the same time, the endowments of these schools continue to grow due to gifts and successful investments. Critics called for universities to keep their tuition at affordable levels and to not hoard endowment earnings.[138][139] As a result, in 2008, Cornell and other Ivy Schools decided to increase the spending of endowment earnings in order to subsidize tuition for low and middle income families, reducing the amount of debt that Cornell students will incur.[140][141] Cornell also placed a priority to soliciting endowed scholarships for undergraduates.[142] In fall 2007, Cornell had 1,863 undergraduates (14% of all undergraduates) receiving federal Pell Grants. Cornell's Pell Grant students roughly totals the combined Pell Grant recipients studying at Harvard, Princeton and Yale.[143]

COVID-19 Pandemic

[edit]On March 10, 2020, Cornell announced that all classes were moving to virtual instruction for the rest of the spring semester.[144] Research facilities reopened in late May,[145] and classes in the Fall 2020 semester were a mix of virtual and in-person.[146] Cornell held a virtual graduation event for the Class of 2020 on June 13, 2021,[147] and an in-person event on September 19, 2021.[148]

In June 2021, Cornell announced that the Fall 2021 semester would be fully in-person provided cases remained low;[149] in December 2021, Cornell moved all classes online at its Ithaca campus in response to a surge in positive cases and detection of the omicron variant.[150]

Vaccine Mandate

[edit]Following the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines in the United States, Cornell mandated all students be fully vaccinated by December 15, 2021,[151] and all faculty and staff by January 18, 2022 (pushed back from an initial deadline of December 15).[152]

Portrayal in fiction

[edit]Students and faculty have chronicled Cornell in works of fiction. The most notable was The Widening Stain which first appeared anonymously.[153] It was since revealed to have been written by Morris Bishop.[154] Alison Lurie wrote a fictional account of the campus during the Vietnam War protests called The War Between the Tates.[155] Matt Ruff captured Cornell around 1985 in The Fool on the Hill.[156] Richard Fariña wrote a novel based on a real 1958 protest led by Kirkpatrick Sale against in loco parentis policies in Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me.[157] Steve Thayer takes his readers to the Cornell campus in Ithaca Falls,[158] a mystery thriller about a Cornell criminologist who travels back to 1929 in pursuit of a serial killer. Ed Helms' character Andrew Bernard of the TV show The Office was an alumnus of Cornell University. Shantanu Naidu also portrayed it in his book I came upon a lighthouse. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Came_Upon_a_Lighthouse

See also

[edit]- For the history of the Ithaca campus, see:

- Cornell Central Campus

- Cornell North Campus

- Cornell West Campus

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wright, Albert Hazen (1960). Cornell's Three Precursors. I. New York Central College. Pre-Cornell and Early Cornell, Volume 8. Studies in History. Cornell University.

- ^ Wright, Albert Hazen (1957). Cornell's three precursors: II. New York State Agricultural College. Pre-Cornell and Early Cornell, Volume 6. Studies in History. New York State College of Agriculture, at Cornell University.

- ^ Wright, Albert Hazen (1958). Cornell's three precursors: III. New York People's College. Pre-Cornell and Early Cornell, Volume 7. Studies in History. Cornell University.

- ^ 7 U.S.C. § 304

- ^ Becker, Carl (1943). Cornell University: Founders and Founding. Cornell University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8014-7615-0.

- ^ Becker, Carl (1943). Cornell University: Founders and Founding. Cornell University Press. p. 62.

- ^ White, Andrew Dickson (March 1905). "II: Yale and Europe—1850-1857". Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White – Volume 1. New York City: The Century Co. – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "Legacy of Leadership – Cornell's Presidents". Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections - Cornell University Library. Archived from the original on March 1, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f White, Andrew Dickson (March 1905). "XVII: Evolution of "The Cornell Idea" — 1850-1865". Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White – Volume 1. New York City: The Century Co. – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Becker, op. cit. p. 82.

- ^ Lang, Daniel W. (Autumn 1978). "The People's College, The Mechanics' Mutual Protection and the Agricultural College Act". History of Education Quarterly. 18 (3): 295–321. doi:10.2307/368090. JSTOR 368090. S2CID 144703424.

- ^ Selkreg, John H. (1894). Landmarks of Tompkins County, New York. D. Mason & Co. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ "The State Agricultural College.; Laying the Corner-stone—Speeches of Ex-Governor King and Others". The New York Times. July 11, 1859. p. 1. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ White, Andrew Dickson (March 1905). "XIX: Organization of Cornell University— 1865-1868". Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White – Volume 1. New York City: The Century Co. – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Becker, Carl (1943). Cornell University: Founders and Founding. Cornell University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8014-7615-0.. See also Section 5 of the Cornell charter.

- ^ "An Act to establish the Cornell University…". Laws of New York. Vol. 88th sess. 1865. pp. 1188–1194. hdl:2027/nyp.33433090742218. ISSN 0892-287X.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) Chapter 585, enacted 27 April 1865. - ^ White, Andrew Dickson (March 1905). "XX: The First Years of Cornell University—1868-1870". Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White – Volume 1. New York City: The Century Co. – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ a b Becker, Carl (1943). Cornell University: Founders and Founding. Cornell University Press. p. 131.

- ^ "2009–10 Factbook" (PDF). Cornell University. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ "The Cornell Public Library". Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections - Cornell University Library. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ "3001-Cascadilla Hall Facility Information". Cornell University. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ "Charles William Eliot – History". Harvard University. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ Quoted in Rhodes, Frank H. T. (2001). The Creation of the Future: The Role of the American University. Cornell University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8014-3937-7.

- ^ Becker, Carl (1943). Cornell University: Founders and Founding. Cornell University Press. p. 88.

- ^ Whalen, Michael L. (May 2003). "2003-04 Financial Plan: Gifts and Giving" (PDF). Cornell University Division of Planning & Budget. Retrieved July 25, 2006.

- ^ a b "Cornell Loses a Legacy: Decision Against the University in the Fisk Suit. The Highest Court Holds that it Cannot Receive the Gift – A Big Fee For David B. Hill". The New York Times. May 20, 1890. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ Malkiel, Nancy Weiss (2016). 'Keep the damned women out': The Struggle for Coeducation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17299-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Conable, Charlotte Williams (1977). Women at Cornell: The Myth of Equal Education. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9167-3.

- ^ "Our History". Cornell University Graduate School. Archived from the original on April 10, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ "3002-Sage Hall Facility Information". Cornell University Facilities and Campus Services. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "College View of the Day: "Cornell University" Richard Rummell (1848-1924)". Graham Arader. July 15, 2011.

- ^ "The legacy of Cornell home economics". Cornell Chronicle. Cornell University. April 7, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c Loebenstein, Barbara (April 16, 1955). "University Co-Eds Traced from 1871 to 1955". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 71. p. 21. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ Steinberg, Julie (September 16, 1980). "Female Students Work For Equal Treatment". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 97, no. 14. p. 34. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ Fogle, H. William Jr (July 10, 2010). "∆X of ∆KE Research Note #06: Anti-coedism Philosophy and Mores". Cornell University Archives.

- ^ "Not Looked Upon with Favor by the Young Men of the University Have Few Interests in Common Male Students Do Not Regard the 'Co-eds' as Their Equals Socially". New York Herald. June 24, 1894. p. 4:1.

- ^ "A Woman Poet". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 55, no. 128. March 21, 1935.

- ^ "The Last Stand". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 56, no. 82. January 14, 1936.

- ^ "Balch Hall". Cornell University Campus Life. Archived from the original on January 27, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Housing – Lyon Hall". Cornell University. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ^ "History and Archives". Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. August 26, 2011. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Donald F. (December 1, 2010). "Admission of Women to Veterinary Medicine at Cornell". Veterinary Legacy. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ Becker op. cit. at 7–14.

- ^ a b "Sage Chapel". Cornell University. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ New York State Education Law §5702.

- ^ "Chaplains". Cornell University Student & Campus Life. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ Zaroulis, Nancy & Sullivan, Gerald (1989). Who Spoke Up? American Protest Against the War in Vietnam 1963–1975. Horizon Book Promotions. ISBN 978-0-385-17547-0.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2002) [1994]. You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 126–138. ISBN 978-0-8070-7127-4.

- ^ Lang, Susan (October 31, 2006). "Cornell's CRESP transforms its name to reflect new model for social change". Cornell Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 11, 2007. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ "History". Center for Jewish Living at Cornell. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ "Proposed IFC Resolution". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 68, no. 143. April 9, 1952. p. 4. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ "IFC Passes Proposals Against Bias Clauses". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 68, no. 165. May 5, 1952. p. 1. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ Huffman, Deborah (February 23, 1968). "Trustees Implement Anti-Bias Legislation for All Living Units". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 84, no. 92. p. 1. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ a b c Goetz, Jill (March 20, 1997). "Ezra Cornell's commitment to nonsectarianism". Cornell Chronicle. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ^ "Sage Cornerstone Letter". Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections - Cornell University Library. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c Guide to the campus: Cornell University. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University. 1920. p. 53. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ Bishop, Morris (October 31, 1962). A History of Cornell. Cornell University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-80140-036-0.

- ^ Waterman, Thomas Hewett (1905). Cornell University, A History: Volume 2. The University publishing society. p. 153. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Early History of District Energy at Cornell University". Cornell University Utilities and Energy Management. Archived from the original on July 4, 2007. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ "Hydroelectric Plant". Cornell University Utilities and Energy Management. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ Steele, Bill (January 18, 2010). "CU moves beyond coal with opening of new power plan". Cornell Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Suspension Bridge". Cornell University Alumni. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ Altschuler, Daniel R. (2002). "The National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center's (NAIC) Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico" (PDF). Single–Dish Radio Astronomy: Techniques and Applications. ASP Conference Series. 278. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Lalonde, L. M. (October 18, 1974). "The Upgraded Arecibo Observatory". Science. 186 (4160): 213–218. Bibcode:1974Sci...186..213L. doi:10.1126/science.186.4160.213. PMID 17782009. S2CID 43353056.

- ^ Butrica, Andrew (November 28, 1994). "The History of the Arecibo Observatory: Interview with Dr. William Gordon". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012.

- ^ "Cooling – Chilled Water Plants". Cornell University Utilities and Energy Management. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ "Lake Source Cooling: An Idea Whose Time Has Come". Cornell University Utilities and Energy Management. Archived from the original on April 26, 2005. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ "Commencement Season.; Cornell University. The Sixth Annual Commencement Address of Prof. Felix Adler" (PDF). The New York Times. July 1, 1874. p. 5. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ Whalen, Michael L. (May 2003). "2003-04 Financial Plan: Gifts and Giving" (PDF). Cornell University Division of Planning & Budget. p. 12. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Whalen, Michael L. (May 2003). "2003-04 Financial Plan: Gifts and Giving" (PDF). Cornell University Division of Planning & Budget. p. 13. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ^ Becker, Carl (1943). Cornell University: Founders and Founding. Cornell University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8014-7615-0.

- ^ Becker, Carl L. (1943). Cornell University: Founders and the Founding. Cornell University Press. pp. 93–94. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ^ "John McMullen Schoarships". Cornell University Gift Guide. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ^ Whalen, Michael L. (May 2003). "2003-04 Financial Plan: Gifts and Giving" (PDF). Cornell University Division of Planning & Budget. p. 14. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ^ Hewett, Waterman Thomas; Holmes, Frank R. & Williams, Lewis A. (1905). Cornell University, A History, Volume 1. University Publishing Society. p. 278. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ The revised statutes of the State of New York. Banks & Brothers. 1881. p. 537. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ Kasson (at 109); Whalen (at 15) says the first election was in 1874.

- ^ Ranck, Samuel H. (October 1901). "Alumni Representation In College Government". Education. 22 (2). Boston: New England Publishing Company: 108–109. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ Whalen at 15.

- ^ Cornell Financial Plan, May 2007, p. 32.

- ^ "Record Gift to Cornell to Fund Research". The Wall Street Journal. October 28, 2010. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- ^ Linhorst, Michael (October 29, 2010). "Atkinson '60 Gives $80 Million to Fund Center for a Sustainable Future". The Cornell Daily Sun. Archived from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "Graduate Pays Back Cornell With $80 Million Gift". The New York Times. October 28, 2010.

- ^ "Cornell University gets $80 million gift for sustainability work". Syracuse.com. Associated Press. October 28, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Massi, Joseph (September 7, 1971). "Trustees Seek Clear 'Alumni News' Policy". The Cornell Daily Sun. p. 1. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ "Inaugurating the Presidents: Jacob Gould Schurman, 1892". Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections - Cornell University Library. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ "History and Archives". Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. Archived from the original on June 14, 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "History of the Experiment Station". New York State Agricultural Experiment Station. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ "History". Cornell University College of Human Ecology. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ "History". Cornell University School of Hotel Administration. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Ogelsby, R.T. & Brumsted, H.B. "Department History". Cornell University Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on October 7, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ Donaldson, Alfred Lee (1921). A History of the Adirondacks, Volume 2. The Century Co. pp. 202–207. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ Fuller, R.H. (1906). "The Struggles of the First State to Preserve its Forests". Appleton's Magazine. Vol. 8. p. 613. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "Cornll School of Forestry Suspended.; Action Followed Failure of State to Provide Means for Its Support". The New York Times. June 18, 1903. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ^ Colman, Gould P. (1963). Education & Agriculture, A History of the NYS College of Agriculture at Cornell University. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 162.

- ^ "Exhibits – "SUNY ESF and SU: 100 Years of Collaboration"". Syracuse University Archives. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "Cornell Forestry Case.; Appellate Division Decision Against Brooklyn Cooperage Company". The New York Times. July 13, 1906. p. 4. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ^ "A Brief History of ILR". Cornell University ILR School. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ N.Y.S. Education Law § 355(g).

- ^ Cornell Financial Plan, May 2007, p. 75.

- ^ Cornell Financial Plan, May 2007, p. 65.

- ^ Bishop, Morris (1962). A History of Cornell. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-8014-0036-0.

- ^ Bishop, op cit. p. 318

- ^ Bishop, op cit. p. 319

- ^ a b Bishop, op cit. p. 320

- ^ Bishop, op cit. p. 388

- ^ Bishop, op cit. p. 321

- ^ a b Bishop, op cit. p. 385

- ^ Bishop, op cit. p. 389

- ^ a b "Our years of achievement". Weill Medical College. Archived from the original on July 13, 2006. Retrieved July 6, 2006.

- ^ "Curtiss-Wright Corp. Gives Lab to Cornell; To Aid Air Research". The Cornell Daily Sun. December 21, 1945. p. 2. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ "Aircraft Companies Donate Gift To Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory". The Cornell Daily Sun. February 15, 1946. p. 2. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Zuckerman, Edward (September 18, 1968). "Trustees Accept Firm's Offer of $25M for CAL Purchase". The Cornell Daily Sun. p. 1. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ Gannon, Robert (October 1975). "Wind Engineering". Popular Science. p. 84. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "Court Ruling Okays Planned Sale of CAL". The Cornell Daily Sun. May 13, 1971. p. 1. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ Sennet, Charles (January 29, 1973). "New Projects Adopted; Stock Price Falls". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 89, no. 77. p. 1. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ Walter, Marcus (October 23, 2009). "Historian: Early black students were 'part and apart' at CU". Cornell Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 1, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ "A Brief History of Alpha Phi Alpha". Northwestern University. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Crawford, Franklin (May 4, 2005). "Africana Studies and Research Center is on the ascendant". Cornell News Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Pre-Dawn fire destroys Africana Studies Center" (PDF). Cornell Chronicle. Vol. 1, no. 24. April 5, 1970. p. 1. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ "3210-Ujamaa Resid Coll Low Rise 10 Facility Information". Cornell University Facilities and Campus Services. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Linder, Barbara (February 19, 1974). "Desegregation Order Rejected by Ujamaa". Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 90, no. 88. p. 3. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

- ^ "Ujamaa Receives Bombing Threats". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 97, no. 144. May 27, 1981. p. 2. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

- ^ Warshauer, Richard & Goldman, Mark (April 18, 1969). "Board Reprimands 3 Blacks, Gives No Penalties to Two". The Cornell Daily Sun. p. 1. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ Downs, Donald Alexander (1999). Cornell '69: Liberalism and the Crisis of the American University. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-80143-653-6.

- ^ Reppert, Barton (April 20, 1969). "Day Hall, Faculty consider official response". The Cornell Daily Sun. p. 1. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ Mills, Betty & Warshauer, Richard (April 22, 1969). "Faculty Takes Controversial Stand". The Cornell Daily Sun. p. 1. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ Neubauer, Richard (April 24, 1969). "Perkins Cheered by Barton Throng After Faculty Drops Penalties". The Cornell Daily Sun. p. 1. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ Mann, Ronnie & Neubauer, Richard (April 25, 1969). "5,000 Attend Barton Teach-in on Racism". The Cornell Daily Sun. p. 1. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ Warshauer, Richard (September 10, 1969). "New Regulations Approved". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 86, no. 1. p. 1. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "Statement of Principles". Project for the New American Century. June 3, 1997. Archived from the original on February 5, 2005. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ cited in The Fall of the House of Bush by Craig Unger, p. 39, n.

- ^ Sowell, Thomas (October 30, 1999). "The Day Cornell Died". Hoover Institution. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ Foote, R. H. (October 21, 1998). "Comments on the Division of Biological Sciences" (PDF). Cornell University Faculty. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 19, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Rawlings decides on reorganization for biological sciences". Cornell News Service. November 17, 1998. Archived from the original on April 9, 2005. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Steele, Bill (June 11, 2008). "Robert Constable, founding dean of computing and information science, will step down in 2009". Cornell News Service. Archived from the original on June 18, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Lefkowitz, Melanie (December 17, 2020). "Gift from Ann S. Bowers '59 Creates New College of Computing and Information Science". Cornell Chronicle. Cornell University.

- ^ Coy, Peter (March 1, 2009). "Academic Endowments: The Curse of Hoarded Treasure". Business Week. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

Trustees may solicit funds for endowment rather than current spending simply because they like the idea of presiding over a big pile of money.

- ^ Schworm, Peter (February 28, 2008). "Colleges guard soaring endowments". Boston Globe. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ "Cornell drops need-based loans for students from families earning under $75,000". Cornell Chronicle. January 31, 2008. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ Kelley, Susan (January 29, 2010). "Financial aid offsets tuition increase for neediest students, says provost". Cornell Chronicle. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ Powers, Jacquie (January 28, 1999). "CU announces changes in financial aid policy to enhance affordability". Cornell Chronicle. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ Your Gift Matters, Cornell University, 2009.

- ^ "Cornell announces proactive measures to prevent spread of coronavirus". Cornell University. March 10, 2020.

- ^ Fernandez, Madison (June 2, 2020). "Cornell University reopens research facilities". Ithaca Voice. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Fernandez, Madison (June 30, 2020). "Cornell University students to return to Ithaca in September". Ithaca Voice. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Nutt, David (June 13, 2021). "Virtual Commencement honors 'resilient' Class of 2020". Cornell Chronicle. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Ramanujan, Krishna (September 19, 2021). "Class of 2020 returns for joyful Commencement". Cornell Chronicle. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Butler, Matt (June 28, 2021). "Cornell officially announces that Fall 2021 semester will be fully in-person". The Ithaca Voice. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Stuart, Elizabeth (December 14, 2021). "Cornell University shuts down Ithaca campus after surge of nearly 500 Covid-19 cases detected". CNN. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ "Cornell University Requires Students to Be Vaccinated by Dec. 15, Extends Vaccine Mandate for Faculty & Staff". Erudera College News. November 29, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ Butler, Matt (November 19, 2021). "Cornell pushes back employee COVID-19 vaccine mandate". The Ithaca Voice. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ "Cornellians Blush as Mystery Novel Satirizes Campus; Anonymous Author Hits Faculty, Officers, Architecture". The Cornell Daily Sun. Vol. 62, no. 91. February 2, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved December 16, 2010.

- ^ Bishop, Morris; Bolingbroke Johnson, W. (2007). The Widening Stain. Lyons, CO: Rue Morgue Press. ISBN 978-1-60187-008-7.

- ^ Lurie, Alison (1991) [1974]. The War Between The Tates. New York City: Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-71135-2.

- ^ Ruff, Matt (1988). Fool on the Hill. New York City: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-80213-535-3.

- ^ Fariña, Richard (1996). Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me. New York City: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14018-930-8.

- ^ Thayer, Steve (2015). Ithaca Falls. St. Paul, MN: Conquill Press. ISBN 978-0-9908461-1-6.

Bibliography

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Altschuler, Glenn; Kramnick, Isaac (2014). Cornell: A History, 1940–2015. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-80144-425-8. online

- Becker, Carl L. (1943). Cornell University: Founders and the Founding. Cornell University Press.

- Bishop, Morris (1962). A History of Cornell. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0036-8.

- "History of the Cornell Presidency". Cornell University. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012.

- Downs, Donald Alexander (1999). Cornell '69: Liberalism and the Crisis of the American University. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3653-2. online

- Kammen, Carol (2003). Cornell: Glorious to View. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-935995-03-X. excerpt

- Rudolph, Frederick (1977). Curriculum: A History of the American Undergraduate Course of Study Since 1636. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. ISBN 0-87589-358-9.

- Rudolph, Frederick (1990). The American College and University: A History (2nd ed.). University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-1284-3.

- White, Andrew Dickson (March 1905). Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White – Volume 1. New York City: The Century Co.

- White, Andrew Dickson (March 1905). Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White – Volume 2. New York City: The Century Co.

External links

[edit] Media related to History of Cornell University at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Cornell University at Wikimedia Commons