Fundamental frequency

The fundamental frequency, often referred to simply as the fundamental, is defined as the lowest frequency of a periodic waveform. In music, the fundamental is the musical pitch of a note that is perceived as the lowest partial present. In terms of a superposition of sinusoids, the fundamental frequency is the lowest frequency sinusoidal in the sum of harmonically related frequencies, or the frequency of the difference between adjacent frequencies. In some contexts, the fundamental is usually abbreviated as f0, indicating the lowest frequency counting from zero.[1][2][3] In other contexts, it is more common to abbreviate it as f1, the first harmonic.[4][5][6][7][8] (The second harmonic is then f2 = 2⋅f1, etc. In this context, the zeroth harmonic would be 0 Hz.)

According to Benward's and Saker's Music: In Theory and Practice:[9]

Since the fundamental is the lowest frequency and is also perceived as the loudest, the ear identifies it as the specific pitch of the musical tone [harmonic spectrum].... The individual partials are not heard separately but are blended together by the ear into a single tone.

Explanation

[edit]All sinusoidal and many non-sinusoidal waveforms repeat exactly over time – they are periodic. The period of a waveform is the smallest positive value for which the following is true:

Where is the value of the waveform . This means that the waveform's values over any interval of length is all that is required to describe the waveform completely (for example, by the associated Fourier series). Since any multiple of period also satisfies this definition, the fundamental period is defined as the smallest period over which the function may be described completely. The fundamental frequency is defined as its reciprocal:

When the units of time are seconds, the frequency is in , also known as Hertz.

Fundamental frequency of a pipe

[edit]For a pipe of length with one end closed and the other end open the wavelength of the fundamental harmonic is , as indicated by the first two animations. Hence,

Therefore, using the relation

where is the speed of the wave, the fundamental frequency can be found in terms of the speed of the wave and the length of the pipe:

If the ends of the same pipe are now both closed or both opened, the wavelength of the fundamental harmonic becomes . By the same method as above, the fundamental frequency is found to be

In music

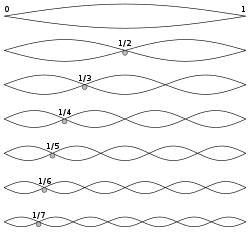

[edit]In music, the fundamental is the musical pitch of a note that is perceived as the lowest partial present. The fundamental may be created by vibration over the full length of a string or air column, or a higher harmonic chosen by the player. The fundamental is one of the harmonics. A harmonic is any member of the harmonic series, an ideal set of frequencies that are positive integer multiples of a common fundamental frequency. The reason a fundamental is also considered a harmonic is because it is 1 times itself.[10]

The fundamental is the frequency at which the entire wave vibrates. Overtones are other sinusoidal components present at frequencies above the fundamental. All of the frequency components that make up the total waveform, including the fundamental and the overtones, are called partials. Together they form the harmonic series. Overtones which are perfect integer multiples of the fundamental are called harmonics. When an overtone is near to being harmonic, but not exact, it is sometimes called a harmonic partial, although they are often referred to simply as harmonics. Sometimes overtones are created that are not anywhere near a harmonic, and are just called partials or inharmonic overtones.

The fundamental frequency is considered the first harmonic and the first partial. The numbering of the partials and harmonics is then usually the same; the second partial is the second harmonic, etc. But if there are inharmonic partials, the numbering no longer coincides. Overtones are numbered as they appear above the fundamental. So strictly speaking, the first overtone is the second partial (and usually the second harmonic). As this can result in confusion, only harmonics are usually referred to by their numbers, and overtones and partials are described by their relationships to those harmonics.

Mechanical systems

[edit]Consider a spring, fixed at one end and having a mass attached to the other; this would be a single degree of freedom (SDoF) oscillator. Once set into motion, it will oscillate at its natural frequency. For a single degree of freedom oscillator, a system in which the motion can be described by a single coordinate, the natural frequency depends on two system properties: mass and stiffness; (providing the system is undamped). The natural frequency, or fundamental frequency, ω0, can be found using the following equation:

where:

- k = stiffness of the spring

- m = mass

- ω0 = natural frequency in radians per second.

To determine the natural frequency in Hz, the omega value is divided by 2π. Or:

where:

- f0 = natural frequency (SI unit: hertz)

- k = stiffness of the spring (SI unit: newtons/metre or N/m)

- m = mass (SI unit: kg).

While doing a modal analysis, the frequency of the 1st mode is the fundamental frequency.

This is also expressed as:

where:

- f0 = natural frequency (SI unit: hertz)

- l = length of the string (SI unit: metre)

- μ = mass per unit length of the string (SI unit: kg/m)

- T = tension on the string (SI unit: newton)[11]

See also

[edit]- Greatest common divisor

- Hertz

- Missing fundamental

- Natural frequency

- Oscillation

- Harmonic series (music)#Terminology

- Pitch detection algorithm

- Scale of harmonics

References

[edit]- ^ "sidfn". Phon.UCL.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ Lemmetty, Sami (1999). "Phonetics and Theory of Speech Production". Acoustics.hut.fi. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ "Fundamental Frequency of Continuous Signals" (PDF). Fourier.eng.hmc.edu. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-14. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ "Standing Wave in a Tube II – Finding the Fundamental Frequency" (PDF). Nchsdduncanapphysics.wikispaces.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ "Physics: Standing Waves". Physics.Kennesaw.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ Pollock, Steven (2005). "Phys 1240: Sound and Music" (PDF). Colorado.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-15. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ "Standing Waves on a String". Hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ "Creating musical sounds". OpenLearn. Open University. Archived from the original on 2020-04-09. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ Benward, Bruce and Saker, Marilyn (1997/2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, 7th ed.; p. xiii. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ Pierce, John R. (2001). "Consonance and Scales". In Cook, Perry R. (ed.). Music, Cognition, and Computerized Sound. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-53190-0.

- ^ "About the String Calculator". www.wirestrungharp.com.