Multithreading (computer architecture)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

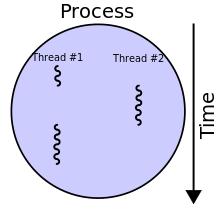

In computer architecture, multithreading is the ability of a central processing unit (CPU) (or a single core in a multi-core processor) to provide multiple threads of execution. There are two common approaches for multi threading: parallel multithreading and concurrent multithreading.[1]

Overview[edit]

The multithreading paradigm has become more popular as efforts to further exploit instruction-level parallelism have stalled since the late 1990s. This allowed the concept of throughput computing to re-emerge from the more specialized field of transaction processing. Even though it is very difficult to further speed up a single thread or single program, most computer systems are actually multitasking among multiple threads or programs. Thus, techniques that improve the throughput of all tasks result in overall performance gains.

Two major techniques for throughput computing are multithreading and multiprocessing.

Advantages[edit]

If a thread gets a lot of cache misses, the other threads can continue taking advantage of the unused computing resources, which may lead to faster overall execution, as these resources would have been idle if only a single thread were executed. Also, if a thread cannot use all the computing resources of the CPU (because instructions depend on each other's result), running another thread may prevent those resources from becoming idle.

Disadvantages[edit]

Multiple threads can interfere with each other when sharing hardware resources such as caches or translation lookaside buffers (TLBs). As a result, execution times of a single thread are not improved and can be degraded, even when only one thread is executing, due to lower frequencies or additional pipeline stages that are necessary to accommodate thread-switching hardware.

Overall efficiency varies; Intel claims up to 30% improvement with its Hyper-Threading Technology,[2] while a synthetic program just performing a loop of non-optimized dependent floating-point operations actually gains a 100% speed improvement when run in parallel. On the other hand, hand-tuned assembly language programs using MMX or AltiVec extensions and performing data prefetches (as a good video encoder might) do not suffer from cache misses or idle computing resources. Such programs therefore do not benefit from hardware multithreading and can indeed see degraded performance due to contention for shared resources.

From the software standpoint, hardware support for multithreading is more visible to software, requiring more changes to both application programs and operating systems than multiprocessing. Hardware techniques used to support multithreading often parallel the software techniques used for computer multitasking. Thread scheduling is also a major problem in multithreading.

Types of multithreading[edit]

Interleaved/Temporal multithreading[edit]

Coarse-grained multithreading[edit]

The simplest type of multithreading occurs when one thread runs until it is blocked by an event that normally would create a long-latency stall. Such a stall might be a cache miss that has to access off-chip memory, which might take hundreds of CPU cycles for the data to return. Instead of waiting for the stall to resolve, a threaded processor would switch execution to another thread that was ready to run. Only when the data for the previous thread had arrived, would the previous thread be placed back on the list of ready-to-run threads.

For example:

- Cycle i: instruction j from thread A is issued.

- Cycle i + 1: instruction j + 1 from thread A is issued.

- Cycle i + 2: instruction j + 2 from thread A is issued, which is a load instruction that misses in all caches.

- Cycle i + 3: thread scheduler invoked, switches to thread B.

- Cycle i + 4: instruction k from thread B is issued.

- Cycle i + 5: instruction k + 1 from thread B is issued.

Conceptually, it is similar to cooperative multi-tasking used in real-time operating systems, in which tasks voluntarily give up execution time when they need to wait upon some type of the event. This type of multithreading is known as block, cooperative or coarse-grained multithreading.

The goal of multithreading hardware support is to allow quick switching between a blocked thread and another thread ready to run. Switching from one thread to another means the hardware switches from using one register set to another. To achieve this goal, the hardware for the program visible registers, as well as some processor control registers (such as the program counter), is replicated. For example, to quickly switch between two threads, the processor is built with two sets of registers.

Additional hardware support for multithreading allows thread switching to be done in one CPU cycle, bringing performance improvements. Also, additional hardware allows each thread to behave as if it were executing alone and not sharing any hardware resources with other threads, minimizing the amount of software changes needed within the application and the operating system to support multithreading.

Many families of microcontrollers and embedded processors have multiple register banks to allow quick context switching for interrupts. Such schemes can be considered a type of block multithreading among the user program thread and the interrupt threads.[citation needed]

Fine grained multithreading[edit]

The purpose of Fine grained multithreading is to remove all data dependency stalls from the execution pipeline. Since one thread is relatively independent from other threads, there is less chance of one instruction in one pipelining stage needing an output from an older instruction in the pipeline. Conceptually, it is similar to preemptive multitasking used in operating systems; an analogy would be that the time slice given to each active thread is one CPU cycle.

For example:

- Cycle i + 1: an instruction from thread B is issued.

- Cycle i + 2: an instruction from thread C is issued.

This type of multithreading was first called barrel processing, in which the staves of a barrel represent the pipeline stages and their executing threads. Interleaved, preemptive, fine-grained or time-sliced multithreading are more modern terminology.

In addition to the hardware costs discussed in the block type of multithreading, interleaved multithreading has an additional cost of each pipeline stage tracking the thread ID of the instruction it is processing. Also, since there are more threads being executed concurrently in the pipeline, shared resources such as caches and TLBs need to be larger to avoid thrashing between the different threads.

Simultaneous multithreading[edit]

The most advanced type of multithreading applies to superscalar processors. Whereas a normal superscalar processor issues multiple instructions from a single thread every CPU cycle, in simultaneous multithreading (SMT) a superscalar processor can issue instructions from multiple threads every CPU cycle. Recognizing that any single thread has a limited amount of instruction-level parallelism, this type of multithreading tries to exploit parallelism available across multiple threads to decrease the waste associated with unused issue slots.

For example:

- Cycle i: instructions j and j + 1 from thread A and instruction k from thread B are simultaneously issued.

- Cycle i + 1: instruction j + 2 from thread A, instruction k + 1 from thread B, and instruction m from thread C are all simultaneously issued.

- Cycle i + 2: instruction j + 3 from thread A and instructions m + 1 and m + 2 from thread C are all simultaneously issued.

To distinguish the other types of multithreading from SMT, the term "temporal multithreading" is used to denote when instructions from only one thread can be issued at a time.

In addition to the hardware costs discussed for interleaved multithreading, SMT has the additional cost of each pipeline stage tracking the thread ID of each instruction being processed. Again, shared resources such as caches and TLBs have to be sized for the large number of active threads being processed.

Implementations include DEC (later Compaq) EV8 (not completed), Intel Hyper-Threading Technology, IBM POWER5/POWER6/POWER7/POWER8/POWER9, IBM z13/z14/z15, Sun Microsystems UltraSPARC T2, Cray XMT, and AMD Bulldozer and Zen microarchitectures.

Implementation specifics[edit]

A major area of research is the thread scheduler that must quickly choose from among the list of ready-to-run threads to execute next, as well as maintain the ready-to-run and stalled thread lists. An important subtopic is the different thread priority schemes that can be used by the scheduler. The thread scheduler might be implemented totally in software, totally in hardware, or as a hardware/software combination.

Another area of research is what type of events should cause a thread switch: cache misses, inter-thread communication, DMA completion, etc.

If the multithreading scheme replicates all of the software-visible state, including privileged control registers and TLBs, then it enables virtual machines to be created for each thread. This allows each thread to run its own operating system on the same processor. On the other hand, if only user-mode state is saved, then less hardware is required, which would allow more threads to be active at one time for the same die area or cost.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ The Art of Concurrency A Thread Monkey's Guide to Writing Parallel Applications. O'Reilly Media. 2009. ISBN 9780596555788.

- ^ "Intel Hyper-Threading Technology, Technical User's Guide" (PDF). p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-21.

External links[edit]

- A Survey of Processors with Explicit Multithreading, ACM, March 2003, by Theo Ungerer, Borut Robi and Jurij Silc

- Operating System | Difference between Multitasking, Multithreading and Multiprocessing GeeksforGeeks, 6 Sept. 2018.