Turda

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2007) |

Turda | |

|---|---|

Republic Square Greek Catholic Church Turda City Hall, with statue of Ioan Rațiu Central area of Turda | |

Location in Cluj County | |

| Coordinates: 46°34′N 23°47′E / 46.567°N 23.783°E | |

| Country | Romania |

| County | Cluj |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2024) | Cristian-Octavian Matei[1] (PNL) |

| Area | 91.43 km2 (35.30 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 315 m (1,033 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 436 m (1,430 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 310 m (1,020 ft) |

| Population (2021-12-01)[2] | 43,319 |

| • Density | 470/km2 (1,200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EET/EEST (UTC+2/+3) |

| Postal code | 401001–401189 |

| Area code | +40 x64 |

| Vehicle reg. | CJ |

| Website | primariaturda |

Turda (Romanian pronunciation: [ˈturda]; Hungarian: Torda, Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈtorda]; German: Thorenburg; Latin: Potaissa) is a city in Cluj County, Transylvania, Romania. It is located in the southeastern part of the county, 34.2 km (21.3 mi) from the county seat, Cluj-Napoca, to which it is connected by the European route E81, and 6.7 km (4.2 mi) from nearby Câmpia Turzii.

The city consists of four neighborhoods: Turda Veche, Turda Nouă, Oprișani and Poiana. It is traversed from west to east by the Arieș River and north to south by its tributary, Valea Racilor.

History

[edit]Ancient times

[edit]

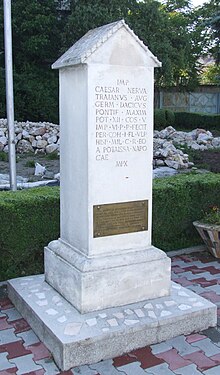

There is evidence of human settlement in the area dating to the Middle Paleolithic, some 60,000 years ago.[3] The Dacians established a town that Ptolemy in his Geography calls Patreuissa, which is probably a corruption of Patavissa or Potaissa, the latter being more common. It was conquered by the Romans, who kept the name Potaissa, between AD 101 and 106, during the rule of Trajan, together with parts of Decebal's Dacia.[4]

The name Potaissa is first recorded on a Roman milliarium discovered in 1758 in the nearby Aiton commune.[5]

The legionary fortress established as the basecamp of the Legio V Macedonica from 166 to 274 was named Potaissa too. The city became a municipium, then a colonia.

The Potaissa salt mines were worked in the area since prehistoric times.

From the reign of Gordian III (238–244) numerous treasures were excavated from Turda, Țaga, Viișoara, and Mărtinești, showing that in this time the defense was breaking under the Carps, Goths, Gepids, and Vandals.[6]

Objects dated to post-Aurelian retreat found at the site (for example an inscribed onyx gem depicting the Good Shepherd, and silver coins of Diocletian) together with a large burial containing sarcophagi and a cremation stone box point at continuous habitation until the early fifth century.[7] The situation changes in the next two centuries when dwellings and cemeteries superpose the Roman site, in a similar manner to Apulum and Sirmium.[8] After conquering the place, the Huns settled down near.[9] From this time three solidus were found from graves. Burying with coins was a Gepid tradition not typical of the Huns, meaning that they settled their vassals in Transylvania too.[6]

Middle Ages

[edit]The territory changed hands between the Gepids and Langobards multiple times before both were expelled by the Avars.[9]

After the Hungarian conquest, the kindred Kalocsa settled here. Their center was called Tordavár ("castle of Torda"), and another important estate was Tordalaka ("home of Torda") as of 1075.[6][9] The name probably derives from Old Bulgarian *tvьrdъ meaning citadel, fortress.[10]

Saxons settled in the area in the 12th century. Much of the town was destroyed during the Tatar invasion in 1241–1242, however most of its inhabitants survived by hiding in the cave system. King Stephen V ensured its quick revival by giving privileges.[9]

On 8 January, 1288, Ladislaus IV attended the first national assembly in Torda and recruited an army of Transylvanians to repel the Cuman invasion. He pursued the Cumans back to the border. During this time the Hungarians were the absolute majority in the city. Numerous meetings were held here afterwards.[9]

The Hungarian Diet was held here in 1467, by Matthias Corvinus. Later, in the 16th century, Turda was often the residence of the Transylvanian Diet, too. After the Battle of Mohács, the city became part of the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom and since 1570 the Principality of Transylvania. The 1558 Diet of Turda declared free practice of both the Catholic and Lutheran religions. In 1563 the Diet also accepted the Calvinist religion, and in 1568 it extended freedom to all religions, declaring that "It is not allowed to anybody to intimidate anybody with captivity or expelling for his religion" – a freedom unusual in medieval Europe. This Edict of Turda is the first attempt at legislating general religious freedom in Christian Europe (though its legal effectiveness was limited).

In 1609 Gabriel Báthori granted new privileges to Turda. These were confirmed later by Gabriel Bethlen. In the battle of Turda, Ahmed Pasha defeated George II Rákóczi in 1659.

Modern times

[edit]In 1711 the Grand Principality of Translyvania was formed which became in 1804 part of the Austrian Empire. In 1867, by the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, the city became again part of Hungary. After the First World War following the proclamation of the Union of Transylvania with Romania, Turda as well became part of Romania by the Treaty of Trianon.[11] In 1944, the Battle of Turda took place here, between German and Hungarian forces on one side and Soviet and Romanian forces on the other. It was the largest battle fought in Transylvania during World War II.

From the late 1950s, Turda became a rather important industrial centre, housing factories for chemical, electrotechnical ceramics, cement, glass and steel cables. The nearby Câmpia Turzii town hosted a siderurgy (steel) plant. The city centre of Turda saw redevelopment in the late 1980s, including a House of Culture that hasn't been finished up to this date. Many houses in the historic center were demolished to create space for apartment buildings. The town's role of an industrial powerhouse has diminished from the 1990s onwards, but tourist attractions have kept the city in a good state up to today.[citation needed]

Climate

[edit]Turda has a continental climate, characterised by warm dry summers and cold winters. The climate is influenced by the city's proximity to the Apuseni Mountains, as well as by urbanisation. Some West-Atlantic influences are present during winter and autumn. Winter temperatures are often below 0 °C (32 °F), even though they rarely drop below −10 °C (14 °F). On average, snow covers the ground for 65 days each winter. In July and August, the average temperature is approximately 18 °C (64 °F), despite the fact that temperatures sometimes reach 35–40 °C (95–104 °F) in mid-summer in the city centre. Although average precipitation and humidity during summer is low, there are infrequent yet heavy and often violent storms. During spring and autumn, temperatures vary between 13–18 °C (55–64 °F), and precipitation during this time tends to be higher than in summer, with more frequent yet milder periods of rain.[citation needed]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1912 | 13,455 | — |

| 1930 | 20,023 | +48.8% |

| 1948 | 25,905 | +29.4% |

| 1956 | 33,614 | +29.8% |

| 1966 | 42,307 | +25.9% |

| 1977 | 55,294 | +30.7% |

| 1992 | 61,200 | +10.7% |

| 2002 | 55,770 | −8.9% |

| 2011 | 47,744 | −14.4% |

| 2021 | 43,319 | −9.3% |

| Source: Census data | ||

According to the Hungarian census from year 1910, from 13,455 inhabitants, 9,674 were Hungarians, 3,389 Romanians, and 100 Germans.[12]

According to the 2011 Romanian census, there were 47,744 people living within the city. Of this population, 84.7% were ethnic Romanians, while 8.98% were ethnic Hungarians, 6.03% ethnic Roma, and 0.4% others.[13]

At the 2021 census, Turda had a population of 43,319, a decrease of 9.3% from the previous census.[14]

Notable people

[edit]- Eta Boeriu

- Miklós Bogáthi Fazekas

- Andreea Cacovean

- Horia Crișan

- Radu Crișan

- Emilian Dolha

- Veronica Drăgan

- Moise Dragoș

- Étienne Hajdú

- Miklós Jósika

- Baruch Kimmerling

- Ecaterina Orb-Lazăr

- Andrei Mureșan

- Ionuț Mureșan

- Camil Mureșanu

- Mona Muscă

- Cristina Pîrv

- Ion Rațiu

- Alin Rus

- Júlia Sigmond

- Ion Suru

- Rareș Takács

- Mădălina Tătar

- István Timár-Geng

- Moise Vass

- Cosmin Vâtcă

- Septimiu Sever

- Csaba Lászlóffy

- Aladár Lászlóffy

- János Thordai

- János Abacs

- Sámuel Köteles

- László Kőváry

- Miklós Szigethy Csehi

- Ottó Kőváry

- Károly Viski

- Béla Varga

- János Tulogdy

- István Barra

- Albert Nagy

- Ádám Anavi

- Dezső Baróti

- Erzsébet Keszy-Harmath

- Samu Tóth

- Elek Csetri

- László Darkó

- Etelka Szabó Adorján

- Zoltán Tibor Sinka

- Arnold Gross

- Sándor Szenyei

- Gábor Tőrös

- Zoltán Tatár

- Mária Újvári

- Jenő Attila Kessler

- Katalin Simonffy

- István Bajusz

Tourism

[edit]See also

[edit]- Decree of Turda

- Universitas Valachorum

- List of Transylvanian Saxon localities

- Ancient history of Transylvania, History of Transylvania

- Franziska Tesaurus

- Edict of Torda

International relations

[edit]Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Turda is twinned with:

Picture gallery

[edit]-

City Hall

-

Mendel Villa

-

Palace of Finance

-

Princely Palace, now the History Museum

-

Orthodox Cathedral

References

[edit]- ^ "Results of the 2020 local elections". Central Electoral Bureau. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Populaţia rezidentă după grupa de vârstă, pe județe și municipii, orașe, comune, la 1 decembrie 2021" (XLS). National Institute of Statistics.

- ^ (in Romanian) "Comuna primitivă" at the Turda City Hall site; accessed March 21, 2013

- ^ (in Romanian) "Epoca dacică" at the Turda City Hall site; accessed March 21, 2013

- ^ Lazarovici et al. 1997, pp. 202–3 (6.2 Cluj in the Old and Ancient Epochs)

- ^ a b c Bicsok, Zoltán (2001). Torda város története és statútuma [History and statute of the city of Torda] (PDF). Vol. Erdélyi Turdományos Füzetek 229. Erdélyi Múzem-Egyesület. ISBN 973-99299-9-0.

- ^ Wanner, Rob; De Sena, Eric (2016). "Reflections on the Immediate Post-Roman Phase of Three Dacian Cities: Napoca, Potaissa and Porolissum". academia.edu. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- ^ Nemeti, Sorin; Barbocz, Beata (2023). "The 5th–6 th Century AD Settlement from the Fortress of legio V Macedonica at Potaissa". Academia.edu. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Visszapillantás Torda múltjába" [Flashback in the past of Torda]. Torda (in Hungarian).

- ^ Nicolae Drăganu: Toponimie și istorie, 1928, page 149

- ^ (in Romanian) "Turda în perioada interbelică" at the Turda City Hall site; accessed June 3, 2013

- ^ "1910. Évi Népszámlálás 1. A népesség főbb adatai községek és népesebb puszták, telepek szerint (1912) | Könyvtár | Hungaricana".

- ^ "Structura Etno-demografică a României". www.edrc.ro. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ "Populația rezidentă după grupa de vârstă, pe județe și municipii, orașe, comune, la 1 decembrie 2021" (in Romanian). INSSE. May 31, 2023.

- ^ "National Commission for Decentralised cooperation". Délégation pour l’Action Extérieure des Collectivités Territoriales (Ministère des Affaires étrangères) (in French). Archived from the original on August 5, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- "INP - Museums and Collections in Romania". Cimec.ro. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- "Turda - Romania". Britannica.com. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

External links

[edit]- (in Romanian) Official site of the city hall

- TurdaTurism.ro

- Fundatia Potaissa