Fouta Djallon

Fouta Djallon (Fula: Fuuta Jaloo, ࢻُوتَ جَلࣾو, 𞤊𞤵𞥅𞤼𞤢 𞤔𞤢𞤤𞤮𞥅; Arabic: فوتا جالون) is a highland region in the center of Guinea, roughly corresponding with Middle Guinea, in West Africa.

Etymology

[edit]The Fulani people call the region Fuuta-Jaloo ( ࢻُوتَ جَلࣾو) in the Pular language.[a] The origin of the first word in the name is from the Fula word for any region inhabited by the Fulɓe and the second from the Jallonke people, who inhabited the region before the Fula arrived.[1][2]

History

[edit]Since the 17th century, the Fouta Djallon region has been a stronghold of Islam. Early revolutionaries led by Karamokho Alfa and Ibrahim Sori set up a federation divided into nine provinces. Several succession crises weakened the central power located in Timbo until 1896, when the last Almamy, Bubakar Biro, was defeated by the French army in the Battle of Porédaka.[3]

The Fulɓe of Fouta Djallonke spearheaded the expansion of Islam in the region.[4] Fulɓe Muslim scholars developed indigenous literature using the Arabic alphabet.[5] Known as Ajamiyya, this literary achievement is represented by such great poet-theologians as Tierno Muhammadu Samba Mombeya, Tierno Saadu Dalen, Tierno Aliou Boubha Ndyan, Tierno Jaawo Pellel etc.[6] In its heyday, it was said that Fuuta-Jaloo was a magnet of learning, attracting students from Kankan to the Gambia, and featuring Jakhanke clerics at Tuba as well as Fulɓe teachers. It acted as the nerve centre for trading caravans heading in every direction. The more enterprising commercial lineages, of whatever ethnic origin, established colonies in the Futanke hills and along the principal routes. It served their interests to send their sons to Futanke schools, to support the graduates who came out to teach, and in general to extend the vast pattern of influence that radiated from Futa Jalon.[6]

Amadou Hampâté Bâ has called Fuuta-Jaloo "the Tibet of West Africa" in homage to the spiritual and mystic (Sufi) tradition of its clerics.

Geography

[edit]Fouta-Djallon consists mainly of rolling grasslands, at an average elevation of about 900 m (3,000 ft). The highest point, Mount Loura, rises to 1,515 m (4,970 ft). The plateau consists of thick sandstone formations that overlie granitic basement rock. Erosion by rain and rivers has carved deep jungle canyons and valleys into the sandstone.

It receives a great deal of rainfall, and is the headwaters of four major rivers and other medium ones:

- Tinkisso River (major upriver tributary of the Niger)

- Gambia River

- Senegal River

- Pongo River

- Nunez River

- Konkouré River

- Rio Cogon

- Rio Kapatchez

- Mellacorée River

It is, thus, sometimes called the watertower (chateau d'eau in French literature) of West Africa. Some authors also refer to Fouta Jallon as the "Switzerland of West Africa." This is a common expression whose origin may be unknown.[7]

Population

[edit]

The population consists predominantly of Fulɓe [sing. Pullo], also known as Fula or Fulani. In Fouta Djallon, their language is called Pular or Pulaar. The broader language area bears the name Fula/Fulfulde, and it is spoken in numerous countries in West and Central Africa. The Fulani (French: Peul) population represents between 32.1% and 40% of the population in Guinea.[8]

Economy

[edit]The largest town in the region is Labé. Mainly rural the economy covers animal husbandry (cattle, sheep, goats), agriculture, gathering, trading, and marginal tourism.

The Fulbe practice a form of natural farming that can be recognized today as biointensive agriculture. The region's main cash crops are bananas and other fruits. The main field crop is fonio, although rice is grown in richer soils. Most soils degrade quickly and are highly acidic with aluminum toxicity, which limits the range of crops that can be grown without significant soil management.

Biointensive agriculture

[edit]

Sometime in the late 18th century, the Fulɓe in Fouta Djallonke developed a type of biointensive agriculture, probably out of necessity, since the conquered indigenous women were taken into the households of their Islamic overlords whose livestock became their responsibility. Combining animal husbandry and sedentary agriculture into an efficient system of agropastoralism required a new way of organizing daily life. Livestock, which included horses and cattle, ate more and produced more waste than what the indigenous farmers were accustomed. Since the livestock had to be protected from wildlife at night, they were brought into the family compound, referred to by the French as a tapade, and locally as cuntuuje (sing. suntuure) in the Pular language.[4]

Today, livestock graze in open areas during the day but are sheltered in corrals during the night, except for goats, which are permitted to manage on their own within limits. A similar pattern must have developed by the latter part of the 18th into the 19th century. Nonetheless, the disposal of livestock waste, which became woman's work, required a systematic way of disposing of it. And, over time, the women worked out a method for doing so. In organic gardening, their solution is called sheet composting or mulching. Over time, the women mixed a variety of other organic matter with the manure (kitchen scraps, harvest residues, and vegetative materials from a living fence or hedgerow) and piled it each day on their garden beds and trees to decompose and become nutritious humus. In the 20th century, livestock among the Fulɓe shifted from large animals to smaller types. Horses, perhaps due to the tsetse fly, decreased, while goats, sheep, pigs, and poultry increased, and n'dama cattle remain an integral asset.

The tapade gardens of Fouta Djallon have been highly researched by international scholars from various disciplines. This research has revealed that the cuntuuje system has a higher soil nutrient level than any other soil in the region. Almost all labor, except for the initial preparation, is performed and managed by women and children, in the past and now, within each family group. The gardens are important for both food and cash crops for their families. PLEC, a project of the United Nations University, measured yields on 6.5 ha from tapade fields at Misiide Heyre, Fouta Djallon and found that maize yielded up to 7 t/ha, cassava 21 t/ha, sweet potatoes 19 t/ha, and groundnuts (peanuts) about 8 t/ha.[9]

Each suntuure is about 1-hectare (2.5 acres) on average, so referring to them as gardens is not accurate, neither for their size nor complexity. The cuntuuje represents a systems approach to food production, and is distinguished by their agrodiversity, as well as the way the people intensively use and maximize a limited amount of land. Today, the cuntuuje gardens continue to produce a significant quantity and variety of agricultural products.[10]

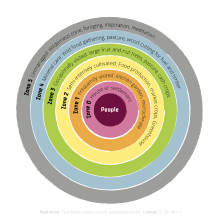

The living fences that surround each suntuure are not just a barrier to keep out people, wild animals, and domestic livestock. In the permaculture vocabulary, the fence is a vegetative berm, and is instrumental in the process of nutrient cycling and nutrient retention within the suntuure. In other words, the cuntuuje represent a sustainable biointensive polyculture farm system and landscape architecture, housing one or more microclimate ecosystems and are examples of what we know today to be a permaculture design. The graphic in this section is a mind map of the internal zones and sectors found typically in a suntuure environment.

The interior of the suntuure, Zones 1-3 (internal gate, entryway, privacy screen, and residence) are reserved primarily for family members. It is in Zones 4 and 5 (the hoggo[check spelling] and suntuure living fence) where most activities of daily life occur. Here, visitors are greeted at a secondary shelter or pavilion, work on gardens (hoggos) is organized, children spend the day in play and work if of age, and afternoon prayers, naps, conversations, and meals occur until dark. Zone 6 is the outside world.

In 2003, the cuntuuje of Fuuta-Jalon were recognized by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UNFAO) as one of the Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems.[11]

Migration

[edit]Fuuta-Jalon has historically had a high degree of migration, usually short-term, and mainly to Senegal and Sierra Leone. Many Fulbe fled to Senegal after Sekou Toure became president of independent Guinea in 1959. Many settled in Leidi Ulu west of the Gambia River and began farming in addition to keeping cattle. They remembered Guinea as a land of fruit and honey where laborious agriculture was not necessary.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The name in Pular, and in the Fula (macro)language of which it is a part, is also sometimes spelled Fuuta-Jalon. French is the official language of Guinea, and Fouta-Djallon or sometimes Foûta Djallon is the French spelling. Common English spellings include Futa Jallon and Futa Jalon.

References

[edit]- ^ Mohamed Saidou N'Daou (2005). Sangalan Oral Traditions: History, Memories, and Social Differentiation. Carolina Academic Press. pp. 7, 31. ISBN 978-1-59-460104-0.

- ^ C. Magbaily Fyle (1979). The Solima Yalunka Kingdom: Pre-colonial Politics, Economics & Society. Nyakon Publishers. p. 6.

- ^ Mamdani, Mahmood. "Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: America, the Cold War, and the Roots of Terror." Pantheon, 2004.

- ^ a b Mats Widgren, "Slaves: Inequality and sustainable agriculture in pre-colonial West Africa." In, Ecology and Power: Struggles over land and material resources in the past, present, and future. London: Routledge, 2012. pp. 97-107.

- ^ Les Peuls − Land of Faith and Liberty. (video)

- ^ a b David Robinson. The Holy War of Umar Tal: the Western Sudan in the mid-nineteenth century. Clarendon Press. Oxford University Press, 1985.

- ^ Africa Travel Magazine

- ^ Cia.gov. Retrieved 2015-08-15

- ^ Boiro, Ibrahima; Barry, A. Karim; & and Diallo, Amadou. (2003). "Guinée." Chap. 5. In Harold Brookfield, Helen Parsons & Muriel Brookfield (eds.). Agrodiversity: Learning from farmers across the world., pp. 110-133. Tokyo: United Nations University Press. Specific information cited from p. 116.

- ^ Harold Brookfield, Exploring Agrodiversity, Chapter 5. New York: Columbia UP, 2001. pp. 80-99; Véronique André-Lamat, Gilles Pestaña, and Georges Rossi. "Foreign Representations and Local Realities: Agropastoralism and Environmental Issues in the Fouta Djalon Tablelands, Republic of Guinea." Mountain Research and Development, Vol. 23, No 2, May 2003:149-155; Carole LAUGA-SALLENAVE, "Le clos et l'ouvert Terre et territoire au Fouta-Djalon." In, Bonnemaison Joël (ed.), Cambrézy Luc (ed.), Quinty Bourgeois Laurence (ed.). Le territoire, lien ou frontière? : identités, conflits ethniques, enjeux et recompositions territoriales. Paris: ORSTOM, 1997, 10 p. (Colloques et Séminaires); Carole LAUGA-SALLENAVE, Terre et territoire au Fouta-Djalon (Guinée), GRET - University Paris X, 1999.

- ^ Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS); "Tapade Cultivation System, Guinea," Archived 2014-08-19 at the Wayback Machine A project of the United Nations Food & Agriculture Organization.

Sources

[edit]- A. Demougeot Notes sur l'organisation politique et administrative du Labé avant et après l'occupation française

- Boubacar Barry Bokar Biro, le dernier grand almamy du Fouta-Djallon

- Christopher Harrison French Islamic policy in the Fuuta-Jalon 1909-1912

- D. P. Cantrelle, M. Dupire L'endogamie des Peuls du Fouta-Djallon

- David Robinson (1985) The Holy War of Umar Tal: the Western Sudan in the mid-nineteenth century

- Gustav Deveneaux. Buxtonianism and Sierra Leone: The 1841 Timbo Expedition

- Hanson, John H. (1996) Migration, Jihad and Muslim Authority in West Africa: the Futanke colonies in Karta Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, ISBN 0-253-33088-2

- J. Suret-Canale The Fouta-Djallon chieftaincy

- J. Suret-Canale La fin de la chefferie en Guinée

- J. Suret-Canale Essai sur la signification sociale et historique des hégémonies peules (XVII-XIXèmes siècles)

- Joseph Earl Harris (1965) The Kingdom of Fouta-Diallon

- Kevin Shillington Fuuta-Jalon: Nineteenth Century

- Louis Tauxier Moeurs et Histoire des Peuls, Livre III. Les Peuls du Fouta-Djallon

- Marguerite Verdat. Le Ouali de Gomba. Essai Historique

- Paul Marty L'Islam en Guinée. Fouta-Diallon

- Shaikou Baldé L'élevage au Fouta-Djallon (régions de Timbo et de Labé

- Terry Alford Abdul-Rahman. Prince Among Slaves

- Thierno Diallo (1972) Les institutions politiques du Fouta-Djallon au XIXè siècle

- Thierno Diallo Alfa Yaya : roi du Labé (Fouta Djalon)

Further reading

[edit]- De Sanderval, La conquête du Fouta-Djallon (Paris, 1899)

- Dölter, Ueber die Capverden nach dem Rio Grande und Futa Dschallon (Leipzig, 1884)

- Marchat, Les rivières du sud et le Fouta-Djallon (Paris, 1906)

- Noirot, A travers le Fouta-Djallon et le Bamboue (Paris, 1885)