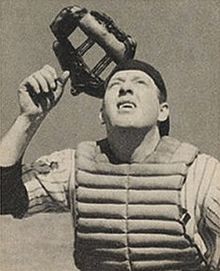

Buddy Rosar

| Buddy Rosar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Catcher | |

| Born: July 3, 1914 Buffalo, New York, U.S. | |

| Died: March 13, 1994 (aged 79) Rochester, New York, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| April 29, 1939, for the New York Yankees | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 19, 1951, for the Boston Red Sox | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .261 |

| Home runs | 18 |

| Runs batted in | 367 |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

Warren Vincent "Buddy" Rosar (July 3, 1914 – March 13, 1994) was an American professional baseball player. He played in Major League Baseball as a catcher from 1939 to 1951 for the New York Yankees, Cleveland Indians, Philadelphia Athletics, and Boston Red Sox. A five-time All-Star, Rosar was regarded as an excellent defensive catcher, setting a major league record for consecutive games without an error by a catcher.[1] He is one of only three catchers in Major League history to catch at least 100 games in a single season without committing an error.[2]

Baseball career

[edit]Rosar was first discovered in 1934 when he was chosen to play in an All-Star game for amateur baseball players from Buffalo, New York.[3] The wife of New York Yankees manager, Joe McCarthy, attended the game and was so impressed with Rosar's catching ability that she told her husband about him.[3] McCarthy sent Yankees' scout, Gene McCann to look at Rosar before the team signed him as an amateur free agent.[3] He played for the 1937 Newark Bears team that won the International League pennant by 25+1⁄2 games to become known as one of the best minor league teams of all time.[3][4] Rosar hit .387 with the Bears in 1938 to win the International League batting championship.[5]

Rosar made his major league debut with the Yankees on April 29, 1939 at the age of 24.[6] From 1939 to 1942, he served as the Yankees' back up catcher to the future Hall of Fame inductee Bill Dickey.[7] By the middle of the 1940 season, Rosar was out-hitting Dickey with a .343 batting average compared to Dickey's .226 average, although he appeared in only half as many games as the Yankees were reluctant to relegate Dickey to second-string status.[8][9][10] On July 19, 1940, he hit for the cycle in a game against the Cleveland Indians.[11] Rosar appeared in 73 games in 1940 and set career-highs with a .298 batting average and a .357 on-base percentage.[6] In 1941, he hit well above .300 until the final month of the season before tapering off to end the year with a .287 average in 67 games as, the Yankees won the American League pennant by 17 games over the Boston Red Sox.[12] Rosar made only one appearance in the 1941 World Series as a late-inning defensive replacement for Dickey in Game 2 as, the Yankees went on to defeat the Brooklyn Dodgers in five games.[13][14] Despite being a second string catcher, American League managers chose Rosar to be a reserve player in the 1942 All-Star Game over all other starting catchers in the league, with the exception of Birdie Tebbetts of the Detroit Tigers, who was selected to start the game.[15]

With the outbreak of World War II creating doubts as to whether Major League Baseball would continue to operate during wartime, Rosar asked Yankees manager, Joe McCarthy, for permission to travel to Buffalo in July 1942 to take examinations to join the Buffalo police force and, to be with his wife who was about to have a baby.[16] McCarthy refused to allow him to leave because Dickey was sidelined with an injury leaving only unseasoned rookie catcher Eddie Kearse available but, Rosar decided to leave without permission.[17] When he returned to the club three days later, he found that McCarthy had replaced him with Rollie Hemsley and sent Kearse to the minor leagues, relegating Rosar to third-string catcher.[16] Rosar had been seen as a successor to the aging Dickey but, after flouting the authority of the Yankees management, he would be traded to the Cleveland Indians by the end of the season.[18][19]

Although Indians manager, Lou Boudreau, named Gene Desautels as the Indians starting catcher at the beginning of the 1943 season, by the middle of the year Rosar was among the league leaders in hitting with a .313 average.[20][21] He was recognised by being named to his second All-Star team as a reserve in the 1943 All-Star Game.[22] He ended the season with a .283 batting average and 41 runs batted in.[6] He also led American League catchers in assists and in baserunners caught stealing.[23] In 1944, Rosar was assigned to a war job in Buffalo, New York before being transferred to another war job in Cleveland, leaving him available part-time to the Indians.[24] He was again hitting among the league leaders with a .324 average in June before fading to finish the year with a .263 batting average.[6][25][26] After two seasons with the Indians, Rosar refused to play at the beginning of the 1945 season because of a salary dispute.[27] The Indians responded by trading Rosar to the Philadelphia Athletics for catcher Frankie Hayes on May 29, 1945.[19]

Rosar had one of his best seasons in the major leagues with Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics in 1946, hitting for a .283 batting average and posted career-highs with 120 hits and 48 runs batted in.[6] He led American League catchers in assists, runners caught stealing, and fielding percentage, setting a record for errorless games by a catcher, posting a 1.000 fielding percentage in 117 games played as a catcher.[28][29] The next year he extended his perfect play to 147 games and was selected to be the starting catcher for the American League in the 1947 All-Star Game.[1][29][30] The errorless games record has since been broken by several players.

Rosar was hitting for just a .216 batting average by mid-season in 1948, but his defensive reputation won him the fans' vote as the American League's starting catcher in the 1948 All-Star Game.[31][32] During a three-season period between 1946 and 1948, Rosar committed only three errors.[6] By 1949, Mike Guerra had taken over as the Athletics' starting catcher, and Rosar would be traded to the Boston Red Sox in October 1949.[19] With the Red Sox, he was the third string catcher behind Birdie Tebbetts and Matt Batts in 1950 and then to Les Moss in 1951 before being released in October 1951.[6]

Career statistics

[edit]In a thirteen-year major league career, Rosar played in 988 games, with 836 hits for a .261 career batting average, along with 18 home runs and 367 runs batted in.[6] Despite his relatively low offensive statistics, Rosar's defensive skills earned him a place on the American League All-Star team five times during his career.[6] Rosar led all American League catchers in fielding percentage four years (1944, 1946–1948).[33] He also led the league three times in assists, twice in baserunners caught stealing and once in caught stealing percentage.[6] His 54.81% career caught stealing percentage ranks him third all-time behind only Roy Campanella and Gabby Hartnett.[34]

Rosar caught two no hitter games in his career, pitched by Dick Fowler in 1945, and Bill McCahan in 1947.[35] He has the best ratio of double plays to errors of any catcher in major league history.[36] Rosar holds the 20th Century career record for fewest passed balls per games caught (0.0300) with only 28 miscues in 934 games as catcher.[29] Rosar's .992 career fielding percentage was 10 points higher than the league average during his playing career, and at the time of his retirement in 1951, was the highest for a catcher in major league history.[37]

Later life

[edit]After Rosar's baseball career, he was employed as an engineer at a Ford plant near his hometown of Buffalo.[1] Rosar died on March 13, 1994, age 79, in Rochester, New York, while visiting the area.[38]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Buddy Rosar Obituary". The New York Times. March 16, 1994. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "Giants catcher Mike Matheny announces retirement". mlb.com. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Ronald, Mayer (1994), The 1937 Newark Bears: A Baseball Legend, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 978-0-8135-2153-4

- ^ "Hollywood In On Coming World Series". The Calgary Herald. Associated Press. September 26, 1941. p. 9. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ "1938 International League batting leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Buddy Rosar". Baseball Reference. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ William, McNeil (2006), Backstop: a history of the catcher and a sabermetric ranking of 50 all-time greats, McFarland Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7864-2177-0

- ^ "1940 Buddy Rosar Batting Log". Baseball Reference. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "1940 Bill Dickey Batting Log". Baseball Reference. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "Dickey Slipping But Yanks Find Buddy Rosar Capable Substitute". St. Petersburg Times. United Press. July 27, 1940. p. 9. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "July 19, 1940 Indians Yankees box score". Baseball Reference. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "1941 Buddy Rosar batting log". Baseball Reference. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ "1941 World Series Game 2 box score". Baseball Reference. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ "1941 World Series". Baseball Reference. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ "Yankees To Dominate American Loop All-Stars Again". Herald-Journal. Associated Press. June 26, 1942. p. 21. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ a b "Buddy Gets Protection". Time. August 3, 1942. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2007.

- ^ "Hemsley Picked For Job Buddy Rosar Gives Up". The Milwaukee Journal. United Press. July 20, 1942. p. 6. Retrieved November 9, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Discipline Scented In Deal That Involves Buddy Rosar". The Bend Bulletin. United Press. December 18, 1942. p. 2. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Buddy Rosar Trades and Transactions". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "Gene Desautels Gets First Call". Ottawa Citizen. Associated Press. April 3, 1943. p. 11. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ "Indians Drop In Standings But Not Their Hitters". Painesville Telegraph. June 15, 1943. p. 7. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ "Six Yankees And Six Indians Make All-Star Squad". The Miami News. Associated Press. July 1, 1943. p. 2. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ "1943 American League Fielding Leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ "Rosar, Tribe Catcher, Can Play Home Games". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. May 1, 1944. p. 3. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ "1944 Buddy Rosar batting log". Baseball Reference. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ "Musial Gains; Walker Slips". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. June 27, 1944. p. 4. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ "A's Send Hayes To Cleveland". St. Petersburg Times. United Press. May 30, 1945. p. 2. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "1946 American League Fielding Leaders". Baseball Reference. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Buddy Rosar". The Encyclopedia of Catchers. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "1947 All-Star Game". Baseball Reference. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "1948 Buddy Rosar batting log". Baseball Reference. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "1948 All-Star Game". Baseball Reference. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ Fielding Leaders. July 2001. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)[permanent dead link] - ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Caught Stealing Percentages". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ^ "Catchers Who Caught No Hitters". The Encyclopedia of Baseball Catchers. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ James, Bill (2003). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2722-0.

- ^ "Catchers career fielding percentages". The Encyclopedia of Baseball Catchers. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ "Ex-big leaguer Buddy Rosar dies". The Journal News. White Plains, New York. March 16, 1994. Retrieved November 16, 2017 – via newspaper.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Skelton, David E. "Buddy Rosar". SABR.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- 1914 births

- 1994 deaths

- American League All-Stars

- American people of French-Canadian descent

- Baseball players from Buffalo, New York

- Binghamton Triplets players

- Boston Red Sox players

- Cleveland Indians players

- Major League Baseball catchers

- Newark Bears (International League) players

- New York Yankees players

- Norfolk Tars players

- Philadelphia Athletics players

- Wheeling Stogies players