Ebola virus cases in the United States

| |

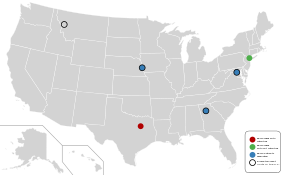

| Map of Ebola cases and infrastructure throughout the U.S. | |

|---|---|

| Cases contracted in the U.S. | 2 |

| Cases first diagnosed in U.S. | 4[note 1] |

| Cases evacuated to U.S. from other countries | 7[1] |

| Total cases | 11[note 2] |

| Deaths | 2[2] |

| Recoveries from Ebola | 9[note 2] |

| Active cases | 0 |

Four laboratory-confirmed cases of Ebola virus disease (commonly known as "Ebola") occurred in the United States in 2014.[3] Eleven cases were reported, including these four cases and seven cases medically evacuated from other countries.[4] The first was reported in September 2014.[5] Nine of the people contracted the disease outside the US and traveled into the country, either as regular airline passengers or as medical evacuees; of those nine, two died. Two people contracted Ebola in the United States. Both were nurses who treated an Ebola patient; both recovered.[4]

On September 30, 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that Thomas Eric Duncan, a 45-year-old Liberian national visiting the United States from Liberia, had been diagnosed with Ebola in Dallas, Texas.[6][7] Duncan, who had been visiting family in Dallas, was treated at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas.[8][9] By October 4, his condition had deteriorated from "serious but stable" to "critical".[10] On October 8, he died of Ebola.[11] The other three cases diagnosed in the United States as of October 2014[update] were:

- October 11, 2014, a nurse, Nina Pham, who had provided care to Duncan at the hospital.[12]

- October 14, 2014, Amber Joy Vinson, another nurse who treated Duncan.[13]

- October 23, 2014, physician Craig Spencer, diagnosed in New York City; he had just returned from working with Doctors Without Borders in Guinea, a country in West Africa.[14] He was treated at Bellevue Hospital in New York City.[15]

Hundreds of people were tested or monitored for potential Ebola virus infection,[16] but the two nurses were the only confirmed cases of locally transmitted Ebola. Public health experts and the Obama administration opposed instituting a travel ban on Ebola endemic areas, stating that it would be ineffective and would paradoxically worsen the situation.[17]

No one who contracted Ebola while in the United States died from it. No new cases were diagnosed in the United States after Spencer was released from Bellevue Hospital on November 11, 2014.[18]

Cases diagnosed in the U.S.

[edit]| Articles related to the |

| Western African Ebola virus epidemic |

|---|

|

| Overview |

| Nations with widespread cases |

| Other affected nations |

| Other outbreaks |

First case: Thomas Eric Duncan

[edit]Thomas Eric Duncan in Liberia

[edit]Thomas Eric Duncan was from Monrovia, Liberia, to date the country hit hardest by the Ebola virus epidemic.[19] He worked as a personal driver for the general manager of Safeway Cargo, a FedEx contractor in Liberia.[20] According to manager Henry Brunson, Duncan had abruptly quit his job on September 4, 2014, giving no reason.[21]

On September 15, 2014, the family of Marthalene Williams, who later died of Ebola virus disease, could not call an ambulance to transfer the pregnant Williams to a hospital. Duncan, their tenant, helped to transfer Williams by taxi to an Ebola treatment ward in Monrovia. Duncan rode in the taxi to the treatment ward with Williams, her father and her brother.[22]

On September 19, Duncan went to Monrovia Airport, where, according to Liberian officials, he lied about his history of contact with the disease on an airport questionnaire before boarding a Brussels Airlines flight to Brussels. In Brussels, he boarded United Airlines Flight 951 to Washington Dulles Airport.[23] From Dulles, he boarded United Airlines Flight 822 to Dallas/Fort Worth. He arrived in Dallas at 7:01 p.m. CDT[24] on September 20, 2014,[8][9] and stayed with his partner and her five children, who lived in the Fair Oaks apartment complex in the Vickery Meadow neighborhood of Dallas.[25][26] Vickery Meadow, the neighborhood in Dallas where Duncan lived, has a large African immigrant population and is Dallas's densest neighborhood.[27]

Duncan's illness in Dallas

[edit]

Duncan began experiencing symptoms on September 24, 2014, and arrived at the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital emergency room at 10:37 p.m. on September 25.[28] At 11:36 p.m., a triage nurse asked him about his symptoms, and he reported feeling "abdominal pain, dizziness, nausea and headache (new onset)".[28] The nurse recorded a fever of 100.1 °F (37.8 °C), but did not inquire as to his travel history as this was not triage protocol at the time.[28] At 12:05 a.m., Duncan was admitted into a treatment area room where the on-duty physician accessed the electronic health record (EHR). The physician noted nasal congestion, a runny nose, and abdominal tenderness. Duncan was given paracetamol (acetaminophen) at 1:24 a.m.[28] CT scan results came back noting "no acute disease" for the abdominal and pelvic areas and "unremarkable" for the head.[28] Lab results returned showing slightly low white blood cells, low platelets, increased creatinine, and elevated levels of the liver enzyme AST.[28][29] His temperature was noted at 103.0 °F (39.4 °C) at 3:02 a.m. and 101.2 °F (38.4 °C) at 3:32 a.m. Duncan was diagnosed with sinusitis and abdominal pain and sent home at 3:37 a.m. with a prescription for antibiotics, which are not effective for treating viral diseases.[28][30]

What we're seeing now is not an "outbreak" or an "epidemic" of Ebola in America. This is a serious disease, but we can't give in to hysteria or fear. – President Barack Obama on the Ebola outbreak

Duncan's condition worsened, and he was transported on September 28 to the same Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital emergency room by ambulance.[31][32] He arrived in the emergency room at 10:07 a.m., experiencing diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever.[33] Within fifteen minutes, a doctor noted that Duncan had recently come from Liberia and needed to be tested for Ebola. The doctor described following "strict [CDC] protocol" including wearing a mask, gown, and gloves. At 12:58 p.m., the doctor called the CDC directly. By 9:40 p.m., Duncan was experiencing explosive diarrhea and projectile vomiting.[33] At 8:28 a.m. the next morning, the doctor noted that he "appeared to be deteriorating". By 11:32 a.m., he was severely fatigued, enough to prevent him from using the bedside toilet.[33] Later that day, he was transferred to an intensive care unit (ICU) after all other patients had been evacuated. The next day, September 30, he was diagnosed with Ebola virus disease after a positive test result.[33]

Duncan's diagnosis was publicly confirmed during a CDC news conference the same day.[34][35] That evening, Duncan reported feeling better and requested to watch a movie. The following morning, he was breathing rapidly and complaining of "pain all over".[33] By the afternoon, however, he was able to eat, and the doctor noted that he was feeling better. The next day, October 3, he again reported feeling abdominal pain. That evening, the hospital contacted Chimerix, a biotechnology company developing Brincidofovir to combat the disease. The next day, Duncan's organs were failing, and he was intubated to help him breathe. In the afternoon, the hospital began administering Brincidofovir.[36][37] Nurses Nina Pham and Amber Joy Vinson continued to care for Duncan around the clock. On October 7, the hospital reported that Duncan's condition was improving.[38] However, he died at 7:51 a.m. on October 8, becoming the first person to die in the United States of Ebola virus disease and the index patient for the later infections of nurses Pham and Vinson.[39][40]

Contact tracing

[edit]On October 5, the CDC announced it had lost track of a homeless man who had been in the same ambulance as Duncan. They announced efforts were underway to find the man and place him in a comfortable and compassionate monitoring environment. Later that day, the CDC announced that the man had been found and was being monitored.[41]

Up to 100 people may have had contact with those who had direct contact with Duncan after he showed symptoms. Health officials later monitored 50 low- and 10 high-risk contacts, the high-risk contacts being Duncan's close family members and three ambulance workers who took him to the hospital.[42] Everyone who came into contact with Duncan was being monitored daily to watch for symptoms of the virus,[43] until October 20, when health officials removed 43 out of the 48 initial contacts of Thomas Duncan from isolation.[44] On November 7, 2014, Dallas was officially declared "Ebola free" after 177 monitored people cleared the 21 day threshold without becoming ill.[45]

Reactions

[edit]On October 2, Liberian authorities said they could prosecute Duncan if he returned because before flying he had filled out a form in which he had falsely stated he had not come into contact with an Ebola case.[46] Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation she was angry with Duncan for what he had done, especially given how much the United States was doing to help tackle the crisis: "One of our compatriots didn't take due care, and so, he's gone there and in a way put some Americans in a state of fear, and put them at some risk, and so I feel very saddened by that and very angry with him. ... The fact that he knew (he might be a carrier) and he left the country is unpardonable, quite frankly."[47] Before his death, Duncan brazenly claimed that he did not know at the time of boarding the flight that he had been exposed to Ebola; he said he believed the woman he helped was having a miscarriage, which contradicts corroborated accounts from family members who also helped transport the woman to an Ebola ward.[22][48]

Duncan's family said the care Duncan received was at best "incompetent" and at worst "racially motivated".[49] Family members threatened legal action against the hospital where Duncan received treatment.[50] In response, Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital issued a statement, "Our care team provided Mr. Duncan with the same high level of attention and care that would be given any patient, regardless of nationality or ability to pay for care. We have a long history of treating a multicultural community in this area."[51] The hospital spent an estimated $500,000 to treat the uninsured Duncan.[52]

Officials at Texas Presbyterian Hospital reported that patients' cancellation of elective surgeries and potential emergency patients' preference for other hospitals' emergency rooms had left their hospital looking like a "ghost town".[53]

The reaction to the care and treatment of Thomas Duncan, and the subsequent transmission to two of the nurses on his care team, caused several hospitals to question the extent to which they are obligated to treat Ebola patients. Their concern surrounds the reality that understaffed and poorly equipped hospitals performing invasive procedures, like renal dialysis and intubation, both of which Duncan received at Texas Presbyterian, could put staff at too much risk for contracting the virus. Emory University Hospital in Atlanta also used renal dialysis in treating patients at their biocontainment unit, but no health care workers became infected.[54] In October 2014 Vickery Meadow residents stated that people were discriminating against them because of the incident.[55]

Second case: Nina Pham

[edit]

On the night of October 10, Nina Pham, a 26-year-old nurse who had treated Duncan at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, reported a low-grade fever and was placed in isolation. On October 11, she tested positive for Ebola virus, becoming the first person to contract the virus in the U.S. On October 12, the CDC confirmed the positive test results.[12] Hospital officials said Pham had worn the recommended protective gear when treating Duncan on his second visit to the hospital and had "extensive contact" with him on "multiple occasions". Pham was in stable condition as of October 12.[12][56][57]

On October 16, Pham was transferred to the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland.[58] On October 24, the NIH declared Pham free of the Ebola virus.[59] That day Pham traveled to the White House where she met with President Obama.[60]

Controversies and lawsuit

[edit]Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, initially blamed a breach in protocol for the infection.[61] The hospital's chief clinical officer, Dr. Dan Varga, said all staff had followed CDC recommendations. Bonnie Costello of National Nurses United said, "You don't scapegoat and blame when you have a disease outbreak. We have a system failure. That is what we have to correct."[62] Frieden later spoke to "clarify" that he had not found "fault with the hospital or the healthcare worker".[63] National Nurses United criticized the hospital for its lack of Ebola protocols and for guidelines that were "constantly changing".[64] Briana Aguirre, a nurse who had cared for Nina Pham, criticized the hospital in an appearance on NBC's Today Show. Aguirre said that she and others had not received proper training or personal protective equipment, and that the hospital had not provided consistent protocols for handling potential Ebola patients into the second week of the crisis.[65] A report indicated that healthcare workers did not wear hazmat suits until Duncan's test results confirmed his infection due to Ebola, two days after his admission to the hospital.[66] Frieden later said that the CDC could have been more aggressive in the management and control of the virus at the hospital.[67]

On March 2, 2015 The New York Times reported that Pham filed a suit against Texas Health Resources, her hospital's parent company, accusing it of "negligence, fraud and invasion of privacy".[68] Pham was described as still experiencing numerous physical and psychological problems, listing lack of proper training as the reason for her illness.[68]

Third case: Amber Vinson

[edit]

On October 14, a second nurse at the same hospital, identified as 29-year-old Amber Vinson,[69] reported a fever. Amber Joy Vinson[70] was among the nurses who had provided treatment for Duncan. Vinson was isolated within 90 minutes of reporting the fever. By the next day, Vinson had tested positive for Ebola virus.[71] On October 13, Vinson had flown Frontier Airlines Flight 1143 from Cleveland to Dallas, after spending the weekend in Tallmadge and Akron, Ohio. Vinson had an elevated temperature of 99.5 °F (37.5 °C) before boarding the 138-passenger jet, according to public health officials. Vinson had flown to Cleveland from Dallas on Frontier Airlines Flight 1142 on October 10.[72] Flight crew members from Flight 1142 were put on paid leave for 21 days.[73]

During a press conference, CDC Director Tom Frieden stated she should not have traveled since she was one of the health care workers known to have had exposure to Duncan.[74] Passengers of both flights were asked to contact the CDC as a precautionary measure.[75][76][77]

It was later discovered that the CDC had, in fact, given Vinson permission to board a commercial flight to Cleveland.[78] Before her trip back to Dallas, she spoke to Dallas County Health Department and called the CDC several times to report her 99.5 °F (37.5 °C) temperature before boarding her flight. A CDC employee who took her call checked a CDC chart, noted that Vinson's temperature was not a true fever – a temperature of 100.4 °F (38.0 °C) or higher – which the CDC deemed as "high risk", and let her board the commercial flight.[79][80] On October 19, Vinson's family released a statement detailing her government-approved travel clearances and announcing that they had hired a Washington, DC, attorney, Billy Martin.[81] As a precaution, sixteen people[82] in Ohio who had had contact with Vinson were voluntarily quarantined. On October 15, Vinson was transferred to the Emory University Hospital in Atlanta.[83] Seven days later, Vinson was declared Ebola free by Emory University Hospital.[84]

Monitoring of other health care workers

[edit]As of October 15, 2014[update], there were 76 Texas Presbyterian Hospital health care workers being monitored because they had had some level of contact with Thomas Duncan.[85] On October 16, after learning that Vinson had traveled on a plane before her Ebola diagnosis, the Texas Department of State Health Services advised all health care workers exposed to Duncan to avoid travel and public places until 21 days after their last known exposure.[86]

Fourth case: Craig Spencer

[edit]On October 23, Craig Spencer,[14] a physician who treated Ebola patients in West Africa, tested positive for Ebola at Bellevue Hospital Center after having a 100.3 °F (37.9 °C) fever. Officials said he was hospitalized with fever, nausea, pain, and fatigue.[87] He had flown to New York City from Guinea within the previous ten days,[88] and contacted the city's Department of Health and Doctors without Borders after showing symptoms.[89][90] Dr. Spencer traveled to Guinea to treat Ebola victims on September 16 and returned on October 16. He had been self-monitoring for symptoms of the disease, and began to feel sluggish on October 21, but did not show any symptoms for two days.[91] His case was the first to be diagnosed in New York.[92] The city was trying to find people who may have been in contact with Dr. Spencer between October 21 and 23.[14]

On October 22, the day before he had symptoms, Dr. Spencer rode the New York City Subway, walked on the High Line park, went to a bowling alley and a restaurant in Brooklyn, took an Uber to his home in Manhattan, and took a 3-mile (4.8 km) jog in Harlem near where he lived.[93][94] Three other people who were with Dr. Spencer in the previous few days were quarantined as well.[95] Dr. Spencer's apartment and the bowling alley he went to were cleaned by hazmat company Bio Recovery Corporation.[96][97] Health officials stated it was unlikely that Dr. Spencer could have transmitted the disease through subway poles, hand railings, or via bowling balls.[98][99]

New York hospitals, health-workers, and officials had conducted weeks of drills and training in preparation for patients like Dr. Spencer. Upon arrival at the hospital, he was put in a specially designed isolation center for treatment. Not many details about the treatment were given, except that he participated in decisions relating to his medical care.[100] On October 25, the New York Post reported that an anonymous source had said that nurses at Bellevue had been calling in sick to avoid having to care for Spencer. A hospital spokesperson denied there was a sick out.[101] On November 1, his condition was upgraded to "stable",[102] and on November 7 the hospital announced he was free of Ebola.[103] Spencer was released from the hospital on November 11.[104] He was cheered and applauded by medical staff members, and hugged by the Mayor of New York, Bill de Blasio as he walked out of the hospital. The Mayor also declared: "New York City is Ebola free".[87]

As a result of Dr. Spencer's Ebola case, U.S. Senator Charles Schumer (D-NY), proposed an Ebola fund in an omnibus bill to be considered in fiscal year 2015. Schumer said the funds were needed to compensate New York City, as well as other cities treating Ebola patients, in the same way the federal government covers communities that suffer after a natural disaster. Schumer said Dr. Spencer's care at Bellevue Hospital involved around 100 health care workers. In addition, the city's health department established a 24-hour-a-day operation involving 500 staffers to keep track of the approximately 300 persons from West Africa hot spots who arrive in New York every day.[105]

Medical evacuations from West Africa

[edit]

By the time the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa was over in June 2016, seven Americans had been evacuated to the U.S. for treatment after contracting Ebola virus while working with medical teams trying to stop the epidemic.[106] Kent Brantly, a physician and medical director in Liberia for the aid group Samaritan's Purse, and co-worker Nancy Writebol were infected in July 2014, while working in Monrovia.[107][108][109] Both were flown to the United States at the beginning of August via the CDC's Aeromedical Biological Containment System for further treatment in Atlanta's Emory University Hospital.[110] On August 21, Brantly and Writebol recovered and were discharged.[111] Brantly has since donated blood to three others with Ebola (Sacra, Mukpo and Pham).[citation needed]

On September 4, a Massachusetts physician, Rick Sacra, was airlifted from Liberia to be treated in Omaha, Nebraska at the Nebraska Medical Center. Working for Serving In Mission (SIM), he was the third U.S. missionary to contract Ebola.[112] He thought that he probably contracted Ebola while performing a Caesarean section on a patient who had not been diagnosed with the disease. While in hospital, Sacra received a blood transfusion from Brantly, who had recently recovered from the disease. On September 25, Sacra was declared Ebola-free and released from the hospital.[113]

On September 9, the fourth U.S. citizen who contracted the Ebola virus arrived at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta for treatment. On October 16, he released a statement saying he had improved and expected to be discharged in the near future. The doctor was identified as Ian Crozier, and according to the hospital, the sickest patient treated.[114][115][116] He was scheduled to receive a blood or serum transfusion from a British man who had recently recovered from the disease.[117] In addition, on September 21, a CDC employee, who showed no symptoms of the disease, was flown back to the United States as a preventive measure after low-risk exposure with a healthcare worker; he posed no risks to his family or the United States, and he is not known to have died.[118] On September 28, a fourth American doctor was admitted to National Institutes of Health hospital.[119]

On October 2, NBC News photojournalist Ashoka Mukpo, covering the outbreak in Liberia, tested positive for Ebola after showing symptoms.[120] Four other members of the NBC team, including physician Nancy Snyderman, were being closely monitored for symptoms.[121] Mukpo was evacuated on October 6 to the University of Nebraska Medical Center for treatment in their isolation unit.[106] On October 21, Mukpo was declared Ebola-free and allowed to return to his home in Rhode Island.[122]

A government official in Sierra Leone announced on November 13, that a doctor from Sierra Leone, a permanent resident of the United States married to a U.S. citizen, would be transported to the Nebraska Medical Center for treatment for Ebola.[123][124] The doctor, identified later as Martin Salia, became symptomatic while in Sierra Leone. His initial Ebola test came back negative, but his symptoms persisted. He attempted to treat his symptoms, which included vomiting and diarrhea, believing he had malaria. A second test for Ebola came back positive. His family expressed concern that the delay in diagnosis might have impacted his recovery.[125] Salia arrived at Eppley Airfield in Omaha on November 15, and was transported to the Nebraska Medical Center. According to the team that assisted in the transport, he was critically ill and considered to be the sickest patient to be evacuated, but stable enough to fly.[126] On November 17, Salia died from the disease. Dr. Philip Smith, medical director of the biocontainment unit at Nebraska Medical Center, said Salia's disease was already "extremely advanced" by the time he arrived in Omaha. By then, Salia's kidneys had failed and he was in acute respiratory distress. Salia's treatment included a blood plasma transfusion from an Ebola survivor, as well as the experimental drug ZMapp. Salia had been working as a general surgeon in Freetown, Sierra Leone when he fell ill. It was not clear when or where he had had contact with Ebola patients.[127]

A U.S. clinician contracted Ebola while working in Port Loko, Sierra Leone. He collapsed in the hospital and colleagues who assisted him were monitored for exposure. He was diagnosed with Ebola on March 10, 2015, and medically evacuated to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland on March 13.[128] His condition was downgraded from serious to critical on March 16.[129] The ten exposed colleagues were flown back to the U.S., going into isolation near the Ebola-rated hospitals at Nebraska, Georgia, and Maryland.[130] On March 26, 2015, the NIH upgraded the medically evacuated health worker being treated in Bethesda from critical to serious. A further 16 volunteers were monitored for possible exposure.[131] On April 9, 2015, the clinician was upgraded to good condition and discharged.[132] He was treated by Dr. Anthony Fauci, who later said he was "the sickest person he had ever treated, who recovered." This patient wished to remain anonymous until late 2019, when he revealed his identity: Preston Gorman, a physician assistant. [133][134]

Containment efforts

[edit]Operation United Assistance

[edit]

The U.S. military released plans to send up to 4,000 troops to West Africa to establish treatment centers starting September 29. The troops are tasked with building modular hospitals known as Expeditionary Medical Support Systems (EMEDS). Plans included building a 25-bed hospital for health care workers and 17 treatment centers with 100 beds each in Liberia.[135] By the end of September 2014 150 military personnel were helping USAID in the capital, Monrovia.[136]

U.S. Army chief of staff Ray Odierno ordered on October 27 a 21-day quarantine of all soldiers returning from Operation United Assistance. Up to 12 soldiers were quarantined in a U.S. base in Italy.[137]

Revised CDC guidelines

[edit]Since 2007, US hospitals have relied on CDC infection control protocols to contain Ebola virus disease. Until October 20, 2014, the CDC guidelines allowed hospitals wide latitude to select gear based on interaction between healthcare workers and patients and on the mode of transmission of the disease being handled. The guidelines suggested gowns with "full coverage of the arms and body front, from neck to the mid-thigh or below, will ensure that clothing and exposed upper body areas are protected", and additionally recommend masks and goggles.[138][139]

Some infection control experts[who?] said that many American hospitals improperly trained their personnel to handle Ebola cases because they were following federal guidelines that were too lax. US officials abruptly changed their guidelines on October 14. The New York Times stated that this was an effective acknowledgment that there were problems with the procedures for protecting health care workers. Sean Kaufman, who oversaw infection control at Emory University Hospital while it treated Ebola patients, has said the previous CDC guidelines were "absolutely irresponsible and dead wrong". Kaufman called to warn the agency about its lax guidelines but, according to Kaufman, "They kind of blew me off."[140]

A Doctors Without Borders representative, whose organization has been treating Ebola patients in Africa, criticized a CDC poster for lax guidelines on containing Ebola, saying, "It doesn't say anywhere that it's for Ebola. I was surprised that it was only one set of gloves, and the rest bare hands. It seems to be for general cases of infectious disease."[140]

The national nursing union National Nurses United criticized the CDC for making the guidelines voluntary. There were complaints at the Texas hospital that healthcare professionals had to use tape to cover their exposed necks.[140] According to Frieden, the CDC is appointing a hospital site manager to oversee Ebola containment efforts and are making "intensive efforts" to retrain and supervise staff.[138]

On October 14, the WHO reported that 125 contacts in the United States were being traced and monitored.[141] On October 20, the CDC updated its guidance on personal protective equipment with new detailed instructions that include specifying that no skin should be exposed and adding extensive instructions for donning and doffing the equipment.[142] On October 20 CDC updated its guidance to add clarification that Ebola may spread through wet droplets such as sneezes.[143][144][145]

Ebola response coordinator

[edit]In mid-October 2014, President Barack Obama appointed Ron Klain as the "Ebola response coordinator" of the United States. Klain is a lawyer who previously served as chief of staff to vice presidents Al Gore and Joe Biden.[146] Klain had no medical or health care experience.[147] After criticism, Obama said, "It may make sense for us to have one person ... so that after this initial surge of activity, we can have a more regular process just to make sure that we're crossing all the T's and dotting all the I's going forward". Klain reported to Homeland Security Adviser Lisa Monaco and National Security Advisor Susan Rice.[148][149][150][151] Klain did not coordinate with hospitals and the United States Public Health Service, as this was the responsibility of Nicole Lurie, Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response.[152] President Barack Obama attempted to calm public fears by hugging nurse Nina Pham who had been cured of Ebola.[153]

Rapid response teams

[edit]President Obama announced the formation of rapid response teams to travel to hospitals with newly diagnosed patients. A second set of teams will prep hospitals in cities deemed most likely to see an Ebola virus case. Three of those teams are already operating. In announcing the formation of the teams, President Obama explained, "We want a rapid response team, a SWAT team essentially, from the CDC to be on the ground as quickly as possible, hopefully within 24 hours, so that they are taking the local hospital step by step through what needs to be done." The CDC has developed two sets of teams, identified by the acronyms CERT (CDC Ebola Response Team) and FAST (Facility Assessment and Support Teams). The CERTs have 10 to 20 people each, who can be sent to a hospital with a suspected and/or laboratory confirmed Ebola virus case. The teams are drawn from 100 CDC workers and others. The FAST teams assist hospitals that have indicated they are willing to take on Ebola cases.[154]

Airport screening

[edit]

Starting in October 2014, U.S. government officials began questioning airplane passengers and screening them for fever at five U.S. airports: John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York, Newark Liberty International Airport in New Jersey, O'Hare International Airport in Illinois, Washington Dulles International Airport in Virginia, and Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport in Georgia.[155] Combined, these airports receive more than 94% of passengers from Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, the three countries most affected by Ebola.[155][156]

Although no plans have been announced for other airports, screening in the U.S. represents a second layer of protection since passengers are already being screened upon exiting these three countries. However, the risk can never be eliminated.[157] On October 21, the Department of Homeland Security announced that all passengers from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea will be required to fly into one of these five airports.[158] On October 23, the CDC announced that all passengers from these countries would receive 21-day monitoring.[159]

A physician with the WHO, Aileen Marty, who had spent 31 days in Nigeria, criticized the complete lack of screening for Ebola on her recent return to the United States through Miami International Airport on October 12.[citation needed]

There have also been calls by congressional leaders, including U.S. representative Ed Royce, Chairman of the House Foreign Relations Committee, and U.S. representative Michael McCaul of Texas, Chair of the Homeland Security Committee, to suspend issuing visas to travelers from the affected West African countries, including Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea.[160][161]

Mandatory 21-day quarantine

[edit]

On October 7, 2014, Connecticut governor Dannel Malloy signed an order authorizing the mandatory quarantine for 21 days of anyone, even if asymptomatic, who had direct contact with Ebola patients.[162][163] Nine people were quarantined on October 22, in accordance with the Connecticut order.[164]

At a joint news conference on October 24, New York governor Andrew Cuomo and New Jersey governor Chris Christie announced that they were imposing a mandatory 21-day quarantine on all air travelers returning to New York and New Jersey from West Africa who have had contact with Ebola patients. In explaining the move from the CDC's voluntary quarantine to a state ordered mandatory one, Cuomo cited the case of Dr. Spencer. "In a region like this, you go out three times, you ride the subway, you ride the bus, you could affect hundreds of people." Cuomo praised Dr. Spencer's work but stated, "He's a doctor and even he didn't follow the voluntary quarantine. Let's be honest."[165][166]

Governors Cuomo and Christie stated that their two states needed to go beyond the federal CDC guidelines. Cuomo said Dr. Spencer's activity in the days before his diagnosis showed the guidelines, which includes urging health care workers and others who have had contact with Ebola patients to voluntarily quarantine themselves, were not enough.[165]

Late on October 26, Cuomo modified the state's quarantine procedure, stating that people entering New York who have had contact with Ebola patients in West Africa will be quarantined in their homes for the 21 days, with twice daily checks to ensure their health has not changed and that they are complying with the order, and would receive some compensation for lost wages, if any.[167] President Obama and his staff had been attempting to persuade Cuomo, Christie, and the government of Illinois[168] to reverse their mandatory quarantines.[167]

Illinois governor Pat Quinn issued a similar quarantine authorization the same day as New York and New Jersey initially did, with Florida governor Rick Scott on October 25, authorizing mandatory twice daily monitoring for 21 days of people identified as coming from countries affected by Ebola.[169][170] Illinois health officials later said that only people at high risk of Ebola exposure, such as not wearing protective gear near Ebola patients, will be quarantined.[171]

Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Georgia have all authorized mandatory twice daily health monitoring and/or temperature reporting for 21 days for people exposed to people with Ebola. Virginia has also implemented mandatory twice daily temperature reporting and daily monitoring from health authorities, but has also authorized mandatory quarantine for higher risk patients.[172][173] California mandated a 21-day quarantine for all health workers who have had contact with Ebola patients.[174]

Kaci Hickox, an American nurse who treated Ebola patients in Sierra Leone became the first person placed under the new mandatory quarantine rules on her arrival at Newark Liberty International Airport, in New Jersey. A low-accuracy (forehead) thermometer indicated Hickox developed a fever on Friday night and was taken to University Hospital in Newark. She later tested negative for the Ebola virus but remained quarantined in a medical tent. Hickox and Doctors Without Borders criticized the condition of the quarantine in a tent with a bed and a portable toilet, but without shower facility.[175] Hickox expressed that it was inhumane.[176] The hospital responded that they tried their best to accommodate Hickox by allowing her to have computer access, cell phone, reading materials, and providing take-out food and drink.[177] On October 27, after being symptom free for an additional 24-hour period, testing negative for Ebola, and after the state's quarantine policy was relaxed the night before,[167] Hickox was released from quarantine in New Jersey.[178] She has filed suit.[179]

Hickox was escorted out of New Jersey and into Maine the following day by a private convoy of SUVs.[180] Maine governor Paul LePage announced he was joining with his state's health department in seeking legal authority to enforce the quarantine after Hickox announced she would not comply with the isolation protocols in Maine. She left her house on October 29 and 30.[181] The governor said: "She's violated every promise she's made so far, so I can't trust her. I don't trust her."[182] A Maine judge ruled against a mandatory quarantine on October 31, but required Hickox to comply with "direct active monitoring", to coordinate her travel with Maine health officials, and to notify health officials if she develops symptoms of Ebola.[183]

On October 29, Texas governor Rick Perry announced that a Texas nurse returning from Sierra Leone where she treated Ebola patients, had agreed to self-quarantine at her Austin home for 21 days following her return to Texas, and undergo frequent monitoring from state health officials. although she did not have any symptoms of Ebola virus. The nurse was not named to protect her privacy. Perry spoke with the nurse over the phone to thank her for work to fight Ebola.[184]

U.S. Army Chief of Staff Ray Odierno also ordered on October 27 a 21-day quarantine of all soldiers returning from Operation United Assistance in Liberia. Up to 12 soldiers have been quarantined so far in a U.S. base in Italy.[185]

Legal protection for government contractors

[edit]On November 13, 2014, President Obama issued a presidential memorandum, invoking a federal law to immunize contractors hired by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) from liability "with respect to claims, losses, or damage arising out of or resulting from exposure, in the course of performance of the contracts, to Ebola" during the emergency period.[186]

School closures

[edit]There were numerous overreactions to the perceived threat of an Ebola outbreak, particularly on the part of school officials. On October 16, a building housing two schools in the Solon City School District near Cleveland, Ohio, was closed for a single day of disinfection procedures after finding that a staff member may have been on the aircraft that Amber Vinson used on a previous flight.[187] Another school in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District was disinfected overnight due to similar concerns but remained open. In both cases, affected staff were sent home until cleared by health officials. School officials said that they had been assured by city health officials that there was no risk and that the disinfection was "strictly precautionary".[188] Three schools in the Belton Independent School District in Belton, Texas, were also closed. Infectious disease experts considered these closures to be an overreaction and were concerned that it would frighten the public into believing that Ebola is a greater danger than it actually is.[189]

In Hazlehurst, Mississippi, in response to numerous parents keeping their children from attending school, a principal at Hazlehurst Middle School, agreed to take personal vacation time after he had traveled to Zambia, a country with no current Ebola cases and 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometres) away from West Africa.[190][191]

Treatment

[edit]Biocontainment units in the U.S.

[edit]

The United States has the capacity to isolate and manage 11 patients in four specialized biocontainment units. These include the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, Nebraska, the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, St. Patrick Hospital and Health Sciences Center in Missoula, Montana and Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia.[120][194][195][196]

Experimental treatments

[edit]There is as yet no medication for Ebola approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Dr. Anthony Fauci, has stated that the scientific community is still in the early stages of understanding how infection with the Ebola virus can be treated and prevented.[197] There is no cure or specific treatment that is currently approved.[198] However, survival is improved by early supportive care with rehydration and symptomatic treatment. Treatment is primarily supportive in nature.[199] A number of experimental treatments are being considered for use in the context of this outbreak, and are currently or will soon undergo clinical trials.[200][201]

In late August 2014, both Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol became the first people to be given the experimental drug ZMapp. They both recovered, but there was no confirmation or proof that the drug was a factor.[202] A Spanish priest with Ebola had taken ZMapp but died afterward.[203] Up until that time, ZMapp had only been tested on primates and looked promising, causing no serious side effects and protecting the animals from infection.[204] The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has donated $150,000 to help Amgen increase its production, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has asked a number of centers to also increase production.[205]

There have been at least two promising treatments for those already infected. The first is brincidofovir, an experimental antiviral drug, which was given to Duncan, Mukpo, and Spencer.[206]

Treatment using a transfusion of plasma from Ebola survivors, a form of "passive immunotherapy",[207] since it contains antibodies able to fight the virus, has been used with apparent success on a number of patients.[204] Survivor Kent Brantly donated his blood to Rick Sacra, Ashoka Mukpo and nurse Nina Pham.[208][209] The World Health Organization (WHO) has made it a priority to try the treatment, and has been telling affected countries how to do it.[210]

Experimental preventive vaccines

[edit]Many Ebola vaccine candidates had been developed in the decade before 2014, but none has yet been approved for clinical use in humans.[211] Several promising vaccine candidates have been shown to protect nonhuman primates (usually macaques) against lethal infection, and some are now going through the clinical trial process.[212][213]

In late October 2014, Canada planned to ship 800 vials of an experimental vaccine to the WHO in Geneva, the drug having been licensed by NewLink Genetics Corporation, of Iowa. British drugmaker GlaxoSmithKline also announced it had expedited research and development of a vaccine, which, if successful, could be available in 2015.[214] Although it's still unknown which ones will be approved, WHO hopes to have millions of vaccine doses ready sometime in 2015, and expects that five more experimental vaccines will start being tested in March 2015.[215]

In December 2019, the first Ebola vaccine was approved.[216] rVSV-ZEBOV, otherwise known as Ervebo, is a vaccine for adults that prevents the Zaire ebolavirus.[217]

Public reactions

[edit]In October 2014, Navarro College, a two-year public school located in Texas, received media attention for admission rejection letters sent to two prospective students from Nigeria. The letters informed the applicants that the college was "not accepting international students from countries with confirmed Ebola cases".[218] On October 16, Navarro's Vice-President Dewayne Gragg issued a statement confirming that there had indeed been a decision to "postpone our recruitment in those nations that the Center for Disease Control and the U.S. State Department have identified as at risk".[219] Nigeria's outbreak was among the least severe in West Africa and was considered over by the WHO on October 20; the Nigerian health ministry had previously announced on September 22 that there were no confirmed cases of Ebola within the country.[citation needed]

In October 2014, the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University withdrew an invitation it had extended to Pulitzer Prize winning photojournalist Michel du Cille because he'd returned three weeks earlier from covering the Ebola outbreak in Liberia.[220][221] In October 2014, Case Western Reserve University withdrew their speaking invitation to Dr. Richard E. Besser, chief health editor at ABC News and former director of the CDC. Besser had recently returned from a trip to Liberia.[221][222][223]

On October 17, Harvard University imposed limits on travel to Ebola-affected countries (Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia) for its students, staff, and faculty. All travel to these countries is "strongly discourage[d]", and such travel as part of a Harvard program requires approval from the provost.[224]

On October 25, CDC allowed state and local officials to set tighter control policies and Barbara Reynolds, a CDC spokeswoman released a statement saying "we will consider any measures that we believe have the potential to make the American people safer".[225] On November 1, Ohio tightened restrictions on people travelling to Western African countries impacted by Ebola.[226]Time magazine's 2014 Person of the Year issue honored health professionals dedicated to fighting Ebola, including Kent Brantly.[227]

On October 28, future president Donald Trump tweeted that governors backing off from the Ebola quarantine would lead to more mayhem.[228] In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, these tweets were contrasted with Trump's then-opposition to mandatory quarantines.[228]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Duncan contracted Ebola in Liberia and was diagnosed in the U.S.

- Two of the victims had had direct contact with Duncan.

- One victim was diagnosed in New York City; his case is unrelated to the Texas cases.

- ^ a b This takes into account the seven Americans who were medically evacuated from West Africa with Ebola.

References

[edit]- ^ "Who are the American Ebola patients?", CNN, October 6, 2014

- ^ "Ebola-Stricken Surgeon Martin Salia Died Despite ZMapp, Plasma Transfusion". ABC News. November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ^ "2014 Ebola Outbreak – Case Count". CDC. December 15, 2014. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "2014-2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 8, 2019. Archived from the original on June 1, 2018. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "First diagnosed case of Ebola in the U.S." CNN. September 30, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ CDC confirms first ever Ebola case in United States, cdc.gov; accessed October 9, 2014.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny; Philipps, Dave (October 9, 2014). "Death of Thomas Eric Duncan in Dallas Fuels Alarm Over Ebola". The New York Times. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Fernandez, Manny; Onishi, Norimitsu (October 1, 2014). "U.S. Patient Aided Ebola Victim in Liberia". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Thomas Eric Duncan: From healthy to Ebola". WYFF4. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ "First US Ebola case Thomas Duncan 'critical'". BBC News. October 4, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "Texas Ebola patient dies". CNN. October 8, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c Fernandez, Manny (October 12, 2014). "Texas Health Worker Tests Positive for Ebola". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ "Ebola outbreak: Second Texas health worker 'tests positive'". BBC News. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c "New York Doctor Just Back From Africa Has Ebola". NBC News. October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Santora, Marc (October 23, 2014). "Doctor in New York City Is Sick With Ebola". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Dan Diamond (October 20, 2014). "Maps: Who's Been Exposed To Ebola In The U.S. And Where They're Being Treated". Forbes. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ Mouawad, Jad (October 17, 2014). "Experts Oppose Ebola Travel Ban, Saying It Would Cut Off Worst-Hit Countries". The New York Times. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ "NYC doctor heads home, Ebola free". www.cbsnews.com. November 11, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Ebola Weakens Liberia Food Security". VOA. September 23, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ "Liberia says Dallas Ebola patient lied on exit documents". USA Today. October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (October 1, 2014). "Liberian Officials Identify Ebola Victim in Texas as Thomas Eric Duncan". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Thomas Eric Duncan timeline", The New York Times; accessed October 8, 2014.

- ^ "Ebola Patient in Dallas Lied on Screening Form, Liberian Airport Official Says", The New York Times, October 2, 2014

- ^ "History ✈ United #822 ✈ FlightAware". FlightAware. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- ^ Frosch, Dan (October 2, 2014). "Dallas Man Tells of U.S. Ebola Patient's Decline". WSJ. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "Retracing the Steps of the Dallas Ebola Patient". The New York Times. October 1, 2014.

- ^ "Vickery Meadow neighborhood is 'melting pot of America'" (Archive). The Dallas Morning News. October 11, 2014. Updated October 12, 2014. Retrieved on July 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Congressional committee releases timeline detailing how Presbyterian treated Ebola patient Thomas Eric Duncan". The Dallas Morning News. October 17, 2014. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ "Notable Elements of Mr. Duncan's Initial Emergency Department Visit" (PDF). US Congress. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ Berman, Mark (October 1, 2014). "Texas Ebola patient told hospital of travel from West Africa but was released". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ Gilblom, Kelly (October 3, 2014). "Electronic-Record Gap Allowed Ebola Patient to Leave Hospital". Bloomberg. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ "Dallas hospital says Ebola patient denied being around sick people". Los Angeles Times. October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Details of Duncan's Treatment Reveal a Wobbly First Response to Ebola". The New York Times. October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ "Ebola in the US – Ebola in Dallas". 2014 Ebola Outbreak. Archived from the original on October 13, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ Maggie Fox (October 2014). "How Did The Ebola Patient Escape for Two Days?". NBC News. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ "Dallas Ebola Patient Receives Experimental Drug". The Huffington Post. October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ "Chimerix Announces Emergency Investigational New Drug Applications for Brincidofovir Authorized by FDA for Patients With Ebola Virus Disease". Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ Sifferlin, Alexandra (October 7, 2014). "Dallas Ebola Patient Improves Slightly". Time. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "Texas Ebola Patient Thomas Eric Duncan Has Died". ABC News. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "Cases of Ebola Diagnosed in the United States". CDCP. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ "Found: Homeless Man Sought in Ebola Case Being Monitored". NBC News. October 5, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ "10 people at 'high risk' for Ebola as 50 people monitored daily after contact with Dallas Ebola patient". New York Daily News. October 3, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ "Hospital: Dallas Ebola patient in critical condition". CNN. October 4, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ Phillip, Abby (October 20, 2014). "Dallas officials plead for compassion, not stigma as 43 leave Ebola isolation". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Rice, Chelsea; Levingston, Katie; Allison, Meghan. "Ebola Today: Dallas is Officially Ebola-Free; Fewer Americans Googling Ebola". The Boston Globe. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "Liberia to Prosecute Man Who Brought Ebola to United States". NBC News. October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ "Liberian President criticizes Ebola patient in Dallas". CNN. October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ Selk, Avi (October 8, 2014). "Before his death, Duncan said he mistook Ebola case in Liberia for miscarriage; never lied". Dallas News. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "Ebola Outbreak and Outcry: Saving Thomas Eric Duncan". The Huffington Post. October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "Family of Thomas Eric Duncan says his death from Ebola is 'racially motivated'". WGN-TV. October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "Dallas' Ebola patient waited days for experimental drug". CNN. October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Ebola Victim Thomas Eric Duncan's 9-Day Treatment Cost Hospital Estimated $500K and He Had No Insurance, The Christian Post, October 10, 2014; accessed October 27, 2014.

- ^ ABC News. "Dallas Hospital 'Feels Like a Ghost Town' in Wake of Ebola Cases". ABC News.

- ^ "Some U.S. hospitals weigh withholding care to Ebola patients". Reuters. October 22, 2014.

- ^ Hunt, Dianna and Diane Solís. "Dallas' Vickery Meadow residents enduring backlash over Ebola" (Archive). The Dallas Morning News. October 6, 2014. Retrieved on July 20, 2015.

- ^ "Ebola: Texas nurse tests positive". CNN. October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ Ebola: Health care worker tests positive at Texas hospital. BBC News October 12, 2014.

- ^ "Nurse with Ebola heads to Maryland for care". USA Today. October 16, 2014.

- ^ "Virus Free: Ebola-Infected Nurse Nina Pham to Go Home". NBC News. October 24, 2014.

- ^ "Nina Pham, Free of Ebola", The New York Times, October 25, 2014.

- ^ Phillip, Abby (October 12, 2014). "CDC confirms second Ebola case in Texas. Health worker wore 'full' protective gear". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. CDC head criticized for blaming 'protocol breach' as nurse gets Ebola" Archived October 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Tribune, October 13, 2014.

- ^ "Fort Worth Alcon worker exposed to Ebola". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ "Nurses' union slams Texas hospital for lack of Ebola protocol". CNN. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ Lauer, Matt (October 16, 2014). "Dallas nurse Briana Aguirre". Today. ABC. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ "Was CDC Too Quick To Blame Dallas Nurses In Care Of Ebola Patient?". NPR.org. October 24, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ "Second Health Care Worker With Ebola Was In Isolation Within 90 Minutes: Official". Huffington Post. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Richard Perez-Pena, "Nurse Who Contracted Ebola in the U.S. Sues Her Hospital Employer". The New York Times. Retrieved on March 3, 2015.

- ^ "Second Ebola-infected nurse ID'd; flew domestic flight day before diagnosis". Fox News. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ Justin Ray (October 18, 2014). "What We Know About Amber Joy Vinson, 2nd Dallas Nurse Diagnosed With Ebola". KXAS-TV NBC5 DFW.

- ^ "Second Health Care Worker Tests Positive for Ebola". Texas Department of State Health Services. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ Berman, Mark (October 15, 2014). "Health-care worker with Ebola flew on commercial flight a day before being diagnosed". The Washington Post.

- ^ Jack Healy; Sabrina Tavernise; Abby Goodnough (October 16, 2014). "Obama May Name 'Czar' to Oversee Ebola Response". The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Perez, Chris (October 15, 2014). "Dallas nurse with Ebola should not have been traveling: CDC". New York Post. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ "CDC and Frontier Airlines Announce Passenger Notification Underway – Media Statement". CDC. January 2016.

- ^ "The Second Ebola Nurse Was On Commercial Flights And Now The CDC Is Looking For The Other Passengers". Business Insider. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ "Health-care worker with Ebola visited family in Summit County, traveled to Dallas from Cleveland". www.ohio.com. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ "Ebola nurse got CDC OK for Cleveland trip". October 15, 2014. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ "CDC: Ebola Patient Traveled By Air With 'Low-Grade' Fever". CBS News. October 15, 2014.

- ^ Raab, Lauren (October 19, 2014). "Ebola patient Amber Vinson's family disputes CDC story, gets a lawyer". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ WKYC Staff, WKYC (October 20, 2014). "Amber Vinson's family releases updated statement".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Amber Joy Vinson's stepfather under strict Ebola quarantine, 16 Ohioans had contact with Vinson". cleveland.com. October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ "Second Nurse With Ebola Arrives at Emory". ABC News. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ "Nurse Amber Vinson free of Ebola virus, family says". Yahoo News. October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "Ebola outbreak in the U.S., by the numbers". NJ.com. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Movement of Persons with Possible Exposure to Ebola". Texas Department of State Health Services. October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Shimon Prokupecz; Catherine E. Shoichet (November 10, 2014). "New York doctor now Ebola free, will be released from hospital". CNN.

- ^ Susman, Tina (October 23, 2014). "Manhattan doctor tests positive for Ebola". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "Patient at New York City hospital tests positive for Ebola, reports say". Fox News. October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Alchindor, Yaminche (October 23, 2014). "Ebola hits New York City". USA Today. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Marc Santora (October 23, 2014). "Doctor in New York City Tests Positive for Ebola". The New York Times. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Phillip, Abby (October 23, 2014). "New York City physician tests positive for Ebola". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Ellis, Jonathan (October 24, 2014). "Timeline of Everywhere the NYC Ebola Patient Went During His 'Self-Isolation'". Mashable. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ "New York Ebola case no cause for alarm, mayor says". CNN. October 24, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ "After 1st Ebola case in NYC, 3 others quarantined". NW Georgia News. Associated Press. October 24, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Laura Davison; Sonali Basak; Madeline McMahon (October 25, 2014). "Bio-Recovery Leads Cleanup of Ebola Spaces in New York". Bloomberg. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ Mueller, Benjamin (October 27, 2014). "For Crew in New York, Ebola Virus Is Fought With Scrub Brushes and Cleanser". The New York Times.

- ^ Donald G. McNeil Jr. (October 3, 2014). "Ask Well: How Does Ebola Spread? How Long Can the Virus Survive?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Donald G. McNeil Jr. (October 23, 2014). "Can You Get Ebola From a Bowling Ball?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Melanie Grey West (November 11, 2014). "Dr. Craig Spencer, New York Ebola Patient, Is Released". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Schram, Jamie; Celona, Larry (October 25, 2014). "Bellevue staffers call in 'sick' after Ebola arrives". New York Post.

- ^ Queally, James (November 1, 2014). "NYC Ebola patient improves; Oregon patient is 'low-risk' for virus". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ Hartocollis, Anemona (November 10, 2014). "Craig Spencer, New York Doctor With Ebola, Will Leave Bellevue Hospital". The New York Times.

- ^ Malo, Sebastien (November 11, 2014). "Update 1-New York doctor now free of Ebola discharged from hospital". Reuters. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ Perez, Chris (November 16, 2014). "Schumer to Obama: Reimburse NYC for $20M Ebola treatment". New York Post.

- ^ a b "Journalist With Ebola Being Evaluated at US Hospital", Voice of America, October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Two Americans Stricken With Deadly Ebola Virus in Liberia". July 28, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "Ebola outbreak: U.S. missionary Nancy Writebol leaves Liberia Tuesday". CBC News. August 4, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ "Ebola drug likely saved American patients". CNN.com. August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ Steenhuysen, Julie. "Ebola patient coming to U.S. as aid workers' health worsens". MSN News. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ "American Ebola doc: 'I am thrilled to be alive'". Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- ^ "A Third US missionary with Ebola virus leaves Liberia". The Daily Telegraph. London. September 5, 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ "American Doctor With Ebola Is 'Grateful' Following Release From Hospital". ABC News. September 25, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Grady, Denise (December 7, 2014). "An Ebola Doctor's Return From the Edge of Death". The New York Times. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ du Lac, J. Freedom (October 15, 2014). "Little mentioned patient at Emory expects to be discharged very soon free from the Ebola virus". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Ebola patient arrives at Atlanta hospital". WCVB Boston. September 9, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- ^ Addison, Stephen (September 18, 2014). "British Ebola survivor flies to United States for blood donation". Reuters. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ "2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa-September 25, 2014". CDC. September 25, 2014. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- ^ Maggie Fox. "Possible Ebola Patient Arrives at U.S. NIH Lab". NBC News. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "US Journalist Believes He Got Ebola While Cleaning Infected Car", ABC News, October 6, 2014

- ^ "US cameraman tests positive for Ebola". News24. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Alex (October 21, 2014). "NBC News Freelancer Ashoka Mukpo Declared Free of Ebola". NBC News. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ Elizabeth Cohen, Senior Medical Correspondent (November 14, 2014). "Ebola patient from Sierra Leone heading to Nebraska". CNN.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Ebola outbreak: Doctor infected in Sierra Leone to be treated in Omaha, Nebraska". CBS News. November 13, 2014.

- ^ Sieff, Kevin (November 17, 2014). "A doctor's mistaken Ebola test: 'We were celebrating. ... Then everything fell apart'". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Martin Salia, Surgeon With Ebola, Arrives in Nebraska From Sierra Leone". The New York Times. November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ^ Goodnough, Abby; Trenchard, Tommy (November 17, 2014). "Doctor Being Treated for Ebola in Omaha Dies". The New York Times.

- ^ Fink, Sheri (March 13, 2015). "U.S. Clinician With Ebola Under Care in Maryland", The New York Times.

- ^ Doctors treating patient with Ebola at NIH downgrade condition to critical, The Washington Post, Brady Dennis, March 16, 2015

- ^ Americans exposed to Ebola patient return from Africa for monitoring, Elizabeth Cohen, CNN, March 16, 2015

- ^ Sifferlin, Alexandra (March 26, 2015). "American Patient With Ebola Has Condition Upgraded". Time. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ "Patient admitted with Ebola virus disease discharged from NIH Clinical Center". National Institutes of Health (NIH). July 20, 2015.

- ^ "He survived Ebola—but the worst was yet to come".

- ^ "PA Diagnosed with Ebola Suffers Trauma After Long Isolation". April 2020.

- ^ du Lac, J. Freedom (October 13, 2014). "The U.S. military's new enemy: Ebola. Operation United Assistance is now underway". The Washington Post.

- ^ "News Archive". U.S. Department of Defense.

- ^ ABC News. "US Army to Quarantine Troops Who Were Fighting Ebola". ABC News.

- ^ a b "With Ebola cases, CDC zeros in on lapses in protocol, protective gear". Los Angeles Times. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ "Element IV: Personal Protective Equipment". Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c McNeil, Donald G. Jr (October 16, 2014). "Lax U.S. guidelines on Ebola led to poor hospital training, experts say". The New York Times.

- ^ Ebola Response Roadmap Update-October 15, 2014, World Health Organization, who.int.

- ^ "Procedures for PPE". www.cdc.gov. CDC. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Hospitalized Patients with Known or Suspected Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever in U.S. Hospitals – Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever – CDC". Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Fredericks, Bob (October 29, 2014). "CDC admits droplets from a sneeze could spread Ebola". New York Post. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ "CDC admits Ebola can be passed to others by sneezing". The Washington Times. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Kuhnhenn, Jim (October 17, 2014). "President Obama appoints Ebola 'czar'". AP News. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "Obama's New Ebola 'Czar' Does Not Have Medical, Health Care Background". CBS DC. October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Davis, Julie Hirschfeld; Shear, Michael D. (October 17, 2014). "Ron Klain, Chief of Staff to 2 Vice Presidents, Is Named Ebola Czar". The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Loney, Jim (October 17, 2014). "Obama appoints Ebola czar; Texas health worker isolated on ship". Reuters. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (October 19, 2014). "First on CNN: Obama will name Ron Klain as Ebola Czar". CNN. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Lavender, Paige (October 17, 2014). "Obama To Appoint Ron Klain As Ebola Czar". The Huffington Post. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Kelley Beaucar Vlahos (October 17, 2014). "White House statement". Fox News. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "Barack Obama 'not at all concerned' about hugging cured Ebola patient – video". The Guardian. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "CDC Details New Ebola Response and Prep Teams". ABC News.

- ^ a b Sabrina Tavernise; Michael D. Shear (October 8, 2014). "U.S. to Begin Ebola Screenings at 5 Airports". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ Zeke J. Miller; Alexandra Sifferlin (October 8, 2014). "U.S. to Screen Passengers From West Africa for Ebola at 5 Airports". Time. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ Karen Matthews (October 11, 2014). "Stepped-up Ebola screening starts at NYC airport". AP.org. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

'Already there are 100 percent of the travelers leaving the three infected countries are being screened on exit. Sometimes multiple times temperatures are checked along that process,' Dr. Martin Cetron, director of the Division of Global Migration and Quarantine for the federal Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, said at a briefing at Kennedy ... The screening will be expanded over the next week to New Jersey's Newark Liberty, Washington Dulles, Chicago O'Hare and Hartsfield-Jackson in Atlanta.

- ^ "DHS imposes new restrictions on travelers from Ebola-stricken countries". Fox News. October 21, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- ^ McNeil, Donald (October 22, 2014). "U.S. Plans 21-Day Watch of Travelers From Ebola-Hit Nations". The New York Times. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "Lawmakers call to halt visas to travelers from Ebola-infected nations". Fox News. October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ Bart Jansen (October 15, 2014). "Republicans call for West Africa travel ban to curb Ebola". usatoday.com. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Malloy signs Ebola emergency declaration". WTNH. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ Anemoma Hartocollis; Emma G. Fitzsimmons (October 25, 2014). "Tested Negative for Ebola, Nurse Criticizes Her Quarantine". The New York Times. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Officials: A Family of six is Quarantined In West Haven After Returning From West Africa. Three other individuals also are being quarantined". Hartford Courant. October 22, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ a b "Travelers in contact with Ebola patients, including returning nurse with fever, now face mandatory 21-day quarantine in New York, New Jersey". NY Daily News. October 24, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ Marchione, Marilynn; Stobbe, Mike (October 24, 2014). "NY, NJ Order Ebola Quarantine for Doctors, Others". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c Matt Flegenheimer, Michael D. Shear, and Michael Barbaro, "Ebola quarantine guidelines for NY and NJ", The New York Times, October 27, 2014.

- ^ Aamer Madhani; David Jackson (October 26, 2014). "White House working on new Ebola guidelines". USA Today. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "Illinois Ebola quarantine". Chicago Tribune. October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ Florida Governor Rick Scott on October 25 authorized mandatory twice daily monitoring for 21 days of people identified as coming from countries affected by Ebola Archived October 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, abc7news.com; accessed October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Illinois clarifies mandatory 21-day Ebola quarantine". Chicago Tribune. October 27, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Weiner, Rachel (October 27, 2014). "Virginia and Maryland increase Ebola monitoring for travelers from West Africa". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ "Protocol outlined for Pennsylvania Ebola monitoring". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. October 24, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Morin, Monte; Adolfo Flores (October 29, 2014). "State orders quarantine for workers who had contact with Ebola". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Bashan, Yoni; West, Melanie Grayce; Haddon, Heather (October 26, 2014). "Nurse Detained in New Jersey for Ebola Calls Conditions 'Really Inhumane'". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ Cohen, Elizabeth; Holland, Leslie; Ellis, Ralph (October 27, 2014). "Nurse describes Ebola quarantine ordeal: 'I was in shock. Now I'm angry'". CNN. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (October 26, 2014). "Nurse Criticizes Quarantine After Negative Ebola Test, Hires Lawyer". NPR. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ "New Jersey Releases Nurse Quarantined for Suspected Ebola". NBC News. October 27, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ "Rutgers University–New Brunswick".

- ^ Shayna Jacobs; Sasha Goldstein; Corky Siemaszko (October 27, 2014). "Nurse Kaci Hickox heading for Maine after leaving New Jersey Ebola quarantine: officials". NY Daily News. New York. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Michelle Kaske (October 29, 2014). "Maine Governor Seeks to Make Nurse Abide by Quarantine". Bloomberg.

- ^ Julia Bayly; Jackie Farwell (October 31, 2014). "After Kaci Hickox wins court reprieve, LePage says he doesn't trust her". Bangor Daily News.

- ^ Ray Sanchez; Catherine E. Shoichet; Faith Karimi (October 31, 2014). "Maine judge rejects quarantine for nurse Kaci Hickox". CNN. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ "Nurse working with Ebola patients lands at ABIA". KVUE. October 29, 2014.

- ^ Luis Martinez (October 27, 2014). "US Army to Quarantine Troops Who Were Fighting Ebola". ABC News. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ "Presidential Memorandum – Authorizing the Exercise of Authority Under Public Law 85-804". November 13, 2014 – via White House Press Office.

- ^ WKYC Staff (October 16, 2014). "Solon closes two schools Thursday as Ebola precaution". wkyc.com. Retrieved October 16, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kara Sutyak (October 16, 2014). "Ebola precautions taken at Cranwood School in Cleveland". fox8. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ "Ohio, Texas schools close amid Ebola scare". USA Today. October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

Three Central Texas schools were closed Thursday over health concerns surrounding two students who traveled on a Monday flight with Vinson.

- ^ "Kids pulled out of class over concerns about principal's trip to Zambia". WAPT.com. October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Mendoza, Dorrine (October 20, 2014). "Ebola hysteria: An epic, epidemic overreaction". CNN.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "Design of a Specialized Airborne-Infection-Isolation Suite" (PDF). HPAC Engineering: 25–33. February 2011. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ "Pre-application Webinar Agenda "Opportunities for Collaborative Research at the NIH Clinical Center" X02 (PAR-13-357) and U01 (PAR-13-358)" (PDF). NIH Office of Extramural Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ ABC News. "US Has Capacity for 11 Ebola Patients at Specialized Hospitals". ABC News.

- ^ Rob Chaney (September 30, 2014). "St. Patrick Hospital 1 of 4 sites in U.S. ready for Ebola patients". Missoulian.com. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "CDC director at today's Biocontainment Unit unveiling". University of Nebraska Medical Center. March 7, 2005.

- ^ Roberts, Dan – News World news Ebola CDC director warns Ebola like 'forest fire' as Congress readies for hearing – Ebola crisis live updates – The Guardian. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ Choi JH, Croyle MA (December 2013). "Emerging targets and novel approaches to Ebola virus prophylaxis and treatment". BioDrugs. 27 (6): 565–83. doi:10.1007/s40259-013-0046-1. PMC 3833964. PMID 23813435.

- ^ Clark DV, Jahrling PB, Lawler JV (September 2012). "Clinical management of filovirus-infected patients". Viruses. 4 (9): 1668–86. doi:10.3390/v4091668. PMC 3499825. PMID 23170178.

- ^ Briggs, Helen (August 7, 2014) "Ebola: Experimental drugs and vaccines", BBC News, Health, Retrieved August 8, 2014

- ^ Rush, James (November 13, 2014). "Ebola virus: Clinical trials of three new treatments for disease to start in West Africa". The Independent. London. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ "What Cured Ebola Patients Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol?", NBC News, August 21, 2014

- ^ Moffett, Matt (August 13, 2014). "Ebola Virus: Infected Priest Has Died in Spain". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ a b "12 Answers To Ebola's Hard Questions", Time, October 23, 2014.

- ^ "Amgen works with Gates Foundation to ramp up Ebola drug ZMapp production", Puget Sound Business Journal, October 20, 2014.

- ^ "Ebola patient Dr. Craig Spencer enters 'next phase' of illness despite treatment with experimental drug Brincidofovir", NY Daily News, October 25, 2014

- ^ "Immune Response Key to Beating Ebola", UConn Today, Univ. of Connecticut, October 30, 2014

- ^ "Ebola survivor Kent Brantly donates blood to help treat NBC cameraman Ashoka Mukpo", The Washington Post, October 8, 2014

- ^ "The decades-old treatment that may save a young Dallas nurse infected with Ebola", The Washington Post, October 14, 2014

- ^ "A Plan to Use Survivors' Blood for Ebola Treatment in Africa", The New York Times, October 3, 2014

- ^ Alison P. Galvani with three others (August 21, 2014). "Ebola Vaccination: If Not Now, When?". Annals of Internal Medicine. 161 (10): 749–50. doi:10.7326/M14-1904. PMC 4316820. PMID 25141813.

- ^ Fausther-Bovendo H, Mulangu S, Sullivan NJ (June 2012). "Ebolavirus vaccines for humans and apes". Curr Opin Virol. 2 (3): 324–29. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2012.04.003. PMC 3397659. PMID 22560007.

- ^ Walsh, Fergus (January 6, 2015). "Ebola: New vaccine trial begins". BBC News. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ "Americans 'can't give in to hysteria or fear' over Ebola: Obama". Reuters. October 18, 2014.

- ^ "WHO: Millions of Ebola Vaccine Doses Ready in 2015", BBC News, October 24, 2014

- ^ Commissioner, Office of the (March 24, 2020). "First FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of Ebola virus disease, marking a critical milestone in public health preparedness and response". FDA. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ McKee, Selina (December 23, 2019). "US approves Merck's Ebola vaccine". PharmaTimes. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ Dan Mangan (October 15, 2014). "Texas College Rejects Nigerian Applicants, Cites Ebola Cases – NBC News". NBCNews.com. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "Navarro College says in a new statement it will postpone recruitment of students from countries at risk for Ebola – Corsicana Daily Sun: Local News". Corsicana Daily Sun. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Bever, Lindsay (October 17, 2014). "Syracuse University disinvites Washington Post photographer because he was in Liberia 3 weeks ago". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ a b Kingkade, Tyloe (October 17, 2014). "Colleges Isolate, Disinvite People Out Of An 'Abundance Of Caution' Over Ebola". Huffington Post. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ Rice, Chelsea. "Ebola Today". Boston.com. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ Besser, Richard E. (October 15, 2014). "Fight fear of ebola with the facts". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ "Harvard update on West Africa Ebola outbreak: October 2014" (PDF). Harvard University: Office of the Provost. October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Spencer S. Hsu; Nia-Malika HendersonSpencer S. Hsu; Nia-Malika Henderson (October 25, 2014). "No mandatory Ebola quarantine for health workers coming to Washington area". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ Jen Christensen. "'Out of control': How the world reacted as Ebola spread". CNN.

- ^ "Time Magazine Honors Ebola Fighters: Samaritan's Purse doctor Kent Brantly is among those honored as Time's Person of the Year". December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ a b "Did Trump Criticize Governors for Backing off Ebola Quarantines in 2014?". Snopes.com. April 22, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- "Report of the Independent Panel On HHS Ebola Response" (PDF). HHS.gov. Health and Human Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 12, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- "Infection Prevention and Control for Ebola in Health Care Settings — West Africa and United States". www.medscape.com. Medscape. Retrieved July 31, 2016.