Influence of the I Ching

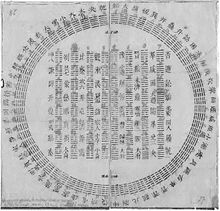

As an important component of Chinese culture, the I Ching, a text over 3,000 years old, is believed to be one of the world's oldest books. The two major branches of Chinese philosophy, Confucianism and Taoism have common roots in the I Ching.[1][2]

Significance for Chinese culture

[edit]From its mythological origins in prehistory (see Fu Xi) and the earliest dates of recorded history in China, the I Ching has been added to by a succession of philosophers, scholars and rulers. Thus, it reflects a thread of thinking and a common cosmology that have been passed through successive generations. In addition to the I Ching's broadly recognized influence on Confucianism and Taoism, it has been shown to have influenced Chinese Buddhism. Fazang, patriarch of the Huayan school, is believed to have drawn on a mode of thought derived from the I Ching.[4]

One of the earliest versions of the I Ching (called, Zhou I, or Changes of Zhou) was the oracle of the Zhou. It played a role in their overthrow of the Shang dynasty by Zhou King Wu in 1070 BCE. An account of Wu's conquest tells of a solar eclipse believed by the King to be an omen from Heaven to march against the Shang. This account has been matched with a solar eclipse that occurred on June 20, 1070 BCE. Thus, the earliest layer of the I Ching has been shown to preserve a hidden history that went undetected for three millennia.[5] The Zhou Yi has been called one of the most important sources of Chinese culture. It has influenced fields as varied as mathematics, science, medicine, martial arts, philosophy, history, literature, art, ethics, military affairs and religion.

Joseph Campbell describes the I Ching as "an encyclopedia of oracles, based on a mythic view of the universe that is fundamental to all Chinese thought."[6]

Confucius

[edit]Confucius was fascinated by the I Ching and kept a copy in the form of "a set of bamboo tablets fastened by a leather thong, [which] was consulted so often that the binding had to be replaced three times. [Confucius] said that if he had fifty years to spare, he would devote them to the I Ching."[7] The ten commentaries of Confucius, (or Ten Wings), transformed the I Ching from a divination text into a "philosophical masterpiece".[8] It has influenced Confucians and other philosophers and scientists ever since.[8]

Influence on Japan

[edit]Prior to the Tokugawa period (1603–1868 CE) in Japan, the Book of Changes was little known and used mostly for divination until Buddhist monks popularized the Chinese classic for its philosophical, cultural and political merits in other literate groups such as the samurai.[9] The Hagakure, a collection of commentaries on the Way of the Warrior, cautions against mistaking it for a work of divination.[10]

Influence on Western culture

[edit]- American historian Michael Nylan, representing UC Berkeley noted the considerable influence of the I Ching on intellectuals in Europe and America. She stated that it is the most familiar of the five Chinese classics, and without doubt, the best-known Chinese book that laid the foundation of modern Western culture beginning the 17th century.[11]

- German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz[11] was keenly interested in the I Ching, and translated I-Ching binary system into modern binary system.[3]

- Author Douglas Adams's The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul features an I Ching pocket calculator that represents anything greater than four as "A Suffusion of Yellow".[12]

- British poet Alan Baker based his prose-poem sequence "The Book of Random Access" (pub. 2011) on the 64 Hexagrams of the I Ching.

- When Danish Physicist Niels Bohr was awarded Denmark's highest honor and the opportunity to create a family coat of arms, he chose the yin-yang symbol, and Latin motto contraria sunt complementa, "opposites are complementary",[13] a nod to his Principle of Complementarity.

- The philosopher and novelist Will Buckingham has used the I Ching extensively, describing it as an 'uncertainty machine'.[14]

- Musician and composer John Cage used the I Ching to decide the arrangements of many of his compositions.

- Composer Andrew Culver and choreographer Merce Cunningham use the I Ching.

- The ABC soap opera Dark Shadows featured yarrow sticks and a copy of the I Ching that allowed characters meditating on the hexagrams to astral travel.

- The hip-hop music group Dead Prez refer to the I Ching in several of their songs and in their logo.

- The D&B-metal music group Marshall Ar.ts use the I Ching hexagram 36 in their logo and refers to it in several songs.

- Author Philip K. Dick used the I Ching when writing The Man in the High Castle and including it in the story as a theme.

- In a 1965 interview, Bob Dylan stated that the book is "the only thing that is amazingly true, period...besides being a great book to believe in, it's also very fantastic poetry" and in a mid-1970s rendition of his song Idiot Wind he sang "I threw the I-Ching yesterday, it said there might be some thunder at the well."[15]

- The film G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra uses a red hexagram tattoo on the right forearm for the Storm Shadow ninja clan.

- The poet Allen Ginsberg wrote a poem called Consulting I Ching Smoking Pot Listening to the Fugs Sing Blake in 1966.[16]

- Musician George Harrison, who composed the Beatles song While My Guitar Gently Weeps, recalls he "picked up a book at random, [the I Ching] opened it, saw "gently weeps", then laid the book down again and started the song".

- Author Hermann Hesse's 1943 novel The Glass Bead Game is mainly concerned with the principles of the I Ching.

- Psychologist Carl Jung wrote a foreword to the Wilhelm–Baynes translation of the I Ching.

- The TV series Lost featured the ba gua as in the logo for The Dharma Initiative.

- Author Terence McKenna's Novelty Theory and Timewave Zero, were inspired by analysis of the King Wen sequence.

- In director Michael Mann's film Collateral, Vincent (Tom Cruise) refers to the I Ching as he tries to teach Max (Jamie Foxx) the importance of improvisation.

- Photek released a song called Book of Changes in 1994.[17]

- The song Chapter 24 from Pink Floyd's first album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, written by Syd Barrett, features lyrics adapted from the I Ching.

- British author Philip Pullman's book The Amber Spyglass features the I Ching amongst the divination methods used by Dr. Mary Malone to communicate with Dust.

- The writer Raymond Queneau had a long-standing fascination with the I Ching.[18]

- I Ching is mentioned in the Monty Python song I Like Chinese, written by Eric Idle.

- In the 1977 novel Monkey Grip by Helen Garner, the protagonist consults the I Ching for its synchronicities relating to a romance with her partner.

- Francophone author Ezechiel Saad and his book Yi King, mythe et histoire delves into the shamanic roots of oracular Chinese thought, and examines the real or legendary bestiary, searching for meaning from psychoanalysis and Western culture.[19]

- Author Neal Stephenson's novel Quicksilver, uses hexagrams for encryption keys that allow Eliza to send messages to "Leibniz" from the court of King Louis XIV.

- In the late 1960s, the comic book Wonder Woman temporarily changed the title character from a superhero to a secret agent, and placed her under the guidance of an elderly mentor known as "I Ching".

- The I Ching is mentioned in Charmed S5E22 'Oh My Goddess (Part 1)'.

- The episode "Grand Deceptions" (episode 4, season 8) of Columbo show the Yi Jing.

References

[edit]- ^ Wilhelm, Richard; Baynes, Cary F.; Carl Jung; Hellmut Wilhelm (1967). The I Ching or Book of Changes. Bollingen Series XIX (3 ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (1st ed. 1950). ISBN 0-691-09750-X. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Wilhelm, Richard; Baynes, Cary F. (5 December 2005). Dan Baruth (ed.). "Introduction to the I Ching". Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ a b Perkins, Franklin. Leibniz and China: A Commerce of Light. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. p 117. Print.

- ^ Lai, Whalen (1980). "The I-ching and the Formation of the Hua-yen Philosophy". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 7 (3). D. Reidel Publishing: 245–258. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6253.1980.tb00239.x. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ Marshall, S.J. (August 2002). The Mandate of Heaven: Hidden History in the I Ching. Columbia University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-231-12299-3. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Campbell, Joseph (12 April 1962). The masks of God: Oriental mythology. Viking Press. p. 411. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Needham, J. (1991). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 2, History of Scientific Thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-521-05800-1.

- ^ a b Abraham, Ralph H. (1999). "Chapter 1. Legendary History of the I Ching". Retrieved 15 February 2008. Internet Archive copy. (See also the whole work by Ralph H. Abraham: Commentaries on the I Ching)

- ^ Wai-ming Ng (2000). The I ching in Tokugawa thought and culture. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-8248-2242-2. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ Yamamoto Tsunetomo; William Scott Wilson (trans.) (21 November 2002). Hagakure: the book of the samurai. Kodansha International. p. 144. ISBN 978-4-7700-2916-4. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ a b Nylan, Michael (2001). The Five "Confucian" Classics. Yale University Press. pp. 204–206. ISBN 978-0-300-08185-5. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Douglas Adams (1991). The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul. Simon and Schuster. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-671-74251-5. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

It was much like an ordinary pocket calculator, except that the LCD screen was a little larger than usual in order to accommodate the abridged judgments of King Wen on each of the sixty-four hexagrams, and also the commentaries of his son, the Duke of Chou, on each of the lines of each hexagram. These were unusual text to see marching across the display of a pocket calculator, particularly as they had been translated from the Chinese via the Japanese and seemed to have enjoyed many adventures on the way.

- ^ I.G. Bearden (17 May 2010). "Bohr family crest". Niels Bohr Institute (University of Copenhagen). Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Buckingham, Will. "The uncertainty machine". Aeon Magazine. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ Cannella, Cara. "Celebrating the Ancient Wisdom of the I-Ching at Beijing's Water Cube". Biographile. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ "Consulting I Ching Smoking Pot Listening To The Fugs Sing Blake (Broadside Poem)". Abebooks. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ "Studio Pressure – Form & Function Vol. 2". Discogs. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ Smith, Richard J. (2012). The "I Ching": A Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-1400841622. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ Saad, Ezechiel (1989). Yi King, mythe et histoire. Paris: Sophora. ISBN 2-907927-00-0.

External links

[edit]- "Between past and present" Shanghai Star 2004-10-09. Accessed: 2006-01-10.

- I Ching Web Edition