Legnica

Legnica | |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

| Coordinates: 51°12′30″N 16°9′37″E / 51.20833°N 16.16028°E | |

| Country | |

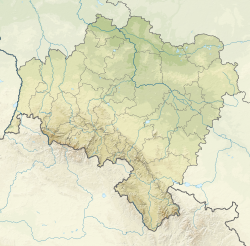

| Voivodeship | |

| County | city county |

| First mentioned | 1004 |

| City rights | 1264 |

| Government | |

| • City mayor | Maciej Kupaj (KO) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 56.29 km2 (21.73 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 113 m (371 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2021) | |

| • Total | 97,300 |

| • Density | 1,765/km2 (4,570/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 59-200 to 59-220 |

| Area code | +48 76 |

| Car plates | DL |

| Highways | |

| National road | |

| Website | www.legnica.um.gov.pl |

Legnica (Polish: [lɛɡˈɲit͡sa] ; German: Liegnitz, pronounced [ˈliːɡnɪts] ; Silesian: Ligńica; Czech: Lehnice; Latin: Lignitium) is a city in southwestern Poland, in the central part of Lower Silesia, on the Kaczawa River and the Czarna Woda. As well as being the seat of the county, since 1992 the city has been the seat of the Diocese of Legnica. As of 2023,[update] Legnica had a population of 97,300 inhabitants.[1]

The city was first referenced in chronicles dating from the year 1004,[2] although previous settlements could be traced back to the 7th century. The name "Legnica" was mentioned in 1149 under High Duke of Poland Bolesław IV the Curly. Legnica was most likely the seat of Bolesław and it became the residence of the dukes of Legnica from 1248 until 1675.[3][4] Legnica is a city over which the Piast dynasty reigned the longest, for about 700 years, from the time of ruler Mieszko I of Poland after the creation of the Polish state in the 10th century, until 1675 and the death of the last Piast duke George William. Legnica is one of the historical burial sites of Polish monarchs and consorts.

Legnica became renowned for the fierce battle that took place at Legnickie Pole near the city on 9 April 1241 during the first Mongol invasion of Poland, which ended in the defeat of the Polish-led Christian coalition by the Mongols.

Legnica is an economic, cultural and academic centre in Lower Silesia, together with Wrocław. The city is renowned for its varied architecture, spanning from early medieval to modern period, and its preserved Old Town with the Piast Castle, one of the largest in Poland.[5] According to the Foreign direct investment ranking (FDI) from 2016, Legnica is one of the most progressive high-income cities in the Silesian region.[6][7]

Population[edit]

As of 31 December 2012[update] Legnica has 102,708 inhabitants and is the third largest city in the voivodeship (after Wrocław and Wałbrzych) and 38th in Poland. It also constitutes the southernmost and the largest urban center of a copper deposit (Legnicko-Głogowski Okręg Miedziowy) with agglomeration of 448,617 inhabitants. Legnica is the largest city of the conurbation and is a member of the Association of Polish Cities.

History[edit]

Pre-history[edit]

Archaeological research conducted in eastern Legnica in the late 1970s, showed the existence of a bronze foundry and the graves of three metallurgists. The find indicates a time interval about year 1000 BC.[8]

A settlement of the Lusatian culture people existed in the 8th century B.C. After invasions of Celts beyond upper Danube basin, the area of Legnica and north foothills of Sudetes was infiltrated by Celtic settlers and traders.

Tacitus and Ptolemy recorded the ancient nation of Lugii (Lygii) in the area, and mentioned their town of Lugidunum, which has been attributed to both Legnica[9] and Głogów.[10]

Early Poland[edit]

Slavic Lechitic tribes moved into the area in the 8th century.

The city was first officially mentioned in chronicles from 1004,[11] although settlement dates to the 7th century. Dendrochronological research proves that during the reign of Mieszko I of Poland, a new fortified settlement was built here in a style typical of the early Piast dynasty.[12] It is mentioned in 1149 when High Duke Bolesław IV the Curly funded a chapel at the St. Benedict monastery.[13] Legnica was the most likely place of residence for Bolesław[14] and it became the residence of the high dukes of Poland in 1163[2] and was the seat of a principality ruled from 1248 until 1675.

Legnica became famous for the battle that took place at Legnickie Pole near the city on 9 April 1241 during the First Mongol invasion of Poland. The Christian army of the Polish duke Henry II the Pious of Silesia, supported by feudal nobility, which included in addition to Poles, Bavarian miners and military orders and Czech troops, was decisively defeated by the Mongols. The Mongols killed Henry and destroyed his forces, then turned south to rejoin the rest of the Mongol armies, which were massing at the Plain of Mohi in Hungary via Moravia against a coalition of King Bela IV and his armies, and Bela's Kipchak allies.[15]

After the war, nonetheless, the city was developing rapidly. In 1258 at the church of St. Peter, a parish school was established, probably the first of its kind in Poland.[16] Around 1278 a Dominican monastery was founded by Bolesław II the Horned,[16] who was buried there as the only monarch of Poland to be buried in Legnica. Already by 1300 there was a city council in Legnica.[16] Duke Bolesław III the Generous granted new trade privileges in 1314 and 1318 and allowed the construction of a town hall, and in 1337 the first waterworks were built.[16] In the years 1327–1380 a new Gothic church of Saint Peter (today's Cathedral) was erected in place of the old one,[16] and is one of Legnica's landmarks since. Also by the 14th century the city walls were erected.[16] In 1345 the first coins were produced in the local mint.[16] In 1374, the potters' guild was founded, as one of the oldest in Silesia.[16] Queen consort of Poland Hedwig of Sagan died in Legnica in 1390 and was buried in the local collegiate church, which has not survived to this day.[17]

Duchy of Legnica[edit]

As the capital of the Duchy of Legnica at the beginning of the 14th century, Legnica was one of the most important cities of Central Europe, having a population of nearly 16,000 residents. The city began to expand quickly after the discovery of gold in the Kaczawa River between Legnica and Złotoryja (Goldberg). Unfortunately, such a growth rate can not be maintained long. Shortly after the city reached its maximum population increase, wooden buildings which had been erected during this period of rapid growth were devastated by a huge fire. The fire decreased the number of inhabitants in the city and halted any significant further development for many decades.

Legnica, along with other Silesian duchies, became a vassal of the Kingdom of Bohemia during the 14th century and was included within the multi-ethnic Holy Roman Empire, however remained ruled by local dukes of the Polish Piast dynasty. In 1454, a local rebellion prevented Legnica from falling under direct rule of the Bohemian kings.[18] In 1505, Duke Frederick II of Legnica met in Legnica with the duke of nearby Głogów, Sigismund I the Old, the future king of Poland.[16]

The Protestant Reformation was introduced in the duchy as early as 1522 and the population became Lutheran. In 1526, a Protestant university was established in Legnica, which, however, was closed in 1529.[16] In 1528 the first printing house in Legnica was established.[16] After the death of King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia at Mohács in 1526, Legnica became a fief of the Habsburg monarchy of Austria. The first map of Silesia was made by native son Martin Helwig. The city suffered during the Thirty Years' War. In 1633 a plague epidemic broke out, and in 1634 the Austrian army destroyed the suburbs.[16]

In 1668 Duke of Legnica Christian presented his candidacy to the Polish throne, however, in the 1669 Polish–Lithuanian royal election he wasn't chosen as King. In 1676, Legnica passed to direct Habsburg rule after the death of the last Silesian Piast duke and the last Piast duke overall, George William (son of Duke Christian), despite the earlier inheritance pact by Brandenburg and Silesia, by which it was to go to Brandenburg. The last Piast duke was buried in the St. John's church in Legnica in 1676.[16]

18th and 19th centuries[edit]

Silesian aristocracy was trained at the Liegnitz Ritter-Akademie, established in the early 18th century. One of two main routes connecting Warsaw and Dresden ran through the city in the 18th century and Kings Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III of Poland traveled that route many times.[19] The postal milestone of King Augustus II comes from that period.[20]

In 1742 most of Silesia, including Liegnitz, became part of the Kingdom of Prussia after King Frederick the Great's defeat of Austria in the War of the Austrian Succession. In 1760 during the Seven Years' War, Liegnitz was the site of the Battle of Liegnitz when Frederick's army defeated an Austrian army led by Laudon.

During the Napoleonic Wars and Polish national liberation fights, in 1807 Polish uhlans were stationed in the city,[21] and in 1813, the Prussians, under Field Marshal Blücher, defeated the French forces of MacDonald in the Battle of Katzbach (Kaczawa) nearby. After the administrative reorganization of the Prussian state following the Congress of Vienna, Liegnitz and the surrounding territory (Landkreis Liegnitz) were incorporated into the Regierungsbezirk (administrative district) of Liegnitz, within the Province of Silesia on 1 May 1816. Along with the rest of Prussia, the town became part of the German Empire in 1871 during the unification of Germany. On 1 January 1874 Liegnitz became the third city in Lower Silesia (after Breslau and Görlitz) to be raised to an urban district, although the district administrator of the surrounding Landkreis of Liegnitz continued to have his seat in the city. Its military garrison was home to Königsgrenadier-Regiment Nr. 7 a military unit formed almost exclusively out of Polish soldiers.[22]

The 20th century[edit]

The census of 1910 gave Liegnitz's population as 95.86% German, 0.15% German and Polish, 1.27% Polish, 2.26% Wendish, and 0.19% Czech. On 1 April 1937 parts of the Landkreis of Liegnitz communities of Alt Beckern (Piekary), Groß Beckern (Piekary Wielkie), Hummel, Liegnitzer Vorwerke, Pfaffendorf (Piątnica) und Prinkendorf (Przybków) were incorporated into the city limits. After the Treaty of Versailles following World War I, Liegnitz was part of the newly created Province of Lower Silesia from 1919 to 1938, then of the Province of Silesia from 1938 to 1941, and again of the Province of Lower Silesia from 1941 to 1945. After the Nazi Party came to power in Germany, as early as 1933, a boycott of local Jewish premises was ordered, during the Kristallnacht in 1938 the synagogue was burned down,[23] and in 1939 the local Polish population was terrorized and persecuted.[24] A Nazi court prison was operated in the city with a forced labour subcamp.[25] During World War II, several members of the Polish resistance movement were imprisoned and sentenced to death there.[26] The Germans also established two forced labour camps in the city, as well as two prisoner of war labor subcamps of the POW camp located in Żagań (then Sagan), and one labor subcamp of the Stalag VIII-A POW camp in Zgorzelec (then Görlitz).[27]

After the defeat of Nazi Germany during World War II, Liegnitz and all of Silesia east of the Neisse was preliminarily transferred to Poland following the Potsdam Conference in 1945. The majority of the German population was either expelled in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement or fled from the city.

The city was repopulated with Poles, including expellees from pre-war eastern Poland after its annexation by the Soviet Union. Also Greeks, refugees of the Greek Civil War, settled in Legnica in 1950.[28] As the medieval Polish name Lignica was considered archaic, the town was renamed Legnica. The transfer to Poland decided at Potsdam in 1945 was officially recognized by East Germany in 1950, by West Germany under Chancellor Willy Brandt in the 1970 Treaty of Warsaw, and finally by the reunited Germany by the Two Plus Four Agreement in 1990. By 1990 only a handful of Polonized Germans, prewar citizens of Liegnitz, remained of the pre-1945 German population. In 2010 the city celebrated the 65th anniversary of the return of Legnica to Poland and its liberation from Nazi Germany.[29]

The city was only partly damaged in World War II. In June 1945 Legnica was briefly the capital of the Lower Silesian (Wrocław) Voivodship, after the administration was moved there from Trzebnica and before it was finally moved to Wrocław.[30] In 1947, the Municipal Library was opened, in 1948 a piano factory was founded, and in the years 1951-1959 Poland's first copper smelter was built in Legnica.[30] After 1965 most parts of the preserved old town with its town houses were demolished, the historical layout was abolished, and the city was rebuilt in modern form.[31]

From 1945 to 1990, during the Cold War, the headquarters of the Soviet forces in Poland, the so-called Northern Group of Forces, was located in the city. This fact had a strong influence on the life of the city. For much of the period, the city was divided into Polish and Soviet areas, with the latter closed to the public. These were first established in July 1945, when the Soviets forcibly ejected newly arrived Polish inhabitants from the parts of the city they wanted for their own use. The ejection was perceived by some as a particularly brutal action, and rumours circulated exaggerating its severity, though no evidence of anyone being killed in the course of it has come to light. In April 1946 city officials estimated that there were 16,700 Poles, 12,800 Germans, and 60,000 Soviets in Legnica.[32] In October 1956, the largest anti-Soviet demonstrations in Lower Silesia took place in Legnica.[30] The last Soviet units left the city in 1993.

Between 1 June 1975 and 31 December 1998 Legnica was the capital of the Legnica Voivodeship. In 1992 the Roman Catholic Diocese of Legnica was established, Tadeusz Rybak became the first bishop of Legnica.[33] New local newspapers and a radio station were founded in the 1990s.[33] In 1997, Legnica was visited by Pope John Paul II.[33] The city suffered in the 1997 Central European flood.[33]

Climate[edit]

Legnica has an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb).[34][35]

| Climate data for Legnica (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.8 (76.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.4 (88.5) |

36.9 (98.4) |

37.3 (99.1) |

38.4 (101.1) |

35.1 (95.2) |

29.3 (84.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

38.4 (101.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.1 (37.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.2 (32.4) |

1.2 (34.2) |

4.4 (39.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

1.4 (34.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

0.5 (32.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

5.1 (41.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.8 (−18.0) |

−29.7 (−21.5) |

−21.4 (−6.5) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

0.5 (32.9) |

3.4 (38.1) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−16.8 (1.8) |

−24.7 (−12.5) |

−29.7 (−21.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 25.0 (0.98) |

22.3 (0.88) |

33.3 (1.31) |

25.9 (1.02) |

57.8 (2.28) |

65.9 (2.59) |

89.6 (3.53) |

64.4 (2.54) |

48.4 (1.91) |

35.7 (1.41) |

28.9 (1.14) |

24.5 (0.96) |

521.6 (20.54) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 4.4 (1.7) |

4.3 (1.7) |

3.2 (1.3) |

0.4 (0.2) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (0.2) |

1.8 (0.7) |

3.1 (1.2) |

4.4 (1.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 15.47 | 13.10 | 14.03 | 10.80 | 13.00 | 13.90 | 13.50 | 11.97 | 11.37 | 12.97 | 13.70 | 14.63 | 158.43 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0 cm) | 11.6 | 9.2 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 6.6 | 35.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83.6 | 80.6 | 76.9 | 70.5 | 72.3 | 72.6 | 70.4 | 70.5 | 77.2 | 81.5 | 86.1 | 84.9 | 77.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 58.2 | 81.7 | 126.0 | 196.7 | 238.3 | 237.6 | 249.2 | 242.6 | 162.5 | 119.1 | 66.3 | 53.3 | 1,831.4 |

| Source 1: Institute of Meteorology and Water Management[36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteomodel.pl (records, relative humidity 1991–2020)[44][45][46] | |||||||||||||

Sights[edit]

Legnica is a city with rich historical architecture, ranging from Romanesque and Gothic through the Renaissance and Baroque to Historicist styles. Among the landmarks of Legnica are:

- the Piast Castle, former seat of the local dukes of the Piast dynasty

- Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul

- Market Square (Rynek) with:

- Baroque Old Town Hall (Stary Ratusz)

- Helena Modrzejewska Theatre

- Kamienice Śledziowe ("Herring Houses")

- Dom Pod Przepiórczym Koszem ("Under the Quail Basket House")

- former Dominican and later Benedictine monastery, founded by Bolesław II the Horned, who was buried there as the only monarch of Poland to be buried in Legnica; nowadays housing the I Liceum Ogólnokształcące im. Tadeusza Kościuszki (high school)

- Saint John the Baptist Church with a mausoleum of the last Piast dukes

- New Town Hall (Nowy Ratusz), seat of city authorities

- Saint Mary church

- Copper Museum (Muzeum Miedzi)

- Medieval Chojnów and Głogów Gates, remnants of the medieval city walls

- Former Knight Academy, now housing municipal offices and a branch of the Copper Museum

- Public Library and archive

- Park Miejski ("City Park"), the oldest and largest park of Legnica

There is also a monument of Pope John Paul II and a postal milestone of King Augustus II the Strong from 1725 in Legnica.[20]

-

Piast Castle courtyard

-

Kamienice Śledziowe at the Market Square

-

Helena Modrzejewska Theatre

-

Saint Mary church

-

Copper Museum

-

Under the Quail Basket House

Economy[edit]

In the 1950s and 1960s, the local copper and nickel industries became a major factor in the economic development of the area. Legnica houses industrial plants belonging to KGHM Polska Miedź, one of the largest producers of copper and silver in the world. The company owns a large copper mill on the western outskirts of town. Legnica Special Economic Zone was established in 1997.[47]

Education[edit]

Legnica is a regional academic center with seven universities enrolling approximately 16,000 students.

- State-run colleges and universities

- Witelon University of Applied Sciences (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa im. Witelona) [1]

- Wrocław University of Technology [2]

- Foreign Language Teacher Training College in Legnica [3]

- Other

- Wyższa Szkoła Zarządzania / The Polish Open University [4]

- Legnica University of Management [5]

- Wyższe Seminarium Duchowne / Seminary [6]

Environment[edit]

Legnica is noted for its parks and gardens, and has seven hundred hectares of green space, mostly along the banks of the Kaczawa; the Tarninow district is particularly attractive.[48]

Roads[edit]

To the south of Legnica is the A4 motorway. Legnica has also a district, which is a part of national road no 3. The express road S3 building has been planned nearby.

Public transport[edit]

In the city there are 20 regular bus lines, 1 belt-line, 2 night lines and 3 suburban.

The town has an airport (airport code EPLE) with a 1600-metre runway, the remains of a former Soviet air base, but it is (as of 2007[update]) in a poor state and not used for commercial flights.

Sports[edit]

- Miedź Legnica – men's football team (Polish Cup winner 1992; played in the Ekstraklasa in season 2018–19)

Films produced in Legnica[edit]

In recent years Legnica has been frequently used as a film set for the following films as a result of its well preserved Old Town, proximity to Germany and low costs:

- Przebacz (dir. M. Stacharski) – 2005

- A Woman in Berlin (dir. M. Färberböck) – 2007

- Wilki (dir. F. Fromm) – 2007

- Little Moscow (dir. W. Krzystek) – 2008

- The Author of Himself: The Life of Marcel Reich-Ranicki (dir. D. Zahavi) – 2008

- Die Wölfe (dir. F. Fromm) – 2009

- Jack Strong (dir. W. Pasikowski) – 2014

Politics[edit]

Municipal politics[edit]

Legnica tends to be a left-of-center town with a considerable influence of workers' unions. The Municipal Council of Legnica (Rada miejska miasta Legnica) is the legislative branch of the local government and is composed of 25 members elected in local elections every five years. The mayor or town president (Prezydent miasta) is the executive branch of the local government and is directly elected in the same municipal elections.

Legnica – Jelenia Góra constituency[edit]

Members of Parliament (Sejm) elected from Legnica-Jelenia Gora constituency:

- Ryszard Bonda, Samoobrona

- Bronisława Kowalska, SLD-UP

- Adam Lipiński, PiS

- Tadeusz Maćkała, PO

- Ryszard Maraszek, SLD-UP

- Olgierd Poniźnik, SLD-UP

- Władysław Rak, SLD-UP

- Tadeusz Samborski, PSL

- Jerzy Szmajdziński, SLD-UP

- Halina Szustak, LPR

- Michał Turkiewicz, SLD-UP

- Ryszard Zbrzyzny, SLD-UP

Notable people[edit]

- Henry II the Pious (1196/1207–1241), High Duke of Poland

- Witelo (1230–died 1280–1314), philosopher and scientist

- Bolesław II the Bald (1220–1278), High Duke of Poland

- Hans Aßmann Freiherr von Abschatz (1646–1699), lyricist and translator

- Georg Rudolf Böhmer (1723–1803), physician and botanist

- Johann Wilhelm Ritter (1776–1810), scientist, philosopher, discoverer of ultraviolet radiation

- Heinrich Wilhelm Dove (1803–1879) physicist

- Benjamin Bilse (1816–1902), conductor and composer

- Karl von Vogelsang (1818–1890), Catholic journalist, politician and social reformer

- Leopold Kronecker (1823–1891), mathematician

- Hugo Rühle (1824–1888), physician

- Gustav Winkler (1867–1954), textile manufacturer

- Wilhelm Schubart (1873–1960) classical philologist, historian and papyrologist

- Paul Löbe (1875–1967), social democratic politician

- Erich von Manstein (1887–1973) field marshal

- Gert Jeschonnek (1912–1999), an officer of the Navy, Vice Admiral, Chief of Navy

- Hans-Heinrich Jescheck (1915–2009), jurist

- Günter Reich (1921–1989), opera singer (baritone)

- Claus-Wilhelm Canaris (1937–2021), jurist and legal philosopher

- Uta Zapf (born 1941), politician (SPD), member of the Bundestag from 1990 to 2013

- Anna Dymna (born 1951), TV, film and theatre actress

- Jacek Oleksyn (born 1953), biologist

- Włodzimierz Juszczak (born 1957), bishop of the Eparchy of Wroclaw–Gdansk of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

- Marzena Kipiel-Sztuka (born 1965), actress

- Beata Tadla (born 1975), journalist and TV presenter

- Tomasz Kot (born 1977), actor

- Marek Pająk (born 1977), musician

- Popek (born 1978), rapper and MMA fighter

- Mariusz Lewandowski (born 1979), footballer player

- Aleksandra Klejnowska (born 1982), weightlifter

- Marcin Robak (born 1982), football player

- Jagoda Szmytka (born 1982), composer

- Jakub Popiwczak (born 1996), volleyball player

- Joanna Jarmołowicz (born 1994), actress

- Łukasz Poręba (born 2000), football player

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

In fiction[edit]

Legnica and its then ruler Count Conrad figure prominently in the alternate history series The Crosstime Engineer, set in the period of 1230 to 1270, by Leo Frankowski.[citation needed]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Local Data Bank". Statistics Poland. Retrieved 9 August 2022. Data for territorial unit 0262000.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 594.

- ^ Smahel, Frantisek (2022). Festivities, Ceremonies, and Rituals in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown in the Late Middle Ages. Martin Nodl, Václav Žůrek. Boston: BRILL. pp. 179, 199. ISBN 978-90-04-51401-0. OCLC 1336402730.

- ^ Thum, Gregor (2011). Uprooted : how Breslau became Wrocław during the century of expulsions. Princeton. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-4008-3996-4. OCLC 744588454.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "*** LEGNICA *** ZAMEK W LEGNICY *** LEGNICA ***". Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ https://www.um.olawa.pl/attachments/article/601/Polish%20Cities%20of%20the%20Future%202015_16.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Dolny Śląsk najbogatszy w Polsce, a Wrocław zaraz za Warszawą (RANKING NAJBOGATSZYCH) - Gazetawroclawska.pl". Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Brzytwy sprzed 3 tysięcy lat w grobach kowali". 26 December 2016.

- ^ Pierre Deschamps. Dictionnaire de géographie ancienne et moderne. Straubling & Müller, 1922.

- ^ James Cowles Prichard. Researches into the Physical History of Mankind. Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper. London, 1841.

- ^ "Legnica".

- ^ Korta, Wacław (2013). Historia Śląska do 1763 roku (in Polish). Warsaw: DiG. p. 63.

- ^ Łaborewicz, Edyta (1997). "ŹRÓDŁA DO DZIEJÓW KOŚCIOŁA W LEGNICY" (PDF). Archeion (in Polish). 97: 149–153. ISSN 0066-6041.

- ^ Bar, Joachim Roman (1986). "Polscy święci". Akademia Teologii Katolickiej. 9–10: 36.

- ^ SINOR, DENIS (1999). "The Mongols in the West". Journal of Asian History. 33 (1): 1–44. ISSN 0021-910X. JSTOR 41933117.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Od miasta lokacyjnego do końca czasów piastowskich". Legnica.eu (in Polish). Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "Królowa z drugiej ligi". Legnica.Gosc.pl (in Polish). 18 January 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ T. Gumiński, E. Wiśniewski, Legnica. Przewodnik po mieście, Legnica 2001, p. 15.

- ^ "Informacja historyczna". Dresden-Warszawa (in Polish). Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Legnica - Słup milowy". PolskaNiezwykla.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ "Legnica - Tablica pamiątkowa poświęcona ułanom Legii Nadwiślańskiej". PolskaNiezwykla.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ Sedan 1870. Ryszard Dzieszyńsk, page 52, Bellona 2009

- ^ "Okres rządów hitlerowskich". Legnica.eu (in Polish). Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Cygański, Mirosław (1984). "Hitlerowskie prześladowania przywódców i aktywu Związków Polaków w Niemczech w latach 1939 - 1945". Przegląd Zachodni (in Polish) (4): 35–36.

- ^ "Gerichtsgefängnis Lignitz". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Encyklopedia konspiracji Wielkopolskiej 1939–1945 (in Polish). Poznań: Instytut Zachodni. 1998. pp. 99, 114, 183, 304, 321, 434, 529. ISBN 83-85003-97-5.

- ^ Lusek, Joanna; Goetze, Albrecht (2011). "Stalag VIII A Görlitz. Historia – teraźniejszość – przyszłość". Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny (in Polish). 34. Opole: 44.

- ^ Kubasiewicz, Izabela (2013). "Emigranci z Grecji w Polsce Ludowej. Wybrane aspekty z życia mniejszości". In Dworaczek, Kamil; Kamiński, Łukasz (eds.). Letnia Szkoła Historii Najnowszej 2012. Referaty (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 117.

- ^ Wala, Grzegorz (9 February 2010). "65. rocznica wyzwolenia Legnicy - foto relacja". Legniczanin.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "[PRL]" (in Polish). Legnica.eu. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Dehio - Handbuch der Kunstdenkmäler in Polen: Schlesien, Herder-Institut Marburg and Krajowy Osrodek Badan i Dokumentacji Zabytkow Warszawa, Deutscher Kunstverlag 2005, ISBN 3-422-03109-X, page 521

- ^ "ARMIA CZERWONA NA DOLNYM ŚLĄSKU" (in Polish). Institute of National Remembrance. Archived from the original on 21 March 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Okres III Rzeczpospolitej". Legnica.eu (in Polish). Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Kottek, Markus; Grieser, Jürgen; Beck, Christoph; Rudolf, Bruno; Rubel, Franz (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorologische Zeitschrift. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L. & McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- ^ "Średnia dobowa temperatura powietrza". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Średnia minimalna temperatura powietrza". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Średnia maksymalna temperatura powietrza". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Miesięczna suma opadu". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Liczba dni z opadem >= 0,1 mm". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Średnia grubość pokrywy śnieżnej". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Liczba dni z pokrywą śnieżna > 0 cm". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Średnia suma usłonecznienia (h)". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Legnica Absolutna temperatura maksymalna" (in Polish). Meteomodel.pl. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Legnica Absolutna temperatura minimalna" (in Polish). Meteomodel.pl. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Legnica Średnia wilgotność" (in Polish). Meteomodel.pl. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Legnica Special Economic Zone". Polish Investment and Trade Agency. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Legnica: Welcome to Legnica Archived 9 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Miasta Partnerskie". portal.legnica.eu (in Polish). Legnica. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

External links[edit]

- Jewish Community in Legnica on Virtual Shtetl0

- Legnica - Liegnitz, Lignica na portalu polska-org.pl (in Polish)

- Municipal website (in Polish)

- Lca.pl (in Polish)

- City hall (in Polish)

- Legnica (in Polish)