First Horizon Park

| |

First Horizon Park at dusk | |

| |

| Former names | First Tennessee Park (2015–2019) |

|---|---|

| Location | 19 Junior Gilliam Way[1] Nashville, Tennessee United States |

| Coordinates | 36°10′22″N 86°47′05″W / 36.17278°N 86.78472°W |

| Elevation | 405 ft (123 m) |

| Owner | Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County |

| Operator | Nashville Sounds Baseball Club |

| Capacity | 8,500 (fixed seating)[7] 10,000 (plus berm seating)[7] |

| Record attendance | 12,409 (July 16, 2022; Nashville Sounds vs. Memphis Redbirds)[8] |

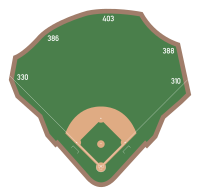

| Field size | Baseball: Left field: 330 ft (100 m) Left-center field: 386 ft (118 m) Center field: 403 ft (123 m) Right-center field: 388 ft (118 m) Right field: 310 ft (94 m)[4]  Soccer: 115 yd × 72 yd (105 m × 66 m)[9] |

| Acreage | 10.8 acres (4.4 ha)[4] |

| Surface | Latitude 36 Bermudagrass[4] |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | January 27, 2014[2] |

| Opened | April 17, 2015[3] |

| Construction cost | $91 million[5] ($117 million in 2023 dollars[6]) |

| Architect | Populous[7] Hastings Architecture Associates[7] |

| Project manager | Gobbell Hays Partners[7] Capital Project Solutions[7] |

| Structural engineer | Walter P. Moore[7] |

| Services engineer | Smith Seckman Reid[7] |

| General contractor | Barton Malow/Bell/Harmony, A Joint Venture[7] |

| Tenants | |

| Nashville Sounds (PCL/AAAE/IL) 2015–present Nashville SC (USLC) 2018–2019 | |

First Horizon Park, formerly known as First Tennessee Park, is a baseball park in downtown Nashville, Tennessee, United States. The home of the Triple-A Nashville Sounds of the International League, it opened on April 17, 2015, and can seat up to 10,000 people. It replaced the Sounds' former home, Herschel Greer Stadium, where the team played from its founding in 1978 through 2014.

The park was built on the site of the former Sulphur Dell, a minor league ballpark in use from 1885 to 1963. It is located between Third and Fifth Avenues on the east and west (home plate, the pitcher's mound, and second base are directly in line with Fourth Avenue to the stadium's north and south) and between Junior Gilliam Way and Harrison Street on the north and south. The Nashville skyline can be seen from the stadium to the south.

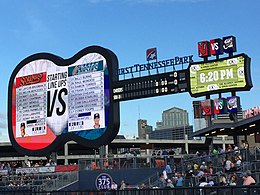

The design of the park incorporates elements of Nashville's baseball and musical heritage and the use of imagery inspired by Sulphur Dell, the city's former baseball players and teams, and country music. Its most distinctive feature is its guitar-shaped scoreboard—a successor to the original guitar scoreboard at Greer Stadium. The ballpark's wide concourse wraps entirely around the stadium and provides views of the field from every location.

Though primarily a venue for the Nashville Sounds, collegiate and high school baseball teams based in the area, such as the Vanderbilt Commodores and Belmont Bruins, have played some games at the ballpark. Nashville SC, a soccer team of the United Soccer League Championship, played its home matches at the facility from 2018 to 2019. It has also hosted other events, including celebrity softball games and various food and drink festivals.

History

[edit]Planning

[edit]As early as 2006, the Nashville Sounds had planned to leave Herschel Greer Stadium for a new ballpark to be called First Tennessee Field located on the west bank of the Cumberland River.[10] The US$43 million facility would have been the central part of a retail, entertainment, and residential complex which was expected to continue the revitalization of Nashville's "SoBro" (South of Broadway) district,[11] but the project was abandoned in April 2007 after the city, developers, and team could not come to terms on a plan to finance its construction.[12] Instead, Greer was repaired and upgraded to keep it close to Triple-A standards until a new stadium could be built.[13] In late 2013, talks about the construction of a new ballpark were revived.[14] Three possible sites were identified by the architectural firm Populous as being suitable for a new stadium: Sulphur Dell, the North Gulch area, and the east bank of the Cumberland River across from the site proposed for the First Tennessee Field project.[11][15] The chosen location was the site of Sulphur Dell on which baseball had been played as early as 1870.[14] Known in its early days as Sulphur Spring Park and Athletic Park, the first grandstand was erected in 1885 for the Nashville Americans, the city's first professional baseball team.[14] Sulphur Dell remained Nashville's primary ballpark until its abandonment in 1963 and demolition in 1969.[14]

Mayor Karl Dean drafted plans for financing the stadium and acquiring the necessary land from the state.[14] The deal involved the Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County (Metro) receiving the state-owned Sulphur Dell property—then in use as a parking lot for state employees—in exchange for paying the state $18 million for the construction of a 1,000-car parking garage on the site and $5 million for an underground parking garage below the proposed new state library and archives.[16] The city also acquired the land on which the Nashville School of the Arts is located.[16]

The financing plan involved public and private funding. At the time, the city planned to pay $75 million for the acquisition of the land and construction of the stadium project.[17][18] However, a 2017 audit revealed that it had actually paid $91 million after accounting for additional costs associated with the expedited schedule and infrastructure work around the project site.[5] The stadium is owned by the city and is leased to the team for 30 years, until 2045.[16] The Sounds ownership group agreed to spend $50 million on a new, mixed-use and retail development located on a plot abutting the ballpark to the east by the third base/left field concourse.[16] This land was sold to Chris and Tim Ward, sons of co-owner Frank Ward, who built a two-story retail center on the site.[19] This building is anchored by a Brooklyn Bowl, featuring a bowling alley, live music space, and a restaurant and bar, that opened in June 2020.[20][21] Adjacent to this and overlooking the third base concourse just outside the stadium by the left field entrance is a two-story bar called Third and Home, which also opened in June 2020.[22] As of February 2022, developer Portman Residential is building a seven-story, 356-unit residential structure with retail and restaurant space beyond the left-center field wall along Third and Fourth avenues to be known as Ballpark Village, which is expected to be completed in early 2024.[23] North of the site, Embrey Development built a privately funded 306-unit luxury apartment complex called The Carillon.[24] The city's original $75 million planned expenditure resulted in taking on $4.3 million in annual debt, paid for by five city revenue streams: an annual $700,000 Sounds' lease payment, $650,000 in stadium-generated sales tax revenue, $750,000 in property taxes from the Ward and Portman developments, $675,000 in property taxes from the Embrey development, and $520,000 in tax increment financing.[16] The additional overage was paid with existing Metro capital funds.[5] The city pays $345,000 for annual maintenance of the stadium.[16]

Construction

[edit]The ballpark project received the last of its necessary approbations from the Metro Council, the State Building Commission, and the Nashville Sports Authority on December 10, 2013.[25][26] Groundbreaking took place on January 27, 2014; the public ceremony was attended by Mayor Dean, Sounds owner Frank Ward, Minor League Baseball president Pat O'Conner, and Milwaukee Brewers General Manager Doug Melvin.[2] At the time, the Sounds were the Triple-A affiliate of the Brewers.[27]

The construction team began site excavation on March 3, 2014.[26] Workers unearthed artifacts dating to around 1150 AD. Fire pits and broken pieces of ceramic pans were found in the ground below what would be left field. Archaeologists believe the area was the site of a Native American settlement and that the artifacts were the remnants of a workshop where mineral water from underground sulfur-bearing springs was boiled to collect salt.[28] The artifacts are on permanent display in the Tennessee State Museum's Mississippian Period exhibit.[29] A portion of the property was used as a city cemetery in the 1800s. The interred were relocated.[30] In 1885, during the construction of Sulphur Spring Park, workers unearthed bowls, shells, a flint chisel, and human skeletons believed to belong to Mound Builders.[31]

Construction of the ballpark's steel frame began on August 18;[26] 2,435 short tons (2,209 metric tons) of steel and 16,314 cu yd (12,473 m3) of concrete were used.[26] By November 3, the installation and testing of the stadium's four free-standing light poles and two concourse-based lighting arrays had begun.[26] Installation of the 8,500 seats started on January 20, 2015.[26] The guitar-shaped scoreboard began to be installed on February 23.[26] On March 19, the home plate was transferred from Greer Stadium and crews began laying the sod.[26]

During construction, the need for new water and electrical supply lines arose. Because these were not factored into the original $65-million cost, another $5 million was appropriated from existing capital funds.[32] An additional $5 million was later required to pay for cleaning contaminated soil, increased sub-contractor pricing, additional labor costs incurred by delays caused by snow and ice, and upgrades including the guitar-shaped scoreboard.[17] The Sounds ownership team contributed $2 million toward the cost of the scoreboard.[17] These and other additional expenditures, such as a $9.5-million greenway, $5.6 million for street paving, sidewalks, and electrical work, and $3.6 million in flood prevention, brought the total construction cost of the stadium to $56 million and the total cost of the project to $91 million.[5]

The facility received LEED silver certification by the U.S. Green Building Council in April 2015 for its level of environmental sustainability and for using strategies for responsible site development, water savings, energy efficiency, materials selection, and indoor environmental quality.[33][34] Some of the ballpark's environmentally friendly initiatives include a 2,800 sq ft (260 m2) green roof on a concessions building along right field, rainwater harvesting, and a rain garden.[3] A section of greenway beyond the outfield wall connects the Cumberland River Greenway to the Bicentennial Mall Greenway.[35] The project team also diverted or recycled 90 percent of construction waste from landfills, and almost a third of building materials were regionally sourced.[34]

Naming rights

[edit]Memphis-based bank First Tennessee purchased the naming rights to the stadium in April 2014 for ten years with an option for a further ten years, naming it First Tennessee Park.[36] The bank's name had been attached to the team's previous attempt at building a new stadium a decade earlier.[10] Financial terms of the deal were not disclosed. First Horizon National Corporation, the parent company of First Tennessee, began unifying its companies under the First Horizon name in late 2019. Subsequently, the ballpark was renamed First Horizon Park in January 2020.[37][38]

Tenants and events

[edit]Minor League Baseball

[edit]

In the ballpark's inaugural game on April 17, 2015, the Nashville Sounds defeated the Colorado Springs Sky Sox, 3–2 in 10 innings, courtesy of a walk-off double hit by Max Muncy that scored Billy Burns from first base.[39] Nashville pitcher Arnold León recorded the park's first strikeout when Colorado Springs' Matt Long struck out swinging as the leadoff hitter at the top of the first inning.[39] The park's first hit was a left-field single that came in the top of the second inning off the bat of the Sky Sox's Matt Clark.[39] Clark also recorded the stadium's first RBI, slapping a single to center field in the fourth inning that sent Luis Sardiñas across the plate for the ballpark's first run.[40] The first home run in the park's history was hit by Nashville's Joey Wendle four games later on April 21 against the Oklahoma City Dodgers.[41]

Tickets for the home opener, which went on sale March 23, sold out in approximately 15 minutes.[42] Though berm and standing-room-only tickets are normally sold only on the day of games, the team began selling these in advance of the first game due to high demand.[42] Paid attendance for the first game was a standing-room only crowd of 10,459.[39] Before the game, Mayor Karl Dean threw out the ceremonial first pitch.[39] "The Star-Spangled Banner" was performed by Charles Esten (a star of the television series Nashville), who also sang at the park's ribbon-cutting ceremony earlier in the day.[39] Also present at the ribbon-cutting were team owners Masahiro Honzawa and Frank Ward, Pacific Coast League (PCL) president Branch B. Rickey, Oakland Athletics president Michael Crowley, Mayor Dean, and members of the Metro Council who voted to approve financing for the stadium.[14] The Sounds were, at this time, members of the PCL and the Triple-A affiliate of Major League Baseball's (MLB) Oakland Athletics.[39]

By the All-Star break in mid-July, attendance had reached 332,604, a higher attendance than in the entire 2014 season at Greer Stadium, which had totaled 323,961 people over 66 games. At the end of the 71-game 2015 season, 565,548 people had attended a game at First Tennessee Park, for an average attendance of 7,965 per game, compared to 4,909 per game for the last season at Greer.[43][44] The Sounds' June 4 game against the Salt Lake Bees was the first event to be nationally televised from the ballpark.[45] Shown live on the CBS Sports Network as a part of Minor League Baseball's National Game of the Week programming, Nashville was defeated by Salt Lake, 4–2, before a sellout crowd of 10,610.[46]

In addition to other between-innings entertainment at the park, such as games and giveaways, the Sounds added the Country Legends Race in 2016. It is similar to major league mascot races, such as the Sausage Race and Presidents Race. During the middle of the fifth inning, people in oversized foam caricature costumes depicting country musicians Johnny Cash, George Jones, Reba McEntire, and Dolly Parton race around the warning track from center field, through the visiting bullpen, and to the beginning of the first base dugout.[47][48]

The two-year-old stadium was home to its first postseason baseball in 2016 when the American Conference Southern Division champion Sounds hosted Games Three, Four, and Five of the PCL American Conference championship against Oklahoma City. The Sounds won the first game, 6–5, but lost the next two games and the conference championship to the Dodgers, 7–1 and 10–9.[49]

The Sounds hosted an exhibition game against the Texas Rangers, their MLB affiliate, on March 24, 2019. Players appearing in the game for Texas included Delino DeShields Jr., Nomar Mazara, Hunter Pence, Ronald Guzmán, Isiah Kiner-Falefa, Logan Forsythe, Shawn Kelley, and José Leclerc. In a close game, the Sounds defeated the Rangers, 4–3.[50] Nashville's Preston Beck scored the winning run in the bottom of the sixth inning with a two-run homer driving in Eli White.[50] The attendance of 11,824 fans set a new ballpark single-game attendance record.[50]

Nashville played its final game in the Pacific Coast League on September 2, 2019. On the last day of the season before a Labor Day crowd of 9,987, the Sounds defeated the San Antonio Missions, 6–5, when Matt Davidson hit a 13th-inning, walk-off sacrifice fly to center field that allowed Andy Ibáñez to score from third base.[51] The start of the 2020 season was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic before being cancelled on June 30.[52][53] Following the 2020 season, Major League Baseball assumed control of Minor League Baseball in a move to increase player salaries, modernize facility standards, and reduce travel. Triple-A affiliations were rearranged to situate those teams closer to their major league parent clubs. The Sounds reaffiliated with the Milwaukee Brewers and were placed in the Triple-A East.[54] The ballpark hosted its first game in the new league on May 11, 2021, in which the visiting Memphis Redbirds defeated the Sounds, 18–6.[55] Capacity for the first three games was limited to 40 percent, but it was raised to nearly 100 percent on May 14.[56] The Sounds led all of Minor League Baseball in 2021 in total and average attendance with 436,868 people attending games at First Horizon Park, for an average attendance of 6,721 per game.[57]

In 2022, the Triple-A East became known as the International League, the name historically used by the regional circuit prior to the 2021 reorganization.[58] Nashville began play in the renamed league on April 5 with a win at home against the Durham Bulls, 5–4.[59] The single-game ballpark attendance record of 12,409 was set on July 16 for a game between Nashville and Memphis, a 10–0 loss.[8] The Sounds again led the minors in total attendance (555,576) while having the fourth-highest average (7,611) in 2022.[60]

The ballpark was the site of a no-hitter on May 3, 2024, when the visiting Norfolk Tides allowed no hits against the Sounds in a 2–0 Nashville loss. The feat was accomplished by starting pitcher Chayce McDermott (6.2 IP) and relievers Nolan Hoffman (1.1 IP) and Kaleb Ort (1 IP). McDermott walked two batters in the seventh inning accounting for the only Nashville baserunners.[61]

Soccer

[edit]

Nashville SC, an expansion soccer team of the United Soccer League, played the majority of their first two seasons (2018–2019) at First Tennessee Park.[62][63] The club competed in a preseason exhibition Major League Soccer (MLS) match against Atlanta United FC on February 10, 2018, in the first-ever soccer match played at the park.[64] Nashville was defeated amid a rainstorm by Atlanta, 3–1, in front of a crowd of 9,059 people.[65] The park's first goal was scored by Atlanta forward Josef Martínez in the 58th minute. Ropapa Mensah, the youngest player on the Nashville squad, scored the first goal in franchise history in the 64th minute.[66] Nashville's first regular-season home match, scheduled for March 24 versus the Pittsburgh Riverhounds, was moved to Nissan Stadium to accommodate a greater number of fans.[67] Their second home match was played at First Tennessee Park on April 7 against the Charlotte Independence before 7,487 people. Nashville won, 2–0, on forward Alan Winn's goal in the 24th minute; Mensah added a second goal in the 91st minute.[68] The team's highest attendance occurred on October 13 when 9,083 fans watched Nashville play to a 3–3 draw versus FC Cincinnati in the season finale.[69] Nashville SC's 2018 attendance totaled 125,390 over 15 games at the ballpark, with an average attendance of 8,359 per game.[70]

In preparation for the 2019 season, Nashville SC competed in a preseason friendly against MLS side New York City FC on February 22.[71] Nashville fell to New York, 2–0, in the rain-soaked match attended by 5,384.[72] The club's May 8 match against the Tampa Bay Rowdies, a 1–0 loss, was shown live on ESPN2 as the first-ever nationally televised regular-season USL Championship game.[73] Over 15 regular-season games at the facility, Nashville SC's 2019 attendance totaled 96,837, with an average of 6,456 per game.[74] Having qualified for the 2019 USL Championship Playoffs, Nashville SC played their quarterfinal and semifinal round matches at First Tennessee Park. They won the quarterfinals, 3–1, against the Charleston Battery, but lost the semifinals to Indy Eleven, 1–0.[74] Over two seasons of play, the club's total attendance was 222,227, with an average of 7,408 per match.[70][74] Including postseason play, their total attendance was 232,654, an average of 7,270 per match.[70][74] The club left for Nissan Stadium after 2019 in conjunction with its 2020 ascension to MLS.[75]

Other events

[edit]The first non-baseball event held at First Horizon Park was the City of Hope Celebrity Softball Game in 2015. Started in 1990, the event was played during Nashville's CMA Music Festival, and was previously held at Greer Stadium from 1991 to 2014 before moving to the new facility from 2015 to 2018. Two teams of country music stars representing the Grand Ole Opry and iHeartRadio competed, with all proceeds going to fund the research and treatment of cancer, diabetes, and other life-threatening diseases. Participants included Carrie Underwood, Darius Rucker, Florida Georgia Line, Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan, and Vince Gill.[76] Since 2021, the ballpark has hosted the Rock-N-Jock Celebrity Softball Game in which a team of musicians and other celebrities competed against a team of athletes to support Folds of Honor, a charitable organization that provides educational scholarships to the spouses and children of fallen and disabled service-members.[77][78][79] Among those competing in the inaugural event were Tennessee Titans players A. J. Brown and Taylor Lewan; Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee Terry Bradshaw; Cy Young Award winner and former Sound Barry Zito; country musicians Walker Hayes and Chris Lane; and comedian Jeff Dye.[77]

On March 29, 2016, the Vanderbilt Commodores and Belmont Bruins became the first collegiate baseball teams to play at First Horizon Park.[80] The Commodores defeated the Bruins, 8–2, in front of a crowd of 3,782 people.[81] Vanderbilt, Belmont, and the Lipscomb Bisons have since played subsequent games at the ballpark.[82] It has also hosted other sporting events such as the Nitro Circus, an extreme sports show featuring athletes performing BMX and freestyle motocross jumps and stunts.[83] Since 2016, the stadium has been included in the course of the Rock 'n' Roll Nashville Marathon. Runners participating in the full marathon take a complete a lap around the field's warning track and run past the facility on all four sides, while those in half-marathon run by only one side of the ballpark.[84]

First Horizon Park will host MLB Home Run Derby X on August 31, 2024. The competition pits two teams of three hitters apiece against each other as teams vie for points earned by hitting home runs or catching balls that fall short of clearing the outfield wall. Participants include former MLB players Andruw Jones and Nick Swisher.[85]

The stadium has been home to numerous non-sports events, such as food and drink festivals, since its opening. The first of these was the Nashville Brew Festival, held on October 3, 2015,[80] which featured over 50 breweries offering unlimited samples with paid admission.[86] Other events include the Big Guitar Brewfest, first held in 2016 and named in reference to the large guitar-shaped scoreboard,[87] and 2021's Blended Nashville, a music, food, and wine festival that included performances by Kaskade, Ludacris, and Lil Jon.[88] The Nashville-based American rock band Kings of Leon, with opener Dawes, performed on September 29, 2017, in the first concert held at the ballpark.[89] From November 22 to December 31, 2019, the stadium was the site of GLOW Nashville, a Christmas experience spanning the field and concourse. Attractions included displays of more than four million lights, sculptures, an over 100 ft-tall (30 m) Christmas tree, a three-story ice skating rink, a tube park, igloos, live entertainment, a market with local craft vendors, photos with Santa Claus, and story time with Mrs. Claus.[90][91] Enchant, a similar event, was planned for the 2022 Christmas season.[92]

Facilities

[edit]Design

[edit]

After Sulphur Dell was dismantled on April 16, 1969, the ballpark's sunken field was filled in with rock, dirt, and the remains of the demolished Andrew Jackson Hotel.[93][94] It was then converted to a number of state-owned parking lots for the nearby Tennessee State Capitol.[3] While Sulphur Dell was nestled in an area that was home to the city's garbage dump, stockyards, the Atlantic Ice House building, and various warehouses,[95][96] First Horizon Park is now surrounded by new apartments, parking ramps, and restaurants.[3] The facade at the home plate entrance on the stadium's north side is constructed from cast ultra-high-performance concrete planks, zinc panels, and an array of windows that stretches across the full width of the entrance.[97] To the south of the stadium, beyond the outfield wall, is an area that connects the city's Cumberland River Greenway to the Bicentennial Mall Greenway.[35] It will be open to the public on non-game days after the surrounding apartment buildings and retail spaces are completed.[7][98]

The grandstand has a 24-to-36 ft (7.3-to-11.0 m) wide concourse that wraps around the playing field. The field is recessed 17 ft (5.2 m) below the street-level concourse so it can be viewed from the entrances and seats.[99][100] Most of the on-field action can be viewed from the concourse; televisions showing live feeds of the game are located there. The seating bowl provides views of Nashville's skyline to the south.[3]

Because it is located on a flood plain, the ballpark was built to withstand a 100-year flood. Before its redevelopment, the area, including the original Sulphur Dell ballpark, was prone to regular flooding from the nearby Cumberland River and it flooded during the 2010 Tennessee floods. To prevent water damage, the grandstand has an acrylic floor covering and the field-level suites are equipped with detachable floor boards, food-service tables mounted on casters, and raised floor outlets and electrical switches.[3]

The ballpark's design is inspired by Nashville's heritage, as design elements throughout the park incorporate musical and baseball imagery to connect the park with the city's past.[97] Directional signs are accompanied by information about former Nashville players such as Al Maul, Tom Rogers, and Turkey Stearnes.[101] The park's suites include displays about Sulphur Dell, the Nashville Vols, a minor league team that played there from 1901 to 1961, and in 1963, and other past teams from Nashville. The back of the outfield wall's green metal batter's eye has a tin sign marking the former location of Sulphur Dell's marquee declaring, "Site of Sulphur Dell, Baseball's Most Historic Park, 1870–1963".[101] A series of nine vertical panels by the right field greenway provide information on the history of baseball in Nashville from the 1860s through 1963.[102] Another five panels beyond left field detail facts about the prehistory of the site.[103] Light stanchions on the grandstand and in the outfield resemble the lights installed at Sulphur Dell.[3] Details including guitar pick-shaped seating signage and the use of the Sounds' colors identify the ballpark with Nashville's country music heritage and reflect the visual identity of the team.[104]

Before the ballpark's second season in 2016, additional safety netting was added behind home plate, which extended the protective netting to cover the seating area behind both dugouts.[105] This was extended further down the left and right field lines prior to the 2024 season.[106] Additionally, padding was added to the walls surrounding the playing surface and the outfield wall padding was replaced to meet Minor League Baseball facility standards.[106]

Playing field and dimensions

[edit]

The initial playing surface was covered with 100,000 sq ft (9,300 m2) of Bermuda Tifway 419 grass sod that was grown on a farm in San Antonio, Texas, then over-seeded with 1,000 lb (450 kg) of perennial rye-grass.[107] Over 13,000 sq ft (1,200 m2) of red clay infield soil was brought in from Laceys Spring, Alabama.[14] The warning track surrounding the field is made of 21,000 sq ft (2,000 m2) of crushed red shale on top of 5,000 short tons (4,500 metric tons) of sand and 44,000 cu ft (1,200 m3) of gravel.[26] The field is equipped with a drainage system capable of draining 10 in (25 cm) of water per hour.[7] A new field of Latitude 36 Bermudagrass was installed over the 2019–20 offseason following five years of use and the departure of Nashville SC.[4][108]

The distance from home plate to the outfield wall ranges from 330 ft (100 m) in left field, 403 ft (123 m) in center field, and 310 ft (94 m) in right field.[109] The right field wall was set at this shorter-than-normal distance to pay homage to Sulphur Dell's short right field fence that measured just 262 ft (80 m).[110][111] The backstop is approximately 50 ft (15 m) behind home plate.[99] The field is set 17 ft (5.2 m) below the street-level concourse.[99]

The dugouts, which measure 88 ft (27 m) by 16 ft (4.9 m), are large enough to accommodate each team's staff without the need for relief pitchers to sit in the bullpens.[14] The Sounds' dugout is located on the third-base side; the visiting team's is located on the first-base side.[14] Bullpens are located in foul territory along the left-field and right-field lines near the corners of the outfield wall.[14] The home clubhouse has wooden lockers, two couches, three card tables, and a center table.[112] There is an attached kitchen with two full-size refrigerators and room for hot and cold catering.[112] Other player amenities include large, indoor batting cages, a fully equipped workout room, and a family room for players' partners and children.[3][112] In 2016, the umpire dressing room was named after former Major League Baseball umpire and Nashville native Chuck Meriwether.[113]

Since its first season, the facility's park factors have been significantly lower than those at other ballparks in the Pacific Coast League and across Triple-A baseball, giving it a reputation as a pitcher's park. In 2015, First Tennessee Park had the lowest run and home-run factors of all 30 Triple-A teams, and its hits factor was the fifth-lowest in Triple-A and the fourth-lowest in the 16-team PCL.[114] In 2016, it had the lowest home-run factors in Triple-A, its runs factor was the sixth-lowest in Triple-A and fifth-lowest in the PCL, and its hits factor was the seventh-lowest in Triple-A and the sixth-lowest in the PCL.[115] From 2017 to 2019, the park was tied for the lowest Triple-A home-run factors, its runs factor was tied for the second-lowest in Triple-A, and its hits factor was tied for the fourth-lowest in Triple-A and the tied for the third-lowest in the PCL.[116]

The ballpark was selected to win the 2016 Tennessee Turfgrass Association's Professional Sports Field of the Year Award, recognizing it as the state's top professional sports field with a natural grass playing surface.[117]

When configured for soccer, one side of the field ran parallel to the first base line with the other sideline running from left to right field. One goal was located past the third base dugout, and the other was near the right-center field wall. The pitcher's mound was removed, and the infield dirt and portions of the warning track were sodded over.[62] The pitch measured 115 yd × 72 yd (105 m × 66 m).[9]

Scoreboard

[edit]

One of Greer Stadium's most distinctive features was its guitar-shaped scoreboard.[118] After First Tennessee Park was approved, the team announced it would not be relocating the original Greer scoreboard, which was technologically outdated and difficult to maintain, to the new facility.[119] While plans for the new ballpark's scoreboard were initially undisclosed, following overwhelming support for Greer's guitar from the community, the team announced plans for the installation of a larger, more modern guitar-shaped scoreboard.[119] The new scoreboard, installed beyond the right-center field wall on the concourse, was designed by TS Sports in conjunction with Panasonic.[109][120]

The scoreboard, which has a 4,200 sq ft (390 m2) HD LED screen, is located in the middle of the right-field concourse.[120] Excluding the borders of the body and headstock, the surface of the guitar is composed of LED screens. Overall, the guitar measures 142 by 55 ft (43 by 17 m),[97] its body display is 50.4 by 66.14 ft (15.36 by 20.16 m), the headstock display is 12.6 by 25.2 ft (3.8 by 7.7 m), and the six tuning pegs are 6.3 by 4.2 ft (1.9 by 1.3 m) each.[109] Whereas the scoreboard at Greer was capable of displaying only basic in-game information such as the line score, count, and brief player statistics, the new version can display colorful graphics and animations, photographs, live and recorded video, instant replays, the batting order, fielding positions, and expanded statistics.[120]

As well as the main scoreboard, the ballpark has three additional LED displays. A display in the left-center field wall is used for showing in-game pitching statistics, upcoming batters, and advertisements. LED ribbon boards are installed on the facings of each side of the upper deck; these are used to display the inning, score, count, and advertisements.[7] The stadium's three pitch clocks are located on the straightaway center-field wall and on each side of the backstop.[101]

In the early hours of March 3, 2020, an EF3 tornado touched down in Nashville's Germantown area, just blocks north of the stadium.[121] Though the ballpark did not suffer any major structural damage,[122] the guitar scoreboard was extensively damaged. The entire back of the guitar's body as well as the front and back of its neck were ripped off, damaging the wiring system.[123] The neck was replaced with an LED display.[124]

Seating

[edit]

The lower seating bowl is divided into 25 sections and wraps around the playing field from just past one foul pole to just past the other.[125] The second level has 16 sections of seating that begin behind third base and wrap around to first base.[125] The last nine rows, from row M, on the first level between the dugouts are sheltered by the upper deck. Seats on both levels are traditional, plastic stadium-style chairs.[126] All lower-level seats behind home plate, seats behind and between the dugouts through row P, and all second-level seats have padded seat cushions.[126] Seats in the three center upper-deck sections behind home plate and all second-level suites also have padded seat backs. A grass berm that can accommodate 1,500 spectators is located beyond the left-center field wall.[7]

The park has several areas reserved for small and large groups. Four field-level suites, each with 33 exterior seats and additional interior space to accommodate up to 50 people, are located directly behind home plate.[3][127] The second level has 18 suites, each accommodating up to 20 people, with 4 indoor drink rail seats and 13 outdoor seats in front.[14][128] Two covered party decks are located on the second level—one at each end—both of which can accommodate up to 100 people each.[129] Between the left-field foul pole and the outfield berm lies a group area which can accommodate up to 500 individuals. This area consists of a covered picnic area and lounge furniture.[106][130] A section of 4-top tables—semi-circular tables surrounded by four chairs—that can accommodate 108 people at 27 tables is located at the end of the lower seating bowl in right field near a specialty concession area called The Band Box.[131] A small private party area is located in the power alley in front of The Band Box and can accommodate up to 35 people at chairs and 4-top tables.[132] Next to this, and directly in front of the scoreboard, is a 200-person group picnic area with standing room and stadium seats with drink rails.[133] A 4,000 sq ft (370 m2) climate-controlled party tent capable of holding over 500 people is located on the first-base concourse.[134]

Concessions

[edit]

Four permanent concession stands and several portable carts located on the concourse offer traditional ballpark foods including hot dogs, corn dogs, pizza, nachos, soft pretzels, popcorn, and ice cream.[14] Each stand also serves foods unique to and common in Nashville and the South, including Nashville hot chicken and pulled pork barbecue sandwiches.[135][136] The stadium's second level has a bar, lounge, and concessions area with views of the field; it is accessible only by those with suite, party-deck, or upper-deck tickets.[137][138] Certain menu items, such as prime rib tacos, sliders, and onion rings are only available on the second level.[136]

The Band Box

[edit]Another specialty concession area is The Band Box, a 4,000 sq ft (370 m2) outdoor restaurant and bar located on the right-field concourse.[139] The restaurant serves variations on traditional ballpark foods including cheeseburgers, chicken sandwiches, jalapeño corn fritters, smoked chicken nachos, quinoa chopped salads, and local draft craft beer.[139] It is accompanied by a 150-person bar to its rear overlooking right field.[14][97][140] The bar has an adjoining lounge area with couches, televisions, ping pong, cornhole, foosball, and shuffleboard, which is open to all game ticket-holders.[101][141] Patrons in the adjacent 4-top seating section can order food and drinks from The Band Box and have items delivered to their seats.[139] On June 28, 2016, a 9-hole miniature golf course, called The Country Club at The Band Box, opened behind the restaurant between the bar and Fifth Avenue. Each of the nine holes exhibits art from different local or regional artists. It is open to game attendees for an additional $5 playing fee.[142]

Parking

[edit]

A 1,000-car above-ground parking garage, owned by the state, is located south of the stadium's center-field and right-field entrances on Harrison Street between Fourth and Fifth Avenues.[143] As the garage is used by state employees during the day, game attendees are only able to use it for evening and weekend games.[144] Other state-owned free parking lots and paid private lots are located in the vicinity.[143] The Metro Transit Authority's Music City Circuit provides bus service to and from a drop-off site at Fifth Avenue and Harrison Street. Nashville BCycle, the city's bike-share program, has a station outside the ballpark.[145]

Attendance records

[edit]First Horizon Park's single-game attendance record was set on July 16, 2022, during a game between the Sounds and the Memphis Redbirds in front of a sellout crowd of 12,409 people.[8] The park's season attendance record of 603,135 was set in 2018, while its average attendance record (8,861) was set in 2017. Nashville led all of Minor League Baseball in 2021 in total attendance (436,868) and average attendance (6,721).[57] In 2022, the Sounds again led the minors in total attendance (555,576) while having the fourth-highest average (7,611).[60] Attendance records through the completion of the 2023 season are as follows.

Single-game attendance

[edit]Bold indicates the winner of each game.

| Rank | Attendance | Date | Game result | Promotion(s) | Ref(s). |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12,409 | July 16, 2022 | Memphis Redbirds – 10, Nashville Sounds – 0 | Star Wars Night / lightsaber giveaway / Boy Scout Night | [146][147] |

| 2 | 12,140 | August 13, 2022 | Gwinnett Stripers – 7, Nashville Sounds – 6 (10 inn.) | "Margaritaville" Night / Hawaiian shirt giveaway | [148][149] |

| 3 | 11,824 | March 24, 2019 | Texas Rangers – 3, Nashville Sounds – 4 | MLB exhibition game | [150] |

| 4 | 11,764 | July 3, 2017 | Oklahoma City Dodgers – 6, Nashville Sounds – 5 | Independence Day celebration / Don Mattingly throwback jersey T-shirt giveaway | [151][152] |

| 5 | 11,759 | July 3, 2016 | Oklahoma City Dodgers – 4, Nashville Sounds – 1 | Independence Day celebration / Military Sunday | [153][154] |

| 6 | 11,692 | September 2, 2018 | Memphis Redbirds – 2, Nashville Sounds – 1 | Memphis Grizzlies Night / Military Sunday / tote bag giveaway / post-game fireworks | [155][156] |

| 7 | 11,691 | July 4, 2018 | Iowa Cubs – 6, Nashville Sounds – 2 | Independence Day celebration / Bobby Wahl T-shirt giveaway | [157][158] |

| 8 | 11,686 | July 4, 2021 | Louisville Bats – 3, Nashville Sounds – 9 | Independence Day celebration | [159][160] |

| 9 | 11,684 | June 25, 2016 | Omaha Storm Chasers – 4, Nashville Sounds – 2 | Star Wars Night | [161][154] |

| 10 | 11,678 | June 17, 2017 | New Orleans Baby Cakes – 2, Nashville Sounds – 3 | Cancer Awareness Night / "Strikeout Cancer" T-shirt giveaway / Lego Play Ball Tour | [162][163] |

Season attendance

[edit]The Sounds are members of the 20-team International League.[58] Since 2022, their seasons have consisted of 75 scheduled home games,[164][165] while there were 65 scheduled in 2021.[166] Nashville previously competed in the 16-team Pacific Coast League from 2015 to 2020.[167] Their seasons consisted of 72 scheduled home games in 2015 and 2016,[168][169] 71 games in 2017,[170] and 70 games from 2018 to 2020.[171][172]

| Rank | Season | Total attendance | Openings | Average attendance | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Rank | Openings | Rank | Average | Rank | |||

| 1 | 2018 | 603,135 | 2nd | 69 | 2nd (tie) | 8,741 | 2nd | [173] |

| 2 | 2017 | 593,679 | 2nd | 67 | 5th (tie) | 8,861 | 1st | [174] |

| 3 | 2019 | 578,291 | 3rd | 67 | 4th (tie) | 8,631 | 2nd | [175] |

| 4 | 2015 | 565,548 | 4th | 71 | 2nd (tie) | 7,965 | 5th | [176] |

| 5 | 2023 | 556,962 | 3rd | 72 | 3rd (tie) | 7,736 | 4th | [177] |

| 6 | 2022 | 555,576 | 1st | 73 | 3rd (tie) | 7,611 | 3rd | [178] |

| 7 | 2016 | 504,060 | 6th | 71 | 2nd (tie) | 7,099 | 7th | [179] |

| 8 | 2021 | 436,868 | 1st | 65 | 1st (tie) | 6,721 | 1st | [57] |

| 9 | 2020 | Season cancelled (COVID-19 pandemic)[53] | [180] | |||||

| Totals | — | 4,394,119 | — | 555 | — | 7,917 | — | — |

Popular culture

[edit]The ballpark has been featured in two music videos. Cole Swindell's "Middle of a Memory" (2016) includes shots of Swindell in the audience watching a Nashville Sounds game as well as footage of the game and an appearance by the team's mascot, Booster.[181] Former Sounds pitcher Barry Zito's music video for "That Sound" (2017), which is about Sounds games, is composed almost entirely of footage of Nashville's games, players, and fans shot at the stadium during the 2016 season.[182] Portions of the music video for Zito's "Ballpark Kids" (2020) were also filmed at the stadium.[183]

Trisha Yearwood filmed scenes for the "Tailgaiting" episode of Food Network's Trisha's Southern Kitchen at the ballpark on May 31, 2016.[184][185] The August 5, 2017, episode of CMT Hot 20 Countdown was filmed at the stadium on July 25 and included performances by country musicians Michael Ray and Chris Lane from before that day's game.[186] Segments for a series of season 36 (2018–2019) episodes of Wheel of Fortune, including host Pat Sajak throwing out the first pitch, were shot at the ballpark on May 4, 2018.[187]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Specific

- ^ "Sounds Woes Continue". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. July 28, 2015. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ a b "Mayor, Nashville Sounds Celebrate Groundbreaking for New Ballpark". Nashville.gov. Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County, Tennessee. January 27, 2014. Archived from the original on May 1, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Reichard, Kevin (April 20, 2015). "First Tennessee Park / Nashville Sounds". Ballpark Digest. August Publications. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Nashville Sounds Media Guide 2022, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d "Audit of the First Tennessee Ballpark Construction Project" (PDF). Metropolitan Nashville Office of Internal Audit. April 24, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Fact Sheet – Highlights of First Tennessee Park Construction Tour". Nashville.gov. Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County, Tennessee. February 4, 2015. Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Sounds Break First Horizon Park Attendance Record". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. July 16, 2022. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Organ, Mike (September 12, 2017). "Nashville SC: Everything You Need to Know". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ a b "First Tennessee to Put Name on Proposed Sounds Stadium". Nashville Business Journal. November 21, 2003. Archived from the original on April 21, 2015.

- ^ a b Tarica, Andrew (February 8, 2006). "Sounds Get New Park on the River". Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Carter, Cindy (May 22, 2007). "Downtown Nashville Property Up for Bids Again". WSMV. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- ^ Stults, Rachel (April 11, 2008). "Sounds Cover All the Bases to Ready Ballpark for Opener". The Tennessean. Nashville. p. 1A. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ammenheuser, David. "Coming Home to Sulphur Dell". The Tennessean. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- ^ "The Nashville Ballpark: Ballpark Site Evaluation Study" (PDF). The Business Journals. Populous. November 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Fact Sheet – Sulphur Dell Ballpark Proposal". Nashville.gov. Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County, Tennessee. November 11, 2013. Archived from the original on December 5, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c Garrison, Joey (March 18, 2015). "Nashville Sounds Stadium to Cost $10M More Than Expected". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Boyer, E. J. (March 23, 2015). "Want to Attend the Sounds' First Tennessee Park Home Opener? It'll cost you". Nashville Business Journal. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Mazza, Sandy (June 19, 2018). "Retail Complex Next to First Tennessee Park OK'd for Development". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ "Ballpark Building Lands Bowling Business". Nashville Post. Nashville. June 19, 2019. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- ^ Leimkuehler, Matthew (June 1, 2020). "Brooklyn Bowl Nashville Opens This Week to Limited Dining Capacity". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Burnett, Marq (June 16, 2020). "Sports Bar Next to Sounds' Stadium to Open This Month". Nashville Business Journal. Archived from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Williams, William (February 16, 2022). "Work Starts on Development Next to Ballpark". Nashville Post. Archived from the original on October 17, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "Real Estate Notes: Developer Buys Ballpark-area Site for $3.45M". Nashville Post. September 23, 2014. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Hale, Steven (December 4, 2013). "Sounds Ballpark Deal Rounds Second, Headed for Final Vote Next Week". Nashville Scene. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Baseball Has Come Home". Inside Pitch. Vol. 4, no. 1. Nashville. April 17, 2015. pp. 8–19.

- ^ McCalvy, Adam (September 17, 2014). "Melvin Irked Over Breakup With Triple-A Affiliate". Milwaukee Brewers. Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- ^ Tamburin, Adam (April 4, 2014). "Nashville Ballpark Build Unearths Ancient Finds". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- ^ Barnes, Todd (November 20, 2014). "Tennessee State Museum to House Sulphur Dell Artifacts". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- ^ Traughber, Bill (2017). Nashville Baseball History: From Sulphur Dell to the Sounds. South Orange, New Jersey: Summer Games Books. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-938545-83-2.

- ^ "Relics of the Mound Builders". The Daily American. Nashville. March 1, 1885. p. 4. Archived from the original on April 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Garrison, Joey (November 19, 2014). "New Sounds Stadium Adds $5M to Price Tag". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "LEED BD+C: New Construction v3 – LEED 2009: First Tennessee Park". U.S. Green Building Council. April 2015. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Garrison, Joey (April 14, 2015). "New Sounds Stadium Earns LEED Silver Certification". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ a b "Cumberland River Greenway: Downtown" (PDF). Greenways For Nashville. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ Boyer, E. J. (April 22, 2014). "First Tennessee Bank Buys Naming Rights to New Sounds Stadium". Nashville Business Journal. Archived from the original on May 16, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ "Nashville Sounds' Home to Become First Horizon Park". Ballpark Digest. August 22, 2019. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ Holman, Abby (October 14, 2019). "Welcome To First Horizon Park". Sound Bytes Blog. Major League Baseball. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Sounds Walk-Off in Home Opener". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. April 18, 2015. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Sky Sox vs. Sounds Box Score 04/17/15". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. April 17, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ "Sounds Bested by Dodgers In Series Opener". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. April 21, 2015. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Herron, Jennifer (March 30, 2015). "Box Seats Sell out for Opening Night at Sounds' New Stadium". WSMV. Nashville. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015.

- ^ Ammenheuser, David (July 16, 2015). "Sounds Have Already Bypassed 2014 Attendance Mark". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

- ^ "Nashville Drops Home Finale". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. September 3, 2015. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Sounds' June 4th Home Game to be Nationally Televised". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. April 21, 2015. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Bees vs. Sounds Box Score 06/04/15". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. June 4, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Country Legends Race". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ @nashvillesounds (April 10, 2018). "Introducing our newest Country Legend racer...@DollyParton! She debuted with a W #CrankItRED Special thanks to @FirstTennessee for making all of our races possible!" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Nashville Sounds Media Guide 2022, p. 189.

- ^ a b c "Sounds Edge Rangers in Front of Record-Breaking Crowd at First Tennessee Park". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. March 24, 2019. Archived from the original on March 8, 2022. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Missions vs. Sounds Box Score 09/02/19". Minor League Baseball. September 2, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ "A Message From Pat O'Conner". Minor League Baseball. March 13, 2020. Archived from the original on January 2, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "2020 Minor League Baseball Season Shelved". Minor League Baseball. June 30, 2020. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Mayo, Jonathan (February 12, 2021). "MLB Announces New Minors Teams, Leagues". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Redbirds vs. Sounds Wrapup 05/11/21". Minor League Baseball. May 11, 2021. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Organ, Mike (May 14, 2021). "Facial Coverings No Longer Required for Nashville Sounds Games at First Horizon Park". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Sounds Lead Minor League Baseball in 2021 Attendance". Nashville Post. Nashville. September 28, 2021. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ^ a b "Historical League Names to Return in 2022". Minor League Baseball. March 16, 2022. Archived from the original on March 25, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Bulls 4, Sounds 5 (Final Score)". Minor League Baseball. April 5, 2022. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Reichard, Kevin (October 12, 2022). "2022 MiLB Attendance by Total". Ballpark Digest. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "Gameday: Tides 2, Sounds 0 Final Score (05/03/2024)". Minor League Baseball. May 3, 2024. Archived from the original on May 4, 2024. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ a b Garrison, Joey (August 23, 2017). "Renderings Show How Pro Soccer Will Work at the Nashville Sounds' First Tennessee Park". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Boclair, David (May 16, 2019). "Nashville SC Moves Two Matches to Nissan Stadium". Nashville Post. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ "Nashville SC to Host Atlanta United in Historic Exhibition". USL Soccer. November 28, 2017. Archived from the original on December 6, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ Roberson, Doug (February 10, 2018). "Atlanta United Wins Preseason Opener". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ Luis, Torres (February 10, 2018). "Ropapa Mensah Scores the First Goal for Nashville SC Franchise". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ "Nashville SC League Home Opener Moved to Nissan Stadium". Nashville SC. February 12, 2018. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ Cranford, Aaron (April 7, 2018). "Nashville Tops Independence in Front of 7,487". USL Soccer. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Sights & Sounds – Nashville, Cincinnati Bring the Park Down". USL Soccer. October 14, 2018. Archived from the original on October 18, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Nashville SC 2018 Schedule". USL Championship. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- ^ "2019 Schedule". Nashville SC. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- ^ "Nashville SC Drops Rainy Preseason Friendly to MLS' New York City FC at First Tennessee Park: Nissan Recap". Nashville SC. February 22, 2019. Archived from the original on February 24, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ "Nashville SC Meets the Midweek Blues, Falls 1–0 to Tampa Bay Rowdies: Nissan Recap". Nashville SC. May 8, 2019. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Nashville SC 2019 Schedule". USL Championship. Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ "Nashville SC Silent Auction to Benefit Vanderbilt Children's Hospital". Nashville Post. November 5, 2019. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- ^ "2015 Celebrity Softball Game: Event Info". City of Hope. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ a b "Nashville Sounds and Folds of Honor Announce Rock-N-Jock Celebrity Softball Game on June 3". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. May 13, 2021. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ "Rock'N Jock Celebrity Softball Game". Folds of Honor. 2022. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ "Rock N Jock Celebrity Softball Returns to First Horizon Park on June 5th". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. April 14, 2023. Archived from the original on October 6, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ a b Organ, Mike (October 25, 2015). "Vanderbilt to Play Belmont at First Tennessee Park". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Sparks, Adam (March 29, 2016). "Vanderbilt Wins First Tennessee Park's First College Game". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ "Defending National Champion Commodores Set to Play Two Games at First Horizon Par". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. February 13, 2020. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ "Nitro Circus Brings High-Adrenaline Live Entertainment Back With Explosive You Got This Tour to First Horizon Park". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. May 12, 2021. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "The Course". Rock 'n' Roll Nashville Marathon. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ "MLB Home Run Derby X". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. May 21, 2024. Archived from the original on May 21, 2024. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Todd, Jen (September 29, 2015). "Nashville Brew Festival Heads to First Tennessee Park". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Sounds to Host "Big Guitar Brewfest" on July 16". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. June 3, 2016. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Blended Festival - Austin Nashville San Diego". PR Newswire. Cision. August 10, 2021. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Kings of Leon 9/29". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. September 11, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ Gill, Joey (August 20, 2019). "GLOW Nashville Christmas Festival Promises to Deliver 'Brightest Christmas Experience'". WSMV. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- ^ Alfs, Lizzy (November 23, 2019). "Massive Holiday Event Unlike Any Other Debuts at First Tennessee Park". MSN. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Darby, McCarthy (August 20, 2022). "Christmas Fanatic? You Won't Want to Miss This: National Light Spectacular 'Enchant' Coming to Nashville". NewsChannel 5. Archived from the original on August 21, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Williams, F. M. (April 17, 1969). "Sad Day at the Dell, as 35 Say Farewell". The Tennseeean. Nashville. p. 54 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Nipper, Skip (March 16, 2015). "Nashville Bugs, Builders, and Ballpark Construction". 262 Down Right. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Nipper, Skip (2007). Baseball in Nashville. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0-7385-4391-8.

- ^ Nipper, Skip (October 24, 2013). "New Ballpark, New Opening Day, New Memories". 262 Down Right. Archived from the original on June 19, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Boyd, Steve (April 10, 2015). "12 Design Features Not to Miss on First Tennessee Park Opening Day". Populous. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015.

- ^ Reichard, Kevin (April 6, 2016). "Ballpark Village Pitched for First Tennessee Park". Ballpark Digest. August Publications. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c Ammenheuser, Dave (March 17, 2015). "12 Facts As First Tennessee Park Opener Nears". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Leonard, Mike (April 20, 2015). "First Tennessee Park: 7 Cool Environmental Features". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Hill, Benjamin (August 14, 2015). "Take a Tour of Nashville's New Ballpark". Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ Negro League Baseball in Tennessee. YouTube (Video). December 1, 2015. Event occurs at 2:26. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ "2016 Nashville Sounds A to Z". The Tennessean. Nashville. April 6, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ "First Tennessee Park Review". Stadium Journey. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015.

- ^ "Sounds Announce Enhanced Fan Safety Measures at First Tennessee Park". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. January 12, 2016. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Sounds Unveil Ballpark Upgrades at First Horizon Park". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. March 15, 2024. Archived from the original on March 15, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ Ammenheuser, Dave (March 19, 2015). "Sounds' New Stadium Now Has Turf, Home Plate". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Anderson, Kayla (June 24, 2020). "Watch: Sounds Set to Host 40-Game Baseball Season, Plan Is to Have Fans in Attendance". WKRN News 2. Archived from the original on July 10, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c "First Tennessee Park" (PDF). 2015 Nashville Sounds Media Guide. Minor League Baseball. 2015. p. 206. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2015.

- ^ Behind the Scenes with the Designers of First Tennessee Park. Populous (Video). April 10, 2015. Event occurs at 1:00. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Nipper, Skip (April 13, 2015). "History Made at Sulphur Dell". The Tennessean. Nashville. p. 4C – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Fox, David (June 18, 2015). "Basics Like Housing and Meals Remain a Challenge for Minor League Players, Even with a Spanking New Stadium". Nashville Scene. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015.

- ^ "Sounds to Name Umpire Dressing Room After Nashville Native Chuck Meriwether". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. May 5, 2016. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ Dykstra, Sam (October 23, 2015). "Toolshed: Final Triple-A Park Factors Review". International League News. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Dykstra, Sam (November 15, 2016). "Toolshed Stats: Triple-A Ballpark Factors". Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Dykstra, Sam (November 8, 2019). "Toolshed: Assessing Triple-A Park Factors". Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "First Tennessee Park Named Tennessee Turfgrass Association's Sports Field of the Year". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. January 11, 2017. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ Cole, Nick (April 22, 2014). "First Tennessee's Name Will Go on New Sounds Ballpark". The Tennessean. Nashville. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- ^ a b "Sounds to Have New Guitar Scoreboard in New Stadium". The Tennessean. Nashville. July 3, 2014. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Sounds, Mayor Unveil State-of-the-Art Guitar Scoreboard For First Tennessee Park". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. June 20, 2014. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "March 2–3, 2020 Tornadoes and Severe Weather". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Nashville, Tennessee. March 5, 2020. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- ^ Spedden, Zach (March 4, 2020). "No Structural Damage to First Horizon Park After Tornadoes". Ballpark Digest. August Publications. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- ^ Organ, Mike (March 5, 2020). "Tornado Caused Extensive Damage to Nashville Sounds' Iconic Guitar Scoreboard". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- ^ Bacharach, Erik (April 3, 2020). "How Tornado Damage and Coronavirus Affect Nashville Sounds". The Jackson Sun. Jackson. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Nashville Sounds Seating Map & Pricing". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on April 27, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "2015 Nashville Sounds Season Ticket Memberships" (PDF). Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "2018 Nashville Sounds Premium Group Hospitality & Outfield Picnics" (PDF). Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 21, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ "Nashville Sounds Club Suites". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Nashville Sounds Club Decks". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Nashville Sounds Hyundai Deck". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on March 15, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "Nashville Sounds George Dickel 4-Tops". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Nashville Sounds AMI Power Alley". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Nashville Sounds Vanderbilt Health Picnic Place". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "5th Ave Tent". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Centerplate and Nashville Sounds Give Fans More to Cheer About on Menus at the New First Tennessee Park". MarketWatch. April 17, 2015. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015.

- ^ "2017 Nashville Sounds Group Outings and Picnics" (PDF). Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Hill, Benjamin (October 12, 2015). "On the Road: My First Look at First Tennessee Park in Nashville". Minor League Baseball. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c White, Abby (March 30, 2015). "Take Me Out to The Band Box: Strategic Hospitality Partners With Nashville Sounds in New Restaurant". Nashville Scene. Nashville. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015.

- ^ Hill, Benjamin (October 13, 2015). "On the Road: Gourmet Nachos and Hot Chicken in Nashville". Minor League Baseball. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Wood, Tom (April 25, 2015). "Nashville Sounds Owner, Players Marvel at New Park". The Daily News. Memphis. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015.

- ^ "Miniature Golf Course Opens at First Tennessee Park". WKRN. June 29, 2016. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ a b "Parking Information". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on May 7, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ Ammenheuser, David (April 6, 2016). "Sounds' Opening Day: 5 Things to Know". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ Garrison, Joey (February 27, 2015). "Sounds' Parking Plan Relies On Shuttles, Walking, Transit". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ "Redbirds vs. Sounds Box Score 07/07/17". Minor League Baseball. July 16, 2022. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ "Sounds Welcome Cardinals Affiliate For Six-Game Series". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. July 7, 2022. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ "Stripers 7, Sounds 6 (Final Score) on Gameday". Minor League Baseball. August 13, 2022. Archived from the original on August 14, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ "First Place Nashville Sounds Host Braves Affiliate Beginning Tuesday, August 9". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. August 4, 2022. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ "Rangers vs. Sounds Box Score 03/24/19". Major League Baseball. March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ "Dodgers vs. Sounds Box Score 07/03/17". Minor League Baseball. July 3, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "Homestand Preview: June 26 – July 3". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. June 23, 2017. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "Dodgers vs. Sounds Box Score 07/03/16". Minor League Baseball. July 3, 2016. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "Sounds Begin Eight-Game Homestand Saturday". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. June 23, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "Redbirds vs. Sounds Box Score 09/02/18". Minor League Baseball. August 31, 2018. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ^ "Homestand Preview: August 31 – September 3". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. August 24, 2018. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ "Cubs vs. Sounds Box Score 07/04/18". Minor League Baseball. July 4, 2018. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ "Homestand Preview: July 4–8". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. June 29, 2018. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Bats vs. Sounds Box Score 07/04/21". Minor League Baseball. July 4, 2018. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "Sounds Begin 12-Game, 13-Day Homestand on Tuesday, June 22". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. June 16, 2021. Archived from the original on July 5, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "Storm Chasers vs. Sounds Box Score 06/25/16". Minor League Baseball. June 25, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "Baby Cakes vs. Sounds Box Score 06/17/17". Minor League Baseball. June 17, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "Homestand Preview: June 13 – June 20". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. June 12, 2017. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "Major League Baseball Adds Three Games to Sounds' 2022 Home Schedule". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. February 3, 2022. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "Sounds Announce 2023 Schedule". Minor League Baseball. August 29, 2022. Archived from the original on October 17, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ "2021 Triple-A East Standings". Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Pacific Coast League (AAA) Encyclopedia and History". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Sounds Release 2015 Schedule". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. September 25, 2014. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Nashville Sounds Release 2016 Season Promotional Schedule". Clarksville Online. March 8, 2016. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Sounds Announce 2017 Schedule". Minor League Baseball. December 15, 2016. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "Sounds Announce 2018 Home Schedule". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. August 3, 2017. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Sounds Announce 2019 Home Schedule". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. August 1, 2018. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "2018 Pacific Coast League Attendance". Pacific Coast League. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ "2017 Pacific Coast League Attendance". Pacific Coast League. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "2019 Pacific Coast League Attendance". Pacific Coast League. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "2015 Pacific Coast League Attendance". Pacific Coast League. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Reichard, Kevin (October 16, 2023). "2023 MiLB Attendance by League". Ballpark Digest. Archived from the original on October 17, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ Reichard, Kevin (October 12, 2022). "2022 MiLB Attendance by League". Ballpark Digest. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "2016 Pacific Coast League Attendance". Pacific Coast League. Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "2020 Pacific Coast League Attendance". Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on July 2, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Cole Swindell (2016). Middle of a Memory. YouTube (Music video). Event occurs at 1:31. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Barry Zito (2017). That Sound. YouTube (Music video). Nashville Sounds. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Kleinschmidt, Jessica (September 20, 2020). "Barry Zito Releases New Kid-inspired Baseball Song 'Ball Park Kids'". NBC Sports. Archived from the original on October 4, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Thanki, Juli (May 31, 2016). "Trisha Yearwood Delivers First Pitch, Anthem at Sounds Game". The Tennessean. Nashville. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ "Tailgaiting – Trisha's Southern Kitchen". Food Network. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ "Michael Ray and Chris Lane to Play at First Tennessee Park as Part of "CMT Hot 20 Countdown" Taping on Tuesday, July 25". Nashville Sounds. Minor League Baseball. July 21, 2017. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ Mojica, Adrian (2018). "Wheel of Fortune Coming to Nashville Sounds Game at First Tennessee Park". Fox 17. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- General

- Seely, Chad; Perry, Collin; Scopel, Doug (2022). 2022 Nashville Sounds Media Guide (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 5, 2022 – via Minor League Baseball.

External links

[edit]- 2015 establishments in Tennessee

- Baseball venues in Tennessee

- International League ballparks

- Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design basic silver certified buildings

- Minor league baseball venues

- Nashville SC

- Nashville Sounds

- Soccer venues in Tennessee

- Sports venues completed in 2015

- Sports venues in Nashville, Tennessee

- USL Championship stadiums