Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus

| Location | Field of Mars [1] |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′41″N 12°28′27″E / 41.894611°N 12.474239°E |

| Type | bas-relief |

| History | |

| Builder | Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus |

| Founded | Between 122 and 115 BC |

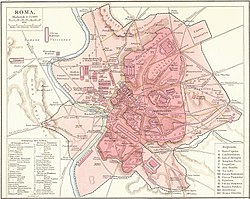

The Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus (more properly called the Statuary group base of Domitius Ahenobarbus) is a series of four sculpted marble plaques that probably decorated a base supporting cult statues in the cella of a Temple of Neptune located in Rome on the Field of Mars.

The frieze is dated to the end of the second century BC,[n 1] which makes it the second oldest Roman bas-relief currently known.[n 2] However, there is also a contemporaneous relief depicting a Roman naval bireme with armed marines,[1] from a temple of Palestrina built c. 120 BC.[2]

The sculpted panels are still visible today, with one portion on display at the Louvre (Ma 975[m 1]) and another at the Glyptothek in Munich (Inv. 239). A copy of this second piece can be seen at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

Context

[edit]The base was found in the Temple of Neptune built near the Circus Flaminius,[a 1][n 3] by the Field of Mars. Remains of this temple may have recently been discovered under the church of Santa Maria in Publicolis, but their identification remains uncertain.[3]

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]The reliefs seem to have been produced during the construction of a Temple of Neptune on the Field of Mars. A general, probably Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus, vowed to build a temple for the god of the sea after a naval victory, perhaps the one won off Samos in 129 or 128 BC against Aristonicus who had attempted to oppose the donation of Pergamon to Rome by the will of King Attalos III. The construction of the temple (or restoration of a pre-existing temple) only dates to 122 BC, the year in which Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus attained the consulship.[3][4]

The reliefs, from the base of the cult statue, which originally consisted only of mythological scenes were brought to completion after Domitius Ahenobarbus' censorship in 115 BC with a fourth panel. Other hypotheses however suggest the censorships of L. Valerius Flaccus and Marcus Antonius, who could equally be connected with the motifs of the reliefs.[5]

In 41 BC, Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus (descendant of the aforementioned), a supporter of the Republican party and of the assassins of Caesar had an aureus minted on the occasion of a victory over a supporter of Octavian, which featured the image of his ancestor on the obverse and a tetrastyle temple on the reverse, with the inscription NEPT CN DOMITIUS L F IMP (Cn. Domitius, son of Lucius, Imperator, to Neptune.[m 2]

Renaissance

[edit]The reliefs are mentioned in 1629 and 1631 after having been uncovered during the works undertaken by the Roman Santacroce family between 1598 and 1641, which included notably the construction and expansion of a palace near the Tiber by the architect Peparelli. The reliefs had been reused as decoration in the palace courtyard,[5] where they are attested in 1683.[6]

Description

[edit]

Despite their common name, the reliefs probably did not originally form part of an altar, but a large rectangular base (5.6 m long, 1.75 m wide, and 0.8 m high),[7] intended to support the cult statues.[3] These included works attributed to the Greek sculptor Scopas,[n 4] like the important statuary group featuring Neptune, Thetis, Achilles, the Nereids, Tritons and Phorcys with sea monsters and other fantastic creatures.[a 1]

The reliefs consist of two large panels on the long sides of the base and two smaller panels for the short sides. The large panel conserved in the Louvre is typical of Roman civic art and depicts a scene which one would only find at Rome in this period: the census. The other three panels depict a mythological theme in a Hellenistic style: the marriage of Neptune and Amphitrite. Given the difference in style, subject and material, it is thought that the two friezes are not contemporary.[6] The mythological frieze seems to have been executed earlier, covering the three visible sides of the base, which would originally have been connected to the back wall of the cella. Some years later, the base would have been shifted away from the wall, freeing the fourth side for the panel depicting the census.[3][7]

Historic scene

[edit]The historic panel of the base, 5.65 metres long, 0.80 metres high and 0.015 metres thick, is a bas relief of Parian marble, depicting the different stages in a census of the Roman citizen body.[3] The relief, which is one of the first examples of the continuous narrative style,[m 3] is read from left to right and can be divided into three scenes: the recording of the Roman citizens in the register of the censor, the purification of the army before an altar dedicated to Mars and the levy of the soldiers.

First scene

[edit]At the very left of the bas-relief, an official involved in the census (the iurator or "oath taker") records the identity and the property holdings of a man standing before him, holding wax tablets in one hand and stretching out the other, in the gesture of the oath (professio). His statements are recorded in a codex, made up of two wooden tabulae, which the iurator has on his knees. Six more of these codices can be seen stacked at his feet.[m 4] The identity of this man is not absolutely certain, his identification as the iurator is challenged by a detail: he appears to be wearing calcei, special shoes reserved for individuals of Senatorial rank. So he might even be one of the two censors.[6]

This scene marks the beginning of the Roman census, the period when all Roman citizens were recorded. Based on each individual's wealth, the censor, the Roman magistrate here shown to the right of the citizen performing the professio, determined who would sit in the senate and who would serve in the military, which the Romans considered an honour. The censor is depicted with one hand on the shoulder of a fourth person who wears a toga. By this gesture (the manumissio), the censor accepts his declaration and renders his judgement (the discriptio), which concluded the process of assigning the individual to a class. The citizen points to an infantryman with his hand, indicating to him the centuria to which he belongs.[m 5] The scene might depict the censorate of Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus and L. Caecilius Metellus in 115 BC.

Second scene

[edit]

A religious scene follows, the ceremony of the lustrum, which legitimated the census and is presided over by one of the two censors, who touches the altar of Mars with his right hand. Mars is represented in full armour to the left of the altar. At right, three sacrificial victims are led up, the bull, the ram and the pig (the suovetaurilia) which were to be sacrificed in honour of the god in order to secure good fortune for the departure of the troops. The censor is helped during the ceremony by young assistants (camilla), one in the process of pouring the lustral water. Behind Mars, two musicians accompany the sacrifice, one playing the lyre and the other the tibia. The same to accompany the camillus who stands behind the altar and sings the precatio (prayer).[m 6] The second censor advances behind the victims, holding a standard (vexillum).[3]

Third scene

[edit]Finally, at the far right of the bas relief there are two infantrymen and a horseman (eques) with his horse. Along with the other two infantrymen depicted in the first and second scenes, the scene recalls the existence of four classes of mobilisable infantry (pedites) and a class of cavalry formed from the aristocracy.[3]

Mythological scene

[edit]The panels bearing the mythological scene, a marine thiasos of late Hellenistic style, are made of a different marble derived from Asia Minor.[7][3] They are conserved at the Munich Glyptothek. The reliefs probably depict the marriage of Neptune and Amphitrite.

At the centre of the scene, Neptune and Amphitrite are seated in a chariot drawn by two Tritons who dance to music. They are accompanied by a multitude of fantastic creatures, Tritons and Nereides who form a retinue for the wedding couple. At the left, a Nereid riding on a sea-bull carries a present. To her right, the mother of Amphitrite, Doris, advances towards the couple, mounted on a sea-horse and holding wedding torches in each hand to light the procession's way.[m 7] To her right is an Eros, a creature associated with Venus. Behind the wedding couple, a Nereid, accompanied by two more Erotes and riding a hippocamp, carries another present.

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The armour of the soldiers and horseman permits the scene to be dated to the second century BC (Coarelli (1968) and Stilp (2001))

- ^ The first appears on the column erected by the consul Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus in honour of his victory at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC

- ^ The context of the reliefs, their function and their date are not known with precision; numerous contradictory hypotheses have been produced on this subject.

- ^ The identity of the sculptor behind the statuary group is debated; the work is sometimes attributed to Scopas "the Elder" and sometimes to Scopas "the Younger" (Scopas Minor), a second century sculptor of the same name, and sometimes to neither sculptor without any other name being suggested. Only the Greek origin of sculptor seems to have consensus.

References

[edit]Modern sources :

- ^ From the Temple of Fortuna Primigenia in Praeneste (Palestrina), now in the Museo Pio-Clementino in the Vatican Museums, see: D.B. Saddington (2011) [2007]. "the Evolution of the Roman Imperial Fleets," in Paul Erdkamp (ed), A Companion to the Roman Army, 201-217. Malden, Oxford, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2153-8. Plate 12.2 on p. 204.

- ^ Coarelli, Filippo (1987), I Santuari del Lazio in età repubblicana. NIS, Rome, pp 35-84.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cels Saint-Hilaire 2011.

- ^ Coarelli 2007, p. 267.

- ^ a b Coarelli 1968.

- ^ a b c Stilp 2001.

- ^ a b c De Chaisemartin 2003.

Other modern sources :

- ^ Bas-relief de Domitius Ahenobarbus au Louvre sur la base Atlas.

- ^ M. Crawford, Roman Republic Coinage, Cambridge, 1974, p. 525

- ^ André Piganiol, Ara Martis dans Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire, Vol. 51, 1934, p. 29

- ^ Ségolène Demougin, La mémoire perdue : à la recherche des archives oubliées, publiques et privées, de la Rome antique, Publications de la Sorbonne, 1994, p. 132

- ^ Elisabeth Deniaux, Rome, de la Cité-Etat à l'Empire : institutions et vie politique, IIème-Ier siècle av. J.-C., Hachette Éducation Technique, 2001

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum, Thesaurus Cultus Et Rituum Antiquorum, Getty Publications, 2004, p. 407

- ^ Albert Grenier, Le Génie romain dans la religion, la pensée, l'art, Albin Michel, 1969, p. 278

Ancient sources :

- ^ a b Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 36.26

Bibliography

[edit]General Works

[edit]- Cels Saint-Hilaire, Janine (2011). La République romaine: 133-44 av. J.-C (in French). Armand Colin.

- De Chaisemartin, Nathalie (2003). Rome - Paysage urbain et idéologie: Des Scipions à Hadrien (IIe s. av. J.-C.-IIe s. ap. J.-C.) (in French). Armand Colin.

- Coarelli, Filippo (2007). Rome and environs: an archaeological guide. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07961-8.

Analysis of the reliefs

[edit]- Stilp, Florian (2001). Mariage et Suovetaurilia: étude sur le soi-disant " Autel de Domitius Ahenobarbus " (in French). Rome: Giorgio Bretschneider.

- Coarelli, Filippo (1968). "L'" Ara di Domizio Enobarbo " e la cultura artistica in Roma nel II secolo a.C.". Dialoghi di Archeologia (in Italian). 3: 302–368.

- Torelli, Mario (1992). Typology and Structure of Roman Historical Reliefs. University of Michigan Press. pp. 5–16.