Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture

Entrance to the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture | |

| Latin: Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture Institut royal de la culture amazighe | |

| Established | 2001 |

|---|---|

| President | Ahmed Boukouss |

| Secretary General | M. E. H. El Moujahid |

| Address | Alal Fasi Street PO Box 2055 Hay Riad |

| Location | , |

| Website | www.ircam.ma |

The Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (French: Institut royal de la culture amazighe (IRCAM); Standard Moroccan Tamazight: ⴰⵙⵉⵏⴰⴳ ⴰⴳⵍⴷⴰⵏ ⵏ ⵜⵓⵙⵙⵏⴰ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵜ, romanized: Asinag Ageldan n Tussna Tamazight (SGSM); Arabic: المعهد الملكي للثقافة الأمازيغية, romanized: al-Ma‘had al-Malikī lith-Thaqāfah al-Amāzīghīyah) is an academic institute of the Moroccan government in charge with the promotion of the Berber languages and culture, and of the development of Standard Moroccan Amazigh and its instruction in Morocco's public schools.[1][2]

The institute is located in the Moroccan capital of Rabat. It was officially founded on October 17, 2001, under a royal decree of King Mohammed VI, and was run by Amazigh scholars and activists.[1][2][3] The institute had legal and financial independence from the executive branch of government, but its recommendations about the education of the Berber languages in Moroccan public schools are not legally binding to the government.

After nineteen years of existence the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture ceased to exist as an independent institution in February 2020.[4] It continues to function as a division of National Council for Amazigh Languages and Culture.[5]

Role

[edit]The institute offers advice to the Moroccan king and government about the measures that would help develop the Berber language and culture, especially within the educational system.

IRCAM published numerous books on various subjects, such as history, culture, geography, including Amazigh language textbooks, dictionaries and translations. One of the institute's key activities was issuing of the Asīnāg Journal presenting articles, reviews and, what in general constitutes international dialogue on the Amazigh cause.[4]

Linguistic policies advocated by scholars of IRCAM aimed at unifying the whole Moroccan Amazigh community through the creation of a national linguistic standard, which was to function alongside the spoken varieties of Amazigh.[4]

Responsibilities

[edit]- Maintain and develop Standard Moroccan Amazigh.[1]

- Work on the implementation of policies adopted by the king on the subject.

- Help include the Berber language in the Moroccan educational system and ensure its presence in the social and cultural fields and in national, regional and local media.

- Reinforce the status of the Berber culture in the media and society.

- Work with other national institutions and organizations, especially with the ministry of education.

- Act as a reference in the domain of academic Berber studies and research, regionally and internationally, especially in North Africa.

Asinag

[edit]Asinag was a scientific journal published by the institute. Its chief editor was Ahmed Boukouss, IRCAM's president. Among its Scientific Board members there were scholars affiliated with Moroccan, Algerian and even American universities as well as independent scholars and employees of the Moroccan Ministry of Culture. Fourteen issues of the journal have been published. The predominant subject of Asinag was the Amazigh language – its grammar, history, education and functioning in modern Moroccan society.[4]

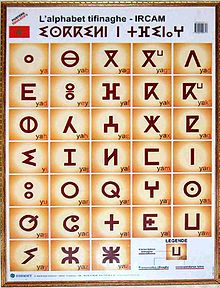

Tifinagh

[edit]

The institute has played a pioneering role in the adoption of Tifinagh for the transcription of Berber languages in Morocco.

The adopted transcription system is an alphabet, as opposed to the original Tifinagh maintained by the Tuaregs which is an abjad. It is made up of 33 characters and is largely inspired by the neo-Tifinagh developed in the 1970s by Kabyle militants.

See also

[edit]References and notes

[edit]Much of the content of this article comes from the equivalent Arabic-language Wikipedia article, accessed October 7, 2006.

- ^ a b c Crawford, David L. (2005). "Royal Interest in Local Culture: Amazigh Identity and the Moroccan State". Nationalism and minority identities in Islamic societies. Maya Shatzmiller. Montreal [Que.]: McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-7735-7254-6. OCLC 191819018.

- ^ a b Wyrtzen, Jonathan (2013). "National resistance, amazighité, and (re)-imagining the nation in Morocco". Revisiting the colonial past in Morocco. Driss Maghraoui. London: Routledge. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-415-63847-0. OCLC 793224528.

- ^ Soulaimani, Dris (2016-01-02). "Writing and rewriting Amazigh/Berber identity: Orthographies and language ideologies". Writing Systems Research. 8 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/17586801.2015.1023176. ISSN 1758-6801. S2CID 144700140.

- ^ a b c d Guzik, Mateusz; Krasnopolski, Maciej; Nabulssi, Zuzanna. "The Forefront of Revitalization. Nineteen Years of the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (IRCAM)" (PDF). Oriental Review. 1 (273): 55–68. doi:10.33896/POrient.2020.1.4 (inactive 31 January 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - ^ "Moroccan Parliament Votes to End the Existence of Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture". Amazigh World News. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in French)

- JurisPedia