Fred Shuttlesworth

Fred Shuttlesworth | |

|---|---|

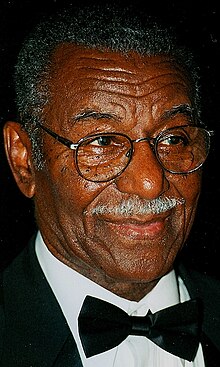

Shuttlesworth in 2002 | |

| 5th President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference | |

| In office August – November 2004 | |

| Preceded by | Martin Luther King III |

| Succeeded by | Charles Steele Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Freddie Lee Robinson March 18, 1922 Mount Meigs, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | October 5, 2011 (aged 89) Birmingham, Alabama, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Hill Cemetery Birmingham, Alabama |

| Known for | Civil Rights Movement |

| Affiliations | Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) |

| Television | Eyes on the Prize (1987) Freedom Riders (2010) |

Freddie Lee Shuttlesworth (born Freddie Lee Robinson, March 18, 1922 – October 5, 2011) was an American civil rights activist who led the fight against segregation and other forms of racism as a minister in Birmingham, Alabama. He was a co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, initiated and was instrumental in the 1963 Birmingham Campaign, and continued to work against racism and for alleviation of the problems of the homeless in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he took up a pastorate in 1961.[1] He returned to Birmingham after his retirement in 2007. He worked with Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights movement, though the two men often disagreed on tactics and approaches.

The Birmingham–Shuttlesworth International Airport was named in his honor in 2008.

The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute Fred L. Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award is bestowed annually in his name.

Early life

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

Born to an African American family in Mount Meigs, Alabama on March 18, 1922,[2] Shuttlesworth became pastor of the Bethel Baptist Church in Birmingham in 1953 and was Membership Chairman of the Alabama state chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1956, when the State of Alabama formally outlawed it from operating within the state. In May 1956, Shuttlesworth and Ed Gardner established the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights to take up the work formerly done by the NAACP.

The ACMHR raised almost all of its funds from local sources at mass meetings. It used both litigation and direct action to pursue its goals. When the authorities ignored the ACMHR's demand that the City hire black police officers, the organization sued. Similarly, when the United States Supreme Court ruled in December 1956 that bus segregation in Montgomery, Alabama, was unconstitutional, Shuttlesworth announced that the ACMHR would challenge segregation laws in Birmingham on December 26, 1956.

On December 25, 1956, an attempt was made on Shuttlesworth's life by placing sixteen sticks of dynamite under his bedroom window. He escaped unhurt although his house was heavily damaged. A police officer, who also belonged to the Ku Klux Klan, told Shuttlesworth as he came out of his home, "If I were you I'd get out of town as quick as I could". Shuttlesworth told him to tell the Klan that he was not leaving and "I wasn't raised to run."

Education

[edit]Fred Shuttlesworth attended Rosedale High School from which he graduated as the valedictorian.[3] Shuttlesworth studied at Selma University, earning his B.A. in 1951, and later earned his B.S. from Alabama State University. Shuttlesworth got his license as a country preacher when he was changing from a Methodist to a Baptist Christian.[4]

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

[edit]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 1957, Shuttlesworth, along with Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy from Montgomery, Joseph Lowery from Mobile, Alabama, T. J. Jemison from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Charles Kenzie Steele from Tallahassee, Florida, A. L. Davis from New Orleans, Louisiana, Bayard Rustin and Ella Baker founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The SCLC adopted a motto to underscore its commitment to nonviolence: "Not one hair of one head of one person should be harmed."

Shuttlesworth embraced that philosophy, even though his own personality was combative, headstrong and sometimes blunt-spoken to the point that he frequently antagonized his colleagues in the Civil Rights Movement as well as his opponents. He was not shy in asking King to take a more active role in leading the fight against segregation and warning that history would not look kindly on those who gave "flowery speeches" but did not act on them. He alienated some members of his congregation by devoting as much time as he did to the movement at the expense of weddings, funerals, and other ordinary church functions.

As a result, in 1961, Shuttlesworth moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, to take up the pastorage of the Revelation Baptist Church. He remained intensely involved in the Birmingham campaign after moving to Cincinnati, and frequently returned to help lead actions.

Shuttlesworth was apparently personally fearless, even though he was aware of the risks he ran. Other committed activists were scared off or mystified by his willingness to accept the risk of death. Shuttlesworth himself vowed to "kill segregation or be killed by it".[1]

Murder attempts

[edit]When Shuttlesworth and his wife Ruby attempted to enroll their children in John Herbert Phillips High School,[5] a previously all-white public school in Birmingham in the summer of 1957,[6] a mob of Klansmen attacked them, with the police nowhere to be seen. The mob beat Shuttlesworth with "chains, baseball bats and brass knuckles, and his wife was stabbed in the hips".[4][5] His assailants included Bobby Frank Cherry, who six years later was involved in the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing.[7] Shuttlesworth drove himself and his wife to the hospital, where he told his children to "always forgive".[citation needed]

In 1958, Shuttlesworth survived another attempt on his life. A church member standing guard saw a bomb that had been placed beside the church and quickly moved it to the street before it went off.[1]

Freedom Rides

[edit]Shuttlesworth participated in the sit-ins against segregated lunch counters in 1960 and took part in the organization and completion of the Freedom Rides in 1961.

Shuttlesworth originally warned that Alabama was extremely volatile when he was consulted before the Freedom Rides began. Shuttlesworth noted that he respected the courage of the activists proposing the Rides but that he felt other actions could be taken to accelerate the Civil Rights Movement that would be less dangerous.[8] However, the planners of the Rides were undeterred and decided to continue preparing.

After it became certain that the Freedom Rides were to be carried out, Shuttlesworth worked with the Congress of Racial Equality (C.O.R.E.) to organize the Rides[9] and became engaged with ensuring the success of the rides, especially during their stint in Alabama.[10] Shuttlesworth mobilized some of his fellow clergy to assist the rides. After the Riders were badly beaten and nearly killed in Birmingham and Anniston during the Rides, he sent deacons to pick up the Riders from a hospital in Anniston. He himself had been brutalized earlier in the day and had faced down the threat of being thrown out of the hospital by the hospital superintendent.[11] Shuttlesworth took in the Freedom Riders at the Bethel Baptist Church, allowing them to recuperate after the violence that had occurred earlier in the day.[12]

The violence in Anniston and Birmingham almost led to a quick end to the Freedom Rides. However, the actions of supporters like Shuttlesworth gave James Farmer, the leader of C.O.R.E., which had originally organized the Freedom Rides, and other activists the courage to press forward.[13] After the violence that occurred in Alabama but before the Freedom Riders could move on, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy gave Shuttlesworth his personal phone number in case the Freedom Riders needed federal support.[14]

When Shuttlesworth prepared the Riders to leave Birmingham and they reached the Greyhound Terminal, the Riders found themselves stranded as no bus driver was willing to drive the controversial group into Mississippi.[14] Shuttlesworth stuck with the Riders[15] and called Kennedy.[14] Prompted by Shuttlesworth, Kennedy tried to find a replacement bus driver; his efforts eventually proved unsuccessful. The Riders then decided to take a plane to New Orleans (where they had planned on finishing the Rides) and were assisted by Shuttlesworth in getting to the airport and onto the plane.[16]

Shuttlesworth's commitment to the Freedom Rides was highlighted by Diane Nash, a student activist in the Nashville Student Movement and a major organizer of the later waves of Rides. Nash noted,

Fred was practically a legend. I think it was important – for me, definitely, and for a city of people who were carrying on a movement – for there to be somebody that really represented strength, and that's certainly what Fred did. He would not back down, and you could count on it. He would not sell out, [and] you could count on that.[1]

The students involved in the Rides appreciated Shuttlesworth's commitment to the principles of the Freedom Rides – ending the segregationist laws of the Jim Crow South. Shuttlesworth's fervent passion for equality made him a role model to many of the Riders.[1]

Project C

[edit]Shuttlesworth invited SCLC and King to come to Birmingham in 1963 to lead the campaign to desegregate it through mass demonstrations–what Shuttlesworth called "Project C", the "C" standing for "confrontation". While Shuttlesworth was willing to negotiate with political and business leaders for peaceful abandonment of segregation, he believed, with good reason, that they would not take any steps that they were not forced to take. He suspected their promises could not be trusted until they acted on them. One of the 1963 demonstrations he led resulted in Shuttlesworth's being convicted of parading without a permit from the City Commission. On appeals the case reached the US Supreme Court. In its 1969 decision of Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, the Supreme Court reversed Shuttlesworth's conviction, determining that circumstances indicated that the parade permit was denied not to control traffic, as the state contended, but to censor ideas.

In 1963, Shuttlesworth was set on provoking a crisis that would force the authorities and business leaders to recalculate the cost of segregation. This occurred when James Bevel initiated and organized the young students of the city to stand up for their rights.[17] This plan was helped immeasurably by Eugene "Bull" Connor, the Commissioner of Public Safety and the most powerful public official in Birmingham, who used Klan groups to heighten violence against blacks in the city. Even as the business class was beginning to see the end of segregation, Connor was determined to maintain it. While Connor's direct police tactics intimidated black citizens of Birmingham, they also created a split between Connor and the business leaders. They resented both the damage Connor was doing to Birmingham's image around the world and his high-handed attitude toward them.

Similarly, while Connor may have benefited politically in the short run from Shuttlesworth's and Bevel's determined provocations, they also fit into Shuttleworth's long-term plans. The televised images of Connor's directing handlers of police dogs to attack young unarmed demonstrators and firefighters using hoses to knock down children had a profound effect on American citizens' view of the civil rights struggle, and helped lead to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Shuttlesworth's activities were not limited to Birmingham. In 1964, he traveled to St. Augustine, Florida (which he often cited as the place where the civil rights struggle met with the most violent resistance), taking part in marches and widely publicized beach wade-ins.

In 1965, he was active in the Selma Voting Rights Movement, and its march from Selma to Montgomery which led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Shuttlesworth thus played a role in the efforts that led to the passage of the two great legislative accomplishments of the Civil Rights Movement. In later years he took part in commemorative activities in Selma at the time of the anniversary of the famous march. And he returned to St. Augustine in 2004 to take part in a celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the St. Augustine movement there.[1][18]

1966–2006: After the Voting Rights Act

[edit]Shuttlesworth organized the Greater New Light Baptist Church in 1966.

In 1978, Shuttlesworth was portrayed by Roger Robinson in the television miniseries King.

Shuttlesworth founded the "Shuttlesworth Housing Foundation" in 1988 to assist families who might otherwise be unable to buy their own homes.

In 1998, Shuttlesworth became an early signer and supporter of the Birmingham Pledge, a grassroots community committed to combating racism and prejudice. It has since then been used for programs in all fifty states and in more than twenty countries.[19]

In 1998, South Crescent Avenue in Cincinnati was renamed in his honor.[20]

On January 8, 2001, he was presented with the Presidential Citizens Medal by President Bill Clinton. Named president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in August 2004, he resigned later in the year, complaining that "deceit, mistrust and a lack of spiritual discipline and truth have eaten at the core of this once-hallowed organization".

In 2004, Shuttlesworth received the Award for Greatest Public Service Benefiting the Disadvantaged, an award is given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[21]

During the 2004 election that overturned a city charter provision that prohibited Cincinnati's City Council from adopting any gay rights ordinance,[22] Shuttlesworth voiced advertisements urging voters to reject the repeal, saying "The thing that I disagree with is when gay people ... equate civil rights, what we did in the '50s and '60s, with special rights ... I think what they propose is special rights. Sexual rights is not the same as civil rights and human rights."[23]

Family

[edit]

Although he was born Freddie Lee Robinson, Shuttlesworth took the name of his stepfather, William N. Shuttlesworth.[24] His stepfather, William N. Shuttlesworth, worked as a coal miner and a bootlegger.[25]

Fred's mother Alberta died in 1995 at the age of 95.[4]

Shuttlesworth was married to Ruby Keeler Shuttlesworth, with whom he had four children: Patricia Shuttlesworth Massengill, Ruby Shuttlesworth Bester, Fred L. Shuttlesworth Jr., and Carolyn Shuttlesworth. The Shuttleworths divorced in 1970, and Ruby died the following year.[26]

After retirement

[edit]Prompted by the removal of a non-cancerous brain tumor in August of the previous year, he gave his final sermon in front of 300 people at the Greater New Light Baptist Church on March 19, 2006—the weekend of his 84th birthday. He and his second wife, Sephira, moved to downtown Birmingham where he was receiving medical treatment.

On July 16, 2008, the Birmingham, Alabama, Airport Authority approved changing the name of the Birmingham's airport in honor of Shuttlesworth. On October 27, 2008, the airport was officially changed to Birmingham–Shuttlesworth International Airport.

On October 5, 2011, Shuttlesworth died at the age of 89 in Birmingham, Alabama. The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute announced that it intended to include Shuttlesworth's burial site on the Civil Rights History Trail.[27][28] By order of Alabama governor Robert Bentley, flags on state government buildings were to be lowered to half-staff until Shuttlesworth's interment.[29]

He is buried in the Oak Hill Cemetery in Birmingham.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Manis, Andrew M (1999). A Fire You Can't Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham's Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0968-3.

- ^ Houck, Davis W.; Dixon, David E., eds. (2006). Rhetoric, Religion and the Civil Rights Movement 1954-1965. Waco: Baylor University Press. p. 250. ISBN 1-932792-54-6. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ Albert, Melissa. "Fred Shuttlesworth Americans Minister And Civil Rights Activist". Encyclopedia Britannica, March 14, 2019.

- ^ a b c The JBHE Foundation. "Fred Shuttleworth: The Man Who Pushed Martin Luther King Jr. Into Greatness". Fred Shuttleworth: He Pushed Martin Luther King Jr. Into Greatness, October 15, 2001, pp. 61–64. The JBHE Foundation, doi:10.2307/2678916.

- ^ a b CBS, director. The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom Civil Rights Activist Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth on Bombings and Beatings in 1950s Birmingham. Library of Congress/The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom, CBS News, May 18, 1961, www.loc.gov/exhibits/civil-rights-act/multimedia/fred-shuttlesworth.html.

- ^ CBS, director J. Mills Thornton III. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. Vol. 733, The University of Alabama Press, 2002.

- ^ Bragg, Rick (May 23, 2002). "38 Years Later, Last of Suspects Is Convicted in Church Bombing". The New York Times.

- ^ Arsenault, Raymond (2006). Freedom riders: 1961 and the struggle for racial justice. Oxford UP. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-19-513674-6.

- ^ African American Registry. "Fred Shuttlesworth, Minister and Leader!" "Fred Shuttlesworth, minister and leader! | African American Registry". Archived from the original on March 23, 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2011..

- ^ "FindArticles.com | CBSi". findarticles.com. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ Arsenault, Raymond (2006). Freedom riders: 1961 and the struggle for racial justice. Oxford UP. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-19-513674-6.

- ^ Arsenault, Raymond (2006). Freedom riders: 1961 and the struggle for racial justice. Oxford UP. pp. 159–62. ISBN 978-0-19-513674-6.

- ^ Arsenault, Raymond (2006). Freedom riders: 1961 and the struggle for racial justice. Oxford UP. pp. 166–9. ISBN 978-0-19-513674-6.

- ^ a b c Arsenault, Raymond (2006). Freedom riders: 1961 and the struggle for racial justice. Oxford UP. pp. 170–1. ISBN 978-0-19-513674-6.

- ^ The Birmingham News (February 26, 2006). "The Road to Change". "Al.com: Unseen. Unforgotten". Archived from the original on December 27, 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2011..

- ^ Arsenault, Raymond (2006). Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. Oxford University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-19-513674-6.

- ^ "James L. Bevel The Strategist of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement" by Randy Kryn, a paper in 1989 book We Shall Overcome, Volume II, Carlson Publishing Company

- ^ McWhorter, Diane (2001). Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama, the Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-1772-1.

- ^ "Birmingham Pledge". Encyclopedia of Alabama. May 12, 2011. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ "Cincinnati street's name honors a King associate". November 10, 1998.

- ^ "O'Connor wins top honor at Jefferson Awards fete". AP. June 24, 2004.

- ^ Aldridge, Kevin (November 3, 2004). "City voters repeal amendment on gay rights". The Cincinnati Enquirer.

- ^ Johnston, John; Alltucker, Ken (October 17, 2004). "Coming to terms with gay issues: Region leans toward tolerance, not acceptance". The Cincinnati Enquirer.

- ^ Thornton, J. Mills III (2002). Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 189. ISBN 0-8173-1170-X. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ J. Mills Thornton III. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. Vol. 733, The University of Alabama Press, 2002.

- ^ Schudel, Matt (October 6, 2011). "Fred L. Shuttlesworth, courageous civil rights fighter, dies at 89". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ Gates, Verna (October 5, 2011). "Birmingham civil rights leader Fred Shuttlesworth dies". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Washington, Dennis. "Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth passes away". MyFoxAL.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Stewart, Sherrel (October 6, 2011). "Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley orders flags on state buildings at half staff for Rev. Shuttlesworth". al.com. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Garrison, Greg (October 24, 2011). "Shuttlesworth buried at Birmingham's Oak Hill after final tributes". AL.com.

Bibliography

[edit]- Andrew Manis. (1999) A Fire You Can't Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham's Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0968-3

- Branch, Taylor (1988) Parting The Waters; America In The King Years 1954–63. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-46097-8

- Manis, Andrew M. (Summer–Fall 2000) "Birmingham's Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth: unsung hero of the civil rights movement".. Baptist History and Heritage. – accessed January 17, 2007

- *McWhorter, Diane (2001). Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama, the Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-1772-1

- Nunnelley, William (1991). Bull Connor. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-585-32316-X

- White, Marjorie Longenecker (1998) A Walk to Freedom: The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society. ISBN 0-943994-24-1

- White, Marjorie, Manis, Andrew, eds. (2000) Birmingham Revolutionaries: The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Mercer University Press. ISBN 0-86554-709-2

- Curnutte, Mark (January 20, 1997) "In the Name of Civil Rights: The Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth carries on a 40-year fight as the movement's 'battlefield general'." Cincinnati Enquirer – accessed January 20, 2007.

- "The Champion" (November 26, 1965) Time.

- Walton, Val (February 19, 2008) "Rev. Shuttlesworth to return to Birmingham for post-stroke therapy". Birmingham News

- Garrison, Greg (June 29, 2008) "Legacy, history of civil rights icon Fred Shuttlesworth". Birmingham News

- The White House – Office of the Press Secretary

External links

[edit]- Fred Shuttlesworth from the Encyclopedia of Alabama

- Fred Shuttleswoth's oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Fred Shuttleswoth in The Road to Equality roundtable discussion on CETconnect

- African-American Baptist ministers

- Baptist ministers from the United States

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- People from Montgomery County, Alabama

- Activists from Birmingham, Alabama

- African-American activists

- Freedom Riders

- Presidential Citizens Medal recipients

- 1922 births

- 2011 deaths

- American nonviolence advocates

- Baptists from Alabama

- 21st-century African-American people

- Birmingham campaign