Societal collapse

Societal collapse (also known as civilizational collapse or systems collapse) is the fall of a complex human society characterized by the loss of cultural identity and of social complexity as an adaptive system, the downfall of government, and the rise of violence.[1] Possible causes of a societal collapse include natural catastrophe, war, pestilence, famine, economic collapse, population decline or overshoot, mass migration, incompetent leaders, and sabotage by rival civilizations.[2] A collapsed society may revert to a more primitive state, be absorbed into a stronger society, or completely disappear.

Virtually all civilizations have suffered such a fate, regardless of their size or complexity. Most never recovered, such as the Western and Eastern Roman Empires, the Maya civilization, and the Easter Island civilization.[1] However, some of them later revived and transformed, such as China, Greece, and Egypt.

Anthropologists, historians, and sociologists have proposed a variety of explanations for the collapse of civilizations involving causative factors such as environmental degradation, depletion of resources, costs of rising complexity, invasion, disease, decay of social cohesion, growing inequality, extractive institutions, long-term decline of cognitive abilities, loss of creativity, and misfortune.[1][3][4] However, complete extinction of a culture is not inevitable, and in some cases, the new societies that arise from the ashes of the old one are evidently its offspring, despite a dramatic reduction in sophistication.[3] Moreover, the influence of a collapsed society, such as the Western Roman Empire, may linger on long after its death.[5]

The study of societal collapse, collapsology, is a topic for specialists of history, anthropology, sociology, and political science. More recently, they are joined by experts in cliodynamics and study of complex systems.[6][3]

Concept

[edit]Joseph Tainter frames societal collapse in The Collapse of Complex Societies (1988), a seminal and founding work of the academic discipline on societal collapse.[7] He elaborates that 'collapse' is a "broad term," but in the sense of societal collapse, he views it as "a political process."[8] He further narrows societal collapse as a rapid process (within "few decades") of "substantial loss of sociopolitical structure," giving the fall of the Western Roman Empire as "the most widely known instance of collapse" in the Western world.[8]

Others, particularly in response to the popular Collapse (2005) by Jared Diamond[9] and more recently, have argued that societies discussed as cases of collapse are better understood through resilience and societal transformation,[10] or "reorganization", especially if collapse is understood as a "complete end" of political systems, which according to Shmuel Eisenstadt has not taken place at any point.[11] Eisenstadt also points out that a clear differentiation between total or partial decline and "possibilities of regeneration" is crucial for the preventive purpose of the study of societal collapse.[11] This frame of reference often rejects the term collapse and critiques the notion that cultures simply vanish when the political structures that organize labor for large archaeologically prominent projects do. For example, while the Ancient Maya are often touted as a prime example of collapse, in reality this reorganization was simply the result of the removal of the political system of Divine Kingship largely in the eastern lowlands as many cities in the western highlands of Mesoamerica maintained this system of divine kingship into the 16th century. The Maya continue to maintain cultural and linguistic continuity into the present day.

Societal longevity

[edit]The social scientist Luke Kemp analyzed dozens of civilizations, which he defined as "a society with agriculture, multiple cities, military dominance in its geographical region and a continuous political structure," from 3000 BC to 600 AD and calculated that the average life span of a civilization is close to 340 years.[1] Of them, the most durable were the Kushite Kingdom in Northeast Africa (1,150 years), the Aksumite Empire in East Africa (1,100 years), and the Vedic civilization in South Asia and the Olmecs in Mesoamerica (both 1,000 years), and the shortest-lived were the Nanda Empire in India (24) and the Qin dynasty in China (14).[12]

A statistical analysis of empires by complex systems specialist Samuel Arbesman suggests that collapse is generally a random event and does not depend on age. That is analogous to what evolutionary biologists call the Red Queen hypothesis, which asserts that for a species in a harsh ecology, extinction is a persistent possibility.[1]

Contemporary discussions about societal collapse are seeking resilience by suggesting societal transformation.[13]

Causes of collapse

[edit]Because human societies are complex systems, common factors may contribute to their decline that are economical, environmental, demographic, social and cultural, and they may cascade into another and build up to the point that could overwhelm any mechanisms that would otherwise maintain stability. Unexpected and abrupt changes, which experts call nonlinearities, are some of the warning signs.[14] In some cases, a natural disaster (such as a tsunami, earthquake, pandemic, massive fire or climate change) may precipitate a collapse. Other factors such as a Malthusian catastrophe, overpopulation, or resource depletion might be contributory factors of collapse, but studies of past societies seem to suggest that those factors did not cause the collapse alone.[15] Significant inequity and exposed corruption may combine with lack of loyalty to established political institutions and result in an oppressed lower class rising up and seizing power from a smaller wealthy elite in a revolution. The diversity of forms that societies evolve corresponds to diversity in their failures. Jared Diamond suggests that societies have also collapsed through deforestation, loss of soil fertility, restrictions of trade and/or rising endemic violence.[16]

In the case of the Western Roman Empire, some argued that it did not collapse but merely transformed.[17]

Natural disasters and climate change

[edit]

Archeologists have identified signs of a megadrought which lasted for a millennium between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago in Africa and Asia. The drying of the Green Sahara not only turned it into a desert but also disrupted the monsoon seasons in South and Southeast Asia and caused flooding in East Asia, which prevented successful harvests and the development of complex culture. It coincided with and may have caused the decline and the fall of the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley Civilization.[19] The dramatic shift in climate is known as the 4.2-kiloyear event.[20]

The highly advanced Indus Valley Civilization took root around 3000 BC in what is now northwestern India and Pakistan and collapsed around 1700 BC. Since the Indus script has yet to be deciphered, the causes of its de-urbanization[18] remain a mystery, but there is some evidence pointing to natural disasters.[21] Signs of a gradual decline began to emerge in 1900 BC, and two centuries later, most of the cities had been abandoned. Archeological evidence suggests an increase in interpersonal violence and in infectious diseases like leprosy and tuberculosis.[22][23] Historians and archeologists believe that severe and long-lasting drought and a decline in trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia caused the collapse.[24] Evidence for earthquakes has also been discovered. Sea level changes are also found at two possible seaport sites along the Makran coast which are now inland. Earthquakes may have contributed to decline of several sites by direct shaking damage or by changes in sea level or in water supply.[25][26][27]

Volcanic eruptions can abruptly influence the climate. During a large eruption, sulfur dioxide (SO2) is expelled into the stratosphere, where it could stay for years and gradually get oxidized into sulfate aerosols. Being highly reflective, sulfate aerosols reduce the incident sunlight and cool the Earth's surface. By drilling into glaciers and ice sheets, scientists can access the archives of the history of atmospheric composition. A team of multidisciplinary researchers led by Joseph McConnell of the Desert Research Institute in Reno, Nevada deduced that a volcanic eruption occurred in 43 BC, a year after the assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March (15 March) in 44 BC, which left a power vacuum and led to bloody civil wars. According to historical accounts, it was also a period of poor weather, crop failure, widespread famine, and disease. Analyses of tree rings and cave stalagmites from different parts of the globe provided complementary data. The Northern Hemisphere got drier, but the Southern Hemisphere became wetter. Indeed, the Greek historian Appian recorded that there was a lack of flooding in Egypt, which also faced famine and pestilence. Rome's interest in Egypt as a source of food intensified, and the aforementioned problems and civil unrest weakened Egypt's ability to resist. Egypt came under Roman rule after Cleopatra committed suicide in 30 BC. While it is difficult to say for certain whether Egypt would have become a Roman province if Okmok volcano (in modern-day Alaska) had not erupted, the eruption likely hastened the process.[28]

More generally, recent research pointed to climate change as a key player in the decline and fall of historical societies in China, the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas. In fact, paleoclimatogical temperature reconstruction suggests that historical periods of social unrest, societal collapse, and population crash and significant climate change often occurred simultaneously. A team of researchers from Mainland China and Hong Kong were able to establish a causal connection between climate change and large-scale human crises in pre-industrial times. Short-term crises may be caused by social problems, but climate change was the ultimate cause of major crises, starting with economic depressions.[30] Moreover, since agriculture is highly dependent on climate, any changes to the regional climate from the optimum can induce crop failures.[31]

The Mongol conquests corresponded to a period of cooling in the Northern Hemisphere between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when the Medieval Warm Period was giving way to the Little Ice Age, which caused ecological stress. In Europe, the cooling climate did not directly facilitate the Black Death, but it caused wars, mass migration, and famine, which helped diseases spread.[31]

A more recent example is the General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century in Europe, which was a period of inclement weather, crop failure, economic hardship, extreme intergroup violence, and high mortality because of the Little Ice Age. The Maunder Minimum involved sunspots being exceedingly rare. Episodes of social instability track the cooling with a time lap of up to 15 years, and many developed into armed conflicts, such as the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648),[30] which started as a war of succession to the Bohemian throne. Animosity between Protestants and Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire (in modern-day Germany) added fuel to the fire. Soon, it escalated to a huge conflict that involved all major European powers and devastated much of Germany. When the war had ended, some regions of the empire had seen their populations drop by as much as 70%.[32][note 1] However, not all societies faced crises during this period. Tropical countries with high carrying capacities and trading economies did not suffer much because the changing climate did not induce an economic depression in those places.[30]

Foreign invasions and mass migration

[edit]Between ca. 4000 and 3000 BCE, neolithic populations in western Eurasia declined, probably due to the plague and other viral hemorrhagic fevers.[33] This decline was followed by the Indo-European migrations.[34] Around 3,000 BC, people of the pastoralist Yamnaya culture from the Pontic–Caspian steppe, who had high levels of WSH ancestry, embarked on a massive expansion throughout Eurasia, which is considered to be associated with the dispersal of the Indo-European languages by most contemporary linguists, archaeologists, and geneticists. The expansion of WSHs resulted in the virtual disappearance of the Y-DNA of Early European Farmers (EEFs) from the European gene pool, significantly altering the cultural and genetic landscape of Europe. EEF mtDNA however remained frequent, suggesting admixture between WSH males and EEF females.[35]

In the third century BC, a Eurasian nomadic people, the Xiongnu, began threatening China's frontiers, but by the first century BC, they had been completely expelled. They then turned their attention westward and displaced various other tribes in Eastern and Central Europe, which led to a cascade of events. Attila rose to power as leader of the Huns and initiated a campaign of invasions and looting and went as far as Gaul (modern-day France). Attila's Huns were clashing with the Roman Empire, which had already been divided into two-halves for ease of administration: the Eastern Roman Empire and the Western Roman Empire. Despite managing to stop Attila at the Battle of Chalons in 451 AD, the Romans were unable to prevent Attila from attacking Roman Italy the next year. Northern Italian cities like Milan were ravaged. The Huns never again posed a threat to the Romans after Attila's death, but the rise of the Huns also forced the Germanic peoples out of their territories and made those groups press their way into parts of France, Spain, Italy, and even as far south as North Africa. The city of Rome itself came under attack by the Visigoths in 410 and was plundered by the Vandals in 455.[note 2][36][better source needed] A combination of internal strife, economic weakness, and relentless invasions by the Germanic peoples pushed the Western Roman Empire into terminal decline. The last Western Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was dethroned in 476 by the German Odoacer, who declared himself King of Italy.[37][better source needed]

In the eleventh century AD, North Africa's populous and flourishing civilization collapsed after it had exhausted its resources in internal fighting and suffering devastation from the invasion of the Bedouin tribes of Banu Sulaym and Banu Hilal.[38] Ibn Khaldun noted that all of the lands ravaged by Banu Hilal invaders had become arid desert.[39]

In 1206, a warlord achieved dominance over all Mongols with the title Genghis Khan and began his campaign of territorial expansion. The Mongols' highly flexible and mobile cavalry enabled them to conquer their enemies with efficiency and swiftness.[40][better source needed] In the brutal pillaging that followed Mongol invasions during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the invaders decimated the populations of China, Russia, the Middle East, and Islamic Central Asia. Later Mongol leaders, such as Timur, destroyed many cities, slaughtered thousands of people, and irreparably damaged the ancient irrigation systems of Mesopotamia. The invasions transformed a settled society to a nomadic one.[41] In China, for example, a combination of war, famine, and pestilence during the Mongol conquests halved the population, a decline of around 55 million people.[31] The Mongols also displaced large numbers of people and created power vacuums. The Khmer Empire went into decline and was replaced by the Thais, who were pushed southward by the Mongols. The Vietnamese, who succeeded in defeating the Mongols, also turned their attention to the south and by 1471 began to subjugate the Chams.[42][better source needed] When Vietnam's Later Lê dynasty went into decline in the late 1700s, a bloody civil war erupted between the Trịnh family in the north and the Nguyễn family in the south.[43][note 3] More Cham provinces were seized by the Nguyễn warlords.[44] Finally, Nguyễn Ánh emerged victorious and declared himself Emperor of Vietnam (changing the name from Annam) with the title Gia Long and established the Nguyễn dynasty.[43] The last remaining principality of Champa, Panduranga (modern-day Phan Rang, Vietnam), survived until 1832,[45] when Emperor Minh Mạng (Nguyễn Phúc Đảm) conquered it after centuries of Cham–Vietnamese wars. Vietnam's policy of assimilation involved the forcefeeding of pork to Muslims and beef to Hindus, which fueled resentment. An uprising followed, the first and only war between Vietnam and the jihadists, until it was crushed.[46][47][48]

Famine, economic depression, and internal strife

[edit]Around 1210 BC, the New Kingdom of Egypt shipped large amounts of grain to the disintegrating Hittite Empire. Thus, there had been a food shortage in Anatolia but not the Nile Valley.[49] However, that soon changed. Although Egypt managed to deliver a decisive and final defeat to the Sea Peoples at the Battle of Xois, Egypt itself went into steep decline. The collapse of all other societies in the Eastern Mediterranean disrupted established trade routes and caused widespread economic depression. Government workers became underpaid, which resulted in the first labor strike in recorded history and undermined royal authority.[50] There was also political infighting between different factions of government. Bad harvest from the reduced flooding at the Nile led to a major famine. Food prices rose to eight times their normal values and occasionally even reached twenty-four times. Runaway inflation followed. Attacks by the Libyans and Nubians made things even worse. Throughout the Twentieth Dynasty (~1187–1064 BC), Egypt devolved from a major power in the Mediterranean to a deeply divided and weakened state, which later came to be ruled by the Libyans and the Nubians.[49]

Between 481 BC and 221 BC, the Period of the Warring States in China ended by King Zheng of the Qin dynasty succeeding in defeating six competing factions and thus becoming the first Chinese emperor, titled Qin Shi Huang. A ruthless but efficient ruler, he raised a disciplined and professional army and introduced a significant number of reforms, such as unifying the language and creating a single currency and system of measurement. In addition, he funded dam constructions and began building the first segment of what was to become the Great Wall of China to defend his realm against northern nomads. Nevertheless, internal feuds and rebellions made his empire fall apart after his death in 210 B.C.[51]

In the early fourteenth century AD, Britain suffered repeated rounds of crop failures from unusually heavy rainfall and flooding. Much livestock either starved or drowned. Food prices skyrocketed, and King Edward II attempted to rectify the situation by imposing price controls, but vendors simply refused to sell at such low prices. In any case, the act was abolished by the Lincoln Parliament in 1316. Soon, people from commoners to nobles were finding themselves short of food. Many resorted to begging, crime, and eating animals they otherwise would not eat. People in northern England had to deal with raids from Scotland. There were even reports of cannibalism.

In Continental Europe, things were at least just as bad. The Great Famine of 1315–1317 coincided with the end of the Medieval Warm Period and the start of the Little Ice Age. Some historians suspect that the change in climate was due to Mount Tarawera in New Zealand erupting in 1314.[52] The Great Famine was, however, only one of the calamities striking Europe that century, as the Hundred Years' War and Black Death would soon follow.[52][53] (Also see the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages.) Recent analysis of tree rings complement historical records and show that the summers of 1314–1316 were some of the wettest on record over a period of 700 years.[53]

Disease outbreaks

[edit]

Historically, the dawn of agriculture led to the rise of contagious diseases.[54] Compared to their hunting-gathering counterparts, agrarian societies tended to be sedentary, have higher population densities, be in frequent contact with livestock, and be more exposed to contaminated water supplies and higher concentrations of garbage. Poor sanitation, a lack of medical knowledge, superstitions, and sometimes a combination of disasters exacerbated the problem.[1][54][55] The journalist Michael Rosenwald wrote that "history shows that past pandemics have reshaped societies in profound ways. Hundreds of millions of people have died. Empires have fallen. Governments have cracked. Generations have been annihilated."[56]

From the description of symptoms by the Greek physician Galen, which included coughing, fever, (blackish) diarrhea, swollen throat, and thirst, modern experts identified the probable culprits of the Antonine Plague (165–180 AD) to have been smallpox or measles.[56][57] The disease likely started in China and spread to the West via the Silk Road. Roman troops first contracted the disease in the East before they returned home. Striking a virgin population, the Antonine Plague had dreadful mortality rates; between one third to half of the population, 60 to 70 million people, perished. Roman cities suffered from a combination of overcrowding, poor hygiene, and unhealthy diets. They quickly became epicenters. Soon, the disease reached as far as Gaul and mauled Roman defenses along the Rhine. The ranks of the previously formidable Roman army had to be filled with freed slaves, German mercenaries, criminals, and gladiators. That ultimately failed to prevent the Germanic tribes from crossing the Rhine. On the civilian side, the Antonine Plague created drastic shortages of businessmen, which disrupted trade, and farmers, which led to a food crisis. An economic depression followed and government revenue fell. Some accused Emperor Marcus Aurelius and Co-Emperor Lucius Verus, both of whom victims of the disease, of affronting the gods, but others blamed Christians. However, the Antonine Plague strengthened the position of the monotheistic religion of Christianity in the formerly-polytheistic society, as Christians won public admiration for their good works. Ultimately the Roman army, the Roman cities, the size of the empire and its trade routes, which were required for Roman power and influence to exist, facilitated the spread of the disease. The Antonine Plague is considered by some historians as a useful starting point for understanding the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire. It was followed by the Plague of Cyprian (249–262 AD) and the Plague of Justinian (541-542). Together, they cracked the foundations of the Roman Empire.[57]

In the sixth century AD, while the Western Roman Empire had already succumbed to attacks by the Germanic tribes, the Eastern Roman Empire stood its ground. In fact, a peace treaty with the Persians allowed Emperor Justinian the Great to concentrate on recapturing territories belonging to the Western Empire. His generals, Belisarius and Narses, achieved a number of important victories against the Ostrogoths and the Vandals.[58] However, their hope of keeping the Western Empire was dashed by the arrival of what became known as the Plague of Justinian (541-542). According to the Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea, the epidemic originated in China and Northeastern India and reached the Eastern Roman Empire via trade routes terminating in the Mediterranean. Modern scholarship has deduced that the epidemic was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, the same one that would later bring the Black Death, the single deadliest pandemic in human history, but how many actually died from it remains uncertain. Current estimates put the figure between thirty and fifty million people,[55] a significant portion of the human population at that time.[59] The Plague arguably cemented the fate of Rome.[55]

The epidemic also devastated the Sasanian Empire in Persia. Caliph Abu Bakr seized the opportunity to launch military campaigns that overran the Sassanians and captured Roman-held territories in the Caucasus, the Levant, Egypt, and elsewhere in North Africa. Before the Justinian Plague, the Mediterranean world had been commercially and culturally stable. After the Plague, it fractured into a trio of civilizations battling for power: the Islamic Civilization, the Byzantine Empire, and what later became known as Medieval Europe. With so many people dead, the supply of workers, many of whom were slaves, was critically short. Landowners had no choice but to lend pieces of land to serfs to work the land in exchange for military protection and other privileges. That sowed the seeds of feudalism.[60]

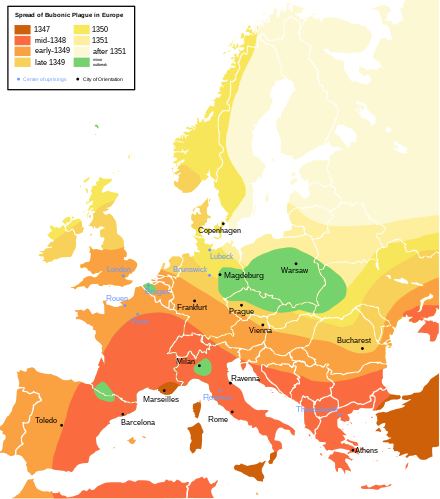

There is evidence that the Mongol expeditions may have spread the bubonic plague across much of Eurasia, which helped to spark the Black Death of the early fourteenth century.[61][62][63][64] The Italian historian Gabriele de’ Mussi wrote that the Mongols catapulted the corpses of those who contracted the plague into Caffa (now Feodossia, Crimea) during the siege of that city and that soldiers who were transported from there brought the plague to Mediterranean ports. However, that account of the origin of the Black Death in Europe remains controversial, though plausible, because of the complex epidemiology of the plague. Modern epidemiologists do not believe that the Black Death had a single source of spreading into Europe. Research into the past on this topic is further complicated by politics and the passage of time. It is difficult to distinguish between natural epidemics and biological warfare, both of which are common throughout human history.[62] Biological weapons are economical because they turn an enemy casualty into a delivery system and so were favored in armed conflicts of the past. Furthermore, more soldiers died of disease than in combat until recently.[note 4][59] In any case, by the 1340s, Black Death killed 200 million people.[55] The widening trade routes in the Late Middle Ages helped the plague spread rapidly.[56] It took the European population more than two centuries to return to its level before the pandemic.[55] Consequently, it destabilized most of society and likely undermined feudalism and the authority of the Church.[65]

With labor in short supply, workers' bargaining power increased dramatically. Various inventions that reduced the cost of labor, saved time, and raised productivity, such as the three-field crop rotation system, the iron plow, the use of manure to fertilize the soil, and the water pumps, were widely adopted. Many former serfs, now free from feudal obligations, relocated to the cities and changed profession to crafts and trades. The more successful ones became the new middle class. Trade flourished as demands for a myriad of consumer goods rose. Society became wealthier and could afford to fund the arts and the sciences.[60]

Encounters between European explorers and Native Americans exposed the latter to a variety of diseases of extraordinary virulence. Having migrated from Northeastern Asia 15,000 years ago, Native Americans had not been introduced to the plethora of contagious diseases that emerged after the rise of agriculture in the Old World. As such, they had immune systems that were ill-equipped to handle the diseases to which their counterparts in Eurasia had become resistant. When the Europeans arrived in the Americas, in short order, the indigenous populations of the Americas found themselves facing smallpox, measles, whooping cough, and the bubonic plague, among others. In tropical areas, malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, river blindness, and others appeared. Most of these tropical diseases were traced to Africa.[66] Smallpox ravaged Mexico in the 1520s and killed 150,000 in Tenochtitlán alone, including the emperor, and Peru in the 1530s, which aided the European conquerors.[67] A combination of Spanish military attacks and evolutionarily novel diseases finished off the Aztec Empire in the sixteenth century.[1][66] It is commonly believed that the death of as much as 90% or 95% of the Native American population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases,[66][68] though new research suggests tuberculosis from seals and sea lions played a significant part.[69]

Similar events took place in Oceania and Madagascar.[66] Smallpox was externally brought to Australia. The first recorded outbreak, in 1789, devastated the Aboriginal population. The extent of the outbreak is disputed, but some sources claim that it killed about 50% of coastal Aboriginal populations on the east coast.[70] There is an ongoing historical debate concerning two rival and irreconcilable theories about how the disease first entered the continent (see History of smallpox). Smallpox continued to be a deadly disease and killed an estimated 300 million people in the twentieth century alone, but a vaccine, the first of any kind, had been available since 1796.[59]

As humans spread around the globe, human societies flourish and become more dependent on trade, and because urbanization means that people leave sparsely-populated rural areas for densely-populated neighborhoods, infectious diseases spread much more easily. Outbreaks are frequent, even in the modern era, but medical advances have been able to alleviate their impacts.[55] In fact, the human population grew tremendously in the twentieth century, as did the population of farm animals, from which diseases could jump to humans, but in the developed world and increasingly also in the developing world, people are less likely to fall victim to infectious diseases than ever before. For instance, the advent of antibiotics, starting with penicillin in 1928, has resulted in the saving of the lives of hundreds of millions of people suffering from bacterial infections. However, there is no guarantee that would continue because bacteria are becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotics, and doctors and public health experts such as former Chief Medical Officer for England Sally Davies have even warned of an incoming "antibiotic apocalypse." The World Health Organization warned in 2019 that the spread of vaccine scepticism has been accompanied by the resurrection of long-conquered diseases like measles. This lead the WHO to name the antivaccination movement one of the world's top 10 public-health threats.[59]

Institutional unemployment

[edit]During the Roman Empire, citizen employment was vastly being replaced by slave labor. Slaves were replacing many of the jobs citizens were doing. Slaves were receiving apprenticeships and education and were even learning to replace the jobs of skilled craftsman.[71]

Since slaves do not pay taxes and were replacing most jobs from citizens, this reduced the revenue the state could accrue from their citizens.

This high level of unemployment also led to high levels of poverty, which reduced demand for businesses relying on slave labor.

As taxes fell, so did government revenue. To compensate for this economic slowdown and mitigate the high levels of poverty, the Roman government implemented a form of welfare called the dole, providing citizens free money and free grain.[72]

Paying for the dole required high levels of government spending, exacerbating the Roman debt and also producing inflation. With slavery replacing most labor, tax revenues also plummeted, further exacerbating the government's debt.

To pay off the enormous debt, the Romans began to devalue the currency and produce more coinage. Eventually, this overwhelmed the Roman Empire and partially contributed to its collapse. [73]

Demographic dynamics

[edit]Several key features of human societal collapse can be related to population dynamics.[74] For example, the native population of Cusco, Peru at the time of the Spanish conquest was stressed by an imbalanced sex ratio.[75]

There is strong evidence that humans also display population cycles.[76] Societies as diverse as those of England and France during the Roman, medieval, and early modern eras, of Egypt during Greco-Roman and Ottoman rule, and of various dynasties in China all showed similar patterns of political instability and violence becoming considerably more common after times of relative peace, prosperity, and sustained population growth. Quantitatively, periods of unrest included many times more events of instability per decade and occurred when the population was declining, rather than increasing. Pre-industrial agrarian societies typically faced instability after one or two centuries of stability. However, a population approaching its carrying capacity alone is not enough to trigger general decline if the people remained united and the ruling class strong. Other factors had to be involved, such as having more aspirants for positions of the elite than the society could realistically support (elite overproduction), which led to social strife, and chronic inflation, which caused incomes to fall and threatened the fiscal health of the state.[77] In particular, an excess in especially young adult male population predictably led to social unrest and violence, as the third and higher-order parity sons had trouble realizing their economic desires and became more open to extreme ideas and actions.[78] Adults in their 20s are especially prone to radicalization.[79] Most historical periods of social unrest lacking in external triggers, such as natural calamities, and most genocides can be readily explained as a result of a built-up youth bulge.[78] As those trends intensified, they jeopardized the social fabric, which facilitated the decline.[77]

Theories

[edit]

Historical theories have evolved from being purely social and ethical, to ideological and ethnocentric, and finally to multidisciplinary studies. They have become much more sophisticated.[49]

Cognitive decline and loss of creativity

[edit]The anthropologist Joseph Tainter theorized that collapsed societies essentially exhausted their own designs and were unable to adapt to natural diminishing returns for what they knew as their method of survival.[80] The philosopher Oswald Spengler argued that a civilization in its "winter" would see a disinclination for abstract thinking.[49] The psychologists David Rand and Jonathan Cohen theorized that people switch between two broad modes of thinking. The first is fast and automatic but rigid, and the second is slow and analytical but more flexible. Rand and Cohen believe that explains why people continue with self-destructive behaviors when logical reasoning would have alerted them of the dangers ahead. People switch from the second to the first mode of thinking after the introduction of an invention that dramatically increases the standards of living. Rand and Cohen pointed to the recent examples of the antibiotic overuse leading to resistant bacteria and failure to save for retirement. Tainter noted that according to behavioral economics, the human decision-making process tends to be more irrational than rational and that as the rate of innovation declines, as measured by the number of inventions relative to the amount of money spent on research and development, it becomes progressively harder for there to be a technological solution to the problem of societal collapse.[5]

Social and environmental dynamics

[edit]

What produces modern sedentary life, unlike nomadic hunter-gatherers, is extraordinary modern economic productivity. Tainter argues that exceptional productivity is actually more the sign of hidden weakness because of a society's dependence on it and its potential to undermine its own basis for success by not being self limiting, as demonstrated in Western culture's ideal of perpetual growth.[80]

As a population grows and technology makes it easier to exploit depleting resources, the environment's diminishing returns are hidden from view. Societal complexity is then potentially threatened if it develops beyond what is actually sustainable, and a disorderly reorganization were to follow. The scissors model of Malthusian collapse, in which the population grows without limit but not resources, is the idea of great opposing environmental forces cutting into each other.

The complete breakdown of economic, cultural, and social institutions with ecological relationships is perhaps the most common feature of collapse. In his book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Jared Diamond proposes five interconnected causes of collapse that may reinforce each other: non-sustainable exploitation of resources, climate changes, diminishing support from friendly societies, hostile neighbors, and inappropriate attitudes for change.[16][81]

Energy return on investment

[edit]Energy has played a crucial role throughout human history. Energy is linked to the birth, growth, and decline of each and every society. Energy surplus is required for the division of labor and the growth of cities. Massive energy surplus is needed for widespread wealth and cultural amenities. Economic prospects fluctuate in tandem with a society's access to cheap and abundant energy.[82]

Political scientist Thomas Homer-Dixon and ecologist Charles Hall proposed an economic model called energy return on investment (EROI), which measures the amount of surplus energy a society gets from using energy to obtain energy.[83][84] Energy shortages drive up prices and as such provide an incentive to explore and extract previously uneconomical sources, which may still be plentiful, but more energy would be required, and the EROI is then not as high as initially thought.[82]

There would be no surplus if EROI approaches 1:1. Hall showed that the real cutoff is well above that and estimated that 3:1 to sustain the essential overhead energy costs of a modern society. The EROI of the most preferred energy source, petroleum, has fallen in the past century from 100:1 to the range of 10:1 with clear evidence that the natural depletion curves all are downward decay curves. An EROI of more than ~3 then is what appears necessary to provide the energy for socially important tasks, such as maintaining government, legal and financial institutions, a transportation infrastructure, manufacturing, building construction and maintenance, and the lifestyles of all members of a given society.[84]

The social scientist Luke Kemp indicated that alternative sources of energy, such as solar panels, have a low EROI because they have low energy density, meaning they require a lot of land, and require substantial amounts of rare earth metals to produce.[1] Hall and colleagues reached the same conclusion. There is no on-site pollution, but the EROI of renewable energy sources may be too low for them to be considered a viable alternative to fossil fuels, which continue to provide the majority of the energy used by humans.[82]

The mathematician Safa Motesharrei and his collaborators showed that the use of non-renewable resources such as fossil fuels allows populations to grow to one order of magnitude larger than they would using renewable resources alone and as such is able to postpone societal collapse. However, when collapse finally comes, it is much more dramatic.[5][85] Tainter warned that in the modern world, if the supply of fossil fuels were somehow cut off, shortages of clean water and food would ensue, and millions would die in a few weeks in the worse-case scenario.[5]

Homer-Dixon asserted that a declining EROI was one of the reasons that the Roman Empire declined and fell. The historian Joseph Tainter made the same claim about the Maya Empire.[1]

Models of societal response

[edit]According to Joseph Tainter[86] (1990), too many scholars offer facile explanations of societal collapse by assuming one or more of the following three models in the face of collapse:

- The Dinosaur, a large-scale society in which resources are being depleted at an exponential rate, but nothing is done to rectify the problem because the ruling elite are unwilling or unable to adapt to those resources' reduced availability. In this type of society, rulers tend to oppose any solutions that diverge from their present course of action but favor intensification and commit an increasing number of resources to their present plans, projects, and social institutions.

- The Runaway Train, a society whose continuing function depends on constant growth (cf. Frederick Jackson Turner's Frontier Thesis). This type of society, based almost exclusively on acquisition (such as pillaging or exploitation), cannot be sustained indefinitely. The Assyrian, Roman and Mongol Empires, for example, all fractured and collapsed when no new conquests could be achieved.

- The House of Cards, a society that has grown to be so large and include so many complex social institutions that it is inherently unstable and prone to collapse. This type of society has been seen with particular frequency among Eastern Bloc and other communist nations, in which all social organizations are arms of the government or ruling party, such that the government must either stifle association wholesale (encouraging dissent and subversion) or exercise less authority than it asserts (undermining its legitimacy in the public eye).

Tainter's critique

[edit]Tainter argues that those models, though superficially useful, cannot severally or jointly account for all instances of societal collapse. Often, they are seen as interconnected occurrences that reinforce one another.

Tainter considers that social complexity is a recent and comparatively-anomalous occurrence, requiring constant support. He asserts that collapse is best understood by grasping four axioms. In his own words (p. 194):

- human societies are problem-solving organizations;

- sociopolitical systems require energy for their maintenance;

- increased complexity carries with it increased costs per capita; and

- investment in sociopolitical complexity as a problem-solving response reaches a point of declining marginal returns.

With those facts in mind, collapse can simply be understood as a loss of the energy needed to maintain social complexity. Collapse is thus the sudden loss of social complexity, stratification, internal and external communication and exchange, and productivity.

Toynbee's theory of decay

[edit]In his acclaimed 12-volume work, A Study of History (1934–1961), the British historian Arnold J. Toynbee explored the rise and fall of 28 civilizations and came to the conclusion that civilizations generally collapsed mainly by internal factors, factors of their own making, but external pressures also played a role.[1] He theorized that all civilizations pass through several distinct stages: genesis, growth, time of troubles, universal state, and disintegration.[87]

For Toynbee, a civilization is born when a "creative minority" successfully responds to the challenges posed by its physical, social, and political environment. However, the fixation on the old methods of the "creative minority" leads it to eventually cease to be creative and degenerate into merely a "dominant minority" (that forces the majority to obey without meriting obedience), which fails to recognize new ways of thinking. He argues that creative minorities deteriorate from a worship of their "former self", by which they become prideful, and they fail in adequately addressing the next challenge that they face. Similarly, the German philosopher Oswald Spengler discussed the transition from Kultur to Zivilisation in his The Decline of the West (1918).[87]

Toynbee argues that the ultimate sign a civilization has broken down is when the dominant minority forms a Universal State, which stifles political creativity. He states:

First the Dominant Minority attempts to hold by force - against all right and reason - a position of inherited privilege which it has ceased to merit; and then the Proletariat repays injustice with resentment, fear with hate, and violence with violence when it executes its acts of secession. Yet the whole movement ends in positive acts of creation - and this on the part of all the actors in the tragedy of disintegration. The Dominant Minority creates a universal state, the Internal Proletariat a universal church, and the External Proletariat a bevy of barbarian war-bands.

He argues that as civilizations decay, they form an "Internal Proletariat" and an "External Proletariat." The Internal proletariat is held in subjugation by the dominant minority inside the civilization, and grows bitter; the external proletariat exists outside the civilization in poverty and chaos and grows envious. He argues that as civilizations decay, there is a "schism in the body social", whereby abandon and self-control together replace creativity, and truancy and martyrdom together replace discipleship by the creative minority.

He argues that in that environment, people resort to archaism (idealization of the past), futurism (idealization of the future), detachment (removal of oneself from the realities of a decaying world), and transcendence (meeting the challenges of the decaying civilization with new insight, as a prophet). He argues that those who transcend during a period of social decay give birth to a new Church with new and stronger spiritual insights around which a subsequent civilization may begin to form after the old has died. Toynbee's use of the word 'church' refers to the collective spiritual bond of a common worship, or the same unity found in some kind of social order.

The historian Carroll Quigley expanded upon that theory in The Evolution of Civilizations (1961, 1979).[88] He argued that societal disintegration involves the metamorphosis of social instruments, which were set up to meet actual needs, into institutions, which serve their own interest at the expense of social needs.[89] However, in the 1950s, Toynbee's approach to history, his style of civilizational analysis, started to face skepticism from mainstream historians who thought it put an undue emphasis on the divine, which led to his academic reputation declining. For a time, however, Toynbee's Study remained popular outside academia. Interest revived decades later with the publication of The Clash of Civilizations (1997) by the political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, who viewed human history as broadly the history of civilizations and posited that the world after the end of the Cold War will be multipolar and one of competing major civilizations, which are divided by "fault lines."[87]

Systems science

[edit]Developing an integrated theory of societal collapse that takes into account the complexity of human societies remains an open problem.[49] Researchers currently have very little ability to identify internal structures of large distributed systems like human societies. Genuine structural collapse seems, in many cases, the only plausible explanation supporting the idea that such structures exist. However, until they can be concretely identified, scientific inquiry appears limited to the construction of scientific narratives,[90][49] using systems thinking for careful storytelling about systemic organization and change.

In the 1990s, the evolutionary anthropologist and quantitative historian Peter Turchin noticed that the equations used to model the populations of predators and preys can also be used to describe the ontogeny of human societies. He specifically examined how social factors such as income inequality were related to political instability. He found recurring cycles of unrest in historical societies such as Ancient Egypt, China, and Russia. He specifically identified two cycles, one long and one short. The long one, what he calls the "secular cycle," lasts for approximately two to three centuries. A society starts out fairly equal. Its population grows and the cost of labor drops. A wealthy upper class emerges, and life for the working class deteriorates. As inequality grows, a society becomes more unstable with the lower-class being miserable and the upper-class entangled in infighting. Exacerbating social turbulence eventually leads to collapse. The shorter cycle lasts for about 50 years and consists of two generations, one peaceful and one turbulent. Looking at US history, for example, Turchin identified times of serious sociopolitical instability in 1870, 1920, and 1970. He announced in 2010 that he had predicted that in 2020, the US would witness a period of unrest at least on the same level as 1970 because the first cycle coincides with the turbulent part of the second in around 2020. He also warned that the US was not the only Western nation under strain.[5]

However, Turchin's model can only paint the broader picture and cannot pinpoint how bad things can get and what precisely triggers a collapse. The mathematician Safa Motesharrei also applied predator-prey models to human society, with the upper class and the lower class being the two different types of "predators" and natural resources being the "prey." He found that either extreme inequality or resource depletion facilitates a collapse. However, a collapse is irreversible only if a society experiences both at the same time, as they "fuel each other."[5]

See also

[edit]- Apocalypticism

- Decadence

- Doomer

- Doomsday cult

- Human extinction

- John B. Calhoun's mouse experiments

- Lost city

- Millenarianism

- Ruins

- Survivalism

- Social alienation

- Weltschmerz

- Malthusian and environmental collapse themes

- Collapsology

- Behavioral sink – rat colony collapse

- Catastrophism

- Earth 2100

- Ecological collapse

- Global catastrophic risk

- Human overpopulation

- Medieval demography

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

- Cultural and institutional collapse themes

- Civil war

- Degrowth

- Economic collapse

- Failed state

- Fragile state

- Group cohesiveness

- Language death

- Progress trap

- Social cycle theory

- Sociocultural evolution

- State collapse

- Urban decay

- Systems science

- Failure mode and effects analysis

- Fault tree analysis

- Hazard analysis

- Risk assessment

- Systems engineering

Notes

[edit]- ^ See the end of the section 'Demographic dynamics' for a chart of the death rate (per 100,000) of the Thirty Years' War compared to other armed conflicts between 1400 and 2000.

- ^ The Vandals thus made themselves the origin of the modern English word 'vandalism'.

- ^ North and South here are with respect to the Gianh River, which is close to the Bến Hải River, or approximately the 17th Parallel, used for the Partition of Vietnam after the First Indochinese War and before the Second Indochinese War, commonly known as the Vietnam War.

- ^ For example, during the Napoleonic Wars, for every British soldier who got killed in action, eight died of disease. During the American Civil War, two-thirds of the almost 700,000 dead were victims of smallpox, dysentery, typhoid, malaria, and pneumonia, collectively referred to as the "Third Army."

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kemp, Luke (18 February 2019). "Are we on the road to civilisation collapse?". BBC Future. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Brozović, Danilo (2023). "Societal collapse: A literature review". Futures. 145: 103075. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2022.103075.

- ^ a b c Spinney, Laura (18 February 2020). "Panicking about societal collapse? Plunder the bookshelves". Nature. 578 (7795): 355–357. Bibcode:2020Natur.578..355S. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00436-3.

- ^ Scheffer, Marten; van Nes, Egbert H.; Kemp, Luke; Kohler, Timothy A.; Lenton, Timothy M.; Xu, Chi (28 November 2023). "The vulnerability of aging states: A survival analysis across premodern societies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120 (48): e2218834120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12018834S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2218834120. PMC 10691336. PMID 37983501.

- ^ a b c d e f Spinney, Laura (17 January 2018). "End of days: Is Western civilisation on the brink of collapse?". New Scientist.

- ^ Pasha-Robinson, Lucy (7 January 2017). "'Society could end in less than a decade,' predicts academic". The Independent. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Ben Ehrenreich (4 November 2020). "How Do You Know When Society Is About to Fall Apart?". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b Joseph A. Tainter (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. New Studies in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. "What is collapse? 'Collapse' is a broad term that can cover many kinds of processes. It means different things to different people. Some see collapse as a thing that could happen only to societies organized at the most complex level. To them, the notion of tribal societies or village horticulturalists collapsing will seem odd. Others view collapse in terms of economic disintegration, of which the predicted end of industrial society is the ultimate expression. Still others question the very utility of the concept, pointing out that art styles and literary traditions often survive political decentralization. Collapse, as viewed in the present work, is a political process. It may, and often does, have consequences in such areas as economics, art, and literature, but it is fundamentally a matter of the sociopolitical sphere. A society has collapsed when it displays a rapid, significant loss of an established level of sociopolitical complexity. The term 'established level' is important. To qualify as an instance of collapse a society must have been at, or developing toward, a level of complexity for more than one or two generations. The demise of the Carolingian Empire, thus, is not a case of collapse - merely an unsuccessful attempt at empire building. The collapse, in turn, must be rapid - taking no more than a few decades - and must entail a substantial loss of sociopolitical structure. Losses that are less severe, or take longer to occur, are to be considered cases of weakness and decline. [...] The fall of the Roman Empire is, in the West, the most widely known instance of collapse, the one which comes most readily to popular thought." (Pages 4-5)

- ^ Patricia A. McAnany; Norman Yoffee, eds. (2009). Questioning Collapse: Human Resilience, Ecological Vulnerability, and the Aftermath of Empire.

- ^ Ronald K. Faulseit, ed. (2016). Beyond Collapse: Archaeological Perspectives on Resilience, Revitalization, and Transformation in Complex Societies. Occasional Paper. Southern Illinois University Press.

- ^ a b Shmuel Eisenstadt (1991). "Beyond Collapse". In Norman Yoffee; George L. Cowgill (eds.). The Collapse of Ancient States and Civilizations. p. 242.

- ^ Kemp, Luke (19 February 2019). "The lifespans of ancient civilisations". BBC Future. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Leonie J. Pearson; Craig J. Pearson (24 July 2012). "Societal collapse or transformation, and resilience". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (30). National Academy of Sciences: E2030–E2031. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E2030P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1207552109. PMC 3409784. PMID 22730464.

- ^ Nuwer, Rachel (18 April 2017). "How Western civilisation could collapse". BBC Future. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Joseph A. Tainter (2006). "Archaeology of Overshoot and Collapse". Annual Review of Anthropology. 35: 59–74. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123136.

- ^ a b Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Penguin Books, 2005 and 2011 (ISBN 978-0-241-95868-1).

- ^ Mark Damen (28 January 2017). "The Myth of the "Fall" of Rome". Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ a b Pillalamarri, Akhilesh (2 June 2016). "Revealed: The Truth Behind the Indus Valley Civilization's 'Collapse'". The Diplomat – The Diplomat is a current-affairs magazine for the Asia-Pacific, with news and analysis on politics, security, business, technology and life across the region. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ Choi, Charles (24 August 2020). "Ancient megadrought may explain civilization's 'missing millennia' in Southeast Asia". Science Magazine. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Collapse of civilizations worldwide defines youngest unit of the Geologic Time Scale". News and Meetings. International Commission on Stratigraphy. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ National Geographic 2007, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Robbins-Schug, G.; Gray, K.M.; Mushrif, V.; Sankhyan, A.R. (November 2012). "A Peaceful Realm? Trauma and Social Differentiation at Harappa" (PDF). International Journal of Paleopathology. 2 (2–3): 136–147. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2012.09.012. PMID 29539378. S2CID 3933522.

- ^ Robbins-Schug, G.; Blevins, K. Elaine; Cox, Brett; Gray, Kelsey; Mushrif-Tripathy, Veena (December 2013). "Infection, Disease, and Biosocial Process at the End of the Indus Civilization". PLOS ONE. 0084814 (12): e84814. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...884814R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084814. PMC 3866234. PMID 24358372.

- ^ Lawler, A. (6 June 2008). "Indus Collapse: The End or the Beginning of an Asian Culture?". Science Magazine. 320 (5881): 1282–1283. doi:10.1126/science.320.5881.1281. PMID 18535222. S2CID 206580637.

- ^ Grijalva, K.A.; Kovach, L.R.; Nur, A.M. (1 December 2006). "Evidence for Tectonic Activity During the Mature Harappan Civilization, 2600-1800 BCE". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2006: T51D–1553. Bibcode:2006AGUFM.T51D1553G.

- ^ Prasad, Manika; Nur, Amos (1 December 2001). "Tectonic Activity during the Harappan Civilization". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2001: U52B–07. Bibcode:2001AGUFM.U52B..07P.

- ^ Kovach, Robert L.; Grijalva, Kelly; Nur, Amos (1 October 2010). Earthquakes and civilizations of the Indus Valley: A challenge for archaeoseismology. Geological Society of America Special Papers. Vol. 471. pp. 119–127. doi:10.1130/2010.2471(11). ISBN 978-0-8137-2471-3.

- ^ Wilson, R. Mark (1 September 2020). "An Alaskan volcano, climate change, and the history of ancient Rome". Physics Today. 73 (9): 17–20. Bibcode:2020PhT....73i..17W. doi:10.1063/PT.3.4563.

- ^ Hawkins, Ed (30 January 2020). "2019 years". climate-lab-book.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. ("The data show that the modern period is very different to what occurred in the past. The often quoted Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age are real phenomena, but small compared to the recent changes.")

- ^ a b c Zhang, David D.; Lee, Harry F.; Wang, Cong; Li, Baosheng; Pei, Qing; Zhang, Jane; An, Yulun (18 October 2011). "The causality analysis of climate change and large-scale human crisis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (42): 17296–17301. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104268108. PMC 3198350. PMID 21969578. S2CID 33451915.

- ^ a b c Zhang, David D.; Brecke, Peter; Lee, Harry F.; He, Yuan-Qing; Zhang, Jane (4 December 2007). Ehrlich, Paul R. (ed.). "Global climate change, war, and population decline in recent human history". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (49): 19214–19219. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10419214Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703073104. PMC 2148270. PMID 18048343.

- ^ National Geographic 2007, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Rascovan, N; Sjögren, KG; Kristiansen, K (2019). "Emergence and Spread of Basal Lineages of Yersinia pestis during the Neolithic Decline". Cell. 176 (1): 295–305.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.005. PMID 30528431.

- ^ "Steppe migrant thugs pacified by Stone Age farming women". ScienceDaily. Faculty of Science - University of Copenhagen. 4 April 2017.

- ^ Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei (11 June 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- ^ National Geographic 2007, pp. 94–97.

- ^ National Geographic 2007, pp. 82–83.

- ^ The Great Mosque of Tlemcen, MuslimHeritage.com

- ^ Populations Crises and Population Cycles Archived 27 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Claire Russell and W.M.S. Russell

- ^ National Geographic 2007, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Ibn Battuta's Trip: Part Three - Persia and Iraq (1326 - 1327) Archived 23 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ National Geographic 2007, pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b National Geographic 2007, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Elijah Coleman Bridgman; Samuel Wells Willaims (1847). The Chinese Repository. proprietors. pp. 584–.

- ^ Weber, N. (2012). The destruction and assimilation of Campā (1832-35) as seen from Cam sources. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 43(1), 158-180. Retrieved 3 June 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/41490300

- ^ Jean-François Hubert (8 May 2012). The Art of Champa. Parkstone International. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-1-78042-964-9.

- ^ Dharma, Po. "The Uprisings of Katip Sumat and Ja Thak Wa (1833-1835)". Cham Today. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 141–. ISBN 0-87727-138-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Butzer, Karl W. (6 March 2012). "Collapse, environment, and society". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (10): 3632–3639. doi:10.1073/pnas.1114845109. PMC 3309741. PMID 22371579.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (2 September 2009). "Sea Peoples". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ National Geographic 2007, pp. 100–103.

- ^ a b Johnson, Ben. "The Great Flood and Great Famine of 1314". Historic UK. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ a b Fritts, Rachel (13 December 2019). "One of Europe's worst famines likely caused by devastating floods". Earth Sciences. Phys.org. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ a b Cochran, Gregory; Harpending, Henry (2009). "Chapter 4: Consequences of Agriculture". The 10,000 Year Explosion: How Civilization Accelerated Human Evolution. United States of America: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02042-3.

- ^ a b c d e f LePan, Nicholas (14 March 2020). "Visualizing the History of Pandemics". The Visual Capitalist. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ a b c Rosenwald, Michael S. (7 April 2020). "History's deadliest pandemics, from ancient Rome to modern America". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ a b Horgan, John (2 May 2019). "Antonine Plague". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ National Geographic 2007, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c d Walsh, Bryan (25 March 2020). "Covid-19: The history of pandemics". BBC Future. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ a b Latham, Andrew (1 October 2020). "How three prior pandemics triggered massive societal shifts". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Robert Tignor et al. Worlds Together, Worlds Apart A History of the World: From the Beginnings of Humankind to the Present (2nd ed. 2008) ch. 11 pp. 472–75 and map pp. 476–77

- ^ a b Barras, Vincent; Greub, Gilbert (June 2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 498. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

In the Middle Ages, a famous although controversial example is offered by the siege of Caffa (now Feodossia in Ukraine/Crimea), a Genovese outpost on the Black Sea coast, by the Mongols. In 1346, the attacking army experienced an epidemic of bubonic plague. The Italian chronicler Gabriele de' Mussi, in his Istoria de Morbo sive Mortalitate quae fuit Anno Domini 1348, describes quite plausibly how the plague was transmitted by the Mongols by throwing diseased cadavers with catapults into the besieged city, and how ships transporting Genovese soldiers, fleas and rats fleeing from there brought it to the Mediterranean ports. Given the highly complex epidemiology of plague, this interpretation of the Black Death (which might have killed > 25 million people in the following years throughout Europe) as stemming from a specific and localized origin of the Black Death remains controversial. Similarly, it remains doubtful whether the effect of throwing infected cadavers could have been the sole cause of the outburst of an epidemic in the besieged city.

- ^ Andrew G. Robertson, and Laura J. Robertson. "From asps to allegations: biological warfare in history," Military medicine (1995) 160#8 pp. 369–73.

- ^ Rakibul Hasan, "Biological Weapons: covert threats to Global Health Security." Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies (2014) 2#9 p. 38. online Archived 17 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "BBC - History - British History in depth: Black Death: The lasting impact". BBC.

- ^ a b c d Cochran, Gregory; Harpending, Henry (2010). "Chapter 6: Expansions". The 10,000 Year Explosion: How Civilization Accelerated Human Evolution. United States of America: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02042-3.

- ^ "BBC - History - British History in depth: Smallpox: Eradicating the Scourge". BBC.

- ^ "Guns Germs & Steel: Variables. Smallpox". PBS.

- ^ Bos, Kirsten I.; Harkins, Kelly M.; Herbig, Alexander; Coscolla, Mireia; Weber, Nico; Comas, Iñaki; Forrest, Stephen A.; Bryant, Josephine M.; Harris, Simon R. (23 October 2014). "Pre-Columbian mycobacterial genomes reveal seals as a source of New World human tuberculosis". Nature. 514 (7523): 494–497. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..494B. doi:10.1038/nature13591. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 4550673. PMID 25141181.

- ^ Smallpox Through History. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009.

- ^ Duncan, Mike (2017). The Storm Before The Storm. PublicAffairs. p. 29. ISBN 9781610397216.

- ^ "The Welfare State: The History Behind It – Government Policy: The Pros and (E)cons". sites.psu.edu. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ "Rome's Runaway Inflation: Currency Devaluation in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries | Mises Institute". mises.org. 5 January 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ Population crises and cycles in history Archived 5 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, A review of the book Population Crises and Population cycles by Claire Russell and W M S Russell.

- ^ Dynamics of Indigenous Demographic Fluctuations: Lessons from Sixteenth-Century Cusco, Peru Archived 25 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine R. Alan Covey, Geoff Childs, Rebecca Kippen Source: Current Anthropology, Vol. 52, No. 3 (June 2011), pp. 335-360: The University of Chicago Press

- ^ "Population crises and cycles in history - OzIdeas". 5 April 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011.

- ^ a b Turchin, Peter (2 July 2008). "Arise 'cliodynamics'". Nature. 454 (7200): 34–5. Bibcode:2008Natur.454...34T. doi:10.1038/454034a. PMID 18596791. S2CID 822431.

- ^ a b "Why a two-state solution doesn't guarantee peace in the Middle East". Washington Examiner. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Turchin, Peter (2013). "Modeling Social Pressures Toward Political Instability". Cliodynamics. 4 (2). doi:10.21237/C7clio4221333.

- ^ a b Tainter, Joseph A. (1990). The Collapse of Complex Societies (1st paperback ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38673-X.

- ^ Jared Diamond on why societies collapse Archived 13 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine TED talk, Feb 2003

- ^ a b c Hall, Charles A.S.; Lambert, Jessica G.; Balogh, Stephen B. (January 2014). "EROI of Different Fuels and the Implications for Society". Energy Policy. 64: 141–152. Bibcode:2014EnPol..64..141H. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.049.

- ^ Homer-Dixon, Thomas (2007), "The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity and the Renewal of Civilization" (Knopf, Canada)

- ^ a b Hall, Charles 2009 "What is the Minimum EROI that a Sustainable Society Must Have" ENERGIES [1]

- ^ Safa Motesharrei, Jorge Rivas, Eugenia Kalnay, Ghassem R. Asrar, Antonio J. Busalacchi, Robert F. Cahalan, Mark A. Cane, Rita R. Colwell, Kuishuang Feng, Rachel S. Franklin, Klaus Hubacek, Fernando Miralles-Wilhelm, Takemasa Miyoshi, Matthias Ruth, Roald Sagdeev, Adel Shirmohammadi, Jagadish Shukla, Jelena Srebric, Victor M. Yakovenko, Ning Zeng (December 2016). "Modeling sustainability: population, inequality, consumption, and bidirectional coupling of the Earth and Human Systems". National Science Review. 3 (4): 470–494. doi:10.1093/nsr/nww081. PMC 7398446. PMID 32747868.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tainter, Joseph (1990), The Collapse of Complex Societies (Cambridge University Press) pp. 59-60.

- ^ a b c Kumar, Krishan (3 October 2014). "The Return of Civilization—and of Arnold Toynbee?". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 56 (4): 815–843. doi:10.1017/S0010417514000413.

- ^ "The Evolution of Civilizations - An Introduction to Historical Analysis (1979)" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Harry J Hogan in the foreword (p17) and Quigley in the conclusion (p416) to Carroll Quigley (1979). The evolution of civilizations: an introduction to historical analysis. Liberty Press. ISBN 0-913966-56-8. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ T.F. Allen, J.A. Tainter et al. 2001 Dragnet Ecology: The Privilege of Science in a Postmodern World. BioScience

Bibliography

[edit]- Essential Visual History of the World. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. 2007. ISBN 978-1-4262-0091-5. OCLC 144922970.

Further reading

[edit]- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Ehrlich, Anne H. (9 January 2013). "Can a collapse of global civilization be avoided?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 280 (1754): 20122845. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.2845. PMC 3574335. PMID 23303549. Comment by Prof. Michael Kelly, disagreeing with the paper by Ehrlich and Ehrlich; and response by the authors

- Homer-Dixon, Thomas. (2006). The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity, and the Renewal of Civilization. Washington DC: Island Press.

- Huesemann, Michael H., and Joyce A. Huesemann (2011). Technofix: Why Technology Won’t Save Us or the Environment, Chapter 6, "Sustainability or Collapse", New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada, ISBN 978-0-86571-704-6, 464 pp.

- Motesharrei, Safa; Rivas, Jorge; Kalnay, Eugenia (2014). "Human and nature dynamics (HANDY): Modeling inequality and use of resources in the collapse or sustainability of societies". Ecological Economics. 101: 90–102. Bibcode:2014EcoEc.101...90M. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.02.014.

- Wright, Ronald. (2004). A Short History of Progress. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-1547-2.