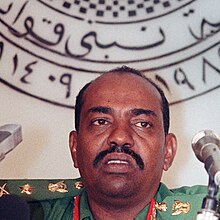

Omar al-Bashir

Omar al-Bashir | |

|---|---|

عمر البشير | |

Al-Bashir in 2009 | |

| 4th President of Sudan | |

| In office 16 October 1993 – 11 April 2019 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Vice President | See list |

| Preceded by | Himself as Chairman of the RCC |

| Succeeded by | Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf (as Chairman of the Transitional Military Council) |

| Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation | |

| In office 30 June 1989 – 16 October 1993 | |

| Deputy | Zubair Mohamed Salih |

| Preceded by | Ahmed al-Mirghani (as President) |

| Succeeded by | Himself as President |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir 1 January 1944 Hosh Bannaga, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan |

| Political party | National Congress Party (1992–2019) |

| Spouse(s) | Fatima Khalid Widad Babiker Omer |

| Alma mater | Egyptian Military Academy |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1960–2019 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Criminal details | |

| Criminal status | Claimed by ICC |

| Conviction(s) | Money laundering Corruption |

| Criminal penalty | Two years in prison |

Date apprehended | 17 April 2019 |

| Imprisoned at | Incarcerated at the Kobar Prison, Khartoum, Sudan |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

President of Sudan 1989-2019

Government

Wars

|

||

Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir[a] (born 1 January 1944) is a Sudanese former military officer and politician who served as Sudan's head of state under various titles from 1989 until 2019, when he was deposed in a coup d'état.[2] He was subsequently incarcerated, tried and convicted on multiple corruption charges.[3][4] He came to power in 1989 when, as a brigadier general in the Sudanese Army, he led a group of officers in a military coup that ousted the democratically elected government of prime minister Sadiq al-Mahdi after it began negotiations with rebels in the south; he subsequently replaced President Ahmed al-Mirghani as head of state.[5] He was elected three times as president in elections that have been under scrutiny for electoral fraud.[6] In 1992, al-Bashir founded the National Congress Party, which remained the dominant political party in the country until 2019.[7] In March 2009, al-Bashir became the first sitting head of state to be indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC), for allegedly directing a campaign of mass killing, rape, and pillage against civilians in Darfur.[8] On 11 February 2020, the Government of Sudan announced that it had agreed to hand over al-Bashir to the ICC for trial.[9]

In October 2005, al-Bashir's government negotiated an end to the Second Sudanese Civil War,[10] leading to a referendum in the south, resulting in the separation of the south as the country of South Sudan. In the Darfur region, he oversaw the War in Darfur that resulted in death tolls of around 10,000 according to the Sudanese Government,[11] but most sources suggest between 200,000[12] and 400,000.[13][14][15] During his presidency, there were several violent struggles between the Janjaweed militia and rebel groups such as the Sudanese Liberation Army (SLA) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) in the form of guerrilla warfare in the Darfur region. The civil war displaced[16] over 2.5 million people out of a total population of 6.2 million in Darfur[17] and created a crisis in the diplomatic relations between Sudan and Chad.[18] The rebels in Darfur lost the support from Libya after the death of Muammar Gaddafi and the collapse of his regime in 2011.[19][20][21]

In July 2008, the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Luis Moreno Ocampo, accused al-Bashir of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes in Darfur.[22] The court issued an arrest warrant for al-Bashir on 4 March 2009 on counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, but ruled that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute him for genocide.[23][24] However, on 12 July 2010, the court issued a second warrant containing three separate counts of genocide. The new warrant, like the first, was delivered to the Sudanese government, which did not recognize either the warrant or the ICC.[24] The indictments do not allege that Bashir personally took part in such activities; instead, they say that he is "suspected of being criminally responsible, as an indirect co-perpetrator".[25] The court's decision was opposed by the African Union, Arab League and Non-Aligned Movement as well as the governments of Libya, Somalia, Jordan, Turkey, Egypt, South Sudan, Djibouti, Eritrea, Pakistan, Algeria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, Palestine, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Morocco, Lebanon, Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.[26][27]

From December 2018 onwards, al-Bashir faced large-scale protests which demanded his removal from power. On 11 April 2019, Bashir was ousted in a military coup d'état.[28][29] In September 2019, Bashir was replaced by the Transitionary Military Council which transferred executive power to a mixed civilian–military Sovereignty Council and a civilian prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok. Two months later, the Forces of Freedom and Change alliance (which holds indirect political power during the 39-month Sudanese transition to democracy), Hamdok, and Sovereignty Council member Siddiq Tawer stated that Bashir would be eventually transferred to the ICC. He was convicted of corruption in December of that year and sentenced to two years in prison.[30][31][32] His trial regarding his role in the coup that brought him into power started on 21 July 2020.[33]

Early and family life

[edit]Al-Bashir was born on 1 January 1944 in Hosh Bannaga,[34] a village on the outskirts of Shendi, just north of the capital, Khartoum, to a family that hails from the Ja'alin tribe of northern Sudan. His mother was Hedieh Mohamed al-Zain, who died in 2019.[35][36][37] His father, Hassan ibn Ahmed, was a smalltime dairy farmer. He is the second among twelve brothers and sisters, his younger brother Othman was killed in South Sudan during his presidency.[38] His uncle, Al Taib Mustafa, was a journalist, politician, and noted opponent of South Sudan.[39] As a boy, he was nicknamed 'Omeira' – Little Omar.[40] He belongs to the Banu Bedaria, a Bedouin tribe belonging to the larger Ja'alin coalition,[41] a Sudanese Arab tribe in middle north of Sudan (once a part of the Kingdom of Egypt and Sudan). As a child, Al-Bashir loved football. "Always in defence," a cousin said. "That's why he went into the army." He received his primary education there, and his family later moved to Khartoum North where he completed his secondary education and became a supporter of Al-Hilal. Al-Bashir is married to his cousin Fatima Khalid. He also has a second wife named Widad Babiker Omer, who had a number of children with her first husband Ibrahim Shamsaddin, a member of the Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation who had died in a helicopter crash. Al-Bashir does not have any children of his own.[42][40]

In 1975, al-Bashir was sent to the United Arab Emirates as the Sudanese military attaché. When he returned home, al-Bashir was made a garrison commander. In 1981, al-Bashir returned to his paratroop background when he became the commander of an armored parachute brigade.[43]

The Sudanese Ministry of Defense website says that al-Bashir was in the Western Command from 1967 to 1969 and then the Airborne Forces from 1969 to 1987 until he was appointed commander of the 8th Infantry Brigade (independent) from the period 1987 to 30 June 1989.[44]

Presidency

[edit]Coup d'état

[edit]

When he returned to Sudan as a colonel in the Sudanese Army, al-Bashir led a group of army officers in ousting the unstable coalition government of Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi in a bloodless military coup on 30 June 1989.[5] Under al-Bashir's leadership, the new military government suspended political parties and introduced an Islamic legal code on the national level.[45] He then became chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation (a newly established body with legislative and executive powers for what was described as a transitional period), and assumed the posts of chief of state, prime minister, chief of the armed forces, and Minister of Defence.[46] Subsequent to al-Bashir's promotion to the chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation, he allied himself with Hassan al-Turabi, the leader of the National Islamic Front, who, along with al-Bashir, began institutionalizing Sharia law in the northern part of Sudan. Further on, al-Bashir issued purges and executions of people whom he alleged to be coup leaders in the upper ranks of the army, the banning of associations, political parties, and independent newspapers, as well as the imprisonment of leading political figures and journalists.[47]

On 16 October 1993, al-Bashir's increased his power when he appointed himself President of the country, after which he disbanded the Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation and all other rival political parties. The executive and legislative powers of the council were later given to al-Bashir completely.[48] In the early 1990s, al-Bashir's administration gave the green light to float a new currency called Sudanese dinar to replace the battered old Sudanese pound that had lost 90 percent of its worth during the turbulent 1980s; the currency was later changed back to pounds, but at a much higher rate. He was later elected president (with a five-year term) in the 1996 national election, where he was the only candidate legally allowed to run for election.[49]

Elections

[edit]Omar al-Bashir was elected president (with a five-year term) in the 1996 national election[49] and Hassan al-Turabi was elected to a seat in the National Assembly where he served as speaker of the National Assembly "during the 1990s".[50] In 1998, al-Bashir and the Presidential Committee put into effect a new constitution, allowing limited political associations in opposition to al-Bashir's National Congress Party and his supporters to be formed. On 12 December 1999, al-Bashir sent troops and tanks against parliament and ousted Hassan al-Turabi, the speaker of parliament, in a palace coup.[51]

He was reelected by popular vote for a five-year term during the 2000 Sudanese general election.[52]

From 2005 to 2010, a transitional government was set up under a 2005 peace accord that ended the 21-year long Second Sudanese Civil War and saw the formation of a power-sharing agreement between Salva Kiir's Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) and al Bashir's National Congress Party (NCP).[53]

Al-Bashir was reelected president in the 2010 Sudanese general election with 68% of the popular vote;[54] while Salva Kiir was elected President of Southern Sudan. These elections were agreed on earlier in the 2005 peace accord.[53] The election was marked by corruption, intimidation, and inequality. European observers, from the European Union and the Carter Center, criticised the polls as "not meeting international standards". Candidates opposed to the SPLM said they were often detained or stopped from campaigning. Sudan Democracy First, an umbrella organisation in the north, put forward what it called strong evidence of rigging by al-Bashir's NCP. The Sudanese Network for Democracy and Elections (Sunde) spoke of harassment and intimidation in the south, by the security forces of the SPLM.[6]

Al-Bashir had achieved economic growth in Sudan.[55] This was pushed further by the drilling and extraction of oil-[55] However, economic growth was not shared by all. Headline inflation in 2012 approached the threshold of chronic inflation (period average 36%), about 11% up from the budget projection of 2012 reflecting the combined effects of inflationary financing, the depreciation of the exchange rate, and the continued removal of subsidies, as well as high food and energy prices. This economic downturn prompted cost of living riots that erupted into Arab Spring-style anti-government demonstrations, raising discontent within the Sudanese Workers' Trade Union Federation (SWTUF). They threatened to hold nationwide strikes in support of higher wages. The continued deterioration in the value of the Sudanese pound (SDG) posed grave downside risks to already soaring inflation. This, coupled with the economic slowdown, presents serious challenges to the implementation of the approved Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (I-PRSP).[56]

Tensions with Hassan al-Turabi

[edit]In the mid-1990s, a feud between al-Bashir and al-Turabi began, mostly due to al-Turabi's links to Islamic fundamentalist groups, as well as allowing them to operate out of Sudan, even personally inviting Osama bin Laden to the country.[57] The United States had listed Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism since 1993,[58] mostly due to al-Bashir and Hassan al-Turabi taking complete power in the early 1990s.[59] U.S. firms have been barred from doing business in Sudan since 1997.[60] In 1998, the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum was destroyed by a U.S. cruise missile strike because of its alleged production of chemical weapons and links to al-Qaeda. However the U.S. State Department Bureau of Intelligence and Research wrote a report in 1999 questioning the attack on the factory, suggesting that the connection to bin Laden was not accurate; James Risen reported in The New York Times: "Now, the analysts renewed their doubts and told Assistant Secretary of State Phyllis Oakley that the C.I.A.'s evidence on which the attack was based was inadequate. Ms. Oakley asked them to double-check; perhaps there was some intelligence they had not yet seen. The answer came back quickly: There was no additional evidence. Ms. Oakley called a meeting of key aides and a consensus emerged: Contrary to what the Administration was saying, the case tying Al Shifa to Mr. bin Laden or to chemical weapons was weak."[61]

After being re-elected president of Sudan with a five-year-term in the 1996 election with 75.7% of the popular vote,[62] al-Bashir issued the registration of legalized political parties in 1999 after being influenced by al-Turabi. Rival parties such as the Liberal Democrats of Sudan and the Alliance of the Peoples' Working Forces, headed by former Sudanese President Gaafar Nimeiry, were established and were allowed to run for election against al-Bashir's National Congress Party, however, they failed to achieve significant support, and al-Bashir was re-elected president, receiving 86.5% of the popular vote in the 2000 presidential election. At the legislative elections that same year, al-Bashir's National Congress Party won 355 out of 360 seats, with al-Turabi as its chairman. However, after al-Turabi introduced a bill to reduce the president's powers, prompting al-Bashir to dissolve parliament and declare a state of emergency, tensions began to rise between al-Bashir and al-Turabi. Reportedly, al-Turabi was suspended as chairman of National Congress Party, after he urged a boycott of the president's re-election campaign. Then, a splinter-faction led by al-Turabi, the Popular National Congress Party (PNC) signed an agreement with Sudan People's Liberation Army, which led al-Bashir to believe that they were plotting to overthrow him and the government.[62]

Further on, al-Turabi's influence and that of his party's "'internationalist' and ideological wing" waned "in favor of the 'nationalist' or more pragmatic leaders who focus on trying to recover from Sudan's disastrous international isolation and economic damage that resulted from ideological adventurism".[63] At the same time, Sudan worked to appease the United States and other international critics by expelling members of Egyptian Islamic Jihad and encouraging bin Laden to leave.[64]

On al-Bashir's orders, al-Turabi was imprisoned based on allegations of conspiracy in 2000 before being released in October 2003.[65] Al-Turabi was again imprisoned in March 2004[66] and released in July 2005, at the height of the peace agreement in the civil war.[67][68]

Engagement with the U.S. and European countries

[edit]

From the early 1990s, after al-Bashir assumed power, Sudan backed Iraq in its invasion of Kuwait[69][70] and was accused of harboring and providing sanctuary and assistance to Islamic terrorist groups. Carlos the Jackal, Osama bin Laden, Abu Nidal and others labeled "terrorist leaders" by the United States and its allies resided in Khartoum. Sudan's role in the Popular Arab and Islamic Congress (PAIC), spearheaded by Hassan al-Turabi, represented a matter of great concern to the security of American officials and dependents in Khartoum, resulting in several reductions and evacuations of American personnel from Khartoum in the early to mid 1990s.[71]

Sudan's Islamist links with international terrorist organizations represented a special matter of concern for the American government, leading to Sudan's 1993 designation as a state sponsor of terrorism and a suspension of U.S. Embassy operations in Khartoum in 1996. In late 1994, in an initial effort to reverse his nation's growing image throughout the world as a country harboring terrorists, Bashir secretly cooperated with French special forces to orchestrate the capture and arrest on Sudanese soil of Carlos the Jackal.[72]

In early 1996, al-Bashir authorized his Defense Minister at the time, El Fatih Erwa, to make a series of secret trips to the United States[73] to hold talks with American officials, including officers of the CIA and United States Department of State about American sanctions policy against Sudan and what measures might be taken by the Bashir regime to remove the sanctions. Erwa was presented with a series of demands from the United States, including demands for information about Osama bin Laden and other radical Islamic groups. The US demand list also encouraged Bashir's regime to move away from activities, such as hosting the Popular Arab and Islamic Congress, that impinged on Sudanese efforts to reconcile with the West. Sudan's Mukhabarat (central intelligence agency) spent half a decade amassing intelligence data on bin Laden and a wide array of Islamists through their periodic annual visits for the PAIC conferences.[74] In May 1996, after the series of Erwa secret meetings on US soil, the Clinton Administration demanded that Sudan expel Bin Laden. Bashir complied.[75]

Controversy erupted about whether Sudan had offered to extradite bin Laden in return for rescinding American sanctions that were interfering with Sudan's plans to develop oil fields in southern areas of the country. American officials insisted the secret meetings were agreed only to pressure Sudan into compliance on a range of anti-terrorism issues. The Sudanese insisted that an offer to extradite bin Laden had been made in a secret one-on-one meeting at a Fairfax hotel between Erwa and the then CIA Africa Bureau chief on condition that Washington end sanctions against Bashir's regime. Ambassador Timothy M. Carney attended one of the Fairfax hotel meetings. In a joint opinion piece in the Washington Post Outlook Section in 2003, Carney and Ijaz argued that in fact the Sudanese had offered to extradite bin Laden to a third country in exchange for sanctions relief.[76]

In August 1996, American hedge-fund manager Mansoor Ijaz traveled to Sudan and met with senior officials including al-Turabi and al-Bashir. Ijaz asked Sudanese officials to share intelligence data with US officials on bin Laden and other Islamists who had traveled to and from Sudan during the previous five years. Ijaz conveyed his findings to US officials upon his return, including Sandy Berger, then Clinton's deputy national security adviser, and argued for the US to constructively engage the Sudanese and other Islamic countries.[77] In April 1997, Ijaz persuaded al-Bashir to make an unconditional offer of counterterrorism assistance in the form of a signed presidential letter that Ijaz delivered to Congressman Lee H. Hamilton by hand.[78]

In late September 1997, months after the Sudanese overture (made by al-Bashir in the letter to Hamilton), the U.S. State Department, under Secretary of State Madeleine Albright's directive, first announced it would return American diplomats to Khartoum to pursue counterterrorism data in the Mukhabarat's possession. Within days, the U.S. reversed that decision[79] and imposed harsher and more comprehensive economic, trade, and financial sanctions against Sudan, which went into effect in October 1997.[80] In August 1998, in the wake of the East Africa embassy bombings, the U.S. launched cruise missile strikes against Khartoum.[81] U.S. Ambassador to Sudan, Tim Carney, departed post in February 1996[82] and no new ambassador was designated until December 2019, when U.S. president Donald Trump's administration reached an agreement with the new Sudanese government to exchange ambassadors.[83]

Al-Bashir announced in August 2015 that he would travel to New York in September to speak at the United Nations. It was unclear to date if al-Bashir would have been allowed to travel, due to previous sanctions.[84]

South Sudan

[edit]

When al-Bashir took power the Second Sudanese Civil War had been ongoing for nine years. The war soon effectively developed into a conflict between the Sudan People's Liberation Army and al-Bashir's government. The war resulted in millions of southerners being displaced, starved, and deprived of education and health care, with almost two million casualties.[85] Because of these actions, various international sanctions were placed on Sudan. International pressure intensified in 2001, however, and leaders from the United Nations called for al-Bashir to make efforts to end the conflict and allow humanitarian and international workers to deliver relief to the southern regions of Sudan.[86] Much progress was made throughout 2003. The peace was consolidated with the official signing by both sides of the Nairobi Comprehensive Peace Agreement 9 January 2005, granting Southern Sudan autonomy for six years, to be followed by a referendum on independence. It created a co-vice president position and allowed the north and south to split oil deposits equally, but also left both the north's and south's armies in place. John Garang, the south's peace agreement appointed co-vice president, died in a helicopter crash on 1 August 2005, three weeks after being sworn in.[87] This resulted in riots, but the peace was eventually re-established[88] and allowed the southerners to vote in a referendum of independence at the end of the six-year period.[89] On 9 July 2011, following a referendum, the region of Southern Sudan split off from Sudan to form South Sudan.[90]

War in Darfur

[edit]

Since 1968, Sudanese politicians had attempted to create separate factions of "Africans" and "Arabs" in the western area of Darfur, a difficult task as the population were substantially intermarried and could not be distinguished by skin tone. This internal political instability was aggravated by cross-border conflicts with Chad and Libya[91] and the 1984–1985 Darfur famine.[92] In 2003, the Justice and Equality Movement and the Sudanese Liberation Army –accusing the government of neglecting Darfur and oppressing non-Arabs in favor of Arabs – began an armed insurgency.[93]

Estimates vary of the number of deaths resulting from attacks on the non-Arab/Arabized population by the Janjaweed militia: the Sudanese government claim that up to 10,000 have been killed in this conflict; the United Nations reported that about 300,000 had died as of 2010,[12] and other reports place the figures at between 200,000 and 400,000.[11] During an interview with David Frost for the Al Jazeera English programme Frost Over The World in June 2008, al-Bashir insisted that no more than 10,000 had died in Darfur.[94]

The Sudanese government had been accused of suppressing information by jailing and killing witnesses since 2004, and tampering with evidence, such as covering up mass graves.[95][96][97] The Sudanese government has also arrested and harassed journalists, thus limiting the extent of press coverage of the situation in Darfur.[98][99][100][101] While the United States government has described the conflict as genocide,[102] the UN has not recognized the conflict as such.[103] (see List of declarations of genocide in Darfur)

The United States Government stated in September 2004 "that genocide has been committed in Darfur and that the Government of Sudan and the Janjaweed bear responsibility and that genocide may still be occurring".[104] On 29 June 2004, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell met with al-Bashir in Sudan and urged him to make peace with the rebels, end the crisis, and lift restrictions on the delivery of humanitarian aid to Darfur.[105] Kofi Annan met with al-Bashir three days later and demanded that he disarm the Janjaweed.[106]

After fighting stopped in July and August, on 31 August 2006, the United Nations Security Council had approved Resolution 1706 which called for a new UN peacekeeping force consisting of 17,300 military personnel and 3,300 civilians[107] and named the United Nations–African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID).[108] It was intended to have supplanted or supplemented a 7,000-troop African Union Mission in Sudan peacekeeping force.[109] Sudan strongly objected to the resolution and said that it would see the UN forces in the region as "foreign invaders".[110] A day after rejecting the UN forces into Sudan, the Sudanese military launched a major offensive in the region.[111] In March 2007, the United Nations Human Rights Council accused Sudan's government of taking part in "gross violations" in Darfur[112] and urged the international community to take urgent action to protect people in Darfur.[113] A high-level technical consultation was held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on 11–12 June 2007, pursuant to the 4 June 2007 letters of the secretary-general and the chairperson of the African Union Commission, which were addressed to al-Bashir.[114] The technical consultations were attended by delegations from the Government of Sudan, the African Union, and the United Nations.[115][116]

In 2009, General Martin Luther Agwai, head of the UNAMID, said the war was over in the region, although low-level disputes remained. "Banditry, localised issues, people trying to resolve issues over water and land at a local level. But real war as such, I think we are over that," he said.[117] This perspective is contradicted by reports which indicate that violence continues in Darfur while peace efforts have been stalled repeatedly. Violence between Sudan's military and rebel fighters has beset South Kordofan and Blue Nile states since disputed state elections in May 2011, an ongoing humanitarian crisis that has prompted international condemnation and U.S. congressional hearings. In 2012, tensions between Sudan and South Sudan reached a boiling point when the Sudanese military bombed territory in South Sudan, leading to hostilities over the disputed Heglig (or Panthou) oil fields located along the Sudan-South Sudan border.[118] Omar al-Bashir sought the assistance of numerous non-western countries after the West, led by America, imposed sanctions against him, he said: "From the first day, our policy was clear: To look eastward, toward China, Malaysia, India, Pakistan, Indonesia, and even Korea and Japan, even if the Western influence upon some [of these] countries is strong. We believe that the Chinese expansion was natural because it filled the space left by Western governments, the United States, and international funding agencies. The success of the Sudanese experiment in dealing with China without political conditions or pressures encouraged other African countries to look toward China."[119]

Chadian President Idriss Déby visited Khartoum in 2010 and Chad kicked out the Darfuri rebels it had previously supported. Both Sudanese and Chadian sides together established a joint military border patrol.[120]

On 26 October 2011, al-Bashir said that Sudan gave military support to the Libyan rebels, who overthrew Muammar Gaddafi. In a speech broadcast live on state television, al-Bashir said the move was in response to Gaddafi's support for Sudanese rebels three years ago. Sudan and Libya have had a complicated and frequently antagonistic relationship for many years. President al-Bashir said the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), a Darfuri rebel group, had attacked Khartoum three years ago using Libyan trucks, equipment, arms, ammunition and money. He said God had given Sudan a chance to respond, by sending arms, ammunition and humanitarian support to the Libyan revolutionaries. "Our God, high and exalted, from above the seven skies, gave us the opportunity to reciprocate the visit," he said. "The forces which entered Tripoli, part of their arms and capabilities, were 100% Sudanese," he told the crowd. His speech was well received by a large crowd in the eastern Sudanese town of Kassala. But the easy availability of weapons in Libya, and that country's poorly guarded border with Darfur, are also of great concern to the Sudanese authorities.[121]

Al-Bashir in his speech said that his government's priority was to end the armed rebellion and tribal conflicts in order to save blood and direct the energies of young people towards building Sudan instead of "killing and destruction". He called upon youth of the rebel groups to lay down arms and join efforts to build the country.[122] Al Bashir sees himself as a man wronged and misunderstood. He takes full responsibility for the conflict in Darfur, he says, but says that his government did not start the fighting and has done everything in its power to end it.[25]

Al Bashir had signed two peace agreements for Darfur:

- The 2006 Darfur Peace Agreement, also known as the "Abuja Agreement", was signed on 5 May 2006[123] by the government of Sudan along with a faction of the SLA led by Minni Minnawi. However, the agreement was rejected by two other, smaller groups, the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) and a rival faction of the SLA led by Abdul Wahid al Nur.[124][125]

- The 2011 Darfur Peace Agreement, also known as the "Doha Agreement", was signed in July 2011 between the government of Sudan and the Liberation and Justice Movement. This agreement established a compensation fund for victims of the Darfur conflict, allowed the president of Sudan to appoint a vice-president from Darfur, and established a new Darfur Regional Authority to oversee the region until a referendum can determine its permanent status within the Republic of Sudan.[126]

The agreement also provided for power sharing at the national level: movements that sign the agreement will be entitled to nominate two ministers and two four ministers of state at the federal level and will be able to nominate 20 members to the national legislature. The movements will be entitled to nominate two state governors in the Darfur region.[127]

Indictment by the ICC

[edit]

On 14 July 2008, the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Luis Moreno Ocampo, alleged that al-Bashir bore individual criminal responsibility for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes that had been committed in Darfur since 2003. The prosecutor accused al-Bashir of having "masterminded and implemented" a plan to destroy the three main ethnic groups—Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa—with a campaign of murder, rape, and deportation.[22][128] The arrest warrant is supported by NATO, the Genocide Intervention Network, and Amnesty International.[129]

An arrest warrant for al-Bashir was issued on 4 March 2009 by a pre-trial chamber composed of judges Akua Kuenyehia of Ghana, Anita Usacka of Latvia, and Sylvia Steiner of Brazil[130] indicting him on five counts of crimes against humanity (murder, extermination, forcible transfer, torture and rape) and two counts of war crimes (pillaging and intentionally directing attacks against civilians).[23][131] The court ruled that there was insufficient evidence to prosecute him for genocide.[24][132] However, Usacka wrote a dissenting opinion arguing that there were "reasonable grounds to believe that Omar Al Bashir has committed the crime of genocide".[132]

Sudan is not a state party to the Rome Statute establishing the ICC, and thus claims that it does not have to execute the warrant. However, United Nations Security Council Resolution 1593 (2005) referred Sudan to the ICC, which gives the court jurisdiction over international crimes committed in Sudan and obligates Government of Sudan to cooperate with the ICC,[133] and therefore the court, Amnesty International and others insist that Sudan must comply with the arrest warrant of the International Criminal Court.[24][134] Amnesty International stated that al-Bashir must turn himself in to face the charges, and that the Sudanese authorities must detain him and turn him over to the ICC if he refuses.[135]

Al-Bashir was the first sitting head of state ever indicted by the ICC.[24] However, the Arab League[136] and the African Union condemned the warrant. Following the indictment Al-Bashir visited China,[137] Djibouti,[138][139] Egypt, Ethiopia, India,[140] Libya,[141][142] Nigeria,[143] Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and several other countries, all of which refused to have him arrested. ICC member state Chad also refused to arrest al-Bashir during a state visit in July 2010.[144] He was also invited to attend conferences in Denmark[145] and Turkey.[146] On 28 November 2011, following a visit to Kenya, Kenya's High Court Judge Nicholas Ombija ordered the Minister of Internal Security to arrest al-Bashir, "should he set foot in Kenya in the future".[147] In June 2015, while in South Africa for an African Union meeting, al-Bashir was prohibited from leaving that country while a court decided whether he should be handed over to the ICC for war crimes.[148] He, nevertheless, was allowed to leave South Africa soon afterward.[149] Luis Moreno Ocampo and Amnesty International claimed that al-Bashir's plane could be intercepted in International Airspace. Sudan announced that the presidential plane would always be escorted by fighter jets of the Sudanese Air Force to prevent his arrest. In March 2009, just before al-Bashir's visit to Qatar, the Sudanese government was reportedly considering sending fighter jets to accompany his plane to Qatar, possibly in response to France expressing support for an operation to intercept his plane in international airspace, as France has military bases in Djibouti and the United Arab Emirates.[150]

The charges against al-Bashir have been criticized and ignored in Sudan and abroad, particularly in Africa and the Muslim world. Former president of the African Union Muammar al-Gaddafi characterized the indictment as a form of terrorism. He also believed that the warrant is an attempt "by (the west) to recolonize their former colonies".[151] Egypt said, it was "greatly disturbed" by the ICC decision and called for an emergency meeting of the UN security council to defer the arrest warrant.[152] The Arab League Secretary-General Amr Moussa expressed that the organization emphasizes its solidarity with Sudan and condemned the warrant for "undermining the unity and stability of Sudan".[153] The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation denounced the warrant as unwarranted and totally unacceptable. It argued that the warrant demonstrated "selectivity and double standard applied in relation to issues of war crimes".[154] There have been large demonstrations by Sudanese people supporting President Bashir and opposing the ICC charges.[155]

Al-Bashir has rejected the charges, saying "Whoever has visited Darfur, met officials and discovered their ethnicities and tribes ... will know that all of these things are lies."[156] He described the charges as "not worth the ink they are written in".[157] The warrant was to be delivered to the Sudanese government, which stated that they would not carry it out.[24][133][134]

The Sudanese government retaliated against the warrant by expelling a number of international aid agencies, including Oxfam and Mercy Corps.[158] President Bashir described the aid agencies as thieves who take "99 percent of the budget for humanitarian work themselves, giving the people of Darfur 1 percent" and as spies in the work of foreign regimes. Bashir promised that national agencies will provide aid to Darfur.[159]

Al-Bashir was one of the candidates in the 2010 Sudanese presidential election, the first democratic election with multiple political parties participating since the 1986 election.[160][161] It had been suggested that by holding and winning a legitimate presidential elections in 2010, al-Bashir had hoped to evade the ICC's warrant for his arrest.[162] On 26 April, he was officially declared the winner after Sudan's election commission announced he had received 68% of the votes cast in the election.[163] However, The New York Times noted the voting was "marred by boycotts and reports of intimidation and widespread fraud".[164]

In August 2013, Bashir's plane was blocked from entering Saudi Arabian airspace when Bashir was attempting to attend the inauguration of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani,[165] whose country is the main supplier of weapons to Sudan.[166]

A second arrest warrant for al-Bashir was issued on 12 July 2010. The ICC issued an additional warrant adding 3 counts of genocide for the ethnic cleansing of the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa tribes.[139] The new warrant included the court's conclusion that there were reasonable grounds to suspect that al-Bashir acted with specific intent to destroy in part the Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa ethnic groups in the Darfur region.[167] The charges against al-Bashir, in three separate counts, include "genocide by killing", "genocide by causing serious bodily or mental harm" and "genocide by deliberately inflicting on each target group conditions of life calculated to bring about the group's physical destruction".[168] The new warrant acted as a supplement to the first, whereby the charges initially brought against al-Bashir all remained in place, but now included the crime of genocide which was initially ruled out, pending appeal.[169]

Al-Bashir said that Sudan is not a party to the ICC treaty and could not be expected to abide by its provisions just like the United States, China and Russia. He said "It is a political issue and double standards, because there are obvious crimes like Palestine, Iraq and Afghanistan, but [they] did not find their way to the International Criminal Court". He added "The same decision in which [the] Darfur case [was] being transferred to the court stated that the American soldiers [in Iraq and Afghanistan] would not be questioned by the court, so it is not about justice, it is a political issue." Al Bashir accused Luis Moreno Ocampo, the ICC's chief prosecutor since 2003 of repeatedly lying in order to damage his reputation and standing. Al-Bashir said "The behavior of the prosecutor of the court, it was clearly the behavior of a political activist not a legal professional. He is now working on a big campaign to add more lies." He added, "The biggest lie was when he said I have $9bn in one of the British banks, and thank God, the British bank and the [British] finance minister … denied these allegations." He also said: "The clearest cases in the world such as Palestine and Iraq and Afghanistan, clear crimes to the whole humanity – all were not transferred to the court."[25]

In October 2013, several members of the African Union expressed anger at the ICC, calling it "racist" for failing to file charges against Western leaders or Western allies while prosecuting only African suspects so far. The African Union demanded that the ICC protect African heads of state from prosecution.[170]

Military intervention in Yemen

[edit]In 2015, Sudan participated in the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Shia Houthis and forces loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh,[171] who was deposed during the 2011–2012 Yemeni Revolution.[172] Reuters reported that "The war in Yemen has given Omar Hassan al-Bashir, a skilled political operator who has ruled Sudan for a quarter-century, an opportunity to show wealthy Sunni powers that he can be an asset against Iranian influence – if the price is right."[173]

Allegations of corruption

[edit]During the Second Sudanese Civil War, Al-Bashir allegedly looted Sudan of much of its wealth. According to leaked US diplomatic cables, $9 billion of his siphoned wealth was stored in banks in London. Luis Moreno-Ocampo, the chief prosecutor of the ICC, stated that some of the funds were being held in the partially nationalized Lloyds Banking Group. He also reportedly told US officials it was necessary to go public with the scale of al-Bashir's extortion to turn public opinion against him.[174] One US official stated "Ocampo suggested if Bashir's stash of money were disclosed (he put the figure at $9bn), it would change Sudanese public opinion from him being a 'crusader' to that of a thief." "Ocampo reported Lloyd's bank in London may be holding or knowledgeable of the whereabouts of his money," the report says. "Ocampo suggested exposing Bashir had illegal accounts would be enough to turn the Sudanese against him."[175] A leaked diplomatic cable allegedly reveals that the Sudanese president had embezzled US$9 billion in state funds, but Lloyds Bank "insisted it was not aware of any link with Bashir," while a Sudanese government spokesman called the claim "ludicrous" and attacked the motives of the prosecutor.[176] In an interview with the Guardian, al-Bashir said, referring to ICC Prosecutor Ocampo, "The biggest lie was when he said I have $9 billion in one of the British banks, and thank God, the British bank and the [British] finance minister ... denied these allegations."[25] The arrest warrant actively increased public support for al-Bashir in Sudan.[177]

Part of the $8.9 billion fine the BNP Paribas paid for sanctions violations was related to their trade with Sudan. While smaller fines have also been given to other banks,[178] US Justice Department officials said that they found the BNP particularly uncooperative, calling it Sudan's de facto central bank.[179]

African space agency

[edit]In 2012, al-Bashir proposed setting up a continent-wide space agency in Africa. In a statement he said, "I'm calling for the biggest project, an African space agency. Africa must have its space agency... [It] will liberate Africa from technological domination".[180] This followed previous calls in 2010 by the African Union (AU) to conduct a feasibility study that would draw up a "road map for the creation of the African space agency". African astronomy received a massive boost when South Africa was awarded the majority shares of the Square Kilometre Array, the world's biggest radio telescope. It will see dishes erected in nine African countries. But skeptics have questioned whether a continental body in the style of NASA or the European Space Agency would be affordable.[180]

Ousting from power

[edit]On 11 April 2019, al-Bashir was removed from his post by the Sudanese Armed Forces[181] after many months of protests and civil uprisings.[182] He was immediately placed under house arrest pending the formation of a transitional council.[183] At the time of his arrest al-Bashir had been the longest-serving leader of Sudan since the country gained independence in 1956, and was the longest-ruling president of the Arab League. The army also ordered the arrest of all ministers in al-Bashir's cabinet, dissolved the National Legislature and formed a Transitional Military Council, led by his own First Vice President and Defense Minister, Lieutenant General Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf.[181]

Post-presidency

[edit]On 17 April 2019, al-Bashir was moved from house arrest to Khartoum's Kobar Prison.[184] On 13 May 2019, prosecutors charged al-Bashir with "inciting and participating in" the killing of protesters.[185] A trial for corruption (after $130 million was found in his home)[186] and money laundering against al-Bashir started during the following months.[30] On 14 December 2019, he was convicted for money laundering and corruption. He was sentenced to two years in prison.[187]

On 21 July 2020, his trial regarding the coup that brought him to power started. About 20 military personnel were indicted for their roles in the coup.[33] On 20 December 2022, al-Bashir said that he bears full responsibility for the events that took place in the country on June 30, 1989.[188] The trial is expected to continue for several more months and if convicted, Bashir could face a death sentence.[189]

International Criminal Court

[edit]On 5 November 2019, the Forces of Freedom and Change alliance (FFC), which holds indirect political power during the 39-month Sudanese transition to democracy, stated that it had reached a consensus decision in favor of transferring al-Bashir to the ICC after the completion of his corruption and money laundering trial.[30] In the following days, Sudanese transition period Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and Sovereignty Council member Siddiq Tawer stated that al-Bashir would be transferred to the ICC.[31][32] On 11 February 2020, Sudan's ruling military council agreed to hand over the ousted al-Bashir to the ICC in The Hague to face charges of crimes against humanity in Darfur.[190] In October 2020, ICC Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda and a delegation arrived in Sudan to discuss with the government about Bashir's indictment. In a deal with Darfurian rebels, the government agreed to set up a special war crimes court that would include Bashir.[191]

Detention

[edit]On 26 April 2023, the Sudanese Armed Forces stated that al-Bashir, Bakri Hassan Saleh, Abdel Rahim Mohammed Hussein and two other former officials were taken from Kobar Prison to Alia Military Hospital in Omdurman due to the conflict that erupted earlier that month.[192][193]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of State.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of State.

- ^ "Sudan's Omar Al-Bashir attends Mid-East's Largest Arms Fair". BBC News. 1 March 2015. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Sudan coup: Why Omar al-Bashir was overthrown". BBC News. 15 April 2019. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Alsaafin, Linah (24 August 2019). "Omar al-Bashir on trial: Will justice be delivered?". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Omar al-Bashir: Sudan ex-leader sentenced for corruption". BBC News. 14 December 2019. Archived from the original on 14 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ a b "FACTBOX – Sudan's President Omar Hassan al-Bashir". Reuters. 14 July 2008. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ a b "Dream election result for Sudan's President Bashir". BBC News. 27 April 2010. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Eliza Mackintosh; James Griffiths (11 April 2019). "Sudan's government has been dissolved". CNN. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "Genocide in Darfur". United Human Rights Council. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Magdy, Samy (11 February 2020). "Official: Sudan to hand over al-Bashir for genocide trial". AP News. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "South Sudan profile". BBC News. 5 July 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Death toll disputed in Darfur". NBC News. 28 March 2008. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Q&A: Sudan's Darfur conflict". BBC News. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Africa :: Sudan — The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 2 November 2021. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Darfur peace talks to resume in Abuja on Tuesday: AU". People's Daily Online. Archived from the original on 30 November 2005. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Hundreds Killed in Attacks in Eastern Chad". The Washington Post. 11 April 2007. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ Alfred de Montesquiou (16 October 2006). "AUF Ineffective, Complain Refugees in Darfur". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ Darfur – overview Archived 11 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, unicef.org.

- ^ "Sudan cuts Chad ties over attack". BBC News. 11 May 2008. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ Copnall, James (26 November 2011). "Sudan armed Libyan rebels, says President Bashir". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ "Libya leader thanks Sudan for weapons that helped former rebels oust Gadhafi". Haaretz. Reuters. 26 November 2011. Archived from the original on 20 November 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ "Sudan: Country Studies". Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. 22 March 2011. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ a b International Criminal Court (14 July 2008). "ICC Prosecutor presents case against Sudanese President, Hassan Ahmad AL BASHIR, for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes in Darfur". Archived from the original on 25 August 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ a b International Criminal Court (4 March 2009). "Warrant of Arrest for Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2009. (358 KB). Retrieved on 4 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f "Warrant issued for Sudan's Bashir". BBC News. 4 March 2009. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d Simon Tisdall (20 April 2011). "Omar al-Bashir: genocidal mastermind or bringer of peace?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ HENRY OWUOR in Khartoum (5 March 2009). "After Bashir warrant, Sudan united in protest". Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "International Criminal Court Cases in Africa: Status and Policy Issues" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ Abdelaziz, Khalid; Abdelaty, Ali; El Sherif, Mohamed; Saba, Yousef; Nichols, Michelle; Aboudi, Sami; Lewis, Aidan (11 April 2019). "Sudan's Bashir Forced to Step Down". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ Hassan, Mai; Kodouda, Ahmed (11 October 2019). "Sudan's Uprising: The Fall of a Dictator". Journal of Democracy. 30 (4): 89–103. doi:10.1353/jod.2019.0071. ISSN 1086-3214.

- ^ a b c "Sudan's Forces for Freedom and Change: 'Hand Al Bashir to ICC'". Radio Dabanga. 5 November 2019. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ a b "الوساطة تسلم مقترحات جديدة حول النقاط العالقة في وثيقة سلام دارفور Sudan's PM says al-Bashir to be handed over to the ICC" [Mediation receives new proposals on sticking points in the Darfur Peace Document]. Sudan Tribune. 5 November 2019. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ a b "اجواء مشحونة تخيم على ابيى بعد اشتباكات دامية بين الدينكا والمسيرية" [A charged atmosphere hangs over Abyei after bloody clashes between the Dinka and the Misseriya]. Sudan Tribune. 8 November 2019. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Sudan's ex-President Bashir on trial for 1989 coup". BBC News. 21 July 2020. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "The Prosecutor v. Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir" (PDF). International Criminal Court. July 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2023.

- ^ "البشير يحضر جنازة والدته وسط حراسة أمنية مشددة" [Al-Bashir attends his mother's funeral amid tight security]. صفحة أولى. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "البشير يحضر مراسم دفن والدته.. وجدل على 'تويتر'" [Al-Bashir attends his mother's burial ceremony ... and controversy on Twitter]. السودان نيوز 365. 30 July 2019. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "البشير يحضر مراسم دفن والدته" [Al-Bashir attending his mother's burial ceremony]. 30 July 2019. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ Fanack (12 February 2020). "الرئيس عمر البشير" [President Omar al-Bashir]. وقائع الشرق الأوسط وشمال أفريقيا (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ "وفاة خال البشير... أبرز خصوم جنوب السودان" [The death of Al-Bashir's uncle... the most prominent opponent of South Sudan]. Asharq Al-Awsat (in Arabic). 16 May 2021. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b Moorcraft, Paul (30 April 2015). Omar Al-Bashir and Africa's Longest War. United Kingdom: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 9781473854963. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Omar al-Bashir: Sudan's ousted president". BBC. 14 August 2019. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Fred Bridgland (14 July 2008). "President Bashir, you are hereby charged..." The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ "Profile: Omar al-Bashir". Archived from the original on 24 December 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ "Example of Section Blog layout (FAQ section)". 17 April 2014. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014.

- ^ Bekele, Yilma (12 July 2008). "Chickens are coming home to roost!". Ethiopian Review. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Cowell, Alan (1 July 1989). "Military Coup in Sudan Ousts Civilian Regime". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad (2002), p.181

- ^ Walker, Peter (14 July 2008). "Profile: Omar al-Bashir". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ a b New York Times, 16 March 1996, p.4

- ^ The Appendix of the 9/11 Commission Report

- ^ Stefano Bellucci, "Islam and Democracy: The 1999 Palace Coup", Middle East Policy 7, no. 3 (June 2000):168

- ^ "Sudan Government 2001 – Flags, Maps, Economy, Geography, Climate, Natural Resources, Current Issues, International Agreements, Population, Social Statistics, Political System". Workmall.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Sudan president wins re-election". Al Jazeera. 27 April 2010. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ "IFES Election Guide | Country Profile: Sudan". Electionguide.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ a b Gettleman, Jeffrey (24 October 2006). "War in Sudan? Not Where the Oil Wealth Flows". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Sudan". Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Shahzad (23 February 2002). "Bin Laden uses Iraq to plot new attacks". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2002. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Families of USS Cole Victims Sue Sudan for $105 Million". Fox News. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Bin Laden uses Iraq to plot new attacks". atimes.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2002.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Spetalnick, Matt (7 October 2017). "U.S. lifts Sudan sanctions, wins commitment against arms deals with North Korea". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ Risen, James (27 October 1999). "To Bomb Sudan Plant, or Not: A Year Later, Debates Rankle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 October 2002. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Profile: Sudan's President Bashir". BBC News. 25 November 2003. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ Fuller, The Future of Political Islam, (2003), p.111

- ^ Wright, The Looming Tower, (2006), pp.221–3

- ^ Wasil Ali, "Sudanese Islamist opposition leader denies link with Darfur rebels" Archived 12 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Sudan Tribune, 13 May 2008.

- ^ "Profile: Sudan's Islamist leader". BBC. 15 January 2009. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Lansford, Tom (19 March 2019). Political Handbook of the World 2018–2019. CQ Press. ISBN 978-1-5443-2713-6. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ "Head of opposition backs ICC's arrest warrant for Bashir". France 24. AFP. 9 March 2009. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Middleton, Drew (4 October 1982). "Sudanese Brigades Could Provide Key Aid for Iraq; Military Analysis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Perlez, Jane (26 August 1998). "After the Attacks: The Connection; Iraqi Deal with Sudan on Nerve Gas Is Reported". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "U.S. – Sudan Relations". U.S. Embassy in Sudan. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Carlos the Jackal Reportedly Arrested During Liposuction". Los Angeles Times. 21 August 1994. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "1996 CIA Memo to Sudanese Official". The Washington Post. 3 October 2001. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "The Osama Files". Vanity Fair. January 2002. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Sudan Expels Bin Laden". History Commons. 18 May 1996. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Carney, Timothy; Mansoor Ijaz (30 June 2002). "Intelligence Failure? Let's Go Back to Sudan". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ "Democratic Fundraiser Pursues Agenda on Sudan". The Washington Post. 29 April 1997. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014.

- ^ Ijaz, Mansoor (30 September 1998). "Olive Branch Ignored". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Carney, Timothy; Ijaz, Mansoor (30 June 2002). "Intelligence Failure? Let's Go Back to Sudan". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Malik, Mohamed; Malik, Malik (18 March 2015). "The Efficacy of United States Sanctions on the Republic of Sudan". Journal of Georgetown University-Qatar Middle Eastern Studies Student Association. 2015 (1): 3. doi:10.5339/messa.2015.7. ISSN 2311-8148.

- ^ McIntyre, Jamie; Koppel, Andrea (21 August 1998). "Pakistan lodges protest over U.S. missile strikes". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Miniter, Richard (1 August 2003). Losing Bin Laden: How Bill Clinton's Failures Unleashed Global Terror. Regnery Publishing. pp. 114, 140. ISBN 978-0-89526-074-1.

- ^ Wong, Edward (4 December 2019). "Trump Administration Moves to Upgrade Diplomatic Ties With Sudan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ "Omar al-Bashir to speak at UN Summit in New York". Eyewitness News. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "The U.S. Committee for Refugees Crisis in Sudan". Archived from the original on 10 December 2004.

- ^ Morrison, J. Stephen; de Waal, Alex (1 March 2005). "Can Sudan Escape its Intractability?". In Crocker, Chester A.; Hampson, Fen Osler; Aall, Pamela (eds.). Grasping the Nettle: Analyzing Cases of Intractable Conflict. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace. p. 162. ISBN 978-1929223602.

- ^ "Sudan bids rebel leader farewell". BBC News. 6 August 2005. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Peace prospects in Sudan". IRIN. 12 February 2004. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ "Sudanese flesh out final deal". BBC News. 7 October 2004. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey (9 July 2011). "After Years of Struggle, South Sudan Becomes a New Nation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 19 October 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Prunier, G., The Ambiguous Genocide, Ithaca, NY, 2005, pp. 42–44

- ^ Prunier, pp. 47–52

- ^ Pilling, David (11 April 2019). "Bashir: Sudan's autocrat turned pariah leaves ruptured country". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Frost Over the World – Darfur special". Al Jazeera. 21 September 2008. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Grave, A Mass (28 May 2007). "The horrors of Darfur's ground zero". The Australian. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ^ "Darfur Destroyed – Summary". Human Rights Watch. 7 May 2004. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Darfur Destroyed – Destroying Evidence?". Human Rights Watch. June 2004. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Country of Origin Report: Sudan" (PDF). Research, Development and Statistics (RDS), Home Office, UK. 27 October 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ^ "Tribune correspondent charged as spy in Sudan". Los Angeles Times. 26 August 2006. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006.

- ^ "World Press Freedom Review". International Press Institute. 2005. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009.

- ^ Beeston, Richard (12 August 2004). "Police put on a show of force, but are Darfur's militia killers free to roam?". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Darfur: A 'Plan B' to Stop Genocide?". US Department of State. 11 April 2007. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ Report of the International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur to the United Nations Secretary-General (PDF) Archived 1 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations, 25 January 2005

- ^ Kessler, Glenn; Lynch, Colum (10 September 2004). "U.S. Calls Killings in Sudan Genocide". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Marquis, Christopher (30 June 2004). "Powell to Press Sudan to Ease the Way for Aid in Darfur". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Elgabir, Nima (2 July 2004). "Sudan rejects 30-day deadline". Independent Online. Retrieved 15 July 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Sudan warms to Darfur force plan". CNN. 17 November 2006. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Bonkoungou, Mathieu; Bavier, Joe (5 November 2016). Evans, Catherine (ed.). "Burkina Faso to withdraw Darfur peacekeepers by July". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "U.N. OKs 26,000 Darfur Peacekeepers". CBS News. Associated Press. 31 July 2007. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Weiss, Thomas G. (20 May 2013). What's Wrong with the United Nations and How to Fix it. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7456-6146-9. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Sudan reported to launch new offensive in Darfur". Canana.com. Associated Press. 1 September 2006. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Muller, Joachim; Sauvant, Karl P. (2011). Annual Review of United Nations Affairs 2009/2010. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. xxii. ISBN 978-0-19-975911-8. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Waddington, Richard (12 March 2007). "Sudan orchestrated Darfur crimes, U.N. mission says". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "Conclusions of the high-level AU UN consultations with the Government of Sudan on the Hybrid Operation". African Union. 12 July 2007. Archived from the original on 25 October 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Lederer, Edith M. (12 June 2007). "Sudan accepts plan for joint peacekeeping force for Darfur". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ "Sudanese president answers questions on Darfur". Finalcall.com. 14 May 2007. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ "War in Sudan's Darfur 'is over'". BBC News. 27 August 2009. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ^ "Sudan – NDI". Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Sam Dealey (14 August 2009). "Omar al-Bashir Q&A: 'In Any War, Mistakes Happen on the Ground'". Time. Archived from the original on 18 August 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ "Sudan, Chad agree to end proxy wars". Mail & Guardian. 9 February 2010. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ "Sudan armed Libyan rebels, says President Bashir". BBC News. 26 October 2011. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ "Bashir vows to end rebellion and tribal clashes before 2015 elections". Sudan Tribune. 28 March 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ United Nations. "UNAMID Background". Archived from the original on 6 November 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Peace Agreements, Sudan, Darfur Peace Agreement". Conflict Encyclopedia. Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Kessler, Glenn; Wax, Emily (5 May 2006). "Sudan, Main Rebel Group Sign Peace Deal". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ Darfur Peace Document (PDF), 27 April 2011, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2018, retrieved 4 February 2014

- ^ "Signing of Doha Agreement prompts mixed reactions". Radio Dabanga. 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013.

- ^ Simons, Marlise; Polgreen, Lydia (14 July 2008). "Hague court accuses Sudanese president of genocide". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Abomo, Paul Tang (22 May 2018). R2P and the US Intervention in Libya. Springer. p. 25. ISBN 978-3-319-78831-9. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ (Official Channel of the ICC) on YouTube

- ^ "ICC issues a warrant of arrest for Omar Al Bashir, President of Sudan". International Criminal Court. 4 March 2009. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ a b International Criminal Court (4 March 2009). "Decision on the Prosecution's Application for a Warrant of Arrest against Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2009. (7.62 MB). Retrieved on 4 March 2009

- ^ a b Amnesty International – Document – Sudan: Amnesty International calls for arrest of President Al Bashir. 4 March 2009

- ^ a b "Sudan ICC charges concern Mbeki". BBC News. 27 July 2008. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ "Everything you need to know about human rights. – Amnesty International". Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Arab leaders back 'wanted' Bashir". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ^ sda/ddp/afp/dpa (29 June 2011). "Peking empfängt al-Bashir wie einen Ehrengast". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "ICC Suspect Al-Bashir Travels to Djibouti". Coalition for the International Criminal Court. 9 May 2011. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "BashirWatch". United to End Genocide. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "India-Africa summit: Arrest Sudan President Omar al-Bashir, demands Amnesty International". The Indian Express. New Delhi. 26 October 2015. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ "Sudan's Bashir offers help to Libya during criticised visit". BBC News. 7 January 2012. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Sudan president Bashir visits Libya". The Belfast Telegraph. 7 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ "Bashir leaves Nigeria amid calls for arrest". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 16 July 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ Rice, Xan (22 July 2010). "Chad refuses to arrest Omar al-Bashir on genocide charges". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ "Danish government must arrest Sudanese President if he attends climate conference". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Turkey: No to safe haven for fugitive from international justice". Amnesty International. 6 November 2009. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Kenyan court issues arrest order for Sudan's Bashir". Reuters. 28 November 2011. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Mataboge, Mmanaledi (14 June 2015). "SA court to rule on Sudan president's fate". Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 June 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "Laughter as court told Al-Bashir has left". News24. 15 June 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Elias Kifle (28 March 2009). "Fighter jets may guard al-Bashir's flight to Qatar". Ethiopian Review. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013.

- ^ "Sudan leader in Qatar for summit". BBC News. 29 March 2009. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ Rice, Xan (4 March 2009). "Uproar in Sudan over Bashir war crimes warrant". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ "Arab leaders snub al-Bashir warrant". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ "The Organization of the Islamic Conference". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ "Arrest warrant against al-Bashir triggers int'l concern_English_Xinhua". Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Thomasson, Emma (14 July 2008). "ICC prosecutor seeks arrest of Sudan's Bashir". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ "IRIN Africa – SUDAN: The case against Bashir – Sudan – Conflict – Human Rights – Refugees/IDPs". IRIN. 4 March 2009. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ "Sudan orders aid agency expulsions". CNN. 4 March 2009. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Sudan: We will fill the aid gaps, government insists". Refworld. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "SPLM Kiir to run for president in Sudan 2009 elections". Sudan Tribune. 26 July 2008. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Eastern Sudan Beja, SPLM discuss electoral alliance". Sudan Tribune. 28 July 2008. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Sudan's al-Bashir wins landmark presidential poll". France 24. 26 April 2010. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "President Omar al-Bashir declared winner of Sudan poll". BBC News. 26 April 2010. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (12 July 2010). "International Court Adds Genocide to Charges Against Sudan Leader". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ^ "Sudan President Blocked from Saudi Air Space". Voice of America. 4 August 2013. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ "Under Omar al-Bashir, Sudan is in steepening decline". The Economist. Khartoum. 1 February 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ RTTNews [1] Archived 24 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine 12 July 2010, accessed 12 July 2010

- ^ Morris, P Sean (February 2018). "Economic Genocide Under International Law". The Journal of Criminal Law. 82 (1): 29. doi:10.1177/0022018317749698. ISSN 0022-0183.

- ^ "Pre-Trial Chamber I issues a second warrant of arrest against Omar Al Bashir for counts of genocide". International Criminal Court. 12 July 2010. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Geoffrey York (13 October 2013). "African Union demands ICC exempt leaders from prosecution". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ "Sudan Joining Saudi Campaign in Yemen Shows Shift in Region Ties Archived 6 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Bloomberg. 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Saudi-led coalition strikes rebels in Yemen, inflaming tensions in region Archived 16 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine". CNN. 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Sudan maintains balancing act with Saudi, Iran Archived 1 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine". Reuters. 30 April 2015.

- ^ "Profile: Sudan's Omar al-Bashir". BBC. 5 December 2011. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Hirsch, Afua (17 December 2010). "WikiLeaks cables: Sudanese president 'stashed $9bn in UK banks". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ "Bank denies WikiLeaks' Sudan claim". Nuneaton-news. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ "Omer Hassan Ahmad Al-Bashir". Sudan Tribune. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Mohammed Amin (13 October 2019). "Bashir's billions and the banks that helped him: Sudan fights to recover stolen funds". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Nate Raymond (1 May 2015). "BNP Paribas sentenced in $8.9 billion accord over sanctions violations". Reuters. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

Authorities said that BNP essentially functioned as the "central bank for the government of Sudan," concealing its tracks and failing to cooperate when first contacted by law enforcement

- ^ a b David Smith (6 September 2012). "Sudanese president calls for African space agency". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ a b McKintosh, Eliza; Griffiths, James (11 April 2019). "Sudan's Omar al-Bashir forced out in coup". Cable News Network. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ "CNN News". Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Jubilation as Sudan's Omar Al-Bashir 'under house arrest now'". Arab News. 11 April 2019. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Sudan crisis: Ex-President Omar al-Bashir moved to prison". BBC News. 17 April 2019. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "Sudan's Omar al-Bashir charged over killing of protesters". Al Jazeera. 13 May 2019. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "Two years in a rest home for Sudan's former tyrant". The Economist. 18 December 2019. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ Dahir, Abdi Latif (13 December 2019). "Sudan's Ousted Leader Is Sentenced to Two Years for Corruption". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ "الرئيس السوداني المعزول عمر البشير: أتحمل المسؤولية عن أحداث 30 يونيو 1989 (فيديو)" [Deposed Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir: I bear responsibility for the events of June 30, 1989 (video)]. mubasher.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ "Sudan's Bashir admits role in 1989 coup during trial". Al Arabiya English. 20 December 2022. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ "Sudan signals it may send former dictator Omar al-Bashir to ICC". The Guardian. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "Omar Bashir: ICC delegation begins talks in Sudan over former leader". BBC News. 17 October 2020. Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Former Sudan Officials Leave Prison, Raising Questions about Bashir". VOA News. 26 April 2023. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023.