Appendicitis

| Appendicitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Epityphlitis[1] |

| |

| An acutely inflamed and enlarged appendix, sliced lengthwise. | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

| Symptoms | Periumbilical or right lower abdominal pain, vomiting, decreased appetite[2] |

| Complications | Abdominal inflammation, sepsis[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, medical imaging, blood tests[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Mesenteric adenitis, cholecystitis, psoas abscess, abdominal aortic aneurysm[5] |

| Treatment | Surgical removal of the appendix, antibiotics[6][7] |

| Frequency | 11.6 million (2015)[8] |

| Deaths | 50,100 (2015)[9] |

Appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix.[2] Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and decreased appetite.[2] However, approximately 40% of people do not have these typical symptoms.[2] Severe complications of a ruptured appendix include widespread, painful inflammation of the inner lining of the abdominal wall and sepsis.[3]

Appendicitis is primarily caused by a blockage of the hollow portion in the appendix.[10] This blockage typically results from a faecolith, a calcified "stone" made of feces.[6] Some studies show a correlation between appendicoliths and disease severity.[11] Other factors such as inflamed lymphoid tissue from a viral infection, intestinal parasites, gallstone, or tumors may also lead to this blockage.[6] When the appendix becomes blocked, it experiences increased pressure, reduced blood flow, and bacterial growth, resulting in inflammation.[6][12] This combination of factors causes tissue injury and, ultimately, tissue death.[13] If this process is left untreated, it can lead to the appendix rupturing, which releases bacteria into the abdominal cavity, potentially leading to severe complications.[13][14]

The diagnosis of appendicitis is largely based on the person's signs and symptoms.[12] In cases where the diagnosis is unclear, close observation, medical imaging, and laboratory tests can be helpful.[4] The two most commonly used imaging tests for diagnosing appendicitis are ultrasound and computed tomography (CT scan).[4] CT scan is more accurate than ultrasound in detecting acute appendicitis.[15] However, ultrasound may be preferred as the first imaging test in children and pregnant women because of the risks associated with radiation exposure from CT scans.[4] Although ultrasound may aid in diagnosis, its main role is in identifying important differentials, such as ovarian pathology in females or mesenteric adenitis in children.

The standard treatment for acute appendicitis involves the surgical removal of the inflamed appendix.[6][12] This procedure can be performed either through an open incision in the abdomen (laparotomy) or using minimally invasive techniques with small incisions and cameras (laparoscopy). Surgery is essential to reduce the risk of complications or potential death associated with the rupture of the appendix.[3] Antibiotics may be equally effective in certain cases of non-ruptured appendicitis.[16][7][17] It is one of the most common and significant causes of sudden abdominal pain. In 2015, approximately 11.6 million cases of appendicitis were reported, resulting in around 50,100 deaths worldwide.[8][9] In the United States, appendicitis is one of the most common causes of sudden abdominal pain requiring surgery.[2] Annually, more than 300,000 individuals in the United States undergo surgical removal of their appendix.[18]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

The presentation of acute appendicitis includes acute abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. As the appendix becomes more swollen and inflamed, it begins to irritate the adjoining abdominal wall. This leads the pain to localize at the right lower quadrant. This classic migration of pain may not appear in children under three years. This pain can be elicited through signs, which can feel sharp. Pain from appendicitis may begin as dull pain around the navel. After several hours, the pain usually migrates towards the right lower quadrant, where it becomes localized. Symptoms include localized findings in the right iliac fossa. The abdominal wall becomes very sensitive to gentle pressure (palpation). There is pain in the sudden release of deep tension in the lower abdomen (Blumberg's sign). If the appendix is retrocecal (localized behind the cecum), even deep pressure in the right lower quadrant may fail to elicit tenderness (silent appendix). This is because the cecum, distended with gas, protects the inflamed appendix from pressure. Similarly, if the appendix lies entirely within the pelvis, there is typically a complete absence of abdominal rigidity. In such cases, a digital rectal examination elicits tenderness in the rectovesical pouch. Coughing causes point tenderness in this area (McBurney's point), called Dunphy's sign.[medical citation needed]

Causes

[edit]

Acute appendicitis seems to be the result of a primary obstruction of the appendix.[19][10] Once this obstruction occurs, the appendix becomes filled with mucus and swells. This continued production of mucus leads to increased pressures within the lumen and the walls of the appendix. The increased pressure results in thrombosis and occlusion of the small vessels, and stasis of lymphatic flow. At this point, spontaneous recovery rarely occurs. As the occlusion of blood vessels progresses, the appendix becomes ischemic and then necrotic. As bacteria begin to leak out through the dying walls, pus forms within and around the appendix (suppuration). The result is appendiceal rupture (a 'burst appendix') causing peritonitis, which may lead to sepsis and in rare cases, death. These events are responsible for the slowly evolving abdominal pain and other commonly associated symptoms.[13]

The causative agents include bezoars, foreign bodies, trauma, lymphadenitis and, most commonly, calcified fecal deposits that are known as appendicoliths or fecaliths.[20][21] The occurrence of obstructing fecaliths has attracted attention since their presence in people with appendicitis is higher in developed than in developing countries.[22] In addition an appendiceal fecalith is commonly associated with complicated appendicitis.[23] Fecal stasis and arrest may play a role, as demonstrated by people with acute appendicitis having fewer bowel movements per week compared with healthy controls.[21][24]

The occurrence of a fecalith in the appendix was thought to be attributed to a right-sided fecal retention reservoir in the colon and a prolonged transit time. However, a prolonged transit time was not observed in subsequent studies.[25] Diverticular disease and adenomatous polyps was historically unknown and colon cancer was exceedingly rare in communities where appendicitis itself was rare or absent, such as various African communities. Studies have implicated a transition to a Western diet lower in fiber in rising frequencies of appendicitis as well as the other aforementioned colonic diseases in these communities.[26][27] And acute appendicitis has been shown to occur antecedent to cancer in the colon and rectum.[28] Several studies offer evidence that a low fiber intake is involved in the pathogenesis of appendicitis.[29][30][31] This low intake of dietary fiber is in accordance with the occurrence of a right-sided fecal reservoir and the fact that dietary fiber reduces transit time.[32]

Diagnosis

[edit]

The physician will ask questions to get the health history, assess the patient's symptoms, do a complete physical exam, and order both laboratory and imaging tests.[33] Appendicitis symptoms fall into two categories, typical and atypical.[34]

Typical appendicitis is characterized by a migratory right iliac fossa pain associated with nausea, and anorexia, which can occur with or without vomiting and localized muscle stiffness/ generalized guarding.[34] It is possible the pain could localize to the left lower quadrant in people with situs inversus totalis.[35] The combination of migrated umbilical pain to the right lower quadrant, loss of appetite for food, nausea, unsustained vomiting, and mild fever is classic.[34]

Atypical histories lack this typical progression and may include pain in the right lower quadrant as an initial symptom. Irritation of the peritoneum (inside lining of the abdominal wall) can lead to increased pain on movement, or jolting, for example going over speed bumps.[36] Atypical histories often require imaging with ultrasound or CT scanning.[3]

Signs

[edit]During the early stages of appendicitis diagnosis, it is common for physical exams to present inconspicuous findings. Signs of inflammation become noticeable as the disease progresses. These signs may include:[37]

- Aure-Rozanova's sign: Increased pain on palpation with a finger in the right inferior lumbar triangle (can be a positive Blumberg's sign).[38]

- Bartomier-Michelson's sign: Increased pain on palpation at the right iliac region as the person being examined lies on their left side compared to when they lie on their back.[38]

- Dunphy's sign: Increased pain in the right lower quadrant by coughing.[39]

- Hamburger sign: The patient refuses to eat (anorexia is 80% sensitive for appendicitis)[40]

- Kocher's sign (Kosher's sign): From the person's medical history, the start of pain in the umbilical region with a subsequent shift to the right iliac region.[38]

- Massouh's sign: Developed in and popular in southwest England, the examiner performs a firm swish with their index and middle finger across the abdomen from the xiphoid process to the left and the right iliac fossa.[39]

- Obturator sign: The person being evaluated lies on her or his back with the hip and knee both flexed at ninety degrees. The examiner holds the person's ankle with one hand and knee with the other hand. The examiner rotates the hip by moving the person's ankle away from their body while allowing the knee to move only inward. A positive test is pain with internal rotation of the hip.[41]

- Psoas sign, also known as "Obraztsova's sign", is right lower-quadrant pain that is produced with either the passive extension of the right hip or by the active flexion of the person's right hip while supine. The pain that is elicited is due to inflammation of the peritoneum overlying the iliopsoas muscles and inflammation of the psoas muscles themselves. Straightening out the leg causes pain because it stretches these muscles, while flexing the hip activates the iliopsoas and causes pain.[41]

- Rovsing's sign: Pain in the lower right abdominal quadrant with continuous deep palpation starting from the left iliac fossa upwards (counterclockwise along the colon). The thought is there will be increased pressure around the appendix by pushing bowel contents and air toward the ileocaecal valve provoking right-sided abdominal pain.[42]

- Rosenstein's sign (Sitkovsky's sign): Increased pain in the right iliac region as the person is being examined lies on their left side.[43]

- Perman's sign: In acute appendicitis palpation in the left iliac fossa may produce pain in the right iliac fossa.[44]

Laboratory tests

[edit]While there is no laboratory test specific for appendicitis, a complete blood count (CBC) is done to check for signs of infection or inflammation. Although 70–90 percent of people with appendicitis may have an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count, there are many other abdominal and pelvic conditions that can cause the WBC count to be elevated.[45] However, a high WBC count may not alone represent a solid indicator of appendicitis but rather an inflammation [15] but the neutrophil ratio was more sensitive and specific for acute appendicitis.[46]

In children, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) demonstrates a high degree of accuracy in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis and distinguishes complicated appendicitis from the simple one.[47] 75–78 percent of the patients have neutrophilia.[39] Delta-neutrophil index (DNI) is a valuable parameter that helps in the diagnosis of histologically normal appendicitis and distinguishing between simple and complicated appendicitis.[48]

A C-reactive protein (CRP) blood test will be ordered by the doctor to find out if there are any further causes of inflammation.[33] The C-reactive protein/albumin (CRP/ALB) ratio can be a reliable predictor of complicated appendicitis.[49]

The urinalysis is important for ruling out a urinary tract infection as the cause of abdominal pain. The presence of more than 20 WBC per high-power field in the urine is more suggestive of a urinary tract disorder.[45]

If the patient is a woman, a pregnancy test will be ordered.[33]

Imaging

[edit]In children, the clinical examination is important to determine which children with abdominal pain should receive immediate surgical consultation and which should receive diagnostic imaging.[50] Because of the health risks of exposing children to radiation, ultrasound is the preferred first choice with CT scan being a legitimate follow-up if the ultrasound is inconclusive.[51][52][53] CT scan is more accurate than ultrasound for the diagnosis of appendicitis in adults and adolescents. CT scan has a sensitivity of 94%, specificity of 95%. Ultrasonography had an overall sensitivity of 86%, a specificity of 81%.[54]

Ultrasound

[edit]

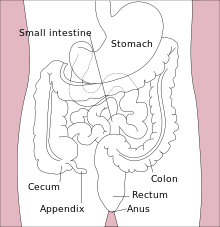

Abdominal ultrasonography, preferably with doppler sonography, is useful to detect appendicitis, especially in children. Ultrasound can show the free fluid collection in the right iliac fossa, along with a visible appendix with increased blood flow when using color Doppler, and noncompressibility of the appendix, as it is essentially walled-off abscess. Other secondary sonographic signs of acute appendicitis include the presence of echogenic mesenteric fat surrounding the appendix and the acoustic shadowing of an appendicolith.[55] In some cases (approximately 5%),[56] ultrasonography of the iliac fossa does not reveal any abnormalities despite the presence of appendicitis. This false-negative finding is especially true of early appendicitis before the appendix has become significantly distended. Also, false-negative findings are more common in adults where larger amounts of fat and bowel gas make visualizing the appendix technically difficult. Despite these limitations, sonographic imaging with experienced hands can often distinguish between appendicitis and other diseases with similar symptoms. Some of these conditions include inflammation of lymph nodes near the appendix or pain originating from other pelvic organs such as the ovaries or Fallopian tubes. Ultrasounds may be either done by the radiology department or by the emergency physician.[57]

-

Ultrasound showing appendicitis and an appendicolith[58]

-

Ultrasound showing appendicitis and an appendicolith[58]

-

Ultrasound of a normal appendix for comparison

-

A normal appendix without and with compression. Absence of compressibility indicates appendicitis.[55]

Computed tomography

[edit]

Where it is readily available, computed tomography (CT) has become frequently used, especially in people whose diagnosis is not obvious on history and physical examination. Although some concerns about interpretation are identified, a 2019 Cochrane review found that sensitivity and specificity of CT for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in adults was high.[59] Concerns about radiation tend to limit use of CT in pregnant women and in children, especially with the increasingly widespread usage of MRI.[60][61]

The accurate diagnosis of appendicitis is multi-tiered, with the size of the appendix having the strongest positive predictive value, while indirect features can either increase or decrease sensitivity and specificity. A size of over 6 mm is both 95% sensitive and specific for appendicitis.[62]

However, because the appendix can be filled with fecal material, causing intraluminal distention, this criterion has shown limited utility in more recent meta-analyses.[63] This is as opposed to ultrasound, in which the wall of the appendix can be more easily distinguished from intraluminal feces. In such scenarios, ancillary features such as increased wall enhancement as compared to adjacent bowel and inflammation of the surrounding fat, or fat stranding, can be supportive of the diagnosis. However, their absence does not preclude it. In severe cases with perforation, an adjacent phlegmon or abscess can be seen. Dense fluid layering in the pelvis can also result, related to either pus or enteric spillage. When patients are thin or younger, the relative absence of fat can make the appendix and surrounding fat stranding difficult to see.[63]

Magnetic resonance imaging

[edit]Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) use has become increasingly common for diagnosis of appendicitis in children and pregnant patients due to the radiation dosage that, while of nearly negligible risk in healthy adults, can be harmful to children or the developing baby.[64] In pregnancy, it is more useful during the second and third trimester, particularly as the enlargening uterus displaces the appendix, making it difficult to find by ultrasound. The periappendiceal stranding that is reflected on CT by fat stranding on MRI appears as an increased fluid signal on T2 weighted sequences. First trimester pregnancies are usually not candidates for MRI, as the fetus is still undergoing organogenesis, and there are no long-term studies to date regarding its potential risks or side effects.[65]

X-ray

[edit]

In general, plain abdominal radiography (PAR) is not useful in making the diagnosis of appendicitis and should not be routinely obtained from a person being evaluated for appendicitis.[66][67] Plain abdominal films may be useful for the detection of ureteral calculi, small bowel obstruction, or perforated ulcer, but these conditions are rarely confused with appendicitis.[68] An opaque fecalith can be identified in the right lower quadrant in fewer than 5% of people being evaluated for appendicitis.[45] A barium enema has proven to be a poor diagnostic tool for appendicitis. While failure of the appendix to fill during a barium enema has been associated with appendicitis, up to 20% of normal appendices do not fill.[68]

Scoring systems

[edit]Several scoring systems have been developed to try to identify people who are likely to have appendicitis. The performance of scores such as the Alvarado score and the Pediatric Appendicitis Score, however, are variable.[69]

The Alvarado score is the most known scoring system. A score below 5 suggests against a diagnosis of appendicitis, whereas a score of 7 or more is predictive of acute appendicitis. In a person with an equivocal score of 5 or 6, a CT scan or ultrasound exam may be used to reduce the rate of negative appendectomy.

| Migratory right iliac fossa pain | 1 point |

| Anorexia | 1 point |

| Nausea and vomiting | 1 point |

| Right iliac fossa tenderness | 2 points |

| Rebound abdominal tenderness | 1 point |

| Fever | 1 point |

| High white blood cell count (leukocytosis) | 2 points |

| Shift to left (segmented neutrophils) | 1 point |

| Total score | 10 points |

|---|

Pathology

[edit]Even for clinically certain appendicitis, routine histopathology examination of appendectomy specimens is of value for identifying unsuspected pathologies requiring further postoperative management.[70] Notably, appendix cancer is found incidentally in about 1% of appendectomy specimens.[71]

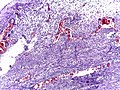

Pathology diagnosis of appendicitis can be made by detecting a neutrophilic infiltrate of the muscularis propria.

Periappendicitis (inflammation of tissues around the appendix) is often found in conjunction with other abdominal pathology.[72]

-

Micrograph of appendicitis and periappendicitis. H&E stain

-

Micrograph of appendicitis showing neutrophils in the muscularis propria. H&E stain

-

Acute suppurative appendicitis with perforation (at right). H&E stain

| Pattern | Gross pathology | Light microscopy | Image | Clinical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute intraluminal inflammation | None visible |

|

|

Probably none |

| Acuta mucosal inflammation | None visible |

|

May be secondary to enteritis. | |

| Suppurative acute appendicitis | May be inapparent.

|

|

|

Can be presumed to be primary cause of symptoms |

| Gangrenous/necrotizing appendicitis |

|

|

|

Will perforate if untreated |

| Periappendicitis | May be inapparent.

|

|

|

If isolated, probably secondary to other disease |

| Eosinophilic appendicitis | None visible |

|

Possibly parasitic, or eosinophilic enteritis. |

Differential diagnosis

[edit]

Children: Gastroenteritis, mesenteric adenitis, Meckel's diverticulitis, intussusception, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, lobar pneumonia, urinary tract infection (abdominal pain in the absence of other symptoms can occur in children with UTI), new-onset Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis, pancreatitis, and abdominal trauma from child abuse; distal intestinal obstruction syndrome in children with cystic fibrosis; typhlitis in children with leukemia.

Women: A pregnancy test is important for all women of childbearing age since an ectopic pregnancy can have signs and symptoms similar to those of appendicitis. Other obstetrical/ gynecological causes of similar abdominal pain in women include pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, menarche, dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, and Mittelschmerz (the passing of an egg in the ovaries approximately two weeks before menstruation).[74]

Men: testicular torsion

Adults: new-onset Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, regional enteritis, cholecystitis, renal colic, perforated peptic ulcer, pancreatitis, rectus sheath hematoma and epiploic appendagitis.

Elderly: diverticulitis, intestinal obstruction, colonic carcinoma, mesenteric ischemia, leaking aortic aneurysm.

The term "pseudoappendicitis" is used to describe a condition mimicking appendicitis.[75] It can be associated with Yersinia enterocolitica.[76]

Management

[edit]Acute appendicitis[77] is typically managed by surgery. While antibiotics are safe and effective for treating uncomplicated appendicitis,[16][7][78] 26% of people had a recurrence within a year and required an eventual appendectomy.[79] Antibiotics are less effective if an appendicolith is present.[80] Surgery is the standard management approach for acute appendicitis; however, the 2011 Cochrane review comparing appendectomy with antibiotics treatments has been withdrawn due to inclusion of a retracted article and not updated since.[81] While 51% of patients who were treated with antibiotics did not need an appendectomy three years after treatment,[82] the cost effectiveness of surgery versus antibiotics is unclear[83]

Using antibiotics to prevent potential postoperative complications in emergency appendectomy procedures is recommended, and the antibiotics are effective when given to a person before, during, or after surgery.[84]

Pain

[edit]Pain medications (such as morphine) do not appear to affect the accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of appendicitis and therefore should be given early in the patient's care.[85] Historically there were concerns among some general surgeons that analgesics would affect the clinical exam in children, and some recommended that they not be given until the surgeon was able to examine the person.[85]

Surgery

[edit]

The surgical procedure for the removal of the appendix is called an appendectomy. Appendectomy can be performed through open or laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic appendectomy has several advantages over open appendectomy as an intervention for acute appendicitis.[86]

Open appendectomy

[edit]For over a century, laparotomy (open appendectomy) was the standard treatment for acute appendicitis.[87] This procedure consists of the removal of the infected appendix through a single large incision in the lower right area of the abdomen.[88] The incision in a laparotomy is usually 2 to 3 inches (51 to 76 mm) long.

During an open appendectomy, the person with suspected appendicitis is placed under general anesthesia to keep the muscles completely relaxed and to keep the person unconscious. The incision is two to three inches (76 mm) long, and it is made in the right lower abdomen, several inches above the hip bone. Once the incision opens the abdomen cavity, and the appendix is identified, the surgeon removes the infected tissue and cuts the appendix from the surrounding tissue. After careful and close inspection of the infected area, and ensuring there are no signs that surrounding tissues are damaged or infected. In case of complicated appendicitis managed by an emergency open appendectomy, abdominal drainage (a temporary tube from the abdomen to the outside to avoid abscess formation) may be inserted, but this may increase the hospital stay.[89][needs update] The surgeon will start closing the incision. This means sewing the muscles and using surgical staples or stitches to close the skin up. To prevent infections, the incision is covered with a sterile bandage or surgical adhesive.

Laparoscopic appendectomy

[edit]Laparoscopic appendectomy was introduced in 1983 and has become an increasingly prevalent intervention for acute appendicitis.[90] This surgical procedure consists of making three to four incisions in the abdomen, each 0.25 to 0.5 inches (6.4 to 12.7 mm) long. This type of appendectomy is made by inserting a special surgical tool called a laparoscope into one of the incisions. The laparoscope is connected to a monitor outside the person's body, and it is designed to help the surgeon to inspect the infected area in the abdomen. The other two incisions are made for the specific removal of the appendix by using surgical instruments. Laparoscopic surgery requires general anesthesia, and it can last up to two hours. Laparoscopic appendectomy has several advantages over open appendectomy, including a shorter post-operative recovery, less post-operative pain, and lower superficial surgical site infection rate. However, the occurrence of an intra-abdominal abscess is almost three times more prevalent in laparoscopic appendectomy than open appendectomy.[91]

Laparoscopic-assisted transumbilical appendectomy

[edit]In pediatric patients, the high mobility of the cecum allows externalization of the appendix through the umbilicus, and the entire procedure can be performed with a single incision. Laparoscopic-assisted transumbilical appendectomy is a relatively recent technique but with long published series and very good surgical and aesthetic results.[92]

Pre-surgery

[edit]The treatment begins by keeping the person who will be having surgery from eating or drinking for a given period, usually overnight. An intravenous drip is used to hydrate the person who will be having surgery. Antibiotics given intravenously such as cefuroxime and metronidazole may be administered early to help kill bacteria and thus reduce the spread of infection in the abdomen and postoperative complications in the abdomen or wound. Equivocal cases may become more difficult to assess with antibiotic treatment and benefit from serial examinations. If the stomach is empty (no food in the past six hours), general anaesthesia is usually used. Otherwise, spinal anaesthesia may be used.

Once the decision to perform an appendectomy has been made, the preparation procedure takes approximately one to two hours. Meanwhile, the surgeon will explain the surgery procedure and will present the risks that must be considered when performing an appendectomy. (With all surgeries there are risks that must be evaluated before performing the procedures.) The risks are different depending on the state of the appendix. If the appendix has not ruptured, the complication rate is only about 3% but if the appendix has ruptured, the complication rate rises to almost 59%.[93] The most usual complications that can occur are pneumonia, hernia of the incision, thrombophlebitis, bleeding and adhesions. Evidence indicates that a delay in obtaining surgery after admission results in no measurable difference in outcomes to the person with appendicitis.[94][95]

The surgeon will explain how long the recovery process should take. Abdomen hair is usually removed to avoid complications that may appear regarding the incision.

In most cases, patients going in for surgery experience nausea or vomiting that require medication before surgery. Antibiotics, along with pain medication, may be administered before appendectomies.

After surgery

[edit]

Hospital lengths of stay typically range from a few hours to a few days but can be a few weeks if complications occur. The recovery process may vary depending on the severity of the condition: if the appendix had ruptured or not before surgery. Appendix surgery recovery is generally much faster if the appendix did not rupture.[96] It is important that people undergoing surgery respect their doctor's advice and limit their physical activity so the tissues can heal. Recovery after an appendectomy may not require diet changes or a lifestyle change.

The length of hospital stays for appendicitis varies on the severity of the condition. A study from the United States found that in 2010, the average appendicitis hospital stay was 1.8 days. For stays where the person's appendix had ruptured, the average length of stay was 5.2 days.[14]

After surgery, the patient will be transferred to a postanesthesia care unit, so their vital signs can be closely monitored to detect anesthesia- or surgery-related complications. Pain medication may be administered if necessary. After patients are completely awake, they are moved to a hospital room to recover. Most individuals will be offered clear liquids the day after the surgery, then progress to a regular diet when the intestines start to function correctly. Patients are recommended to sit upon the edge of the bed and walk short distances several times a day. Moving is mandatory, and pain medication may be given if necessary. Full recovery from appendectomies takes about four to six weeks but can be prolonged to up to eight weeks if the appendix had ruptured.

Prognosis

[edit]Most people with appendicitis recover quickly after surgical treatment, but complications can occur if treatment is delayed or if peritonitis occurs. Recovery time depends on age, condition, complications, and other circumstances, including the amount of alcohol consumption, but usually is between 10 and 28 days. For young children (around ten years old), the recovery takes three weeks.

The possibility of peritonitis is the reason why acute appendicitis warrants rapid evaluation and treatment. People with suspected appendicitis may have to undergo a medical evacuation. Appendectomies have occasionally been performed in emergency conditions (i.e., not in a proper hospital) when a timely medical evacuation was impossible.

Typical acute appendicitis responds quickly to appendectomy and occasionally will resolve spontaneously. If appendicitis resolves spontaneously, it remains controversial whether an elective interval appendectomy should be performed to prevent a recurrent episode of appendicitis. Atypical appendicitis (associated with suppurative appendicitis) is more challenging to diagnose and is more apt to be complicated even when operated early. In either condition, prompt diagnosis and appendectomy yield the best results with full recovery in two to four weeks usually. Mortality and severe complications are unusual but do occur, especially if peritonitis persists and is untreated.

Another entity known as the appendicular lump is talked about. It happens when the appendix is not removed early during infection, and omentum and intestine adhere to it, forming a palpable lump. During this period, surgery is risky unless there is pus formation evident by fever and toxicity or by ultrasound. Medical management treats the condition.

An unusual complication of an appendectomy is "stump appendicitis": inflammation occurs in the remnant appendiceal stump left after a prior incomplete appendectomy.[97] Stump appendicitis can occur months to years after initial appendectomy and can be identified with imaging modalities such as ultrasound.[98]

History

[edit]The history of appendicitis traces back to ancient medical texts, though its clear clinical understanding emerged in the 19th century. Berengario da Carpi provided the first recorded description of the appendix in the 16th century, followed by Andreas Vesalius and Gabriele Falloppio. Clinical understanding progressed in the 18th and 19th centuries, marked by Lorenz Heister's autopsy findings, Claudius Aymand's surgical intervention, and J. Mestivier's operation for appendicitis. The term "appendicitis" was coined by the American physician Reginald Heber Fitz in 1886, leading to standardized diagnosis and treatment, including Charles McBurney's identification of McBurney's point. Modern appendectomy techniques evolved in the early 20th century, coinciding with advancements in pathology, notably demonstrated by Ludwig Aschoff in 1908.[99][100]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Appendicitis is most common between the ages of 5 and 40.[102] In 2013, it resulted in 72,000 deaths globally, down from 88,000 in 1990.[103]

In the United States, there were nearly 293,000 hospitalizations involving appendicitis in 2010.[14] Appendicitis is one of the most frequent diagnoses for emergency department visits resulting in hospitalization among children ages 5–17 years in the United States.[104]

Adults presenting to the emergency department with a known family history of appendicitis are more likely to have this disease than those without.[105]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "appendicitis". Medical Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2013-12-30.

- ^ a b c d e Graffeo CS, Counselman FL (November 1996). "Appendicitis". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 14 (4): 653–671. doi:10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70273-x. PMID 8921763.

- ^ a b c d Hobler K (Spring 1998). "Acute and Suppurative Appendicitis: Disease Duration and its Implications for Quality Improvement" (PDF). Permanente Medical Journal. 2 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-03-06. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- ^ a b c d Paulson EK, Kalady MF, Pappas TN (January 2003). "Clinical practice. Suspected appendicitis" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (3): 236–242. doi:10.1056/nejmcp013351. PMID 12529465. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-22. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ^ Ferri FF (2010). Ferri's differential diagnosis: a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. pp. Chapter A. ISBN 978-0-323-07699-9.

- ^ a b c d e Longo DL, et al., eds. (2012). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. Chapter 300. ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Lobo DN (April 2012). "Safety and efficacy of antibiotics compared with appendicectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMJ. 344: e2156. doi:10.1136/bmj.e2156. PMC 3320713. PMID 22491789.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ a b Pieper R, Kager L, Tidefeldt U (1982). "Obstruction of appendix vermiformis causing acute appendicitis. An experimental study in the rabbit". Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica. 148 (1): 63–72. PMID 7136413.

- ^ Dölling M, Rahimli M, Pachmann J (2024). "Hidden Appendicoliths and Their Impact on the Severity and Treatment of Acute Appendicitis". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 13 (14): 4166. doi:10.3390/jcm13144166. PMC 11278186. PMID 39064205.

- ^ a b c Tintinalli JE, ed. (2011). Emergency medicine: a comprehensive study guide (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. Chapter 84. ISBN 978-0-07-174467-6. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Schwartz's principles of surgery (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. 2010. pp. Chapter 30. ISBN 978-0-07-154770-3.

- ^ a b c Barrett ML, Hines AL, Andrews RM (July 2013). "Trends in Rates of Perforated Appendix, 2001–2010" (PDF). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Brief #159. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PMID 24199256. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-20.

- ^ a b Shogilev DJ, Duus N, Odom SR, Shapiro NI (November 2014). "Diagnosing appendicitis: evidence-based review of the diagnostic approach in 2014". The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine (Review). 15 (7): 859–871. doi:10.5811/westjem.2014.9.21568. PMC 4251237. PMID 25493136.

- ^ a b Javanmard-Emamghissi H (2021). "Antibiotics as first-line alternative to appendicectomy in adult appendicitis: 90-day follow-up from a prospective, multicentre cohort study". The British Journal of Surgery. 108 (11): 1351–1359. doi:10.1093/bjs/znab287. PMC 8499866. PMID 34476484. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ "Appendicitis: Surgical vs. Medical Treatment | Science-Based Medicine". sciencebasedmedicine.org. 2020-11-24. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- ^ Mason RJ (August 2008). "Surgery for appendicitis: is it necessary?". Surgical Infections. 9 (4): 481–488. doi:10.1089/sur.2007.079. PMID 18687030.

- ^ Wangensteen OH, Bowers WF (1937). "Significance of the obstructive factor in the genesis of acute appendicitis". Archives of Surgery. 34 (3): 496–526. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1937.01190090121006.

- ^ Hollerman J, Bernstein MA, Kottamasu SR, Sirr SA (1988). "Acute recurrent appendicitis with appendicolith". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 6 (6): 614–617. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(88)90105-2. PMID 3052484.

- ^ a b Dehghan A, Moaddab AH, Mozafarpour S (June 2011). "An unusual localization of trichobezoar in the appendix". The Turkish Journal of Gastroenterology. 22 (3): 357–358. doi:10.4318/tjg.2011.0232. PMID 21805435.

- ^ Jones BA, Demetriades D, Segal I, Burkitt DP (July 1985). "The prevalence of appendiceal fecaliths in patients with and without appendicitis. A comparative study from Canada and South Africa". Annals of Surgery. 202 (1): 80–82. doi:10.1097/00000658-198507000-00013. PMC 1250841. PMID 2990360.

- ^ Nitecki S, Karmeli R, Sarr MG (September 1990). "Appendiceal calculi and fecaliths as indications for appendectomy". Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 171 (3): 185–188. PMID 2385810.

- ^ Arnbjörnsson E (1985). "Acute appendicitis related to faecal stasis". Annales Chirurgiae et Gynaecologiae. 74 (2): 90–93. PMID 2992354.

- ^ Raahave D, Christensen E, Moeller H, Kirkeby LT, Loud FB, Knudsen LL (February 2007). "Origin of acute appendicitis: fecal retention in colonic reservoirs: a case control study". Surgical Infections. 8 (1): 55–62. doi:10.1089/sur.2005.04250. PMID 17381397.

- ^ Burkitt DP (September 1971). "The aetiology of appendicitis". The British Journal of Surgery. 58 (9): 695–699. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800580916. PMC 1598350. PMID 4937032.

- ^ Segal I, Walker AR (1982). "Diverticular disease in urban Africans in South Africa". Digestion. 24 (1): 42–46. doi:10.1159/000198773. PMID 6813167.

- ^ Arnbjörnsson E (May 1982). "Acute appendicitis as a sign of a colorectal carcinoma". Journal of Surgical Oncology. 20 (1): 17–20. doi:10.1002/jso.2930200105. PMID 7078180. S2CID 30187238.

- ^ Burkitt DP, Walker AR, Painter NS (December 1972). "Effect of dietary fibre on stools and the transit-times, and its role in the causation of disease". Lancet. 2 (7792): 1408–1412. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(72)92974-1. PMID 4118696.

- ^ Adamidis D, Roma-Giannikou E, Karamolegou K, Tselalidou E, Constantopoulos A (May 2000). "Fiber intake and childhood appendicitis". International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 51 (3): 153–157. doi:10.1080/09637480050029647. PMID 10945110. S2CID 218989618.

- ^ Hugh TB, Hugh TJ (July 2001). "Appendicectomy – becoming a rare event?". The Medical Journal of Australia. 175 (1): 7–8. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143501.x. PMID 11476215. S2CID 33795090. Archived from the original on 2006-08-26.

- ^ Gear JS, Brodribb AJ, Ware A, Mann JI (January 1981). "Fibre and bowel transit times". The British Journal of Nutrition. 45 (1): 77–82. doi:10.1079/BJN19810078. PMID 6258626.

- ^ a b c National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). (n.d.). Appendicitis – Diagnosis. Retrieved September 21, 2023, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/appendicitis/diagnosis

- ^ a b c Echevarria S, Rauf F, Hussain N, Zaka H, Farwa UE, Ahsan N, Broomfield A, Akbar A, Khawaja UA (April 2023). "Typical and Atypical Presentations of Appendicitis and Their Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment: A Literature Review". Cureus. 15 (4): e37024. doi:10.7759/cureus.37024. PMC 10152406. PMID 37143626.

- ^ Oh JS, Kim KW, Cho HJ (September 2012). "Left-sided appendicitis in a patient with situs inversus totalis". Journal of the Korean Surgical Society. 83 (3): 175–178. doi:10.4174/jkss.2012.83.3.175. PMC 3433555. PMID 22977765.

- ^ Ashdown HF, D'Souza N, Karim D, Stevens RJ, Huang A, Harnden A (December 2012). "Pain over speed bumps in diagnosis of acute appendicitis: diagnostic accuracy study". BMJ. 345 (dec14 14): e8012. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8012. PMC 3524367. PMID 23247977.

- ^ Jones MW, Lopez RA, Deppen JG. Appendicitis. [Updated 2023 Apr 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493193/

- ^ a b c Sachdeva A, Dutta AK (2012). Advances in Pediatrics. JP Medical. p. 1432. ISBN 978-93-5025-777-7.

- ^ a b c Al-Salem AH (2020). Atlas of Pediatric Surgery: Principles and Treatment (1st ed.). Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-29210-2.

- ^ Virgilio Cd, Frank PN, Grigorian A (2015). Surgery. Springer. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-4939-1726-6.

- ^ a b Wolfson AB, Cloutier RL, Hendey GW, Ling LJ, Schaider JJ, Rosen CL (2014). Harwood-Nuss' Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. Wolters Kluwer Health. p. 5810. ISBN 978-1-4698-8948-1. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

Physical signs classically associated with acute appendicitis include Rovsing sign, psoas sign, and obturator sign.

- ^ Rovsing N (1907). "Indirektes Hervorrufen des typischen Schmerzes an McBurney's Punkt. Ein Beitrag zur diagnostik der Appendicitis und Typhlitis". Zentralblatt für Chirurgie (in German). 34. Leipzig: 1257–1259.

- ^ Dunster ES, Hunter JB, Sajous CE, Foster FP, Stragnell G, Klaunberg HJ, Martí-Ibáñez F (1922). International Record of Medicine and General Practice Clinics. New York Medical Journal. p. 663.

- ^ Emil Samuel Perman 1856–1946 "About the indications for surgery in appendicitis and an account of cases of Sabbatsberg Hospital in Hygiea 1904

- ^ a b c Gregory C (2010). "Appendicitis". CDEM Self Study Modules. Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine. Archived from the original on 2013-11-30.

- ^ Şahbaz NA, Bat O, Kaya B, Ulukent SC, İlkgül Ö, Özgün MY, Akça Ö (November 2014). "The clinical value of leucocyte count and neutrophil percentage in diagnosing uncomplicated (simple) appendicitis and predicting complicated appendicitis". Ulusal Travma ve Acil Cerrahi Dergisi = Turkish Journal of Trauma & Emergency Surgery. 20 (6): 423–426. doi:10.5505/tjtes.2014.75044. PMID 25541921.

- ^ Prasetya D, Rochadi, Gunadi (December 2019). "Accuracy of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio for diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children: A diagnostic study". Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 48: 35–38. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2019.10.013. PMC 6820073. PMID 31687137.

- ^ Shin DH, Cho YS, Cho GC, Ahn HC, Park SM, Lim SW, Oh YT, Cho JW, Park SO, Lee YH (2017). "Delta neutrophil index as an early predictor of acute appendicitis and acute complicated appendicitis in adults". World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 12: 32. doi:10.1186/s13017-017-0140-7. PMC 5525197. PMID 28747992.

- ^ Zhao, X., Yang, J. and Li, J. (2023) The predictive value of the C-reactive protein/albumin ratio in adult patients with complicated appendicitis. Journal of Laboratory Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1515/labmed-2023-0069

- ^ Bundy DG, Byerley JS, Liles EA, Perrin EM, Katznelson J, Rice HE (July 2007). "Does this child have appendicitis?". JAMA. 298 (4): 438–451. doi:10.1001/jama.298.4.438. PMC 2703737. PMID 17652298.

- ^ American College of Radiology, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American College of Radiology, archived (PDF) from the original on April 16, 2012, retrieved August 17, 2012

- ^ Krishnamoorthi R, Ramarajan N, Wang NE, Newman B, Rubesova E, Mueller CM, Barth RA (April 2011). "Effectiveness of a staged US and CT protocol for the diagnosis of pediatric appendicitis: reducing radiation exposure in the age of ALARA". Radiology. 259 (1): 231–239. doi:10.1148/radiol.10100984. PMID 21324843.

- ^ Wan MJ, Krahn M, Ungar WJ, Caku E, Sung L, Medina LS, Doria AS (February 2009). "Acute appendicitis in young children: cost-effectiveness of US versus CT in diagnosis – a Markov decision analytic model". Radiology. 250 (2): 378–386. doi:10.1148/radiol.2502080100. PMID 19098225.

- ^ Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ (October 2004). "Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents". Annals of Internal Medicine. 141 (7): 537–546. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00011. PMID 15466771. S2CID 46371675.

- ^ a b Reddan T, Corness J, Mengersen K, Harden F (March 2016). "Ultrasound of paediatric appendicitis and its secondary sonographic signs: providing a more meaningful finding". Journal of Medical Radiation Sciences. 63 (1): 59–66. doi:10.1002/jmrs.154. PMC 4775827. PMID 27087976.

- ^ Reddan T, Corness J, Mengersen K, Harden F (June 2016). "Sonographic diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children: a 3-year retrospective". Sonography. 3 (3): 87–94. doi:10.1002/sono.12068. S2CID 78306243.

- ^ Lee SH, Yun SJ (April 2019). "Diagnostic performance of emergency physician-performed point-of-care ultrasonography for acute appendicitis: A meta-analysis". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 37 (4): 696–705. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.07.025. PMID 30017693. S2CID 51677455.

- ^ a b "UOTW #45 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 25 April 2015. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017.

- ^ Rud B, Vejborg TS, Rappeport ED, Reitsma JB, Wille-Jørgensen P (19 November 2019). "Computed tomography for diagnosis of acute appendicitis in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009977.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6953397. PMID 31743429.

- ^ Kim Y, Kang G, Moon SB (November 2014). "Increasing utilization of abdominal CT in the Emergency Department of a secondary care center: does it produce better outcomes in caring for pediatric surgical patients?". Annals of Surgical Treatment and Research. 87 (5): 239–244. doi:10.4174/astr.2014.87.5.239. PMC 4217253. PMID 25368849.

- ^ Liu B, Ramalho M, AlObaidy M, Busireddy KK, Altun E, Kalubowila J, Semelka RC (August 2014). "Gastrointestinal imaging-practical magnetic resonance imaging approach". World Journal of Radiology. 6 (8): 544–566. doi:10.4329/wjr.v6.i8.544. PMC 4147436. PMID 25170393.

- ^ Garcia K, Hernanz-Schulman M, Bennett DL, Morrow SE, Yu C, Kan JH (February 2009). "Suspected appendicitis in children: diagnostic importance of normal abdominopelvic CT findings with nonvisualized appendix". Radiology. 250 (2): 531–537. doi:10.1148/radiol.2502080624. PMID 19188320.

- ^ a b Doria AS, Moineddin R, Kellenberger CJ, Epelman M, Beyene J, Schuh S, Babyn PS, Dick PT (October 2006). "US or CT for Diagnosis of Appendicitis in Children and Adults? A Meta-Analysis". Radiology. 241 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1148/radiol.2411050913. PMID 16928974.

- ^ D'Souza N, Hicks G, Beable R, Higginson A, Rud B (2021-12-14). Cochrane Colorectal Group (ed.). "Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for diagnosis of acute appendicitis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (12): CD012028. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012028.pub2. PMC 8670723. PMID 34905621.

- ^ Burke LM, Bashir MR, Miller FH, Siegelman ES, Brown M, Alobaidy M, Jaffe TA, Hussain SM, Palmer SL, Garon BL, Oto A, Reinhold C, Ascher SM, Demulder DK, Thomas S, Best S, Borer J, Zhao K, Pinel-Giroux F, De Oliveira I, Resende D, Semelka RC (November 2015). "Magnetic resonance imaging of acute appendicitis in pregnancy: a 5-year multi-institutional study". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 213 (5): 693.e1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.026. PMID 26215327.

- ^ Rao PM, Rhea JT, Rao JA, Conn AK (July 1999). "Plain abdominal radiography in clinically suspected appendicitis: diagnostic yield, resource use, and comparison with CT". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 17 (4): 325–328. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(99)90077-3. PMID 10452424.

- ^ Boleslawski E, Panis Y, Benoist S, Denet C, Mariani P, Valleur P (March 1999). "Plain abdominal radiography as a routine procedure for acute abdominal pain of the right lower quadrant: prospective evaluation". World Journal of Surgery. 23 (3): 262–264. doi:10.1007/pl00013181. PMID 9933697. S2CID 23733164.

- ^ a b APPENDICITIS from Townsend: Sabiston Textbook of Surgery on MD Consult Archived December 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kulik DM, Uleryk EM, Maguire JL (January 2013). "Does this child have appendicitis? A systematic review of clinical prediction rules for children with acute abdominal pain". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 66 (1): 95–104. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.004. PMID 23177898.

- ^ Abd Al-Fatah M (2017). "Importance of histopathological evaluation of appendectomy specimens". Al-Azhar Assiut Medical Journal. 15 (2): 97. doi:10.4103/AZMJ.AZMJ_19_17. ISSN 1687-1693. S2CID 202550141.

- ^ Lee WS, Choi ST, Lee JN, Kim KK, Park YH, Baek JH (2011). "A retrospective clinicopathological analysis of appendiceal tumors from 3,744 appendectomies: a single-institution study". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 26 (5): 617–621. doi:10.1007/s00384-010-1124-1. ISSN 0179-1958. PMID 21234578. S2CID 12566272.

- ^ Fink AS, Kosakowski CA, Hiatt JR, Cochran AJ (June 1990). "Periappendicitis is a significant clinical finding". American Journal of Surgery. 159 (6): 564–568. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(06)80067-X. PMID 2349982.

- ^ Carr NJ (2000). "The pathology of acute appendicitis". Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 4 (1): 46–58. doi:10.1016/S1092-9134(00)90011-X. ISSN 1092-9134. PMID 10684382.

- ^ "Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Symptoms; Diseases and Conditions". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2015-05-07. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ^ Cunha BA, Pherez FM, Durie N (July 2010). "Swine influenza (H1N1) and acute appendicitis". Heart & Lung. 39 (6): 544–546. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2010.04.004. PMID 20633930.

- ^ Zheng H, Sun Y, Lin S, Mao Z, Jiang B (August 2008). Yersinia enterocolitica infection in diarrheal patients. Vol. 27. pp. 741–752. doi:10.1007/s10096-008-0562-y. ISBN 978-0-9600805-6-4. PMID 18575909. S2CID 23127869.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "appendicitis". health n surgery. 15 June 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-10-25.

- ^ Sallinen V, Akl EA, You JJ, Agarwal A, Shoucair S, Vandvik PO, Agoritsas T, Heels-Ansdell D, Guyatt GH, Tikkinen KA (May 2016). "Meta-analysis of antibiotics versus appendicectomy for non-perforated acute appendicitis". The British Journal of Surgery. 103 (6): 656–667. doi:10.1002/bjs.10147. PMC 5069642. PMID 26990957.

- ^ Harnoss JC, Zelienka I, Probst P, Grummich K, Müller-Lantzsch C, Harnoss JM, Ulrich A, Büchler MW, Diener MK (May 2017). "Antibiotics Versus Surgical Therapy for Uncomplicated Appendicitis: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Controlled Trials (PROSPERO 2015: CRD42015016882)". Annals of Surgery. 265 (5): 889–900. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002039. PMID 27759621. S2CID 41805607.

- ^ Huang L, Yin Y, Yang L, Wang C, Li Y, Zhou Z (May 2017). "Comparison of Antibiotic Therapy and Appendectomy for Acute Uncomplicated Appendicitis in Children: A Meta-analysis". JAMA Pediatrics. 171 (5): 426–434. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0057. PMC 5470362. PMID 28346589.

- ^ Wilms IM, Suykerbuyk-de Hoog DE, de Visser DC, Janzing HM (1 October 2020). "Appendectomy versus antibiotic treatment for acute appendicitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (10): CD008359. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008359.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10631378. PMID 33001448. S2CID 222168573.

- ^ "Comparing Surgery versus Antibiotics for Treating Adults with Uncomplicated Appendicitis - Evidence Update for Clinicians | PCORI". www.pcori.org. 2024-05-06. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ^ Georgiou R, Eaton S, Stanton MP, Pierro A, Hall NJ (March 2017). "Efficacy and Safety of Nonoperative Treatment for Acute Appendicitis: A Meta-analysis" (PDF). Pediatrics. 139 (3): e20163003. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3003. PMID 28213607. S2CID 2292989.

- ^ Andersen BR, Kallehave FL, Andersen HK (July 2005). "Antibiotics versus placebo for prevention of postoperative infection after appendicectomy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (3): CD001439. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001439.pub2. PMC 8407323. PMID 16034862.

- ^ a b Anderson M, Collins E (November 2008). "Analgesia for children with acute abdominal pain and diagnostic accuracy". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 93 (11): 995–997. doi:10.1136/adc.2008.137174. PMID 18305071. S2CID 219246210. Archived from the original on 2013-05-17.

- ^ Jaschinski T, Mosch CG, Eikermann M, Neugebauer EA, Sauerland S (November 2018). "Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (11): CD001546. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001546.pub4. PMC 6517145. PMID 30484855.

- ^ Berry J, Malt RA (November 1984). "Appendicitis near its centenary". Annals of Surgery. 200 (5): 567–575. doi:10.1097/00000658-198411000-00002. PMC 1250537. PMID 6385879.

- ^ "Appendicitis". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 2010-02-01. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Li Z, Li Z, Zhao L, Cheng Y, Cheng N, Deng Y (August 2021). "Abdominal drainage to prevent intra-peritoneal abscess after appendectomy for complicated appendicitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (8): CD010168. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010168.pub4. PMC 8407456. PMID 34402522.

- ^ Semm K (March 1983). "Endoscopic appendectomy". Endoscopy. 15 (2): 59–64. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1021466. PMID 6221925. S2CID 45763958.

- ^ Siewert B, Raptopoulos V, Liu SI, Hodin RA, Davis RB, Rosen MP (November 2003). "CT predictors of failed laparoscopic appendectomy". Radiology. 229 (2): 415–420. doi:10.1148/radiol.2292020825. PMID 14595145.

- ^ Sekioka A, Takahashi T, Yamoto M, Miyake H, Fukumoto K, Nakaya K, Nomura A, Yamada Y, Urushihara N (December 2018). "Outcomes of Transumbilical Laparoscopic-Assisted Appendectomy and Conventional Laparoscopic Appendectomy for Acute Pediatric Appendicitis in a Single Institution". Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques. Part A. 28 (12): 1548–1552. doi:10.1089/lap.2018.0306. ISSN 1557-9034. PMID 30088968. S2CID 51941735.

- ^ "Appendicitis". Encyclopedia of Surgery. Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ "'Emergency' appendix surgery can wait: MDs". CBC News. 2010-09-21. Archived from the original on 2016-06-30.

- ^ Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Hall BL, Russell TR, Nathens AB (September 2010). "Effect of delay to operation on outcomes in adults with acute appendicitis". Archives of Surgery. 145 (9): 886–892. doi:10.1001/archsurg.2010.184. PMID 20855760.

Delay of appendectomy for acute appendicitis in adults does not appear to adversely affect 30-day outcomes.

- ^ Appendicitis surgery, removal and reco very Retrieved on 2010-02-01 Archived January 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Liang MK, Lo HG, Marks JL (February 2006). "Stump appendicitis: a comprehensive review of literature". The American Surgeon. 72 (2): 162–166. doi:10.1177/000313480607200214. PMID 16536249. S2CID 37041386.

- ^ Reddan T, Corness J, Powell J, Harden F, Mengersen K (2016). "Stumped? It could be stump appendicitis". Sonography. 4: 36–39. doi:10.1002/sono.12098.

- ^ Rondelli D (22 January 2017). "The early days in the history of appendectomy". Hektoen International.

- ^ Fitz RH (1886). "Perforating inflammation of the vermiform appendix with special reference to its early diagnosis and treatment". American Journal of the Medical Sciences (92): 321–346.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved Nov 11, 2009.

- ^ Ellis H (March 2012). "Acute appendicitis". British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 73 (3): C46–48. doi:10.12968/hmed.2012.73.sup3.C46. PMID 22411604.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ Wier LM, Yu H, Owens PL, Washington R (June 2013). Overview of Children in the Emergency Department, 2010. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Brief #157 (Report). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03.

- ^ Drescher M, Marcotte S, Grant R, Staff I (2012-12-01). "Family History is a Predictor for Appendicitis in Adults in the Emergency Department". Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 13 (6): 468–471. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.6.6679. PMC 3555584. PMID 23359540.

External links

[edit]- Appendicitis at Curlie

- CT of the abdomen showing acute appendicitis

- Appendicitis, history, diagnosis and treatment by Surgeons Net Education

- Appendicitis: Acute Abdomen and Surgical Gastroenterology from the Merck Manual Professional (content last modified September 2007)

- Appendicitis – Symptoms Causes and Treatment Archived 2021-02-27 at the Wayback Machine at Health N Surgery

![Ultrasound showing appendicitis and an appendicolith[58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e0/UOTW_45_-_Ultrasound_of_the_Week_3.jpg/120px-UOTW_45_-_Ultrasound_of_the_Week_3.jpg)

![A normal appendix without and with compression. Absence of compressibility indicates appendicitis.[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/Ultrasonography_of_a_normal_appendix_without_and_with_compression.jpg/120px-Ultrasonography_of_a_normal_appendix_without_and_with_compression.jpg)