Starobilsk agreement

| Preliminary Political and Military Agreement between the Soviet Government of Ukraine and the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine | |

|---|---|

Insurgent army troops reading the terms of the draft agreement | |

| Type | Political and military alliance |

| Context | White offensive into Northern Taurida |

| Signed | 6 October 1920 |

| Location | Starobilsk, Donetsk, Ukraine |

| Expiry | 26 November 1920 (de facto) |

| Signatories | |

| Languages | Russian, Ukrainian |

The Starobilsk agreement was a 1920 political and military alliance between the Makhnovshchina, an anarchist mass movement led by Nestor Makhno's Insurgent Army, and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, which the Bolsheviks had established as the legitimate government of Ukraine.

The agreement was reached following the resurgence of the White movement in Ukraine, which forced the warring Bolshevik and Makhnovist factions to put aside their differences and work together against their common enemy. Its political clauses extended a number of civil liberties to the previously repressed Ukrainian anarchist movement, while its military clauses subordinated the Insurgent Army to the high command of the Red Army.

The agreement was effective from October to November 1920. Following the Soviet victory over the Whites at the siege of Perekop, the Red Army attacked the Makhnovists, bringing an end to the agreement and igniting a conflict between the two factions that would last until the complete suppression of the Makhnovshchina in August 1921.

Background

[edit]The Ukrainian anarchists were a historic ally of the Bolsheviks, going back to their collaboration during the October Revolution and the early months of the Ukrainian Civil War.[1] Following the 1919 Soviet invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian anarchist insurgents led by Nestor Makhno integrated themselves into the Red Army, but eventually mutinied due to political and military disagreements.[2] After defeating the White movement at the battle of Peregonovka, the Makhnovist movement rapidly expanded its influence throughout southern Ukraine.[3] They were then attacked by the Red Army in January 1920 and fought to a stalemate over the subsequent months, while the White movement began to once again make territorial gains.[4]

Preliminary overtures

[edit]In June 1920, the secretariat of the Nabat approached the All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee to propose an armistice with the Insurgent Army, but the offer was rebuffed.[5] Not long after, a member of the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries from Oleksandrivsk offered to act as a mediator between the two factions, but he too was rejected by the insurgents' Military Revolutionary Council, which insisted on the Insurgent Army fighting the Whites as an independent force.[6] Throughout the summer, offers for a ceasefire were sent by the insurgents to the Bolshevik government, but these received no response and fighting between the two factions persisted.[7]

By August 1920, a series of defeats in the Polish–Soviet War had forced the Bolsheviks to begin peace negotiations, while Wrangel had himself launched a devastating offensive against the 13th Red Army positions in left-bank Ukraine, extending the White lines as far as Katerynoslav, Mariupol and the Don.[8] The Insurgent Army found itself trapped between the Red and White armies, facing attacks from both, which ignited an argument within the Makhnovist leadership over whether or not to form an alliance with the Red Army. Vasyl Kurylenko and Viktor Bilash came out in support of the proposal, while Dmitry Popov and Semen Karetnyk opposed it, and Nestor Makhno himself was undecided.[9] They resolved to call a general assembly for the Insurgent Army to itself decide,[10] with the result being a narrow majority in favor of an alliance.[11] While waiting for a response from the Bolsheviks,[12] clashes between the two factions continued into September.[13]

Agreement

[edit]On 29 September, the Ukrainian Soviet government finally agreed to a truce with the insurgents,[14] without amalgamating the two forces together, and even allowed for the release of anarchists from the Cheka's prisons.[15] The government appointed Andriy Ivanov to head the Bolshevik delegation, which was dispatched to Starobilsk to draw up a preliminary agreement.[16] The following day, the Military Revolutionary Council of the Insurgent Army submitted a ceasefire request to the Southern Front of the Red Army, offering their subordination to Bolshevik command and the recognition of the Ukrainian Soviet government, on the condition that they be allowed to retain their own internal structure. On 2 October, Mikhail Frunze ratified the pact, ordering an immediate end to hostilities with the Insurgent Army.[17]

Terms

[edit]

On 6 October, the provisional agreement was signed by Andri Ivanov, Semen Karetnyk, Dmitry Popov and Viktor Bilash, with the armistice between the two factions entering into force the following day.[18] They then arranged for the final draft of the political-military agreement to be drawn up in the Ukrainian Soviet capital of Kharkiv, where the insurgents would be represented by Dmitry Popov, Abram Budanov and Vasyl Kurylenko.[19]

According to the political agreement: all anarchist political prisoners were to be released and political repression against the anarchist movement ceased; anarchists were to be extended a number of civil liberties including freedom of speech, freedom of the press and freedom of association, excluding any anti-Soviet agitation; and anarchists were to be allowed to freely participate in elections to the Soviets and the upcoming Fifth All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets.[20] This was signed by the Bolshevik delegation, represented by Yakov Yakovlev, and the Insurgent delegation, represented by Dmitry Popov and Vasyl Kurylenko.[21]

According to the military agreement: the Insurgent Army was to subject itself to the Red Army's high command, while retaining its internal structure and autonomy; the Insurgent Army pledged not to accept any units or deserters from the Red Army into its ranks; the Insurgent Army was obliged to inform its followers of the agreement and request the cessation of all hostilities against the Soviet government; and the families of Insurgent Army combatants were to receive the same benefits as the families of Red Army soldiers.[22] This was signed by the commanders of the Red Army's Southern Front, represented by Mikhail Frunze, Béla Kun and Sergey Gusev, and the Insurgent delegation, represented by Dmitry Popov and Vasyl Kurylenko.[23]

Reactions

[edit]

On 9 October, Vladimir Lenin spoke in favour of the alliance, believing that the Makhnovists would not want to repeat their conflict with the Bolsheviks after experiencing Wrangel's occupation. On 10 October, Trotsky published an article in which he questioned the alliance, calling on the Makhnovists to oust any kulaks and bandits from its ranks, and to recognise the Soviet government.[24] On 13 October, Makhno reaffirmed in an editorial that the insurgent movement did not recognise the authority of the Ukrainian SSR and refused political collaboration with the Bolsheviks, considering the pact to be a wholly military endeavor.[25]

On 15 October, the final draft of the agreement was signed, although the insurgent delegates remained in Kharkiv to resolve the fourth clause of the political pact,[18] which had been disputed by the Bolshevik delegation.[26] This fourth clause would have extended full autonomy to the Makhnovshchina, allowing them to establish institutions of workers' self-management and self-government in south-eastern Ukraine, under a federative agreement with the Ukrainian SSR.[27] The Bolsheviks feared this would limit their access to the Ukrainian rail network and turn the Makhnovshchina into a "magnet for all dissidents and refugees from Bolshevik-held territory."[28] While the Ukrainian Bolsheviks themselves were amenable to the idea,[29] their delegates claimed that the clause needed approval from Moscow and quietly dropped the subject.[30]

The All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee initially prevented the publication of the agreement, as they wanted to ensure the movement of Makhnovist troops to the front first. But after the Makhnovists threatened to halt the implementation of the agreement until its publication,[31] an abridged version of the text was published, omitting the fourth political clause.[32] The Bolsheviks were particularly keen on publicising the military clause on the extension of welfare, as they believed it would incentivise the insurgents to uphold the agreement.[33]

Despite the earlier hostilities, the insurgents acceded to the Bolshevik overtures, justifying the pact as a necessity due to the fight against Wrangel.[34] The insurgents were also unaware of the peace negotiations in Riga, which had already enforced an armistice between the Polish and Soviet forces, and underestimated the Red Army's capacity on the Southern Front.[35] The insurgents still hoped to win over the populace and considered themselves strong enough to militarily resist the Red Army, once the time for it came.[36]

The outcomes of the pact were immediate, seeing the release of the insurgent commanders Petro Havrylenko and Oleksiy Chubenko,[37] as well as the leading anarchist intellectual Volin, from the prisons of the Cheka.[38] Wounded Makhnovists, including Makhno himself, were also treated by the Red Army's medical corps.[37] The Ukrainian government declared an official amnesty on 4 November, allowing the Nabat newspaper to resume publication and giving space for a planned anarchist congress to take place in Kharkiv towards the end of November.[28]

The pact had significantly treated the Makhnovists and Bolsheviks as equal partners, despite the former's concession of military subordination to the latter, with the insurgents hoping that success against the Whites would oblige the Bolsheviks to allow the implementation of soviet democracy and the extension of civil liberties in Ukraine.[39] The terms of the pact were so favorable to the insurgents that the Red Army high command began to worry whether their own troops would soon begin defecting to the Makhnovist ranks once again.[40]

Alliance against Wrangel

[edit]Northern Taurida Operation

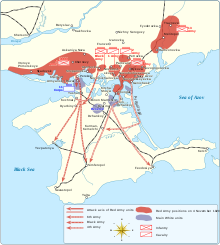

[edit]As relations once again started to soften between the Bolsheviks and Makhnovists, the insurgents were assigned their own theater, which included their home territory around Synelnykove, Oleksandrivsk, Huliaipole and Berdiansk.[41] As part of the 4th Army, the 10,000-strong insurgent detachment forced the Whites into a retreat on 11 October.[42] The Makhnovist advance was aided by a number of insurgents that were caught behind the White lines, some of whom had briefly formed an alliance with Wrangel during the Red Army offensive, who informed the Insurgent Army on the White positions.[43] After days of fighting, the insurgents routed the White "Drozdov Division" and recaptured Huliaipole, taking 4,000 prisoners of war in the process.[44] During this time, the 2nd Cavalry Army broke through the White lines at the Kakhivka bridgehead, opening space for an insurgent offensive towards Melitopol, in hopes of cutting off the White route of retreat.[45]

The Makhnovists requested three days of rest in Huliaipole but were ordered to continue their offensive, under threat of their alliance with the Red Army being nullified.[46] An insurgent expeditionary force, commanded by Semen Karetnyk with Petro Havrylenko as chief of staff, immediately set out from Huliaipole and captured Oleksandrivsk on 23 October.[47] Frunze ordered them to continued advancing, expecting them to reach isthmus of Perekop before the end of the month.[48] The Red forces themselves were advancing relatively slowly and failed to complete their planned encirclement of Wrangel's army. On 28 October, the Red Army finally reached the front against the Whites, with the 6th Army and 1st and 2nd Cavalry Armies taking the left flank along the Dnieper, while the 4th and 13th Armies took the right flank from Oleksandrivsk to the Azov Sea.[49]

The following day, Karetnyk's detachment went on to capture Tokmak, where they took 200 prisoners and seized 4 artillery cannons and machine-guns.[50] They then continued on through Melitopol all the way to the Syvash, forcing the Whites to retreat from mainland Ukraine to Crimea.[51]

The decisive end of the Northern Taurida Operation saw the Whites suffer heavy casualties and lose a substantial amount of their equipment, reducing them to a fraction of their former strength.[52] Within only two weeks, Karetnyk's insurgent detachment had beaten back the Whites, almost completely independently of the supporting Red Army infantry and entirely without the anticipation of the Bolshevik command.[53] Karetnyk's force had been composed of only 4,000 infantry, 1,000 cavalry, 250 machine guns and 12 artillery cannons.[54] In contrast, the Red Army had 188,771 soldiers at the front and the Whites had 44,000. Crucially, it was the Makhnovist capture of Melitopol, regarded as the White stronghold in the region, that had turned the tide against the White movement and forced them back to Crimea.[53]

Perekop–Chonhar Operation

[edit]

On 3 November, Frunze moved his headquarters to Melitopol, where he began to plan the final attack against the Whites in Crimea.[55] The insurgents once again requested a short period of rest and recuperation, but this too was denied by Mikhail Frunze, who again threatened nullification of the alliance. In order to keep the insurgents isolated from sympathetic elements of the Red Army, Karetnyk's detachment was transferred from the 13th Army to the 4th Army, before being transferred again to the 6th Army, then the 2nd Cavalry Army and then back to the 4th Army, all within the space of two weeks.[56]

Up against heavy fortifications and with their Azov flotilla indisposed,[57] the Red command concluded it would be necessary to force the Syvash, between Perekop and Chonhar, which had been made fordable by unusually strong winds.[58] On 5 November, while within the 6th Army, Karetnyk's detachment received orders to attack the White positions at Perekop,[59] in what Sergey Kamenev reported to be a suicide mission.[60] August Kork reported that Karetnyk quickly turned back from the offensive, as his units had not been able to ford the Syvash.[61] With this in mind, it was decided that Karetnyk's detachment, along with the 15th and 52nd Rifle Divisions, would begin their assault on the night of 7 November.[62] The 15th and 52nd Divisions made the crossing and captured the north of the Lithuanian Peninsula, but a change in wind prevented Karetnyk's detachment from crossing. When the 7th and 9th Cavalry Divisions were able to make the crossing at 03:00, Karetnyk's detachment was ordered by Frunze to follow them at 05:00.[63]

Under heavy machine-gun fire,[64] Karetnyk led the assault against Mikhail Fostikov's Kuban Cossacks, pushing them back over the Syvash.[65] Alexei Marchenko led the insurgent cavalry,[66] covered from behind by Foma Kozhyn's machine gun regiment, which suffered heavy casualties during the crossing.[67] At this time, Karetnyk's detachment consisted of only 1,000 infantry, 700 cavalry, 191 machine guns and 6 artillery cannons, while Perekop was manned by thousands of White infantry, with 750 machine guns, 180 artillery cannons, 48 tanks and a number of armored trains.[68]

Despite the losses, Karetnyk's attack had allowed the Soviet forces to establish a bridgehead at the Lithuanian Peninsula, which provided them with a decisive offensive position.[69] On 9 November, the White cavalry led by Ivan Barbovich attacked the left flank of the 15th Division, briefly forcing them back. Karetnyk's detachment responded with their own cavalry charge, which fanned out just before clashing with the Whites, leaving them open to machine-gun fire from the insurgents' tachanki. This forced the Kuban Cossacks to retreat and bought the 15th and 52nd Divisions time to strengthen their lines, allowing the safe passage of reinforcements from the 51st Rifle Division and Nikolai Krylenko's cavalry brigade.[70] On 11 November, the Soviet forces were finally able to break through the White defensive line at Yushun, forcing Wrangel to order the evacuation of the Crimea.[71] In their final defeat on the Southern Front, 100,000 White soldiers and 50,000 civilians fled aboard 126 ships,[72] leaving only a few White holdouts in Siberia remaining.[73]

Over the following days, the Soviet forces advanced down the railway lines, with the insurgents capturing Simferopol on 13 November.[74] As Sevastopol was finally captured on 15 November, the insurgents were assigned quarters at Bulğanaq and Cav Cürek.[75] The White forces that had remained in Crimea, taken in by Frunze's promise of amnesty, were massacred by the Cheka, at the order of Bela Kun. Estimates of the prisoners of war executed during this period range from 13,000 to over 50,000.[76]

Aftermath

[edit]After the battle was over, Karetnyk's detachment was posted at Saky, in a move made by Frunze to ensure the Makhnovists were both isolated and prevented from leaving Crimea, even having the detachment surrounding by the 52nd Division, 3rd Cavalry Corps and the 2nd Brigade of the Latvian Riflemen. In a report to Kamenev, Frunze noted that the Makhnovists had "acquitted themselves reasonably well", regretting that they had not sustained heavier losses.[77] Frunze subsequently issued an order that Karetnyk's detachment be transferred to the Caucasian Front,[78] but without sending a copy of the order to Karetnyk, and directed two armies to concentrate near Huliaipole.[79]

On the day that Sevastopol was captured, Karetnyk informed Makhno of their victory over telegram, to which the insurgent chief-of-staff Hryhory Vasylivsky responded by declaring the end of the Starobilsk agreement and predicting a Bolshevik attack within the week.[80] By 23 November, Frunze was already preparing to openly break with the insurgents, accusing them of insubordination and banditry.[81] On the night of 26 November, the Red Army launched a coordinated offensive against the Makhnovshchina: Karetnyk and the insurgent staff were ambushed and executed,[82] Huliaipole was surrounded and captured,[83] and the anarchists in Kharkiv were rounded up and arrested.[84]

The subsequent conflict between the Makhnovists and Bolsheviks lasted until August 1921, when the Makhnovshchina was decisively defeated by the Red Army and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was established as the sole authority in the country.[85]

References

[edit]- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 15–16; Malet 1982, pp. 6–7; Skirda 2004, p. 40.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 39–72; Malet 1982, pp. 29–45; Shubin 2010, pp. 169–179; Skirda 2004, pp. 77–123.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 73–90; Malet 1982, pp. 45–53; Peters 1970, pp. 69–84; Shubin 2010, pp. 179–182; Skirda 2004, pp. 124–161.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 91–107; Malet 1982, pp. 54–63; Skirda 2004, pp. 162–190.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 62.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 62; Skirda 2004, pp. 187–189.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 107; Footman 1961, pp. 294–295; Malet 1982, p. 62.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 106–107; Footman 1961, pp. 294–295; Skirda 2004, pp. 191–194.

- ^ Malet 1982, pp. 62–63; Skirda 2004, p. 194.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 194.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 63; Skirda 2004, p. 194.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Malet 1982, pp. 61–62; Skirda 2004, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 109–110; Malet 1982, p. 63; Skirda 2004, p. 195.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 109–110; Skirda 2004, p. 195.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 63.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 110; Malet 1982, p. 64; Skirda 2004, p. 196.

- ^ a b Malet 1982, p. 65.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 65; Skirda 2004, p. 196.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 111; Footman 1961, p. 295; Malet 1982, p. 65; Peters 1970, pp. 126–127; Skirda 2004, p. 196.

- ^ Peters 1970, p. 127; Skirda 2004, p. 196.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 110–111; Footman 1961, p. 295; Malet 1982, pp. 65–66; Peters 1970, pp. 127–128; Skirda 2004, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Peters 1970, p. 128; Skirda 2004, p. 197.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 112.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 111; Footman 1961, pp. 295–296; Malet 1982, p. 65.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 111; Footman 1961, pp. 295–296; Malet 1982, pp. 65–66; Skirda 2004, p. 197.

- ^ a b Malet 1982, p. 66.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 111.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 111; Footman 1961, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 110.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 110; Footman 1961, p. 296.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 66; Skirda 2004, p. 199.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 200.

- ^ a b Skirda 2004, p. 201.

- ^ Footman 1961, p. 296; Malet 1982, p. 66; Skirda 2004, p. 201.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 111–112; Skirda 2004, p. 201.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Malet 1982, pp. 66–67; Skirda 2004, p. 223.

- ^ Malet 1982, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 112–113; Malet 1982, pp. 66–67; Skirda 2004, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 67.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 225.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 67; Skirda 2004, p. 225.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 113.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 113; Skirda 2004, p. 225.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 113–114; Footman 1961, p. 297; Malet 1982, pp. 67–68; Skirda 2004, p. 225.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 225–226.

- ^ a b Skirda 2004, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 114; Skirda 2004, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Malet 1982, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 227.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 68.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 114; Malet 1982, p. 68.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 114; Skirda 2004, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 68; Skirda 2004, p. 228.

- ^ Malet 1982, pp. 68–69; Skirda 2004, p. 228.

- ^ Malet 1982, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 114–115; Malet 1982, p. 69; Skirda 2004, p. 228.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 228.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 69; Skirda 2004, p. 230.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 114–115; Malet 1982, p. 69; Skirda 2004, p. 230.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 228–230.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 114–115; Skirda 2004, p. 230.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 115; Malet 1982, p. 69.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 115; Skirda 2004, p. 231.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 231.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 115; Footman 1961, p. 297; Malet 1982, p. 69; Skirda 2004, p. 231.

- ^ Malet 1982, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 232.

- ^ Skirda 2004, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 117; Malet 1982, p. 70.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 70.

- ^ Footman 1961, p. 297; Malet 1982, p. 70; Skirda 2004, p. 238.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 117–118; Malet 1982, p. 70.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 118; Footman 1961, p. 298; Malet 1982, p. 71; Peters 1970, pp. 87–88; Shubin 2010, pp. 185–186; Skirda 2004, p. 240.

- ^ Footman 1961, pp. 298–299; Malet 1982, p. 72; Shubin 2010, p. 186; Skirda 2004, p. 239.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 118; Footman 1961, p. 298; Shubin 2010, p. 186; Skirda 2004, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 118–127; Malet 1982, pp. 72–80; Skirda 2004, p. 236-263.

Bibliography

[edit]- Darch, Colin (2020). Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917-1921. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 9781786805263. OCLC 1225942343.

- Footman, David (1961). "Makhno". Civil War in Russia. Praeger Publications in Russian History and World Communism. Vol. 114. New York: Praeger. pp. 245–302. LCCN 62-17560. OCLC 254495418.

- Malet, Michael (1982). Nestor Makhno in the Russian Civil War. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-25969-6. OCLC 8514426.

- Peters, Victor (1970). Nestor Makhno: The Life of an Anarchist. Winnipeg: Echo Books. OCLC 7925080.

- Shubin, Aleksandr (2010). "The Makhnovist Movement and the National Question in the Ukraine, 1917–1921". In Hirsch, Steven J.; van der Walt, Lucien (eds.). Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870–1940. Studies in Global Social History. Vol. 6. Leiden: Brill. pp. 147–191. ISBN 9789004188495. OCLC 868808983.

- Skirda, Alexandre (2004) [1982]. Nestor Makhno–Anarchy's Cossack: The Struggle for Free Soviets in the Ukraine 1917–1921. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Oakland: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-902593-68-5. OCLC 60602979.